Edward Watkin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Edward William Watkin, 1st Baronet (26 September 1819 – 13 April 1901) was a

Watkin was born in

Watkin was born in

Watkin's last project was the construction of a large iron tower, called Watkin's Tower, in Wembley Park, north-west London. The tower was to be the centrepiece of a large public

Watkin's last project was the construction of a large iron tower, called Watkin's Tower, in Wembley Park, north-west London. The tower was to be the centrepiece of a large public

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

Member of Parliament and railway entrepreneur. He was an ambitious visionary, and presided over large-scale railway engineering projects to fulfil his business aspirations, eventually rising to become chairman of nine different British railway companies.

Among his more notable projects were: his expansion of the Metropolitan Railway

The Metropolitan Railway (also known as the Met) was a passenger and goods railway that served London from 1863 to 1933, its main line heading north-west from the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the Middlesex su ...

, part of today's London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or as the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent home counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The Undergro ...

; the construction of the Great Central Main Line, a purpose-built high-speed railway line; the creation of a pleasure garden with a partially constructed iron tower at Wembley; and a failed attempt to dig a Channel Tunnel

The Channel Tunnel (), sometimes referred to by the Portmanteau, portmanteau Chunnel, is a undersea railway tunnel, opened in 1994, that connects Folkestone (Kent, England) with Coquelles (Pas-de-Calais, France) beneath the English Channel at ...

under the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

to connect his railway empire to the French rail network.

Early life

Watkin was born in

Watkin was born in Salford

Salford ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Greater Manchester, England, on the western bank of the River Irwell which forms its boundary with Manchester city centre. Landmarks include the former Salford Town Hall, town hall, ...

, Lancashire, the son of wealthy cotton merchant Absalom Watkin,. After a private education, Watkin worked in his father's mill business. Watkin's father was closely involved in the Anti-Corn Law League, and Edward soon joined him, rising to become a key League organiser in Manchester. Through this work, Watkin gained the friendship of the Radical leader Richard Cobden, with whom he remained in contact for the rest of Cobden's life.

From 1839 to 1840 Watkin was one of the directors of the Manchester Athenaeum. In 1843 he wrote a pamphlet entitled "A Plea for Public Parks" and was involved in a committee which successfully sought the provision of parks in Manchester and Salford. He also took a prominent role in the Saturday Half-holiday Movement. In 1845, Watkin co-founded the '' Manchester Examiner'', by which time he had become a partner in his father's business.

Railways

Watkin began to show an interest in railways and in 1845 he took on the secretaryship of the Trent Valley Railway, which was sold the following year to theLondon and North Western Railway

The London and North Western Railway (LNWR, L&NWR) was a British railway company between 1846 and 1922. In the late 19th century, the LNWR was the largest joint stock company in the world.

Dubbed the "Premier Line", the LNWR's main line connec ...

(LNWR), for £438,000. He then became assistant to Captain Mark Huish, general manager of the LNWR. He visited USA and Canada and in 1852 he published a book about the railways in these countries. Back in Great Britain he was appointed secretary of the Worcester and Hereford Railway.

In January 1854 he became the general manager of the Manchester Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR), a position held until 1861. In 1863 he was persuaded to return as a director of the company and shortly afterward became chairman, holding the position from 1864 to 1894. He was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

ed in 1868 and made a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

in 1880.

Manager from 1858, then president 1862–69, of the Grand Trunk Railway

The Grand Trunk Railway (; ) was a Rail transport, railway system that operated in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario and in the List of states and territories of the United States, American sta ...

of eastern Canada, he promoted the Intercolonial Railway

The Intercolonial Railway of Canada , also referred to as the Intercolonial Railway (ICR), was a historic Canada, Canadian railway that operated from 1872 to 1918, when it became part of Canadian National Railways. As the railway was also compl ...

