Duke Cunningham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Randall Harold "Duke" Cunningham (born December 8, 1941) is an American former politician,

Cunningham joined the

Cunningham joined the

Cunningham's visibility as a CNN commentator led several Republican leaders to approach him about running in what was then the 44th district, one of four

Cunningham's visibility as a CNN commentator led several Republican leaders to approach him about running in what was then the 44th district, one of four

On March 3, 2006, U.S. District Judge Larry A. Burns sentenced Cunningham to eight years and four months in prison. Federal prosecutors pushed for the maximum sentence of ten years, but Cunningham's defense lawyers argued that at 64 years old and with

On March 3, 2006, U.S. District Judge Larry A. Burns sentenced Cunningham to eight years and four months in prison. Federal prosecutors pushed for the maximum sentence of ten years, but Cunningham's defense lawyers argued that at 64 years old and with

The San Diego Union-Tribune's coverage of the Cunningham scandal

Washington Post Express interview with the authors of "The Wrong Stuff" about Cunningham and Washington's culture of corruption

PAC donors, Indiv donors, Personal Financial Disclosures, Campaign Disbursements, at PoliticalMoneyLine

* * *

Profile

at

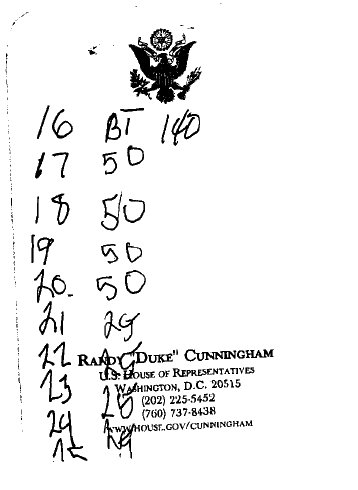

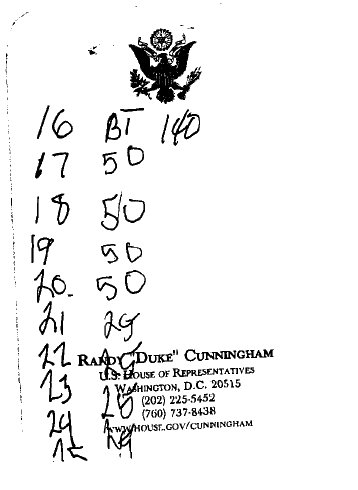

Prosecutor's allegations against Cunningham

* *

Cunningham's Sentencing Memorandum

February 17, 2006) , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Cunningham, Duke 1941 births American members of the Churches of Christ American politicians convicted of federal public corruption crimes American Vietnam War flying aces American people convicted of tax crimes Aviators from California California politicians convicted of crimes Living people Military personnel from California National University (California) alumni People from Shelby County, Missouri Politicians convicted of mail and wire fraud Politicians from Los Angeles Politicians from San Diego People pardoned by Donald Trump Recipients of the Air Medal Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) Recipients of the Silver Star Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from California United States Naval Aviators United States Navy officers University of Missouri alumni 21st-century members of the United States House of Representatives

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

veteran, fighter ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviation, military aviator credited with shooting down a certain minimum number of enemy aircraft during aerial combat; the exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ...

and convicted felon. A member of the Republican Party, Cunningham represented three California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

districts in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

from 1991 to 2005, and later served prison time for accepting bribes from defense contractor

A defense contractor is a business organization or individual that provides products or services to a military or intelligence department of a government. Products typically include military or civilian aircraft, ships, vehicles, weaponry, and ...

s.

Prior to his political career, Cunningham was an officer and pilot in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

for 20 years. Following the Vietnam War, during which he became one of just two Navy aviators to be confirmed as aces, Cunningham became an instructor at the Navy's Fighter Weapons School (better known as TOPGUN) and commanding officer of Fighter Squadron 126 (VF-126), a shore-based adversary squadron at NAS Miramar, California.

In 1990, Cunningham ran for the U.S. House of Representatives, defeating Democratic incumbent Jim Bates. He served in the House from 1991 to 2005, as the representative for California's 44th, 50th and 51st congressional district

Congressional districts, also known as electoral districts in other nations, are divisions of a larger administrative region that represent the population of a region in the larger congressional body. Countries with congressional districts includ ...

s. Cunningham resigned from the House on November 28, 2005, after pleading guilty to accepting at least $2.4 million in bribes and under-reporting

Under-reporting usually refers to some issue, incident, statistic, etc., that individuals, responsible agencies, or news media have not reported, or have reported as less than the actual level or amount. Under-reporting of crimes, for example, make ...

his taxable income

Taxable income refers to the base upon which an income tax system imposes tax. In other words, the income over which the government imposed tax. Generally, it includes some or all items of income and is reduced by expenses and other deductions. T ...

for 2004. He was sentenced to eight years and four months in prison and was ordered to pay $1.8 million in restitution

Restitution and unjust enrichment is the field of law relating to gains-based recovery. In contrast with damages (the law of compensation), restitution is a claim or remedy requiring a defendant to give up benefits wrongfully obtained. Liability ...

. On June 4, 2013, Cunningham completed his prison sentence. He was granted a conditional pardon by President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

in 2021.

