Edict Of Expulsion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Edict of Expulsion was a royal decree expelling all

The Edict of Expulsion was a royal decree expelling all

Following the expulsion, the Crown seized Jewish property. Debts with a value of £20,000 were collated from the ' from each town with a Jewish settlement. In December, Hugh of Kendall was appointed to dispose of the property seized from the Jewish refugees, the most-valuable of which consisted of houses in London. Some of the property was given away to courtiers, the Church and the royal family's circle in a total of 85 grants. William Burnell received property in

Following the expulsion, the Crown seized Jewish property. Debts with a value of £20,000 were collated from the ' from each town with a Jewish settlement. In December, Hugh of Kendall was appointed to dispose of the property seized from the Jewish refugees, the most-valuable of which consisted of houses in London. Some of the property was given away to courtiers, the Church and the royal family's circle in a total of 85 grants. William Burnell received property in

The permanent expulsion of Jews from England and tactics employed before it, such as attempts at forced conversion, are widely seen as setting a significant precedent and an example for the 1492

The permanent expulsion of Jews from England and tactics employed before it, such as attempts at forced conversion, are widely seen as setting a significant precedent and an example for the 1492

When England Expelled the Jews

by Rabbi Menachem Levine, Aish.com

England related articles

in ''

National Archive educational resource on the Expulsion

{{DEFAULTSORT:Edict Of Expulsion 1290 in England 1290s in law 13th-century Judaism Antisemitism in England Expulsion Edward I of England Expulsions of Jews Jewish English history Medieval Jewish history Religious expulsion orders Sephardi Jews topics Ethnic cleansing in Europe

The Edict of Expulsion was a royal decree expelling all

The Edict of Expulsion was a royal decree expelling all Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

from the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from the late 9th century, when it was unified from various Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland to f ...

that was issued by Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 125 ...

on 18 July 1290; it was the first time a European state is known to have permanently banned their presence. The date of issuance was most likely chosen because it was a Jewish holy day, the ninth of Ab, which commemorates the destruction of Jerusalem and other disasters the Jewish people have experienced. Edward told the sheriffs of all counties he wanted all Jews expelled before All Saints' Day (1 November) that year.

Jews were allowed to leave England with cash and personal possessions but outstanding debts, homes, and other buildings—including synagogues and cemeteries—were forfeit to the king. While there are no recorded attacks on Jews during the departure on land, there were acts of piracy in which Jews died, and others were drowned as a result of being forced to cross the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

at a time of year when dangerous storms are common. There is evidence from personal names of Jewish refugees settling in Paris and other parts of France, as well as Italy, Spain and Germany. Documents taken abroad by the Anglo-Jewish diaspora have been found as far away as Cairo. Jewish properties were sold to the benefit of the Crown, Queen Eleanor, and selected individuals, who were given grants of property.

The edict was not an isolated incident but the culmination of increasing antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

in England. During the reigns of Henry III and Edward I, anti-Jewish prejudice was used as a political tool by opponents of the Crown, and later by Edward and the state itself. Edward took measures to claim credit for the expulsion and to define himself as the protector of Christians against Jews, and following his death, he was remembered and praised for the expulsion. The expulsion had the lasting effect of embedding antisemitism into English culture, especially in the medieval and early modern period; such antisemitic beliefs included that England was unique because there were no Jews, and that the English had superseded the Jews as God's chosen people. The expulsion edict remained in force for the rest of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

but was overturned more than 365 years later during the Protectorate

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, was the English form of government lasting from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659, under which the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotl ...

, when in 1656, Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

informally permitted the resettlement of the Jews in England.

Background

The first Jewish communities in theKingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from the late 9th century, when it was unified from various Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland to f ...

were recorded some time after the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

in 1066, moving from William the Conqueror

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was D ...

's towns in northern France. Jews were viewed as being under the direct jurisdiction and property of the king, making them subject to his whims. The monarch could tax or imprison Jews as he wished, without reference to anyone else.. A very small number of Jews were wealthy because Jews were allowed to lend money at interest while the Church forbade Christians from doing so, which was regarded as the sin of usury

Usury () is the practice of making loans that are seen as unfairly enriching the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is charged in e ...

