Dyer Lum on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dyer Daniel Lum (February 15, 1839 – April 6, 1893) was an American labor activist,

On May 3, 1886, the

On May 3, 1886, the  On November 10, 1887, Lingg committed suicide with a cigar-shaped explosive he had smuggled into his prison cell. Although journalists Charles Edward Russell and

On November 10, 1887, Lingg committed suicide with a cigar-shaped explosive he had smuggled into his prison cell. Although journalists Charles Edward Russell and

Lum was married and had two children, but later separated with his wife after their children grew to adulthood. In 1888, he met Voltairine de Cleyre. At the time, De Cleyre was in a relationship with Thomas Hamilton Garside, a man who Lum considered to be of a

Lum was married and had two children, but later separated with his wife after their children grew to adulthood. In 1888, he met Voltairine de Cleyre. At the time, De Cleyre was in a relationship with Thomas Hamilton Garside, a man who Lum considered to be of a

Communal Anarchy

(March 6, 1886, ''The Alarm'')

Evolution or Revolution

(March 20, 1886, ''Lucifer'') *"Drift" (March 20, 1886, ''The Alarm'') *"Inciting to Riot" (May 2, 1886, ''Lucifer'') *"The Knights of Labor" (June 19, 1886, ''Liberty'') *"Pen-Pictures of the Prisoners" (February 12, 1887, ''Liberty'') *"Anarchists Listen to the Siren Song" (April 23, 1887, ''Liberty'') *"Theoretical Methods" (July 16, 1887, ''Liberty'') *"Still in the Doleful Dumps" (July 30, 1887, ''Liberty'') *"The Polity of Knighthood" (February 11, 1888, ''The Alarm'') *"The Shield of Knighthood" (March 10, 1888, ''The Alarm'') *"To All My Readers" (April 28, 1888, ''The Alarm'') *"Correspondenzen" (May 12, 1888, ''Freiheit'') *"Greeting" (June 16, 1888, ''The Alarm'') *"The I.W.P.A" (July 14, 1888, ''The Alarm'') *"Trade Unions and Knights" (July 14, 1888, ''The Alarm'') *"Powderly's Allies" (October 13, 1888, ''The Alarm'') *"A Milestone in Social Progress" (September 1889, ''Carpenter'') *"Collectivist or Mutualist" (March 31, 1890, ''Individualist'') *"The Social Question" (May 1890, ''The Beacon'')

The Fiction of Natural Rights

(May 1890, ''Egoism'')

Why I Am a Social Revolutionist

(October 30, 1890, ''Twentieth Century'') *"August Spies" (September 3, 1891, ''Twentieth Century'') *"The Social Revolution" (October 24, 1891, ''The Commonweal'')

The Basis of Morals

(July 1897, ''The Monist'') *"Evolutionary Ethics" (July 1899, ''The Monist'')

Utah and Its People

' (1882, New York) *

Social Problems of Today

' (1886, New York) *

A Concise History of the Great Trial of the Chicago Anarchists in 1886

' (1886, Chicago) *

The Economics of Anarchy

' (1890) *''The Philosophy of Trade Unons'' (1892, New York) *''In Memoriam, Chicago, November 11, 1887: A Group of Unpublished Poems'' (1937, Berkeley Heights)

Anarchist Library page

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lum, Dyer D. 1839 births 1893 deaths 1890s suicides 19th-century American Buddhists 19th-century American economists 19th-century American male writers 19th-century American newspaper editors 19th-century American non-fiction writers Abolitionists from New York (state) American anarchist writers American anti-capitalists American Federation of Labor people American male non-fiction writers American male poets American people of Scottish descent American political journalists American political writers American spiritualists American syndicalists American trade union leaders Anarchists without adjectives Editors of Illinois newspapers Former Presbyterians Individualist anarchists Knights of Labor people Massachusetts Greenbacks Mutualists Socialist Labor Party of America politicians from Massachusetts Suicides in New York City Union army non-commissioned officers

economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social sciences, social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this ...

and political journalist

Political journalism is a broad branch of journalism that includes coverage of all aspects of politics and political science, although the term usually refers specifically to coverage of civil governments and political power.

Political journ ...

. He was a leading figure in the American anarchist movement of the 1880s and early 1890s, working within the organized labor movement and together with individualist theorists.

Born into an abolitionist family, Lum voluntarily enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, in which he fought for the abolition of slavery. After the war, he plied his trade as a bookbinder

Bookbinding is the process of building a book, usually in codex format, from an ordered stack of paper sheets with one's hands and tools, or in modern publishing, by a series of automated processes. Firstly, one binds the sheets of papers alon ...

in New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

and became involved in the nascent spiritualist movement, although he soon became skeptical of organized religion

Organized religion, also known as institutional religion, is religion in which belief systems and rituals are systematically arranged and formally established, typically by an official doctrine (or dogma), a hierarchical or bureaucratic leadership ...

and converted to Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

. At this time, he became involved in the growing political reform

Reform refers to the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The modern usage of the word emerged in the late 18th century and is believed to have originated from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement, which ...

movement, joining the Greenback Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an Political parties in the United States, American political party with an Competition law, anti-monopoly ideolog ...

and lobbying

Lobbying is a form of advocacy, which lawfully attempts to directly influence legislators or government officials, such as regulatory agency, regulatory agencies or judiciary. Lobbying involves direct, face-to-face contact and is carried out by va ...

for the institution of the eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses of working time.

The modern movement originated i ...

, as well as monetary

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are: med ...

and land reform

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

s.

By the early 1880s, he had become disillusioned by third party politics and moved towards revolutionary socialism

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revo ...

and individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism or anarcho-individualism is a collection of anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hi ...

. He joined the International Working People's Association

The International Working People's Association (IWPA), sometimes known as the "Black International," and originally named the "International Revolutionary Socialists", was an international anarchist political organization established in 1881 at a ...

(IWPA) and the Knights of Labor

The Knights of Labor (K of L), officially the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was the largest American labor movement of the 19th century, claiming for a time nearly one million members. It operated in the United States as well in ...

