Edwin Taylor Pollock on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edwin Taylor Pollock (October 25, 1870June 4, 1943) was a career

In the final days before the entrance of the

In the final days before the entrance of the

On November 30, 1921, Pollock was transferred from command of ''Oklahoma'' to become the Military Governor of

On November 30, 1921, Pollock was transferred from command of ''Oklahoma'' to become the Military Governor of

Immediately on leaving Samoa, Pollock was appointed superintendent of the

Immediately on leaving Samoa, Pollock was appointed superintendent of the

officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," fro ...

in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

, serving in the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

and in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. He was later promoted to the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

.

As a young ensign

Ensign most often refers to:

* Ensign (flag), a flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality

* Ensign (rank), a navy (and former army) officer rank

Ensign or The Ensign may also refer to:

Places

* Ensign, Alberta, Alberta, Canada

* Ensign, Ka ...

, Pollock served aboard during the Spanish–American War. After the war, he rose through the ranks, served on several ships, and did important research into wireless communication. In 1917, less than a week before the United States entered World War I, he won a race against a fellow officer to receive the U.S. Virgin Islands

The United States Virgin Islands, officially the Virgin Islands of the United States, are a group of Caribbean islands and a territory of the United States. The islands are geographically part of the Virgin Islands archipelago and are located ...

from Denmark, and served as the territory's first acting governor. During the war, he was promoted to captain and a vessel under his command transported 60,000 American soldiers to France, for which he was awarded a Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Naval Service's second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is equivalent to the Army ...

. Afterward, he was made the eighth Naval Governor of American Samoa

American Samoa is an Territories of the United States, unincorporated and unorganized territory of the United States located in the Polynesia region of the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. Centered on , it is southeast of the island count ...

and then the superintendent of the United States Naval Observatory

The United States Naval Observatory (USNO) is a scientific and military facility that produces geopositioning, navigation and timekeeping data for the United States Navy and the United States Department of Defense. Established in 1830 as the ...

, before retiring in 1927.

As Governor of American Samoa, Pollock is notable for establishing dialogue with the Mau movement

The Mau was a nonviolence, non-violent movement for Samoan independence from colony, colonial rule during the first half of the 20th century. ''Mau'' means 'resolute' or 'resolved' in the sense of 'opinion', 'unwavering', 'to be decided', o ...

, which eventually led to the dissolution of opposition groups. He firmly denied entry to C.S. Hannum and Samuel S. Ripley, believing their presence would cause even greater trouble than in 1920, and vowed to jail Hannum if he ever returned to American Samoa. Pollock also prohibited the use of Samoan bush medicine and instituted a special tax of $3 per taxpayer. Additionally, he is remembered for giving the final approval for the hanging of Toeupu following his murder conviction. In 1923, Governor Pollock made the first proposal for a museum in American Samoa. This was included in his 1923 report to the Secretary of the Navy. However, work on the museum was not started until the arrival of First Lady Jean P. Haydon in 1969.

Early career

Originally fromMount Gilead, Ohio

Mount Gilead is a village in and the county seat of Morrow County, Ohio, United States. It is located northeast of Columbus. The population was 3,503 at the 2020 census. It is the center of population of Ohio. The village was established in 1 ...

, Pollock attended the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as United States Secre ...

and, as a midshipman, was assigned to and .; He graduated with a rank of ensign

Ensign most often refers to:

* Ensign (flag), a flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality

* Ensign (rank), a navy (and former army) officer rank

Ensign or The Ensign may also refer to:

Places

* Ensign, Alberta, Alberta, Canada

* Ensign, Ka ...

in 1893.

After graduation, Pollock returned to Ohio and married Beatrice E. Law Hale on December 5. Two weeks later, he was assigned to the cruiser during its initial shake-down. He was subsequently assigned to the gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

for an expedition to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. He remained in China for two and a half years as part of the Asiatic Squadron

The Asiatic Squadron was a squadron (naval), squadron of United States Navy warships stationed in East Asia during the latter half of the 19th century. It was created in 1868 when the East India Squadron was disbanded. Vessels of the squadron w ...

