Edwin Stephen Goodrich on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edwin Stephen Goodrich FRS (

When Lankester became Linacre Professor of Comparative Anatomy at

When Lankester became Linacre Professor of Comparative Anatomy at

''The Vertebrata Craniata (Cyclostomes and Fishes).''

Volume IX of Lankester E. Ray (ed) ''Treatise on Zoology'', London. *Goodrich, Edwin S. 1924

''Living organisms: an account of their origin and evolution''

Oxford University Press. *Goodrich E.S. 1930

''Studies on the structure and development of Vertebrates''

Macmillan, London. xxx+837p, 754 figures. One of the great works of vertebrate comparative anatomy. *Goodrich E.S. 1895

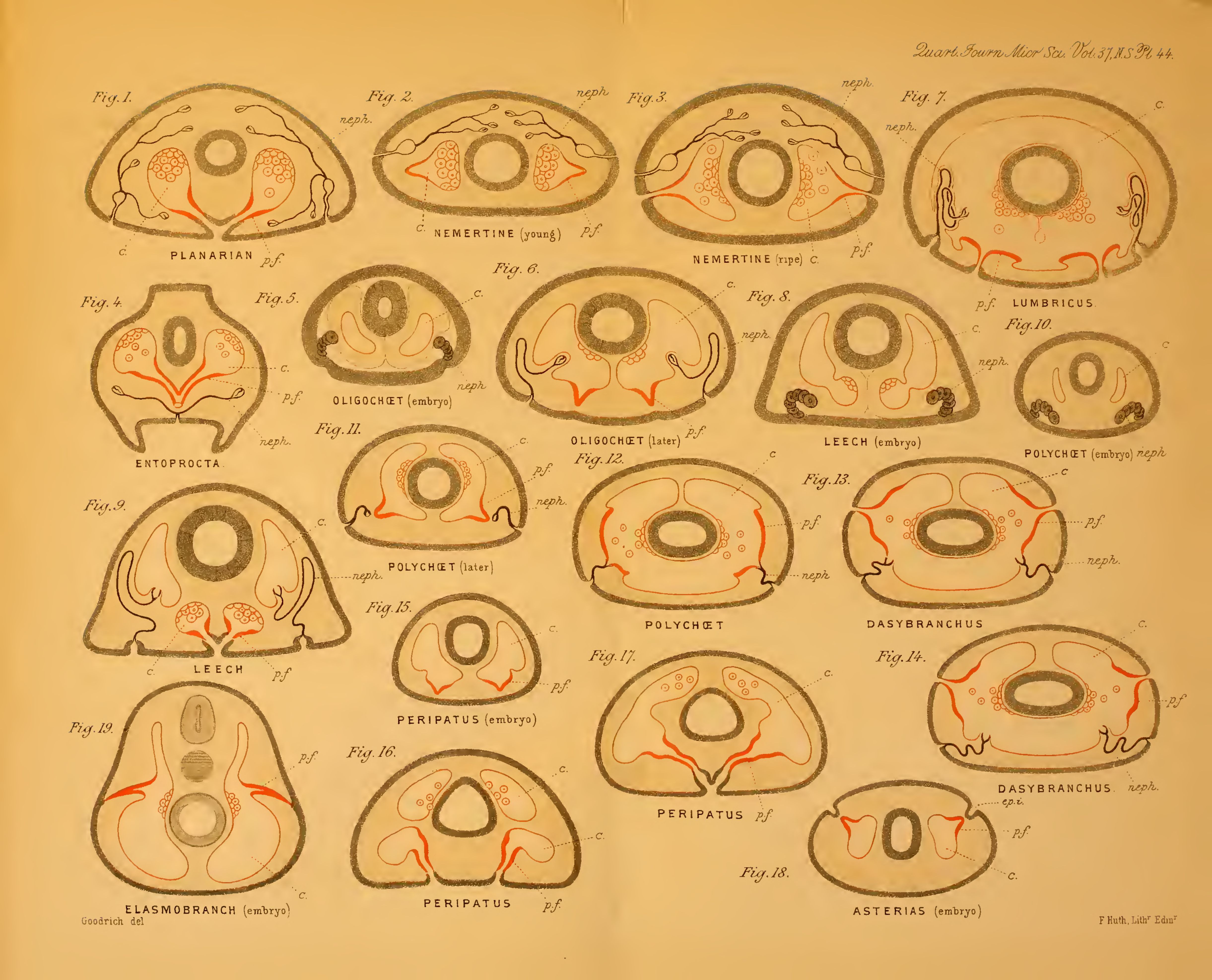

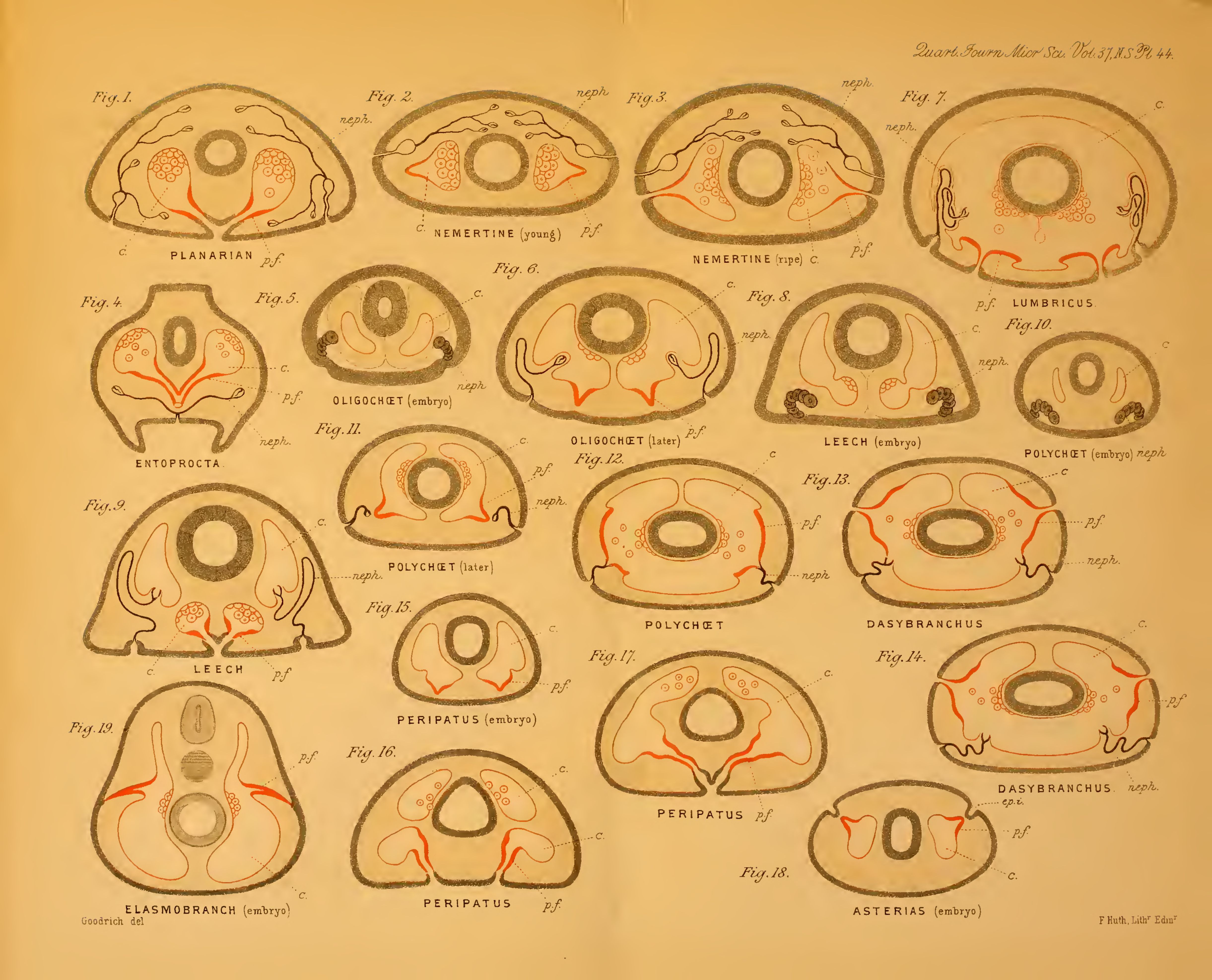

''On the coelom, genital ducts, and nephridia''.

''Q.J.M.S.'' 37, 477–510. *Goodrich E.S. 1913

''Metameric segmentation and homology''

''Q.J.M.S.'' 59, 227–248. *Goodrich E.S. 1927. The problem of the sympathetic nervous system from the morphological point of view. ''Proceedings of the Anatomical Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Journal of Anatomy'' 61, p499. *Goodrich E.S. 1934. The early development of the nephridia in ''Amphioxus'', Introduction and part I: Hatschek's Nephridium. ''Q.J.M.S''. 76, 499–510. *Goodrich E.S. 1934. 'The early development of the nephridia in ''Amphioxus'', part II: The paired nephridia. ''Q.J.M.S''. 76, 655–674. *Goodrich E.S. 1945. The study of nephridia and genital ducts since 1895. ''Q.J.M.S.'' 86, 113–392.

