Ed Brooke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

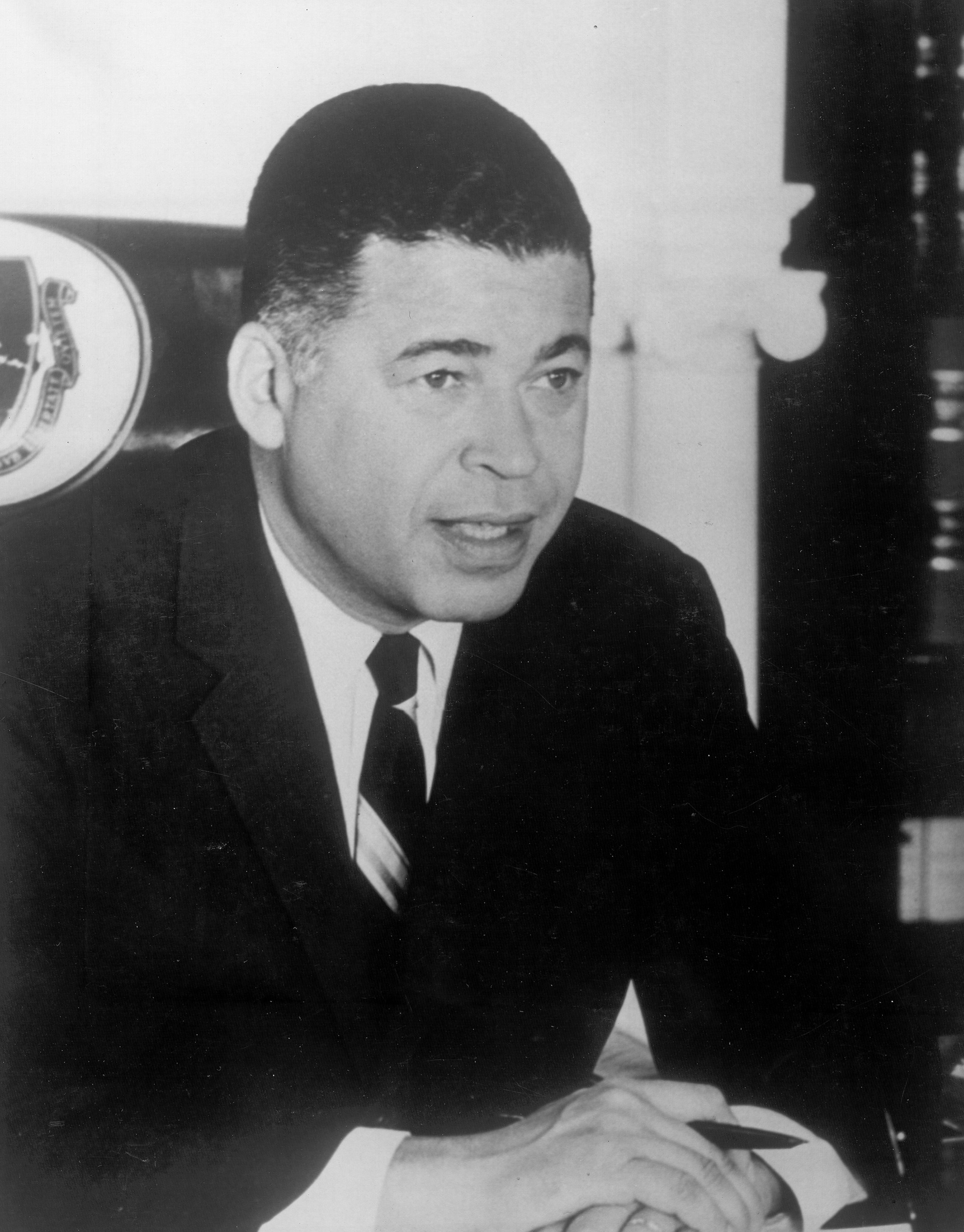

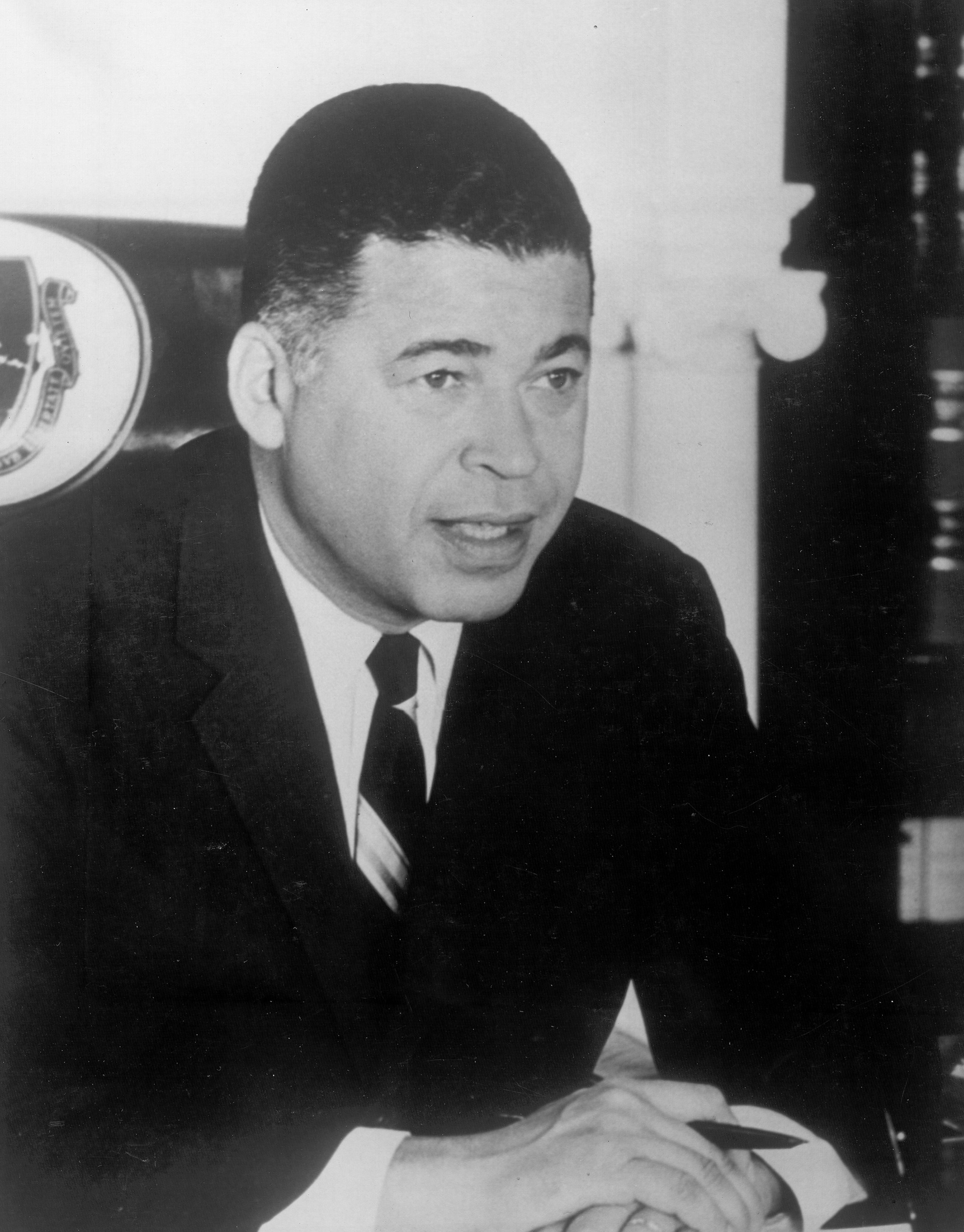

Edward William Brooke III (October 26, 1919 – January 3, 2015) was an American lawyer and Republican Party politician who represented

Despite losing the secretary's race to White, the closeness of the results led to Republican leaders taking notice of Brooke's potential. Governor

Despite losing the secretary's race to White, the closeness of the results led to Republican leaders taking notice of Brooke's potential. Governor

At the November 8, 1966, Massachusetts Senate election, Brooke defeated former

At the November 8, 1966, Massachusetts Senate election, Brooke defeated former

Ghostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

Then student government president

In 1975, with the extension and expansion of the

In 1975, with the extension and expansion of the

After leaving the Senate, Brooke practiced law in Washington, D.C., first as a partner at the Washington firm of O'Connor & Hannan; later of counsel to Csaplar & Bok in Boston.

He also served as chairman of the board of the

After leaving the Senate, Brooke practiced law in Washington, D.C., first as a partner at the Washington firm of O'Connor & Hannan; later of counsel to Csaplar & Bok in Boston.

He also served as chairman of the board of the

Goldwaterism Triumphant?: Race and the Debate Among Republicans over the Direction of the GOP, 1964–1968

" Paper presented at the 2006 Conference of the Historical Society, Chapel Hill, NC. * Barbara Walters (2008), ''Audition: A Memoir''. Random House. . * Edward Brooke (1966), ''The Challenge of Change: Crisis in our Two-Party System''. Little, Brown, Boston.

Edward Brooke's oral history video excerpts

at The National Visionary Leadership Project * * , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Brooke, Edward William III 1919 births 2015 deaths African-American people in Massachusetts politics African-American United States senators African-American Episcopalians United States Army personnel of World War II Boston University School of Law alumni Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Congressional Gold Medal recipients Howard University alumni Massachusetts attorneys general Massachusetts Republicans Military personnel from Washington, D.C. Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Republican Party United States senators from Massachusetts United States Army officers Dunbar High School (Washington, D.C.) alumni 20th-century American Episcopalians African Americans in World War II African-American United States Army personnel Boston Finance Commission members African-American candidates for the United States Senate 20th-century African-American politicians 20th-century Massachusetts politicians 20th-century American lawyers 20th-century African-American lawyers 20th-century United States senators

Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

from 1967 to 1979. He was the first African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

elected to the United States Senate by popular vote. Prior to serving in the Senate, he served as the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts from 1963 until 1967. Edward Brooke was the first African-American since Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

in 1874 to have been elected to the United States Senate and he was the first African-American since 1881 to have held a United States Senate seat. Brooke was also the first African-American U.S. senator to ever be re-elected. He was the longest-serving African-American U.S. senator until surpassed by Tim Scott

Timothy Eugene Scott (born September 19, 1965) is an American businessman and politician serving since 2013 as the Seniority in the United States Senate, junior United States Senate, United States senator from South Carolina. A member of the Re ...

in 2025.

Born to a middle-class black family, Brooke was raised in Washington, D.C. After attending Howard University

Howard University is a private, historically black, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and accredited by the Mid ...

, he graduated from Boston University School of Law

The Boston University School of Law (BU Law) is the law school of Boston University, a private research university in Boston. Established in 1872, it is the third-oldest law school in New England, after Harvard Law School and Yale Law School. Ap ...

in 1948 after serving in the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Beginning in 1950, he became involved in politics, when he ran for a seat in the Massachusetts House of Representatives

The Massachusetts House of Representatives is the lower house of the Massachusetts General Court, the State legislature (United States), state legislature of Massachusetts. It is composed of 160 members elected from 14 counties each divided into ...

. After serving as chairman of the Boston Finance Commission The Boston Finance Commission (known as FinComm) is an agency that monitors finances for the city of Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The ...