, then transferring to before returning home in 1897. On his return home, the Spanish–American War was heating up and he was reassigned to ''New York'', to see service in Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

and Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

, eventually taking part in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba

The Battle of Santiago de Cuba was a decisive naval engagement that occurred on July 3, 1898 between an United States, American fleet, led by William T. Sampson and Winfield Scott Schley, against a Restoration (Spain), Spanish fleet led by Pascu ...

.

In January 1900, he was promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

and assigned to . Over the following year he served on and .; On board ''Buffalo'', he returned to the Asiatic Squadron near China and was finally transferred to , the squadron's flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

. He remained on board ''Brooklyn'', until its return home in May 1902. After a brief leave, Pollock was assigned to the USS ''Chesapeake'' (as the watch

A watch is a timepiece carried or worn by a person. It is designed to maintain a consistent movement despite the motions caused by the person's activities. A wristwatch is worn around the wrist, attached by a watch strap or another type of ...

and division officer

A division officer (known as a divisional officer in the UK) commands a shipboard division of enlisted personnel, and is typically the lowest ranking officer in their administrative chain of command. Enlisted personnel aboard United States Nav ...

), a position he held for more than one year. He was transferred to , serving for another year, and then to Cavite Naval Base

Naval Station Pascual Ledesma, also known as Cavite Naval Base or Cavite Navy Yard, is a military installation of the Philippine Navy in Cavite City.

In the 1940s and '50s, it was called Philippine Navy Operating Base. The naval base is located ...

.; At Cavite, he was promoted to lieutenant commander in February 1906.;

His first duty as a lieutenant commander was on , as the navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's prim ...

. In 1910, Pollock was reassigned to , where he was promoted to commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

in March 1911.

On his promotion, Pollock commanded and , before being transferred to the United States Naval Observatory

The United States Naval Observatory (USNO) is a scientific and military facility that produces geopositioning, navigation and timekeeping data for the United States Navy and the United States Department of Defense. Established in 1830 as the ...

.; During his command of ''Kearsarge'', Pollock briefly commanded for a world-record setting wireless experiment. For this feat, ''Salem'' was outfitted with 16 different wireless telegraph technologies and sailed to Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

, with Pollock commanding. On arrival, they tested these technologies and set a world-record for longest wireless telegraph distance, , using a "Poulsen Apparatus", based on principles by Valdemar Poulsen

Valdemar Poulsen (23 November 1869 – 23 July 1942) was a Danish engineer who developed a magnetic wire recorder called the telegraphone in 1898. He also made significant contributions to early radio technology, including the first continuous w ...

. Experiments were also conducted to determine wireless characteristics during inclement weather and during both the day and night. In 1916, he was put in command of , the ship on which he had been the navigator.

U.S. Virgin Islands

In the final days before the entrance of the

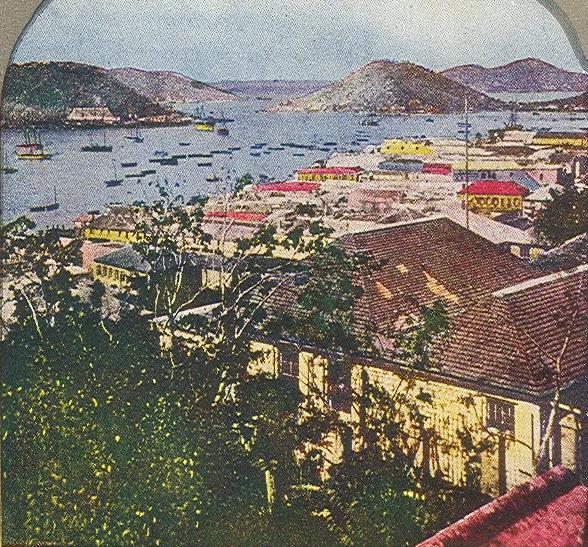

In the final days before the entrance of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

into World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the U.S. military was concerned that Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

was planning to purchase or seize the Danish West Indies

The Danish West Indies () or Danish Virgin Islands () or Danish Antilles were a Danish colony in the Caribbean, consisting of the islands of Saint Thomas with , Saint John () with , Saint Croix with , and Water Island.