Early life and education

Cunningham was born inLos Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

, California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, to Randall and Lela Cunningham on December 8, 1941, one day after the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

. His father was a truck driver for Union Oil at the time.California Birth certificate 41-118503 Around 1945, the family moved to Fresno

Fresno (; ) is a city in the San Joaquin Valley of California, United States. It is the county seat of Fresno County, California, Fresno County and the largest city in the greater Central Valley (California), Central Valley region. It covers a ...

, where Cunningham's father purchased a gas station

A filling station (also known as a gas station [] or petrol station []) is a facility that sells fuel and engine lubricants for motor vehicles. The most common fuels sold are gasoline (or petrol) and diesel fuel.

Fuel dispensers are used to ...

. In 1953, they moved to rural Shelbina, Missouri

Shelbina is a city in southern Shelby County, Missouri, United States. The population was 1,613 at the 2020 census.

History

Shelbina was platted in 1857 when the railroad was extended to that point. The name "Shelbina" is derived from Shelby C ...

, where his parents purchased and managed the five-and-dime Cunningham Variety Store.

Cunningham graduated from Shelbina High School in 1959. He attended Kirksville Teacher's College for one year, before transferring to the University of Missouri

The University of Missouri (Mizzou or MU) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Columbia, Missouri, United States. It is Missouri's largest university and the flagship of the four-campus Univers ...

in Columbia. Cunningham graduated with a bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Medieval Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six years ...

in education

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education als ...

and physical education

Physical education is an academic subject taught in schools worldwide, encompassing Primary education, primary, Secondary education, secondary, and sometimes tertiary education. It is often referred to as Phys. Ed. or PE, and in the United Stat ...

in 1964; he obtained his MA in education the following year. He later earned an MBA

A Master of Business Administration (MBA) is a professional degree focused on business administration. The core courses in an MBA program cover various areas of business administration; elective courses may allow further study in a particular a ...

from National University

A national university is mainly a university created or managed by a government, but which may also at the same time operate autonomously without direct control by the state. In the United States, the term "national university" connotes the highe ...

.

He was hired as a physical education teacher and swimming coach at Hinsdale Central High School, where he stayed for one year. Two members of his swim team competed in the 1968 Summer Olympics

The 1968 Summer Olympics (), officially known as the Games of the XIX Olympiad () and officially branded as Mexico 1968 (), were an international multi-sport event held from 12 to 27 October 1968, in Mexico City, Mexico. These were the first Ol ...

, where they earned a gold and a silver medal.

Military service

Cunningham joined the

Cunningham joined the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

in 1967. During his service, Cunningham and his Navigator/Radar Intercept Officer (RIO) William P. Driscoll became the only Navy aces

An ace is a playing card.

Ace(s), ACE(S) and variants may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Awards

* ACE Awards (Award for Cable Excellence)

Comics

* ''Ace Comics'', a 1937-1959 comic book series

* Ace Magazines (comics), a 1940- ...

in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, flying an F-4 Phantom II

The McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II is an American tandem two-seat, twin-engine, all-weather, long-range supersonic jet interceptor and fighter-bomber that was developed by McDonnell Aircraft for the United States Navy.Swanborough and Bower ...

from aboard aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

. He and Driscoll recorded five aerial victories against North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; ; VNDCCH), was a country in Southeast Asia from 1945 to 1976, with sovereignty fully recognized in 1954 Geneva Conference, 1954. A member of the communist Eastern Bloc, it o ...

ese MiG-21

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 (; NATO reporting name: Fishbed) is a supersonic jet aircraft, jet fighter aircraft, fighter and interceptor aircraft, designed by the Mikoyan, Mikoyan-Gurevich OKB, Design Bureau in the Soviet Union. Its nicknames in ...

and MiG-17

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17 (; NATO reporting name: Fresco) is a high-subsonic fighter aircraft produced in the Soviet Union from 1952 and was operated by air forces internationally. The MiG-17 was license-built in China as the Shenyang J-5 an ...

aircraft between January and May 1972, including three kills in one flight (earning them the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Naval Service's second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is equivalent to the Army ...

).

In the final engagement, Cunningham downed a MiG-17, which was supposedly piloted by "Colonel Toon", a mythical North Vietnam Air Force fighter ace loosely based on a North Vietnamese pilot from the 921st Fighter Regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, military service, service, or administrative corps, specialisation.

In Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of l ...

named Nguyễn Văn Cốc. It was later revealed by historians there was no such Colonel Toon and the story was fabricated by Cunningham himself. Văn Cốc retired from the Vietnamese People's Air Force in 2002.

While returning to the carrier after the final shoot-down, Cunningham and Driscoll were forced to eject from their F-4 over water near Nam Định

Nam Định () is the capital city of Nam Định province in the Red River Delta of the Northern Vietnam.

History

From August 18–20 of each year, there is a festival held in Nam Định called the Cố Trạch. This celebration honors Gener ...

after the aircraft was fatally damaged by a SA-2 surface-to-air missile, but they were rescued by Navy helicopter.

