Edward Wilmot Blyden on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward Wilmot Blyden (3 August 1832 – 7 February 1912) was an

''Edward Wilmot Blyden: Pan-Negro Patriot, 1832–1912''

New York: Oxford University Press, 1967, p. 4. Blyden and his family lived near the church, and Knox was impressed with the studious, intelligent boy. Knox became his mentor, encouraging Blyden's considerable aptitude for oratory and literature. Mainly because of his close association with Knox, the young Blyden decided to become a minister, which his parents encouraged. In May 1850, Blyden, accompanied by Reverend Knox's wife, went to the United States to enroll in

Blyden married Sarah Yates, an

Blyden married Sarah Yates, an

edited by Yvonne Chireau, Nathaniel Deutsch; Oxford University Press, 1999, Google eBook, p. 15. In their book ''Israel in the Black American Perspective'', Robert G. Weisbord and Richard Kazarian write that in his booklet ''The Jewish Question'' (published in 1898, the year after the First Zionist Congress) Blyden describes that while travelling in the Middle East in 1866 he wanted to travel to "the original home of the Jews–to see Jerusalem and Mt. Zion, the joy of the whole earth". While in Jerusalem he visited the Western Wall. Blyden advocated for the Jewish settlement of Palestine and chided Jews for not taking advantage of the opportunity to live in their ancient homeland. Blyden was familiar with

"The Colors of Zion: Black, Jewish, and Irish Nationalisms at the turn of the Century"

''Modernism/modernity'' 12.3 (2005), Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 369–84.

Call of Providence to the Descendants of Africa in America", A Discourse Delivered to Coloured Congregations in the Cities of New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Harrisburg, during the Summer of 1862, in ''Liberia's Offering: Being Addresses, Sermons, etc.''

New York: John A. Gray, 1862.

''Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race''

London, W. B. Whittingham & Co., 1887; 2nd edition 1888; University of Edinburgh Press, 3rd edition, 1967; reprint of 1888 edition, Baltimore, Maryland:

''African Life and Customs''

London: C. M. Phillips, 1908; reprint Baltimore, Maryland: Black Classic Press, 1994.

''West Africa Before Europe: and Other Addresses, Delivered in England in 1901 and 1903''

London: C. M. Phillips, 1905.

"The Elements of Permanent Influence"

Discourse Delivered at the 15th St. Presbyterian Church, Washington, DC, Sunday, 16 February 1890, Washington, DC: R. L. Pendleton (published by request), 1890 (hosted on Virtual Museum of Edward W. Blyden). * "Liberia as a Means, Not an End", Liberian Independence Oration: 26 July 1867; '' African Repository and Colonial Journal'', Washington, DC: November 1867. * "The Negro in Ancient History, Liberia: Past, Present, and Future", ''Methodist Quarterly Review'', Washington, DC: M'Gill & Witherow Printer. * "The Origin and Purpose of African Colonization", A Discourse Delivered at the 66th Anniversary of the

''African Repository and Colonial Journal''

Internet Archive, issues online {{DEFAULTSORT:Blyden, E. W. 1832 births 1912 deaths 19th-century Liberian writers 20th-century Liberian writers Americo-Liberian people Americo-Liberians of Igbo descent Classics educators English-language writers Ministers of foreign affairs of Liberia Liberian pan-Africanists Liberian Christian Zionists People from Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands Presidents of the University of Liberia Secretaries of the interior of Liberia Sierra Leone Creole people Sierra Leonean academics Sierra Leonean Christians Sierra Leonean pan-Africanists Academic staff of the University of Liberia People from the Danish West Indies

Americo-Liberian

Americo-Liberian people (also known as Congo people or Congau people),Cooper, Helene, ''The House at Sugar Beach: In Search of a Lost African Childhood'' (United States: Simon and Schuster, 2008), p. 6 are a Liberian ethnic group of African Am ...

educator, writer, diplomat, and politician who was primarily active in West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

. Born in the Danish West Indies

The Danish West Indies () or Danish Virgin Islands () or Danish Antilles were a Danish colony in the Caribbean, consisting of the islands of Saint Thomas with , Saint John () with , Saint Croix with , and Water Island.

