Edward Lhuyd on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward Lhuyd (1660– 30 June 1709), also known as Edward Lhwyd and by

Edward Lhuyd (1660– 30 June 1709), also known as Edward Lhwyd and by

The first written record of a

The first written record of a

Edward Lhwyd, c.1660-1709, Naturalist, Antiquary, Philologist

', University of Wales Press, 2022 (Scientists of Wales)

from the Canolfan Edward Llwyd, a centre for the study of science through Welsh {{DEFAULTSORT:Lhuyd, Edward 1660 births 1709 deaths Scientists from Shropshire People educated at Oswestry School Alumni of Jesus College, Oxford Celtic studies scholars Welsh botanists 17th-century botanists Welsh curators Fellows of the Royal Society People associated with the Ashmolean Museum Keepers and directors of the Ashmolean Museum Language comparison Cornish language 17th-century Welsh scientists 17th-century antiquarians 18th-century Welsh antiquarians Linguists from Wales Welsh geographers

other spellings

Other often refers to:

* Other (philosophy), a concept in psychology and philosophy

Other or The Other may also refer to:

Film and television

* The Other (1913 film), ''The Other'' (1913 film), a German silent film directed by Max Mack

* The Ot ...

, was a Welsh scientist, geographer, historian and antiquary. He was the second Keeper of the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

's Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street in Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University ...

, and published the first catalogue of fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s, the .

Name

Lhuyd ( ; ) is an archaic spelling of the same Welshsurname

In many societies, a surname, family name, or last name is the mostly hereditary portion of one's personal name that indicates one's family. It is typically combined with a given name to form the full name of a person, although several give ...

now usually rendered as Lloyd or Llwyd, from ("gray

Grey (more frequent in British English) or gray (more frequent in American English) is an intermediate color between black and white. It is a neutral or achromatic color, meaning that it has no chroma. It is the color of a cloud-covered s ...

"). It also appears frequently as Lhwyd; less often as Lhwydd, Llhwyd, Llwid and Floyd; and latinized as ( or ) , frequently abbreviated , and as and in some scientific name

In Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin gramm ...

s. The English and Latin forms are also sometimes combined as ''Edward Luidius''.

Life

Lhuyd was born in 1660, in Loppington,Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, the illegitimate son of Edward Llwyd or Lloyd of Llanforda, Oswestry

Oswestry ( ; ) is a market town, civil parish and historic railway town in Shropshire, England, close to the England–Wales border, Welsh border. It is at the junction of the A5 road (Great Britain), A5, A483 road, A483 and A495 road, A495 ro ...

, and Bridget Pryse of Llansantffraid, near Talybont, Cardiganshire

Ceredigion (), historically Cardiganshire (, ), is a county in the west of Wales. It borders Gwynedd across the Dyfi estuary to the north, Powys to the east, Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. Ab ...

, in 1660. His family belonged to the gentry of southwest Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

. Though well established, the family was not wealthy. His father experimented with agriculture and industry in a manner that impinged on the new science of the day. The son attended and later taught at Oswestry Grammar School, and in 1682 went up to Jesus College, Oxford

Jesus College (in full: Jesus College in the University of Oxford of Queen Elizabeth's Foundation) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. It is in the centre of the city, on a site between Turl Street, Ship ...

, but dropped out before graduation

A graduation is the awarding of a diploma by an educational institution. It may also refer to the ceremony that is associated with it, which can also be called Commencement speech, commencement, Congregation (university), congregation, Convocat ...

. In 1684, he was appointed to assist Robert Plot

Robert Plot (13 December 1640 – 30 April 1696) was an English naturalist and antiquarian who was the first professor of chemistry at the University of Oxford and the first keeper of the Ashmolean Museum.

Early life and education

Born in Bor ...

, Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street in Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University ...

(which at that time was in Broad Street), and became the second Keeper himself in 1690, holding the post until his death in 1709.

While working at the Ashmolean Museum, Lhuyd travelled extensively. A visit to Snowdonia

Snowdonia, or Eryri (), is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in North Wales. It contains all 15 mountains in Wales Welsh 3000s, over 3000 feet high, including the country's highest, Snowdon (), which i ...

in 1688 allowed him to compile for John Ray

John Ray Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (November 29, 1627 – January 17, 1705) was a Christian England, English Natural history, naturalist widely regarded as one of the earliest of the English parson-naturalists. Until 1670, he wrote his ...