Dictionary of Scientific Biography

– biography by

Weston-super-Mare

Weston-super-Mare ( ) is a seaside town and civil parish in the North Somerset unitary district, in the county of Somerset, England. It lies by the Bristol Channel south-west of Bristol between Worlebury Hill and Bleadon Hill. Its population ...

, 21 June 1868 – Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, 6 January 1946), was an English zoologist

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the structure, embryology, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct, and how they interact with their ecosystems. Zoology is one ...

, specialising in comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

, embryology

Embryology (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἔμβρυον, ''embryon'', "the unborn, embryo"; and -λογία, ''-logy, -logia'') is the branch of animal biology that studies the Prenatal development (biology), prenatal development of gametes (sex ...

, palaeontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geo ...

, and evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

. He held the Linacre Chair of Zoology in the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

from 1921 to 1946. He served as editor of the '' Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science'' from 1920 until his death.

Life

Goodrich's father died when he was only two weeks old, and his mother took her children to live with her mother at Pau, France, where he attended the local English school and a French lycée. In 1888 he entered the Slade School of Art atUniversity College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

; there he met E. Ray Lankester, who interested him in zoology.

On coming to Oxford from London, Goodrich entered Merton College, Oxford

Merton College (in full: The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford) is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Its foundation can be traced back to the 126 ...

as an undergraduate in 1891 and, while acting as assistant to Lankester, read for the final honour school in Zoology; he was awarded the Rolleston Memorial Prize in 1894 and graduated with first-class honours the following year.

In 1913 Goodrich married Helen Pixell, a distinguished protozoologist, who helped greatly with his work. His artistic training always stood him in good stead. He drew diagrams of beauty and clarity whilst lecturing (students used to photograph the blackboard before it was erased), and in his books and papers. He also exhibited his watercolor

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour (Commonwealth English; see American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin 'water'), is a painting metho ...

landscapes in London. Goodrich was elected Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

in 1905 and received its Royal Medal

The Royal Medal, also known as The Queen's Medal and The King's Medal (depending on the gender of the monarch at the time of the award), is a silver-gilt medal, of which three are awarded each year by the Royal Society. Two are given for "the mo ...

in 1936. He was honorary member of the New York Academy of Science and of many other academies, and awarded many honorary doctorates. In 1945 Lev Berg

Lev Semyonovich Berg, also known as Leo S. Berg (; 14 March 1876 – 24 December 1950) was a leading Russian geographer, biologist and ichthyologist who served as President of the Soviet Geographical Society between 1940 and 1950.

He is known f ...

of Leningrad

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

sent a message through Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley (22 June 1887 – 14 February 1975) was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist and Internationalism (politics), internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentiet ...

: "Please tell oodrichthat... we all regard ourselves as his pupils." A small, dapper, thin man with a dry sense of humor, he always complained that, when travelling by air, he was not weighed with his luggage, since his own weight was only half that of an average passenger.

Career

When Lankester became Linacre Professor of Comparative Anatomy at

When Lankester became Linacre Professor of Comparative Anatomy at Merton College

Merton College (in full: The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Its foundation can be traced back to the 1260s when Walter de Merton, chancellor ...

, he made Goodrich his assistant in 1892; this marked the start of the researches which during half a century made Goodrich the greatest comparative anatomist of his day. In 1921 Goodrich was appointed to his mentor's old post, which he held until 1945.

From the start of his researches, many of which were devoted to marine organisms, Goodrich made himself acquainted at first hand with the marine fauna of Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

, Roscoff, Banyuls, Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

, Helgoland

Heligoland (; , ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , ) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. The islands were historically possessions of Denmark, then became possessions of the United Kingdom from 1807 to 1890. Since 1890, the ...

, Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

, Madeira

Madeira ( ; ), officially the Autonomous Region of Madeira (), is an autonomous Regions of Portugal, autonomous region of Portugal. It is an archipelago situated in the North Atlantic Ocean, in the region of Macaronesia, just under north of ...

, and the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; ) or Canaries are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean and the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, Autonomous Community of Spain. They are located in the northwest of Africa, with the closest point to the cont ...

. He also travelled extensively in Europe, the United States, North Africa, India, Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

, Malaya, and Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

. He worked out the significance of the tubes connecting the centres of the bodies of animals with the outside. There are nephridia

The nephridium (: nephridia) is an invertebrate organ, found in pairs and performing a function similar to the vertebrate kidneys (which originated from the chordate nephridia). Nephridia remove metabolic wastes from an animal's body. Nephridia co ...