The islands of St ...

, he joined the waves of black immigrants from the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.'' Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sin ...

who migrated to Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

. Blyden became a teacher for five years in the British West Africa

British West Africa was the collective name for British settlements in West Africa during the colonial period, either in the general geographical sense or the formal colonial administrative entity. British West Africa as a colonial entity was ...

n colony of Sierra Leone

The Colony and Protectorate of Sierra Leone (informally British Sierra Leone) was the British colonial administration in Sierra Leone from 1808 to 1961, part of the British Empire from the Abolitionism in the United Kingdom, abolitionism era un ...

in the early twentieth century. His major writings were on pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atla ...

, which later became influential throughout West Africa, attracting attention in countries such as the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

as well. His ideas went on to influence the likes of Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) (commonly known a ...

, George Padmore

George Padmore (28 June 1903 – 23 September 1959), born Malcolm Ivan Meredith Nurse, was a leading Pan-Africanist, journalist, and author. He left his native Trinidad in 1924 to study medicine in the United States, where he also joined the C ...

and Kwame Nkrumah

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (, 21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it gained ...

.

Blyden was recognised in his youth for his talents and drive; he was educated and mentored by John P. Knox, an American Protestant

Protestantism is the largest grouping of Christianity in the United States, Christians in the United States, with its combined Christian denomination, denominations collectively comprising about 43% of the country's population (or 141 million peo ...

minister in Sankt Thomas who encouraged him to continue his education in the United States. In 1850, Blyden was refused admission to three Northern theological seminaries because of his race. Knox encouraged him to go to Liberia, a colony set up for free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (; ) were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not enslaved. However, the term also applied to people born free who we ...

by the American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the repatriation of freeborn peop ...

. Blyden emigrated in 1850 and made his career and life there. He married into a prominent family and soon started working as a journalist. Blyden's ideas remain influential to this day.

Early life and education

Blyden was born on 3 August 1832 in Saint Thomas,Danish West Indies

The Danish West Indies () or Danish Virgin Islands () or Danish Antilles were a Danish colony in the Caribbean, consisting of the islands of Saint Thomas with , Saint John () with , Saint Croix with , and Water Island.

The islands of St ...

(now known as the American Virgin Islands), to free black parents who claimed descent from the Igbo people of present-day Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

. The family lived in an English speaking, Jewish neighborhood. Between 1842 and 1845 the family lived in Porto Bello, Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

, where Blyden discovered a facility for languages, becoming fluent in Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

.

According to the historian Hollis R. Lynch, in 1845 Blyden met the Reverend John P. Knox, a white American, who became pastor of the St. Thomas Protestant Dutch Reformed Church.Hollis R. Lynch''Edward Wilmot Blyden: Pan-Negro Patriot, 1832–1912''

New York: Oxford University Press, 1967, p. 4. Blyden and his family lived near the church, and Knox was impressed with the studious, intelligent boy. Knox became his mentor, encouraging Blyden's considerable aptitude for oratory and literature. Mainly because of his close association with Knox, the young Blyden decided to become a minister, which his parents encouraged. In May 1850, Blyden, accompanied by Reverend Knox's wife, went to the United States to enroll in

Rutgers

Rutgers University ( ), officially Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, is a public land-grant research university consisting of three campuses in New Jersey. Chartered in 1766, Rutgers was originally called Queen's College and was aff ...

Theological College, Knox's ''alma mater.'' He was refused admission due to his race. Efforts to enroll him in two other theological colleges also failed. Knox encouraged Blyden to go to Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

, the colony set up in the 1830s by the American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the repatriation of freeborn peop ...

(ACS) in West Africa, where he thought Blyden would be able to use his talents. Later in 1850, Blyden sailed to Liberia. One year later, Blyden enrolled in Alexander High School in Monrovia, where he studied theology, the classics, geography, mathematics, and Hebrew in his spare time. Blyden also acted as principal of the school when needed, and in 1858 he became the official principal of Alexander High school. That same year, Blyden was ordained as a Presbyterian minister.

