Edwin M. Stanton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. secretary of war under the Lincoln Administration during most of the

In Steubenville, the Stantons welcomed two children. Their daughter, Lucy Lamson, was born in March 1840. Within months of her birth, Lucy was stricken with an unknown illness. Stanton put aside his work to spend that summer at baby Lucy's bedside. She died in 1841, shortly after her second birthday. Their son, Edwin L. Stanton, Edwin Lamson, was born in August 1842. The boy's birth refreshed the spirits in the Stanton household after baby Lucy's death. Unlike Lucy's early years, Edwin was healthy and active. Grief, however, would return once again to the Stanton household in 1844, when Mary Stanton was left bedridden by a

In Steubenville, the Stantons welcomed two children. Their daughter, Lucy Lamson, was born in March 1840. Within months of her birth, Lucy was stricken with an unknown illness. Stanton put aside his work to spend that summer at baby Lucy's bedside. She died in 1841, shortly after her second birthday. Their son, Edwin L. Stanton, Edwin Lamson, was born in August 1842. The boy's birth refreshed the spirits in the Stanton household after baby Lucy's death. Unlike Lucy's early years, Edwin was healthy and active. Grief, however, would return once again to the Stanton household in 1844, when Mary Stanton was left bedridden by a

In Pittsburgh, Stanton formed a partnership with a prominent retired judge, Charles Shaler, while maintaining his collaboration with McCook, who had remained in Steubenville after returning from service in the Mexican–American War. Stanton argued several high-profile suits. One such proceeding was ''State of Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont Bridge Company and others'' in the

In Pittsburgh, Stanton formed a partnership with a prominent retired judge, Charles Shaler, while maintaining his collaboration with McCook, who had remained in Steubenville after returning from service in the Mexican–American War. Stanton argued several high-profile suits. One such proceeding was ''State of Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont Bridge Company and others'' in the

A by-effect of Stanton's performance in ''Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont'' was that he was sought after for other prominent cases, such as the McCormick Reaper patent case of inventor

A by-effect of Stanton's performance in ''Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont'' was that he was sought after for other prominent cases, such as the McCormick Reaper patent case of inventor

Arguments for the trial began on April 4. The prosecution wanted to advance the theory that Sickles had also committed adultery and did not pay very much mind to his wife or her activities. When the judge disallowed this, the prosecution opted instead to highlight the heinous nature of Sickles' murder, and not address his reasons for doing the crime. Sickles' defense countered that Sickles had suffered from a temporary bout of insanity, the first successful such instance of an insanity plea in American jurisprudence. The events in the courtroom during the trial were nothing if not dramatic. When Stanton delivered closing arguments, stating that marriage is sacred and that a man should have the right to defend his marriage against those who chose to defile the purity of the sacrament, the courtroom erupted in cheers. A law student described Stanton's argument during the trial, "a typical piece of Victorian rhetoric, an ingenious thesaurus of aphorisms on the sanctity of the family." The jury in the case deliberated for just over an hour before declaring Sickles not guilty. The judge ordered that Sickles be released from his arrest. Outside the courthouse, Sickles, Stanton and company met a throng of individuals in adulation of the victory.

Arguments for the trial began on April 4. The prosecution wanted to advance the theory that Sickles had also committed adultery and did not pay very much mind to his wife or her activities. When the judge disallowed this, the prosecution opted instead to highlight the heinous nature of Sickles' murder, and not address his reasons for doing the crime. Sickles' defense countered that Sickles had suffered from a temporary bout of insanity, the first successful such instance of an insanity plea in American jurisprudence. The events in the courtroom during the trial were nothing if not dramatic. When Stanton delivered closing arguments, stating that marriage is sacred and that a man should have the right to defend his marriage against those who chose to defile the purity of the sacrament, the courtroom erupted in cheers. A law student described Stanton's argument during the trial, "a typical piece of Victorian rhetoric, an ingenious thesaurus of aphorisms on the sanctity of the family." The jury in the case deliberated for just over an hour before declaring Sickles not guilty. The judge ordered that Sickles be released from his arrest. Outside the courthouse, Sickles, Stanton and company met a throng of individuals in adulation of the victory.

On July 21st, the North and the South experienced their first major clash at Manassas Junction in Virginia, the

On July 21st, the North and the South experienced their first major clash at Manassas Junction in Virginia, the

In the final days of August 1862, Gen. Lee scourged Union forces, routing them at Manassas Junction in the

In the final days of August 1862, Gen. Lee scourged Union forces, routing them at Manassas Junction in the

Stanton found Lincoln at the

Stanton found Lincoln at the

Lt. Gen. Grant, failing to find Stanton at the War Department, sent a note to his home by courier on the evening of April 21. The matter was urgent. Maj. Gen. Sherman, who had established his army headquarters in

Lt. Gen. Grant, failing to find Stanton at the War Department, sent a note to his home by courier on the evening of April 21. The matter was urgent. Maj. Gen. Sherman, who had established his army headquarters in

On January 13, 1868, the Senate voted overwhelmingly to reinstate Stanton as Secretary of War. Grant, fearing the Act's prescribed penalty of $10,000 in fines and five-years of prison, doubly so because of his high likelihood of being the Republican presidential nominee in the upcoming election, turned the office over immediately. Stanton returned to the War Department soon after in "unusually fine spirits and chatting casually", as newspapers reported. His reemergence precipitated a tide of congratulatory writings and gestures, thanking him for his opposition to the greatly disliked Johnson. The president, meanwhile, again began searching for an agreeable person to take the helm at the War Department, but after a few weeks, he seemed to accept Stanton's reinstatement with resignation. He did try to diminish the power of Stanton's office, however, regularly disregarding it. However, with his ability to sign treasury warrants, and his backing by Congress, Stanton still held considerable power.

Johnson became singularly focused on enacting Stanton's downfall. "No longer able to bear the congressional insult of an enemy imposed on his Official family," Marvel says, "Johnson began to ponder removing Stanton outright and replacing him with someone palatable enough to win Senate approval." Johnson sought

On January 13, 1868, the Senate voted overwhelmingly to reinstate Stanton as Secretary of War. Grant, fearing the Act's prescribed penalty of $10,000 in fines and five-years of prison, doubly so because of his high likelihood of being the Republican presidential nominee in the upcoming election, turned the office over immediately. Stanton returned to the War Department soon after in "unusually fine spirits and chatting casually", as newspapers reported. His reemergence precipitated a tide of congratulatory writings and gestures, thanking him for his opposition to the greatly disliked Johnson. The president, meanwhile, again began searching for an agreeable person to take the helm at the War Department, but after a few weeks, he seemed to accept Stanton's reinstatement with resignation. He did try to diminish the power of Stanton's office, however, regularly disregarding it. However, with his ability to sign treasury warrants, and his backing by Congress, Stanton still held considerable power.

Johnson became singularly focused on enacting Stanton's downfall. "No longer able to bear the congressional insult of an enemy imposed on his Official family," Marvel says, "Johnson began to ponder removing Stanton outright and replacing him with someone palatable enough to win Senate approval." Johnson sought

Edwin Stanton was the second American other than a U.S. president to appear on a U.S. postage issue, the first being

Edwin Stanton was the second American other than a U.S. president to appear on a U.S. postage issue, the first being

in JSTOR

* Hendrick, Burton J. ''Lincoln's War Cabinet'' (1946). * Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve, and Kunhardt Jr., Phillip B. ''Twenty Days''. Castle Books, 1965. * * Meneely, A. Howard, "Stanton, Edwin McMasters", in ''Dictionary of American Biography'', Volume 9 (1935) * Pratt, Fletcher. ''Stanton: Lincoln's Secretary of War'' (1953). * * * * Simpson, Brooks D. ''Let Us Have Peace: Ulysses S. Grant and the Politics of War and Reconstruction, 1861–1868'' (1991) * Skelton, William B. "Stanton, Edwin McMasters"

''American National Biography Online'' 2000.

* Stahr, Walter, ''Stanton: Lincoln’s War Secretary'' (2017). New York: Simon & Schuster.

* Stanton, Edwin (Edited by Ben Ames Williams Jr.) ''Mr. Secretary'' (1940), partial autobiography. * *

Wife Of Secretary Of War Edwin Stanton

Mr. Lincoln and Friends: Edwin M. Stanton Biography.

Mr. Lincoln's White House: Edwin M. Stanton Biography.

* ttp://www.frbsf.org/currency/metal/treasury/index2.html Pictures of U.S. Treasury Notes featuring Edwin Stanton, provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Spartacus Educational: Edwin M. Stanton.

* , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Stanton, Edwin M. 1814 births 1869 deaths 19th-century American lawyers 19th-century American politicians American abolitionists Methodists from Ohio American people of English descent Andrew Johnson administration cabinet members Buchanan administration cabinet members Burials at Oak Hill Cemetery (Washington, D.C.) Impeachment of Andrew Johnson Kenyon College alumni Lincoln administration cabinet members Methodist abolitionists Ohio Democrats Ohio lawyers Ohio Republicans People associated with the assassination of Abraham Lincoln People from Cadiz, Ohio Politicians from Steubenville, Ohio People of Ohio in the American Civil War Stanton County, Nebraska Union (American Civil War) political leaders Attorneys general of the United States United States secretaries of war Unsuccessful nominees to the United States Supreme Court

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. Stanton's management helped organize the massive military resources of the North and guide the Union to victory. However, he was criticized by many Union generals, who perceived him as overcautious and a micromanager. He also organized the manhunt for Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

's assassin, John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, assassinated United States president Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the p ...

.