, developed from the outer layer inward and serving the function of excretion

Excretion is elimination of metabolic waste, which is an essential process in all organisms. In vertebrates, this is primarily carried out by the lungs, Kidney (vertebrates), kidneys, and skin. This is in contrast with secretion, where the substa ...

. Quite different from them are coelomoducts, developed from the middle layer outward, serving to release the germ cell

A germ cell is any cell that gives rise to the gametes of an organism that reproduces sexually. In many animals, the germ cells originate in the primitive streak and migrate via the gut of an embryo to the developing gonads. There, they unde ...

s. These two sets of tubes may look similar, when each opens into the body cavity through a funnel surrounded by cilia which create a current of fluid. In some groups the nephridia may disappear (as in vertebrates, where the nephridia may have been converted into the thymus gland), and the coelomoducts then take on the additional function of excretion. This is why man has a genitourinary system. Before Goodrich's analysis, the whole subject was in chaos.

Goodrich established that a motor nerve

A motor nerve, or efferent nerve, is a nerve that contains exclusively efferent nerve fibers and transmits motor signals from the central nervous system (CNS) to the effector organs (muscles and glands), as opposed to sensory nerves, which transf ...

remains linked to its corresponding segmental muscle, however much it may have become displaced or obscured in development. He showed that organs can be homologous without arising from the same segments of the body. For example, the fins and limbs of vertebrates; and the occipital arch (the back of the skull), which varies in vertebrates from the fifth to the ninth segment.

He distinguished between the scale structures of fishes, living and fossil, by which they are classified and recognised. This is important because different strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum (: strata) is a layer of Rock (geology), rock or sediment characterized by certain Lithology, lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by v ...

may identified by fossil fish scales. Goodrich's attention was always focused on evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

, to which he made notable contributions, firmly adhering to Darwin's theory of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

.

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

in May 1905.

On his seventieth birthday, in 1938, his colleagues and pupils published a festschrift

In academia, a ''Festschrift'' (; plural, ''Festschriften'' ) is a book honoring a respected person, especially an academic, and presented during their lifetime. It generally takes the form of an edited volume, containing contributions from the h ...

a volume of essays in his honour edited by Gavin de Beer: ''Evolution: essays on aspects of evolutionary biology''.

Selected works

*Goodrich E.S. 1909''The Vertebrata Craniata (Cyclostomes and Fishes).''

Volume IX of Lankester E. Ray (ed) ''Treatise on Zoology'', London. *Goodrich, Edwin S. 1924

''Living organisms: an account of their origin and evolution''

Oxford University Press. *Goodrich E.S. 1930

''Studies on the structure and development of Vertebrates''

Macmillan, London. xxx+837p, 754 figures. One of the great works of vertebrate comparative anatomy. *Goodrich E.S. 1895

''On the coelom, genital ducts, and nephridia''.

''Q.J.M.S.'' 37, 477–510. *Goodrich E.S. 1913

''Metameric segmentation and homology''

''Q.J.M.S.'' 59, 227–248. *Goodrich E.S. 1927. The problem of the sympathetic nervous system from the morphological point of view. ''Proceedings of the Anatomical Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Journal of Anatomy'' 61, p499. *Goodrich E.S. 1934. The early development of the nephridia in ''Amphioxus'', Introduction and part I: Hatschek's Nephridium. ''Q.J.M.S''. 76, 499–510. *Goodrich E.S. 1934. 'The early development of the nephridia in ''Amphioxus'', part II: The paired nephridia. ''Q.J.M.S''. 76, 655–674. *Goodrich E.S. 1945. The study of nephridia and genital ducts since 1895. ''Q.J.M.S.'' 86, 113–392.

References

Further reading

Dictionary of Scientific Biography

– biography by

Gavin de Beer

Sir Gavin Rylands de Beer (1 November 1899 – 21 June 1972) was a British evolutionary embryologist, known for his work on heterochrony as recorded in his 1930 book ''Embryos and Ancestors''. He was director of the Natural History Museum, Lond ...

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Goodrich, Edwin Stephen 19th-century British zoologists Fellows of the Royal Society 1868 births 1946 deaths Royal Medal winners British embryologists English anatomists British evolutionary biologists Alumni of the Slade School of Fine Art Alumni of Merton College, Oxford Fellows of Merton College, Oxford Linacre Professors of Zoology Modern synthesis (20th century) 20th-century English zoologists British expatriates in France