Early Modern Irish Language on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the

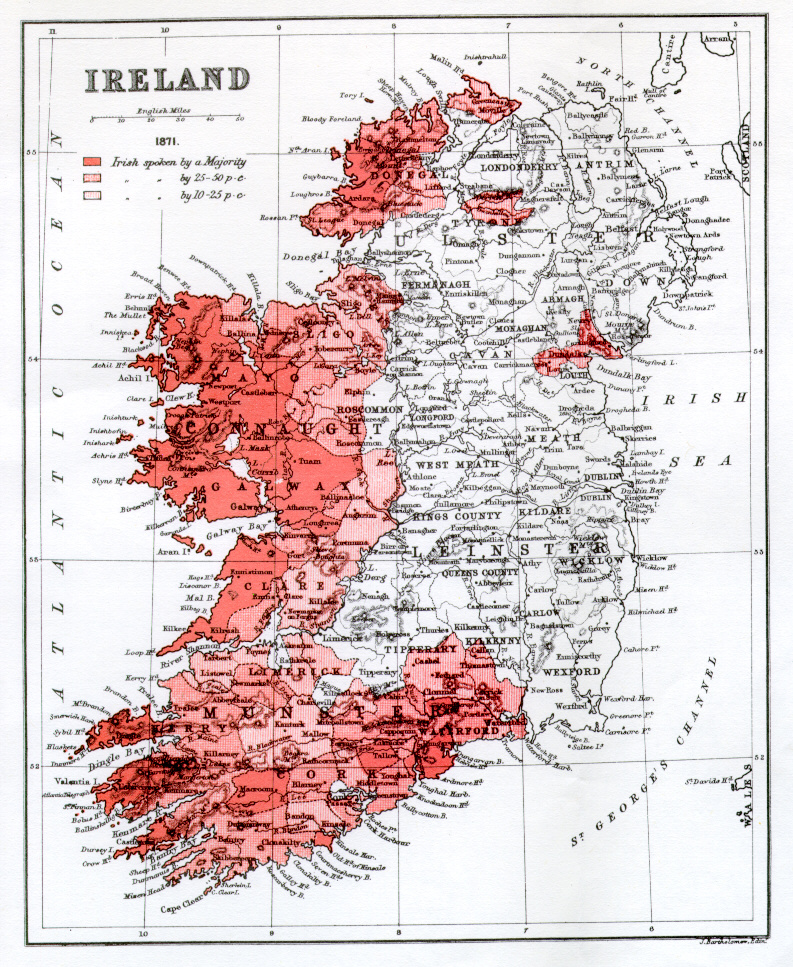

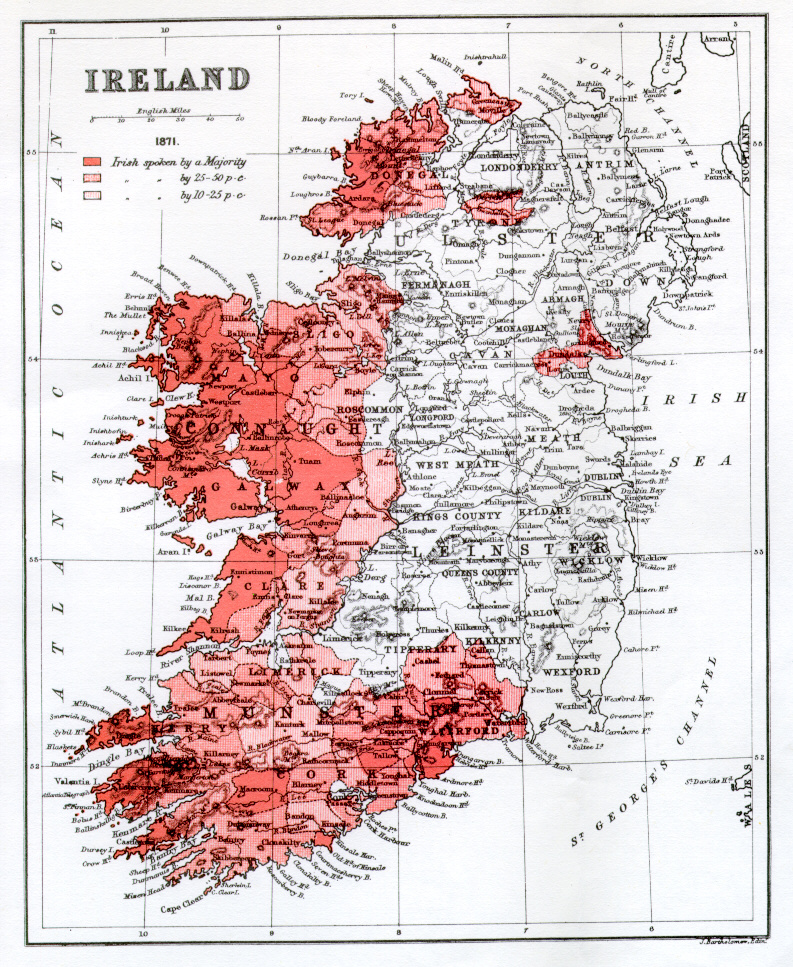

It is believed that Irish remained the majority tongue as late as 1800 but became a minority language during the 19th century. It is an important part of Irish nationalist identity, marking a cultural distance between Irish people and the English.

A combination of the introduction of state funded, though predominantly denominationally Church delivered, primary education (the National school (Ireland), National Schools), from 1831, in which Irish was omitted from the curriculum till 1878, and only then added as a curiosity, to be learnt after English, Latin, Greek and French,Erick Falc’Her-Poyroux. ’The Great Famine in Ireland: a Linguistic and Cultural Disruption. Yann Bévant. La Grande Famine en Irlande 1845-1850, PUR, 2014. halshs-01147770

It is believed that Irish remained the majority tongue as late as 1800 but became a minority language during the 19th century. It is an important part of Irish nationalist identity, marking a cultural distance between Irish people and the English.

A combination of the introduction of state funded, though predominantly denominationally Church delivered, primary education (the National school (Ireland), National Schools), from 1831, in which Irish was omitted from the curriculum till 1878, and only then added as a curiosity, to be learnt after English, Latin, Greek and French,Erick Falc’Her-Poyroux. ’The Great Famine in Ireland: a Linguistic and Cultural Disruption. Yann Bévant. La Grande Famine en Irlande 1845-1850, PUR, 2014. halshs-01147770