, within which he advocated for workers organization to push for economic reform and political revolution. Lum was deeply affected by the Haymarket affair

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886 at Haymarket Square (C ...

, as he was close friends with many of the defendants, including Albert Parsons, Adolph Fischer and Louis Lingg, the latter of whom he helped commit suicide in order to avoid execution. Lum's involvement in the affair became a source of criticism from Chicago anarchists, who accused him of displaying a cavalier attitude towards revolutionary martyr

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

dom, as well as the individualist Boston anarchists, who were alienated by his advocacy of revolutionary violence. Lum attempted to use his position to bridge the divide between the two factions, but was ultimately unsuccessful.

After Haymarket, he moved away from advocating violent revolution and became more closely involved in trade union organizing, which he thought provided a means through which to achieve a free association of producers and anarchy

Anarchy is a form of society without rulers. As a type of stateless society, it is commonly contrasted with states, which are centralized polities that claim a monopoly on violence over a permanent territory. Beyond a lack of government, it can ...

. He became an influential figure within the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

(AFL), encouraging its anti-political

Anti-politics is a term used to describe opposition to, or distrust in, traditional politics. It is closely connected with anti-establishment sentiment and public disengagement from formal politics. Anti-politics can indicate practices and ac ...

stance and practice of voluntary association

A voluntary group or union (also sometimes called a voluntary organization, common-interest association, association, or society) is a group of individuals who enter into an agreement, usually as volunteers, to form a body (or organization) to a ...

. At this time, he developed a political programme that called for the implementation of mutualist economics through workers' organization and revolutionary tactics. But by the early 1890s, he was overcome by depression and suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation, or suicidal thoughts, is the thought process of having ideas or ruminations about the possibility of dying by suicide.World Health Organization, ''ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics'', ver. 09/2020MB26.A Suicidal i ...

s. He committed suicide in 1893, months before the pardoning of the Haymarket defendants.

Early life and activism

Family and childhood

Dyer Daniel Lum was born on February 15, 1839, inGeneva, New York

Geneva is a City (New York), city in Ontario County, New York, Ontario and Seneca County, New York, Seneca counties in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is at the northern end of Seneca Lake (New York), Seneca Lake; all land port ...

. His paternal family was descended from the Scottish American

Scottish Americans or Scots Americans (; ) are Americans whose ancestry originates wholly or partly in Scotland. Scottish Americans are closely related to Scotch-Irish Americans, descendants of Ulster Scots, and communities emphasize and ce ...

settler Samuel Lum; and his maternal family were descended from Benjamin Tappan, a minuteman who fought in Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, and the father of the abolitionists Arthur

Arthur is a masculine given name of uncertain etymology. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur.

A common spelling variant used in many Slavic, Romance, and Germanic languages is Artur. In Spanish and Ital ...

and Lewis Tappan. Lum's parents recalled him being a rebellious child, who would often stay up at night to watch storm

A storm is any disturbed state of the natural environment or the atmosphere of an astronomical body. It may be marked by significant disruptions to normal conditions such as strong wind, tornadoes, hail, thunder and lightning (a thunderstor ...

s. Raised in the Presbyterian Church

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Christianity, Reformed Protestantism, Protestant tradition named for its form of ecclesiastical polity, church government by representative assemblies of Presbyterian polity#Elder, elders, known as ...

, as a child, Lum became skeptical of religion after he noticed that he had not been struck down for saying " damn" on a Sunday.

Military career

From an early age, Lum himself joined the abolitionist cause, going on to voluntarily enlist in aninfantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, military service, service, or administrative corps, specialisation.

In Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of l ...

of the Union Army after the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. During the war, he was captured and imprisoned twice by the Confederates, but both times managed to escape. He was then transferred from the infantry to the 14th New York Volunteer Regiment, in which he rose to the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

. At the time, he sincerely believed he was fighting for the abolition of slavery, but he later came to regret that he had risked his life "to spread cheap labor over the South."

Spiritualism, activism and journalism

Following the end of the war, Lum moved toNew England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

and found work as a bookbinder

Bookbinding is the process of building a book, usually in codex format, from an ordered stack of paper sheets with one's hands and tools, or in modern publishing, by a series of automated processes. Firstly, one binds the sheets of papers alon ...

, a common trade among anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or hierarchy, primarily targeting the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state w ...

of the period. Seeking knowledge about the afterlife

The afterlife or life after death is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's Stream of consciousness (psychology), stream of consciousness or Personal identity, identity continues to exist after the death of their ...

, he turned towards spiritualism

Spiritualism may refer to:

* Spiritual church movement, a group of Spiritualist churches and denominations historically based in the African-American community

* Spiritualism (beliefs), a metaphysical belief that the world is made up of at leas ...

and wrote on the subjects of science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

and religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

in the journal '' Banner of Light''. Within the spiritualist movement, he came into contact with various associated reform movements, including feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

and socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

. He became an active participant in reform campaigns, participating in the National Equal Rights Party's campaign to nominate Victoria Woodhull for President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

and petitioning against the declaration of a Christian state

A Christian state is a country that recognizes a form of Christianity as its official religion and often has a state church (also called an established church), which is a Christian denomination that supports the government and is supported by ...

.

But by 1873, he had become disillusioned with the superstition

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic (supernatural), magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly app ...

of the spiritualist movement, publicly denouncing it and joining the Free Religious Association

The Free Religious Association (FRA) was an American organization founded in 1867 to encourage free inquiry into religious matters and to promote what its founders called "free religion," which they understood to be the essence of religion that i ...

. In 1875, in search of spirituality

The meaning of ''spirituality'' has developed and expanded over time, and various meanings can be found alongside each other. Traditionally, spirituality referred to a religious process of re-formation which "aims to recover the original shape o ...

outside of organized religion

Organized religion, also known as institutional religion, is religion in which belief systems and rituals are systematically arranged and formally established, typically by an official doctrine (or dogma), a hierarchical or bureaucratic leadership ...