, which eventually connected Halifax with the GTR system in Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

. His grand vision was a transcontinental railway lying largely within Canada, but owing to the sparse population west of Lake Superior

Lake Superior is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. Lake Michigan–Huron has a larger combined surface area than Superior, but is normally considered tw ...

, the scheme could not be profitable in the absence of government financial backing. Opposition to the idea within the company led to Watkin's ouster. The GTR would later miss various opportunities to build a viable Canadian transcontinental railway.

Abroad, he helped to build the Athens–Piraeus Electric Railways, advised on the Indian Railways

Indian Railways is a state-owned enterprise that is organised as a departmental undertaking of the Ministry of Railways (India), Ministry of Railways of the Government of India and operates India's national railway system. , it manages the fou ...

and organised transport in the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (, ; ) was a Belgian colonial empire, Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Repu ...

.

Watkin was involved with other railway companies. In 1866 he became a director of the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a History of rail transport in Great Britain, British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, ...

and in January 1868 the Great Eastern Railway. In fact it was Watkin who recommended Robert Cecil, who is credited with leading the GER out of its financial crisis. Watkin resigned as a director of the GER in August 1872.

By 1881 he was a director of nine railways and trustee of a tenth. These included the Cheshire Lines Committee, the East London, the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire, the Manchester, South Junction & Altrincham, the Metropolitan, the Oldham, Ashton & Guide Bridge, the Sheffield & Midland Joint, the South Eastern, the Wigan Junction and the New York, Lake Erie and Western railways.

He was instrumental in the creation of the MS&LR's 'London Extension', Sheffield to Marylebone, the Great Central Main Line, opened in 1899.

Channel tunnel

For Watkin, opening an independent route to London was crucial for the long-term survival and development of the MS&LR, but it was also one part of a grander scheme: a line from Manchester to Paris. His chairmanships of the South Eastern Railway, the Metropolitan Railway, in addition to the MS&LR meant that he controlled railways from England's south coast ports, through London and (with the London Extension) through the Midlands to the industrial cities of the North; he was also on the board of the Chemin de Fer du Nord, a French railway company based inCalais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a French port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Calais is the largest city in Pas-de-Calais. The population of the city proper is 67,544; that of the urban area is 144,6 ...

. Watkin's ambitious plan was to develop a railway route which could carry passenger trains directly from Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

and Manchester to Paris, crossing from Britain to France via a tunnel under the English Channel. The Great Central Railway's main line to London was also built to a comparatively generous structure gauge, but contrary to popular belief it was not built to a 'continental' gauge, not least because there were no agreed dimensions for such a gauge until the Berne Gauge Convention was signed in 1912. Healy mentions two bridges which were built to "unusual dimensions ... to provide for possible widenings in case the Channel Tunnel project ever took off ..."

Watkin started his tunnel works with the South Eastern Railway in 1880–81. Digging began at Shakespeare Cliff between Folkestone

Folkestone ( ) is a coastal town on the English Channel, in Kent, south-east England. The town lies on the southern edge of the North Downs at a valley between two cliffs. It was an important harbour, shipping port, and fashionable coastal res ...

and Dover

Dover ( ) is a town and major ferry port in Kent, southeast England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies southeast of Canterbury and east of Maidstone. ...

and reached a length of . The project was highly controversial and fears grew of the tunnel being used as a route for a possible French invasion of Great Britain; notable opponents of the project were the War Office Scientific Committee, Lord Wolseley and Prince George, Duke of Cambridge;

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

reportedly found the tunnel scheme "objectionable". Watkin was skilled at public relations

Public relations (PR) is the practice of managing and disseminating information from an individual or an organization (such as a business, government agency, or a nonprofit organization) to the public in order to influence their perception. Pu ...

and attempted to garner political support for his project, inviting such high-profile guests as the Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. The ...

and Princess of Wales

Princess of Wales (; ) is a title used since the 14th century by the wife of the Prince of Wales. The Princess is the apparent future queen consort, as "Prince of Wales" is a title reserved by custom for the heir apparent to the Monarchy of the ...