/ref> and in the absence of an authorised Irish Catholic bible () before 1981, resulting in instruction primarily in English, or Latin. The National school (Ireland), National Schools run by the Catholic Church discouraged its use until about 1890. The Great Famine (Ireland), Great Famine () hit a disproportionately high number of Irish speakers (who lived in the poorer areas heavily hit by famine deaths and emigration), translated into its rapid decline. Irish political leaders, such as Daniel O'Connell (, himself a native speaker), were also critical of the language, seeing it as "backward", with English the language of the future. Economic opportunities for most Irish people arose with the Second Industrial Revolution in the English-speaking British Empire and United States. Contemporary reports spoke of Irish-speaking parents actively discouraging their children from speaking the language, and encouraging the use of English instead. This stigma towards speaking Irish remained strong long after independence. It has been argued, however, that the sheer number of Irish speakers in the nineteenth century and their social diversity meant that both religious and secular authorities had to engage with them. This meant that Irish, rather than being marginalised, was an essential element in the modernization of Ireland, especially before the Great Famine of the 1840s. Irish speakers insisted on using the language in the law courts (even when they knew English), and it was common to employ interpreters. It was not unusual for magistrates, lawyers and jurors to employ their own knowledge of Irish. Fluency in Irish was often necessary in commercial matters. Political candidates and political leaders found the language invaluable. Irish was an integral part of the "devotional revolution" which marked the standardisation of Catholic religious practice, and the Catholic bishops (often partly blamed for the decline of the language) went to great lengths to ensure there was an adequate supply of Irish-speaking priests. Irish was widely and unofficially used as a language of instruction both in the local pay-schools (often called hedge schools) and in the National Schools. Even after the 1840s, Irish speakers could be found in all occupations and professions. The initial moves to reverse the decline of the language were championed by Anglo-Irish Protestants such as the linguist and clergyman William Neilson (Presbyterian minister), William Neilson, towards the end of the 18th century, and Samuel Ferguson; the major push occurred with the foundation by Douglas Hyde, the son of a Church of Ireland rector, of the Gaelic League () in 1893, which was a factor in launching the Irish Revival movement. The Gaelic league managed to reach 50,000 members by 1904 and also successfully pressured the government into allowing the Irish language as a language of instruction the same year. Leading supporters of Conradh included Pádraig Pearse and Éamon de Valera. The revival of interest in the language coincided with other cultural revivals, such as the foundation of the Gaelic Athletic Association and the growth in the performance of plays about Ireland in English, by playwrights including W. B. Yeats, John Millington Synge, J. M. Synge, Seán O'Casey and Augusta, Lady Gregory, Lady Gregory, with their launch of the Abbey Theatre. By 1901, only approximately 641,000 people spoke Irish with only just 20,953 of those speakers being monolingual Irish speakers; how many had emigrated is unknown, but it is probably safe to say that a larger number of speakers lived elsewhere This change in demographics can be attributed to the Great Famine as well as the increasing social pressure to speak English. Even though the Abbey Theatre playwrights wrote in English (and indeed some disliked Irish) the Irish language affected them, as it did all Irish English speakers. The version of English spoken in Ireland, known as Hiberno-English bears similarities in some grammatical idioms with Irish. Writers who have used Hiberno-English include J. M. Synge, Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde and more