Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, serving from 1953 to 1961. During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he was

Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe and achieved the

five-star rank

A five-star rank is the highest military rank in many countries.Oxford English Dictionary (OED), 2nd Edition, 1989. "five" ... "five-star adj., ... (b) U.S., applied to a general or admiral whose badge of rank includes five stars;" The rank is th ...

as

General of the Army. Eisenhower planned and supervised two of the most consequential military campaigns of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

:

Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

in the

North Africa campaign

The North African campaign of World War II took place in North Africa from 10 June 1940 to 13 May 1943, fought between the Allies and the Axis Powers. It included campaigns in the Libyan and Egyptian deserts (Western Desert campaign, Desert Wa ...

in 1942–1943 and the

invasion of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 ( D-Day) with the ...

in 1944.

Eisenhower was born in

Denison, Texas, and raised in

Abilene, Kansas

Abilene (pronounced ) is a city in and the county seat of Dickinson County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of the city was 6,460. It is home of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Libra ...

. His family had a strong religious background, and his mother became a

Jehovah's Witness. Eisenhower, however, belonged to no organized church until 1952. He graduated from

West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

in 1915 and later married

Mamie Doud, with whom he had two sons. During

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, he was denied a request to serve in Europe and instead commanded a unit that trained

tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engine; ...

crews. Between the wars he served in staff positions in the US and the Philippines, reaching the rank of

brigadier general shortly before the entry of the US into World War II in 1941. After further promotion Eisenhower oversaw the Allied invasions of North Africa and

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

before supervising the invasions of

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. After the war ended in Europe, he served as

military governor of the

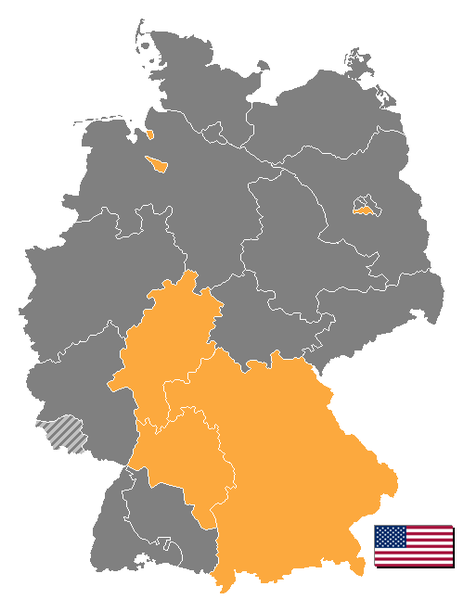

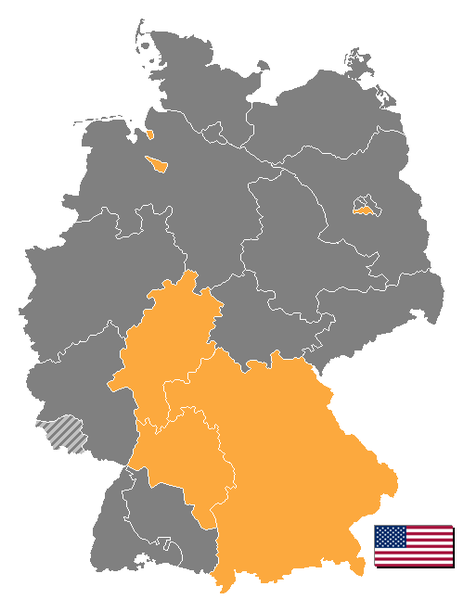

American-occupied zone of Germany (1945),

Army Chief of Staff (1945–1948),

president of Columbia University (1948–1953), and as the first

supreme commander of NATO (1951–1952).

In 1952, Eisenhower entered the presidential race as a

Republican to block the isolationist foreign policies of Senator

Robert A. Taft, who opposed

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

. Eisenhower won

that year's election and the

1956 election in

landslides, both times defeating

Adlai Stevenson II

Adlai Ewing Stevenson II (; February 5, 1900 – July 14, 1965) was an American politician and diplomat who was the United States ambassador to the United Nations from 1961 until his death in 1965. He previously served as the 31st governor of Ill ...

. Eisenhower's main goals in office were to

contain the spread of communism and reduce

federal deficits. In 1953, he considered using

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s to end the

Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

and may have threatened China with

nuclear attack if an armistice was not reached quickly. China did agree and

an armistice resulted, which remains in effect. His

New Look policy of nuclear deterrence prioritized "inexpensive" nuclear weapons while reducing funding for expensive Army divisions. He continued

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

's policy of recognizing

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

as the legitimate government of China, and he won congressional approval of the

Formosa Resolution. His administration provided aid to help the French try to fight Vietnamese Communists in the

First Indochina War

The First Indochina War (generally known as the Indochina War in France, and as the Anti-French Resistance War in Vietnam, and alternatively internationally as the French-Indochina War) was fought between French Fourth Republic, France and Việ ...

. After the French left, he gave strong financial support to the new state of

South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam (RVN; , VNCH), was a country in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975. It first garnered Diplomatic recognition, international recognition in 1949 as the State of Vietnam within the ...

.

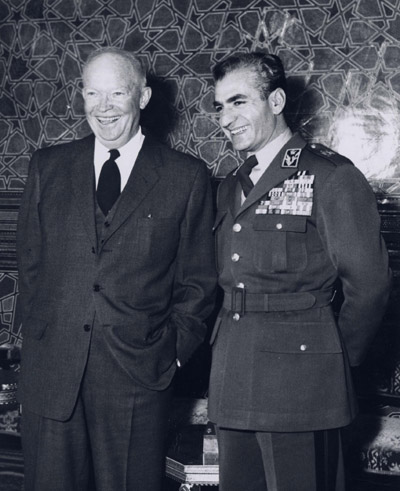

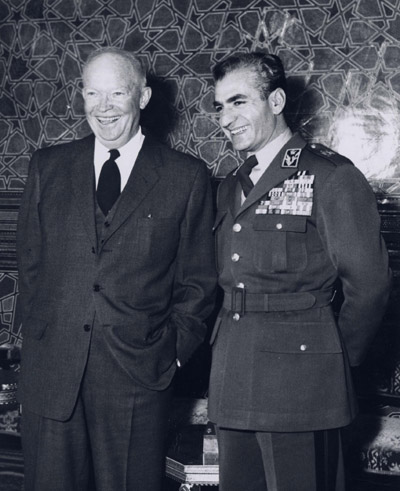

He supported

regime-changing military coups in

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

and

Guatemala

Guatemala, officially the Republic of Guatemala, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico, to the northeast by Belize, to the east by Honduras, and to the southeast by El Salvador. It is hydrologically b ...