After returning to the U.S. from Vietnam in 1972, Cunningham became an instructor at the U.S. Navy's Fighter Weapons School (TOPGUN) at Naval Air Station Miramar in San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

. He was reportedly nearly court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

ed for allegedly breaking into his commanding officer's office to compare his records and fitness reports with those of his colleagues—a charge denied by Cunningham but supported by two of his superior officers at the time. Cunningham served tours with VF-154, United States Seventh Fleet

The Seventh Fleet is a numbered fleet of the United States Navy. It is headquartered at U.S. Fleet Activities Yokosuka, in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. It is part of the United States Pacific Fleet. At present, it is the largest of the ...

, and as executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization.

In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer ...

/commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or commander, or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually give ...

of the shore-based adversary squadron VF-126. In 1987, he was featured on the PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

broadcast of the ''NOVA

A nova ( novae or novas) is a transient astronomical event that causes the sudden appearance of a bright, apparently "new" star (hence the name "nova", Latin for "new") that slowly fades over weeks or months. All observed novae involve white ...

'' special "Top Gun And Beyond", during which he recounted his engagement with the North Vietnamese fighter pilot thought to be the mythical "Colonel Toon".

Cunningham retired from the Navy with the final rank of commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

in 1987, settling in Del Mar, a suburb of San Diego. He became nationally known as a CNN

Cable News Network (CNN) is a multinational news organization operating, most notably, a website and a TV channel headquartered in Atlanta. Founded in 1980 by American media proprietor Ted Turner and Reese Schonfeld as a 24-hour cable ne ...

commentator on naval aircraft in the run-up to the Persian Gulf War

, combatant2 =

, commander1 =

, commander2 =

, strength1 = Over 950,000 soldiers3,113 tanks1,800 aircraft2,200 artillery systems

, page = https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GAOREPORTS-PEMD-96- ...

.

Political career

Cunningham's visibility as a CNN commentator led several Republican leaders to approach him about running in what was then the 44th district, one of four

Cunningham's visibility as a CNN commentator led several Republican leaders to approach him about running in what was then the 44th district, one of four congressional district

Congressional districts, also known as electoral districts in other nations, are divisions of a larger administrative region that represent the population of a region in the larger congressional body. Countries with congressional districts includ ...

s in San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

. The district had been held for eight years by Democrat Jim Bates, and was considered the most Democratic district in the San Diego area. However, Bates was bogged down in a scandal involving charges of sexual harassment

Sexual harassment is a type of harassment based on the sex or gender of a victim. It can involve offensive sexist or sexual behavior, verbal or physical actions, up to bribery, coercion, and assault. Harassment may be explicit or implicit, wit ...

. Cunningham won the Republican nomination in 1990 and hammered Bates about the scandal, promising to be "a congressman we can be proud of." He won by just one percentage point, giving Republicans full representation of the San Diego area for only the second time since the city was split into two districts after the 1960 census.

Cunningham's status as a Vietnam war hero made him a sought-after source, by colleagues and the media, in the debate on whether to use military force against Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

in the lead up to the first Gulf War

, combatant2 =

, commander1 =

, commander2 =

, strength1 = Over 950,000 soldiers3,113 tanks1,800 aircraft2,200 artillery systems

, page = https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GAOREPORTS-PEMD-96- ...

. Guy Vander Jagt

Guy Adrian Vander Jagt ( ; August 26, 1931 – June 22, 2007) was a Republican politician from Michigan. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives and Chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee.

Vander Jagt was desc ...

of Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

, longtime chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee

The National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC) is the United States Republican Party, Republican Hill committee which works to elect Republicans to the United States House of Representatives.

The NRCC was formed in 1866, when the Repub ...

, said that Cunningham had considerable "drawing power" and was treated as a celebrity by his fellow Republicans.

After the 1990 census, redistricting renumbered the 44th district as the 51st and created the 50th district, splitting off a significant portion of San Diego County

San Diego County (), officially the County of San Diego, is a county in the southwest corner of the U.S. state of California, north to its border with Mexico. As of the 2020 census, the population was 3,298,634; it is the second-most populous ...

. At the same time, the 51st added several areas of heavily Republican North San Diego County. The new district included the home of Bill Lowery, a fellow Republican who had represented most of the other side of San Diego for the past 12 years. They faced one another in the Republican primary. Despite Lowery's seniority, his involvement in the House banking scandal hurt him. As polls showed Cunningham with a substantial lead, Lowery dropped out of the primary race, effectively handing Cunningham the nomination. Cunningham breezed to victory in November.

Even though the district (renumbered as the 50th after the 2000 census) was not nearly as conservative as the other two Republican-held districts in the San Diego area, Cunningham was re-elected six times with no less than 55 percent of the vote.

Cunningham was a member of the Appropriations and Intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

committees, and chaired the House Intelligence Subcommittee on Human Intelligence Analysis and Counterintelligence during the 109th Congress

The 109th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives, from January 3, 2005, to January 3, 2007, du ...

. He was considered a leading Republican expert on national security

National security, or national defence (national defense in American English), is the security and Defence (military), defence of a sovereign state, including its Citizenship, citizens, economy, and institutions, which is regarded as a duty of ...

issues. He was also a champion of education, using his position on the Appropriations Education Subcommittee to steer federal dollars to schools in San Diego. After surgery for prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is the neoplasm, uncontrolled growth of cells in the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system below the bladder. Abnormal growth of the prostate tissue is usually detected through Screening (medicine), screening tests, ...

in 1998, he became a champion of early testing for the disease.