The islands of St ...

for use as a submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

or zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp. 155� ...

base. At the time, Charlotte Amalie on Saint Thomas was considered the best port in the Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

outside of Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, and Coral Bay on Saint John was considered the safest harbor in the area. Although the United States was not yet at war with Germany, the U.S. signed a treaty to purchase the territory from Denmark for 25 million dollars on March 28, 1917. President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

nominated James Harrison Oliver to be the first military governor. The United States announced plans to build a naval base in the territory to aid in the protection of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

.

Oliver was unable to travel immediately to the Islands and the honor of being the first Acting Governor of the United States Virgin Islands

The United States Virgin Islands, officially the Virgin Islands of the United States, are a group of Caribbean islands and a territory of the United States. The islands are geographically part of the Virgin Islands archipelago and are located ...

was decided in an unusual way. Both Pollock, commanding , and B. B. Blerer's were dispatched to the Islands in a race. The commander of the ship that arrived first would officiate at the transfer ceremony and be acting governor. Pollock arrived first and the transfer ceremony took place on March 31, 1917, on Saint Thomas. Blerer officiated at a smaller ceremony on Saint Croix

Saint Croix ( ; ; ; ; Danish language, Danish and ; ) is an island in the Caribbean Sea, and a county and constituent Districts and sub-districts of the United States Virgin Islands, district of the United States Virgin Islands (USVI), an Unin ...

. Present for the handover was the crew of the Danish station cruiser ''Valkyrien'' and the former island legislature. The United States declared war on Germany on April 6, less than a week after securing the islands. Oliver was confirmed by Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

on April 20 and relieved Pollock as governor.

World War I

During the war, Pollock was appointed as captain on , a German cruise liner which was seized by the United States government for use as a military transport ship. She was rechristened ''George Washington'' in September 1917 and Pollock was given her command on October 1, 1917. That December, she set out with her first load of troops. During the war, Pollock successfully transported 60,000 American soldiers toFrance

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

in 18 round trips. In 1918, ''George Washington'' was tasked to deliver President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

to the Paris Peace Conference, though Pollock would not make the trip. He was reassigned on September 29, 1918.

While on board ''George Washington'', Pollock and Chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intellige ...

Paul F. Bloomhardt edited a daily newspaper

A newspaper is a Periodical literature, periodical publication containing written News, information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background. Newspapers can cover a wide variety of fields such as poli ...

. After the war, stories from the paper were assembled and published in 1919 by J. J. Little & Ives co. as ''Hatchet of the United States Ship "George Washington"''. A short review of the work by ''Outlook

Outlook or The Outlook may refer to:

Computing

* Microsoft Outlook, also referred to as ''the classic Outlook'' an e-mail client and personal information management software product from Microsoft

* Outlook for Windows, also referred to as ''the ...

'' magazine called the book "readable" and "admirably illustrated". It "abounds in clever bits of fun, queer and notable incidents, and sound and patriotic editorials."

After the war, he was eventually reassigned to the battleship , to serve in the Pacific fleet. On November 10, 1920, Pollock was awarded a Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Naval Service's second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is equivalent to the Army ...

for his services during the war.

American Samoa

On November 30, 1921, Pollock was transferred from command of ''Oklahoma'' to become the Military Governor of

On November 30, 1921, Pollock was transferred from command of ''Oklahoma'' to become the Military Governor of American Samoa

American Samoa is an Territories of the United States, unincorporated and unorganized territory of the United States located in the Polynesia region of the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. Centered on , it is southeast of the island count ...