orchestrated by his own administration. During the

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

of 1956, he condemned the Israeli, British, and French invasion of Egypt, and he forced them to withdraw. He also condemned the Soviet invasion during the

Hungarian Revolution of 1956

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 4 November 1956; ), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was an attempted countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the policies caused by ...

but took no action. He deployed 15,000 soldiers during the

1958 Lebanon crisis. Near the end of his term, a summit meeting with the Soviet leader

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

was cancelled when

a US spy plane was shot down over the Soviet Union. Eisenhower approved the

Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called or after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in April 1961 by the United States of America and the Cuban Democratic Revolutionary Front ...

, which was left to John F. Kennedy to carry out.

On the domestic front, Eisenhower governed as a

moderate conservative who continued

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

agencies and expanded

Social Security

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance ...

. He covertly opposed

Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

and contributed to the end of

McCarthyism

McCarthyism is a political practice defined by the political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals and a Fear mongering, campaign spreading fear of communist and Soviet influence on American institutions and of Soviet espionage i ...

by openly invoking

executive privilege

Executive privilege is the right of the president of the United States and other members of the executive branch to maintain confidential communications under certain circumstances within the executive branch and to resist some subpoenas and ot ...

. He signed the

Civil Rights Act of 1957

The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the first federal civil rights law passed by the United States Congress since the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The bill was passed by the 85th United States Congress and signed into law by President Dwight D. E ...

and sent Army troops to enforce federal court orders which

integrated schools in Little Rock, Arkansas. His administration undertook the development and construction of the

Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, or the Eisenhower Interstate System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Hi ...

, which remains the largest construction of roadways in American history. In 1957, following the Soviet launch of

Sputnik

Sputnik 1 (, , ''Satellite 1''), sometimes referred to as simply Sputnik, was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space progra ...

, Eisenhower led the American response which included the

creation of NASA and the establishment of a stronger, science-based education via the

National Defense Education Act. The Soviet Union began to reinforce

their own space program, escalating the

Space Race

The Space Race (, ) was a 20th-century competition between the Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between t ...

. His two terms saw

unprecedented economic prosperity except for a

minor recession in 1958. In

his farewell address, he expressed his concerns about the dangers of massive

military spending, particularly

deficit spending

Within the budgetary process, deficit spending is the amount by which spending exceeds revenue over a particular period of time, also called simply deficit, or budget deficit, the opposite of budget surplus. The term may be applied to the budg ...

and government contracts to private military manufacturers, which he dubbed "the

military–industrial complex

The expression military–industrial complex (MIC) describes the relationship between a country's military and the Arms industry, defense industry that supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy. A driving fac ...

". Historical evaluations of

his presidency place him among the

upper tier of US presidents.

Family background

The Eisenhauer (German for "iron hewer" or "iron miner") family migrated from the German village of

Karlsbrunn to the

Province of Pennsylvania

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn, who received the land through a grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania was derived from ...

in 1741.

Accounts vary as to how and when the German name Eisenhauer was

anglicized

Anglicisation or anglicization is a form of cultural assimilation whereby something non-English becomes assimilated into or influenced by the culture of England. It can be sociocultural, in which a non-English place adopts the English language ...

.

David Jacob Eisenhower, Eisenhower's father, was a college-educated engineer, despite his own father's urging to stay on the family farm. Eisenhower's mother,

Ida Elizabeth (Stover) Eisenhower, of predominantly German Protestant ancestry, moved to Kansas from Virginia. She married David on September 23, 1885, in

Lecompton, Kansas

Lecompton (pronounced ) is a city in Douglas County, Kansas, Douglas County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of the city was 588. Lecompton, located on the Kansas River, was the ''de jur ...

, on the campus of their alma mater,

Lane University.

David owned a general store in

Hope, Kansas, but the business failed due to economic conditions and the family became impoverished. The Eisenhowers lived in Texas from 1889 until 1892, and later returned to Kansas, with $24 () to their name. David worked as a railroad mechanic and then at a creamery.

By 1898, the parents made a decent living and provided a suitable home for their large family.

Early life and education

Eisenhower was born David Dwight Eisenhower in Denison, Texas, on October 14, 1890, the third of seven sons born to Ida and David. His mother soon reversed his two forenames after his birth to avoid the confusion of having two Davids in the family.

He was named Dwight after the evangelist

Dwight L. Moody

Dwight Lyman Moody (February 5, 1837 – December 22, 1899), also known as D. L. Moody, was an American evangelist and publisher connected with Keswickianism, who founded the Moody Church, Northfield School and Mount Hermon School in Mas ...

. All of the boys were nicknamed "Ike", such as "Big Ike" (

Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used masculine English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Edgar'' (composed of ''wikt:en:ead, ead'' "rich, prosperous" and ''Gar (spear), gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the Late Midd ...

) and "Little Ike" (Dwight); the nickname was intended as an abbreviation of their last name. By World War II, only Dwight was still called "Ike".

In 1892, the family moved to

Abilene, Kansas

Abilene (pronounced ) is a city in and the county seat of Dickinson County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of the city was 6,460. It is home of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Libra ...

, which Eisenhower considered his hometown. As a child, he was involved in an accident that cost his younger brother

Earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. In modern Britain, an earl is a member of the Peerages in the United Kingdom, peerage, ranking below a marquess and above a viscount. A feminine form of ''earl'' never developed; instead, ...

an eye, for which he was remorseful for the remainder of his life. Eisenhower developed a keen and enduring interest in exploring the outdoors. He learned about hunting and fishing, cooking, and card playing from a man named Bob Davis who camped on the

Smoky Hill River.