After Lincoln's assassination, Stanton remained as the secretary of war under the new U.S. president

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

, during the first years of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

. He opposed the lenient policies of Johnson towards the former Confederate States

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States from 1861 to 1865. It comprised eleven U.S. states th ...

. Johnson's attempt to dismiss Stanton ultimately led to Johnson being impeached by the Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans were a political faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They ca ...

in the House of Representatives. Stanton returned to law after he retired as secretary of war. In 1869, he was nominated as an associate justice of the Supreme Court by Johnson's successor, Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

, but Stanton died four days after his nomination was confirmed by the Senate. He remains the only confirmed nominee to accept but die before serving on the Court.

Family and early life

Ancestry

Before theAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

, Stanton's paternal ancestors, the Stantons and the Macys, both of whom were Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

, moved from Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

to North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

. In 1774, Stanton's grandfather, Benjamin Stanton, married Abigail Macy. Benjamin died in 1800. That year, Abigail moved to the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from part of the unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolution. Established ...

, accompanied by much of her family. Soon, Ohio was admitted to the Union

Admission to the Union is provided by the Admissions Clause of the United States Constitution in Article IV, Section 3, Clause 1, which authorizes the United States Congress to admit new states into the Union beyond the thirteen states that a ...

, and Macy proved to be one of the early developers of the new state. She bought a tract of land at Mount Pleasant, Ohio, from the government and settled there. One of her sons, David, became a physician in Steubenville, and married Lucy Norman, the daughter of a Virginia planter. Their marriage was met with the ire of Ohio's Quaker community, as Lucy was a Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

, and not a Quaker. This forced David Stanton to abandon the Quaker sect.

Early life and education

Edwin McMasters was born to David and Lucy Stanton on December 19, 1814, in Steubenville, Ohio, the first of their four children. Edwin's early formal education consisted of a private school and aseminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological college, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called seminarians) in scripture and theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as cle ...

behind the Stantons' residence, called "Old Academy". When he was ten, he was transferred to a school taught by a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

minister. It was also at ten that Edwin experienced his first asthma attack, a malady that would haunt him for life, sometimes to the point of convulsion. Because of his asthma he was unable to participate in highly physical activities, so he found interest in books and poetry. Edwin attended Methodist church services and Sunday school regularly. At the age of thirteen, Stanton became a full member of the Methodist church.

David Stanton's medical practice afforded him and his family a decent living. When David Stanton suddenly died in December 1827 at his residence, Edwin and family were left destitute. Edwin's mother opened a store in the front room of their residence, selling the medical supplies her husband left her, along with books, stationery

Stationery refers to writing materials, including cut paper, envelopes, continuous form paper, and other office supplies. Stationery usually specifies materials to be written on by hand (e.g., letter paper) or by equipment such as computer p ...

and groceries

A grocery store (American English, AE), grocery shop or grocer's shop (British English, BE) or simply grocery is a retail store that primarily retails a general range of food Product (business), products, which may be Fresh food, fresh or Food p ...

. The youthful Edwin was removed from school, and worked at the store of a local bookseller.

Stanton began his college studies at the Episcopal Church-affiliated Kenyon College

Kenyon College ( ) is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Gambier, Ohio, United States. It was founded in 1824 by Episcopal Bishop Philander Chase. It is the oldest private instituti ...

in 1831. At Kenyon, Stanton was involved in the college's Philomathesian Literary Society. Stanton sat on several of the society's committees and often partook in its exercises and debates. Stanton was forced to leave Kenyon just at the end of his third semester for lack of finances. At Kenyon, his support of President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

's actions during the 1832 Nullification Crisis, a hotly debated topic among the Philomathesians, led him into the Democratic Party. Further, Stanton's conversion to Episcopalianism and his revulsion of the practice of slavery were solidified there. After Kenyon, Stanton worked as a bookseller in Columbus. Stanton had hoped to obtain enough money to complete his final year at Kenyon. However, a small salary at the bookstore dashed the notion. He soon returned to Steubenville to pursue studies in law.

Early career and first marriage

Stanton studied law under the tutelage of Daniel Collier in preparation for the bar. He was admitted to practice in 1835, and began work at a prominentlaw firm

A law firm is a business entity formed by one or more lawyers to engage in the practice of law. The primary service rendered by a law firm is to advise consumer, clients (individuals or corporations) about their legal rights and Obligation, respon ...

in Cadiz, Ohio, under Chauncey Dewey, a well-known attorney. The firm's trial work often fell to him.

At the age of 18, Stanton met Mary Ann Lamson at Trinity Episcopal Church in Columbus, and they soon were engaged. After buying a home in Cadiz, Stanton went to Columbus where his betrothed was. Stanton and Lamson had wished to be married at Trinity Episcopal, but Stanton's illness rendered this idea moot. Instead, the ceremony was performed at the home of Trinity Episcopal's rector on December 31, 1836. Afterwards, Stanton went to Virginia where his mother and sisters were, and escorted the women back to Cadiz, where they would live with him and his wife.

After his marriage, Stanton partnered with the lawyer and federal judge Benjamin Tappan. Stanton's sister also married Tappan's son. In Cadiz, Stanton was situated prominently in the local community. He worked with the town's anti-slavery society, and with a local newspaper, the ''Sentinel'', writing and editing articles there. In 1837, Stanton was elected the prosecutor

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the adversarial system, which is adopted in common law, or inquisitorial system, which is adopted in Civil law (legal system), civil law. The prosecution is the ...

of Harrison County, on the Democratic ticket. Further, Stanton's increasing wealth allowed him to purchase a large tract of land in Washington County, and several tracts in Cadiz.

Rising attorney (1839–1860)

Return to Steubenville

Stanton's relationship with Benjamin Tappan expanded when Tappan was elected theUnited States senator

The United States Senate consists of 100 members, two from each of the 50 U.S. state, states. This list includes all senators serving in the 119th United States Congress.

Party affiliation

Independent Senators Angus King of Maine and Berni ...

from Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

in 1838. Tappan asked Stanton to oversee his law operations, which were based in Steubenville. When his time as county prosecutor was finished, Stanton moved back to the town. Stanton's work in politics also expanded. He served as a delegate at the Democrats' 1840 national convention in Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

, and was featured prominently in Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

's campaign in the 1840 presidential election, which Van Buren lost.

He was a member of Steubenville Lodge No. 45 in Steubenville, Ohio, and when he moved to Pittsburgh became a member of Washington Lodge No. 253 on 25 March 1852 as a charter member. He resigned on 29 Nov. 1859. pp. 189-81.“ (Denslow, William R. ''10,000 Famous Freemasons.'' Independence, Missouri: Missouri Lodge of Research, 1957. In Steubenville, the Stantons welcomed two children. Their daughter, Lucy Lamson, was born in March 1840. Within months of her birth, Lucy was stricken with an unknown illness. Stanton put aside his work to spend that summer at baby Lucy's bedside. She died in 1841, shortly after her second birthday. Their son, Edwin L. Stanton, Edwin Lamson, was born in August 1842. The boy's birth refreshed the spirits in the Stanton household after baby Lucy's death. Unlike Lucy's early years, Edwin was healthy and active. Grief, however, would return once again to the Stanton household in 1844, when Mary Stanton was left bedridden by a

In Steubenville, the Stantons welcomed two children. Their daughter, Lucy Lamson, was born in March 1840. Within months of her birth, Lucy was stricken with an unknown illness. Stanton put aside his work to spend that summer at baby Lucy's bedside. She died in 1841, shortly after her second birthday. Their son, Edwin L. Stanton, Edwin Lamson, was born in August 1842. The boy's birth refreshed the spirits in the Stanton household after baby Lucy's death. Unlike Lucy's early years, Edwin was healthy and active. Grief, however, would return once again to the Stanton household in 1844, when Mary Stanton was left bedridden by a bilious fever

Bilious fever was a medical diagnosis of fever associated with excessive bile or bilirubin in the blood stream and tissues, causing jaundice (a yellow color in the skin or sclera of the eye). The most common cause was malaria. Viral hepatitis and ...

. Never recovering, she died in March 1844. Stanton's sorrow "verged on insanity", say historians Benjamin P. Thomas and Harold M. Hyman. He had Mary's burial attire redone repeatedly, as he demanded she look just as she had when they were wed seven years prior. In the evenings, Stanton would emerge from his room with his eyes filled with tears and search the house frantically with a lamp, all the while asking, "Where is Mary?"

Stanton regrouped and began to focus on his cases by the summer. One such case was defending Caleb J. McNulty, whom Stanton had previously labelled "a glorious fellow". McNulty, a Democrat, was dismissed from his clerkship of the United States House of Representatives by unanimous vote and charged with embezzlement

Embezzlement (from Anglo-Norman, from Old French ''besillier'' ("to torment, etc."), of unknown origin) is a type of financial crime, usually involving theft of money from a business or employer. It often involves a trusted individual taking ...

when thousands of the House's money went missing. Democrats, fearing their party's disrepute, made clamorous cries for McNulty to be punished, and his conviction was viewed as a foregone conclusion. Stanton, at Tappan's request, came on as McNulty's defense. Stanton brought a motion to dismiss McNulty's indictment. He employed the use of numerous technicalities and, to the shock and applause of the courtroom, the motion was granted with all charges against McNulty dropped. As every detail of the affair was covered by newspapers around the country, Stanton's name was featured prominently nationwide.

After the McNulty scandal, Stanton and Tappan parted ways professionally. Stanton formed a partnership with one of his former students, George Wythe McCook of the "Fighting McCooks

The Fighting McCooks were members of a family of Ohioans who reached prominence as officers in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Two brothers, Daniel and John McCook, and thirteen of their sons were involved in the army, making the fam ...