, Brooke was elected attorney general in 1962

The year saw the Cuban Missile Crisis, which is often considered the closest the world came to a Nuclear warfare, nuclear confrontation during the Cold War.

Events January

* January 1 – Samoa, Western Samoa becomes independent from Ne ...

, becoming the first African-American to be elected attorney general of any state.

He served as attorney general for four years, before running for Senate in 1966

Events January

* January 1 – In a coup, Colonel Jean-Bédel Bokassa takes over as military ruler of the Central African Republic, ousting President David Dacko.

* January 3 – 1966 Upper Voltan coup d'état: President Maurice Yaméogo i ...

. In the election, he defeated Democratic former Governor Endicott Peabody

Endicott Howard Peabody (February 15, 1920 – December 2, 1997) was an American politician from Massachusetts. A Democrat, he served a single two-year term as the 62nd Governor of Massachusetts, from 1963 to 1965. His tenure is probably ...

in a landslide, and was seated on January 3, 1967. In the Senate, Brooke aligned with the liberal faction in the Republican party. He co-wrote the Civil Rights Act of 1968

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 () is a Lists of landmark court decisions, landmark law in the United States signed into law by President of the United States, United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during the King assassination riots.

Titles ...

, which prohibited housing discrimination

Housing discrimination refers to patterns of discrimination that affect a person's ability to rent or buy housing. This disparate treatment of a person on the housing market can be based on group characteristics or on the place where a person liv ...

. He was re-elected to a second term in 1972

Within the context of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) it was the longest year ever, as two leap seconds were added during this 366-day year, an event which has not since been repeated. (If its start and end are defined using Solar time, ...

, after defeating attorney John Droney. Brooke became a prominent critic of Republican President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

, and was the first Senate Republican to call for Nixon's resignation in light of the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the Presidency of Richard Nixon, administration of President Richard Nixon. The scandal began in 1972 and ultimately led to Resignation of Richard Nixon, Nix ...

. In 1978

Events January

* January 1 – Air India Flight 855, a Boeing 747 passenger jet, crashes off the coast of Bombay, killing 213.

* January 5 – Bülent Ecevit, of Republican People's Party, CHP, forms the new government of Turkey (42nd ...

, he ran for a third term, but was defeated by Democrat Paul Tsongas

Paul Efthemios Tsongas ( ; February 14, 1941 – January 18, 1997) was an American politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1979 until 1985 and in the United States House of Representatives from 1975 until 1 ...

. After leaving the Senate, Brooke practiced law in Washington, D.C., and was affiliated with various businesses and nonprofit organizations. Brooke died in 2015, at his home in Coral Gables, Florida

Coral Gables is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. The city is part of the Miami metropolitan area of South Florida and is located southwest of Greater Downtown Miami, Downtown Miami. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 ...

, at the age of 95, and was the last living former U.S. senator born in the 1910s.

Early life and education

Edward William Brooke III was born on October 26, 1919, inWashington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, to a middle-class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

black family. His father Edward William Brooke Jr. was a lawyer and graduate of Howard University

Howard University is a private, historically black, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and accredited by the Mid ...

who worked with the Department of Veterans Affairs

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is a Cabinet-level executive branch department of the federal government charged with providing lifelong healthcare services to eligible military veterans at the 170 VA medical centers an ...

, and his mother was Helen (née Seldon) Brooke. He was the second of three children. Brooke was raised in a racially segregated

Racial segregation is the separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, such as schools and hospitals by people ...

environment that was "insulated from the harsh realities of the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

", with Brooke rarely interacting with the white community. He attended Dunbar High School—then one of the most prestigious academic high schools for African Americans—and graduated in 1936. After graduating, he enrolled in Howard University, where he first considered studying in medicine, before ending up studying social studies and political science. Brooke graduated from university in 1941, with a bachelor of science degree, After serving in the U.S. Army during World War II, Brooke graduated from the Boston University School of Law

The Boston University School of Law (BU Law) is the law school of Boston University, a private research university in Boston. Established in 1872, it is the third-oldest law school in New England, after Harvard Law School and Yale Law School. Ap ...

in 1948. "I never studied much at Howard," he later reflected, "but at Boston University, I didn't do much else but study."

Military service

Brooke enlisted in theUnited States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

in 1941 following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant. He saw combat in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

as a member of the segregated 366th Infantry Regiment. Brooke spent 195 days with his unit in Italy. There, his fluent Italian and his light skin enabled him to cross enemy lines to communicate with Italian partisans

The Italian Resistance ( ), or simply ''La'' , consisted of all the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social Republic during the Second World War in Italy ...

. By the end of the war, Brooke had attained the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

, a Bronze Star Medal

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious a ...

, and a Distinguished Service Award.

Brooke's time in the army exposed him to the inequality and racism which existed in the army system. This, combined with the signing of Executive Order 9066

Executive Order 9066 was a President of the United States, United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. "This order authorized the fo ...

, led him to rethink his support of Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

. His time in the army also changed his perception of race, with him meeting his future-wife Remigia Ferrari-Scacco in Italy. He reasoned that "race had not mattered during our courtship in Italy, and therefore it should not have mattered in the United States".

Early career

After graduating from Boston University, Brooke worked as a lawyer. He declined offers to join established law firms, instead opening his own law practice in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston.Politics

Brooke began his foray in politics in 1950, when, at the urging of friends from his former army unit, Brooke ran for a seat in theMassachusetts House of Representatives

The Massachusetts House of Representatives is the lower house of the Massachusetts General Court, the State legislature (United States), state legislature of Massachusetts. It is composed of 160 members elected from 14 counties each divided into ...