While his mother was against war, it was her collection of history books that first sparked Eisenhower's interest in military history; he became a voracious reader on the subject. Other favorite subjects early in his education were arithmetic and spelling.

Eisenhower's parents set aside specific times at breakfast and at dinner for daily family Bible reading. Chores were regularly assigned and rotated among all the children, and misbehavior was met with unequivocal discipline, usually from David. His mother, previously a member (with David) of the

River Brethren

The River Brethren are a group of historically related Anabaptist Christian denominations originating in 1770, during the Radical Pietist movement among German colonists in Pennsylvania. In the 17th century, Mennonite refugees from Switzerl ...

(

Brethren in Christ Church) sect of the

Mennonite

Mennonites are a group of Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian communities tracing their roots to the epoch of the Radical Reformation. The name ''Mennonites'' is derived from the cleric Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland, part of ...

s,

joined the

International Bible Students Association, later known as

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a Christian denomination that is an outgrowth of the Bible Student movement founded by Charles Taze Russell in the nineteenth century. The denomination is nontrinitarian, millenarian, and restorationist. Russell co-fou ...

. The Eisenhower home served as the local meeting hall from 1896 to 1915, though Dwight never joined. His later decision to attend West Point saddened his mother, who felt that warfare was "rather wicked", but she did not overrule his decision. Speaking of himself in 1948, Eisenhower said he was "one of the most deeply religious men I know" though unattached to any "sect or organization". He was baptized in the

Presbyterian Church

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Christianity, Reformed Protestantism, Protestant tradition named for its form of ecclesiastical polity, church government by representative assemblies of Presbyterian polity#Elder, elders, known as ...

in 1953.

["Faith Staked Down"](_blank)

, ''Time'', February 9, 1953.

Eisenhower attended

Abilene High School and graduated in 1909.

As a freshman, he injured his knee and developed a leg infection that extended into his groin, which his doctor diagnosed as life-threatening. The doctor insisted that the leg be amputated but Dwight refused to allow it, and surprisingly recovered, though he had to repeat his freshman year. He and brother

Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used masculine English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Edgar'' (composed of ''wikt:en:ead, ead'' "rich, prosperous" and ''Gar (spear), gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the Late Midd ...

both wanted to attend college, though they lacked the funds. They made a pact to take alternate years at college while the other worked to earn the tuitions.

Edgar took the first turn at school, and Dwight was employed as a night supervisor at the Belle Springs Creamery. When Edgar asked for a second year, Dwight consented. At that time a friend,

Edward "Swede" Hazlett, was applying to the

Naval Academy

A naval academy provides education for prospective naval officers.

List of naval academies

See also

* Military academy

{{Authority control

Naval academies,

Naval lists ...

and urged Dwight to apply, since no tuition was required. Eisenhower requested consideration for either Annapolis or West Point with his Senator,

Joseph L. Bristow. Though Eisenhower was among the winners of the entrance-exam competition, he was beyond the age limit for the Naval Academy.

He accepted an appointment to West Point in 1911.

At West Point, Eisenhower relished the emphasis on traditions and on sports, but was less enthusiastic about the hazing, though he willingly accepted it as a plebe. He was also a regular violator of the more detailed regulations and finished school with a less than stellar discipline rating. Academically, Eisenhower's best subject by far was English. Otherwise, his performance was average, though he thoroughly enjoyed the typical emphasis of engineering on science and mathematics.

In athletics, Eisenhower later said that "not making the baseball team at West Point was one of the greatest disappointments of my life, maybe my greatest".

He made the

varsity football team and was a starter at

halfback in 1912, when he tried to tackle the legendary

Jim Thorpe

James Francis Thorpe (; May 22 or 28, 1887March 28, 1953) was an American athlete who won Olympic gold medals and played professional American football, football, baseball, and basketball. A citizen of the Sac and Fox Nation, Thorpe was ...

of the

Carlisle Indians. Eisenhower suffered a torn knee while being tackled in the next game, which was the last he played; he reinjured his knee on horseback and in the boxing ring,

[Eisenhower, Dwight D. (1967). ''At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends'', Garden City, New York, Doubleday & Company, Inc.] so he turned to fencing and gymnastics.

Eisenhower later served as junior varsity football coach and cheerleader, which caught the attention of General

Frederick Funston

Frederick Funston (November 9, 1865 – February 19, 1917), also known as Fighting Fred Funston, was a General officer, general in the United States Army, best known for his roles in the Spanish–American War and the Philippine–American ...

.

He graduated from West Point in the middle of the class of 1915, which became known as "

the class the stars fell on", because 59 members eventually became

general officer

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

s. After graduation in 1915, Second Lieutenant Eisenhower requested an assignment in the Philippines, which was denied; because of the ongoing

Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution () was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its ...

, he was posted to

Fort Sam Houston

Fort Sam Houston is a United States Army, U.S. Army post in San Antonio, Texas.

"Fort Sam Houston, TX • About Fort Sam Houston" (overview), US Army, 2007, webpageSH-Army. Known colloquially as "Fort Sam", it is named for the first president o ...

in

San Antonio

San Antonio ( ; Spanish for " Saint Anthony") is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in Greater San Antonio. San Antonio is the third-largest metropolitan area in Texas and the 24th-largest metropolitan area in the ...

, Texas, under the command of General Funston. In 1916, while stationed at Fort Sam Houston, Funston convinced him to become the football coach for

Peacock Military Academy;

he later became the coach at St. Louis College, now

St. Mary's University, and was an honorary member of the Sigma Beta Chi fraternity there.

Personal life

While Eisenhower was stationed in Texas, he met Mamie Doud of

Boone, Iowa

Boone ( ) is a city in Des Moines Township, Boone County, Iowa, Des Moines Township, and county seat of Boone County, Iowa, United States.

It is the principal city of the Boone, Iowa Micropolitan Statistical Area, which encompasses all of Boone ...