, he converted to Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

, which he saw as an egalitarian

Egalitarianism (; also equalitarianism) is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all h ...

and humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

philosophy. The Buddhist concept of Nirvana

Nirvana, in the Indian religions (Jainism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sikhism), is the concept of an individual's passions being extinguished as the ultimate state of salvation, release, or liberation from suffering ('' duḥkha'') and from the ...

influenced his later turn to revolutionary socialism

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revo ...

, as it provided a justification for revolutionary martyr

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

dom.

Political career

Greenback period

Towards the end of theReconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

, Lum moved to Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

. At this time, the beginning of the Long Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in Panic of 1873, 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1899, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been e ...

brought him into the nascent organized labor movement. He went into politics, joining the Greenback Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an Political parties in the United States, American political party with an Competition law, anti-monopoly ideolog ...

and participating in the 1876 Massachusetts gubernatorial election as the running mate of the abolitionist Wendell Phillips. He also served as the private secretary of union leader Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 11, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

, during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. The Great Railroad Strike of 187 ...

.

Lum's political campaigning caused him to lose his job, so in 1878, he moved to Washington, DC

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

in order to continued working as a bookbinder. He also found work as a political journalist

Political journalism is a broad branch of journalism that includes coverage of all aspects of politics and political science, although the term usually refers specifically to coverage of civil governments and political power.

Political journ ...

, writing articles for Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (; April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was an American individualist anarchist and self-identified socialist. Tucker was the editor and publisher of the American individualist anarchist periodical ''Liberty'' (1881–19 ...

's ''Radical Review'' and Patrick Ford's ''Irish World'', the latter of which helped him to forge ties between Irish republicans and American workers. In March 1879, he was appointed as a secretary for a congressional committee charged with investigating the " depression of labor." In 1880, he and Albert Parsons were also appointed to a national committee to lobby for the eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses of working time.

The modern movement originated i ...

in the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

. But despite their lobbying efforts, Congress was unmoved and their hope for reform started to whither. Lum's experience in national politics got him elected to the executive committee of the Greenback Party, where he pushed for improved labor rights

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, the ...

, monetary

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are: med ...

and land reform

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

, and the establishment of a third party in the United States.

From this position, he took a tour of the country, making a broad range of contacts, including socialists such as Albert Parsons in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

, Mormons

Mormons are a Religious denomination, religious and ethnocultural group, cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's d ...

in Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

and labor leader Denis Kearney in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

. From then on, Lum became a convinced anti-capitalist

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and Political movement, movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. Anti-capitalists seek to combat the worst effects of capitalism and to eventually replace capitalism ...

and, drawing from his abolitionist background, began campaigning for the abolition of "wage slavery

Wage slavery is a term used to criticize exploitation of labour by business, by keeping wages low or stagnant in order to maximize profits. The situation of wage slavery can be loosely defined as a person's dependence on wages (or a salary) f ...

". He set his sights on the abolition of rent, interest

In finance and economics, interest is payment from a debtor or deposit-taking financial institution to a lender or depositor of an amount above repayment of the principal sum (that is, the amount borrowed), at a particular rate. It is distinct f ...

, profit

Profit may refer to:

Business and law

* Profit (accounting), the difference between the purchase price and the costs of bringing to market

* Profit (economics), normal profit and economic profit

* Profit (real property), a nonpossessory inter ...

, which he saw as "the triple heads of the monster against which modern civilization is waging war." Lum held the Federal government of the United States

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct ...

responsible, drawing attention to its "class legislation" which had prioritised railroad construction and military training

Military education and training is a process which intends to establish and improve the capabilities of military personnel in their respective roles. Military training may be voluntary or compulsory duty. It begins with recruit training, proceed ...

, the latter of which made him consider whether armed revolution would be justified. He momentarily set his sights on the abolition of the two-party system

A two-party system is a political party system in which two major political parties consistently dominate the political landscape. At any point in time, one of the two parties typically holds a majority in the legislature and is usually referr ...

. Although sympathetic to the Republican Party's abolitionist roots, he felt it had since become a party of imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

and centralized government, while he considered the Democratic Party an unreliable partner for establishing social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

. He hoped that the Greenback Party could supplant them and realign American politics towards labor reform, but the party's nomination of the Republican James B. Weaver for the 1880 United States presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 2, 1880. Republican Party (United States), Republican nominee James A. Garfield defeated Winfield Scott Hancock of the Democratic Party (Uni ...

dashed his hopes.

On October 2, 1880, Lum left the Greenback Party, its executive committee and his post at ''Irish World'', and joined the Socialist Labor Party

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP)"The name of this organization shall be Socialist Labor Party". Art. I, Sec. 1 of thadopted at the Eleventh National Convention (New York, July 1904; amended at the National Conventions 1908, 1912, 1916, 1920, 192 ...

(SLP). But after the failure of both left-wing parties in the 1880 election, they collapsed, with many socialists beginning to move away from reformism

Reformism is a political tendency advocating the reform of an existing system or institution – often a political or religious establishment – as opposed to its abolition and replacement via revolution.

Within the socialist movement, ref ...

and electoralism towards insurrection

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

ary tactics. Revolutionary socialists subsequently broke away from the SLP and established the International Working People's Association

The International Working People's Association (IWPA), sometimes known as the "Black International," and originally named the "International Revolutionary Socialists", was an international anarchist political organization established in 1881 at a ...

(IWPA), which Lum himself joined in 1885.

Conversion to anarchism

During the early 1880s, Lum was radicalized towardsanti-statism

Anti-statism is an approach to social, economic or political philosophy that opposes the influence of the state over society. It emerged in reaction to the formation of modern sovereign states, which anti-statists considered to work against the ...

, culminating in his adoption of individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism or anarcho-individualism is a collection of anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hi ...

. In 1882, he published a pamphlet reporting on the federal government's repression of the Mormons' cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomy, autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned a ...

and voluntary association

A voluntary group or union (also sometimes called a voluntary organization, common-interest association, association, or society) is a group of individuals who enter into an agreement, usually as volunteers, to form a body (or organization) to a ...

s, which he argued had been done in order to extend American mining companies' holdings into Utah. His shift to individualist anarchism was inspired by the ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

'' economics of Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

, whose "law of equal liberty

The law of equal liberty is the fundamental precept of liberalism and socialism. Stated in various ways by many thinkers, it can be summarized as the view that all individuals must be granted the maximum possible freedom as long as that freedom do ...