". At the beginning of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

, men across the country hastened to enlist in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

, with McCook among them. Stanton might have enlisted as well, if not for his doctor's fears about his asthma. Instead, he focused on law. Stanton's practice was no longer only in Ohio, having expanded to Virginia and Pennsylvania. He concluded that Steubenville would no longer prove adequate as a headquarters, and thought Pittsburgh most appropriate for his new base. He was admitted to the bar there by late 1847.

Attorney in Pittsburgh

In Pittsburgh, Stanton formed a partnership with a prominent retired judge, Charles Shaler, while maintaining his collaboration with McCook, who had remained in Steubenville after returning from service in the Mexican–American War. Stanton argued several high-profile suits. One such proceeding was ''State of Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont Bridge Company and others'' in the

In Pittsburgh, Stanton formed a partnership with a prominent retired judge, Charles Shaler, while maintaining his collaboration with McCook, who had remained in Steubenville after returning from service in the Mexican–American War. Stanton argued several high-profile suits. One such proceeding was ''State of Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont Bridge Company and others'' in the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

. The case concerned the Wheeling Suspension Bridge, the largest suspension bridge in the world at that time, and an important connector for the National Road

The National Road (also known as the Cumberland Road) was the first major improved highway in the United States built by the federal government. Built between 1811 and 1837, the road connected the Potomac and Ohio Rivers and was a main tran ...

. The bridge's center rose some but proved to be a nuisance to passing ships with tall smokestacks. With ships unable to clear the bridge, enormous amounts of traffic, trade and commerce would be redirected to Wheeling, West Virginia

Wheeling is a city in Ohio County, West Virginia, Ohio and Marshall County, West Virginia, Marshall counties in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The county seat of Ohio County, it lies along the Ohio River in the foothills of the Appalachian Mo ...

, which at the time was still part of Virginia. On August 16, 1849, he urged the Supreme Court to enjoin Wheeling and Belmont, as the bridge was obstructing traffic into Pennsylvania, and hindering trade and commerce. Associate Justice

An associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some ...

R. C. Grier directed those who were aggrieved by the bridge's operations to go to a lower court, but left an avenue open for Stanton to file for an injunction in the Supreme Court, which he did.

Oral argument

Oral arguments are spoken presentations to a judge or appellate court by a lawyer (or parties when representing themselves) of the legal reasons why they should prevail. Oral argument at the appellate level accompanies written briefs, which also ...

s for the ''Pennsylvania v.'' ''Wheeling and Belmont'' began on February 25, 1850, which was also when Stanton was admitted to practice in the Supreme Court. Wheeling and Belmont argued that the court lacked jurisdiction over the matters concerning the case; the justices disagreed. The case proceeded, allowing Stanton to exhibit a dramatic stunt, which was widely reported on and demonstrated how the bridge was a hindrance—he had the steamer ''Hibernia'' ram its smokestack into the bridge, which destroyed it and a piece of the ship itself. May 1850 saw the case handed over to Reuben H. Walworth, the former Chancellor of New York, who returned a vivid opinion in February 1851 stating that the Wheeling Bridge was "an unwarranted and unlawful obstruction to navigation, and that it must be either removed or raised so as to permit the free and usual passage of boats." The Supreme Court concurred; in May 1852, the court ordered in a 7–2 ruling that the bridge's height be increased to . Wheeling and Belmont were unsatisfied with the ruling and asked Congress to act. To Stanton's horror, a bill declaring the Wheeling bridge permissible became law on August 31, effectively overriding the Supreme Court's ruling and authority. Stanton was disgruntled that the purpose of the court—to peacefully decide and remedy disputes between states—had been diminished by Congress.

''McCormick v. Manny''

A by-effect of Stanton's performance in ''Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont'' was that he was sought after for other prominent cases, such as the McCormick Reaper patent case of inventor

A by-effect of Stanton's performance in ''Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont'' was that he was sought after for other prominent cases, such as the McCormick Reaper patent case of inventor Cyrus McCormick

Cyrus Hall McCormick (February 15, 1809 – May 13, 1884) was an American inventor and businessman who founded the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, which became part of the International Harvester Company in 1902. Originally from the Blue ...

. In 1831, a young McCormick created a machine to harvest crops. The device was particularly useful in the burgeoning wheat fields of the Western United States. Demand for McCormick's invention grew rapidly, attracting fierce competition, especially from fellow inventor and businessman John Henry Manny. In 1854 McCormick and his two prominent lawyers, Reverdy Johnson and Edward M. Dickinson, filed suit against Manny claiming he had infringed on McCormick's patents. McCormick demanded an injunction on Manny's reaper. Manny was also defended by two esteemed lawyers, George Harding and Peter H. Watson. ''McCormick v. Manny'' was initially to be tried in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

, and the two lawyers wanted another attorney local to the city to join their team; the recommended choice was Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

. When Watson met Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Illinois. Its population was 114,394 at the 2020 United States census, which makes it the state's List of cities in Illinois, seventh-most populous cit ...

, he had a dim first impression of him, but after speaking with Lincoln, Watson saw that he might be a good choice. However, when the venue of the proceedings was transferred to Cincinnati rather than Chicago, and the necessity for Lincoln was negated, Harding and Watson went for their first choice, Edwin Stanton. Lincoln was not made aware that he had been replaced, and still appeared at the proceedings in Cincinnati with his arguments prepared. Stanton's apprehension towards Lincoln was immediate and severe, and he did well to indicate to Lincoln that he wanted him to absent himself from the case. The case proceeded with Harding, Watson and Stanton and Manny's true defenders; Lincoln did not actively participate in the planning or arguing of the case, but stayed in Cincinnati as a spectator.

Stanton's role in Manny's legal trio was as a researcher. Though he admitted that George Harding, an established patent lawyer, was more adept at the scientific aspects of the case, Stanton worked to summarize the relevant jurisprudence and case law

Case law, also used interchangeably with common law, is a law that is based on precedents, that is the judicial decisions from previous cases, rather than law based on constitutions, statutes, or regulations. Case law uses the detailed facts of ...

. To win ''McCormick v. Manny'' for Manny, Stanton, Harding and Watson had to impress upon the court that McCormick had no claim to exclusivity in his reaper's use of a divider, a mechanism on the outer end of the cutter-bar which separated the grain. A harvesting machine would not have worked properly without a divider, and Manny's defense knew this. However, to assure a win, Watson opted to use duplicity—he employed a model maker named William P. Wood to retrieve an older version of McCormick's reaper and alter it to be presented in court. Wood found a reaper in Virginia which was built in 1844, one year prior to McCormick's patent being granted. He had a blacksmith straighten the curved divider, knowing that the curved divider in Manny's reaper would not conflict with a straight one in McCormick's reaper. After using a salt and vinegar solution to add rust to where the blacksmith had worked to ensure the antiquity of the machine was undeniable, Wood sent the reaper to Cincinnati. Stanton was joyed when he examined the altered reaper, and knew the case was theirs. Arguments for the case began in September 1855. In March 1856, Justices John McLean and Thomas Drummond

Captain Thomas Drummond (10 October 1797 – 15 April 1840), from Edinburgh was a Scottish British Army officer, civil engineer and senior public official. He used the Drummond light which was employed in the trigonometrical survey of Great Br ...

delivered a ruling in favor of John Manny. McCormick appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, and ''McCormick v. Manny'', was, all of a sudden, a political issue, and the matters concerning the case found their way to the floor of Congress. Stanton would later appoint Wood to be superintendent of the military prisons of the District of Columbia during the Civil War.

Second marriage

In February 1856 Stanton became engaged to Ellen Hutchinson, sixteen years Stanton's junior. She came from a prominent family in the city; her father was Lewis Hutchinson, a wealthy merchant and warehouseman and a descendant ofMeriwether Lewis

Meriwether Lewis (August 18, 1774 – October 11, 1809) was an American explorer, soldier, politician, and public administrator, best known for his role as the leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, with ...

. They were married on June 25, 1856, at Hutchinson's father's home. Stanton moved to Washington where Stanton expected important work with the Supreme Court.

Emergence in Washington

In Pennsylvania, Stanton had become intimately acquainted with Jeremiah S. Black, the chief judge in the state'ssupreme court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

. This friendship proved profitable for Stanton when in March 1857, the recently inaugurated fifteenth president, James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

, made Black his Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

. Black's accession to his new post was soon met with a land claims issue in California. In the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo officially ended the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). It was signed on 2 February 1848 in the town of Villa de Guadalupe, Mexico City, Guadalupe Hidalgo.

After the defeat of its army and the fall of the cap ...

that ended the Mexican–American War and gave California to the United States, the United States agreed to recognize valid land grants by Mexican authorities. This was followed by the California Land Claims Act of 1851, which established a board to review claims to California lands. One such claim was made by Joseph Yves Limantour, a French-born merchant who asserted ownership of an assemblage of lands that included important sections of the state, such as a sizeable part of San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

. When his claims were recognized by the land commissioners, the U.S. government appealed. Meanwhile, Black corresponded with a person named Auguste Jouan, who stated that Limantour's claims were invalid, and that he, under Limantour's employ, forged the date listed on one of the approved grants. Black needed an individual loyal to the Democratic Party and to the Buchanan administration, who could faithfully represent the administration's interests in California; he chose Stanton.

