Easter uprising on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed

The

The

In early April, Pearse issued orders to the Irish Volunteers for three days of "parades and manoeuvres" beginning on Easter Sunday. He had the authority to do this, as the Volunteers' Director of Organisation. The idea was that IRB members within the organisation would know these were orders to begin the rising, while men such as MacNeill and the British authorities would take it at face value.

On 9 April, the

In early April, Pearse issued orders to the Irish Volunteers for three days of "parades and manoeuvres" beginning on Easter Sunday. He had the authority to do this, as the Volunteers' Director of Organisation. The idea was that IRB members within the organisation would know these were orders to begin the rising, while men such as MacNeill and the British authorities would take it at face value.

On 9 April, the

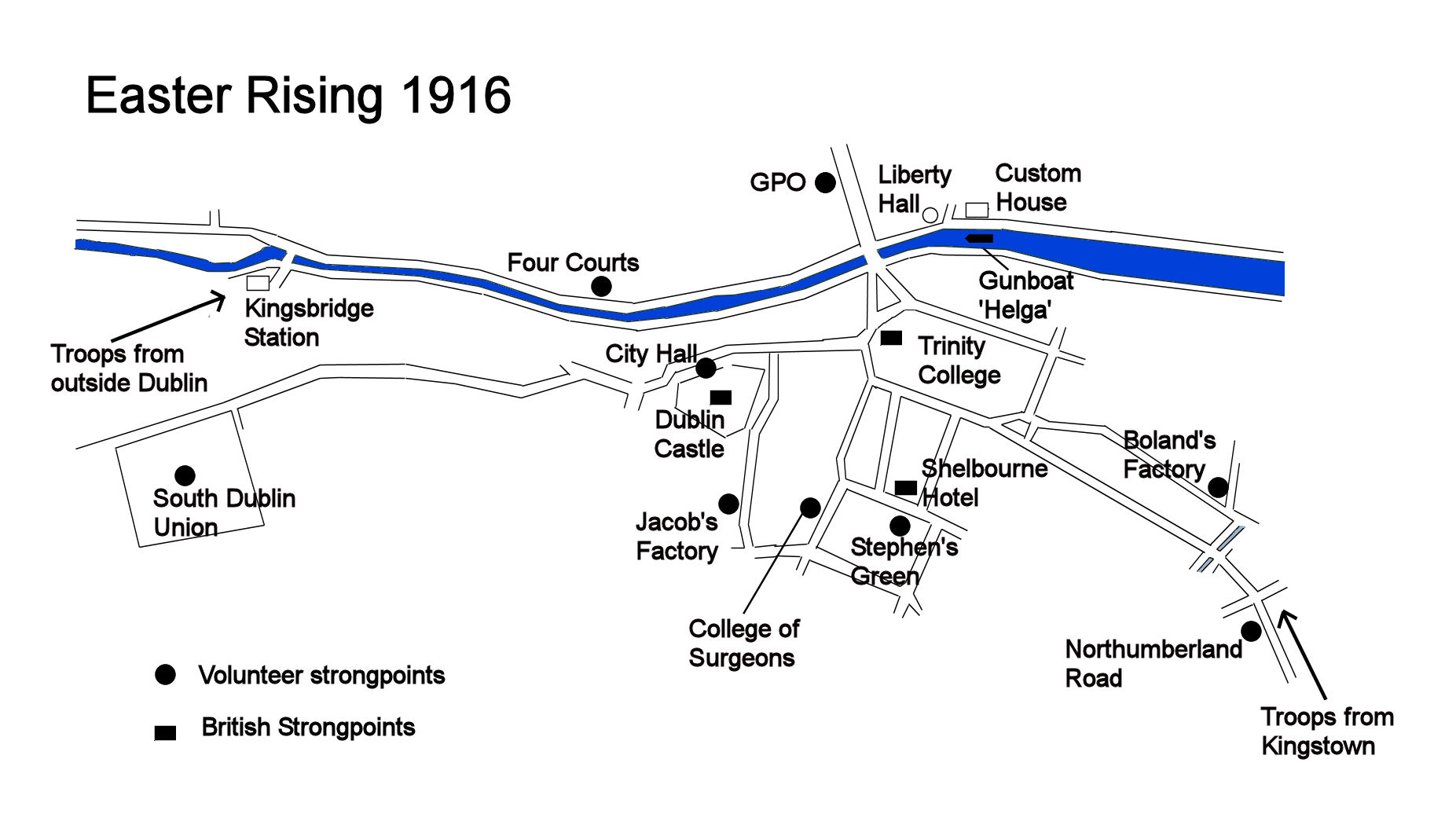

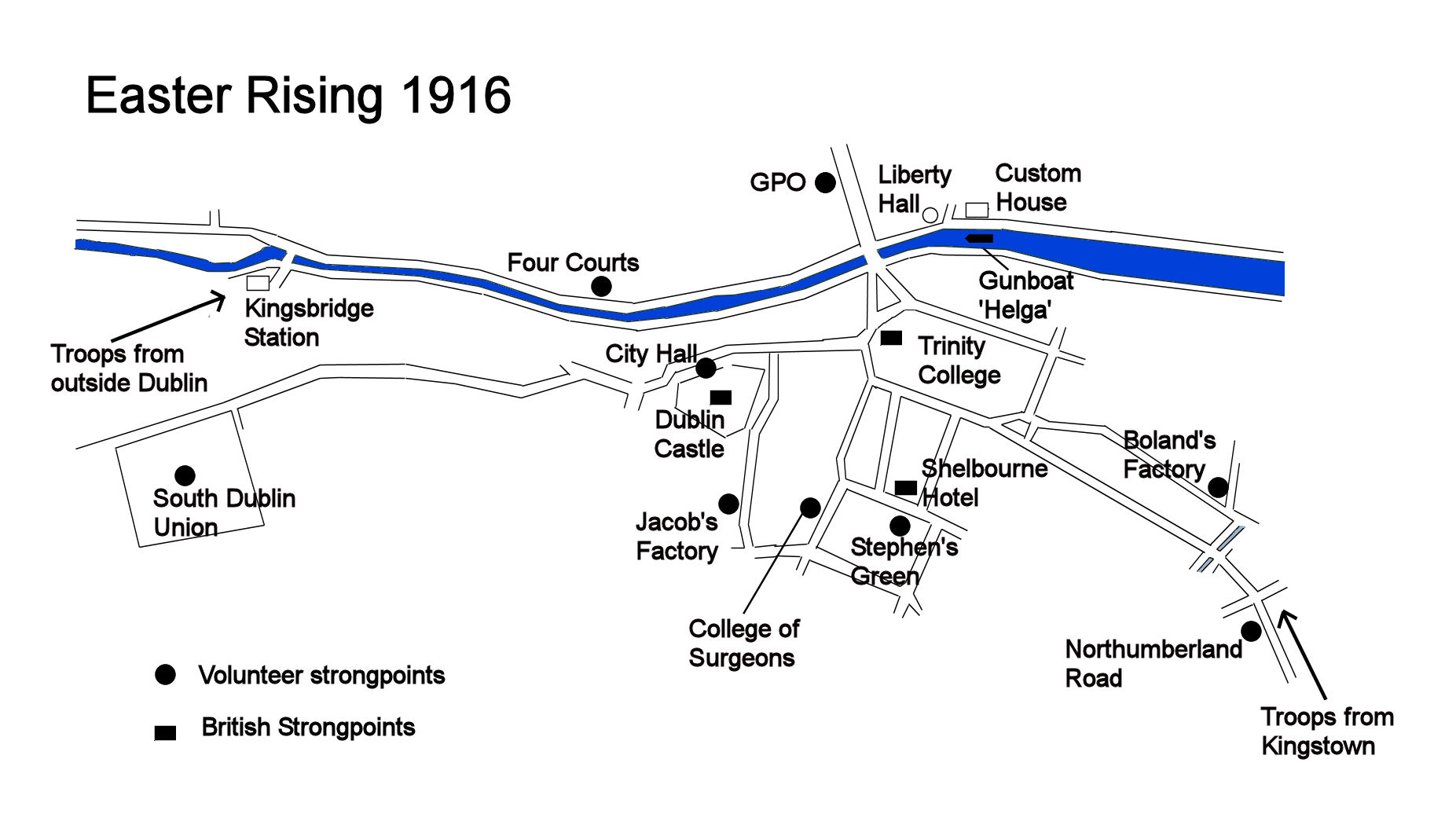

On the morning of Monday 24 April, about 1,200 members of the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army mustered at several locations in central Dublin. Among them were members of the all-female

On the morning of Monday 24 April, about 1,200 members of the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army mustered at several locations in central Dublin. Among them were members of the all-female  A contingent under Seán Connolly occupied Dublin City Hall and adjacent buildings. They attempted to seize neighbouring Dublin Castle, the heart of British rule in Ireland. As they approached the gate a lone and unarmed police sentry, James O'Brien, attempted to stop them and was shot dead by Connolly. According to some accounts, he was the first casualty of the Rising. The rebels overpowered the soldiers in the guardroom but failed to press further. The British Army's chief intelligence officer, Major Ivon Price, fired on the rebels while the Under-Secretary for Ireland, Sir Matthew Nathan, helped shut the castle gates. Unbeknownst to the rebels, the Castle was lightly guarded and could have been taken with ease. The rebels instead laid siege to the Castle from City Hall. Fierce fighting erupted there after British reinforcements arrived. The rebels on the roof exchanged fire with soldiers on the street. Seán Connolly was shot dead by a sniper, becoming the first rebel casualty. By the following morning, British forces had re-captured City Hall and taken the rebels prisoner.