" provided him with a basis for Lum's anarchist philosophy and whose advocacy of limited government

In political philosophy, limited government is the concept of a government limited in power. It is a key concept in the history of liberalism.Amy Gutmann, "How Limited Is Liberal Government" in Liberalism Without Illusions: Essays on Liberal ...

influenced him to argue against government intervention in labor affairs. He was also influenced by the mutualism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, ; ; 1809 – 19 January 1865) was a French anarchist, socialist, philosopher, and economist who founded mutualist philosophy and is considered by many to be the "father of anarchism". He was the first person to ca ...

, whose advocacy of mutual banking inspired the monetary reform policies of many American individualist anarchists, grouped around Benjamin Tucker's magazine ''Liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

''.

In his radicalisation, Lum had pursued both paths that reformers had taken towards anarchism during this period: he rejected reformism in favor of revolution, while also adopting a ''laissez-faire'' analysis of wage slavery, respectively acquainting himself with the strategy of anti-state socialism and the ideology of individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

. This "dual path to anarchism" influenced his belief in the necessity for a united anarchist movement, capable of providing a coherent ideology, strategy and organization for the labor movement. Lum considered the time he lived in to have presented a revolutionary situation for anarchists, due to the power vacuum

In political science and political history, the term power vacuum, also known as a power void, is an analogy between a physical vacuum to the political condition "when someone in a place of power, has lost control of something and no one has replac ...

left by the collapse of the left-wing parties, the failure of legislative form and the rapid growth of industrial unions

Industrial unionism is a trade union organising method through which all workers in the same Industry (economics), industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industrie ...

under the Knights of Labor

The Knights of Labor (K of L), officially the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was the largest American labor movement of the 19th century, claiming for a time nearly one million members. It operated in the United States as well in ...

. It was during this time that Lum first developed his anarchist political programme, which advocated for the organization of the working class, a refined revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

strategy, and a mutualist economic system.

Anarchist activism

In 1885, Lum gave infrequent lectures on revolutionary anarchism inNew Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound. With a population of 135,081 as determined by the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census, New Haven is List ...

, before moving to Port Jervis, New York. There he joined the Knights of Labor and began writing for a number of anarchist periodicals, including Moses Harman's free love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the State (polity), state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues we ...

magazine ''Lucifer'', Benjamin Tucker's individualist magazine ''Liberty'' and Albert Parsons' collectivist newspaper ''The Alarm

The Alarm are a Welsh rock band that formed in Rhyl, Wales in 1981. Initially formed as a punk band, the Toilets, in 1977 under lead vocalist Mike Peters, the group soon embraced arena rock and included marked influences from Welsh language ...

''. In ''Lucifer'' and ''Liberty'', he called on individualists to support the Knights of Labor and adopt revolutionary politics. While in ''The Alarm'', he wrote frequently about his ideas on workers' organization, revolutionary strategy and individualist economics, while also attempting to link the contemporary labor movement with earlier American revolutionary history.

By this time, popular unrest in the United States was reaching an apex. He predicted that this wave of unrest would soon erupt into social revolution

Social revolutions are sudden changes in the structure and nature of society. These revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed society, economy, culture, philosophy, and technology along with but more than just the political system ...

: "From the Atlantic to the Mississippi, the air seems charged with an exhilarating ingredient that fills men's thoughts with a new purpose."