. Brooke didn't affiliate with both of the major parties, choosing instead to run in both the Democratic and Republican primaries. He won the Republican nomination, and was endorsed by the party, but lost the general election in a landslide to his Democratic opponent. Two years later, he ran again for the same seat, but again lost the election to the same Democratic opponent. In 1960

It is also known as the "Year of Africa" because of major events—particularly the independence of seventeen African nations—that focused global attention on the continent and intensified feelings of Pan-Africanism.

Events January

* Janu ...

, Brooke ran for secretary of state (which, in Massachusetts, is styled "Secretary of the Commonwealth"); he won the Republican nomination, becoming the first black person to be nominated for statewide office in Massachusetts. However, he lost the election to future mayor of Boston Kevin White, whose campaign issued a bumper sticker

A bumper sticker is an adhesive label or sticker designed to be attached to the rear of a car or truck, often on the bumper. They are commonly sized at around and are typically made of PVC.

Bumper stickers serve various purposes, including p ...

saying, "Vote White," which some took as a reference to Brooke's race.  Despite losing the secretary's race to White, the closeness of the results led to Republican leaders taking notice of Brooke's potential. Governor

Despite losing the secretary's race to White, the closeness of the results led to Republican leaders taking notice of Brooke's potential. Governor John Volpe

John Anthony Volpe ( ; December 8, 1908November 11, 1994) was an American businessman, diplomat, and politician from Massachusetts. A son of Italian immigrants, he founded and owned a large construction firm. Politically, he was a Republican in ...

sought to reward Brooke for his efforts, and offered him a number of jobs, most of them judicial in nature. Seeking a position with a higher political profile, Brooke eventually accepted the position of Finance Commission of Boston, where he investigated financial irregularities and uncovered evidence of corruption in city affairs. He was described in the press as having "the tenacity of a terrier

Terrier () is a Dog type, type of dog originally bred to hunt vermin. A terrier is a dog of any one of many Dog breed, breeds or landraces of the terrier Dog type, type, which are typically small, wiry, Gameness, game, and fearless. There are fi ...

", and it was reported that he "restore to vigorous life an agency which many had thought moribund." He parlayed his achievements into a successful election as Attorney General of Massachusetts

The Massachusetts attorney general is an elected Constitution of Massachusetts, constitutionally defined executive officer of the Massachusetts government. The officeholder is the chief lawyer and law enforcement officer of the Massachusetts, Com ...

in 1962

The year saw the Cuban Missile Crisis, which is often considered the closest the world came to a Nuclear warfare, nuclear confrontation during the Cold War.

Events January

* January 1 – Samoa, Western Samoa becomes independent from Ne ...

, becoming the first African-American to be elected attorney general of any state.

As attorney general, Brooke gained a reputation as a vigorous prosecutor of organized crime

Organized crime is a category of transnational organized crime, transnational, national, or local group of centralized enterprises run to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally thought of as a f ...

and corruption, securing convictions against a number of members of the administration of governor Foster Furcolo

John Foster Furcolo (July 29, 1911 – July 5, 1995) was an American lawyer, writer, and Democratic Party politician from Massachusetts. He was the state's 60th governor, and also represented the state as a member of the United States House o ...

; an indictment against Furcolo was dismissed due to lack of evidence. He also coordinated with local police departments on the Boston Strangler

The Boston Strangler is the name given to the murderer of 13 women in Greater Boston during the early 1960s. The crimes were attributed to Albert DeSalvo based on his confession, on details revealed in court during a separate case, and DNA profi ...

case, although the press mocked him for permitting an alleged psychic

A psychic is a person who claims to use powers rooted in parapsychology, such as extrasensory perception (ESP), to identify information hidden from the normal senses, particularly involving telepathy or clairvoyance; or who performs acts that a ...

to participate in the investigation. In 1964, following the nomination of Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and major general in the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve who served as a United States senator from 1953 to 1965 and 1969 to 1987, and was the Re ...

as the Republican party's nominee for president, Brooke found Goldwater's nomination offensive. He publicly broke with the party, and implored Republicans "not to invest in the 'pseudo-conservatism' of zealots". His public repudiation of Goldwater actually helped Brooke win re-election in 1964

Events January

* January 1 – The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland is dissolved.

* January 5 – In the first meeting between leaders of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches since the fifteenth century, Pope Paul VI and Patria ...

, as he won by a plurality of nearly 800,000. Encouraged by an outpour of positive support, Brooke continued to offer blunt criticisms of the Republicans, though he began softening his rhetoric by proposing strategies to rebuild the Republican party. This included an off-year national convention to "hammer out an agreement for the future of the party" and "draft a responsible platform to address bread-and-butter issues". By 1965, Brooke had emerged as the main Republican spokesman for racial equality, despite "never rallying his race to challenge segregation barriers with the inspirational fervor of a Martin Luther King

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights movement from 1955 until his a ...

."

U.S. Senate

First term (1967–1973)

At the November 8, 1966, Massachusetts Senate election, Brooke defeated former

At the November 8, 1966, Massachusetts Senate election, Brooke defeated former Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

Endicott Peabody

Endicott Howard Peabody (February 15, 1920 – December 2, 1997) was an American politician from Massachusetts. A Democrat, he served a single two-year term as the 62nd Governor of Massachusetts, from 1963 to 1965. His tenure is probably ...

with 1,213,473 votes to Peabody's 744,761, and served as a United States senator

The United States Senate consists of 100 members, two from each of the 50 U.S. state, states. This list includes all senators serving in the 119th United States Congress.

Party affiliation

Independent Senators Angus King of Maine and Berni ...

for two terms, from January 3, 1967, to January 3, 1979. The black vote had, ''Time'' wrote, "no measurable bearing" on the election as less than 3% of the state's population was black, and Peabody also supported civil rights for blacks. Brooke said, "I do not intend to be a national leader of the Negro people", and the magazine said that he "condemned both Stokely Carmichael

Kwame Ture (; born Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael; June 29, 1941November 15, 1998) was an American activist who played a major role in the civil rights movement in the United States and the global pan-African movement. Born in Trini ...

and Georgia's Lester Maddox

Lester Garfield Maddox Sr. (September 30, 1915 – June 25, 2003) was an American politician who served as the 75th governor of Georgia from 1967 to 1971.