. Capital was in short supply and necessary for development, including investment in monastic construction and allowing aristocrats to pay heavy taxes to the crown, so Jewish loans played an important economic role, although they were also used to finance consumption, particularly among overstretched, landholding Knights.

The Church's highest authority, the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

, had placed restrictions on the mixing of Jews with Christians, and at the Fourth Lateran Council

The Fourth Council of the Lateran or Lateran IV was convoked by Pope Innocent III in April 1213 and opened at the Lateran Palace in Rome on 11 November 1215. Due to the great length of time between the council's convocation and its meeting, m ...

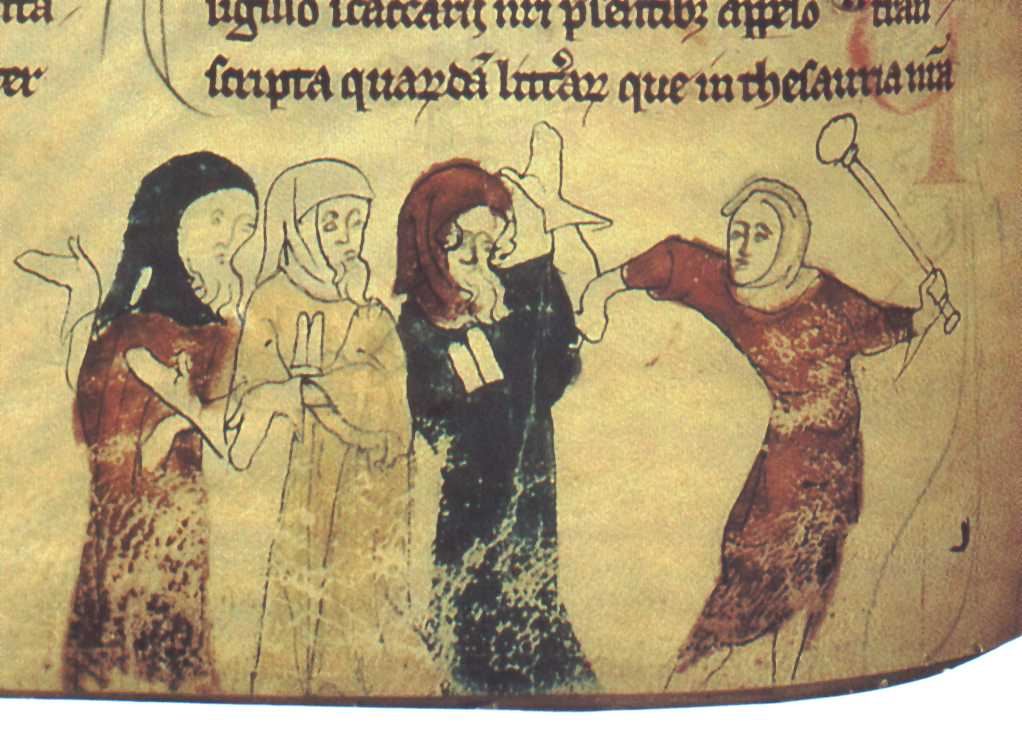

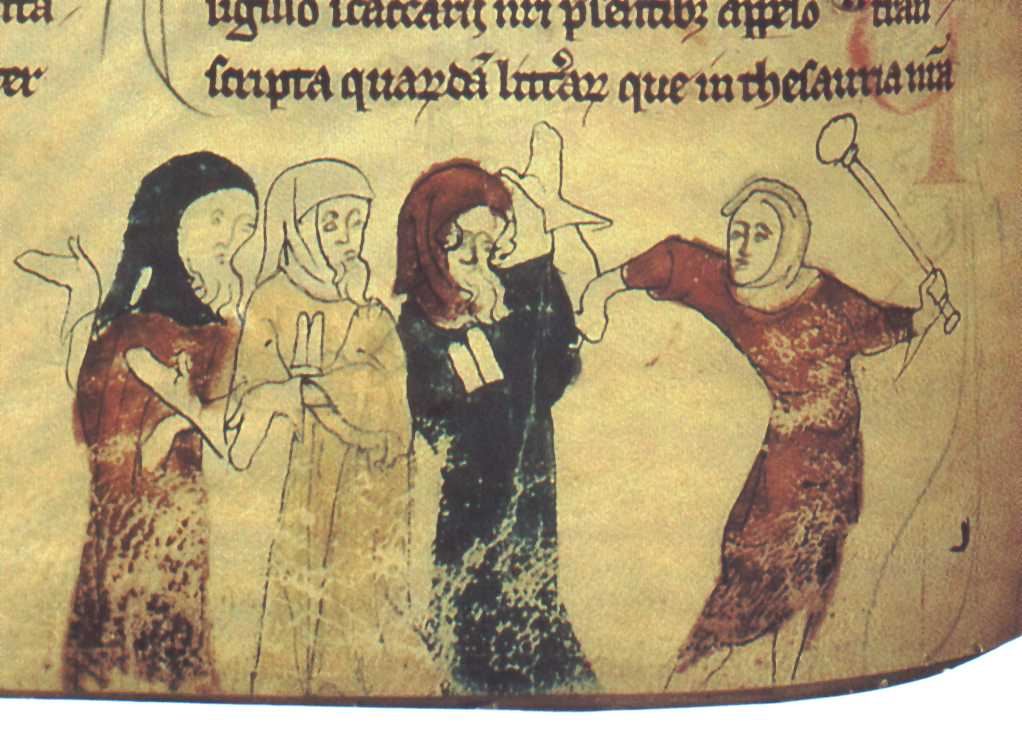

in 1215 had mandated the wearing of distinctive clothing such as or Jewish badges. These measures were adopted in England at the Synod of Oxford in 1222. Church leaders made the first allegations of ritual child sacrifice, such as crucifixions at Easter in mockery of Christ, and the accusations began to develop into themes of conspiracy and occult practices. King Henry III backed allegations made against Jews of Lincoln after the death of a boy named Hugh, who soon became known as Little Saint Hugh. Such stories coincided with the rise of hostility within the Church to the Jews.

Discontent increased after the Crown destabilised the loans and debt market. Loans were typically secured through bonds that entitled the lender to the debtor's land holdings. Interest rates were relatively high and debtors tended to be in arrears. Repayments and actual interest paid were a matter for negotiation and it was unusual for a Jewish lender to foreclose debts. As the Crown overtaxed Jews, they were forced to sell their debt bonds at reduced prices to quickly raise cash. Rich courtiers would buy the cut-price bonds, and could call in the loans and demand the lands that had secured the loans. This caused the transfer of the land wealth of indebted knights and