Starting in 1860, Blyden corresponded with William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

, who would later become a significant Liberal leader and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Gladstone offered Blyden an opportunity to study in England in 1861, but Blyden declined due to his obligations in Liberia.

Marriage, family and legacy

Blyden married Sarah Yates, an

Blyden married Sarah Yates, an Americo-Liberian

Americo-Liberian people (also known as Congo people or Congau people),Cooper, Helene, ''The House at Sugar Beach: In Search of a Lost African Childhood'' (United States: Simon and Schuster, 2008), p. 6 are a Liberian ethnic group of African Am ...

from the prominent Yates family. She was the daughter of Hilary Yates and his wife. Her paternal uncle, Beverly Page Yates, served as vice-president of Liberia from 1856 to 1860 under President Stephen Allen Benson. Blyden and Sarah had three children together.

Later, while living for several years in Freetown

Freetown () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, e ...

, Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

, Blyden had a long-term relationship with Anna Erskine, a Liberian woman from Clay-Ashland who had moved to Freetown in 1877. She was a granddaughter of James Spriggs-Payne, who was twice elected as the President of Liberia

The president of the Republic of Liberia is the head of state and government of Liberia. The president serves as the leader of the executive branch and as commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces of Liberia.

Prior to the independence of Liber ...

. Blyden and Erskine had five children together. In the 21st century, many Blyden descendants living in Sierra Leone identify as part of the Creole population. Among these descendants is Sylvia Blyden, publisher of the ''Awareness Times''.

Blyden died on 7 February 1912 in Freetown, Sierra Leone, where he was buried at Racecourse Cemetery. In honour of him, the 20th-century Pan-Africanist George Padmore

George Padmore (28 June 1903 – 23 September 1959), born Malcolm Ivan Meredith Nurse, was a leading Pan-Africanist, journalist, and author. He left his native Trinidad in 1924 to study medicine in the United States, where he also joined the C ...

named his daughter Blyden.

Career

Soon after his immigration to Liberia in 1850, Blyden began work in journalism. He began as a correspondent for the ''Liberia Herald'' (the only newspaper in Liberia at the time) and was appointed editor from 1855 to 1856, during which he also authored his first pamphlet, "A Voice From Bleeding Africa". He also spent time in British colonies in West Africa, particularlyNigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

and Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

, writing for early newspapers in both colonies. In Sierra Leone, he was the founder and editor of ''The Negro'' newspaper in the early 1870s. He maintained ties with the American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the repatriation of freeborn peop ...

and published in their '' African Repository and Colonial Journal''.

In 1861 Blyden became professor of Greek and Latin at Liberia College. He was selected as president of the college, serving 1880–1884 during a period of expansion.

As a diplomat Blyden served as an ambassador for Liberia to Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. He also traveled to the United States where he spoke to major black churches about his work in Africa. Blyden believed that Black Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

could end their suffering of racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their Race (human categorization), race, ancestry, ethnicity, ethnic or national origin, and/or Human skin color, skin color and Hair, hair texture. Individuals ...

by returning to Africa and helping to develop it. He was criticized by African Americans who wanted to gain full civil rights in their birth nation of the United States and did not identify with Africa.

In suggesting a redemptive role for African Americans in Africa through what he called Ethiopianism, Blyden likened their suffering in the diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of birth, place of origin. The word is used in reference to people who identify with a specific geographic location, but currently resi ...

to that of the Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

; he supported the 19th-century Zionist

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

project of Jews returning to Palestine.''Black Zion : African American Religious Encounters with Judaism''edited by Yvonne Chireau, Nathaniel Deutsch; Oxford University Press, 1999, Google eBook, p. 15. In their book ''Israel in the Black American Perspective'', Robert G. Weisbord and Richard Kazarian write that in his booklet ''The Jewish Question'' (published in 1898, the year after the First Zionist Congress) Blyden describes that while travelling in the Middle East in 1866 he wanted to travel to "the original home of the Jews–to see Jerusalem and Mt. Zion, the joy of the whole earth". While in Jerusalem he visited the Western Wall. Blyden advocated for the Jewish settlement of Palestine and chided Jews for not taking advantage of the opportunity to live in their ancient homeland. Blyden was familiar with

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of Types of Zionism, modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organizat ...

and his book ''The Jewish State

( German, , commonly rendered as ''The Jewish State'') is a pamphlet written by Theodor Herzl and published in February 1896 in Leipzig and Vienna by M. Breitenstein's Verlags-Buchhandlung. It is subtitled with ''"Versuch einer modernen Lösu ...