Haymarket affair

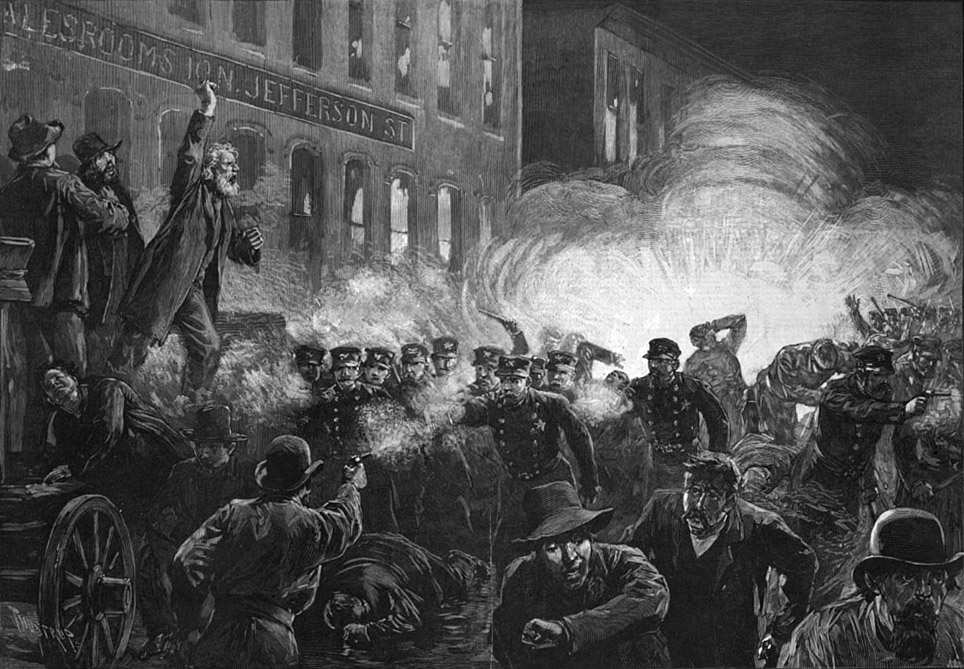

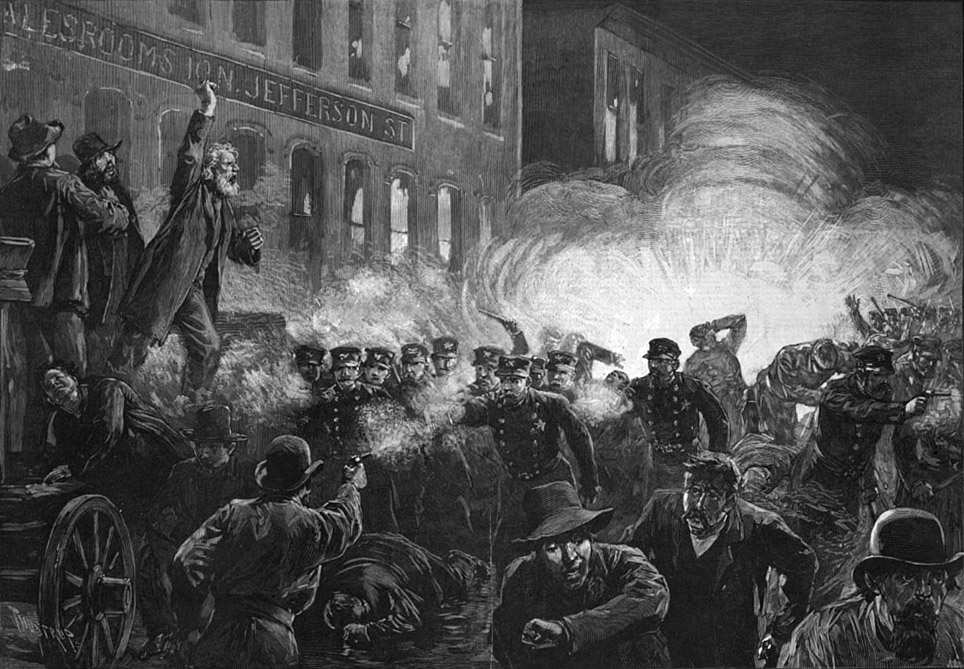

On May 3, 1886, the

On May 3, 1886, the Chicago Police Department

The Chicago Police Department (CPD) is the primary law enforcement agency of the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States, under the jurisdiction of the Chicago City Council. It is the second-largest Law enforcement in the United States#Local, ...

attempted to shut down a demonstration of striking workers in Haymarket Square. A bomb was thrown from the crowd and the police opened fire back, resulting in several people being killed. Lum quickly responded to the bombing with enthusiastic support, although he also expressed regret that it had only been an isolated, uncoordinated incident. Although the identity of the bomb thrower was never discovered, Lum himself believed the bomb had been thrown by an anarchist, rejecting later "puerile" conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political in motivation), when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

...

that alleged it had been thrown by an agent provocateur

An is a person who actively entices another person to commit a crime that would not otherwise have been committed and then reports the person to the authorities. They may target individuals or groups.

In jurisdictions in which conspiracy is a ...

.

Government repression swiftly followed the bombing, resulting in the closure of ''The Alarm'', Lum's primary platform within the IWPA. Albert Parsons, along with George Engel, Samuel Fielden, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, Oscar Neebe, Michael Schwab and August Spies, were arrested and brought to trial for what became known as the Haymarket affair

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886 at Haymarket Square (C ...

. Lum sold his bookbinding business in Port Jervis and moved to Chicago in order to support their defense campaign. He revived ''The Alarm'' under his own editorship and visited the defendants in the Cook County Jail on a daily basis. Lum staunchly defended the accused, believing them to have been innocent of the bombing. At the defendants' direction, he compiled the court records and trial transcripts into a book, in which he attempted to demonstrate that they were being convicted for their political beliefs. He also edited their autobiographies, which were published by the Knights of Labor, and organised their defense fund together with the Knights of Labor.

Although no evidence was ever produced of their culpability in the bombing, all eight men were found guilty. When Parsons asked Lum what he ought to do, given the sentence that faced him, Lum responded bluntly: "Die, Parsons." He convinced the sentenced men not to appeal for clemency, as it would "compromise their position". He later claimed that "no one helped them more than I to reject all proffers of mercy."

Lum collaborated with Burnette Haskell, together with whom he planned to unite the IWPA and SLP into a single "American Socialist Federation". But after allegations came out that they were planning to foment a revolution in 1889, on the centenary of the French Revolution, Lum was forced to narrow his strategy. Five days before their execution was scheduled to take place, he wrote in ''The Alarm'' that he believed the only thing that could save the Haymarket defendants from their fate would be an act of terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war aga ...

. Together with Robert Reitzel, Lum began planning such an attack, intending to blow up the jail in order to free them from their cells. Lum scheduled the attempt to take place on the day before they were due to be hanged. But as the day approached, the prisoners themselves called off the plot, telling Lum that they preferred to die. Lingg told him: "Work till we are dead. The time for vengeance will come later." Despite his desperation, Lum accepted that his comrades were about to die.

On November 10, 1887, Lingg committed suicide with a cigar-shaped explosive he had smuggled into his prison cell. Although journalists Charles Edward Russell and

On November 10, 1887, Lingg committed suicide with a cigar-shaped explosive he had smuggled into his prison cell. Although journalists Charles Edward Russell and Frank Harris

Frank Harris (14 February 1856 – 26 August 1931) was an Irish-American editor, novelist, short story writer, journalist and publisher, who was friendly with many well-known figures of his day.

Born in Ireland, he emigrated to the United State ...

hypothesised that it was Lingg's girlfriend who had smuggled him the dynamite, Voltairine de Cleyre believed it had been brought to him by Lum, recounting this version to her son Harry, who in turn told Agnes Inglis. Inglis didn't believe this version of events and instead hypothesised that it had been prison guards who had killed Lingg, but this counter-narrative was disregarded by Alexander Berkman, as the guards would have known Lingg was about to hang and considered him to have been "the kind of man who'd prefer to die by his own hand." Historian Paul Avrich

Paul Avrich (August 4, 1931 – February 16, 2006) was an American historian specializing in the 19th and early 20th-century anarchist movement in Russia and the United States. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for his ...

himself considered it to have been plausible that Lum could have carried this out, "to enable Lingg to cheat the hangman and at the same time enhance his heroic image". Citing Avrich, Frank H. Brooks also considered Lum to have been responsible for enabling Lingg's suicide.