Cunningham was known for making controversial comments. For example:

* Making a comment about gay Congressman Barney Frank

Barnett Frank (born March 31, 1940) is a retired American politician. He served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts from 1981 to 2013. A Democratic Party (United States), Democrat, Frank served as chairman of th ...

, where he called the rectal examination

Digital rectal examination (DRE), also known as a prostate exam (), is an internal examination of the rectum performed by a healthcare provider.

Prior to a 2018 report from the United States Preventive Services Task Force, a digital exam was a c ...

for prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is the neoplasm, uncontrolled growth of cells in the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system below the bladder. Abnormal growth of the prostate tissue is usually detected through Screening (medicine), screening tests, ...

"just not natural, unless maybe you're Barney Frank".

* Displaying his middle finger to a constituent and "for emphasis, houtingthe two-word meaning of his one-finger salute" during an argument over military spending.

* Suggesting that the Democratic House leadership should be "lined up and shot"—a call he had previously made about Vietnam War protesters

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's fifteenth-most populous coun ...

.

* Referring to gay soldiers as "homo

''Homo'' () is a genus of great ape (family Hominidae) that emerged from the genus ''Australopithecus'' and encompasses only a single extant species, ''Homo sapiens'' (modern humans), along with a number of extinct species (collectively called ...

s" on the floor of the House of Representatives when he said backers of an environmental amendment were "the same people that would ... put homos in the military." He later apologized for his comments.

Cunningham said that "I cut my own rudder" on issues, He was often compared by liberal interest groups

An interest group or an advocacy group is a body which uses various forms of advocacy in order to influence public opinion and/or policy.

Interest group may also refer to:

* Learned society

* Special interest group, a group of individuals sharing ...

to former congressman Bob Dornan; both were former military pilots, and both spoke out against perceived enemies. In 1992, Cunningham, along with Dornan and fellow San Diego Republican Duncan L. Hunter, challenged the patriotism of then-Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

before a near-empty House chamber, but still viewed by C-SPAN

Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN ) is an American Cable television in the United States, cable and Satellite television in the United States, satellite television network, created in 1979 by the cable television industry as a Non ...

viewers.

In September 1996, Cunningham criticized President Clinton for appointing judges who were "soft on crime". "We must get tough on drug dealers," he said, adding that "those who peddle destruction on our children must pay dearly". He favored stiff drug penalties and voted for the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

for major drug dealer

A drug is any chemical substance other than a nutrient or an essential dietary ingredient, which, when administered to a living organism, produces a biological effect. Consumption of drugs can be via inhalation, injection, smoking, ingestio ...

s.

Four months later, his son Todd was arrested for helping to transport of marijuana

Cannabis (), commonly known as marijuana (), weed, pot, and ganja, List of slang names for cannabis, among other names, is a non-chemically uniform psychoactive drug from the ''Cannabis'' plant. Native to Central or South Asia, cannabis has ...

from Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

to Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

. Todd Cunningham pleaded guilty to possession and conspiracy to sell marijuana. At his son's sentencing hearing, Cunningham fought back tears as he begged the judge for leniency (Todd was sentenced to two and a half years in prison, in part because he tested positive for cocaine

Cocaine is a tropane alkaloid and central nervous system stimulant, derived primarily from the leaves of two South American coca plants, ''Erythroxylum coca'' and ''Erythroxylum novogranatense, E. novogranatense'', which are cultivated a ...

three times while on bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Court bail may be offered to secure the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when ...

). After the sentencing, Cunningham was seen leaving the courthouse crying. Cunningham's press secretary

A press secretary or press officer is a senior advisor who provides advice on how to deal with the news media and, using news management techniques, helps their employer to maintain a positive public image and avoid negative media coverage.

Dutie ...

responded to accusations of double standards

A double standard is the application of different sets of principles for situations that are, in principle, the same. It is often used to describe treatment whereby one group is given more latitude than another. A double standard arises when two ...

with: "The sentence Todd got had nothing to do with who Duke is. Duke has always been tough on drugs and remains tough on drugs."

Legislative achievements

Cunningham was the lead sponsor of the Shark Finning Prohibition Act, which banned the practice ofshark finning

Shark finning is the act of removing fins from sharks and discarding the rest of the shark back into the ocean. This act is prohibited in many countries. The sharks are often still alive when discarded, but without their fins.Spiegel, J. (200 ...

in all U.S. waters, and pushed America to the lead on efforts to ban shark finning worldwide. For his efforts, Cunningham was named as a "Conservation Hero" by the Audubon Society

The National Audubon Society (Audubon; ) is an American non-profit environmental organization dedicated to conservation of birds and their habitats. Located in the United States and incorporated in 1905, Audubon is one of the oldest of such orga ...

and the Ocean Wildlife Campaign. Cunningham also unsuccessfully advocated for the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

for all those convicted of shark finning

Shark finning is the act of removing fins from sharks and discarding the rest of the shark back into the ocean. This act is prohibited in many countries. The sharks are often still alive when discarded, but without their fins.Spiegel, J. (200 ...

.

Cunningham co-sponsored, along with Democrat John Murtha

John Patrick Murtha Jr. ( ; June 17, 1932 – February 8, 2010) was an Politics of the United States, American politician from the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Murtha, a Democratic Party (United States), Democrat, re ...