Ellen Stanton loathed the idea. In California Edwin would be thousands of miles away from her for what was sure to be months, leaving her lonely in Washington, where she had few friends. Moreover, on May 9, 1857, Ellen had a daughter whom the Stantons named Eleanor Adams. After the girl's delivery, Ellen fell ill, which frightened Edwin and delayed his decision to go to California. In October 1857 Stanton finally agreed to represent the Buchanan administration's interests in California. Having agreed to a compensation of $25,000, (~$ in ) Stanton set sail from New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

on February 19, 1858, aboard the '' Star of the West'', along with his son Eddie, James Buchanan Jr., the president's nephew, and Lieutenant H. N. Harrison, who was assigned to Stanton's detail by the Navy. After a tempestuous voyage, the company docked in Kingston, Jamaica

Kingston is the Capital (political), capital and largest city of Jamaica, located on the southeastern coast of the island. It faces a natural harbour protected by the Palisadoes, a long spit (landform), sand spit which connects the town of Por ...

, where slavery was disallowed. On the island, the climate pleased Stanton greatly, and at a church there, Stanton was surprised to see blacks and whites sitting together. Afterwards, Stanton and his entourage landed in Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

, and left there on a ship three times larger than the one on which they came, the ''Sonora''. On March 19 the company finally docked in San Francisco, and bunkered at the International Hotel.

Stanton took to his work with haste. In aid of his case Stanton, along with his entire party and two clerks, went about arranging disordered records from California's time under Mexico. The "Jemino Index" that he uncovered gave information on land grants up to 1844, and with the assistance of a Congressional act, Stanton unearthed records from all over the state pertaining to Mexican grants. Stanton and company worked for months sorting the land archives; meanwhile, Stanton's arrival in California produced gossip and scorn from locals, especially from those whose land claims would be in jeopardy should Stanton's work prove victorious. Further, President Buchanan and Senator Douglas were wrestling for control of California, and Stanton was caught in the crosshairs, resulting in a defamatory campaign against Stanton by Douglas' supporters. The campaign disheartened Stanton, but barely distracted him.

Limantour had built up a speciously substantial case. He had accrued a preponderance of ostensibly sound evidence, such as witness testimony, grants signed by Manuel Micheltorena

Joseph Manuel María Joaquin Micheltorena y Llano (8 June 1804 – 7 September 1853) was a brigadier general and adjutant-general of the Mexican Army, List_of_governors_of_California_before_1850#Mexican_governors_of_California_(1837–47), gover ...

, the Mexican governor of California prior to cessation, and paper with a special Mexican government stamp. However, Auguste Jouan's information was instrumental in Stanton's case. According to Jouan, Limantour had received dozens of blank documents signed by Governor Micheltorena, which Limantour could fill in as he willed. Further, Jouan had borne a hole in one of the papers to erase something, a hole that was still present in the document. Stanton also acquired letters that explicitly laid out the fraud, and stamps used by customs officials, one authentic and the other fraudulent. The fraudulent one had been used eleven times, all on Limantour's documents. When Stanton sent to the Minister of the Exterior in Mexico City, they could not locate records corroborating Limantour's grants. In late 1858 Limantour's claims were denied by the land commission, and he was arrested on perjury charges. He posted a $35,000 bail and left the country.

As 1858 drew to a close, and Stanton prepared to return home, Eddie became sick. Whenever Stanton made arrangements to leave California, his son's condition grew worse. Edwin had written Ellen as often as he could as her anxiety and loneliness increased in Washington. She criticized him for leaving her in the town alone with young "Ellie". January 3, 1859, saw Stanton and company leave San Francisco. He was home in early February. In the nation's capital Stanton advised President Buchanan on patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

, and helped Attorney General Black extensively, even being mistaken as an Assistant Attorney General. Nonetheless, Stanton's affairs in Washington paled in comparison to the excitement he had experienced on the other side of the country—at least until he found himself defending a man who had become fodder for sensationalists and gossipers around the country.