The rebels did not attempt to take some other key locations, notably Trinity College Dublin, Trinity College, in the heart of the city centre and defended by only a handful of armed unionist students. Failure to capture the telephone exchange in Crown Alley left communications in the hands of the Government with GPO staff quickly repairing telephone wires that had been cut by the rebels. The failure to occupy strategic locations was attributed to lack of manpower. In at least two incidents, at Jacob's and Stephen's Green, the Volunteers and Citizen Army shot dead civilians trying to attack them or dismantle their barricades. Elsewhere, they hit civilians with their rifle butts to drive them off.

The British military were caught totally unprepared by the Rising and their response of the first day was generally un-coordinated. Two squadrons of British cavalry were sent to investigate what was happening. They took fire and casualties from rebel forces at the GPO and at the Four Courts.Coffey, Thomas M. ''Agony at Easter: The 1916 Irish Uprising'', pp. 38, 44, 155 As one troop passed Nelson's Pillar, the rebels opened fire from the GPO, killing three cavalrymen and two horses and fatally wounding a fourth man. The cavalrymen retreated and were withdrawn to barracks. On Mount Street, a group of Volunteer Training Corps (World War I), Volunteer Training Corps men stumbled upon the rebel position and four were killed before they reached Beggars Bush Barracks. Although ransacked, the barracks were never seized.

The only substantial combat of the first day of the Rising took place at the South Dublin Union where a picket (military), piquet from the Royal Irish Regiment (1684–1922), Royal Irish Regiment encountered an outpost of Éamonn Ceannt's force at the northwestern corner of the South Dublin Union. The British troops, after taking some casualties, managed to regroup and launch several assaults on the position before they forced their way inside and the small rebel force in the tin huts at the eastern end of the Union surrendered. However, the Union complex as a whole remained in rebel hands. A nurse in uniform, Margaret Keogh, was shot dead by British soldiers at the Union. She is believed to have been the first civilian killed in the Rising.

Three unarmed Dublin Metropolitan Police were shot dead on the first day of the Rising and their Commissioner pulled them off the streets. Partly as a result of the police withdrawal, a wave of looting broke out in the city centre, especially in the area of O'Connell Street (still officially called "Sackville Street" at the time).

A contingent under Seán Connolly occupied Dublin City Hall and adjacent buildings. They attempted to seize neighbouring Dublin Castle, the heart of British rule in Ireland. As they approached the gate a lone and unarmed police sentry, James O'Brien, attempted to stop them and was shot dead by Connolly. According to some accounts, he was the first casualty of the Rising. The rebels overpowered the soldiers in the guardroom but failed to press further. The British Army's chief intelligence officer, Major Ivon Price, fired on the rebels while the Under-Secretary for Ireland, Sir Matthew Nathan, helped shut the castle gates. Unbeknownst to the rebels, the Castle was lightly guarded and could have been taken with ease. The rebels instead laid siege to the Castle from City Hall. Fierce fighting erupted there after British reinforcements arrived. The rebels on the roof exchanged fire with soldiers on the street. Seán Connolly was shot dead by a sniper, becoming the first rebel casualty. By the following morning, British forces had re-captured City Hall and taken the rebels prisoner.

The rebels did not attempt to take some other key locations, notably Trinity College Dublin, Trinity College, in the heart of the city centre and defended by only a handful of armed unionist students. Failure to capture the telephone exchange in Crown Alley left communications in the hands of the Government with GPO staff quickly repairing telephone wires that had been cut by the rebels. The failure to occupy strategic locations was attributed to lack of manpower. In at least two incidents, at Jacob's and Stephen's Green, the Volunteers and Citizen Army shot dead civilians trying to attack them or dismantle their barricades. Elsewhere, they hit civilians with their rifle butts to drive them off.

The British military were caught totally unprepared by the Rising and their response of the first day was generally un-coordinated. Two squadrons of British cavalry were sent to investigate what was happening. They took fire and casualties from rebel forces at the GPO and at the Four Courts.Coffey, Thomas M. ''Agony at Easter: The 1916 Irish Uprising'', pp. 38, 44, 155 As one troop passed Nelson's Pillar, the rebels opened fire from the GPO, killing three cavalrymen and two horses and fatally wounding a fourth man. The cavalrymen retreated and were withdrawn to barracks. On Mount Street, a group of Volunteer Training Corps (World War I), Volunteer Training Corps men stumbled upon the rebel position and four were killed before they reached Beggars Bush Barracks. Although ransacked, the barracks were never seized.

The only substantial combat of the first day of the Rising took place at the South Dublin Union where a picket (military), piquet from the Royal Irish Regiment (1684–1922), Royal Irish Regiment encountered an outpost of Éamonn Ceannt's force at the northwestern corner of the South Dublin Union. The British troops, after taking some casualties, managed to regroup and launch several assaults on the position before they forced their way inside and the small rebel force in the tin huts at the eastern end of the Union surrendered. However, the Union complex as a whole remained in rebel hands. A nurse in uniform, Margaret Keogh, was shot dead by British soldiers at the Union. She is believed to have been the first civilian killed in the Rising.

Three unarmed Dublin Metropolitan Police were shot dead on the first day of the Rising and their Commissioner pulled them off the streets. Partly as a result of the police withdrawal, a wave of looting broke out in the city centre, especially in the area of O'Connell Street (still officially called "Sackville Street" at the time).