. Events both personal and political had led to a previous governor, Warren Terhune's, suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death.

Risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse. Some suicides are impulsive acts driven by stress (such as from financial or ac ...

on November 3, 1920, and the appointment of Governor Waldo A. Evans to conduct a court of inquiry into the situation and to restore order. Pollock succeeded Evans, who had successfully restored the government and productivity of the islands after a period of unrest. At this time, American Samoa was administered by a team of twelve officers and a governor, with a total population of approximately 8,000 people. The islands were primarily important due to the excellent harbor

A harbor (American English), or harbour (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is a sheltered body of water where ships, boats, and barges can be moored. The term ''harbor'' is often used interchangeably with ''port'', which is ...

at Pago Pago

Pago Pago ( or ; Samoan language, Samoan: )Harris, Ann G. and Esther Tuttle (2004). ''Geology of National Parks''. Kendall Hunt. Page 604. . is the capital of American Samoa. It is in Maoputasi County, American Samoa, Maoputasi County on Tutuila ...

.

Beginning in 1920, a Mau movement

The Mau was a nonviolence, non-violent movement for Samoan independence from colony, colonial rule during the first half of the 20th century. ''Mau'' means 'resolute' or 'resolved' in the sense of 'opinion', 'unwavering', 'to be decided', o ...

, from the Samoan word for "opposition", was forming in American Samoa in protest of several Naval government policies, some of which had been implemented by Terhune but which were not revoked following his death, which natives (and some non-natives) found heavy-handed. The movement itself may have been inspired by a different and older Mau movement in nearby Western Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa and known until 1997 as Western Samoa, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania, in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu), two smaller, inhabit ...

, against the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

and then New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

colonial powers. Some of the initial grievances of the movement included the quality of roads in the territory, a marriage law which largely forbade natives from marrying non-natives, and a justice system which discriminated against locals in part because laws were not often available in Samoan. In addition, the United States Navy also prohibited an assembly of Samoan chiefs, whom the movement considered the real government of the territory. Surprisingly, the movement had grown to include several prominent officers of former Governor Terhune's staff, including his executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization.

In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer ...

. It culminated in a proclamation by Samuel S. Ripley, an American Samoan from an ''afakasi'' or mixed-blood Samoan family, with large communal property in the islands, that he was the leader of a legitimate successor government to pre-1899 Samoa. Evans also met with the high chiefs and secured their assent to continued Naval government. Ripley, who had traveled to Washington to meet with Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

Edwin C. Denby, was not permitted by Evans to enter the port at American Samoa and returned to exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

in California, where he later became the mayor of Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

.

After being appointed as governor, Pollock's continued the colonization work started by his predecessor. Prior to traveling to the territory, he met with Ripley in San Francisco, California

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

. Although Ripley maintained that American "occupation" of Samoa was usurpation, he agreed to allow Pollock to govern unfettered and to provide him with copies of his letters. Almost immediately after arriving on the island, Pollock and Secretary of Native Affairs S. D. Hall met with representatives of the Mau, becoming the first governor to do so. Shortly afterwards, some members of the Mau disbanded, though the movement would continue in some form for another 13 years.

In June 1923, Governor Pollock recounted an unusual event from May 8, 1923, in a letter to the Department of the U.S. Navy. The story involved the capture of a "wild man" by a young Samoan in the hills north of Pago Pago

Pago Pago ( or ; Samoan language, Samoan: )Harris, Ann G. and Esther Tuttle (2004). ''Geology of National Parks''. Kendall Hunt. Page 604. . is the capital of American Samoa. It is in Maoputasi County, American Samoa, Maoputasi County on Tutuila ...