others, especially from the 1240s, as the taxation of Jews became unsustainably high. Leaders like Simon de Montfort then used anger at the dispossession of middle-ranking landowners to fuel antisemitic violence at London, where 500 Jews died; Worcester; Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, in the county of Kent, England; it was a county borough until 1974. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour. The city has a mild oceanic climat ...

; and many other towns. In the 1270s and 1280s, Queen Eleanor amassed vast lands and properties through this process, causing widespread resentment and conflict with the Church, which viewed her acquisitions as profiting from usury. By 1275, as the result of punitive taxation, the crown had eroded the Jewish community's wealth to the extent taxes produced little return.

Steps towards expulsion

The first major step towards expulsion took place in 1275 with the Statute of the Jewry, which outlawed all lending at interest and allowed Jews to lease land, which had previously been forbidden. This right was granted for the following 15 years, supposedly giving Jews a period to readjust; this was an unrealistic expectation because entry to other trades was generally restricted.Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 125 ...

attempted to convert Jews by compelling them to listen to Christian preachers.

The Church took further action, for example John Peckham the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

campaigned to suppress seven London synagogues in 1282. In late 1286, Pope Honorius IV

Pope Honorius IV (born Giacomo Savelli; — 3 April 1287) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 April 1285 to his death on 3 April 1287. His election followed the death of Pope Martin IV and was notable for its sp ...

addressed a special letter or "rescript" to the Archbishops of York and Canterbury claiming Jews had an evil effect on religious life in England through free interaction with Christians, and calling for action to be taken to prevent it. Honorius's demands were restated at the Synod of Exeter.