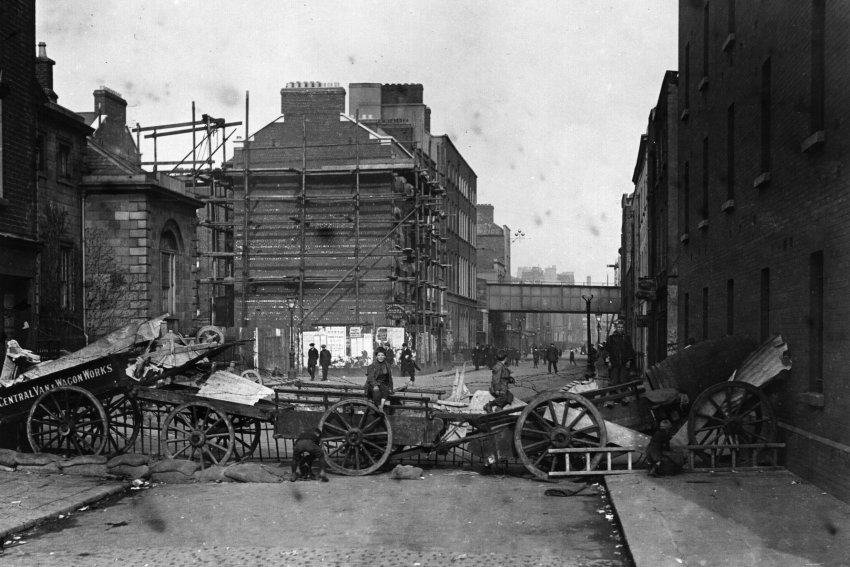

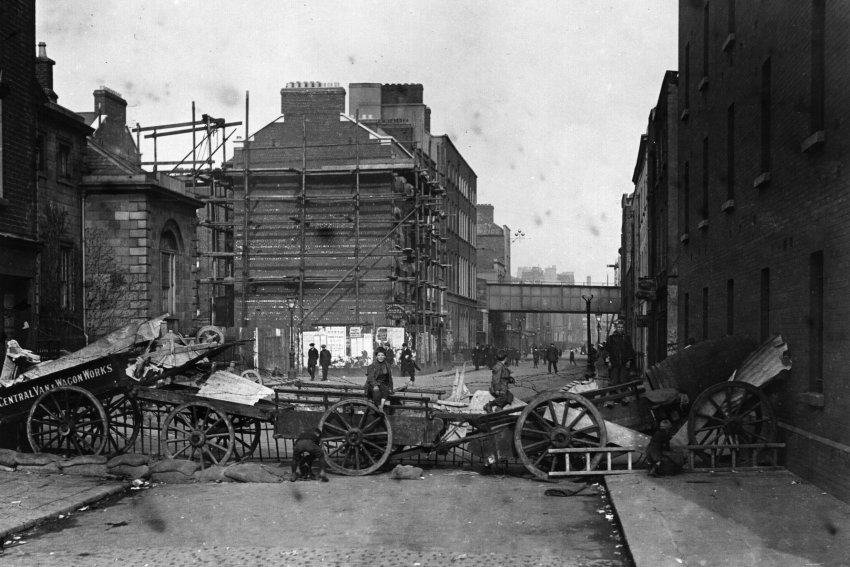

The third major scene of fighting during the week was in the area of North King Street, north of the Four Courts. The rebels had established strong outposts in the area, occupying numerous small buildings and barricading the streets. From Thursday to Saturday, the British made repeated attempts to capture the area, in what was some of the fiercest fighting of the Rising. As the troops moved in, the rebels continually opened fire from windows and behind chimneys and barricades. At one point, a platoon led by Major Sheppard made a Charge (warfare), bayonet charge on one of the barricades but was cut down by rebel fire. The British employed machine guns and attempted to avoid direct fire by using improvised fighting vehicle, makeshift armoured trucks, and by mouse-holing through the inside walls of terraced houses to get near the rebel positions. By the time of the rebel headquarters' surrender on Saturday, the South Staffordshire Regiment under Colonel Taylor had advanced only down the street at a cost of 11 dead and 28 wounded. The enraged troops broke into the houses along the street and shot or bayoneted fifteen unarmed male civilians whom they accused of being rebel fighters.

Elsewhere, at Cathal Brugha Barracks, Portobello Barracks, an officer named Bowen Colthurst summary execution, summarily executed six civilians, including the pacifist nationalist activist, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington. These instances of British troops killing Irish civilians would later be highly controversial in Ireland.

The third major scene of fighting during the week was in the area of North King Street, north of the Four Courts. The rebels had established strong outposts in the area, occupying numerous small buildings and barricading the streets. From Thursday to Saturday, the British made repeated attempts to capture the area, in what was some of the fiercest fighting of the Rising. As the troops moved in, the rebels continually opened fire from windows and behind chimneys and barricades. At one point, a platoon led by Major Sheppard made a Charge (warfare), bayonet charge on one of the barricades but was cut down by rebel fire. The British employed machine guns and attempted to avoid direct fire by using improvised fighting vehicle, makeshift armoured trucks, and by mouse-holing through the inside walls of terraced houses to get near the rebel positions. By the time of the rebel headquarters' surrender on Saturday, the South Staffordshire Regiment under Colonel Taylor had advanced only down the street at a cost of 11 dead and 28 wounded. The enraged troops broke into the houses along the street and shot or bayoneted fifteen unarmed male civilians whom they accused of being rebel fighters.

Elsewhere, at Cathal Brugha Barracks, Portobello Barracks, an officer named Bowen Colthurst summary execution, summarily executed six civilians, including the pacifist nationalist activist, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington. These instances of British troops killing Irish civilians would later be highly controversial in Ireland.

The headquarters garrison at the GPO was forced to evacuate after days of shelling when a fire caused by the shells spread to the GPO. Connolly had been incapacitated by a bullet wound to the ankle and had passed command on to Pearse. The O'Rahilly was killed in a sortie from the GPO. They tunnelled through the walls of the neighbouring buildings in order to evacuate the Post Office without coming under fire and took up a new position in 16 Moore Street. The young Seán McLoughlin (communist), Seán McLoughlin was given military command and planned a breakout, but Pearse realised this plan would lead to further loss of civilian life.

On the eve of the surrender, there had been about 35 Cumann na mBan women remaining in the GPO. In the final group that left with Pearse and Connolly, there were three: Connolly's aide de camp, Winifred Carney, who had entered with the original ICA contingent, and the dispatchers and nurses Elizabeth O'Farrell, and Julia Grenan.

On Saturday 29 April, from this new headquarters, Pearse issued an order for all companies to surrender. Pearse Unconditional surrender, surrendered unconditionally to Brigadier-General Lowe. The surrender document read:

The other posts surrendered only after Pearse's surrender order, carried by O'Farrell, reached them. Sporadic fighting, therefore, continued until Sunday, when word of the surrender was got to the other rebel garrisons. Command of British forces had passed from Lowe to General John Maxwell, who arrived in Dublin just in time to take the surrender. Maxwell was made temporary military governor of Ireland.

The headquarters garrison at the GPO was forced to evacuate after days of shelling when a fire caused by the shells spread to the GPO. Connolly had been incapacitated by a bullet wound to the ankle and had passed command on to Pearse. The O'Rahilly was killed in a sortie from the GPO. They tunnelled through the walls of the neighbouring buildings in order to evacuate the Post Office without coming under fire and took up a new position in 16 Moore Street. The young Seán McLoughlin (communist), Seán McLoughlin was given military command and planned a breakout, but Pearse realised this plan would lead to further loss of civilian life.

On the eve of the surrender, there had been about 35 Cumann na mBan women remaining in the GPO. In the final group that left with Pearse and Connolly, there were three: Connolly's aide de camp, Winifred Carney, who had entered with the original ICA contingent, and the dispatchers and nurses Elizabeth O'Farrell, and Julia Grenan.

On Saturday 29 April, from this new headquarters, Pearse issued an order for all companies to surrender. Pearse Unconditional surrender, surrendered unconditionally to Brigadier-General Lowe. The surrender document read:

The other posts surrendered only after Pearse's surrender order, carried by O'Farrell, reached them. Sporadic fighting, therefore, continued until Sunday, when word of the surrender was got to the other rebel garrisons. Command of British forces had passed from Lowe to General John Maxwell, who arrived in Dublin just in time to take the surrender. Maxwell was made temporary military governor of Ireland.

The Rising was planned to occur across the nation, but MacNeill's countermanding order coupled with the failure to secure German arms hindered this objective significantly. Charles Townshend (historian), Charles Townshend contended that serious intentions for a national Rising were meagre, being diminished by a focus upon Dublin – although this is an increasingly contentious notion.

In the south, around 1,200 Volunteers commanded by Tomás Mac Curtain mustered on the Sunday in Cork (city), Cork, but they dispersed on Wednesday after receiving nine contradictory orders by dispatch from the Volunteer leadership in Dublin. At their Sheares Street headquarters, some of the Volunteers engaged in a standoff with British forces. Much to the anger of many Volunteers, MacCurtain, under pressure from Catholic clergy, agreed to surrender his men's arms to the British. The only violence in County Cork occurred when the RIC attempted to raid the home of the Kent family of Bawnard, Kent family. The Kent brothers, who were Volunteers, engaged in a three-hour firefight with the RIC. An RIC officer and one of the brothers were killed, while another brother was later executed. Virtually all rebel family homes were raided, either during or after the Rising.

In the north, Volunteer companies were mobilised in County Tyrone at Coalisland (including 132 men from Belfast led by IRB President Dennis McCullough) and Carrickmore, under the leadership of Patrick McCartan. They also mobilised at Creeslough, County Donegal under Daniel Kelly and James McNulty (Irish activist), James McNulty. However, in part because of the confusion caused by the countermanding order, the Volunteers in these locations dispersed without fighting. McCartan claimed that the decision by the leadership of the rebellion not to share plans led to poor communication and uncertainty. McCartan wrote that Tyrone Volunteers could have

The Rising was planned to occur across the nation, but MacNeill's countermanding order coupled with the failure to secure German arms hindered this objective significantly. Charles Townshend (historian), Charles Townshend contended that serious intentions for a national Rising were meagre, being diminished by a focus upon Dublin – although this is an increasingly contentious notion.

In the south, around 1,200 Volunteers commanded by Tomás Mac Curtain mustered on the Sunday in Cork (city), Cork, but they dispersed on Wednesday after receiving nine contradictory orders by dispatch from the Volunteer leadership in Dublin. At their Sheares Street headquarters, some of the Volunteers engaged in a standoff with British forces. Much to the anger of many Volunteers, MacCurtain, under pressure from Catholic clergy, agreed to surrender his men's arms to the British. The only violence in County Cork occurred when the RIC attempted to raid the home of the Kent family of Bawnard, Kent family. The Kent brothers, who were Volunteers, engaged in a three-hour firefight with the RIC. An RIC officer and one of the brothers were killed, while another brother was later executed. Virtually all rebel family homes were raided, either during or after the Rising.