, Liberal Party Leader William Gladstone and the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

to submarine champagne receptions in the tunnel. In spite of his attempts at winning support, his tunnel project was blocked by parliament, then cancelled in the interests of national security. The original entrance to Watkin's tunnel works remains in the cliff face but is now closed for safety reasons.

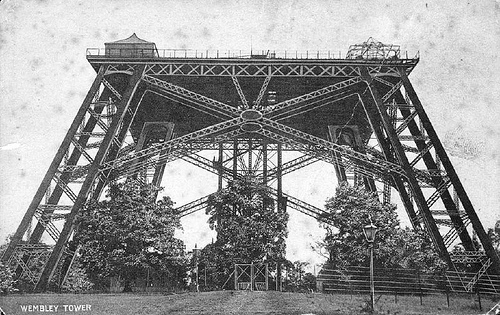

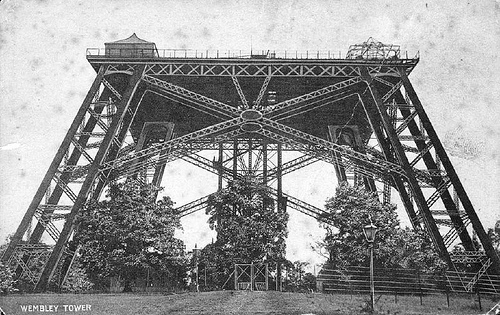

Wembley Park and Watkin's Tower

Watkin's last project was the construction of a large iron tower, called Watkin's Tower, in Wembley Park, north-west London. The tower was to be the centrepiece of a large public

Watkin's last project was the construction of a large iron tower, called Watkin's Tower, in Wembley Park, north-west London. The tower was to be the centrepiece of a large public amusement park

An amusement park is a park that features various attractions, such as rides and games, and events for entertainment purposes. A theme park is a type of amusement park that bases its structures and attractions around a central theme, often fea ...

which he opened in May 1894 to attract London passengers onto his Metropolitan Railway. The park was served by Wembley Park station, which officially opened in the same month, though it had in fact been open on Saturdays since October 1893 to cater for football matches in the pleasure gardens.

Watkin's vision of Wembley Park as a day-out destination for Londoners had far-reaching consequences, shaping the history and use of the area to the present day. Without Watkin's pleasure gardens and station it is unlikely that the British Empire Exhibition

The British Empire Exhibition was a colonial exhibition held at Wembley Park, London England from 23 April to 1 November 1924 and from 9 May to 31 October 1925.

Background

In 1920 the Government of the United Kingdom, British Government decide ...

would have been held at Wembley, which in turn would have prevented Wembley becoming either synonymous with English football or a successful popular music venue. Without Watkin, it is likely that the district would have simply become inter-war semi-detached suburbia like the rest of west London.

The tower was intended to rival the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower from 1887 to 1889.

Locally nicknamed "''La dame de fe ...

in Paris. The foundations of the tower were laid in 1892, the first stage was completed in September 1895 and it was opened to the public in 1896.

After an initial burst of popularity, the tower failed to draw large crowds. Of the 100,000 visitors to the Park in 1896 rather less than a fifth paid to go up the Tower. Furthermore, the marshy site proved unsuitable for such a structure. Whether the original design (which was to have had eight legs) would have distributed the weight more evenly cannot be known, but by 1896 the four-legged tower was clearly tilting. In addition, Watkin had retired from the chairmanship of the Metropolitan in 1894 after suffering a stroke, so the tower's enthusiastic champion was gone. In June 1897 the tower was illuminated for Queen Victoria's 60th Jubilee, but it was never extended beyond the first stage.