'', praising it for expressing ideas that "have given such an impetus to the real work of the Jews as will tell with enormous effect upon their future history".

Later in life Blyden became involved in Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

and concluded that it was a more "African" religion than Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

for African Americans and Americo-Liberians.

Participating in the development of Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

, Blyden served as the Secretary of State under President Daniel Bashiel Warner from 1864 to 1865. He later served as Secretary of the Interior under President Anthony W. Gardiner from 1880 to 1882. Blyden contested the 1885 presidential election for the Republican Party but lost to True Whig incumbent Hilary R. W. Johnson.

From 1901 to 1906, Blyden directed the education of Sierra Leonean Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

s at an institution in Sierra Leone where he lived in Freetown

Freetown () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, e ...

. This is when he had his relationship with Anna Erskine; they had five children together. He became passionate about Islam during this period, recommending it to African Americans as the major religion most in keeping with their historic roots in Africa.

Writings

As a writer, Blyden has been regarded by some as the "father ofPan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atla ...

" and is noted as one of the first people to articulate a notion of "African Personality" and the uniqueness of the "African race". His ideas have influenced many twentieth-century figures including Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) (commonly known a ...

, George Padmore

George Padmore (28 June 1903 – 23 September 1959), born Malcolm Ivan Meredith Nurse, was a leading Pan-Africanist, journalist, and author. He left his native Trinidad in 1924 to study medicine in the United States, where he also joined the C ...

and Kwame Nkrumah

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (, 21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it gained ...

. His major work, ''Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race'' (1887), promoted the idea that practicing Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

was more unifying and fulfilling for Africans than Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

. Blyden believed that practicing Christianity had a demoralizing effect on Africans, although he continued to be a Christian. He thought Islam was more authentically African, as it had been brought to Sub-Saharan areas by people from North Africa.

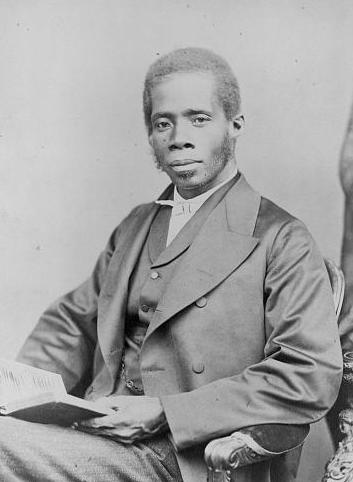

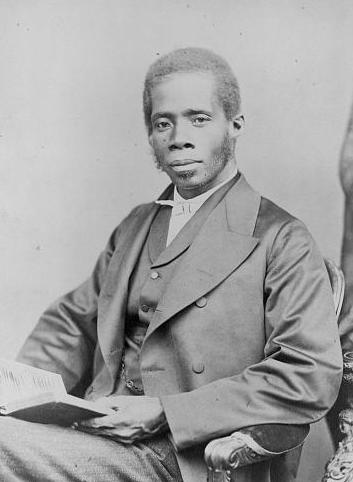

His book quickly became controversial. At first many people did not believe that an African had written it; his promotion of Islam was disputed. In later printings, Blyden included his photograph as the frontispiece.