In the north, Volunteer companies were mobilised in County Tyrone at Coalisland (including 132 men from Belfast led by IRB President Dennis McCullough) and Carrickmore, under the leadership of Patrick McCartan. They also mobilised at Creeslough, County Donegal under Daniel Kelly and James McNulty (Irish activist), James McNulty. However, in part because of the confusion caused by the countermanding order, the Volunteers in these locations dispersed without fighting. McCartan claimed that the decision by the leadership of the rebellion not to share plans led to poor communication and uncertainty. McCartan wrote that Tyrone Volunteers could have

The Fingal Battalion: A Blueprint for the Future?

. ''The Irish Sword''. Military History Society of Ireland, 2011. pp. 9–13 The Volunteers moved against the RIC barracks in Swords, Donabate and Garristown, forcing the RIC to surrender and seizing all the weapons. They also damaged railway lines and cut telegraph wires. The railway line at Blanchardstown was bombed to prevent a troop train from reaching Dublin. This derailed a cattle train, which had been sent ahead of the troop train. The only large-scale engagement of the Rising, outside Dublin city, was at Ashbourne, County Meath. On Friday, about 35 Fingal Volunteers surrounded the Ashbourne RIC barracks and called on it to surrender, but the RIC responded with a volley of gunfire. A firefight followed, and the RIC surrendered after the Volunteers attacked the building with a homemade grenade. Before the surrender could be taken, up to sixty RIC men arrived in a convoy, sparking a five-hour gun battle, in which eight RIC men were killed and 18 wounded. Two Volunteers were also killed and five wounded, and a civilian was fatally shot. The RIC surrendered and were disarmed. Ashe let them go after warning them not to fight against the Irish Republic again. Ashe's men camped at Kilsalaghan near Dublin until they received orders to surrender on Saturday. The Fingal Battalion's tactics during the Rising foreshadowed those of the IRA during the Irish War of Independence, War of Independence that followed. Volunteer contingents also mobilised nearby in counties Meath and Louth but proved unable to link up with the North Dublin unit until after it had surrendered. In County Louth, Volunteers shot dead an RIC man near the village of Castlebellingham on 24 April, in an incident in which 15 RIC men were also taken prisoner.

The Irish Rebellion of 1916: a brief history of the revolt and its suppression

'' (Chapter IV: Outbreaks in the Country). BiblioBazaar, 2009. pp. 127–152 Volunteer officer Paul Galligan had cycled 200 km from rebel headquarters in Dublin with orders to mobilise.Dorney, John

The Easter Rising in County Wexford

. The Irish Story. 10 April 2012. They blocked all roads into the town and made a brief attack on the RIC barracks, but chose to blockade it rather than attempt to capture it. They flew the tricolour over the Athenaeum building, which they had made their headquarters, and paraded uniformed in the streets. They also occupied Vinegar Hill, where the Society of United Irishmen, United Irishmen had Battle of Vinegar Hill, made a last stand in the Irish Rebellion of 1798, 1798 rebellion. The public largely supported the rebels and many local men offered to join them. By Saturday, up to 1,000 rebels had been mobilised, and a detachment was sent to occupy the nearby village of Ferns, County Wexford, Ferns. In Wexford, the British assembled a column of 1,000 soldiers (including the Connaught Rangers), two field guns and a QF 4.7-inch Gun Mk I–IV, 4.7 inch naval gun on a makeshift armoured train. On Sunday, the British sent messengers to Enniscorthy, informing the rebels of Pearse's surrender order. However, the Volunteer officers were sceptical. Two of them were escorted by the British to Arbour Hill Prison, where Pearse confirmed the surrender order.

The Easter Rising in Galway, 1916

. The Irish Story. 4 March 2016. However, his men were poorly armed, with only 25 rifles, 60 revolvers, 300 shotguns and some homemade grenades – many of them only had pike (weapon), pikes.Mark McCarthy & Shirley Wrynn

''County Galway's 1916 Rising: A Short History''

. Galway County Council. Most of the action took place in a rural area to the east of Galway city. They made unsuccessful attacks on the RIC barracks at Clarinbridge and Oranmore, captured several officers, and bombed a bridge and railway line, before taking up position near Athenry. There was also a skirmish between rebels and an RIC mobile patrol at Carnmore crossroads. A constable, Patrick Whelan, was shot dead after he had called to the rebels: "Surrender, boys, I know ye all". On Wednesday, arrived in Galway Bay and shelled the countryside on the northeastern edge of Galway. The rebels retreated southeast to Moyode, an abandoned country house and estate. From here they set up lookout posts and sent out scouting parties. On Friday, landed 200 Royal Marines and began shelling the countryside near the rebel position. The rebels retreated further south to Limepark, another abandoned country house. Deeming the situation to be hopeless, they dispersed on Saturday morning. Many went home and were arrested following the Rising, while others, including Mellows, went "on the run". By the time British reinforcements arrived in the west, the Rising there had already disintegrated.

The Easter Rising resulted in at least 485 deaths, according to the Glasnevin Trust.

Of those killed:

* 260 (about 54%) were civilians

* 126 (about 26%) were U.K. forces (120 U.K. military personnel, 5 Volunteer Training Corps (World War I), Volunteer Training Corps members, and one Canadian soldier)

** 35 – Irish Regiments:-

*** 11 – Royal Dublin Fusiliers

*** 10 – Royal Irish Rifles

*** 9 – Royal Irish Regiment

*** 2 – Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers

*** 2 – Royal Irish Fusiliers

*** 1 – Leinster Regiment

** 74 – British Regiments:-

*** 29 – Sherwood Foresters

*** 15 – South Staffordshire

*** 2 – North Staffordshire

*** 1 – Royal Field Artillery

*** 4 – Royal Engineers

*** 5 – Army Service Corps

*** 10 – Lancers

*** 7 – 8th Hussars

*** 2 – 2nd King Edwards Horse

*** 3 – Yeomanry

** 1 – Royal Navy

* 82 (about 16%) were Irish rebel forces (64 Irish Volunteers, 15 Irish Citizen Army and 3

The Easter Rising resulted in at least 485 deaths, according to the Glasnevin Trust.

Of those killed:

* 260 (about 54%) were civilians

* 126 (about 26%) were U.K. forces (120 U.K. military personnel, 5 Volunteer Training Corps (World War I), Volunteer Training Corps members, and one Canadian soldier)

** 35 – Irish Regiments:-

*** 11 – Royal Dublin Fusiliers

*** 10 – Royal Irish Rifles

*** 9 – Royal Irish Regiment

*** 2 – Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers

*** 2 – Royal Irish Fusiliers

*** 1 – Leinster Regiment

** 74 – British Regiments:-

*** 29 – Sherwood Foresters

*** 15 – South Staffordshire

*** 2 – North Staffordshire

*** 1 – Royal Field Artillery

*** 4 – Royal Engineers

*** 5 – Army Service Corps

*** 10 – Lancers

*** 7 – 8th Hussars

*** 2 – 2nd King Edwards Horse

*** 3 – Yeomanry

** 1 – Royal Navy

* 82 (about 16%) were Irish rebel forces (64 Irish Volunteers, 15 Irish Citizen Army and 3

On Tuesday 25 April, Dubliner Francis Sheehy Skeffington, a pacifist nationalist activist, was arrested and then taken as hostage and human shield by Captain John Bowen-Colthurst; that night Bowen-Colthurst shot dead a teenage boy. Skeffington was executed the next day – alongside two journalists. Two hours later, Bowen-Colthurst captured the Labour Party (Ireland), Labour Party councillor and IRB lieutenant, Richard O'Carroll and had him shot in the street. Major Sir Francis Vane raised concerns over Bowen-Colthurst's actions and saw to him being court martialled. Bowen-Colthurst was found guilty but insane and was sentenced to an insane asylum. Owing to political pressure, an inquiry soon transpired, revealing the murders and their cover-up. The killing of Skeffington and others provoked outrage among citizens.

The other incident was the "North King Street Massacre". On the night of 28–29 April, British soldiers of the South Staffordshire Regiment, under Colonel Henry Taylor, had burst into houses on North King Street and killed fifteen male civilians whom they accused of being rebels. The soldiers shot or bayoneted the victims, and then secretly buried some of them in cellars or backyards after robbing them. The area saw some of the fiercest fighting of the Rising and the British had taken heavy casualties for little gain. Maxwell attempted to excuse the killings and argued that the rebels were ultimately responsible. He claimed that "the rebels wore no uniform" and that the people of North King Street were rebel sympathisers. Maxwell concluded that such incidents "are absolutely unavoidable in such a business as this" and that "under the circumstance the troops [...] behaved with the greatest restraint". A private brief, prepared for the Prime Minister, said the soldiers "had orders not to take any prisoners" but took it to mean they were to shoot any suspected rebel. The City Coroner's inquest found that soldiers had killed "unarmed and unoffending" residents. The military court of inquiry ruled that no specific soldiers could be held responsible, and no action was taken.