Jews were targeted in the coin clipping crisis of the late 1270s, when over 300 Jews—over 10% of England's Jewish population—were sentenced to death for interfering with the currency. The Crown profited from seized assets and payments of fines by those who were not executed, raising at least £16,500. While it is unclear how impoverished the Jewish community was in these last years, historian Henry Richardson notes Edward did not impose any further taxation from 1278 until the late 1280s. It appears some Jewish moneylenders continued to lend money against future delivery of goods to avoid usury restrictions, a practice that was wholly known to the Crown because debts had to be recorded in a government ' or chest where debts were recorded. Others found ways to continue trading and it is likely others left the country.

Expulsion of the Jews from Gascony

Local or temporary expulsions of Jews had taken place in other parts of Europe, and regularly in England. For example, Simon de Montfort expelled the Jews ofLeicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area, and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest city in the East Midlands with a popula ...

in 1231, and in 1275, Edward I had permitted the Queen mother Eleanor to expel Jews from her lands and towns.

In 1287, Edward I was in his French provinces in the Duchy of Gascony

The Duchy of Gascony or Duchy of Vasconia was a duchy located in present-day southwestern France and northeastern Spain, an area encompassing the modern region of Gascony. The Duchy of Gascony, then known as ''Wasconia'', was originally a Franki ...

while trying to negotiate the release of his cousin Charles of Salerno, who was being held captive in Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and ; ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces of Spain, ...

. On Easter Sunday, Edward broke his collarbone in an fall, and was confined to bed for several months. Soon after his recovery, Edward ordered the expulsion of local Jews from Gascony. His immediate motivation may have been the need to generate funds for Charles' release, but many historians, including Richard Huscroft, have said the money raised by seizures from exiled Jews was negligible and that it was given away to mendicant orders

Mendicant orders are primarily certain Catholic Church, Catholic religious orders that have vowed for their male members a lifestyle of vow of poverty, poverty, traveling, and living in urban areas for purposes of preacher, preaching, Evangelis ...

(i.e. friars), and therefore see the expulsion as a "thank-offering" for Edward's recovery from his injury.

After his release, in 1289, Charles of Salerno expelled Jews from his territories in Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

and Anjou, accusing them of "dwelling randomly" with the Christian population and cohabiting with Christian women. He linked the expulsion to general taxation of the population as "recompense" for lost income. Edward and Charles may have learnt from each other's experience.

Expulsion

By the time he returned to England from Gascony in 1289, Edward I was deeply in debt. At the same time, his experiment to convert the Jews to Christianity and remove their dependence on lending at interest had failed; the fifteen-year period in which Jews were allowed to lease farms had ended. Also, raising significant sums of money from the Jewish population had become increasingly difficult because they had been repeatedly overtaxed. In 14 June 1290, Edward summoned representatives of the knights of the shires, the middling landowners, to attend Parliament by 15 July. These knights were the group that was most hostile to Jews and usury. On 18 June, Edward sent secret orders to the sheriffs of cities with Jewish residents to seal the ' containing records of Jewish debts. The reason for this is disputed; it could represent preparation for a further tallage to be paid by the Jewish population or it could represent a preparatory step for expulsion. Parliament met on 15 July; there is no record of the Parliamentary debates so it is uncertain whether the Crown offered the Expulsion of the Jews in return for a vote of taxation or whether Parliament asked for it as a concession. Both views are argued. The link between these seems certain given the evidence of contemporaneous chronicles and the speed at which orders to expel the Jews of England were made, possibly after an agreement was reached. The taxation granted by Parliament to Edward was very high; at £116,000 it was probably the highest of the Middle Ages. In gratitude, the Church later voluntarily agreed to pay tax of a tenth of its revenue. On 18 July, the Edict of Expulsion was issued. The text of the edict is lost. On theHebrew calendar

The Hebrew calendar (), also called the Jewish calendar, is a lunisolar calendar used today for Jewish religious observance and as an official calendar of Israel. It determines the dates of Jewish holidays and other rituals, such as '' yahrze ...