Daniel Sickles trial

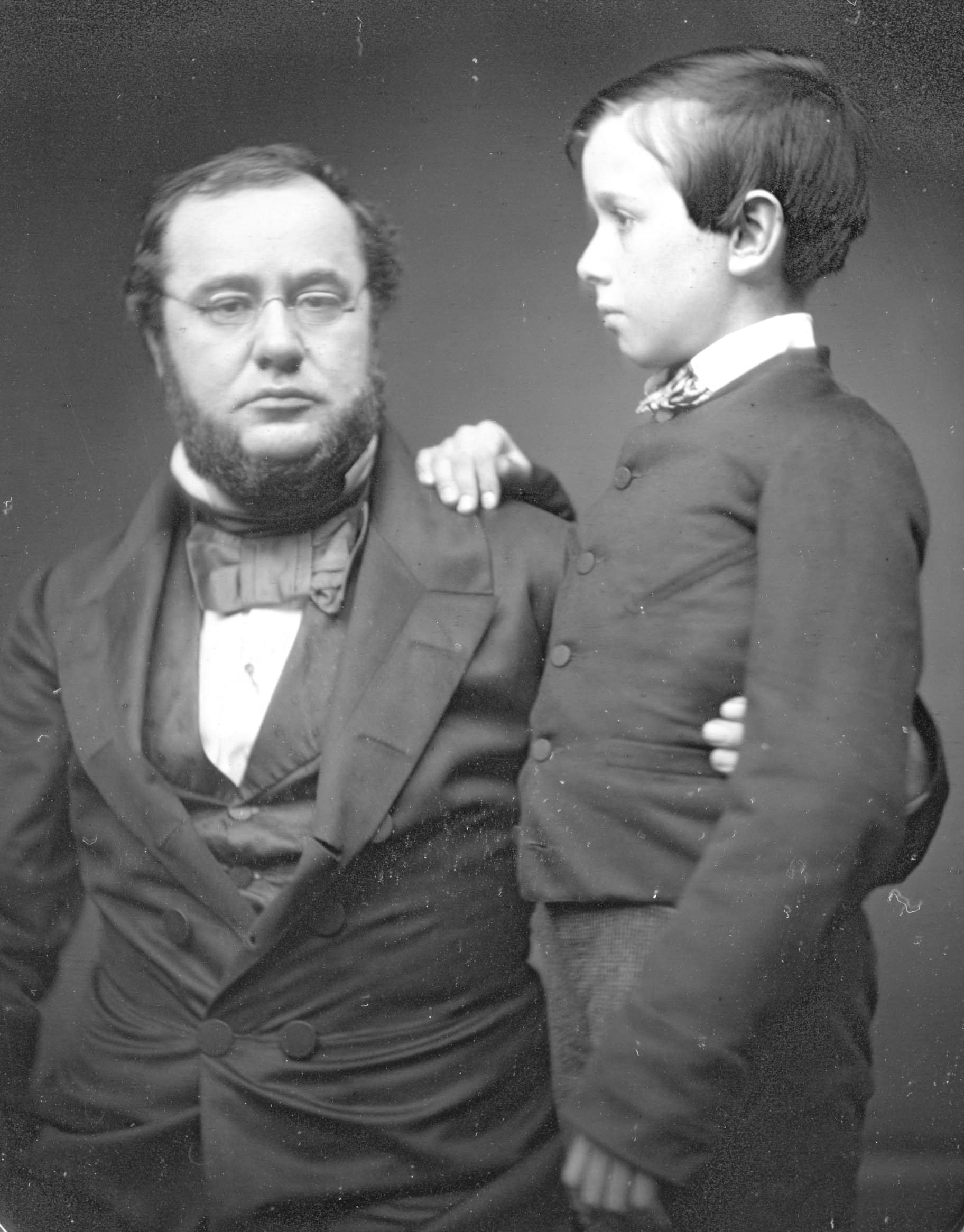

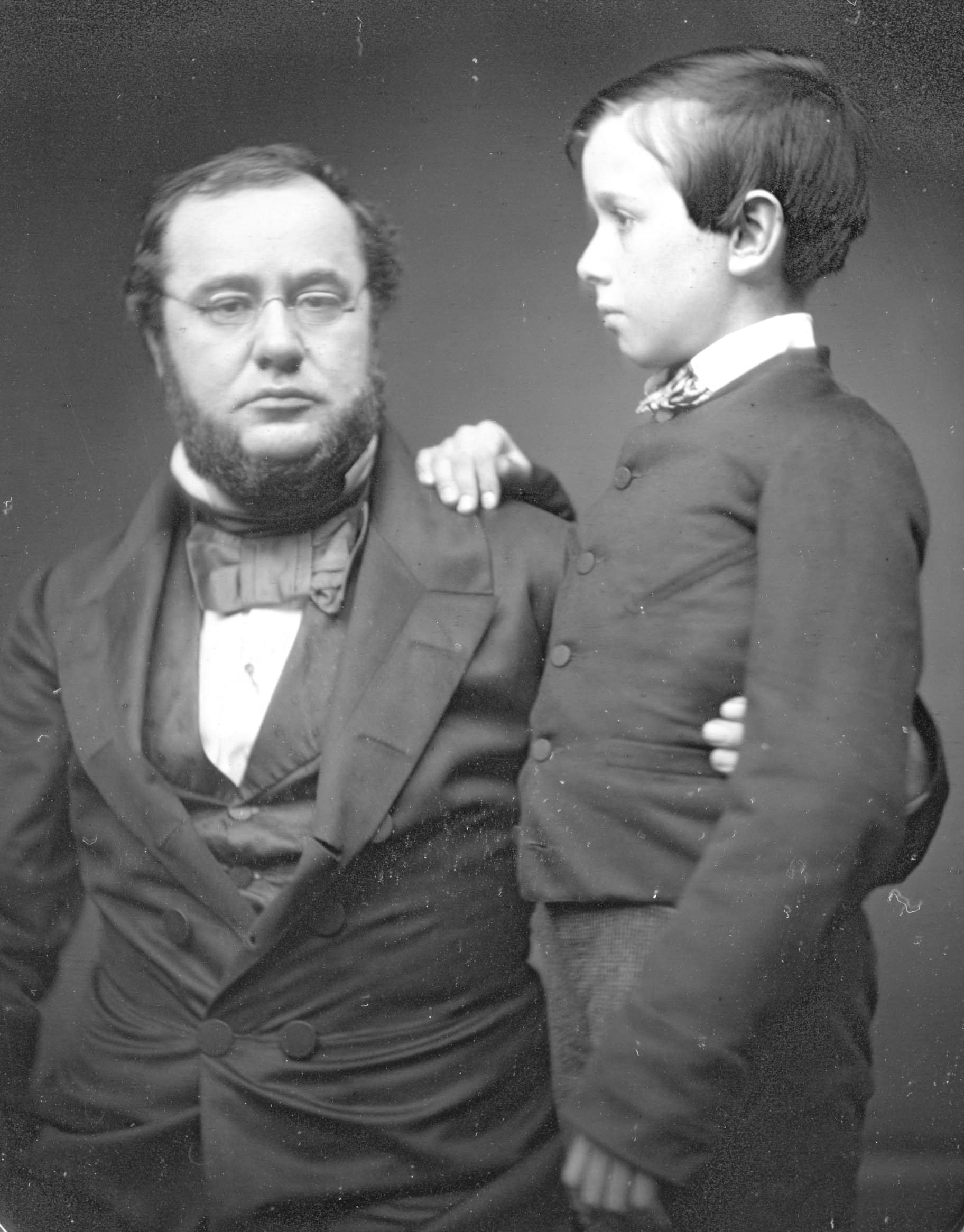

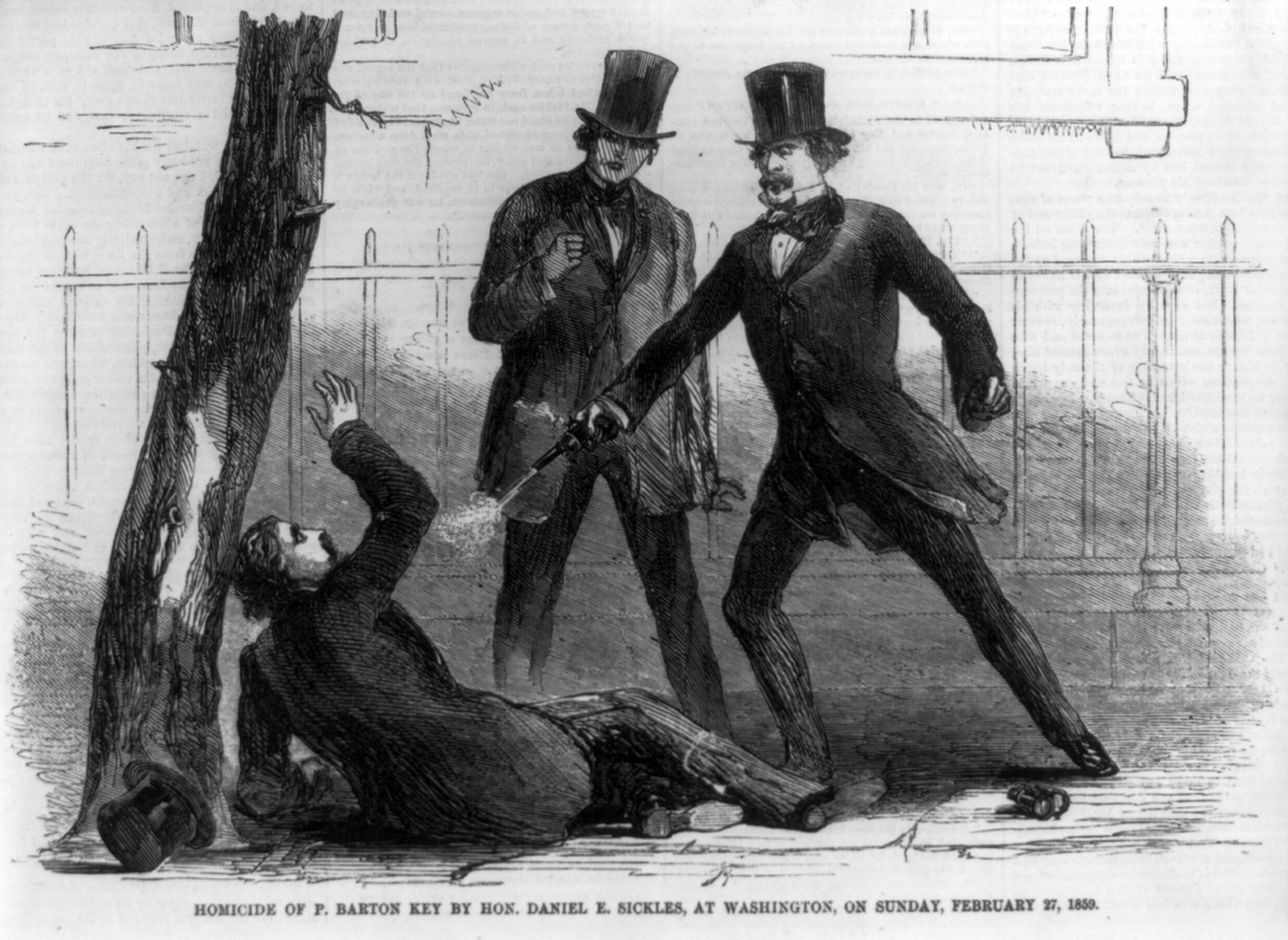

Daniel Sickles

Daniel Edgar Sickles (October 20, 1819May 3, 1914) was an American politician, American Civil War , Civil War veteran, and diplomat. He served in the United States House of Representatives , U.S. House of Representatives both before and after t ...

was a member of the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

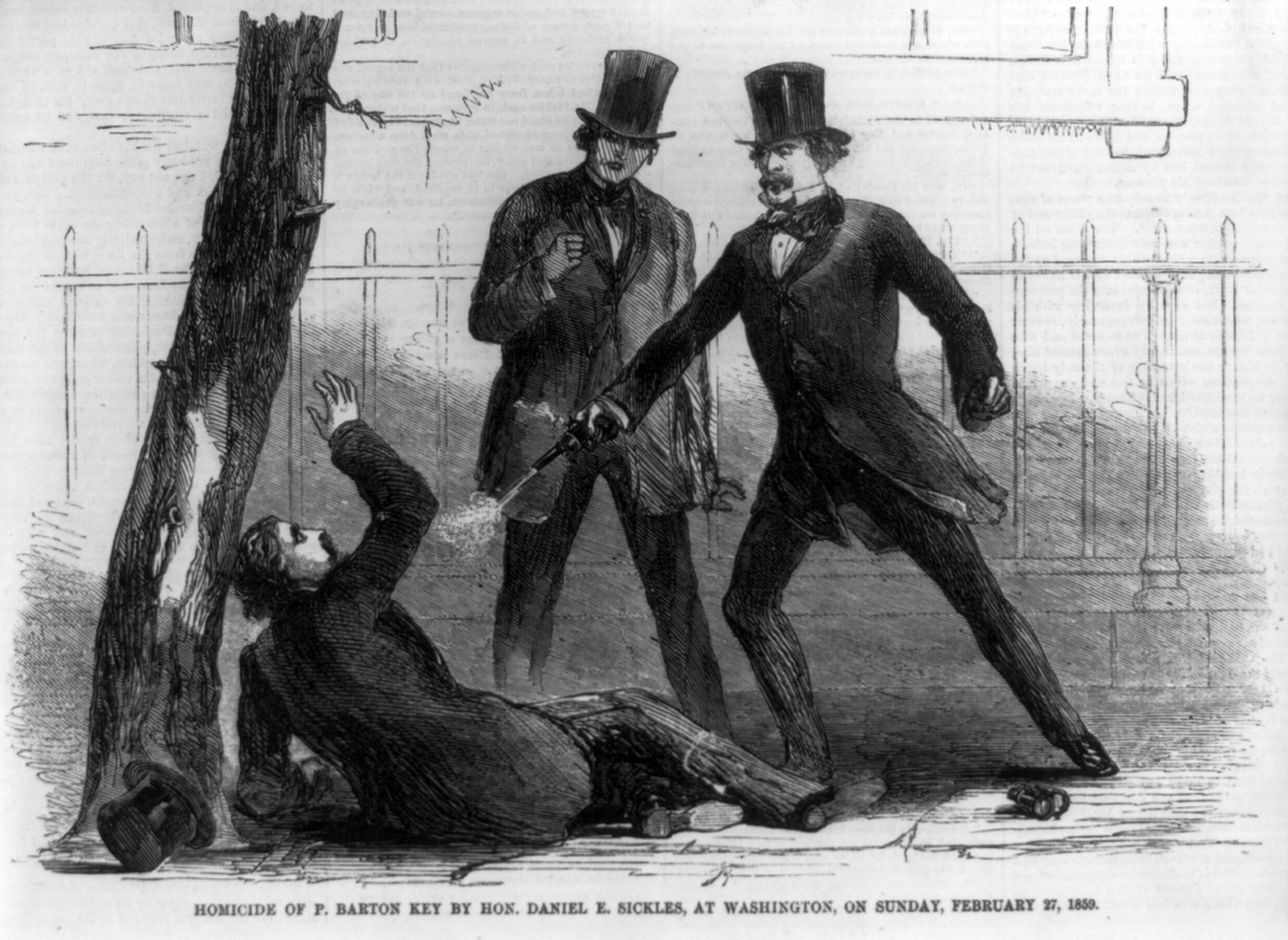

from New York. He was married to Teresa Bagioli Sickles, the daughter of composer Antonio Bagioli. Sickles' wife had begun an affair

An affair is a relationship typically between two people, one or both of whom are either married or in a long-term Monogamy, monogamous or emotionally-exclusive relationship with someone else. The affair can be solely sexual, solely physical or ...

with Philip Barton Key, the United States attorney for the District of Columbia

The United States attorney for the District of Columbia (USADC) is responsible for representing the Federal government of the United States, federal government in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. The U.S. Attorney's ...

and the son of Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key (August 1, 1779January 11, 1843) was an American lawyer, author, and poet from Frederick, Maryland, best known as the author of the poem "Defence of Fort M'Henry" which was set to a popular British tune and eventually became t ...