On Tuesday 25 April, Dubliner Francis Sheehy Skeffington, a pacifist nationalist activist, was arrested and then taken as hostage and human shield by Captain John Bowen-Colthurst; that night Bowen-Colthurst shot dead a teenage boy. Skeffington was executed the next day – alongside two journalists. Two hours later, Bowen-Colthurst captured the Labour Party (Ireland), Labour Party councillor and IRB lieutenant, Richard O'Carroll and had him shot in the street. Major Sir Francis Vane raised concerns over Bowen-Colthurst's actions and saw to him being court martialled. Bowen-Colthurst was found guilty but insane and was sentenced to an insane asylum. Owing to political pressure, an inquiry soon transpired, revealing the murders and their cover-up. The killing of Skeffington and others provoked outrage among citizens.

The other incident was the "North King Street Massacre". On the night of 28–29 April, British soldiers of the South Staffordshire Regiment, under Colonel Henry Taylor, had burst into houses on North King Street and killed fifteen male civilians whom they accused of being rebels. The soldiers shot or bayoneted the victims, and then secretly buried some of them in cellars or backyards after robbing them. The area saw some of the fiercest fighting of the Rising and the British had taken heavy casualties for little gain. Maxwell attempted to excuse the killings and argued that the rebels were ultimately responsible. He claimed that "the rebels wore no uniform" and that the people of North King Street were rebel sympathisers. Maxwell concluded that such incidents "are absolutely unavoidable in such a business as this" and that "under the circumstance the troops [...] behaved with the greatest restraint". A private brief, prepared for the Prime Minister, said the soldiers "had orders not to take any prisoners" but took it to mean they were to shoot any suspected rebel. The City Coroner's inquest found that soldiers had killed "unarmed and unoffending" residents. The military court of inquiry ruled that no specific soldiers could be held responsible, and no action was taken.

Support for the rebels did exist among Dubliners, expressed through both crowds cheering at prisoners and reverent silence. With martial law seeing this expression prosecuted, many would-be supporters elected to remain silent although "a strong undercurrent of disloyalty" was still felt. Drawing upon this support, and amidst the deluge of nationalist ephemera, the significantly popular ''Catholic Bulletin'' eulogised Volunteers killed in action and implored readers to donate; entertainment was offered as an extension of those intentions, targeting local sectors to great success. The ''Bulletin''s Catholic character allowed it to evade the widespread censorship of press and seizure of republican propaganda; it therefore exposed many unaware readers to such propaganda.

Support for the rebels did exist among Dubliners, expressed through both crowds cheering at prisoners and reverent silence. With martial law seeing this expression prosecuted, many would-be supporters elected to remain silent although "a strong undercurrent of disloyalty" was still felt. Drawing upon this support, and amidst the deluge of nationalist ephemera, the significantly popular ''Catholic Bulletin'' eulogised Volunteers killed in action and implored readers to donate; entertainment was offered as an extension of those intentions, targeting local sectors to great success. The ''Bulletin''s Catholic character allowed it to evade the widespread censorship of press and seizure of republican propaganda; it therefore exposed many unaware readers to such propaganda.

File:GPO Easter Rising Plaque.jpg, Plaque commemorating the Easter Rising at the General Post Office (Dublin), General Post Office, Dublin, with the Irish text in Gaelic type, Gaelic script, and the English text in regular Latin script

File:Cobh Volunteers 1916 memorial.jpg, Memorial in Cobh, County Cork, to the Volunteers from that town

File:Offaly 1916 memorial.jpg, Memorial in Clonmacnoise commemorating men of County Offaly (then King's County) who fought in 1916: James Kenny, Kieran Kenny and Paddy McDonnell are named

File:Clonegal flag.jpg, Flag and copy of the Proclamation in Clonegal

"Review of Gerry Hunt's 'Blood Upon the Rose', part one"

, Pue's Occurrences, 2 November 2009 * ''1916 Seachtar na Cásca'' is a 2010 Irish TV documentary series based on the Easter Rising, telling about seven signatories of the rebellion. * ''The Dream of the Celt'' is a 2012 novel by the Nobel Prize winner in Literature Mario Vargas Llosa, based on the life and death of Roger Casement including his involvement with the Rising. * ''Rebellion (miniseries), Rebellion'' is a 2016 mini-series about the Easter Rising. * ''1916'' is a 2016 three-part documentary miniseries about the Easter Rising narrated by Liam Neeson. * ''Penance (2018 film), Penance'' is a 2018 Irish film set primarily in Donegal in 1916 and in Derry in 1969, in which the Rising is also featured.

excerpt

* Foy, Michael and Barton, Brian, ''The Easter Rising'' * * * C. Desmond Greaves, Greaves, C. Desmond, ''The Life and Times of James Connolly'' * * * * * * Conor Kostick, Kostick, Conor & Collins, Lorcan, ''The Easter Rising, A Guide to Dublin in 1916'' * F.S.L. Lyons, Lyons, F.S.L., ''Ireland Since the Famine'' * Dorothy Macardle, Macardle, Dorothy, ''The Irish Republic'' (Dublin 1951) * * * * * * * * * "Patrick Pearse and Patriotic Soteriology," in Yonah Alexander and Alan O'Day, eds, ''The Irish Terrorism Experience'', (Aldershot: Dartmouth) 1991 * Ó Broin, Leon, ''Dublin Castle & the 1916 Rising'', Sidgwick & Jackson, 1970 * * * * * * *

excerpt

* McKeown, Eitne, 'A Family in the Rising' ''Dublin Electricity Supply Board Journal'' 1966. * Murphy, John A., ''Ireland in the Twentieth Century'' * * Purdon, Edward, ''The 1916 Rising'' * Shaw, Francis, S.J., "The Canon of Irish History: A Challenge", in ''Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review'', LXI, 242, 1972, pp. 113–52

Easter 1916 – Digital Heritage Website

The 1916 Rising – an Online Exhibition.

National Library of Ireland

The Letters of 1916 – Crowdsourcing ProjectTrinity College Dublin

* *

Lillian Stokes (1878–1955): account of the 1916 Easter Rising

Primary and secondary sources relating to the Easter Rising

(Sources database, National Library of Ireland)

Easter Rising site and walking tour of 1916 Dublin

News articles and letters to the editor in ''The Age'', 27 April 1916

The 1916 Rising by Norman Teeling

a 10-painting suite acquired by An Post for permanent display at the General Post Office (Dublin)

The Easter Rising

– ''BBC History''

The Irish Story archive on the Rising

Easter Rising website

Lenin's discussion of the importance of the rebellion appears in Section 10: The Irish Rebellion of 1916

Bureau of Military History – Witness Statements Online (PDF files)

{{Authority control Easter Rising, 1916 in Ireland 20th-century rebellions Anti-imperialism in Europe April 1916 in Europe Conflicts in 1916 Attacks in Ireland History of County Dublin History of Ireland (1801–1923) Ireland–United Kingdom relations Rebellions in Ireland Rebellions against the British Empire Wars involving the United Kingdom Events that led to courts-martial May 1916 in Europe Uprisings during World War I

insurrection

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

in Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans

Irish republicanism () is the political movement for an Irish republic, void of any British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously elective and militant and has been both w ...

against British rule in Ireland

British colonial rule in Ireland built upon the 12th-century Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland on behalf of the English king and eventually spanned several centuries that involved British control of parts, or the entirety, of the island of Irel ...

with the aim of establishing an independent Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( or ) was a Revolutionary republic, revolutionary state that Irish Declaration of Independence, declared its independence from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdict ...

while the United Kingdom was fighting the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. It was the most significant uprising in Ireland since the rebellion of 1798 and the first armed conflict of the Irish revolutionary period

The revolutionary period in Irish history was the period in the 1910s and early 1920s when Irish nationalist opinion shifted from the Home Rule-supporting Irish Parliamentary Party to the republican Sinn Féin movement. There were several ...

. Sixteen of the Rising's leaders were executed starting in May 1916. The nature of the executions, and subsequent political developments, ultimately contributed to an increase in popular support for Irish independence.

Organised by a seven-man Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

, the Rising began on Easter Monday

Easter Monday is the second day of Eastertide and a public holiday in more than 50 predominantly Christian countries. In Western Christianity it marks the second day of the Octave of Easter; in Eastern Christianity it marks the second day of Br ...

, 24 April 1916 and lasted for six days. Members of the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers (), also known as the Irish Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteer Army, was a paramilitary organisation established in 1913 by nationalists and republicans in Ireland. It was ostensibly formed in response to the format ...

, led by schoolmaster and Irish language activist Patrick Pearse

Patrick Henry Pearse (also known as Pádraig or Pádraic Pearse; ; 10 November 1879 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish teacher, barrister, Irish poetry, poet, writer, Irish nationalism, nationalist, Irish republicanism, republican political activist a ...