. They were immediately taken with each other. He proposed to her on

Valentine's Day

Valentine's Day, also called Saint Valentine's Day or the Feast of Saint Valentine, is celebrated annually on February 14. It originated as a Christian feast day honoring a Christian martyrs, martyr named Saint Valentine, Valentine, and ...

in 1916. A November wedding date in

Denver

Denver ( ) is a List of municipalities in Colorado#Consolidated city and county, consolidated city and county, the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Colorado, most populous city of the U.S. state of ...

, Colorado, was moved up to July 1 due to the impending

American entry into World War I

The United States entered into World War I on 6 April 1917, more than two and a half years after the war began in Europe. Apart from an Anglophile element urging early support for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, British and an a ...

; Funston approved 10 days of leave for their wedding. The Eisenhowers moved many times during their first 35 years of marriage.

The Eisenhowers had two sons. In late 1917 while he was in charge of training at

Fort Oglethorpe in

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, his wife Mamie had their first son,

Doud Dwight "Icky" Eisenhower, who died of

scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'', a Group A streptococcus (GAS). It most commonly affects children between five and 15 years of age. The signs and symptoms include a sore ...

at the age of three. Eisenhower was mostly reluctant to discuss his death. Their second son,

John Eisenhower, was born in Denver. John served in the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

, retired as a brigadier general, became an author and served as

Ambassador to Belgium from 1969 to 1971. He married Barbara Jean Thompson and had four children:

David

David (; , "beloved one") was a king of ancient Israel and Judah and the third king of the United Monarchy, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament.

The Tel Dan stele, an Aramaic-inscribed stone erected by a king of Aram-Dam ...

, Barbara Ann,

Susan Elaine and

Mary Jean. David, after whom

Camp David

Camp David is a country retreat for the president of the United States. It lies in the wooded hills of Catoctin Mountain Park, in Frederick County, Maryland, near the towns of Thurmont, Maryland, Thurmont and Emmitsburg, Maryland, Emmitsburg, a ...

is named, married

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

's daughter

Julie in 1968.

Eisenhower was a golf enthusiast later in life, and he joined the

Augusta National Golf Club

Augusta National Golf Club, sometimes referred to as Augusta National, Augusta, or the National, is a golf club in Augusta, Georgia, United States. It is known for hosting the annual Masters Tournament.

Founded by Bobby Jones and Clifford Rob ...

in 1948. He played golf frequently during and after his presidency and was unreserved in his passion for the game, to the point of golfing during winter; he ordered his golf balls painted black so he could see them better against snow. He had a basic golf facility installed at Camp David, and he became close friends with the Augusta National Chairman

Clifford Roberts, inviting Roberts to stay at the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

on numerous occasions. Roberts, an investment broker, also handled the Eisenhower family's investments.

He began

oil painting

Oil painting is a painting method involving the procedure of painting with pigments combined with a drying oil as the Binder (material), binder. It has been the most common technique for artistic painting on canvas, wood panel, or oil on coppe ...

while at Columbia University, after watching

Thomas E. Stephens paint Mamie's portrait. Eisenhower painted about 260 oils during the last 20 years of his life. The images were mostly landscapes but also portraits of subjects such as Mamie, their grandchildren, Field Marshal

Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and the ...

,

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, and

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

.

Wendy Beckett

Wendy Mary Beckett (25 February 1930 – 26 December 2018), better known as Sister Wendy, was a British Catholic religious sister and art historian who became known internationally during the 1990s when she presented a series of BBC television ...

stated that Eisenhower's paintings, "simple and earnest", caused her to "wonder at the hidden depths of this reticent president". A conservative in both art and politics, Eisenhower in a 1962 speech denounced modern art as "a piece of canvas that looks like a broken-down

Tin Lizzie, loaded with paint, has been driven over it".

''

Angels in the Outfield'' was Eisenhower's favorite movie. His favorite reading material for relaxation were the Western novels of

Zane Grey.

With his excellent memory and ability to focus, Eisenhower was skilled at cards. He learned poker, which he called his "favorite indoor sport", in Abilene. Eisenhower recorded West Point classmates' poker losses for payment after graduation and later stopped playing because his opponents resented having to pay him. A friend reported that after learning to play

contract bridge

Contract bridge, or simply bridge, is a trick-taking game, trick-taking card game using a standard 52-card deck. In its basic format, it is played by four players in two Team game, competing partnerships, with partners sitting opposite each othe ...

at West Point, Eisenhower played the game six nights a week for five months.

Eisenhower continued to play bridge throughout his military career. While stationed in the Philippines, he played regularly with President

Manuel Quezon

Manuel Luis Quezon y Molina (, , , ; 19 August 1878 – 1 August 1944), also known by his initials MLQ, was a Filipino lawyer, statesman, soldier, and politician who was president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines from 1935 until his d ...

, earning him the nickname the "Bridge Wizard of Manila".

An unwritten qualification for an officer's appointment to Eisenhower's staff during World War II was the ability to play bridge. He played even during the stressful weeks leading up to the D-Day landings. His favorite partner was General

Alfred Gruenther, considered the best player in the US Army; he appointed Gruenther his second-in-command at NATO partly because of his skill at bridge. Saturday night bridge games at the White House were a feature of his presidency. He was a strong player, though not an expert by modern standards. The great bridge player and popularizer

Ely Culbertson described his game as classic and sound with "flashes of brilliance" and said that "you can always judge a man's character by the way he plays cards. Eisenhower is a calm and collected player and never whines at his losses. He is brilliant in victory but never commits the bridge player's worst crime of gloating when he wins." Bridge expert

Oswald Jacoby frequently participated in the White House games and said, "The President plays better bridge than golf. He tries to break 90 at golf. At bridge, you would say he plays in the 70s."

World War I (1914–1918)

Eisenhower served initially in logistics and then the

infantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

at various camps in Texas and

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

until 1918. When the US entered

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, he immediately requested an overseas assignment but was denied and assigned to

Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas. In February 1918, he was transferred to

Camp Meade in

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

with the

65th Engineers. His unit was later ordered to France, but, to his chagrin, he received orders for the new

tank corps, where he was promoted to

brevet lieutenant colonel in the

National Army. He commanded a unit that trained tank crews at

Camp Colt – his first command. Though Eisenhower and his tank crews never saw combat, he displayed excellent organizational skills as well as an ability to accurately assess junior officers' strengths and make optimal placements of personnel.