recently in the writings of Seamus Heaney, Paul Durcan, and Dermot Bolger. This national cultural revival of the late 19th century and early 20th century matched the growing Irish radicalism in Irish politics. Many of those, such as Pearse, de Valera, W. T. Cosgrave () and Ernest Blythe (), who fought to achieve Irish independence and came to govern the independent Irish Free State, first became politically aware through Conradh na Gaeilge. Douglas Hyde had mentioned the necessity of "de-anglicizing" Ireland, as a culture, cultural goal that was not overtly political. Hyde resigned from its presidency in 1915 in protest when the movement voted to affiliate with the separatist cause; it had been infiltrated by members of the secretive Irish Republican Brotherhood, and had changed from being a purely cultural group to one with radical nationalist aims. A Church of Ireland campaign to promote worship and religion in Irish was started in 1914 with the founding of Cumann Gaeilge na hEaglaise, Cumann Gaelach na hEaglaise (the Irish Guild of the Church). The Catholic Church also replaced its liturgies in Latin with Irish and English following the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s, and its first Bible was published in 1981. The hit song "Theme from Harry's Game, Theme from ''Harry's Game''" by County Donegal music group Clannad (musical group), Clannad, became the first song to appear on Britain's ''Top of the Pops'' with Irish lyrics in 1982. It has been estimated that there were around 800,000 monoglot Irish speakers in 1800, which dropped to 320,000 by the end of Great Irish Famine, the famine, and under 17,000 by 1911.

In July 2003, the Official Languages Act 2003, Official Languages Act was signed, declaring Irish an official language, requiring public service providers to make services available in the language, which affected advertising, signage, announcements, public reports, and more.

In 2007, Irish became an official working language of the European Union.

In July 2003, the Official Languages Act 2003, Official Languages Act was signed, declaring Irish an official language, requiring public service providers to make services available in the language, which affected advertising, signage, announcements, public reports, and more.

In 2007, Irish became an official working language of the European Union.

Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic ( ), is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family. It is a member of the Goidelic languages of the Insular Celtic sub branch of the family and is indigenous ...

begins with the period from the arrival of speakers of Celtic languages

The Celtic languages ( ) are a branch of the Indo-European language family, descended from the hypothetical Proto-Celtic language. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward Lhuyd in 1707, following Paul-Yve ...

in Ireland to Ireland's earliest known form of Irish, Primitive Irish

Primitive Irish or Archaic Irish (), also called Proto-Goidelic, is the oldest known form of the Goidelic languages, and the ancestor of all languages within this family.

This phase of the language is known only from fragments, mostly persona ...

, which is found in Ogham

Ogham (also ogam and ogom, , Modern Irish: ; , later ) is an Early Medieval alphabet used primarily to write the early Irish language (in the "orthodox" inscriptions, 4th to 6th centuries AD), and later the Old Irish language ( scholastic ...

inscriptions dating from the 3rd or 4th century AD. After the conversion to Christianity in the 5th century, Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic (, Ogham, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ; ; or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic languages, Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive written texts. It was used from 600 to 900. The ...

begins to appear as glosses

A gloss is a brief notation, especially a marginal or interlinear one, of the meaning of a word or wording in a text. It may be in the language of the text or in the reader's language if that is different.