. The "wild man," clad only in nature’s vestments, was seen descending a coconut tree and was subdued by the Samoan, who bound his hands and brought him to the Naval Station. The captured individual became a sensation among both the Samoans and the white residents of the area. The young Samoan who made the capture was an escaped prisoner. After returning to the Naval Station, the "wild man" refused to separate from his captor for any significant length of time. Despite efforts, no one was able to communicate with him. It was apparent that they spoke different languages. The "wild man," who appeared to be quite elderly with nearly white hair, was physically frail but seemed content and at peace in his new surroundings, where he was well treated. Before long, Samoan residents recognized the so-called “wild man” as Malua, the fourth and final runaway survivor from the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands, also known simply as the Solomons,John Prados, ''Islands of Destiny'', Dutton Caliber, 2012, p,20 and passim is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 1000 smaller islands in Melanesia, part of Oceania, t ...

. He had been roaming the mountains around Pago Pago ever since his companion had sought refuge in 1901. Malua is buried at the Satala Cemetery.https://npshistory.com/publications/npsa/brochures/naval-ww2-history.pdf

Pollock's remaining time as governor was less eventful. While exploring Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

in May 1923, he discovered a turtle which had been branded by Captain Cook

Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 1768 and 1779. He complet ...

on his expedition there in 1773. The turtle was thus known to have lived more than 150 years. He was ordered home on July 26, 1923.