His spirits were raised when the unit under his command received orders overseas to France. This time his wishes were thwarted when the

armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

was signed a week before his departure date. Completely missing out on the warfront left him depressed and bitter for a time, despite receiving the

Distinguished Service Medal for his work at home. In World War II, rivals who had combat service in the Great War (led by Gen.

Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and the ...

) sought to denigrate Eisenhower for his previous lack of combat duty, despite his stateside experience establishing a camp for thousands of troops and developing a full combat training schedule.

Between the Wars (1918–1939)

In service of generals

After the war, Eisenhower reverted to his regular rank of

captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

and a few days later was promoted to

major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

, a rank he held for 16 years.

The major was assigned in 1919 to a

transcontinental Army convoy to test vehicles and dramatize the need for improved roads. Indeed, the convoy averaged only from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco; later the improvement of highways became a signature issue for Eisenhower as president.

He assumed duties again at

Camp Meade, Maryland, commanding a battalion of tanks, where he remained until 1922. His schooling continued, focused on the nature of the next war and the role of the tank. His new expertise in

tank warfare was strengthened by a close collaboration with

George S. Patton,

Sereno E. Brett, and other senior tank leaders. Their leading-edge ideas of speed-oriented offensive tank warfare were strongly discouraged by superiors, who considered the new approach too radical and preferred to continue using tanks in a strictly supportive role for the infantry. Eisenhower was even threatened with

court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

for continued publication of these proposed methods of tank deployment, and he relented.

From 1920, Eisenhower served under a succession of talented generals –

Fox Conner,

John J. Pershing,

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

and

George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under pres ...

. He first became executive officer to General Conner in the

Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone (), also known as just the Canal Zone, was a International zone#Concessions, concession of the United States located in the Isthmus of Panama that existed from 1903 to 1979. It consisted of the Panama Canal and an area gene ...

, where, joined by Mamie, he served until 1924. Under Conner's tutelage, he studied military history and theory (including

Carl von Clausewitz

Carl Philipp Gottlieb von Clausewitz ( , ; born Carl Philipp Gottlieb Clauswitz; 1 July 1780 – 16 November 1831) was a Kingdom of Prussia, Prussian general and Military theory, military theorist who stressed the "moral" (in modern terms meani ...

's ''

On War

''Vom Kriege'' () is a book on war and military strategy by Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831), written mostly after the Napoleonic wars, between 1816 and 1830, and published posthumously by his wife Marie von Brühl in 1832. It ...

''), and later cited Conner's enormous influence on his military thinking, saying in 1962 that "Fox Conner was the ablest man I ever knew." Conner's comment on Eisenhower was, "

eis one of the most capable, efficient and loyal officers I have ever met." On Conner's recommendation, in 1925–1926 he attended the

Command and General Staff College

The United States Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC or, obsolete, USACGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is a graduate school for United States Army and sister service officers, interagency representatives, and international military ...

at

Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

, Kansas, where he graduated first in a class of 245 officers.

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Eisenhower's career stalled somewhat, as military priorities diminished; many of his friends resigned for high-paying business jobs. He was assigned to the

American Battle Monuments Commission

The American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) is an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the United States government that administers, operates, and maintains permanent U.S. military cemeteries, memoria ...

directed by General Pershing, and with the help of his brother

Milton Eisenhower, then a journalist at the

Agriculture Department, he produced a guide to American battlefields in Europe. He then was assigned to the

Army War College and graduated in 1928. After a one-year assignment in France, Eisenhower served as executive officer to General

George V. Moseley,

Assistant Secretary of War, from 1929 to February 1933. Major Eisenhower graduated from the

Army Industrial College in 1933 and later served on the faculty (it was later expanded to become the Industrial College of the Armed Services and is now known as the Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy).

His primary duty was planning for the next war, which proved most difficult in the midst of the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

. He then was posted as chief military aide to General Douglas MacArthur, Army Chief of Staff. In 1932, he participated in the clearing of the

Bonus March encampment in Washington, D.C. Although he was against the actions taken against the veterans and strongly advised MacArthur against taking a public role in it, he later wrote the Army's official incident report, endorsing MacArthur's conduct.

Philippine tenure (1935–1939)

In 1935, Eisenhower accompanied MacArthur to the Philippines, where he served as assistant military adviser to the

Philippine government

The government of the Philippines () has three interdependent branches: the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. The Philippines is governed as a unitary state under a presidential representative and democratic constitutional repub ...

in developing their army. MacArthur allowed Eisenhower to handpick an officer whom he thought would contribute to the mission. Hence he chose

James Ord, a classmate of his at West Point. Having been brought up in Mexico, which inculcated into him the Spanish culture which influenced both Mexico and the Philippines, Ord was deemed the right pick for the job. Eisenhower had strong philosophical disagreements with MacArthur regarding the role of the

Philippine Army

The Philippine Army (PA) () is the main, oldest and largest branch of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), responsible for ground warfare. , it had an estimated strength of 143,100 soldiers The service branch was established on December ...

and the leadership qualities that an American army officer should exhibit and develop in his subordinates. The antipathy between Eisenhower and MacArthur lasted the rest of their lives.

Historians have concluded that this assignment provided valuable preparation for handling the challenging personalities of

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, George S. Patton, George Marshall, and Bernard Montgomery during World War II. Eisenhower later emphasized that too much had been made of the disagreements with MacArthur and that a positive relationship endured. While in Manila, Mamie suffered a life-threatening stomach ailment but recovered fully. Eisenhower was promoted to the rank of permanent lieutenant colonel in 1936. He also learned to fly with the

Philippine Army Air Corps at the Zablan Airfield in

Camp Murphy under Capt.

Jesus Villamor, making a solo flight over the Philippines in 1937, and obtained his private pilot's license in 1939 at

Fort Lewis.