In 1902 the Tower, now known as ‘Watkin's Folly’, was declared unsafe (though this was because of concerns about the safety of the lifts, rather than directly about the subsidence) and closed to the public. In 1904 it was decided to demolish the structure, a process that ended with the foundations being destroyed by explosives in 1907, leaving four large holes in the ground. The Empire Stadium (later known as Wembley Stadium) was built on the site in 1923.

Political career

Throughout his life, Watkin was a strong supporter of Manchester Liberalism. This did not equate to consistent support for a single party. Watkin was first elected Liberal Member of Parliament forGreat Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth ( ), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside resort, seaside town which gives its name to the wider Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. Its fishing industry, m ...

(1857–1858), and then Stockport

Stockport is a town in Greater Manchester, England, south-east of Manchester, south-west of Ashton-under-Lyne and north of Macclesfield. The River Goyt, Rivers Goyt and River Tame, Greater Manchester, Tame merge to create the River Mersey he ...

(1864–1868). He unsuccessfully contested the East Cheshire seat in 1869. He was knighted in 1868 and became a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

in 1880. He was also High Sheriff of Cheshire

This is a list of Sheriffs (and after 1 April 1974, High Sheriffs) of Cheshire.

The High Sheriff, Sheriff is the oldest secular office under the The Crown, Crown. Formerly the Sheriff was the principal law officer, law enforcement officer in th ...

in 1874.

In 1874, he was elected Liberal MP for Hythe in Kent. He increasingly moved away from the Liberal party under William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

and in 1880 it was claimed that he had taken the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

whip. He never stood for election as a Conservative and continued to sit with the Liberals. Between 1880 and 1886, he was regarded variously as a Liberal, a Conservative and an independent. In 1886, he voted against Gladstone's Irish Home Rule bill and was thereafter commonly described as a Liberal Unionist.

The confusion over his status came to the fore when he resigned his Hythe seat in 1895. The Liberal Unionists and the Conservatives were in alliance and each claimed incumbency and the right to nominate his replacement. Watkin for his part insisted that he was a Liberal, albeit one who had moved away from the official party. The Conservative Aretas Akers-Douglas commented that no one knew what his politics were, except that he had voted for anyone or anything to get support for his Channel Tunnel. The Conservatives forced the Liberal Unionists to back down and won the seat in the 1895 United Kingdom general election

The 1895 United Kingdom general election was held from 13 July to 7 August 1895. The result was a Conservative parliamentary majority of 153.

William Ewart Gladstone, William Gladstone had retired as prime minister the previous year, and Queen ...

.

Personal life

Watkin lived at Rose Hill, a large house in Northenden,Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

. The family home was purchased by his father in 1832 and Edward inherited it upon his father's death in 1861.

Watkin married Mary Briggs Mellor in 1845, with whom he had two children. Their son, Alfred Mellor Watkin, became locomotive superintendent of the South Eastern Railway in 1876 and Member of Parliament for the Great Grimsby constituency in 1877. A daughter, Harriette Sayer Watkin, was born in 1850. Mary Watkin died on 8 March 1888.

After four years a widower, Watkin married Ann Ingram, widow of Herbert Ingram, on 6 April 1892.

Edward Watkin died on 13 April 1901 and was buried in the family grave in the churchyard of St Wilfrid's, Northenden, where a memorial plaque commemorates his life.

Notes

References

* * * * * * *Further reading

* * *External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Watkin, Edward Liberal Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies People associated with transport in London 1819 births 1901 deaths 1 Whig (British political party) MPs for English constituencies UK MPs 1857–1859 UK MPs 1859–1865 UK MPs 1865–1868 UK MPs 1874–1880 UK MPs 1880–1885 UK MPs 1885–1886 UK MPs 1886–1892 UK MPs 1892–1895 Channel Tunnel Great Central Railway people South Eastern and Chatham Railway people Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway High sheriffs of Cheshire Politics of the Borough of Great Yarmouth Liberal Unionist Party MPs for English constituencies Directors of the Great Eastern Railway Railway executives British railway entrepreneurs Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Stockport 19th-century British businesspeople