On November 11, 1887, Parsons, Engel, Fischer and Spies were hanged. Lum had been a close friend of all five of the men, who were now considered martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

s of the anarchist movement. After their execution, he published biographies and poems about each of the men, as well as a history book about the affair. He also refused to shake hands with the Knights of Labor

The Knights of Labor (K of L), officially the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was the largest American labor movement of the 19th century, claiming for a time nearly one million members. It operated in the United States as well in ...

leader Terence V. Powderly, who had previously denounced the men as "bombthrowers".

Lum reported that he "shed no tears" for his fallen comrades and wrote that he was glad that the Haymarket affair had taken place. His apparently frivolous attitude towards the affair alienated him from others in the anarchist movement, with Spies' own wife Nina Van Zandt accusing him of "wishing their death", while Johann Most

Johann Joseph "Hans" Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American Social Democratic and then anarchist politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "propaganda of the deed" in the Un ...

and Lucy Parsons thought him an insensitive " hair splitter". Lum defended himself as having wanted to save "their honor to the cause" and insisted that the defendants had agreed with him. Shortly after the hanging, he wrote to Joseph Labadie

Charles Joseph Antoine Labadie (April 18, 1850 – October 7, 1933) was an American labor organizer, anarchist, Greenbacker, libertarian socialist, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist, and poet.

Biography

Early years

Jo Labadie was bo ...

: "I am very sorry you take their deaths so hard — can't you realize that it was nothing but an episode in our work? I do — Perhaps my nearness to them and seeing and feeling their enthusiasm gives me a different feeling." Lum himself actually regretted that he had not himself been with his comrades on the gallows. Union leader George A. Schilling wrote to him that " e trouble is you want to be with Engel, with Spies and Parsons, stand a crown upon your forehead and a bomb within your hand; you want to be a martyr and fill a martyr's grave."

Regrouping attempts

Rather than sparking a revolution, the Haymarket affair served to discredit Lum's revolutionary strategy. Benjamin Tucker's individualist group, already suspicious of such a strategy, distanced themselves from the revolutionary socialism of the Chicago anarchists, stressing the differences between it and their own ''laissez-faire'' anarchism. Lum thus set out to mend the divide between the individualist and socialist anarchists. He defended the Haymarket anarchists and challenged Tucker's rejection of revolutionary strategy, resulting in a polemical exchange breaking out between the two, as his position on revolutionary violence only alienated the individualists further. His "middle position" on the issue ofprivate property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental Capacity (law), legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which is owned by a state entity, and from Collective ownership ...

also drew ideological criticisms. In the pages of ''Liberty'', Victor Yarros called Lum's economic ideas "neither fish nor flesh". Tucker himself described his proposals as "amusing, and at the same time painful", telling Joseph Labadie

Charles Joseph Antoine Labadie (April 18, 1850 – October 7, 1933) was an American labor organizer, anarchist, Greenbacker, libertarian socialist, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist, and poet.

Biography

Early years

Jo Labadie was bo ...

that he had come to despise Lum. Lum himself returned fire at those contributors to ''Liberty'' whom he called the "dung-beetles", denouncing them for their excessive self-interest

Self-interest generally refers to a focus on the needs or desires (''interests'') of one's self. Most times, actions that display self-interest are often performed without conscious knowing. A number of philosophical, psychological, and economi ...

and lack of care for issues that affected wider society, particularly citing Tucker's defense of strikebreakers

A strikebreaker (sometimes pejoratively called a scab, blackleg, bootlicker, blackguard or knobstick) is a person who works despite an ongoing strike. Strikebreakers may be current employees ( union members or not), or new hires to keep the org ...

, who Lum described as "social traitors".

Meanwhile, the labor movement in Chicago was experiencing an organizational collapse. Despite Lum's protestations, many anarchists retreated into a defensive strategy, with a number of rank-and-file anarchists participating in local election

In many parts of the world, local elections take place to select office-holders in local government, such as mayors and councillors. Elections to positions within a city or town are often known as "municipal elections". Their form and conduct var ...

s, while the IWPA itself had effectively dissolved in the wake of the post-Haymarket repression. Despite the diminished influence of ''The Alarm'' and the Knights of Labor, Lum attempted to use his positions within both to regroup anarchists around the labor movement. Although he still believed in the inevitability of revolution, he realized that the situation after Haymarket required a different strategy and called for efforts to be refocused towards propagating the principles of anarchist socialism. He opened the columns of ''The Alarm'' to anarchists of all political tendencies, while continuing to promote his own ideology as editor. In the paper, he focused on the importance of the labor movement, arguing that the Knights of Labor, through its pursuit of workers' cooperatives and rejection of electoralism, could become a vehicle for an economic revolution.

In early 1888, he began publishing more radical articles, which caused issues with the Post Office and drew increasing levels of police harassment. In June 1888, he moved the printing offices of ''The Alarm'' to New York, where he received support from local German anarchists led by Johann Most

Johann Joseph "Hans" Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American Social Democratic and then anarchist politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "propaganda of the deed" in the Un ...

. There Lum continued printing calls for closer cooperation between the Knights of Labor and the anarchist movement, with articles on the organized labor movement eventually supplanting his earlier focus on mutualist economics, which alienating his remaining individualist readership. By February 1889, the paper had gone bankrupt and ceased publication. Finding himself unable to get his work published in ''Liberty'', Lum began writing for smaller publications like ''Individualist'' and ''Twentieth Century''. His attempts to revive the anarchist movement were ultimately unsuccessful, due to pervasive political repression, factionalism and widespread distrust in revolutionary anarchist ideology.

By 1890, Lum's attentions had turned towards the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

(AFL), as he saw its craft union

Craft unionism refers to a model of trade unionism in which workers are organised based on the particular craft or trade in which they work. It contrasts with industrial unionism, in which all workers in the same industry are organized into the sa ...

s as vehicles capable of moving society towards anarchism. That year, he published his pamphlet ''The Economics of Anarchy'', which advocated for mutual banks, land reform and workers' cooperatives, and was designed to be read in workers' studies groups. While he continued to believe in the inevitability of revolution, he now discarded revolutionary struggle in favor of union agitation, encouraged by the voluntary cooperation carried out by the AFL's unions in their campaign for the eight-hour day. In 1892, he developed his thoughts into a pamphlet titled "The Philosophy of Trade Unions", which was published by the AFL until 1914. Lum, alongside Joseph Labadie

Charles Joseph Antoine Labadie (April 18, 1850 – October 7, 1933) was an American labor organizer, anarchist, Greenbacker, libertarian socialist, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist, and poet.