A populist Southern Democrat, Maddox came to prominence as a staunch segregationist, when ...

" as extremists; his historic election nonetheless gave Brooke "a 50-state constituency", the magazine wrote, "a power base that no other Senator can claim".

Brooke said "In all my years in the Senate, I never encountered an overt act of hostility". He recalled visiting the swimming pool at the Russell Senate Office Building

The Russell Senate Office Building is the oldest of the United States Senate office buildings. Designed in the Beaux-Arts architectural style, it was built from 1903 to 1908 and opened in 1909. It was named for former Senator Richard Russel ...

, where segregationists John C. Stennis

John Cornelius Stennis (August 3, 1901 – April 23, 1995) was an American politician who served as a U.S. senator from the state of Mississippi. He was a Democrat who served in the Senate for over 41 years, becoming its most senior member f ...

, John Little McClellan

John Little McClellan (February 25, 1896 – November 28, 1977) was an American lawyer and segregationist politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a U.S. Representative (1935–1939) and a U.S. Senator (1943–1977) from ...

, and Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902 – June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Before his 49 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South ...

invited the new senator to join them in the water. "There was no hesitation or ill will that I could see. Yet these were men who consistently voted against legislation that would have provided equal opportunity to others of my race ... it was increasingly evident that some members of the Senate played on bigotry purely for political gain".

Tenure

A member of the moderate-to-liberal Northeastern wing of the Republican Party, Brooke organized the Senate's "Wednesday Club" of progressive Republicans who met for Wednesday lunches and strategy discussions. Brooke, who supportedMichigan Governor

The governor of Michigan is the head of government of the U.S. state of Michigan. The current governor is Gretchen Whitmer, a member of the Democratic Party, who was inaugurated on January 1, 2019, as the state's 49th governor. She was re-elect ...

George W. Romney

George Wilcken Romney (July 8, 1907 – July 26, 1995) was an American businessman and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as chairman and president of American Motors Corporation from 1954 to 1962, the 43rd gove ...

and New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich "Rocky" Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979) was the 41st vice president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford. He was also the 49th governor of New York, serving from 1959 to 197 ...

's bids for the 1968 GOP presidential nomination against Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

's, often differed with President Nixon on matters of social policy and civil rights. In 1967, Brooke was awarded the Spingarn Medal

The Spingarn Medal is awarded annually by the NAACP, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for an outstanding achievement by an African Americans, African American. The award was created in 1914 by Joel Elias Spingarn, ...

from the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

.

In 1967, Brooke went to Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

on a three-week trip as a fact-finding mission. During his first formal speech in the Senate following the trip, he reversed his previous position on the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

that increased negotiations with the North Vietnamese rather than an escalation of the fighting were needed. He began to favor President Johnson's "patient" approach to Vietnam as he had been convinced that "the enemy is not disposed to participate in any meaningful negotiations".

By his second year in the Senate, Brooke had taken his place as a leading advocate against discrimination in housing and on behalf of affordable housing. With Walter Mondale

Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale (January 5, 1928April 19, 2021) was the 42nd vice president of the United States serving from 1977 to 1981 under President Jimmy Carter. He previously served as a U.S. senator from Minnesota from 1964 to 1976. ...

, a Minnesota Democrat and fellow member of the Senate Banking Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs (formerly the Committee on Banking and Currency), also known as the Senate Banking Committee, has jurisdiction over matters related to banks and banking, price controls, ...

, he co-authored the 1968 Fair Housing Act

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 () is a landmark law in the United States signed into law by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during the King assassination riots.

Titles II through VII comprise the Indian Civil Rights Act, which applie ...

, which prohibits discrimination in housing. The Act also created HUD's Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity

An office is a space where the employees of an organization perform administrative work in order to support and realize the various goals of the organization. The word "office" may also denote a position within an organization with specific du ...

as the primary enforcer of the law. President Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act into law on April 11, one week after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

Dissatisfied with the weakened enforcement provisions that emerged from the legislative process, Brooke repeatedly proposed stronger provisions during his Senate career. In 1969, Congress enacted the " Brooke Amendment" to the federal publicly assisted housing program which limited the tenants' out-of-pocket rent expenditure to 25 percent of their income. Additionally, Brooke voted in favor of the confirmation of Thurgood Marshall

Thoroughgood "Thurgood" Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme C ...

to the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

.

During the Nixon presidency, Brooke opposed repeated Administration attempts to close down the Job Corps

Job Corps is a program administered by the United States Department of Labor that offers free education and vocational training to young people ages 16 to 24.

and the Office of Economic Opportunity

The Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) was the agency responsible for administering most of the War on Poverty programs created as part of United States president Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society legislative agenda. It was established in 1964 a ...

and to weaken the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is a federal agency that was established via the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to administer and enforce civil rights laws against workplace discrimination. The EEOC investigates discrimination ...

—all foundational elements of President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

's Great Society

The Great Society was a series of domestic programs enacted by President Lyndon B. Johnson in the United States between 1964 and 1968, aimed at eliminating poverty, reducing racial injustice, and expanding social welfare in the country. Johnso ...

.

In 1969, Brooke spoke at Wellesley College

Wellesley College is a Private university, private Women's colleges in the United States, historically women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Wellesley, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1870 by Henr ...

's commencement against "coercive protest" and was understood by some students as calling protesters "elite ne'er-do-well

"Ne'er-do-well" is a derogatory term for a good-for-nothing person; or a rogue, vagrant or vagabond without means of support. It is a contraction of the phrase ''never-do-well''.