A collection of glosses is a ''glossar ...

and other marginalia

Marginalia (or apostils) are marks made in the margin (typography), margins of a book or other document. They may be scribbles, comments, gloss (annotation), glosses (annotations), critiques, doodles, drolleries, or illuminated manuscript, ...

in manuscripts

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand or typewritten, as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in some indirect or automated way. More recently, the term has c ...

written in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, beginning in the 6th century. It evolved in the 10th century to Middle Irish

Middle Irish, also called Middle Gaelic (, , ), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of Late Old English and Early Middle English. The modern Goideli ...

. Early Modern Irish

Early Modern Irish () represented a transition between Middle Irish and Modern Irish. Its literary form, Classical Gaelic, was used in Ireland and Scotland from the 13th to the 18th century.

Classical Gaelic

Classical Gaelic or Classical Irish ( ...

represented a transition between Middle and Modern Irish

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic ( ), is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family. It is a member of the Goidelic languages of the Insular Celtic sub branch of the family and is indigenous ...

. Its literary form, Classical Gaelic

Early Modern Irish () represented a transition between Middle Irish and Irish language, Modern Irish. Its literary form, Classical Gaelic, was used in Ireland and Scotland from the 13th to the 18th century.

Classical Gaelic

Classical Gaelic or C ...

, was used by writers in both Ireland and Scotland until the 18th century, in the course of which slowly but surely writers began writing in the vernacular dialects, Ulster Irish

Ulster Irish ( or , ) is the variety of Irish language, Irish spoken in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster. It "occupies a central position in the Goidelic languages, Gaelic world made up of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man". Uls ...

, Connacht Irish

Connacht Irish () is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the province of Connacht.

Gaeltacht regions in Connacht are found in Counties Mayo (notably Tourmakeady, Achill Island and Erris) and Galway (notably in parts of Connemara a ...

, Munster Irish

Munster Irish (, ) is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the province of Munster. Gaeltacht regions in Munster are found in the Gaeltachtaí of the Dingle Peninsula in west County Kerry, in the Iveragh Peninsula in south Kerry, in ...

and Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

. As the number of hereditary poets and scribes dwindled under British rule in the early 19th century, Irish became a mostly spoken tongue with little written literature appearing in the language until the Gaelic Revival

The Gaelic revival () was the late-nineteenth-century national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including folklore, mythology, sports, music, arts, etc.). Irish had diminished as a sp ...

of the late 19th century. The number of speakers was also declining in this period with monoglot and bilingual speakers of Irish increasingly adopting only English: while Irish never died out, by the time of the Revival it was largely confined to the less Anglicised regions of the island, which were often also the more rural and remote areas. In the 20th and 21st centuries, Irish has continued to survive in Gaeltacht

A ( , , ) is a district of Ireland, either individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The districts were first officially recognised ...

regions and among a minority in other regions. It has once again come to be considered an important part of the island's culture and heritage, with efforts being made to preserve and promote it.

Early history

Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia (e. ...

may have arrived in Ireland between 2400 and 2000 BC with the spread of the Bell Beaker culture

The Bell Beaker culture, also known as the Bell Beaker complex or Bell Beaker phenomenon, is an archaeological culture named after the inverted-bell beaker drinking vessel used at the beginning of the European Bronze Age, arising from around ...

when around 90% of the contemporary Neolithic population was replaced by lineages related to the Yamnaya culture

The Yamnaya ( ) or Yamna culture ( ), also known as the Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, is a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archaeological culture of the region between the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Ural rivers (the Pontic–C ...

from the Pontic steppe

Pontic, from the Greek ''pontos'' (, ), or "sea", may refer to:

The Black Sea Places

* The Pontic colonies, on its northern shores

* Pontus (region), a region on its southern shores

* The Pontic–Caspian steppe, steppelands stretching from n ...

. The Beaker culture has been suggested as a candidate for an early Indo-European culture

Proto-Indo-European society is the reconstructed culture of Proto-Indo-Europeans, the ancient speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language, ancestor of all modern Indo-European languages. Historical linguistics combined with archaeological and ...

, specifically, as ancestral to proto-Celtic

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the hypothetical ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly Linguistic reconstruction, reconstructed throu ...