, joined by the smaller Irish Citizen Army

The Irish Citizen Army (), or ICA, was a paramilitary group first formed in Dublin to defend the picket lines and street demonstrations of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) against the police during the Great Dublin Lock ...

of James Connolly

James Connolly (; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was a Scottish people, Scottish-born Irish republicanism, Irish republican, socialist, and trade union leader, executed for his part in the Easter Rising, 1916 Easter Rising against British rule i ...

and 200 women of Cumann na mBan

Cumann na mBan (; but in English termed The Irishwomen's Council), abbreviated C na mB, is an Irish republican women's paramilitary organisation formed in Dublin on 2 April 1914, merging with and dissolving Inghinidhe na hÉireann, and in 191 ...

seized strategically important buildings in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

and proclaimed the Irish Republic. The British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

brought in thousands of reinforcements as well as artillery and a gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

. There was street fighting on the routes into the city centre, where the rebels slowed the British advance and inflicted many casualties. Elsewhere in Dublin, the fighting mainly consisted of sniping and long-range gun battles. The main rebel positions were gradually surrounded and bombarded with artillery. There were isolated actions in other parts of Ireland; Volunteer leader Eoin MacNeill

Eoin MacNeill (; born John McNeill; 15 May 1867 – 15 October 1945) was an Irish scholar, Irish language enthusiast, Gaelic revivalist, nationalist, and politician who served as Minister for Education from 1922 to 1925, Ceann Comhairle of D ...

had issued a countermand in a bid to halt the Rising, which greatly reduced the extent of the rebel actions.

With much greater numbers and heavier weapons, the British Army suppressed the Rising. Pearse agreed to an unconditional surrender on Saturday 29 April, although sporadic fighting continued briefly. After the surrender, the country remained under martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

. About 3,500 people were taken prisoner by the British and 1,800 of them were sent to internment camps or prisons in Britain. Most of the leaders of the Rising were executed following courts martial. The Rising brought physical force republicanism

Irish republicanism () is the political movement for an Irish republic, void of any British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously elective and militant and has been both w ...

back to the forefront of Irish politics, which for nearly fifty years had been dominated by constitutional nationalism. Opposition to the British reaction to the Rising contributed to changes in public opinion and the move toward independence, as shown in the December 1918 election in Ireland which was won by the Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

party, which convened the First Dáil

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

and declared independence.

Of the 485 people killed, 260 were civilians, 143 were British military and police personnel, and 82 were Irish rebels, including 16 rebels executed for their roles in the Rising. More than 2,600 people were wounded. Many of the civilians were killed or wounded by British artillery fire or were mistaken for rebels. Others were caught in the crossfire during firefights between the British and the rebels. The shelling and resulting fires left parts of central Dublin in ruins.

Background

The

The Acts of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland (previously in personal union) to create the United Kingdom of G ...

united the Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

and the Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland (; , ) was a dependent territory of Kingdom of England, England and then of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain from 1542 to the end of 1800. It was ruled by the monarchs of England and then List of British monarchs ...

as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into one sovereign state, established by the Acts of Union 1800, Acts of Union in 1801. It continued in this form until ...

, abolishing the Irish Parliament and giving Ireland representation in the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

. From early on, many Irish nationalists

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

opposed the union and the continued lack of adequate political representation, along with the British government's handling of Ireland and Irish people, particularly the Great Famine. The union was closely preceded by and formed partly in response to an Irish uprising – whose centenary would prove an influence on the Easter Rising. Three more rebellions ensued: one in 1803

Events January–March

* January 1 – The first edition of Alexandre Balthazar Laurent Grimod de La Reynière's ''Almanach des gourmands'', the first guide to restaurant cooking, is published in Paris.

* January 4 – William Symingt ...

, another in 1848

1848 is historically famous for the wave of revolutions, a series of widespread struggles for more liberal governments, which broke out from Brazil to Hungary; although most failed in their immediate aims, they significantly altered the polit ...

and one in 1867

There were only 354 days this year in the newly purchased territory of Alaska. When the territory transferred from the Russian Empire to the United States, the calendric transition from the Julian to the Gregorian Calendar was made with only 1 ...

. All were failures.

Opposition took other forms: constitutional (the Repeal Association

The Repeal Association was an Irish mass membership political movement set up by Daniel O'Connell in 1830 to campaign for a repeal of the Acts of Union of 1800 between Great Britain and Ireland.

The Association's aim was to revert Ireland to ...

; the Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parliam ...

) and social (disestablishment of the Church of Ireland

The Irish Church Act 1869 ( 32 & 33 Vict. c. 42) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which separated the Church of Ireland from the Church of England and disestablished the former, a body that commanded the adherence of a small mi ...

; the Land League

The Irish National Land League ( Irish: ''Conradh na Talún''), also known as the Land League, was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which organised tenant farmers in their resistance to exactions of landowners. Its prima ...

). The Irish Home Rule movement

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to ...

sought to achieve self-government for Ireland, within the United Kingdom. In 1886, the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nati ...

under Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom from 1875 to 1891, Leader of the Home Rule Leag ...

succeeded in having the First Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Bill 1886, commonly known as the First Home Rule Bill, was the first major attempt made by a British government to enact a law creating home rule for part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was intr ...

introduced in the British parliament, but it was defeated. The Second Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Bill 1893 (known generally as the Second Home Rule Bill) was the second attempt made by Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone, as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, to enact a system of home rule for Ireland. ...

of 1893 was passed by the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

but rejected by the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

.

After the death of Parnell, younger and more radical nationalists became disillusioned with parliamentary politics and turned toward more extreme forms of separatism. The Gaelic Athletic Association

The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA; ; CLG) is an Irish international amateur sports, amateur sporting and cultural organisation, focused primarily on promoting indigenous Gaelic games and pastimes, which include the traditional Irish sports o ...

, the Gaelic League

(; historically known in English as the Gaelic League) is a social and cultural organisation which promotes the Irish language in Ireland and worldwide. The organisation was founded in 1893 with Douglas Hyde as its first president, when it eme ...

, and the cultural revival under W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (, 13 June 186528 January 1939), popularly known as W. B. Yeats, was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer, and literary critic who was one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the ...

and Augusta, Lady Gregory

Isabella Augusta, Lady Gregory (; 15 March 1852 – 22 May 1932) was an Anglo-Irish people, Anglo-Irish dramatist, Folklore, folklorist and theatre manager. With William Butler Yeats and Edward Martyn, she co-founded the Irish Literary Theatre a ...

, together with the new political thinking of Arthur Griffith

Arthur Joseph Griffith (; 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922) was an Irish writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn Féin. He led the Irish delegation at the negotiations that produced the 1921 Anglo-Irish Trea ...

expressed in his newspaper ''Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

'' and organisations such as the National Council and the Sinn Féin League, led many Irish people to identify with the idea of an independent Gaelic

Gaelic (pronounced for Irish Gaelic and for Scots Gaelic) is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". It may refer to:

Languages

* Gaelic languages or Goidelic languages, a linguistic group that is one of the two branches of the Insul ...

Ireland.

The Third Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 ( 4 & 5 Geo. 5. c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-gover ...

was introduced by British Liberal Prime Minister H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

in 1912. Irish Unionists, who were overwhelmingly Protestants, opposed it, as they did not want to be ruled by a Catholic-dominated Irish government. Led by Sir Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, Baron Carson, PC, PC (Ire), KC (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician, barrister and judge, who was the Attorney General and Solicitor Gen ...

and James Craig, they formed the Ulster Volunteers

The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the ...

(UVF) in January 1913. The UVF's opposition included arming themselves, in the event that they had to resist by force.

Seeking to defend Home Rule, the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers (), also known as the Irish Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteer Army, was a paramilitary organisation established in 1913 by nationalists and republicans in Ireland. It was ostensibly formed in response to the format ...

was formed in November 1913. Although sporting broadly open membership and without avowed support for separatism, the executive branch of the Irish Volunteers – excluding leadership

Leadership, is defined as the ability of an individual, group, or organization to "", influence, or guide other individuals, teams, or organizations.

"Leadership" is a contested term. Specialist literature debates various viewpoints on the co ...

– was dominated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

(IRB) who rose to prominence via the organisation, having had restarted recruitment in 1909. These members feared that Home Rule's enactment would result in a broad, seemingly perpetual, contentment with the British Empire. Another militant group, the Irish Citizen Army

The Irish Citizen Army (), or ICA, was a paramilitary group first formed in Dublin to defend the picket lines and street demonstrations of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) against the police during the Great Dublin Lock ...

, was formed by trade unionists as a result of the Dublin Lock-out

The Dublin lock-out was a major industrial dispute between approximately 20,000 workers and 300 employers that took place in Dublin, Ireland. The dispute, lasting from 26 August 1913 to 18 January 1914, is often viewed as the most severe and s ...

of that year. The issue of Home Rule, appeared to some, as the basis of an "imminent civil war".