, the so-called " Flag Desecration Amendment", which would add the following sentence to the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

:

The Congress shall have power to prohibit the physical desecration of theThe proposed amendment has passed the House many times, but narrowly missed the requisite 2/3 majority vote for passage in the Senate. Cunningham also advocated for theFlag of the United States The national flag of the United States, often referred to as the American flag or the U.S. flag, consists of thirteen horizontal Bar (heraldry), stripes, Variation of the field, alternating red and white, with a blue rectangle in the Canton ( ....

death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

for all those convicted of flag desecration

Flag desecration is the desecration of a flag, violation of flag protocol, or various acts that intentionally destroy, damage, or mutilate a flag in public. In the case of a national flag, such action is often intended to make a political point ...

.

Cunningham was the driving force behind the Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act

The Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act (LEOSA) is a Law of the United States, United States federal law, enacted in 2004, that allows two classes of persons—the "qualified Police officer, law enforcement officer" and the "qualified retired or ...

which was passed and signed into law by President George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

in July 2004. The law grants the authority to non-federal law enforcement

Law enforcement is the activity of some members of the government or other social institutions who act in an organized manner to enforce the law by investigating, deterring, rehabilitating, or punishing people who violate the rules and norms gove ...

officers from any jurisdiction to carry a firearm

A firearm is any type of gun that uses an explosive charge and is designed to be readily carried and operated by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see legal definitions).

The first firearms originate ...

anywhere within the jurisdiction of the United States.

Cunningham supported reinstitution of the Selective Service

The Selective Service System (SSS) is an independent agency of the United States government that maintains a database of registered male U.S. citizens and other U.S. residents potentially subject to military conscription (i.e., the draft).

...

draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

.

Scandals and corruption

Allegations

In June 2005, a story appeared in ''The San Diego Union-Tribune

''The San Diego Union-Tribune'' is a metropolitan daily newspaper published in San Diego, California, that has run since 1868. Its name derives from a 1992 merger between the two major daily newspapers at the time, ''The San Diego Union'' and ...

'' by Marcus Stern and Jerry Kammer, who later received a Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

for their reporting. The story revealed that a defense contractor

A defense contractor is a business organization or individual that provides products or services to a military or intelligence department of a government. Products typically include military or civilian aircraft, ships, vehicles, weaponry, and ...

, Mitchell Wade, founder of the defense contracting firm MZM Inc. (since renamed Athena Innovative Solutions Inc. and later acquired by CACI

CACI International Inc. (originally California Analysis Center, Inc., then Consolidated Analysis Center, Inc.) is an American multinational corporation, multinational professional services and information technology company headquartered in Nor ...

), bought Cunningham's house in Del Mar in 2003 for $1,675,000. A month later, Wade placed it back on the market where it remained unsold for eight months until the price was reduced to $975,000. Cunningham was a member of the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee at the time. Soon after the purchase, Wade's company began to receive tens of millions of dollars worth of defense and intelligence contracts. Cunningham claimed the deal was legitimate, adding, "I feel very confident that I haven't done anything wrong."

Later in June, it was further reported that Cunningham lived rent-free on a yacht

A yacht () is a sail- or marine propulsion, motor-propelled watercraft made for pleasure, cruising, or racing. There is no standard definition, though the term generally applies to vessels with a cabin intended for overnight use. To be termed a ...

named the "Duke Stir" while he was in Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

. The yacht was owned by Wade; Cunningham paid only for maintenance. An article in ''The San Diego Union-Tribune'' reported that Cunningham liked to invite women to his yacht. Two of them said that he would change into pajama bottoms and a turtleneck sweater to entertain them with chilled champagne

Champagne (; ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, which demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, spe ...

by the light of a lava lamp

A lava lamp is a decorative lamp that was invented in 1963 by British entrepreneur Edward Craven Walker, the founder of the lighting company Mathmos.

It consists of a bolus of a special coloured wax mixture inside a glass vessel, the remainde ...

.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

launched an investigation regarding the real estate transaction. Cunningham's home, MZM corporate offices, and Wade's home were all simultaneously raided by several federal agencies with warrants on July 1, 2005.

On July 14, 2005, Cunningham announced he would not run for a ninth term in 2006, saying that while he believed he would be cleared of any wrongdoing, he could not defend himself and run for re-election at the same time. He admitted to displaying "poor judgment" when he sold his house to Wade.

Besides Wade, the three other co-conspirators were: Brent R. Wilkes, founder of San Diego–based ADCS Inc.; New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

businessman Thomas Kontogiannis; and John T. Michael, Kontogiannis' nephew and the owner of a New York–based mortgage company, Coastal Capital Corp. Property records show the company made $1.15 million in real estate loans to Cunningham, two of which were used in the purchase of his Rancho Santa Fe mansion. Court records show that Wade paid off one of those loans.

In 1997, Cunningham had pushed the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense, in Arlington County, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. The building was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As ...

into buying a $20 million document-digitization system created by ADCS Inc., one of several defense companies owned by Wilkes. The Pentagon did not want to buy the system. When it had not done so three years later, Cunningham angrily demanded the firing of Lou Kratz, an assistant undersecretary of defense Cunningham held responsible for the delays. It later emerged that Wilkes reportedly gave Cunningham more than $630,000 in cash and favors.