's a list of flora

Flora (: floras or florae) is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. The corresponding term for animals is ''fauna'', and for f ...

local to that region. After 1697, Lhuyd visited every county in Wales, then travelled to Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

, Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

and the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

. In 1699, it became possible through funding from his friend Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

for him to publish the first catalogue ever of fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s, his . These had been collected in England, mostly in Oxford, and are now held in the Ashmolean.

Lhuyd received a MA ''honoris causa

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hono ...

'' from the University of Oxford in 1701 and a fellowship of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1708.

In 1696, Lluyd transcribed much of the Latin inscription on the 9th-century Pillar of Eliseg near Valle Crucis Abbey, Denbighshire

Denbighshire ( ; ) is a county in the north-east of Wales. It borders the Irish Sea to the north, Flintshire to the east, Wrexham to the southeast, Powys to the south, and Gwynedd and Conwy to the west. Rhyl is the largest town, and Ruthi ...

. The inscription subsequently became almost illegible due to weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals (as well as wood and artificial materials) through contact with water, atmospheric gases, sunlight, and biological organisms. It occurs '' in situ'' (on-site, with little or no move ...

, but Lhuyd's transcript seems to have been remarkably accurate.

Lhuyd was also responsible for the first scientific description and naming of what we would now recognize as a dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

: the sauropod

Sauropoda (), whose members are known as sauropods (; from '' sauro-'' + '' -pod'', 'lizard-footed'), is a clade of saurischian ('lizard-hipped') dinosaurs. Sauropods had very long necks, long tails, small heads (relative to the rest of their b ...

tooth

A tooth (: teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, tea ...

'' Rutellum impicatum''.

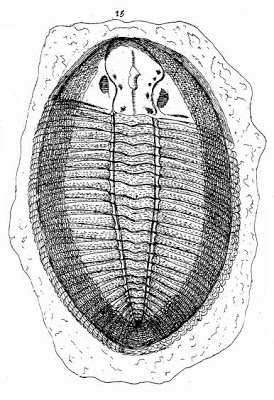

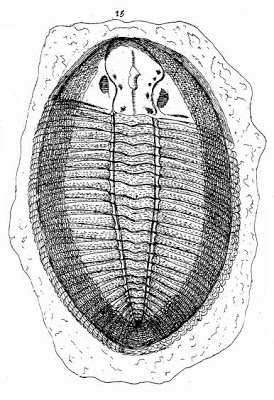

The first written record of a

The first written record of a trilobite

Trilobites (; meaning "three-lobed entities") are extinction, extinct marine arthropods that form the class (biology), class Trilobita. One of the earliest groups of arthropods to appear in the fossil record, trilobites were among the most succ ...

was by Lhuyd in a letter to Martin Lister

Martin Lister (12 April 1639 – 2 February 1712) was an English natural history, naturalist and physician. His daughters Anne Lister (illustrator), Anne and Susanna Lister, Susanna were two of his illustrators and engravers.

J. D. Woodley, 'L ...

in 1688 and published (1869) in his ''Lithophylacii Britannici Ichnographia''. It is a fleeting mention and he simply identifies his find as a "skeleton of some flat fish". The trilobite is nowadays identified as '' Ogygiocarella debuchii'' Brongniart, 1822.

Pioneering linguist

In the late 17th century, Lhuyd was contacted by a group of scholars led by John Keigwin of Mousehole, who sought to preserve and further theCornish language

Cornish (Standard Written Form: or , ) is a Southwestern Brittonic language, Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. Along with Welsh language, Welsh and Breton language, Breton, Cornish descends from Common Brittonic, ...

. He accepted their invitation to travel there and study the language. Early Modern Cornish was the subject of a paper published by Lhuyd in 1702; it differs from the medieval language in having a considerably simpler structure and grammar.

In 1707, having been assisted in his research by a fellow Welsh scholar, Moses Williams, Lhuyd published the first volume of '' Archæologia Britannica''. This has an important linguistic description of Cornish, which is noted all the more for the understanding of historical linguistics it shows. Some of the ideas commonly attributed to linguists of the 19th century have their roots in this work by Lhuyd, who was "considerably more sophisticated in his methods and perceptions than illiamJones".