Although the Third Home Rule Bill was eventually enacted, the outbreak of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

resulted in its implementation being postponed for the war's duration. It was widely believed at the time that the war would not last more than a few months. The Irish Volunteers split. The vast majority – thereafter known as the National Volunteers

The National Volunteers were the majority faction of the Irish Volunteers that sided with Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond after the movement split over the question of the Volunteers' Ireland and World War I, role in World War I.

O ...

– enlisted in the British Army. The minority that objected – retaining the name – did so in accordance with separatist principles, official policy thus becoming "the abolition of the system of governing Ireland through Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle () is a major Government of Ireland, Irish government complex, conference centre, and tourist attraction. It is located off Dame Street in central Dublin.

It is a former motte-and-bailey castle and was chosen for its position at ...

and the British military power and the establishment of a National Government in its place"; the Volunteers believed that "England's difficulty" was "Ireland's opportunity".

Planning the Rising

The Supreme Council of the IRB met on 5 September 1914, just over a month after the British government haddeclared war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the public signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national govern ...

on Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. At this meeting, they elected to stage an uprising before the war ended and to secure help from Germany. Responsibility for the planning of the rising was given to Tom Clarke and Seán Mac Diarmada

Seán Mac Diarmada (27 January 1883 – 12 May 1916), also known as Seán MacDermott, was an Irish republican political activist and revolutionary leader. He was one of the seven leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916, which he helped to organ ...

. Patrick Pearse

Patrick Henry Pearse (also known as Pádraig or Pádraic Pearse; ; 10 November 1879 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish teacher, barrister, Irish poetry, poet, writer, Irish nationalism, nationalist, Irish republicanism, republican political activist a ...

, Michael Joseph O'Rahilly, Joseph Plunkett

Joseph Mary Plunkett ( Irish: ''Seosamh Máire Pluincéid''; 21 November 1887 – 4 May 1916) was an Irish republican, poet and journalist. As a leader of the 1916 Easter Rising, he was one of the seven signatories to the Proclamation of the I ...

and Bulmer Hobson

John Bulmer Hobson (14 January 1883 – 8 August 1969) was an Irish republican. He was a leading member of the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) before the Easter Rising in 1916.D.J. Hickey & J. E. Doherty, ''A New D ...

would assume general control of the Volunteers by March 1915.

In May 1915, Clarke and Mac Diarmada established a Military Council within the IRB, consisting of Pearse, Plunkett and Éamonn Ceannt – and soon themselves – to devise plans for a rising. The Military Council functioned independently and in opposition to those who considered a possible uprising inopportune. Volunteer Chief-of-Staff Eoin MacNeill supported a rising only if the British government attempted to suppress the Volunteers or introduce conscription in Ireland

Military conscription has never applied in Ireland (both Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland). The Defence Forces are the armed forces of the Republic of Ireland, and serves as an all-volunteer military. Irish neutrality means Ireland has b ...

, and if such a rising had some chance of success. Hobson and IRB President Denis McCullough held similar views as did much of the executive branches of both organisations.

The Military Council kept its plans secret, so as to prevent the British authorities from learning of the plans, and to thwart those within the organisation who might try to stop the rising. The secrecy of the plans was such that the Military Council largely superseded the IRB's Supreme Council with even McCullough being unaware of some of the plans, whereas the likes of MacNeill were only informed as the Rising rapidly approached. Although most Volunteers were oblivious to any plans their training increased in the preceding year. The public nature of their training heightened tensions with authorities, which, come the next year, manifested in rumours of the Rising. Public displays likewise existed in the espousal of anti-recruitment. The number of Volunteers also increased: between December 1914 and February 1916 the rank and file rose from 9,700 to 12,215. Although the likes of the civil servants were discouraged from joining the Volunteers, the organisation was permitted by law.

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, Roger Casement

Roger David Casement (; 1 September 1864 – 3 August 1916), known as Sir Roger Casement, CMG, between 1911 and 1916, was a diplomat and Irish nationalist executed by the United Kingdom for treason during World War I. He worked for the Britis ...

and John Devoy

John Devoy (, ; 3 September 1842 – 29 September 1928) was an Irish republican Rebellion, rebel and journalist who owned and edited ''The Gaelic American'', a New York weekly newspaper, from 1903 to 1928.

Devoy dedicated over 60 year ...

went to Germany and began negotiations with the German government and military. Casement – later accompanied by Plunkett – persuaded the Germans to announce their support for Irish independence in November 1914. Casement envisioned the recruitment of Irish prisoners of war, to be known as the Irish Brigade, aided by a German expeditionary force who would secure the line of the River Shannon

The River Shannon ( or archaic ') is the major river on the island of Ireland, and at in length, is the longest river in the British Isles. It drains the Shannon River Basin, which has an area of , – approximately one fifth of the area of I ...

, before advancing on the capital. Neither intention came to fruition, but the German military did agree to ship arms and ammunition to the Volunteers, gunrunning having become difficult and dangerous on account of the war.

In late 1915 and early 1916 Devoy had trusted couriers deliver approximately $100,000 from the American-based Irish Republican organization Clan na Gael

Clan na Gael (CnG) (, ; "family of the Gaels") is an Irish republican organization, founded in the United States in the late 19th and 20th centuries, successor to the Fenian Brotherhood and a sister organization to the Irish Republican Bro ...

to the IRB. In January 1916 the Supreme Council of the IRB decided that the rising would begin on Easter Sunday, 23 April 1916. On 5 February 1916 Devoy received a coded message from the Supreme Council of the IRB informing him of their decision to start a rebellion at Easter 1916: "We have decided to begin action on Easter Sunday. We must have your arms and munitions in Limerick between Good Friday and Easter Sunday. We expect German help immediately after beginning action. We might have to begin earlier."

Head of the Irish Citizen Army, James Connolly, was unaware of the IRB's plans, and threatened to start a rebellion on his own if other parties failed to act. The IRB leaders met with Connolly in Dolphin's Barn in January 1916 and convinced him to join forces with them. They agreed that they would launch a rising together at Easter and made Connolly the sixth member of the Military Council. Thomas MacDonagh would later become the seventh and final member.

The death of the old Fenian

The word ''Fenian'' () served as an umbrella term for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their affiliate in the United States, the Fenian Brotherhood. They were secret political organisations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries ...

leader Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa

Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa (; 4 September 1831 (baptised) – 29 June 1915)Con O'Callaghan Reenascreena Community Online (dead link archived at archive.org, 29 September 2014) was an Irish Fenian leader who was one of the leading members of t ...

in New York City in August 1915 was an opportunity to mount a spectacular demonstration. His body was sent to Ireland for burial in Glasnevin Cemetery

Glasnevin Cemetery () is a large cemetery in Glasnevin, Dublin, Ireland which opened in 1832. It holds the graves and memorials of several notable figures, and has a museum.

Location

The cemetery is located in Glasnevin, Dublin, in two part ...

, with the Volunteers in charge of arrangements. Huge crowds lined the route and gathered at the graveside. Pearse (wearing the uniform of the Irish Volunteers) made a dramatic funeral oration, a rallying call to republicans, which ended with the words " Ireland unfree shall never be at peace".

Build-up to Easter Week

In early April, Pearse issued orders to the Irish Volunteers for three days of "parades and manoeuvres" beginning on Easter Sunday. He had the authority to do this, as the Volunteers' Director of Organisation. The idea was that IRB members within the organisation would know these were orders to begin the rising, while men such as MacNeill and the British authorities would take it at face value.

On 9 April, the

In early April, Pearse issued orders to the Irish Volunteers for three days of "parades and manoeuvres" beginning on Easter Sunday. He had the authority to do this, as the Volunteers' Director of Organisation. The idea was that IRB members within the organisation would know these were orders to begin the rising, while men such as MacNeill and the British authorities would take it at face value.

On 9 April, the German Navy

The German Navy (, ) is part of the unified (Federal Defense), the German Armed Forces. The German Navy was originally known as the ''Bundesmarine'' (Federal Navy) from 1956 to 1995, when ''Deutsche Marine'' (German Navy) became the official ...

dispatched the SS ''Libau'' for County Kerry

County Kerry () is a Counties of Ireland, county on the southwest coast of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. It is bordered by two other countie ...

, disguised as the Norwegian ship ''Aud

The Australian dollar ( sign: $; code: AUD; also abbreviated A$ or sometimes AU$ to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; and also referred to as the dollar or Aussie dollar) is the official currency and legal tender of Au ...

''. It was loaded with 20,000 rifles, one million rounds of ammunition, and explosives. Casement also left for Ireland aboard the German submarine '' U-19''. He was disappointed with the level of support offered by the Germans and he intended to stop or at least postpone the rising. During this time, the Volunteers amassed ammunition from various sources, including the adolescent Michael McCabe.