Cunningham was also criticized for selling merchandise on his personal website, such as a $595 Buck knife featuring the official Congressional seal. He failed to obtain permission to use the seal, which is a federal offense

In the United States, a federal crime or federal offense is an act that is made illegal by U.S. federal legislation enacted by both the United States Senate and United States House of Representatives and signed into law by the president. Prosec ...

.

On April 27, 2006, months after his guilty plea, ''The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' (''WSJ''), also referred to simply as the ''Journal,'' is an American newspaper based in New York City. The newspaper provides extensive coverage of news, especially business and finance. It operates on a subscriptio ...

'' reported that, in addition to all the favors, gifts and money Cunningham received from defense contractors who wanted his help in obtaining contracts, he may have been provided with prostitute

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-pe ...

s, narcotics

The term narcotic (, from ancient Greek ναρκῶ ''narkō'', "I make numb") originally referred medically to any psychoactive compound with numbing or paralyzing properties. In the United States, it has since become associated with opiates ...

, hotel rooms, limousine

A limousine ( or ), or limo () for short, is a large, chauffeur-driven luxury vehicle with a partition between the driver compartment and the passenger compartment which can be operated mechanically by hand or by a button electronically. A luxu ...

s, and other amenities.

Plea agreement

On November 28, 2005, Cunningham pleaded guilty totax evasion

Tax evasion or tax fraud is an illegal attempt to defeat the imposition of taxes by individuals, corporations, trusts, and others. Tax evasion often entails the deliberate misrepresentation of the taxpayer's affairs to the tax authorities to red ...

, conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, ploy, or scheme, is a secret plan or agreement between people (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder, treason, or corruption, especially with a political motivat ...

to commit bribery

Bribery is the corrupt solicitation, payment, or Offer and acceptance, acceptance of a private favor (a bribe) in exchange for official action. The purpose of a bribe is to influence the actions of the recipient, a person in charge of an official ...

, mail fraud

Mail fraud and wire fraud are terms used in the United States to describe the use of a physical (e.g., the U.S. Postal Service) or electronic (e.g., a phone, a telegram, a fax, or the Internet) mail system to defraud another, and are U.S. fede ...

and wire fraud

Mail fraud and wire fraud are terms used in the United States to describe the use of a physical (e.g., the U.S. Postal Service) or electronic (e.g., a phone, a telegram, a fax, or the Internet) mail system to defraud another, and are U.S. fede ...

in federal court in San Diego. The investigation which led to the conviction of Cunningham was led by a team of Marcus Stern, Jerry Kammer and Dean Calbreath. Among the many bribes Cunningham admitted receiving was the sale of his home in Del Mar at an inflated price, the free use of the yacht "Duke Stir," a used Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated in ...

, antique furniture, Persian rugs, jewelry

Jewellery (or jewelry in American English) consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment such as brooches, ring (jewellery), rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the ...

, and a $2,000 contribution for his daughter's college graduation party. Cunningham's attorney, Mark Holscher, later said that the government's evidence was so overwhelming that he had no choice but to recommend a guilty plea

In law, a plea is a defendant's response to a criminal charge. A defendant may plead guilty or not guilty. Depending on jurisdiction, additional pleas may be available, including '' nolo contendere'' (no contest), no case to answer (in the ...

. With the plea bargain A plea bargain, also known as a plea agreement or plea deal, is a legal arrangement in criminal law where the defendant agrees to plead guilty or no contest to a charge in exchange for concessions from the prosecutor. These concessions can include a ...

, Cunningham faced a maximum of 10 years; had he fought the charges, Cunningham risked spending the rest of his life in prison.

As part of his guilty plea, Cunningham agreed to forfeit his $2.55 million home in Rancho Santa Fe, which he bought with the proceeds of the sale of the Del Mar house. Cunningham initially tried to sell the Rancho Santa Fe house, but federal prosecutors moved to block the sale after finding evidence it was purchased with Wade's money. (Wade, with others, even paid off the balance Cunningham owed on the mortgage.) Cunningham also forfeited more than $1.8 million in cash, antiques, rugs, and other items.

Also as part of the plea agreement, Cunningham agreed to help the government in its prosecution of others involved in the defense contractor bribery scandal.

Resignation

Cunningham announced that he would resign from the House at apress conference

A press conference, also called news conference or press briefing, is a media event in which notable individuals or organizations invite journalism, journalists to hear them speak and ask questions. Press conferences are often held by politicia ...

just after entering his plea. He read a prepared statement announcing that he was stepping down:

When I announced several months ago that I would not seek re-election, I publicly declared my innocence because I was not strong enough to face the truth. So, I misled my family, staff, friends, colleagues, the public—even myself. For all of this, I am deeply sorry. The truth is—I broke the law, concealed my conduct, and disgraced my high office. I know that I will forfeit my freedom, my reputation, my worldly possessions, and most importantly, the trust of my friends and family... In my life, I have known great joy and great sorrow. And now I know great shame. I learned in Vietnam that the true measure of a man is how he responds to adversity. I cannot undo what I have done. But I can atone. I am now almost 65 years old and, as I enter the twilight of my life, I intend to use the remaining time that God grants me to make amends.Cunningham submitted his official resignation letter to the Clerk of the House and to Californian Governor

Arnold Schwarzenegger

Arnold Alois Schwarzenegger (born July30, 1947) is an Austrian and American actor, businessman, former politician, and former professional bodybuilder, known for his roles in high-profile action films. Governorship of Arnold Schwarzenegger, ...

on December 6, 2005.