, 18 July of that year was 9 Av (Tisha B'Av

Tisha B'Av ( ; , ) is an annual fast day in Judaism. A commemoration of a number of disasters in Jewish history, primarily the destruction of both Solomon's Temple by the Neo-Babylonian Empire and the Second Temple by the Roman Empire in Jerusal ...

) 5050, commemorating the fall of the Temple at Jerusalem; it is unlikely to be a coincidence. According to Roth, it was noted "with awe" by Jewish chroniclers. On the same day, writs were sent to sheriffs saying all Jews were to leave by All Saints' Day

All Saints' Day, also known as All Hallows' Day, the Feast of All Saints, the Feast of All Hallows, the Solemnity of All Saints, and Hallowmas, is a Christian solemnity celebrated in honour of all the saints of the Church, whether they are know ...

, 1 November 1290, and outlining their duties in the matter.

The edict was implemented with some attempt at fairness. Proclamations ordering the population not to "injure, harm, damage or grieve" the departing Jews were made. Wardens at the Cinque Ports

The confederation of Cinque Ports ( ) is a historic group of coastal towns in south-east England – predominantly in Kent and Sussex, with one outlier (Brightlingsea) in Essex. The name is Old French, meaning "five harbours", and alludes to ...

were told to make arrangements for the Jews' safe passage and cheap fares for the poor, while safe conduct was arranged for dignitaries, such as the wealthy financier Bonamy of York. There were limits on the property Jews could take with them. Although a few favoured persons were allowed to sell their homes before they left, the vast majority had to forfeit any outstanding debts, homes and immobile property, including synagogues and cemeteries.

On 5 November, Edward wrote to the Barons of the Exchequer

The Barons of the Exchequer, or ''barones scaccarii'', were the judges of the English court known as the Exchequer of Pleas. The Barons consisted of a Chief Baron of the Exchequer and several puisne (''inferior'') barons. When Robert Shute was a ...

, giving the clearest-known official explanation of his actions. In it, Edward said the Jews had broken trust with him by continuing to find ways to charge interest on loans. He labelled them criminals and traitors, and said they had been expelled "in honour of the Crucified esus

Esus is a Celtic god known from iconographic, epigraphic, and literary sources.

The 1st-century CE Roman poet Lucan's epic ''Pharsalia'' mentions Esus, Taranis, and Teutates as gods to whom the Gauls sacrificed humans. This rare mention of Cel ...

. Interest to be paid on debts seized by the Crown was to be cancelled.

The Jewish refugees

The Jewish population in England at the time of the expulsion was relatively small, perhaps as few as 2,000 people, although estimates vary. Decades of privations had caused many Jews to emigrate or convert. Although it is believed most of the Jews were able to leave England in safety, there are some records of piracy leading to the death of some expelled Jews. On 10 October, a ship of poor London Jews had chartered, which a chronicler described as "bearing their scrolls of the law", sailed toward the mouth of theThames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after th ...

near Queenborough ''en route'' to France. While the tide was low, the captain persuaded the Jews to walk with him on a sandbank; as the tide rose, he returned to the ship, telling the Jews to call upon Moses for help. It appears those involved in this incident were punished. Another incident occurred in Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

, where sailors received a pardon in 1294, and a ship is recorded as drifting ashore near Burnham-on-Crouch

Burnham-on-Crouch is a town and civil parish in the Maldon District of Essex, in the East of England; it lies on the north bank of the River Crouch. It is one of Britain's leading places for yachting.

The civil parish extends east of the town ...

, Essex, the Jewish passengers having been robbed and murdered. The condition of the sea in autumn was also dangerous; around 1,300 poor Jewish passengers crossed the English Channel to Wissant near Calais for 4deach. Tolls were collected by the constable of the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

from those leaving on their departure, of 4d or 2d for "poor Jews". Some ships were lost at sea and others arrived with their passengers destitute.

It is unclear where most of the migrants went. Those arriving in France were initially allowed to stay in Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; , or ) is a city and Communes of France, commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme (department), Somme Departments of France, department in the region ...

and Carcassonne

Carcassonne is a French defensive wall, fortified city in the Departments of France, department of Aude, Regions of France, region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania. It is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the department.