, writer of ''The Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written by American lawyer Francis Scott Key on September 14, 1814, after he witnessed the bombardment of Fort ...

''. On Sunday, February 27, 1859, Sickles confronted Key in Lafayette Square, declaring, "Key, you scoundrel, you have dishonored my home; you must die", then shot Key to death. Sickles then went to the home of Attorney General Black and admitted his crime. The subsequent Thursday he was charged with murder by a grand jury

A grand jury is a jury empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a person to testify. A grand ju ...

. The Sickles affair gained nationwide media attention for both its scandalous nature and its proximity to the White House. Soon, the press speculated that Daniel Sickles' political esteem was on the account of an affair between his wife and President Buchanan. Prominent criminal lawyer James T. Brady and his partner, John Graham, came to Sickles' defense, and solicited Stanton to join their team.

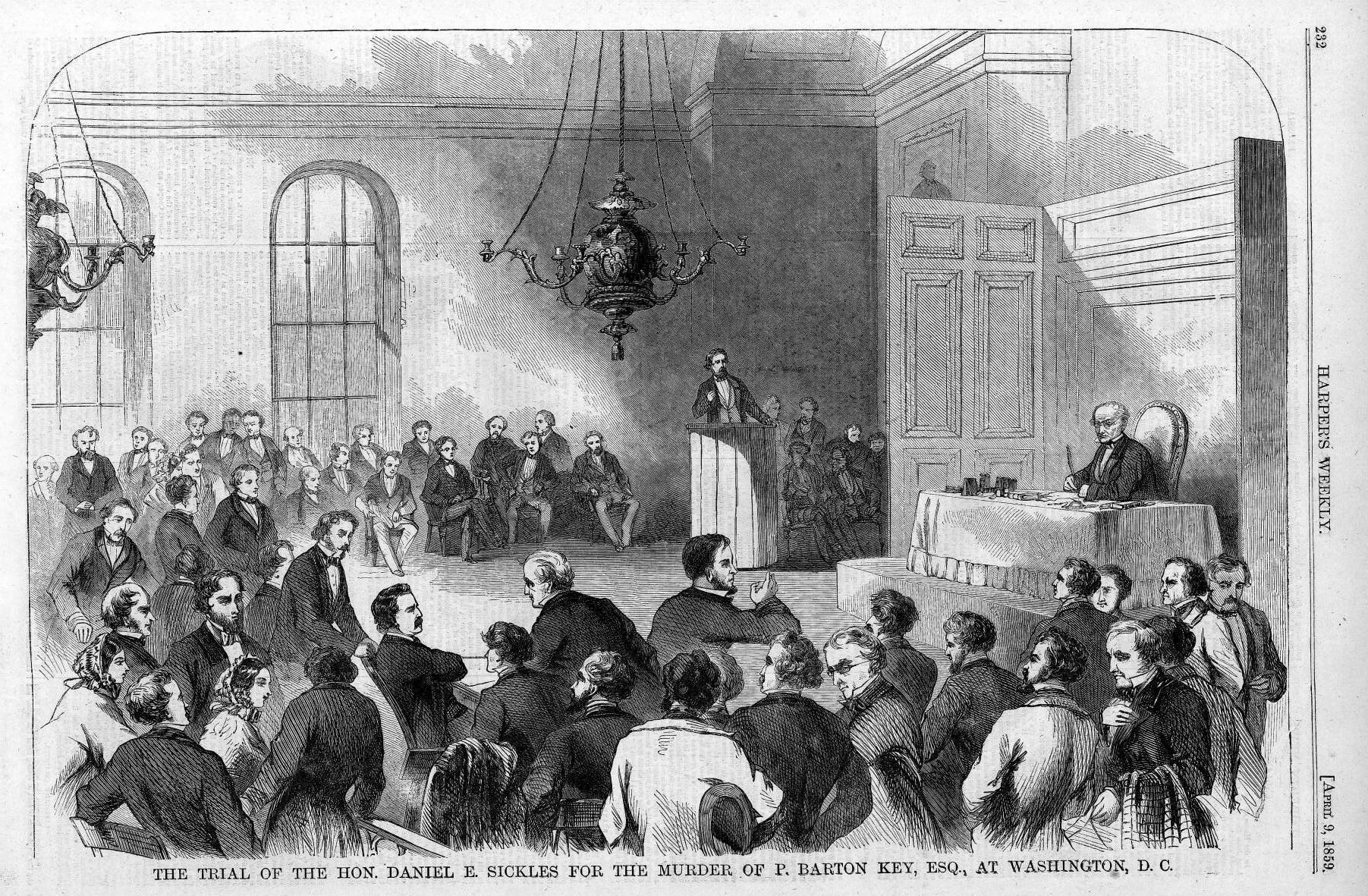

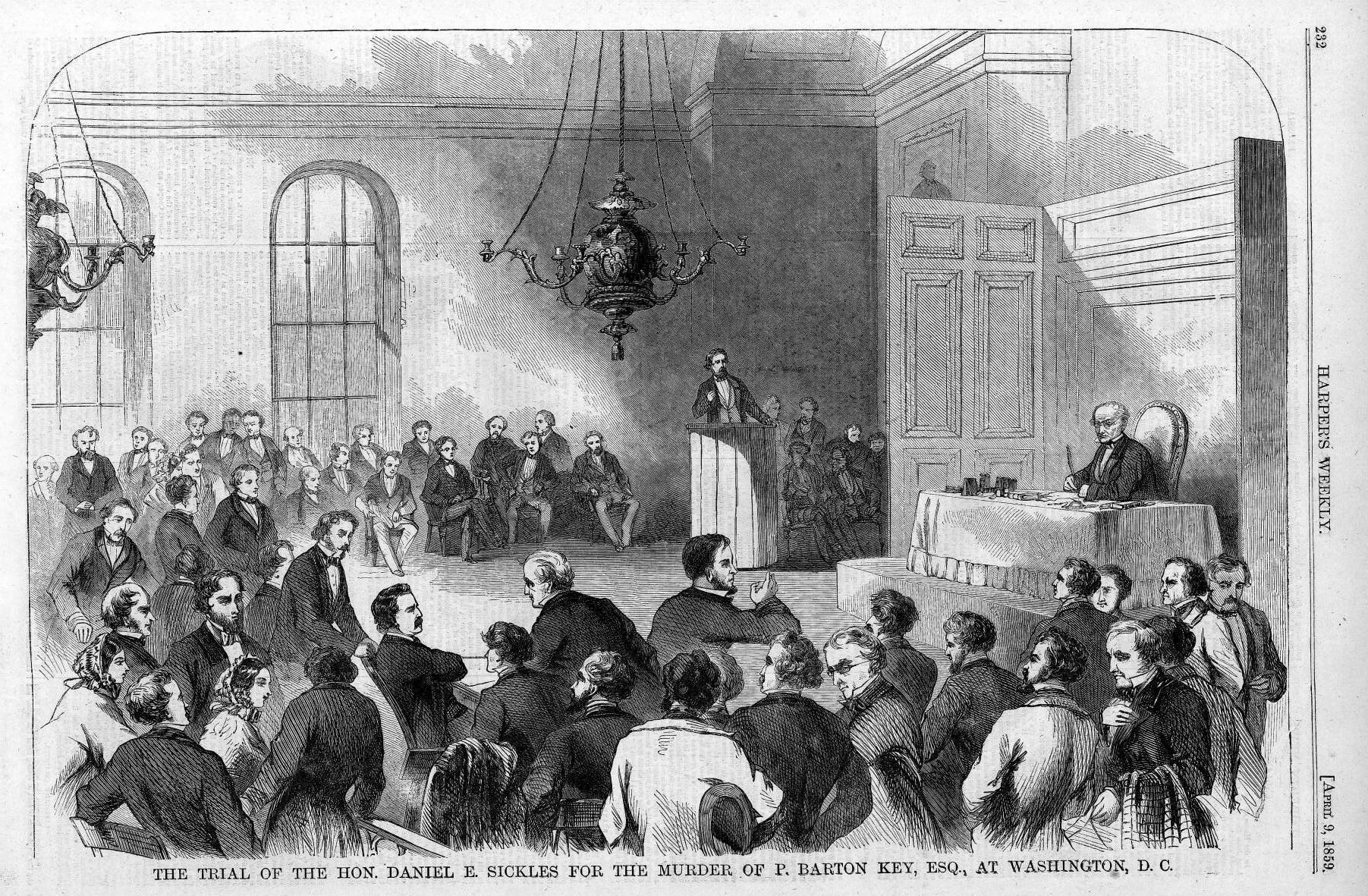

Arguments for the trial began on April 4. The prosecution wanted to advance the theory that Sickles had also committed adultery and did not pay very much mind to his wife or her activities. When the judge disallowed this, the prosecution opted instead to highlight the heinous nature of Sickles' murder, and not address his reasons for doing the crime. Sickles' defense countered that Sickles had suffered from a temporary bout of insanity, the first successful such instance of an insanity plea in American jurisprudence. The events in the courtroom during the trial were nothing if not dramatic. When Stanton delivered closing arguments, stating that marriage is sacred and that a man should have the right to defend his marriage against those who chose to defile the purity of the sacrament, the courtroom erupted in cheers. A law student described Stanton's argument during the trial, "a typical piece of Victorian rhetoric, an ingenious thesaurus of aphorisms on the sanctity of the family." The jury in the case deliberated for just over an hour before declaring Sickles not guilty. The judge ordered that Sickles be released from his arrest. Outside the courthouse, Sickles, Stanton and company met a throng of individuals in adulation of the victory.