Sentencing and prison

On March 3, 2006, U.S. District Judge Larry A. Burns sentenced Cunningham to eight years and four months in prison. Federal prosecutors pushed for the maximum sentence of ten years, but Cunningham's defense lawyers argued that at 64 years old and with

On March 3, 2006, U.S. District Judge Larry A. Burns sentenced Cunningham to eight years and four months in prison. Federal prosecutors pushed for the maximum sentence of ten years, but Cunningham's defense lawyers argued that at 64 years old and with prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is the neoplasm, uncontrolled growth of cells in the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system below the bladder. Abnormal growth of the prostate tissue is usually detected through Screening (medicine), screening tests, ...

, Cunningham would likely die in prison if he received the full sentence. Burns cited his military service in Vietnam, age and health as the reason the full ten years was not imposed. Prosecutors announced that they were satisfied with the sentence, which was the longest jail term ever given to a former Congressman.

On the day of sentencing, Cunningham was lighter than when allegations first surfaced 9 months earlier. After receiving his sentence, Cunningham made a request to see his 91-year-old mother one last time before going to prison. "I made a very wrong turn. I rationalized decisions I knew were wrong. I did that, sir," Cunningham said. The request was denied, and Burns remanded him immediately upon rendering the sentence. Cunningham was incarcerated in the minimum security

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol, penitentiary, detention center, correction center, correctional facility, or remand center, is a facility where people are imprisoned under the authority of the state, usually as punishment for various crim ...

satellite camp at the U.S. Penitentiary at Tucson, Arizona, with a scheduled release date of June 4, 2013. He spent his time at the prison teaching fellow inmates to obtain their GED

Ged or GED may refer to:

Places

* Ged, Louisiana, an unincorporated community in the United States

* Ged, a village in Bichiwara Tehsil, Dungarpur District, Rajasthan, India

* Delaware Coastal Airport, in Delaware, US, callsign GED

People

* Ged B ...

, as well as advocating for prison reform.

Despite his guilty plea, Cunningham received pension

A pension (; ) is a fund into which amounts are paid regularly during an individual's working career, and from which periodic payments are made to support the person's retirement from work. A pension may be either a " defined benefit plan", wh ...

s for his 21 years of U.S. Navy service and almost 15 years in Congress. However, prosecutors were successful in garnishing them for back taxes

Back taxes is a term for taxes that were not completely paid when due. Typically, these are taxes that are owed from a previous year. Causes for back taxes include failure to pay taxes by the deadline, failure to correctly report one's income, or ...

and penalties. In June 2010, Cunningham submitted a handwritten three-page letter to Burns, complaining that the IRS

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting Taxation in the United States, U.S. federal taxes and administerin ...

was "killing" him by seizing all his remaining savings and his Congressional and Navy pensions, penalties he felt were not warranted under his plea agreement. Burns wrote back in August 2010, stating that the agency was collecting back taxes, interest and penalties on the bribes Cunningham received in 2003 and 2004; thus, there was no action for Burns to take.

In April 2011, Cunningham sent a ten-page typewritten document pleading his case to ''USA Today

''USA Today'' (often stylized in all caps) is an American daily middle-market newspaper and news broadcasting company. Founded by Al Neuharth in 1980 and launched on September 14, 1982, the newspaper operates from Gannett's corporate headq ...

'', the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' is an American Newspaper#Daily, daily newspaper that began publishing in Los Angeles, California, in 1881. Based in the Greater Los Angeles city of El Segundo, California, El Segundo since 2018, it is the List of new ...

'', ''Talking Points Memo

''Talking Points Memo'' (''TPM'') is a liberal political news and opinion blog created and run by Josh Marshall that debuted on November 12, 2000. The name is a tongue-in-cheek reference to a "talking points memo" that was often discussed duri ...

'' and '' San Diego CityBeat''. He titled the document "The Untold Story of Duke Cunningham". In the document, Cunningham wrote that because Burns had declared his case closed, he was now offering to speak to the media, which had "inundated" him with inquiries since 2004. According to ''CityBeat'', in the statement, Cunningham claimed that he was "doped up on sedatives" and made his plea knowing that it was "90 to 95% untrue".

Release from prison

Cunningham was released to ahalfway house

A halfway house is a type of prison or institute intended to teach (or reteach) the necessary skills for people to re-integrate into society and better support and care for themselves. Halfway houses are typically either state sponsored for those ...

in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

in February 2013. On June 4, 2013, he was completely released from confinement.

Cunningham told a federal judge that he planned to live in Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

and that he would live on $1,700 a month. In his letter, Cunningham pleaded for a gun permit, saying he longed to hunt in Arkansas. The judge denied the request as being beyond the scope of his authority, citing the law that limits gun permits for convicted criminals: a law that Cunningham voted for while in Congress. Cunningham received a pardon from President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

on January 13, 2021, conditioned on his payment of penalties of restitution and forfeiture totaling $3,655,539.50.