...

but permission was soon revoked. Because most of the Anglo-Jewry still spoke French, historian Cecil Roth

Cecil Roth (5 March 1899 – 21 June 1970) was an English historian.

He was editor-in-chief of the ''Encyclopaedia Judaica''.

Life

Roth was born in Dalston, London, on 5 March 1899. His parents were Etty and Joseph Roth, and Cecil was the younge ...

speculates most would have found refuge in France. Evidence from personal names in records show some Jews with the appellation "L'Englesche" or "L'Englois" (ie, ''the English'') in Paris, Savoy and elsewhere. Similar names can be found among the Spanish Jewry, and the Venetian Clerli family claimed descent from Anglo-Jewish refugees. The locations where Anglo-Jewish texts have been found is also evidence for the possible destination of migrants, including places in Germany, Italy, and Spain. The title deeds to an English monastery have been found in the wood store of a synagogue in Cairo, where according to Roth, a refugee from England deposited the document. In the rare case of Bonamy of York, there is a record of him accidentally meeting creditors in Paris in 1292. Other individual cases can be speculated about, such as that of Licoricia of Winchester's sons Asher and Lumbard, and her grandchildren, who were likely among the exiles.

Disposal of Jewish property

Following the expulsion, the Crown seized Jewish property. Debts with a value of £20,000 were collated from the ' from each town with a Jewish settlement. In December, Hugh of Kendall was appointed to dispose of the property seized from the Jewish refugees, the most-valuable of which consisted of houses in London. Some of the property was given away to courtiers, the Church and the royal family's circle in a total of 85 grants. William Burnell received property in

Following the expulsion, the Crown seized Jewish property. Debts with a value of £20,000 were collated from the ' from each town with a Jewish settlement. In December, Hugh of Kendall was appointed to dispose of the property seized from the Jewish refugees, the most-valuable of which consisted of houses in London. Some of the property was given away to courtiers, the Church and the royal family's circle in a total of 85 grants. William Burnell received property in Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

which he later gave to Balliol College

Balliol College () is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1263 by nobleman John I de Balliol, it has a claim to be the oldest college in Oxford and the English-speaking world.

With a governing body of a master and ar ...

; for example, Queen Eleanor's tailor was granted the synagogue in Canterbury. Sales were mostly completed by early 1291 and around £2,000 was raised, £100 of which was used to glaze windows and decorate the tomb of Henry III in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

. It appears there was no systematic attempt to collect the £20,000 worth of seized debts. The reasons for this could include the death of Queen Eleanor in November 1290, concerns over a possible war with Scotland, or an attempt to win political favour by providing benefit to those previously indebted.

After the Expulsion

Jewish presence in England after the Expulsion

It is likely the few Jews remaining in England after the expulsion were converts. At the time of the expulsion, there were around 100 converted Jews in the , which provided accommodation to Jews who had converted to Christianity. The last of the pre-1290 converts Claricia, the daughter of Jacob Copin, died in 1356, having spent the early part of the 1300s inExeter

Exeter ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and the county town of Devon in South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter w ...

, where she raised a family. Between the Expulsion of the Jews in 1290 and their informal return in 1655, there continue to be records of Jews in the up to and after 1551. The expulsion is unlikely to have been wholly enforceable. Four complaints were made to the king in 1376 that some of those trading as Lombards

The Lombards () or Longobards () were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written betwee ...

were actually Jews.

Propagandising the Expulsion

After the expulsion, Edward I sought to position himself as the defender of Christians against the supposed criminality of Jews. Most prominently, he continued personal veneration ofLittle Saint Hugh of Lincoln

Hugh of Lincoln (1246 – 27 August 1255) was an English boy whose death in Lincoln, England, Lincoln was blood libel, falsely attributed to Jews. He is sometimes known as Little Saint Hugh or Little Sir Hugh to distinguish him from the adu ...