Colonial context

The term ne'er-do-well was used in the ninetee ...

s"Archived aGhostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

Then student government president

Hillary Rodham

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, lawyer and diplomat. She was the 67th United States secretary of state in the administration of Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, a U.S. senator represent ...

departed from her planned speech to rebut Brooke's words, affirming the "indispensable task of criticizing and constructive protest," for which she was featured in ''Life'' magazine.

On June 9, 1969, Brooke voted in favor of President Nixon's nomination of Warren E. Burger

Warren Earl Burger (September 17, 1907 – June 25, 1995) was an American attorney who served as the 15th chief justice of the United States from 1969 to 1986.

Born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Burger graduated from the William Mitchell College o ...

as Chief Justice of the United States

The chief justice of the United States is the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States and is the highest-ranking officer of the U.S. federal judiciary. Appointments Clause, Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution g ...

following the retirement of Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 30th governor of California from 1943 to 1953 and as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presid ...

. Brooke was a leader of the bipartisan coalition that defeated the Senate confirmation of Clement Haynsworth

Clement Furman Haynsworth Jr. (October 30, 1912 – November 22, 1989) was a United States federal judge, United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. He was also an Unsuccessful nominations to the Supr ...

, President Nixon's nominee to the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

on November 21, 1969. A few months later, he again organized sufficient Republican support to defeat Nixon's third Supreme Court nominee Harrold Carswell

George Harrold Carswell (December 22, 1919 – July 13, 1992) was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Northern Di ...

on April 8, 1970. The following month, Nixon nominee Harry Blackmun

Harold Andrew Blackmun (November 12, 1908 – March 4, 1999) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1970 to 1994. Appointed by President Richard Nixon, Blackmun ultima ...

(who later wrote the ''Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States protected the right to have an ...

'' opinion) was confirmed on May 12, 1970, with Brooke voting in favor. On December 6, 1971, Brooke voted in favor of Nixon's nomination of Lewis F. Powell Jr.

Lewis Franklin Powell Jr. (September 19, 1907 – August 25, 1998) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1972 to 1987.

Born in Suffolk, Virginia, he graduated ...

, while on December 10, Brooke voted against Nixon's nomination of William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist (October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American attorney who served as the 16th chief justice of the United States from 1986 until his death in 2005, having previously been an associate justice from 1972 to 1986. ...

as Associate Justice. On December 17, 1975, Brooke voted in favor of President Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was the 38th president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Ford assumed the p ...

's nomination of John Paul Stevens

John Paul Stevens (April 20, 1920 – July 16, 2019) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1975 to 2010. At the time of his retirement, he was the second-oldes ...

to the Supreme Court.

Second term (1973–1979)

Relations with the White House and 1972 election

Despite Brooke's disagreements with Nixon, the president reportedly respected the senator's abilities; after Nixon's election he had offered to make Brooke a member of his cabinet, or appoint him as ambassador to the UN. The press discussed Brooke as a possible replacement forSpiro Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew (; November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th vice president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second of two vice presidents to resign, the first being John C. ...

as Nixon's running mate in the 1972 presidential election. While Nixon retained Agnew, Brooke was re-elected in 1972, defeating Democrat John J. Droney

John Joseph Droney (1911–1989) was an American politician who served as district attorney of Middlesex County, Massachusetts from 1959 to 1983.

Early life

Droney was raised in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He played football and hockey at Cambrid ...

by a vote of 64%–35%. Edward Brooke was the first African American ever to have been re-elected to the United States Senate.

Tenure

Before the first year of his second term ended, Brooke became the first Republican to call on President Nixon to resign, on November 4, 1973, shortly after theWatergate

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon. The scandal began in 1972 and ultimately led to Nixon's resignation in 1974, in August of that year. It revol ...

-related "Saturday night massacre

The "Saturday Night Massacre" was a series of resignations over the dismissal of special prosecutor Archibald Cox that took place in the United States Department of Justice during the Watergate scandal in 1973. The events followed the refusal b ...

". He repeated the recommendation in a meeting with Nixon at the White House on November 13, 1973. He had risen to become the ranking Republican on the Senate Banking Committee and on two powerful Appropriations subcommittees, Labor, Health and Human Services

The United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is a cabinet-level executive branch department of the US federal government created to protect the health of the US people and providing essential human services. Its motto is "Im ...

(HHS) and Foreign Operations. From these positions, Brooke defended and strengthened the programs he supported; for example, he was a leader in enactment of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) is a United States law (codified at et seq.), enacted October 28, 1974, that makes it unlawful for any creditor to discriminate against any applicant, with respect to any aspect of a credit transaction, ...

, which ensured married women the right to establish credit in their own name.

In 1974, with Indiana senator Birch Bayh

Birch Evans Bayh Jr. (; January 22, 1928 – March 14, 2019) was an American politician. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as a member of United States Senate from 1963 to 1981. He was first elected t ...

, Brooke led the fight to retain Title IX

Title IX is a landmark federal civil rights law in the United States that was enacted as part (Title IX) of the Education Amendments of 1972. It prohibits sex-based discrimination in any school or any other education program that receiv ...

, a 1972 amendment to the Higher Education Act of 1965

The Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA) () was legislation signed into Law of the United States, United States law on November 8, 1965, as part of President Lyndon Johnson's Great Society domestic agenda. Johnson chose Texas State University (t ...

, which guarantees equal educational opportunity (including athletic participation) to girls and women. In 1975, with the extension and expansion of the

In 1975, with the extension and expansion of the Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movem ...

at stake, Brooke faced Stennis in "extended debate" and won the Senate's support for the extension. In 1976, he also took on the role of supporter of wide-scale, legalized abortion. The Appropriations bill for HHS became the battleground over this issue because it funds Medicaid

Medicaid is a government program in the United States that provides health insurance for adults and children with limited income and resources. The program is partially funded and primarily managed by U.S. state, state governments, which also h ...