."Almagro-Gorbea – La lengua de los Celtas y otros pueblos indoeuropeos de la península ibérica", 2001 p.95. In Almagro-Gorbea, M., Mariné, M. and Álvarez-Sanchís, J. R. (eds) ''Celtas y Vettones'', pp. 115–121. Ávila: Diputación Provincial de Ávila. J. P. Mallory

James Patrick Mallory (born October 25, 1945) is an American archaeologist and Indo-Europeanist. Mallory is an emeritus professor at Queen's University, Belfast; a member of the Royal Irish Academy, and the former editor of the '' Journal of ...

proposed in 2013 that the Beaker culture was associated with a European branch of Indo-European dialects, termed "North-west Indo-European", ancestral to not only Celtic but also Italic, Germanic, and Balto-Slavic.J. P. Mallory, 'The Indo-Europeanization of Atlantic Europe', in ''Celtic From the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the Arrival of Indo–European in Atlantic Europe'', eds J. T. Koch and B. Cunliffe (Oxford, 2013), pp. 17–40

Primitive Irish

The earliest written form of the Irish language is known to linguists asPrimitive Irish

Primitive Irish or Archaic Irish (), also called Proto-Goidelic, is the oldest known form of the Goidelic languages, and the ancestor of all languages within this family.

This phase of the language is known only from fragments, mostly persona ...

. Primitive Irish is known only from fragments, mostly personal names, inscribed on stone in the Ogham

Ogham (also ogam and ogom, , Modern Irish: ; , later ) is an Early Medieval alphabet used primarily to write the early Irish language (in the "orthodox" inscriptions, 4th to 6th centuries AD), and later the Old Irish language ( scholastic ...

alphabet. The earliest of such inscriptions probably date from the 3rd or 4th century. Ogham inscriptions are found primarily in the south of Ireland as well as in Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

and Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

, where it was brought by settlers from Ireland to sub-Roman Britain

Sub-Roman Britain, also called post-Roman Britain or Dark Age Britain, is the period of late antiquity in Great Britain between the end of Roman rule and the founding of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The term was originally used to describe archae ...

, and in the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

.

Old Irish

Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic (, Ogham, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ; ; or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic languages, Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive written texts. It was used from 600 to 900. The ...

was the first written vernacular language north of the Alps, and it first appeared in the margins of Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand or typewritten, as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in some indirect or automated way. More recently, the term has ...

s as early as the 6th century. Old Irish can be divided into two periods: Early Old Irish, also called Archaic Irish (c. 7th century), and Old Irish (8th–9th century). One of the most notable Old Irish texts was the ''Senchas Már

''Senchas Már'' (Old Irish for "Great Tradition") is the largest collection of early Irish legal texts, compiled into a single group sometime in the 8th century, though individual tracts vary in date. These tracts were almost certainly written ...

,'' a series of early legal tracts that are alleged to "have been redacted from a pre-Christian original by Saint Patrick."

Stories of the Ulster Cycle

The Ulster Cycle (), formerly known as the Red Branch Cycle, is a body of medieval Irish heroic legends and sagas of the Ulaid. It is set far in the past, in what is now eastern Ulster and northern Leinster, particularly counties Armagh, Do ...

were written primarily in the Middle Irish period, but many of the heroes featured were initially described in Old Irish texts. Many early Irish literary texts, though recorded in manuscripts of the Middle Irish period (such as ''Lebor na hUidre

(, LU) or the Book of the Dun Cow (MS 23 E 25) is an Irish vellum manuscript dating to the 12th century. It is the oldest extant manuscript in Irish. It is held in the Royal Irish Academy and is badly damaged: only 67 leaves remain and many ...

'' and the Book of Leinster), are essentially Old Irish in character.

Middle Irish

Middle Irish

Middle Irish, also called Middle Gaelic (, , ), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of Late Old English and Early Middle English. The modern Goideli ...

is the form of Irish used from c. 900 to c. 1200; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old English and early Middle English. It is characterized by an increased amount of linguistic variation compared to the relatively uniform writing of Old Irish. In Middle Irish texts. writers blended together contemporary and older linguistic forms in the same text.

Middle Irish is the language of a large amount of literature, including the entire Ulster Cycle

The Ulster Cycle (), formerly known as the Red Branch Cycle, is a body of medieval Irish heroic legends and sagas of the Ulaid. It is set far in the past, in what is now eastern Ulster and northern Leinster, particularly counties Armagh, Do ...

.

Early Modern Irish

Early Modern Irish (c. 1200–1600) represents a transition betweenMiddle Irish

Middle Irish, also called Middle Gaelic (, , ), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of Late Old English and Early Middle English. The modern Goideli ...

and Modern Irish

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic ( ), is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family. It is a member of the Goidelic languages of the Insular Celtic sub branch of the family and is indigenous ...