On Wednesday 19 April, Alderman Tom Kelly, a Sinn Féin member of Dublin Corporation

Dublin Corporation (), known by generations of Dubliners simply as ''The Corpo'', is the former name of the city government and its administrative organisation in Dublin since the 1100s. Significantly re-structured in 1660–1661, even more si ...

, read out at a meeting of the corporation a document purportedly leaked from Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle () is a major Government of Ireland, Irish government complex, conference centre, and tourist attraction. It is located off Dame Street in central Dublin.

It is a former motte-and-bailey castle and was chosen for its position at ...

, detailing plans by the British authorities to shortly arrest leaders of the Irish Volunteers, Sinn Féin and the Gaelic League, and occupy their premises. Although the British authorities said the "Castle Document" was fake, MacNeill ordered the Volunteers to prepare to resist. Unbeknownst to MacNeill, the document had been forged

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compression (physics), compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die (manufacturing), die. Forging is often classif ...

by the Military Council to persuade moderates of the need for their planned uprising. It was an edited version of a real document outlining British plans in the event of conscription. That same day, the Military Council informed senior Volunteer officers that the rising would begin on Easter Sunday. However, it chose not to inform the rank-and-file, or moderates such as MacNeill, until the last minute.

The following day, MacNeill got wind that a rising was about to be launched and threatened to do everything he could to prevent it, short of informing the British. He and Hobson confronted Pearse, but refrained from decisive action as to avoiding instigating a rebellion of any kind; Hobson would be detained by Volunteers until the Rising occurred.

The ''SS Libau'' (disguised as the ''Aud'') and the ''U-19'' reached the coast of Kerry on Good Friday, 21 April. This was earlier than the Volunteers expected and so none were there to meet the vessels. The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

had known about the arms shipment and intercepted the ''SS Libau'', prompting the captain to scuttle the ship. Furthermore, Casement was captured shortly after he landed at Banna Strand

Banna Strand (Irish language, Gaeilge: Trá na Beannaí), also known as Banna Beach, is a beach in North Kerry, Ireland. It is an Atlantic Ocean beach extending from the Smallrock (Roc Beag) and Blackrock in the North to Carrahane at its south ...

.

When MacNeill learned that the arms shipment had been lost, he reverted to his original position. With the support of other leaders of like mind, notably Bulmer Hobson and The O'Rahilly, he issued a countermand to all Volunteers, cancelling all actions for Sunday. This countermanding order was relayed to Volunteer officers and printed in the Sunday morning newspapers. The order resulted in a delay to the rising by a day, and some confusion over strategy for those who took part.

British Naval Intelligence had been aware of the arms shipment, Casement's return, and the Easter date for the rising through radio messages between Germany and its embassy in the United States that were intercepted by the Royal Navy and deciphered in Room 40

Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (old building; officially part of NID25), was the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty during the First World War.

The group, which was formed in October 1914, began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, the ...

of the Admiralty. It is unclear how extensive Room 40's decryptions preceding the Rising were. On the eve of the Rising, John Dillon

John Dillon (4 September 1851 – 4 August 1927) was an Irish politician from Dublin, who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for over 35 years and was the last leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. By political disposition, Dillon was a ...

wrote to Redmond of Dublin being "full of most extraordinary rumours. And I have no doubt in my mind that the Clan men – are planning some devilish business – what it is I cannot make out. It may not come off – But you must not be surprised if something very unpleasant and mischievous happens this week".

The information was passed to the Under-Secretary for Ireland

The Under-Secretary for Ireland (Permanent Under-Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland) was the permanent head (or most senior civil servant) of the British administration in Ireland prior to the establishment of the Irish Free State in 192 ...

, Sir Matthew Nathan

Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Matthew Nathan (3 January 1862 – 18 April 1939) was a British soldier and colonial administrator, who variously served as the governor of Sierra Leone, Gold Coast, Hong Kong, Natal and Queensland. He was Under-Secre ...

, on 17 April, but without revealing its source; Nathan was doubtful about its accuracy. When news reached Dublin of the capture of the ''SS Libau'' and the arrest of Casement, Nathan conferred with the Lord Lieutenant

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibility ov ...

, Lord Wimborne. Nathan proposed to raid Liberty Hall, headquarters of the Citizen Army, and Volunteer properties at Father Matthew Park and at Kimmage, but Wimborne insisted on wholesale arrests of the leaders. It was decided to postpone action until after Easter Monday, and in the meantime, Nathan telegraphed the Chief Secretary, Augustine Birrell

Augustine Birrell KC (19 January 1850 – 20 November 1933) was a British Liberal Party politician, who was Chief Secretary for Ireland from 1907 to 1916. In this post, he was praised for enabling tenant farmers to own their property, and for ...

, in London seeking his approval. By the time Birrell cabled his reply authorising the action, at noon on Monday 24 April 1916, the Rising had already begun.

On the morning of Easter Sunday, 23 April, the Military Council met at Liberty Hall to discuss what to do in light of MacNeill's countermanding order. They decided that the Rising would go ahead the following day, Easter Monday, and that the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army would go into action as the 'Army of the Irish Republic'. They elected Pearse as president of the Irish Republic, and also as Commander-in-Chief of the army; Connolly became Commandant of the Dublin Brigade. That weekend was largely spent preparing rations and manufacturing ammunition and bombs. Messengers were then sent to all units informing them of the new orders.

The Rising in Dublin

Easter Monday

On the morning of Monday 24 April, about 1,200 members of the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army mustered at several locations in central Dublin. Among them were members of the all-female

On the morning of Monday 24 April, about 1,200 members of the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army mustered at several locations in central Dublin. Among them were members of the all-female Cumann na mBan

Cumann na mBan (; but in English termed The Irishwomen's Council), abbreviated C na mB, is an Irish republican women's paramilitary organisation formed in Dublin on 2 April 1914, merging with and dissolving Inghinidhe na hÉireann, and in 191 ...

. Some wore Irish Volunteer and Citizen Army uniforms, while others wore civilian clothes with a yellow Irish Volunteer armband, military hats, and bandolier

A bandolier / bandoleer or a bando is a pocketed belt (clothing), belt for holding either individual Cartridge (firearms), cartridges, belt (firearms), belts of ammunition or United States 40 mm grenades, grenades. It is usually slung sash-styl ...

s. They were armed mostly with rifles (especially 1871 Mausers), but also with shotguns, revolvers, a few Mauser C96

The Mauser C96 (''Construktion 96'') is a semi-automatic pistol that was originally produced by German arms manufacturer Mauser from 1896 to 1937. Unlicensed copies of the gun were also manufactured in Spain and China in the first half of the 20 ...

semi-automatic pistols, and grenades. The number of Volunteers who mobilised was much smaller than expected. This was due to MacNeill's countermanding order, and the fact that the new orders had been sent so soon beforehand. However, several hundred Volunteers joined the Rising after it began.

Shortly before midday, the rebels began to seize important sites in central Dublin. The rebels' plan was to hold Dublin city centre. This was a large, oval-shaped area bounded by two canals: the Grand to the south and the Royal

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family or Royalty (disambiguation), royalty

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Ill ...

to the north, with the River Liffey

The River Liffey (Irish language, Irish: ''An Life'', historically ''An Ruirthe(a)ch'') is a river in eastern Ireland that ultimately flows through the centre of Dublin to its mouth within Dublin Bay. Its major Tributary, tributaries include t ...

running through the middle. On the southern and western edges of this district were five British Army barracks. Most of the rebels' positions had been chosen to defend against counter-attacks from these barracks. The rebels took the positions with ease. Civilians were evacuated and policemen were ejected or taken prisoner. Windows and doors were barricaded, food and supplies were secured, and first aid posts were set up. Barricades were erected on the streets to hinder British Army movement.

A joint force of about 400 Volunteers and the Citizen Army gathered at Liberty Hall under the command of Commandant James Connolly. This was the headquarters battalion, and it also included Commander-in-Chief Patrick Pearse, as well as Tom Clarke, Seán Mac Diarmada and Joseph Plunkett

Joseph Mary Plunkett ( Irish: ''Seosamh Máire Pluincéid''; 21 November 1887 – 4 May 1916) was an Irish republican, poet and journalist. As a leader of the 1916 Easter Rising, he was one of the seven signatories to the Proclamation of the I ...

. They marched to the General Post Office

The General Post Office (GPO) was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969. Established in England in the 17th century, the GPO was a state monopoly covering the dispatch of items from a specific ...

(GPO) on O'Connell Street

O'Connell Street () is a street in the centre of Dublin, Ireland, running north from the River Liffey. It connects the O'Connell Bridge to the south with Parnell Street to the north and is roughly split into two sections bisected by Henry ...