. The Anti-abortion movement

Anti-abortion movements, also self-styled as pro-life movements, are involved in the abortion debate advocating against the practice of abortion and its legality. Many anti-abortion movements began as countermovements in response to the leg ...

fought, eventually successfully, to prohibit funding for abortions of low-income women insured by Medicaid. Brooke led the fight against restrictions in the Senate Appropriations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Appropriations is a standing committee of the United States Senate. It has jurisdiction over all discretionary spending legislation in the Senate.

The Senate Appropriations Committee is the largest committ ...

and in the House–Senate Conference until his defeat. The press again speculated on his possible candidacy for the Vice Presidency as Gerald Ford's running mate in 1976

Events January

* January 2 – The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights enters into force.

* January 5 – The Pol Pot regime proclaims a new constitution for Democratic Kampuchea.

* January 18 – Full diplomatic ...

, with ''Time'' calling him an "able legislator and a staunch party loyalist".

In Massachusetts, Brooke's support among Catholics weakened due to his stance on abortion. During the 1978 re-election campaign, the state's bishops spoke in opposition to his leading role.

Electoral history

Post-Senate life

After leaving the Senate, Brooke practiced law in Washington, D.C., first as a partner at the Washington firm of O'Connor & Hannan; later of counsel to Csaplar & Bok in Boston.

He also served as chairman of the board of the

After leaving the Senate, Brooke practiced law in Washington, D.C., first as a partner at the Washington firm of O'Connor & Hannan; later of counsel to Csaplar & Bok in Boston.

He also served as chairman of the board of the National Low Income Housing Coalition

The National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) is a non-profit organization dedicated to ending America's affordable housing

Affordable housing is housing which is deemed affordable to those with a household income at or below the median, ...

. In 1984 he was selected as chairman of the Boston Bank of Commerce, and one year later was named to the board of directors of Grumman

The Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, later Grumman Aerospace Corporation, was a 20th century American producer of military and civilian aircraft. Founded on December 6, 1929, by Leroy Grumman and his business partners, it merged in 19 ...

.

In 1992, a Brooke assistant stated in a plea agreement as part of an investigation into corruption at the Department of Housing and Urban Development

The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government. It administers federal housing and urban development laws. It is headed by the secretary of housing and u ...

that Brooke had falsely answered questions about whether he or the assistant had tried to improperly influence HUD officials on behalf of housing and real estate developers who had paid large consulting fees to Brooke. The HUD investigation ended with no charges being brought against Brooke.

In 1996, Brooke became the first chairman of the World Policy Council

The World Policy Council of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity is a nonprofit and nonpartisan think tank established in 1996 at Howard University to expand the fraternity's involvement in politics and social and current policy to encompass important glob ...

, a think tank

A think tank, or public policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-governme ...

of Alpha Phi Alpha

Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. () is the oldest intercollegiate List of African-American fraternities, historically African American Fraternities and sororities, fraternity. It was initially a literary and social studies club organized in the ...

, an African-American fraternity. The Council's purpose is to expand the fraternity's involvement in politics, and social and current policy to encompass international concerns. In 2006 Brooke served as the council's chairman emeritus

''Emeritus/Emerita'' () is an honorary title granted to someone who retires from a position of distinction, most commonly an academic faculty position, but is allowed to continue using the previous title, as in "professor emeritus".

In some c ...

and was honorary chairman at the Centennial Convention of Alpha Phi Alpha held in Washington, D.C.

Political positions

Edward Brooke was a self-described moderate or liberal Republican, generally referred to asRockefeller Republican

The Rockefeller Republicans were members of the United States Republican Party (GOP) in the 1930s–1970s who held moderate-to- liberal views on domestic issues, similar to those of Nelson Rockefeller, Governor of New York (1959–1973) and Vi ...

s. On social issues he was a liberal who supported civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

, women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and Entitlement (fair division), entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st c ...

, and civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties of ...

such as gay rights. On economic issues he was fiscally conservative

In American political theory, fiscal conservatism or economic conservatism is a political and economic philosophy regarding fiscal policy and fiscal responsibility with an ideological basis in capitalism, individualism, limited government, an ...

, but was pragmatic about it; he still allowed that "There are things that people can't do for themselves and therefore government must do it for them".

During the 2008 presidential election, Brooke indicated in a WBUR-FM

WBUR-FM (90.9 FM) is a public radio station located in Boston, Massachusetts, owned by Boston University. Its programming is also known as WBUR News. The station is the largest of three NPR member stations in Boston, along with WGBH and W ...

interview that he favored Democratic nominee Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

.

Awards and honors

*Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, alongside the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by decision of the president of the United States to "any person recommended to the President ...

* Congressional Gold Medal

The Congressional Gold Medal is the oldest and highest civilian award in the United States, alongside the Presidential Medal of Freedom. It is bestowed by vote of the United States Congress, signed into law by the president. The Gold Medal exp ...

, presented on October 28, 2009, two days after Brooke's 90th birthday . At his 2009 Congressional Gold Medal Acceptance speech, Brooke scolded policymakers for excessive partisan bickering.

* Bronze Star Medal

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious a ...

* Adam Clayton Powell Award (Phoenix Award) in 1979

*Jeremy Nicholson Negro Achievement Award, acknowledging his outstanding contributions to the African-American community

*The Edward W. Brooke Courthouse (dedicated June 20, 2000) in Boston; part of the Massachusetts Trial Court system and houses the Central Division of the Boston Municipal Court

The Boston Municipal Court (BMC), officially the Boston Municipal Court Department of the Trial Court, is a department of the Trial Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States. The court hears criminal, civil, mental health, restr ...