, a child who whose death had been falsely attributed to ritual murder by Jews. After the death of his wife Queen Eleanor in late 1290, Edward reconstructed the shrine, incorporating the Royal Coat of Arms, in the same style as the Eleanor crosses. It appears to have been an attempt by Edward to associate himself and Eleanor with the cult. According to historian Joe Hillaby, this "propaganda coup" boosted the circulation of the Saint Hugh myth, the most famous of the English blood libels, which is repeated in literature and the " Sir Hugh" folk songs into the twentieth century. Other efforts to justify the expulsion can be found in the Church, for instance in the canonisation evidence submitted for Thomas de Cantilupe

Thomas de Cantilupe (25 August 1282; also spelled ''Cantelow, Cantelou, Canteloupe'', List of Latinised names, Latinised to ''de Cantilupo'') was Lord Chancellor, Lord Chancellor of England and Bishop of Hereford. He was canonised in 1320 by P ...

, and on the Hereford ''Mappa Mundi''.

Significance

The permanent expulsion of Jews from England and tactics employed before it, such as attempts at forced conversion, are widely seen as setting a significant precedent and an example for the 1492

The permanent expulsion of Jews from England and tactics employed before it, such as attempts at forced conversion, are widely seen as setting a significant precedent and an example for the 1492 Alhambra Decree

The Alhambra Decree (also known as the Edict of Expulsion; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Decreto de la Alhambra'', ''Edicto de Granada'') was an edict issued on 31 March 1492 by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdi ...

. Traditional narratives of Edward I have sought to downplay the event, emphasising the peacefulness of the expulsion or placing its roots in Edward's pragmatic need to extract money from Parliament; more recent work on the Anglo-Jewish community's experience have framed it as the culmination of a policy of state-sponsored antisemitism. These studies place the expulsion in the context of the execution of Jews for coin clipping and the first royal-sponsored attempts at converting Jews to Christianity, saying this was the first time a state had permanently expelled all Jews from its territory.

For Edward I's contemporaries, there is evidence the expulsion was seen as one of his most-prominent achievements. It was named alongside his wars of conquest in Scotland and Wales in the '' Commendatio'' that was widely circulated after his death, saying Edward I outshone the Pharoahs by exiling the Jews.

The expulsion had a lasting effect on medieval and early-modern English culture. Antisemitic narratives became embedded in the idea of England as unique because it had no Jews, and of the English as God's chosen people, superseding the Jews. Jews became an easy target of literature and plays, and tropes such as child sacrifice and host desecration persisted. Jews began to settle in England after 1656, and formal equality was achieved by 1858. According to medieval historian Colin Richmond, English antisemitism left a legacy of neglect of this topic in English historical research as late as the 1990s. The story of Little Saint Hugh was repeated as fact in local guidebooks in Lincoln in the 1920s, and a private school was named after Hugh around the same time. The logo of the school, which referenced the story, was altered in 2020.

Apology

In May 2022, theChurch of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

held a service that the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby

Justin Portal Welby (born 6 January 1956) is an Anglican bishop who served as the 105th archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England from 2013 to 2025.

After an 11-year career in the oil industry, Welby trained for ordination at St John ...

described as a formal "act of repentance" on the 800th anniversary of the Synod of Oxford in 1222. The Synod passed a set of laws that restricted the right of Jews in England to engage with Christians, which directly contributed to the expulsion of 1290.,

See also

*Alhambra Decree

The Alhambra Decree (also known as the Edict of Expulsion; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Decreto de la Alhambra'', ''Edicto de Granada'') was an edict issued on 31 March 1492 by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdi ...

* Expulsion of the Moriscos

* Robert de Reddinge

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *: * * * * * * * *: * * * * * *: *: * * * * *External links

When England Expelled the Jews

by Rabbi Menachem Levine, Aish.com

England related articles

in ''

The Jewish Encyclopedia

''The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day'' is an English-language encyclopedia containing over 15,000 articles on the ...

''

National Archive educational resource on the Expulsion

{{DEFAULTSORT:Edict Of Expulsion 1290 in England 1290s in law 13th-century Judaism Antisemitism in England Expulsion Edward I of England Expulsions of Jews Jewish English history Medieval Jewish history Religious expulsion orders Sephardi Jews topics Ethnic cleansing in Europe