Biography

Early years

Jo Labadie was bo ...

and August McCraith, committed himself to a long-term strategy of influencing trade unions towards anarchist principles. His abandonment of violent revolutionary strategy earned him criticism from Johann Most and other anarchist communists, who accused him of joining a "bourgeois scheme".

Later life and death

Relationship with Voltairine De Cleyre

Lum was married and had two children, but later separated with his wife after their children grew to adulthood. In 1888, he met Voltairine de Cleyre. At the time, De Cleyre was in a relationship with Thomas Hamilton Garside, a man who Lum considered to be of a

Lum was married and had two children, but later separated with his wife after their children grew to adulthood. In 1888, he met Voltairine de Cleyre. At the time, De Cleyre was in a relationship with Thomas Hamilton Garside, a man who Lum considered to be of a vain

Vain may refer to:

* Vain (band), an American glam metal band formed in 1986

* Vain (horse) (1966–1991), an Australian Thoroughbred racehorse

* Vain Stakes, an Australian Thoroughbred horse race

* Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia, a medical dis ...

and hedonistic

Hedonism is a family of philosophical views that prioritize pleasure. Psychological hedonism is the theory that all human behavior is motivated by the desire to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. As a form of egoism, it suggests that peopl ...

character. Lum attempted to warn De Cleyre away from Garside, but the two lovers ran away together; only a few months later, Garside abandoned De Cleyre. De Cleyre was deeply hurt by the rejection and fell into a depression. Lum was there to comfort her and became a stable presence in her life, as "her teacher

A teacher, also called a schoolteacher or formally an educator, is a person who helps students to acquire knowledge, competence, or virtue, via the practice of teaching.

''Informally'' the role of teacher may be taken on by anyone (e.g. w ...

, confidant

The confidant ( or ; feminine: confidante, same pronunciation) is a character in a story whom a protagonist confides in and trusts. Confidants may be other principal characters, characters who command trust by virtue of their position such as ...

and comrade

In political contexts, comrade means a fellow party member. The political use was inspired by the French Revolution, after which it grew into a form of address between socialists and workers. Since the Russian Revolution, popular culture in t ...

." The two had a lot in common: they both came from New England abolitionist families; they shared a keen interest in essay writing, poetry and translating from the French language

French ( or ) is a Romance languages, Romance language of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European family. Like all other Romance languages, it descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire. French evolved from Northern Old Gallo-R ...

; their anarchist philosophy blended individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

and socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

; they were both ascetic

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their pra ...

s and shared sympathy towards the working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

and immigrant communities; and they both suffered from mental illness

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness, a mental health condition, or a psychiatric disability, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. A mental disorder is ...

, particularly depression. Lum later wrote to De Cleyre that he had been attracted to her because of her "wild nature".

Although they spent a lot of time apart - Lum living in New York and De Cleyre in Philadelphia - and Lum was 27 years her senior, they came to fall in love with each other. By the following year, Lum was professing his love in poems written to De Cleyre, whom he called "Irene"; De Cleyre herself described her relationship with Lum as "one of the best fortunes of my life". Lum's relationship with De Cleyre was not just romantic, but also "intellectual and moral". De Cleyre's anarchist philosophy developed further under Lum's guidance, inspiring her to reject communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

and collectivist anarchism in favor of mutualism and voluntaryism

Voluntaryism (,"Voluntaryism"

. '' social novel Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not. Etymology The word "social" derives fro ...

together, in which they expounded their social and political philosophy, but it wasn't published during their lifetimes and the manuscript has been lost.

. '' social novel Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not. Etymology The word "social" derives fro ...

Decline and suicide

By 1892, Lum had become dissatisfied with his trade union activities, frustrated by hispoverty

Poverty is a state or condition in which an individual lacks the financial resources and essentials for a basic standard of living. Poverty can have diverse Biophysical environmen ...

, difficulties with publishers and his long-distance relationship with De Cleyre. At this time, a new cycle of popular protest had broken out, culminating in a series of labor strikes, the largest of which was the Homestead strike. Lum responded by renewing his revolutionary agitation. He gave revolutionary speeches to the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

, involved himself in bomb plots and organized black miners in Southwest Virginia

Southwest Virginia, often abbreviated as SWVA, is a mountainous region of Virginia in the westernmost part of the commonwealth. Located within the broader region of western Virginia, Southwest Virginia has been defined alternatively as all V ...

.

After Alexander Berkman's attempted assassination of the Homestead plant manager Henry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick (December 19, 1849 – December 2, 1919) was an American industrialist, financier, and art patron. He founded the H. C. Frick & Company coke manufacturing company, was chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company and played a major ...

, Lum publicly defended the attack, believing it was his duty to "share the effects of the counterblast his action may have provoked". At a public defense meeting in New York, Lum concluded that "the lesson for capitalists to learn is that workingmen are now growing so desperate that they not only make up their minds to die, but decide to take such men as Frick to St. Peter's gate with them." He also smuggled Berkman poison, in case he was sentenced to death. After Berkman was sentenced to 22 years in prison, he initiated a campaign for the reduction of his prison sentence.

By this time, Lum was himself making plans for a violent attack against the ruling class. Lum had written extensively to De Cleyre of his violent ideations, confessing that his anger would frequently consume him until it developed into hatred

Hatred or hate is an intense negative emotional response towards certain people, things or ideas, usually related to opposition or revulsion toward something. Hatred is often associated with intense feelings of anger, contempt, and disgust. Hat ...