. Its literary form, Classical Gaelic

Early Modern Irish () represented a transition between Middle Irish and Irish language, Modern Irish. Its literary form, Classical Gaelic, was used in Ireland and Scotland from the 13th to the 18th century.

Classical Gaelic

Classical Gaelic or C ...

, was used in Ireland and Scotland from the 13th to the 18th century. The grammar of Early Modern Irish is laid out in a series of grammatical Tract (literature), tracts written by native speakers and intended to teach the most cultivated form of the language to student bards, lawyers, doctors, administrators, monks, and so on in Ireland and Scotland.

Nineteenth and twentieth centuries

It is believed that Irish remained the majority tongue as late as 1800 but became a minority language during the 19th century. It is an important part of Irish nationalist identity, marking a cultural distance between Irish people and the English.

A combination of the introduction of state funded, though predominantly denominationally Church delivered, primary education (the National school (Ireland), National Schools), from 1831, in which Irish was omitted from the curriculum till 1878, and only then added as a curiosity, to be learnt after English, Latin, Greek and French,Erick Falc’Her-Poyroux. ’The Great Famine in Ireland: a Linguistic and Cultural Disruption. Yann Bévant. La Grande Famine en Irlande 1845-1850, PUR, 2014. halshs-01147770

It is believed that Irish remained the majority tongue as late as 1800 but became a minority language during the 19th century. It is an important part of Irish nationalist identity, marking a cultural distance between Irish people and the English.

A combination of the introduction of state funded, though predominantly denominationally Church delivered, primary education (the National school (Ireland), National Schools), from 1831, in which Irish was omitted from the curriculum till 1878, and only then added as a curiosity, to be learnt after English, Latin, Greek and French,Erick Falc’Her-Poyroux. ’The Great Famine in Ireland: a Linguistic and Cultural Disruption. Yann Bévant. La Grande Famine en Irlande 1845-1850, PUR, 2014. halshs-01147770/ref> and in the absence of an authorised Irish Catholic bible () before 1981, resulting in instruction primarily in English, or Latin. The National school (Ireland), National Schools run by the Catholic Church discouraged its use until about 1890. The Great Famine (Ireland), Great Famine () hit a disproportionately high number of Irish speakers (who lived in the poorer areas heavily hit by famine deaths and emigration), translated into its rapid decline. Irish political leaders, such as Daniel O'Connell (, himself a native speaker), were also critical of the language, seeing it as "backward", with English the language of the future. Economic opportunities for most Irish people arose with the Second Industrial Revolution in the English-speaking British Empire and United States. Contemporary reports spoke of Irish-speaking parents actively discouraging their children from speaking the language, and encouraging the use of English instead. This stigma towards speaking Irish remained strong long after independence. It has been argued, however, that the sheer number of Irish speakers in the nineteenth century and their social diversity meant that both religious and secular authorities had to engage with them. This meant that Irish, rather than being marginalised, was an essential element in the modernization of Ireland, especially before the Great Famine of the 1840s. Irish speakers insisted on using the language in the law courts (even when they knew English), and it was common to employ interpreters. It was not unusual for magistrates, lawyers and jurors to employ their own knowledge of Irish. Fluency in Irish was often necessary in commercial matters. Political candidates and political leaders found the language invaluable. Irish was an integral part of the "devotional revolution" which