Arguments for the trial began on April 4. The prosecution wanted to advance the theory that Sickles had also committed adultery and did not pay very much mind to his wife or her activities. When the judge disallowed this, the prosecution opted instead to highlight the heinous nature of Sickles' murder, and not address his reasons for doing the crime. Sickles' defense countered that Sickles had suffered from a temporary bout of insanity, the first successful such instance of an insanity plea in American jurisprudence. The events in the courtroom during the trial were nothing if not dramatic. When Stanton delivered closing arguments, stating that marriage is sacred and that a man should have the right to defend his marriage against those who chose to defile the purity of the sacrament, the courtroom erupted in cheers. A law student described Stanton's argument during the trial, "a typical piece of Victorian rhetoric, an ingenious thesaurus of aphorisms on the sanctity of the family." The jury in the case deliberated for just over an hour before declaring Sickles not guilty. The judge ordered that Sickles be released from his arrest. Outside the courthouse, Sickles, Stanton and company met a throng of individuals in adulation of the victory.

Early work in politics (1860–1862)

During the1860 United States presidential election

Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 6, 1860. The Republican Party ticket of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin emerged victorious in a four-way race. With an electoral majority composed only of Northern states ...

Stanton supported Vice President John C. Breckinridge, due to his work with the Buchanan administration and his belief that only a win by Breckinridge would keep the country together. Privately he predicted that Lincoln would win.

In Buchanan's cabinet

In late 1860, President Buchanan was formulating his yearlyState of the Union

The State of the Union Address (sometimes abbreviated to SOTU) is an annual message delivered by the president of the United States to a Joint session of the United States Congress, joint session of the United States Congress near the beginning ...

address to Congress, and asked Attorney General Black to offer insight into the legality and constitutionality of secession. Black then asked Stanton for advice. Stanton approved a strongly worded draft of Black's response to Buchanan, which denounced secession from the Union as illegal. Buchanan gave his address to Congress on December 3. Meanwhile, Buchanan's cabinet were growing more discontent with his handling of secession, and several members deemed him too weak on the issue. On December 5th, his secretary of the treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

, Howell Cobb resigned. On December 9th, Secretary of State Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was a United States Army officer and politician. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He was also the 1 ...

, disgruntled over Buchanan's failure to defend the government's interests in the South, tendered his resignation. Black was nominated to replace Cass on December 12. About a week later, Stanton, at the time in Cincinnati, was told to come to Washington at once, for he had been confirmed by the Senate as Buchanan's new Attorney General. He was sworn in on December 20th.

Stanton met a cabinet in disarray over the issue of secession. Buchanan did not want to agitate the South any further, and sympathized with the South's cause. On December 9th, Buchanan had agreed with South Carolinian congressmen that the military installations in the state would not be reinforced unless force against them was perpetrated. However, on the day that Stanton assumed his position, Maj. Robert Anderson moved his unit to Fort Sumter, South Carolina, which the Southerners viewed as Buchanan reneging on his promise. South Carolina issued an ordinance of secession

An Ordinance of Secession was the name given to multiple resolutions drafted and ratified in 1860 and 1861, at or near the beginning of the American Civil War, by which each seceding slave-holding Southern state or territory formally Secession in ...

soon after, declaring itself independent of the United States. The South Carolinians demanded that federal forces leave Charleston Harbor altogether; they threatened carnage if they did not get compliance. The following day, Buchanan gave his cabinet a draft of his response to the South Carolinians. Secretaries Thompson and Philip Francis Thomas, of the Treasury Department, thought the president's response too pugnacious; Stanton, Black and Postmaster General Joseph Holt

Joseph Holt (January 6, 1807 – August 1, 1894) was an American lawyer, soldier, and politician. As a leading member of the James Buchanan#Administration and Cabinet, Buchanan administration, he succeeded in convincing Buchanan to oppose the ...

thought it too placatory. Isaac Toucey, Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

, was alone in his support of the response.

Stanton was unnerved by Buchanan's ambivalence towards the South Carolina secession crisis, and wanted to stiffen him against complying to the South's demands. On December 30th, Black came to Stanton's home, and the two agreed to pen their objections to Buchanan ordering a withdrawal from Fort Sumter. If he did such a thing, the two men, along with Postmaster General Holt, agreed that they would resign, delivering a crippling blow to the administration. Buchanan obliged them. The South Carolinian delegates got their response from President Buchanan on New Year's Eve 1860; the president would not withdraw forces from Charleston Harbor.

By February 1st, six Southern states had followed South Carolina's lead and passed ordinances of secession

Ordinance may refer to:

Law

* Ordinance (Belgium), a law adopted by the Brussels Parliament or the Common Community Commission

* Ordinance (India), a temporary law promulgated by the President of India on recommendation of the Union Cabinet

* Em ...

, declaring themselves to no longer be a part of the United States. On February 18th, Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

was sworn in as the President of the Confederate States

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the unrecognized breakaway Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and commander-in-chief of the Confederate A ...

. Meanwhile, Washington was astir with talk of coups and conspiracies. Stanton thought that discord would ravage the capital on February 13, when electoral votes were being counted; nothing happened. Again, Stanton thought, when Lincoln was sworn in on March 4th there would be violence; this did not come to pass. Lincoln's inauguration did give Stanton a flickering of hope that his efforts to keep Fort Sumter defended would not be in vain, and that Southern aggression would be met with force in the North. In his inauguration speech, Lincoln did not say he would outlaw slavery throughout the nation, but he did say that he would not support secession in any form, and that any attempt to leave the Union was not lawful. In Stanton, Lincoln's words were met with cautious optimism. The new president submitted his choices for his cabinet on March 5, and by that day's end, Stanton was no longer the attorney general. He lingered in his office for a while to help settle in and guide his replacement, Edward Bates.

Cameron's advisor

On July 21st, the North and the South experienced their first major clash at Manassas Junction in Virginia, the

On July 21st, the North and the South experienced their first major clash at Manassas Junction in Virginia, the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run, called the Battle of First Manassas

. by Confederate States ...

. Northerners thought the battle would end the war, and defeat the Confederacy decisively; however, the bloody encounter ended with the Union Army retreating to Washington. Lincoln wanted to bolster Northern numbers afterwards, with many in the North believing the war would be more arduous than they initially expected, but when more than 250,000 men signed up, the federal government did not have enough supplies for them. The War Department had states buy the supplies, assuring them that they would be reimbursed. This led to states selling the federal government items that were usually damaged or worthless at very high prices. Nonetheless, the government bought them.

Soon, . by Confederate States ...

Simon Cameron

Simon Cameron (March 8, 1799June 26, 1889) was an American businessman and politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate and served as United States Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln at the start of the Ameri ...

, Lincoln's Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, was being accused of incompetently handling his department, and some wanted him to resign. Cameron sought out Stanton to advise him on legal matters concerning the War Department's acquisitions, among other things. Calls for Cameron to resign grew louder when he endorsed a bombastic November 1861 speech given by Col. John Cochrane to his unit. " should take the slave by the hand, placing a musket in it, and bid him in God's name strike for the liberty of the human race", Cochrane said. Cameron embraced Cochrane's sentiment that slaves should be armed, but it was met with repudiation in Lincoln's cabinet. Caleb B. Smith, the Secretary in the Department of the Interior, scolded Cameron for his support of Cochrane.

Cameron inserted a call to arm the slaves in his report to Congress, which would be sent along with Lincoln's address to the legislature. Cameron gave the report to Stanton, who amended it with a passage that went even further in demanding that slaves be armed, stating that those who rebel against the government lose their claims to any type of property, including slaves, and that it was "clearly the right of the Government to arm slaves when it may become necessary as it is to use gunpowder or guns taken from the enemy". Cameron gave the report to Lincoln, and sent several copies to Congress and the press. Lincoln wanted the portions containing calls to arm the slaves removed, and ordered the transmission of Cameron's report be stopped and replaced with an altered version. Congress received the version without the call to arm slaves, while the press received a version with it. When newspapers published the document in its entirety, Lincoln was excoriated by Republicans, who thought him weak on the issue of slavery, and disliked that he wanted the plea to arm slaves removed.

The president resolved to dismiss Cameron when abolitionists in the North settled over the controversy. Cameron would not resign until he was sure of his successor, and that he could leave the cabinet without damaging his reputation. When a vacancy in the post of Minister to Russia presented itself, Cameron and Lincoln agreed that he would fill the post when he resigned. As for a successor, Lincoln thought Joseph Holt best for the job, but his secretary of state, William H. Seward, wanted Stanton to succeed Cameron. Salmon Chase, Stanton's friend and Lincoln's Treasury Secretary, agreed. Stanton had been preparing for a partnership with Samuel L. M. Barlow in New York, but abandoned these plans when he heard of his possible nomination. Lincoln nominated Stanton to the post of Secretary of War on January 13. He was confirmed two days following.