. He confided to De Cleyre that he planned to carry out a suicide attack

A suicide attack (also known by a wide variety of other names, see below) is a deliberate attack in which the perpetrators knowingly sacrifice their own lives as part of the attack. These attacks are a form of murder–suicide that is ofte ...

to avenge the Haymarket martyrs. De Cleyre herself had come to reject violence and attempted to dissuade him, but Lum responded with derision, calling her "Moraline" and "Gusherine" and sarcastically saying "let us pray for the police here and the Tzar in Russia." He remained determined to fulfill his "pledge" to the Haymarket martyrs, writing to De Cleyre one final time, on February 5, 1892:

But Lum never carried out his planned attack, instead falling into a severe depression that left him unable to eat or sleep. Facing poverty

Poverty is a state or condition in which an individual lacks the financial resources and essentials for a basic standard of living. Poverty can have diverse Biophysical environmen ...

, he moved into a flophouse in Bowery

The Bowery () is a street and neighbourhood, neighborhood in Lower Manhattan in New York City, New York. The street runs from Chatham Square at Park Row (Manhattan), Park Row, Worth Street, and Mott Street in the south to Cooper Square at 4th ...

. As his insomnia

Insomnia, also known as sleeplessness, is a sleep disorder where people have difficulty sleeping. They may have difficulty falling asleep, or staying asleep for as long as desired. Insomnia is typically followed by daytime sleepiness, low ene ...

worsened and he became more desperate to get rest, he turned to alcohol

Alcohol may refer to:

Common uses

* Alcohol (chemistry), a class of compounds

* Ethanol, one of several alcohols, commonly known as alcohol in everyday life

** Alcohol (drug), intoxicant found in alcoholic beverages

** Alcoholic beverage, an alco ...

and opiate

An opiate is an alkaloid substance derived from opium (or poppy straw). It differs from the similar term ''opioid'' in that the latter is used to designate all substances, both natural and synthetic, that bind to opioid receptors in the brain ( ...

s. He also sought refuge in Buddhism, as well as the philosophical pessimism

Philosophical pessimism is a philosophical tradition that argues that life is not worth living and that non-existence is preferable to existence. Thinkers in this tradition emphasize that suffering outweighs pleasure, happiness is fleeting or u ...

of Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

. He briefly attempted to move to his family's home in Northampton, Massachusetts

The city of Northampton is the county seat of Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of Northampton (including its outer villages, Florence, Massachusetts, Florence and ...

, but under constant financial pressure, was forced to return. One of his friends recalled him, in September 1892, always wearing shabby clothes and carrying a large number of papers, "looking at no one, caring for nothing save the propaganda of Anarchism."

On the night of April 6, 1893, Lum went out for one last walk in New York City, before returning to his bedroom and swallowing a lethal dose of poison. According to De Cleyre, Lum "seized the unknown Monster, Death, with a smile on his lips." In her obituary on Lum, de Cleyre wrote that: "His early studies of Buddhism left a profound impress upon all his future concepts of life, and to the end his ideal of personal attainment was self-obliteration — Nirvana

Nirvana, in the Indian religions (Jainism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sikhism), is the concept of an individual's passions being extinguished as the ultimate state of salvation, release, or liberation from suffering ('' duḥkha'') and from the ...

."

Philosophy

Throughout his life, Lum drastically adapted his political strategy, moving fromlobbying

Lobbying is a form of advocacy, which lawfully attempts to directly influence legislators or government officials, such as regulatory agency, regulatory agencies or judiciary. Lobbying involves direct, face-to-face contact and is carried out by va ...

and third party politics to anti-political

Anti-politics is a term used to describe opposition to, or distrust in, traditional politics. It is closely connected with anti-establishment sentiment and public disengagement from formal politics. Anti-politics can indicate practices and ac ...

revolutionary activism and trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

organization. He also went through a large ideological evolution, from republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

and social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

to revolutionary socialism

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revo ...

and individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism or anarcho-individualism is a collection of anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hi ...

, resulting in his development of an eclectic political philosophy.

Lum's political philosophy synthesised elements from various different foundations within anarchist theory. Lum thought that a successful anarchist movement would require a "convincing and culturally-grounded" critique of political economy

Critique of political economy or simply the first critique of economy is a form of social critique that rejects the conventional ways of distributing resources. The critique also rejects what its advocates believe are unrealistic axioms, flawe ...

, which he proposed in the form of mutualism, and a way of putting such economic reforms into practice, proposing trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

organization and revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

strategy. He believed that the formation of a radical labor movement along such lines could attract enough workers that it could become a revolutionary force. Lum also elaborated on the evolutionary ethics that he believed underpinned anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

, anticipating the later works of Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist and geographer known as a proponent of anarchist communism.

Born into an aristocratic land-owning family, Kropotkin attended the Page Corps and later s ...

.

Lum drew from both American and European political thinkers, including Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, minister, abolitionism, abolitionist, and poet who led the Transcendentalism, Transcendentalist movement of th ...

and Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (born David Henry Thoreau; July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon sim ...

from the former, and Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, ; ; 1809 – 19 January 1865) was a French anarchist, socialist, philosopher, and economist who founded mutualist philosophy and is considered by many to be the "father of anarchism". He was the first person to ca ...

from the latter. Lum's anarchist ideology was grounded in the American radical tradition, rather than imported ideas from Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

or Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, and he consciously linked his anarchism with what he called the "American idea". Lum's philosophy thus represented a synthesis of American individualism and libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism is an anti-authoritarian and anti-capitalist political current that emphasises self-governance and workers' self-management. It is contrasted from other forms of socialism by its rejection of state ownership and from other ...

.

Mutualist economics

Lum was inspired by the economic theory of mutualism and defended individual autonomy and voluntary cooperation, outlining his economic views on these matters in ''The Economics of Anarchy''. Lum's own views on mutualism were based in an analysis of "wage slavery

Wage slavery is a term used to criticize exploitation of labour by business, by keeping wages low or stagnant in order to maximize profits. The situation of wage slavery can be loosely defined as a person's dependence on wages (or a salary) f ...

" and the reforms that would be necessary to abolish it. While grounding his economic theory in labor issues, Lum applied ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

'' economic theory to union organizing, drawing from the anti-statism