Also around this time, he was offered a post by the

Philippine Commonwealth Government, namely by then Philippine President

Manuel L. Quezon

Manuel Luis Quezon y Molina (, , , ; 19 August 1878 – 1 August 1944), also known by his initials MLQ, was a Filipino people, Filipino lawyer, statesman, soldier, and politician who was president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines from 1 ...

on recommendations by MacArthur, to become the chief of police of a new capital being planned, now named

Quezon City

Quezon City (, ; ), also known as the City of Quezon and Q.C. (read and pronounced in Filipino language, Filipino as Kyusi), is the richest and List of cities in the Philippines, most populous city in the Philippines. According to the 2020 c ...

, but he declined the offer.

World War II (1939–1945)

Eisenhower returned to the United States in December 1939 and was assigned as

commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or commander, or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually give ...

of the 1st Battalion,

15th Infantry Regiment at

Fort Lewis, Washington, later becoming the regimental executive officer. In March 1941 he was promoted to colonel and assigned as chief of staff of the newly activated

IX Corps under Major General

Kenyon Joyce. In June 1941, he was appointed chief of staff to General

Walter Krueger

Walter Krueger (26 January 1881 – 20 August 1967) was an American soldier and general officer in the first half of the 20th century. He commanded the Sixth United States Army in the South West Pacific Area during World War II. He rose fro ...

, Commander of the

Third Army, at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. After successfully participating in the

Louisiana Maneuvers, he was promoted to brigadier general on October 3, 1941.

After the

Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. At the tim ...

, Eisenhower was assigned to the General Staff in

Washington, where he served until June 1942 with responsibility for creating the major war plans to defeat Japan and Germany. He was appointed Deputy Chief in charge of Pacific Defenses under the Chief of War Plans Division (WPD), General

Leonard T. Gerow, and then succeeded Gerow as Chief of the War Plans Division. Next, he was appointed Assistant Chief of Staff in charge of the new Operations Division (which replaced WPD) under Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, who spotted talent and promoted accordingly.

At the end of May 1942, Eisenhower accompanied Lt. Gen.

Henry H. Arnold, commanding general of the

Army Air Forces, to London to assess the effectiveness of the theater commander in England, Maj. Gen.

James E. Chaney. He returned to Washington on June 3 with a pessimistic assessment, stating he had an "uneasy feeling" about Chaney and his staff. On June 23, 1942, he returned to London as Commanding General,

European Theater of Operations

The European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA) was a Theater (warfare), theater of Operations responsible for directing United States Army operations throughout the European theatre of World War II, from 1942 to 1945. It command ...

(ETOUSA), based in London and with a house in

Coombe, Kingston upon Thames

Coombe is a historic neighbourhood in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames in south west London, England. It sits on high ground, east of Norbiton. Most of the area was part of the former Municipal Borough of Malden and Coombe before local ...

, and took over command of ETOUSA from Chaney.

He was promoted to lieutenant general on July 7.

Operations Torch and Avalanche

In November 1942, Eisenhower was also appointed

Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force of the

North African Theater of Operations (NATOUSA) through the new operational Headquarters

Allied (Expeditionary) Force Headquarters (A(E)FHQ). The word "expeditionary" was dropped soon after his appointment for security reasons. The campaign in North Africa was designated Operation Torch and was planned

in the underground headquarters within the

Rock of Gibraltar

The Rock of Gibraltar (from the Arabic name Jabal Ṭāriq , meaning "Mountain of Tariq ibn Ziyad, Tariq") is a monolithic limestone mountain high dominating the western entrance to the Mediterranean Sea. It is situated near the end of a nar ...

. Eisenhower was the first non-British person to command

Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

in 200 years.

was deemed necessary to the campaign and Eisenhower encountered a "preposterous situation" with the multiple rival factions in France. His primary objective was to move forces successfully into

Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

and intending to facilitate that objective, he gave his support to

François Darlan as High Commissioner in North Africa, despite Darlan's previous high offices in

Vichy France

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the Battle of France, ...

and his continued role as commander-in-chief of the

French armed forces

The French Armed Forces (, ) are the military forces of France. They consist of four military branches – the Army, the Navy, the Air and Space Force, and the National Gendarmerie. The National Guard serves as the French Armed Forces' milita ...

. The

Allied leaders were "thunderstruck" by this from a political standpoint, though none had offered Eisenhower guidance with the problem in planning the operation. Eisenhower was severely criticized for the move. Darlan was assassinated on December 24 by

Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle, a French antifascist monarchist. Eisenhower later appointed as High Commissioner General

Henri Giraud, who had been installed by the Allies as Darlan's commander-in-chief.

Operation Torch also served as a valuable training ground for Eisenhower's combat command skills; during the initial phase of ''

Generalfeldmarschall

''Generalfeldmarschall'' (; from Old High German ''marahscalc'', "marshal, stable master, groom"; ; often abbreviated to ''Feldmarschall'') was a rank in the armies of several German states and the Holy Roman Empire, (''Reichsgeneralfeldmarsch ...

''

Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel (; 15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944), popularly known as The Desert Fox (, ), was a German '' Generalfeldmarschall'' (field marshal) during World War II. He served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of ...

's move into the

Kasserine Pass, Eisenhower created some confusion in the ranks by interference with the execution of battle plans by his subordinates. He also was initially indecisive in his removal of

Lloyd Fredendall, commanding

II Corps. He became more adroit in such matters in later campaigns. In February 1943, his authority was extended as commander of

AFHQ across the

Mediterranean basin to include the

British Eighth Army

The Eighth Army was a field army of the British Army during the Second World War. It was formed as the Western Army on 10 September 1941, in Egypt, before being renamed the Army of the Nile and then the Eighth Army on 26 September. It was cr ...

, commanded by

General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Sir Bernard Montgomery. The Eighth Army had

advanced across the Western Desert from the east and was ready for the start of the

Tunisia Campaign.