, Boston Juvenile Court, Family Court

Family courts were originally created to be a Court of Equity convened to decide matters and make orders in relation to family law, including custody of children, and could disregard certain legal requirements as long as the petitioner/plaintif ...

, and Boston Housing Court

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and financial center of New England, a region of the Northeastern United States. It has an area of and a ...

, among others.

*In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante

Molefi Kete Asante ( ; born Arthur Lee Smith Jr.; August 14, 1942) is an American philosopher who is a leading figure in the fields of African-American studies, African studies, and communication studies. He is currently a professor in the Dep ...

listed Edward Brooke on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans

''100 Greatest African Americans'' is a biographical dictionary of one hundred historically great Black Americans (in alphabetical order; that is, they are not ranked), as assessed by Temple University professor Molefi Kete Asante in 2002. A ...

.

Personal life and death

Brooke had an affair withbroadcast journalist

Broadcast journalism is the field of news and journals which are broadcast by electronic methods instead of the older methods, such as printed newspapers and posters. It works on radio (via air, cable, and Internet), television (via air, cable, ...

Barbara Walters

Barbara Jill Walters (September 25, 1929December 30, 2022) was an American broadcast journalist and television personality. Known for her interviewing ability and popularity with viewers, she appeared as a host of numerous television programs, ...

in the 1970s. Walters stated that the affair was ended to protect their careers from scandal.

Brooke went through a divorce late in his second term. His finances were investigated by the Senate, and John Kerry

John Forbes Kerry (born December 11, 1943) is an American attorney, politician, and diplomat who served as the 68th United States secretary of state from 2013 to 2017 in the Presidency of Barack Obama#Administration, administration of Barac ...

, then a prosecutor in Middlesex County, announced an investigation into statements Brooke made in the divorce case. Prosecutors eventually determined that Brooke had made false statements about his finances during the divorce, and that they were pertinent, but not material enough to have affected the outcome. Brooke was not charged with a crime, but the negative publicity cost him some support in his 1978 reelection campaign, and as a result he lost to Paul Tsongas

Paul Efthemios Tsongas ( ; February 14, 1941 – January 18, 1997) was an American politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1979 until 1985 and in the United States House of Representatives from 1975 until 1 ...

.

In September 2002, Brooke was diagnosed with breast cancer

Breast cancer is a cancer that develops from breast tissue. Signs of breast cancer may include a Breast lump, lump in the breast, a change in breast shape, dimpling of the skin, Milk-rejection sign, milk rejection, fluid coming from the nipp ...

and assumed a national role in raising awareness of the disease among men.

On January 3, 2015, Brooke died at his home in Coral Gables, Florida

Coral Gables is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. The city is part of the Miami metropolitan area of South Florida and is located southwest of Greater Downtown Miami, Downtown Miami. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 ...

, at age 95. At the time of his death, he was the last living former U.S. senator born in the 1910s. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the United States National Cemetery System, one of two maintained by the United States Army. More than 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington County, Virginia.

...

.

See also

*List of African-American firsts

African Americans are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group in the United States. The first achievements by African Americans in diverse fields have historically marked footholds, often leading to more widespread cultural chan ...

* List of African-American Republicans

The following is a list of black Republicans, past and present. This list is limited to black Americans who have worked in a direct, professional capacity in politics.

A

* Israel Abbott (1813–1887), Republican State Representative from N ...

* List of African-American United States senators

This is a list of African Americans who have served in the United States Senate. The Senate has had 14 African-American elected or appointed officeholders. Two each served during both the 19th and 20th centuries. The first was Hiram R. Revels.

...

* List of African-American United States Senate candidates

This page is a list of African-American United States Senate candidates.

Listed are those African-American candidates who achieved ballot access for a federal election. They made the primary ballot, and have votes in the election in order to qu ...

Footnotes

References

Citations

General and cited sources

* * * * * Judson L. Jeffries, ''U.S. Senator Edward W. Brooke and Governor L. Douglas Wilder Tell Political Scientists How Blacks Can Win High-Profile Statewide Office'',American Political Science Association

The American Political Science Association (APSA) is a professional association of political scientists in the United States. Founded in 1903 in the Tilton Memorial Library (now Tilton Hall) of Tulane University in New Orleans, it publishes four ...

, 1999.

* Timothy N. Thurber, Virginia Commonwealth University,Goldwaterism Triumphant?: Race and the Debate Among Republicans over the Direction of the GOP, 1964–1968

" Paper presented at the 2006 Conference of the Historical Society, Chapel Hill, NC. * Barbara Walters (2008), ''Audition: A Memoir''. Random House. . * Edward Brooke (1966), ''The Challenge of Change: Crisis in our Two-Party System''. Little, Brown, Boston.

Further reading

* * Kinkead, Gwen. ''Edward W. Brooke, Republican Senator from Massachusetts'' (Grossman Publishers, 1972).External links

Edward Brooke's oral history video excerpts

at The National Visionary Leadership Project * * , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Brooke, Edward William III 1919 births 2015 deaths African-American people in Massachusetts politics African-American United States senators African-American Episcopalians United States Army personnel of World War II Boston University School of Law alumni Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Congressional Gold Medal recipients Howard University alumni Massachusetts attorneys general Massachusetts Republicans Military personnel from Washington, D.C. Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Republican Party United States senators from Massachusetts United States Army officers Dunbar High School (Washington, D.C.) alumni 20th-century American Episcopalians African Americans in World War II African-American United States Army personnel Boston Finance Commission members African-American candidates for the United States Senate 20th-century African-American politicians 20th-century Massachusetts politicians 20th-century American lawyers 20th-century African-American lawyers 20th-century United States senators