marked the standardisation of Catholic religious practice, and the Catholic bishops (often partly blamed for the decline of the language) went to great lengths to ensure there was an adequate supply of Irish-speaking priests. Irish was widely and unofficially used as a language of instruction both in the local pay-schools (often called hedge schools) and in the National Schools. Even after the 1840s, Irish speakers could be found in all occupations and professions. The initial moves to reverse the decline of the language were championed by Anglo-Irish Protestants such as the linguist and clergyman William Neilson (Presbyterian minister), William Neilson, towards the end of the 18th century, and Samuel Ferguson; the major push occurred with the foundation by Douglas Hyde, the son of a Church of Ireland rector, of the Gaelic League () in 1893, which was a factor in launching the Irish Revival movement. The Gaelic league managed to reach 50,000 members by 1904 and also successfully pressured the government into allowing the Irish language as a language of instruction the same year. Leading supporters of Conradh included Pádraig Pearse and Éamon de Valera. The revival of interest in the language coincided with other cultural revivals, such as the foundation of the Gaelic Athletic Association and the growth in the performance of plays about Ireland in English, by playwrights including W. B. Yeats, John Millington Synge, J. M. Synge, Seán O'Casey and Augusta, Lady Gregory, Lady Gregory, with their launch of the Abbey Theatre. By 1901, only approximately 641,000 people spoke Irish with only just 20,953 of those speakers being monolingual Irish speakers; how many had emigrated is unknown, but it is probably safe to say that a larger number of speakers lived elsewhere This change in demographics can be attributed to the Great Famine as well as the increasing social pressure to speak English. Even though the Abbey Theatre playwrights wrote in English (and indeed some disliked Irish) the Irish language affected them, as it did all Irish English speakers. The version of English spoken in Ireland, known as Hiberno-English bears similarities in some grammatical idioms with Irish. Writers who have used Hiberno-English include J. M. Synge, Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde and more recently in the writings of Seamus Heaney, Paul Durcan, and Dermot Bolger. This national cultural revival of the late 19th century and early 20th century matched the growing Irish radicalism in Irish politics. Many of those, such as Pearse, de Valera, W. T. Cosgrave () and Ernest Blythe (), who fought to achieve Irish independence and came to govern the independent Irish Free State, first became politically aware through Conradh na Gaeilge. Douglas Hyde had mentioned the necessity of "de-anglicizing" Ireland, as a culture, cultural goal that was not overtly political. Hyde resigned from its presidency in 1915 in protest when the movement voted to affiliate with the separatist cause; it had been infiltrated by members of the secretive Irish Republican Brotherhood, and had changed from being a purely cultural group to one with radical nationalist aims. A Church of Ireland campaign to promote worship and religion in Irish was started in 1914 with the founding of Cumann Gaeilge na hEaglaise, Cumann Gaelach na hEaglaise (the Irish Guild of the Church). The Catholic Church also replaced its liturgies in Latin with Irish and English following the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s, and its first Bible was published in 1981. The hit song "Theme from Harry's Game, Theme from ''Harry's Game''" by County Donegal music group Clannad (musical group), Clannad, became the first song to appear on Britain's ''Top of the Pops'' with Irish lyrics in 1982. It has been estimated that there were around 800,000 monoglot Irish speakers in 1800, which dropped to 320,000 by the end of Great Irish Famine, the famine, and under 17,000 by 1911.