After the capitulation of

Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

forces in North Africa, Eisenhower oversaw the

invasion of Sicily. Once

Mussolini, the

Italian leader, had fallen in Italy, the Allies switched their attention to the mainland with

Operation Avalanche. But while Eisenhower argued with President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Churchill, who both insisted on unconditional surrender in exchange for helping the Italians, the Germans pursued an aggressive buildup of forces in the country. The Germans made the already tough battle more difficult by adding 19

divisions

Division may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

* Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting of 10,000 t ...

and initially outnumbering the

Allied forces 2 to 1.

Supreme Allied commander and Operation Overlord

In December 1943, President Roosevelt decided that Eisenhower – not Marshall – would be Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. The following month, he resumed command of

ETOUSA and the following month was officially designated as the

Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), serving in a dual role until the end of hostilities in Europe in May 1945. He was charged in these positions with planning and carrying out the Allied

assault on the coast of Normandy in June 1944 under the code name Operation Overlord, the liberation of Western Europe and the invasion of Germany.

Eisenhower, as well as the officers and troops under him, had learned valuable lessons in their previous operations, and their skills had all strengthened in preparation for the next most difficult campaign against the Germans—a beach landing assault. His first struggles, however, were with Allied leaders and officers on matters vital to the success of the Normandy invasion; he argued with Roosevelt over an essential agreement with

De Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

to use

French resistance

The French Resistance ( ) was a collection of groups that fought the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation and the Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy#France, collaborationist Vic ...

forces in covert operations against the Germans in advance of Operation Overlord. Admiral

Ernest J. King fought with Eisenhower over King's refusal to provide additional landing craft from the Pacific. Eisenhower also insisted that the British give him exclusive command over all strategic

air forces to facilitate Overlord, to the point of threatening to resign unless Churchill relented, which he did. Eisenhower then designed a bombing plan in France in advance of Overlord and argued with Churchill over the latter's concern with civilian casualties; de Gaulle interjected that the casualties were justified, and Eisenhower prevailed. He also had to skillfully manage to retain the services of the often unruly George S. Patton, by severely reprimanding him when Patton earlier had

slapped a subordinate, and then when Patton gave a speech in which he made improper comments about postwar policy.

The D-Day Normandy landings on June 6, 1944, were costly but successful. Two months later (August 15), the

invasion of Southern France took place, and control of forces in the southern invasion passed from the AFHQ to the SHAEF. Many thought that victory in Europe would come by summer's end, but the Germans did not capitulate for almost a year. From then until the

end of the war in Europe on May 8, 1945, Eisenhower, through SHAEF, commanded all Allied forces, and through his command of ETOUSA had administrative command of all US forces on the

Western Front north of the

Alps

The Alps () are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

...

. He was ever mindful of the inevitable loss of life and suffering that would be experienced by the troops under his command and their families. This prompted him to make a point of visiting every division involved in the invasion. Eisenhower's sense of responsibility was underscored by his draft of a statement to be issued if the invasion failed. It has been called one of the great speeches of history:

Liberation of France and victory in Europe

Once the coastal assault had succeeded, Eisenhower insisted on retaining personal control over the land battle strategy and was immersed in the command and supply of multiple assaults through France on Germany. Field Marshal Montgomery insisted priority be given to his

21st Army Group's attack being made in the north, while Generals

Bradley (

12th US Army Group) and

Devers (

Sixth US Army Group) insisted they be given priority in the center and south of the front (respectively). Eisenhower worked tirelessly to address the demands of the rival commanders to optimize Allied forces, often by giving them tactical latitude; many historians conclude this delayed the Allied victory in Europe. However, due to Eisenhower's persistence, the pivotal supply port at

Antwerp

Antwerp (; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of Antwerp Province, and the third-largest city in Belgium by area at , after ...

was successfully, albeit belatedly,

opened in late 1944.

In recognition of his senior position in the Allied command, on December 20, 1944, he was promoted to

General of the Army, equivalent to the rank of

Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

in most European armies. In this and the previous high commands he held, Eisenhower showed his great talents for leadership and diplomacy. Although he had never seen action himself, he won the respect of front-line commanders. He interacted adeptly with allies such as

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery and General

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

. He had serious disagreements with Churchill and Montgomery over questions of strategy, but these rarely upset his relationships with them. He dealt with Soviet

Marshal Zhukov, his Russian counterpart, and they became good friends.

In December 1944, the Germans launched a surprise counteroffensive, the

Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive or Unternehmen Die Wacht am Rhein, Wacht am Rhein, was the last major German Offensive (military), offensive Military campaign, campaign on the Western Front (World War II), Western ...

, which the Allies successfully repelled in early 1945 after Eisenhower repositioned his armies and improved weather allowed the

Army Air Force to engage. German defenses continued to deteriorate on both the

Eastern Front with the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

and the

Western Front with the Western Allies. The British wanted to capture Berlin, but Eisenhower decided it would be a military mistake for him to attack Berlin and said orders to that effect would have to be explicit. The British backed down but then wanted Eisenhower to move into

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

for political reasons. Washington refused to support Churchill's plan to use Eisenhower's army for political maneuvers against

Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

. The actual division of Germany followed the lines that Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin had previously agreed upon. The Soviet Red Army captured Berlin in a

very bloody large-scale battle, and the Germans finally surrendered on May 7, 1945.

Throughout 1945, the allied armies liberated numerous

Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps (), including subcamp (SS), subcamps on its own territory and in parts of German-occupied Europe.

The first camps were established in March 1933 immediately af ...

throughout Europe. As the allies learned the full extent of

the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

, Eisenhower anticipated that, in the future, attempts to recharacterize

Nazi crimes as propaganda (

Holocaust denial

Historical negationism, Denial of the Holocaust is an antisemitic conspiracy theory that asserts that the genocide of Jews by the Nazi Party, Nazis is a fabrication or exaggeration. It includes making one or more of the following false claims:

...

) would be made, and took steps against it by demanding extensive photo and film documentation of Nazi

extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe, primarily in occupied Poland, during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocau ...

s.

After World War II (1945–1953)

Military Governor of the American-occupied zone of Germany

Following the German unconditional surrender, Eisenhower was appointed military governor of the American-occupied zone of Germany, located primarily in

Southern Germany, and

headquartered in

Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

. Upon discovery of the

Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps (), including subcamp (SS), subcamps on its own territory and in parts of German-occupied Europe.