His book included the following:

'Let us do away with the sentiment of Race. Let us do away with our African personality and be lost, if possible, in another Race.' This is as wise or as philosophical as to say, let us do away with gravitation, with heat and cold and sunshine and rain. Of course, the Race in which these persons would be absorbed is the dominant race, before which, in cringing self-surrender and ignoble self-suppression they lie in prostrate admiration.Due to his belief in Ethiopianism and that

African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

could return to Africa and help in the rebuilding of the continent, Blyden saw Zionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

as a model to look up to and supported the creation of a Jewish state in Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, praising Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of Types of Zionism, modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organizat ...

as the creator of "that marvelous movement called Zionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

". Herzl died in 1908 roughly 44 years before the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, also known as the First Arab–Israeli War, followed the 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine, civil war in Mandatory Palestine as the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. The civil war becam ...

.Bornstein, George"The Colors of Zion: Black, Jewish, and Irish Nationalisms at the turn of the Century"

''Modernism/modernity'' 12.3 (2005), Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 369–84.

Works

Books

Call of Providence to the Descendants of Africa in America", A Discourse Delivered to Coloured Congregations in the Cities of New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Harrisburg, during the Summer of 1862, in ''Liberia's Offering: Being Addresses, Sermons, etc.''

New York: John A. Gray, 1862.

''Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race''

London, W. B. Whittingham & Co., 1887; 2nd edition 1888; University of Edinburgh Press, 3rd edition, 1967; reprint of 1888 edition, Baltimore, Maryland:

Black Classic Press

Black Classic Press (BCP) is an African-American book publishing company, founded by W. Paul Coates in 1978. Since then, BCP has published original titles by notable authors including Walter Mosley, John Henrik Clarke, E. Ethelbert Miller, Yosef ...

, 1994 (edition on Googlebooks).''African Life and Customs''

London: C. M. Phillips, 1908; reprint Baltimore, Maryland: Black Classic Press, 1994.

''West Africa Before Europe: and Other Addresses, Delivered in England in 1901 and 1903''

London: C. M. Phillips, 1905.

Essays and speeches

* "Africa for the Africans", '' African Repository and Colonial Journal'', Washington, DC: January 1872. * "The Call of Providence to the Descendants of Africa in America", A Discourse Delivered to Coloured Congregations in the Cities of New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Harrisburg, during the Summer of 1862, in ''Liberia's Offering: Being Addresses, Sermons, etc.'', New York: John A. Gray, 1862."The Elements of Permanent Influence"

Discourse Delivered at the 15th St. Presbyterian Church, Washington, DC, Sunday, 16 February 1890, Washington, DC: R. L. Pendleton (published by request), 1890 (hosted on Virtual Museum of Edward W. Blyden). * "Liberia as a Means, Not an End", Liberian Independence Oration: 26 July 1867; '' African Repository and Colonial Journal'', Washington, DC: November 1867. * "The Negro in Ancient History, Liberia: Past, Present, and Future", ''Methodist Quarterly Review'', Washington, DC: M'Gill & Witherow Printer. * "The Origin and Purpose of African Colonization", A Discourse Delivered at the 66th Anniversary of the

American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the repatriation of freeborn peop ...

, Washington, DC, 14 January 1883, Washington, 1883.

* E. W. Blyden M.A., ''Report on the Falaba Expedition 1872'', Addressed to His Excellency Governor J. Pope Hennessy, C.M.G., Published by authority Freetown, Sierra Leone. Printed at Government Office, 1872.

* "Liberia at the American Centennial", ''Methodist Quarterly Review'', July 1877.

* "America in Africa," ''Christian Advocate'' I, 28 July 1898, II, 4 August 1898.

* "The Negro in the United States", '' A.M.E. Church Review'', January 1900.

See also

Pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atla ...

References

External links

*''African Repository and Colonial Journal''

Internet Archive, issues online {{DEFAULTSORT:Blyden, E. W. 1832 births 1912 deaths 19th-century Liberian writers 20th-century Liberian writers Americo-Liberian people Americo-Liberians of Igbo descent Classics educators English-language writers Ministers of foreign affairs of Liberia Liberian pan-Africanists Liberian Christian Zionists People from Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands Presidents of the University of Liberia Secretaries of the interior of Liberia Sierra Leone Creole people Sierra Leonean academics Sierra Leonean Christians Sierra Leonean pan-Africanists Academic staff of the University of Liberia People from the Danish West Indies