Lhuyd noted a similarity between two language families: Brythonic or P–Celtic ( Breton, Cornish and Welsh) and Goidelic

The Goidelic ( ) or Gaelic languages (; ; ) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historically formed a dialect continuum stretching from Ireland through the Isle o ...

or Q–Celtic ( Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

). He argued that both families were derived from the Continental Celtic languages

The Continental Celtic languages are the now-extinct group of the Celtic languages that were spoken on the continent of Europe and in central Anatolia, as distinguished from the Insular Celtic languages of the British Isles, Ireland and Brittany. ...

; the Brythonic languages originated in the Gaulish

Gaulish is an extinct Celtic languages, Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium, ...

language once spoken and written by the Gauls

The Gauls (; , ''Galátai'') were a group of Celts, Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age Europe, Iron Age and the Roman Gaul, Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). Th ...

of Pre-Roman France and the Goidelic languages are derived from the Celtiberian language

Celtiberian or Northeastern Hispano-Celtic is an extinct Indo-European language of the Celtic branch spoken by the Celtiberians in an area of the Iberian Peninsula between the headwaters of the Douro, Tagus, Júcar and Turia rivers and the ...

once spoken in the Pre-Roman Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

, which includes modern Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

. He concluded that as these languages were of Celt

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

ic origin, those who spoke them were Celts. From the 18th century, peoples of Brittany, Cornwall, Ireland, the Isle of Man, Scotland and Wales were known increasingly as Celts. They are seen to this day as modern Celtic nations

The Celtic nations or Celtic countries are a cultural area and collection of geographical regions in Northwestern Europe where the Celtic languages and cultural traits have survived. The term ''nation'' is used in its original sense to mean a ...

.

Death and legacy

On his travels, Lhuyd developedasthma

Asthma is a common long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wh ...

, which eventually led to his death from pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (Pulmonary pleurae, pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant d ...

in Oxford in 1709. He died in his room in the Ashmolean Museum, aged just 49, and was buried in the Welsh aisle of the church of St Michael at the Northgate.

The Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

bryozoan species (originally described as ''Membranipora lhuydi'') is named in his honour. The Snowdon lily ('' Gagea serotina'') was for a time called ''Lloydia serotina'' after Lhuyd.

Cymdeithas Edward Llwyd, the National Naturalists' Society of Wales, is named after him. On 9 June 2001 a bronze bust of him was unveiled by Dafydd Wigley, a former Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru ( ; , ; officially Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, and often referred to simply as Plaid) is a centre-left, Welsh nationalist list of political parties in Wales, political party in Wales, committed to Welsh independence from th ...

leader, outside the University of Wales

The University of Wales () is a confederal university based in Cardiff, Wales. Founded by royal charter in 1893 as a federal university with three constituent colleges – Aberystwyth, Bangor and Cardiff – the university was the first universit ...

Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies in Aberystwyth

Aberystwyth (; ) is a University town, university and seaside town and a community (Wales), community in Ceredigion, Wales. It is the largest town in Ceredigion and from Aberaeron, the county's other administrative centre. In 2021, the popula ...

, next to the National Library of Wales

The National Library of Wales (, ) in Aberystwyth is the national legal deposit library of Wales and is one of the Welsh Government sponsored bodies. It is the biggest library in Wales, holding over 6.5 million books and periodicals, and the l ...

. The sculptor was John Meirion Morris; the inscription on the plinth, carved by Ieuan Rees, reads "" ("linguist, antiquary, naturalist").

References

Citations

Bibliography

* . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * .Further reading

* Brynley Roberts,Edward Lhwyd, c.1660-1709, Naturalist, Antiquary, Philologist

', University of Wales Press, 2022 (Scientists of Wales)

External links

from the Canolfan Edward Llwyd, a centre for the study of science through Welsh {{DEFAULTSORT:Lhuyd, Edward 1660 births 1709 deaths Scientists from Shropshire People educated at Oswestry School Alumni of Jesus College, Oxford Celtic studies scholars Welsh botanists 17th-century botanists Welsh curators Fellows of the Royal Society People associated with the Ashmolean Museum Keepers and directors of the Ashmolean Museum Language comparison Cornish language 17th-century Welsh scientists 17th-century antiquarians 18th-century Welsh antiquarians Linguists from Wales Welsh geographers