The first camps were established in March 1933 immediately af ...

, he ordered camera crews to document evidence for use in the

Nuremberg Trials #REDIRECT Nuremberg trials

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from move ...

. He reclassified German

prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

(POWs) in US custody as

Disarmed Enemy Forces

Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEF, less commonly, Surrendered Enemy Forces) is a US designation for soldiers who surrender to an adversary after hostilities end, and for those POWs who had already surrendered and were held in camps in occupied German ...

(DEFs), who were no longer subject to the

Geneva Convention. Eisenhower followed the orders laid down by the

Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and ...

(JCS) in directive

JCS 1067

The Morgenthau Plan was a proposal to weaken Germany following World War II by eliminating its arms industry and removing or destroying other key industries basic to military strength. This included the removal or destruction of all industrial ...

but softened them by bringing in 400,000 tons of food for civilians and allowing more

fraternization. In response to the devastation in Germany, including food shortages and an influx of refugees, he arranged distribution of American food and medical equipment. His actions reflected the new American attitudes of the German people as Nazi victims not villains, while aggressively purging the ex-Nazis.

Army Chief of Staff

In November 1945, Eisenhower returned to Washington to replace Marshall as

Chief of Staff of the Army. His main role was the rapid demobilization of millions of soldiers, which was delayed by lack of shipping. Eisenhower was convinced in 1946 that the Soviet Union did not want war and that friendly relations could be maintained; he strongly supported the new United Nations and favored its involvement in the control of atomic bombs. However, in formulating policies regarding the

atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

and relations with the Soviets, Truman was guided by the State Department and ignored Eisenhower and the

Pentagon

In geometry, a pentagon () is any five-sided polygon or 5-gon. The sum of the internal angles in a simple polygon, simple pentagon is 540°.

A pentagon may be simple or list of self-intersecting polygons, self-intersecting. A self-intersecting ...

. Indeed, Eisenhower had opposed the use of the atomic bomb against the Japanese, writing, "First, the Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn't necessary to hit them with that awful thing. Second, I hated to see our country be the first to use such a weapon." Initially, Eisenhower hoped for cooperation with the Soviets.

He even visited

Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

in 1945. Invited by

Bolesław Bierut

Bolesław Bierut (; 18 April 1892 – 12 March 1956) was a Polish communist activist and politician, leader of History of Poland (1945–1989), communist-ruled Poland from 1947 until 1956. He was President of the State National Council from 1944 ...

and decorated with the

highest military decoration, he was shocked by the scale of destruction in the city. However, by mid-1947, as east–west tensions over economic recovery in Germany and the

Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War () took place from 1946 to 1949. The conflict, which erupted shortly after the end of World War II, consisted of a Communism, Communist-led uprising against the established government of the Kingdom of Greece. The rebels decl ...

escalated, Eisenhower agreed with a

containment policy to stop Soviet expansion.

1948 presidential election

In June 1943, a visiting politician had suggested to Eisenhower that he might become president after the war. Believing that a general should not participate in politics,

Merlo J. Pusey wrote that "figuratively speaking,

isenhowerkicked his political-minded visitor out of his office". As others asked him about his political future, Eisenhower told one that he could not imagine wanting to be considered for any political job "from dogcatcher to Grand High Supreme King of the Universe", and another that he could not serve as Army Chief of Staff if others believed he had political ambitions. In 1945, Truman told Eisenhower during the

Potsdam Conference that if desired, the president would help the general win the

1948 election,

and in 1947 he offered to run as Eisenhower's running mate on the Democratic ticket if MacArthur won the Republican nomination.

[Truman Wrote of '48 Offer to Eisenhower]

" ''The New York Times'', July 11, 2003.

As the election approached, other prominent citizens and politicians from both parties urged Eisenhower to run. In January 1948, after learning of plans in

New Hampshire

New Hampshire ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

to elect delegates supporting him for the forthcoming

Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention (RNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1856 by the Republican Party in the United States. They are administered by the Republican National Committee. The goal o ...

, Eisenhower stated through the Army that he was "not available for and could not accept nomination to high political office"; "life-long professional soldiers", he wrote, "in the absence of some obvious and overriding reason,

houldabstain from seeking high political office". Eisenhower maintained no political party affiliation during this time. Many believed he was forgoing his only opportunity to be president as Republican

Thomas E. Dewey was considered the probable winner and would presumably serve two terms, meaning that Eisenhower, at age 66 in 1956, would be too old to run.

President at Columbia University and NATO Supreme Commander

In 1948, Eisenhower became President of

Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

, an

Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate List of NCAA conferences, athletic conference of eight Private university, private Research university, research universities in the Northeastern United States. It participates in the National Collegia ...

university in New York City, where he was inducted into

Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

. The choice was subsequently characterized as not having been a good fit for either party. During that year, Eisenhower's memoir, ''

Crusade in Europe'', was published. It was a major financial success.

Eisenhower sought the advice of Augusta National's Roberts about the tax implications of this,

and in due course Eisenhower's profit on the book was substantially aided by what author

David Pietrusza

David Pietrusza is an American author and historian, and is considered an expert on US Politics in the 1920s.

He has written a number of books, including ''Roosevelt Sweeps Nation: FDR's 1936 Landslide and the Triumph of the Liberal Ideal,'' w ...

calls "a ruling without precedent" by the

Department of the Treasury. It held that Eisenhower was not a professional writer, but rather, marketing the lifetime asset of his experiences, and thus he had to pay only capital gains tax on his $635,000 advance instead of the much higher personal tax rate. This ruling saved Eisenhower about $400,000.

Eisenhower's stint as the president of Columbia was punctuated by his activity within the

Council on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an American think tank focused on Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy and international relations. Founded in 1921, it is an independent and nonpartisan 501(c)(3) nonprofit organi ...

, a study group he led concerning the political and military implications of the

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

and

The American Assembly, Eisenhower's "vision of a great cultural center where business, professional and governmental leaders could meet from time to time to discuss and reach conclusions concerning problems of a social and political nature".

His biographer