Lincoln's secretary of war (1862–1865)

Early days in office

Under Cameron, the War Department had earned the moniker "the lunatic asylum." The department was barely respected among soldiers or government officials, and its authority was routinely disregarded. The army's generals held the brunt of the operating authority in the military, while the President and the War Department interceded only in exceptional circumstances. The department also had strained relations with Congress, especially Representative John Fox Potter, head of the House's "Committee on Loyalty of Federal employees", which sought to root out Confederate sympathizers in the government. Potter had prodded Cameron to remove about fifty individuals he suspected of Confederate sympathies; Cameron had paid him no mind. Stanton was sworn in on January 20. Immediately, he set about repairing the fractious relationship between Congress and the War Department. Stanton met with Potter on his first day as secretary, and on the same day, dismissed four persons whom Potter deemed unsavory. This was well short of the fifty people Potter wanted gone from the department, but he was nonetheless pleased. Stanton also met with Senator Benjamin Wade and his Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. The committee was a necessary and fruitful ally; it hadsubpoena

A subpoena (; also subpœna, supenna or subpena) or witness summons is a writ issued by a government agency, most often a court, to compel testimony by a witness or production of evidence under a penalty for failure. There are two common types of ...

power, thus allowing it to acquire information Stanton could not, and could help Stanton remove War Department staffers. Wade and his committee were happy to find an ally in the executive branch

The executive branch is the part of government which executes or enforces the law.

Function

The scope of executive power varies greatly depending on the political context in which it emerges, and it can change over time in a given country. In ...

, and met with Stanton often thereafter. Stanton made a number of organizational changes within the department as well. He appointed John Tucker, an executive at the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad

The Reading Company ( ) was a Philadelphia-headquartered railroad that provided passenger and freight transport in eastern Pennsylvania and neighboring states from 1924 until its acquisition by Conrail in 1976.

Commonly called the Reading Railro ...

, and Peter H. Watson, his partner in the reaper case, to be his assistant secretaries, and had the staff at the department expanded by over sixty employees. Further, Stanton appealed to the Senate to cease appointments of military officials until he could review the more than 1,400 individuals up for promotion. Hitherto, military promotions were a spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a rewar ...

, where individuals favorable to the administration were given promotions, regardless of merit. This ceased under Stanton.

On January 29 Stanton ordered that all contracts to manufacturers of military materials and supplies outside the United States be voided and replaced with contracts within the country, and that no such further contracts be made with foreign companies. The order provoked apprehension in Lincoln's cabinet. The United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

were searching for cause to recognize and support the Confederates, and Stanton's order may have given it to them. Secretary of State Seward thought the order would "complicate the foreign situation." Stanton persisted, and his January 29 order stood.

Meanwhile, Stanton worked to create an effective transportation and communication network across the North. His efforts focused on the railroad system and the telegraph line

Electrical telegraphy is point-to-point distance communicating via sending electric signals over wire, a system primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most wide ...

s. Stanton worked with Senator Wade to push through Congress a bill that would codify the ability of the president and his administration to forcibly seize railroad and telegraph lines for their purposes. Railroad companies in the North were accommodating to the needs and desires of the federal government for the most part, and the law was rarely used. Stanton also secured the government's use of telegraph. He relocated the military's telegraphing operations from McClellan's army headquarters to his department, a decision the general was none too pleased with. The relocation gave Stanton closer control over the military's communications operations, and he exploited this. Stanton forced all members of the press to work through Assistant Secretary Watson, where unwanted journalists would be disallowed access to official government correspondence. If a member of the press went elsewhere in the department, they would be charged with espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

.

Prior to Stanton's incumbency as War Secretary, President Lincoln apportioned responsibility for the security of government against treachery and other unsavory activities to several members of his cabinet, mostly Secretary Seward, as he did not trust Attorney General Bates or Secretary Cameron. Under Secretary Stanton, the War Department would have consolidated responsibility for internal security. A lynchpin of Seward's strategy to maintain internal security was the use of arbitrary arrests and detentions, and Stanton continued this practice. Democrats harshly criticized the use of arbitrary arrests, but Lincoln contended that it was his primary responsibility to maintain the integrity and security of the government, and that waiting until possible betrayers committed guilty acts would hurt the government. At Stanton's behest, Seward continued the detention of only the most risky inmates, and released all others.

General-in-Chief

Lincoln eventually grew tired of McClellan's inaction, especially after his January 27, 1862, order to advance against the Confederates in the Eastern Theatre had provoked little military response from McClellan. On March 11, Lincoln relieved McClellan of his position as general-in-chief of the whole Union army—leaving him in charge of only the Army of the Potomac—and replaced him with Stanton. This created a bitter chasm in the relationship between Stanton and McClellan, and led McClellan's supporters to claim that Stanton "usurped" the role of general-in-chief, and that a secretary of war should be subordinate to military commanders. Lincoln ignored such calls, leaving military power consolidated with himself and Stanton. Meanwhile, McClellan was preparing for the first major military operation in the Eastern Theatre, thePeninsula Campaign

The Peninsula campaign (also known as the Peninsular campaign) of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March to July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The oper ...

. The Army of the Potomac began its movement to the Virginia Peninsula on March 17. The first action of the campaign was at Yorktown. Lincoln wanted McClellan to attack the town outright, but McClellan's inspection of the Confederate defensive works there compelled him to lay siege to the town instead. Washington politicians were angered at McClellan's choice to delay an attack. McClellan, however, requested reinforcements for his siege—the 11,000 men in Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin's division, of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was an American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command of the ...

's corps. Stanton wanted Maj. Gen. McDowell's corps to stay together and march on to Richmond, but McClellan persisted, and Stanton eventually capitulated.

McClellan's campaign lasted several months. However, after Gen. Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

became the commander of local Confederate forces on June 1, he launched a series of offensives against the Army of the Potomac, which, by late June 1862, was just a few miles from the Confederate capital, Richmond. In addition, Stanton ordered McClellan to transfer one of his corps east to defend Washington. McClellan and the Army of the Potomac were pushed back to Harrison's Landing in Virginia, where they were protected by Union gunboats. In Washington, Stanton was blamed for McClellan's defeat by the press and the public. On April 3 Stanton had suspended military recruiting efforts under the mistaken impression that McClellan's Peninsula Campaign would end the war. With McClellan retreating and the casualties from the campaign piling up, the need for more men rose significantly. Stanton restored recruiting operations on July 6, when McClellan's defeat on the Peninsula was firmly established, but the damage was done. The press, angered by Stanton's strict measures regarding journalistic correspondence, unleashed torrents of scorn on him, furthering the narrative that he was the only encumbrance to McClellan's victory.

The attacks hurt Stanton, and he considered resigning, but he remained in his position, at Lincoln's request. As defeats piled up, Lincoln sought to give some order to the disparate divisions of Union forces in Virginia. He decided to consolidate the commands of Maj. Gens. McDowell, John C. Frémont

Major general (United States), Major-General John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was a United States Army officer, explorer, and politician. He was a United States senator from California and was the first History of the Repub ...

, and Nathaniel P. Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union Army, Union general during the American Civil War, Civil War. A millworker, Banks became prominent in local ...

into the Army of Virginia, which was to be commanded by Maj. Gen. John Pope who was brought east after success in the West. Lincoln was also convinced that the North's army needed reformation at the highest ranks; he and Stanton being the ''de facto'' commanders of Union forces had proved too much to bear, so Lincoln would need a skilled commander. He chose Gen. Henry W. Halleck. Halleck arrived in Washington on July 22, and was confirmed as the general-in-chief of Union forces the following day.

War rages on

In the final days of August 1862, Gen. Lee scourged Union forces, routing them at Manassas Junction in the

In the final days of August 1862, Gen. Lee scourged Union forces, routing them at Manassas Junction in the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

, this time, against Maj. Gen. Pope and his Army of Virginia. A number of people, including Maj. Gen. Halleck and Secretary Stanton, thought Lee would turn his attention to Washington. Instead, Lee began the Maryland Campaign

The Maryland campaign (or Antietam campaign) occurred September 4–20, 1862, during the American Civil War. The campaign was Confederate States Army, Confederate General (CSA), General Robert E. Lee's first invasion of the Northern United Stat ...

. The campaign started with a skirmish at Mile Hill on September 4, followed by a major confrontation at Harpers Ferry. Lincoln, without consulting Stanton, perhaps knowing Stanton would object, merged Pope's Army of Virginia into McClellan's Army of the Potomac. With 90,000 men, McClellan launched his army into the bloody Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam ( ), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virgi ...

, and emerged victorious, pushing the Army of Northern Virginia back into Virginia, and effectively ending Lee's Maryland offensive. McClellan's success at Antietam Creek

Antietam Creek () is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed August 15, 2011 tributary of the Potomac River located in south central Pennsylvania and western Maryland in the ...

emboldened him to demand that Lincoln and his government cease obstructing his plans, Halleck and Stanton be removed, and he be made general-in-chief of the Union Army. Meanwhile, he refused to move aggressively against Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia, which was withdrawing towards Richmond. McClellan's unreasonable requests continued, as did his indolence, and Lincoln's patience with him soon grew thin. Lincoln dismissed him from leadership of the Army of the Potomac on November 5. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everts Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the American Civil War and a three-time Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successfu ...

replaced McClellan days later.