Twenty-first century

In July 2003, the Official Languages Act 2003, Official Languages Act was signed, declaring Irish an official language, requiring public service providers to make services available in the language, which affected advertising, signage, announcements, public reports, and more.

In 2007, Irish became an official working language of the European Union.

In July 2003, the Official Languages Act 2003, Official Languages Act was signed, declaring Irish an official language, requiring public service providers to make services available in the language, which affected advertising, signage, announcements, public reports, and more.

In 2007, Irish became an official working language of the European Union.

Independent Ireland and the language

The independent Irish state was established in 1922 (Irish Free State 1922–1937; Éire, Ireland (Éire) from 1937, also described since 1949 as the Republic of Ireland). Although some Irish republicanism, Republican leaders had been committed language enthusiasts, the new state continued to use English as the language of administration, even in areas where over 80% of the population spoke Irish. There was some initial enthusiasm – a Dáil decree of March 1922 required that the Irish versions of names on all birth, death and marriage certificates would have to be used from July 1923. While the decree was passed unanimously, it was never implemented, probably because of the outbreak of the Irish Civil War. Those areas of the state where Irish had remained widespread were officially designated as Gaeltachtaí, where the language would initially be preserved and then ideally be expanded from across the whole island. The government refused to implement the 1926 recommendations of the Gaeltacht Commission, which included restoring Irish as the language of administration in such areas. As the role of the state grew, it therefore exerted tremendous pressure on Irish speakers to use English. This was only partly offset by measures which were supposed to support the Irish language. For instance, the state was by far the largest employer. A qualification in Irish was required to apply for state jobs. However, this did not require a high level of fluency, and few public employees were ever required to use Irish in the course of their work. On the other hand, state employees had to have perfect command of English and had to use it constantly. Because most public employees had a poor command of Irish, it was impossible to deal with them in Irish. If an Irish speaker wanted to apply for a grant, obtain electricity, or complain about being over-taxed, they would typically have had to do so in English. As late as 1986, a Bord na Gaeilge report noted "...the administrative agencies of the state have been among the strongest forces for Anglicisation in Gaeltacht areas". The new state also attempted to promote Irish through the school system. Some politicians claimed that the state would become predominantly Irish-speaking within a generation. In 1928, Irish was made a compulsory subject for the Intermediate Certificate (Ireland), Intermediate Certificate exams, and for the Irish Leaving Certificate, Leaving Certificate in 1934. However, it is generally agreed that the compulsory policy was clumsily implemented. The principal ideologue was Professor Timothy Corcoran (cultural historian), Timothy Corcoran of University College Dublin, who "did not trouble to acquire the language himself". From the mid-1940s onward the policy of teaching all subjects to English-speaking children through Irish was abandoned. In the following decades, support for the language was progressively reduced. Irish has undergone spelling and script reforms since the 1940s to simplify the language. The orthographic system was changed and the traditional Irish script fell into disuse. These reforms were met with a negative reaction and many people argued that these changes marked a loss of the Irish identity in order to appease language learners. Another reason for this backlash was that the reforms forced the current Irish speakers to relearn how to read Irish in order to adapt to the new system. It is disputed to what extent such professed language revivalists as de Valera genuinely tried to Gaelicisation, Gaelicise political life. Even in the first Dáil Éireann, few speeches were delivered in Irish, with the exception of formal proceedings. In the 1950s, An Caighdeán Oifigiúil ("The Official Standard") was introduced to simplify spellings and allow easier communication by different dialect speakers. By 1965 speakers in the Dáil regretted that those taught Irish in the traditional Irish script (the Irish type, ''Cló Gaedhealach'') over the previous decades were not helped by the recent change to the Latin script, the ''Cló Romhánach''. An ad-hoc "Language Freedom Movement" that was opposed to the compulsory teaching of Irish was started in 1966, but it had largely faded away within a decade. Overall, the percentage of people speaking Irish as a first language has decreased since independence, while the number of second-language speakers has increased. There have been some modern success stories in language preservation and promotion such as Gaelscoileanna the education movement, Official Languages Act 2003, TG4, RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta and Foinse. In 2005, Enda Kenny, formerly an Irish teacher, called for compulsory Irish to end at the Junior Certificate level, and for the language to be an optional subject for Irish Leaving Certificate, Leaving Certificate students. This provoked considerable comment, and Taoiseach Bertie Ahern argued that it should remain compulsory. Today, estimates of fully native speakers range from 40,000 to 80,000 people. In the republic, there are just over 72,000 people who use Irish as a daily language outside education, as well as a larger minority of the population who are fluent but do not use it on a daily basis. (While census figures indicate that 1.66 million people in the republic have some knowledge of the language, a significant percentage of these know only a little.) Smaller numbers of Irish speakers exist in Britain, Canada (particularly in Newfoundland and Labrador, Newfoundland), the United States of America and other countries. The most significant development in recent decades has been a rise in the number of urban Irish speakers. This community, which has been described as well-educated and largely middle-class, is largely based on an independent school system (called gaelscoileanna at primary level) which teaches entirely through Irish. These schools perform exceptionally well academically. An analysis of "feeder" schools (which supply students to tertiary level institutions) has shown that 22% of the Irish-medium schools sent all their students on to tertiary level, compared to 7% of English-medium schools. Given the rapid decline in the number of traditional speakers in theGaeltacht

A ( , , ) is a district of Ireland, either individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The districts were first officially recognised ...

it seems likely that the future of the language is in urban areas. It has been suggested that fluency in Irish, with its social and occupational advantages, may now be the mark of an urban elite. Others have argued, on the contrary, that the advantage lies with a middle-class elite which is, for cultural reasons, simply more likely to speak Irish. It has been estimated that the active Irish-language scene (mostly urban) may comprise as much as 10 per cent of Ireland's population.

Northern Ireland and the language

Since the partition of Ireland, the language communities in the Republic and Northern Ireland have taken radically different trajectories. While Irish is officially the first language of the Republic, in Northern Ireland the language only gained official status a century after partition with the Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act 2022. Irish in Northern Ireland declined rapidly during the 20th centuries, with its traditional Irish speaking-communities being replaced by learners and Gaelscoileanna. A recent development has been the interest shown by some Protestants in East Belfast who found out Irish was not an exclusively Catholic language and had been spoken by Protestants, mainly Presbyterians, in Ulster. In the 19th century fluency in Irish was at times a prerequisite to become a Presbyterian minister.References

{{Language histories History of the Irish language,