United States Naval Observatory

Immediately on leaving Samoa, Pollock was appointed superintendent of the

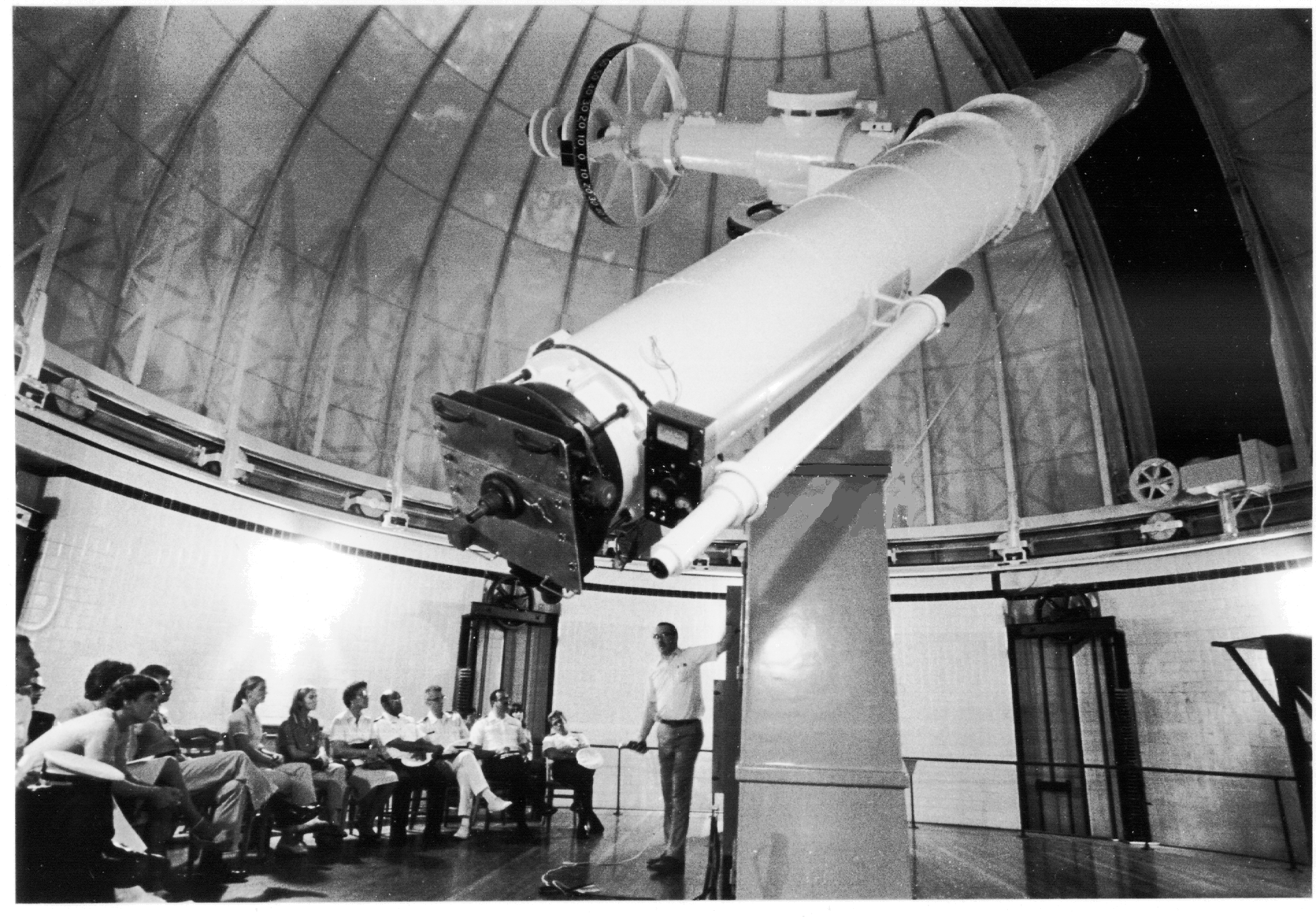

Immediately on leaving Samoa, Pollock was appointed superintendent of the United States Naval Observatory

The United States Naval Observatory (USNO) is a scientific and military facility that produces geopositioning, navigation and timekeeping data for the United States Navy and the United States Department of Defense. Established in 1830 as the ...

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, replacing outgoing Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

William D. MacDougal.

On August 22, 1924, Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

came within of Earth. The U.S. Naval Observatory made no formal observations of the planet, but Pollock and the son of astronomer Asaph Hall

Asaph Hall III (October 15, 1829 – November 22, 1907) was an American astronomer who is best known for having discovered the two moons of Mars, Deimos and Phobos, in 1877. He determined the orbits of satellites of other planets and of doubl ...

ceremonially re-enacted Hall's 1877 discoveries of the moons Phobos and Deimos

Deimos, a Greek word for ''dread'', may refer to:

In general

* Deimos (deity), one of the sons of Ares and Aphrodite in Greek mythology

* Deimos (moon), the smaller and outermost of Mars' two natural satellites

Fictional characters

* Deimos (comi ...

with his original telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, Absorption (electromagnetic radiation), absorption, or Reflection (physics), reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally, it was an optical instrument using len ...

. They also made observations to calculate the masses of the two moons.

On January 24, 1925, Pollock commanded the dirigible

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat ( lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding ...

on a flight from Lakehurst, New Jersey

Lakehurst is a borough in Ocean County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 United States census, the borough's population was 2,636, a decrease of 18 (−0.7%) from the 2010 census count of 2,654, which in turn reflected an increa ...

, to photograph a solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs approximately every six months, during the eclipse season i ...

from an altitude of . This was the first time an eclipse had been photographed from the air.

After retirement

Pollock retired from service in 1927 and was replaced as superintendent by Captain Charles F. Freeman. In 1930, Pollock and his wife purchased a summer home in Jamestown, Rhode Island, while continuing to maintain their main residence in Washington, D.C. In 1932, he was made a director of the Jamestown Historical Society. He also became interested in genealogy and published several works on his family's history through the 1930s. He died on June 4, 1943, after a long illness and was buried inArlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the United States National Cemetery System, one of two maintained by the United States Army. More than 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington County, Virginia.

...

on June 7, 1943.

Works

* ''Hatchet of the United States Ship "George Washington"'', edited by Pollock and Paul F. Bloomhardt. A compilation of stories from ''The Hatchet'', a daily printed on board ''George Washington'' during the First World War. Published 1919.References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Pollock, E. T. 1870 births 1943 deaths Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Governors of American Samoa Governors of the United States Virgin Islands People from Mount Gilead, Ohio Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) United States Naval Academy alumni United States Navy officers