Reactions to the scandal

Darrell Issa

Darrell Edward Issa ( ; born November 1, 1953) is an American businessman and politician serving as the U.S. representative for California's 48th congressional district. He represented the 50th congressional district from 2021 to 2023. A memb ...

, a Republican who represented the neighboring 49th district, said after Cunningham's plea that he had been waiting for Cunningham to explain his behavior "in a way that made sense to us" and that Cunningham's behavior "fell below the standard the public demands of its elected representatives".

Francine Busby, Cunningham's Democratic challenger in 2004 and the Democratic candidate for the 50th district in the runoff election to fill Cunningham's vacancy, called November 28 "a sad day for the people" and called for support for her proposed ethics reform bill, the "Clean House Act", saying that "our government in Washington is broken."

In an editorial on November 29, ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'' called the Cunningham affair "the most brazen bribery conspiracy in modern congressional history". Later that day, President George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

called Cunningham's actions "outrageous" at a press briefing in El Paso, Texas

El Paso (; ; or ) is a city in and the county seat of El Paso County, Texas, United States. The 2020 United States census, 2020 population of the city from the United States Census Bureau, U.S. Census Bureau was 678,815, making it the List of ...

. He also said that Cunningham should "pay a serious price" for his crimes. House Speaker Dennis Hastert

John Dennis Hastert ( ; born January 2, 1942) is an American former politician, teacher, and wrestling coach who represented from 1987 to 2007 and served as the 51st speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1999 to 2007. Hast ...

said in a December 6 statement that Cunningham was a "war hero"; but that he broke "the public trust he has built through his military and congressional career".

On February 9, 2006, Senator John Kerry

John Forbes Kerry (born December 11, 1943) is an American attorney, politician, and diplomat who served as the 68th United States secretary of state from 2013 to 2017 in the Presidency of Barack Obama#Administration, administration of Barac ...

introduced a bill, the "Federal Pension Forfeiture Act" (nicknamed the "Duke Cunningham Act"), to prevent lawmakers who have been convicted of official misconduct from collecting taxpayer-funded pensions. The bill died in committee, by unanimous vote.

Aftermath

* Almost as soon as Cunningham pleaded guilty, Intelligence Committee chairmanPete Hoekstra

Cornelis Piet Hoekstra (; born October 30, 1953) is a Dutch-American politician who is serving as Ambassador to Canada. Hoekstra had served as the United States Ambassador to the Netherlands from January 10, 2018, to January 17, 2021. A member ...

of Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

announced his panel would investigate whether Cunningham used his post on that committee to steer contracts to favored companies. Hoekstra said that Cunningham "no longer gets the benefit of the doubt" due to his admission to "very, very serious" crimes.

* On January 6, 2006, ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' reported that Cunningham cooperated with law enforcement by wearing a concealed recording device (a "wire") while meeting with associates prior to his guilty plea. It is not known whom he met with while wired, but there was speculation Cunningham's misdeeds were not isolated instances and his case would reveal a larger web of corruption.

* In February 2006, Mitchell Wade pleaded guilty to paying Cunningham more than $1 million in bribes in exchange for millions more in government contracts.

* In March 2006, it was revealed that CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

officials opened an investigation into the CIA's No. 3 official, Kyle Foggo, and his relationship with Wilkes, "one of his closest friends", according to the article. Foggo said that all of the contracts he oversaw were properly awarded and administered. On May 12, FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

officials raided the Vienna, Virginia

Vienna () is a town in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census, Vienna has a population of 16,473. Significantly more people live in ZIP codes with the Vienna postal addresses (22180, 22181, ...

, home of Foggo in connection with the scandal. In February 2007, Foggo was charged with fraud and other offenses in the Cunningham corruption investigation. The indictment also named Wilkes and John T. Michael.

* In November 2010, Wilkes' lawyers filed documents in court in a bid to gain a re-trial that included statements from Cunningham saying "Wilkes never bribed me." Cunningham is quoted as saying any meals, trips or gifts from Wilkes to him were merely gifts between long-time friends, not bribes. Cunningham also stated that he had been coached by prosecutors to avoid responding to questions where his version of the facts differed from the prosecutors' theory. Cunningham also denied having made statements attributed to him by federal agents and prosecutors. Notably he denied having sex with any prostitute

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-pe ...

on a trip to Hawaii and explained that at the time he was impotent due to treatment for prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is the neoplasm, uncontrolled growth of cells in the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system below the bladder. Abnormal growth of the prostate tissue is usually detected through Screening (medicine), screening tests, ...

.

* A special election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, or a bypoll in India, is an election used to fill an office that has become vacant between general elections.

A vacancy may arise as a result of an incumben ...

to fill the vacancy left by Cunningham took place on April 11, 2006, between Democrat Francine Busby and Republican Brian Bilbray

Brian Phillip Bilbray (born January 28, 1951) is an American politician who served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1995 to 2001 and again from 2006 to 2013. He is a member of the Republican Party.

Bilbray was Chairman of the House I ...

. No candidate obtained the majority necessary to win outright, so a runoff election was held. Bilbray won the runoff, narrowly defeating Busby. Bilbray beat Busby again in the regular election in November and retained his seat in the House until losing to Democrat Scott Peters in 2012.

* On April 17, the staffs of ''The San Diego Union-Tribune

''The San Diego Union-Tribune'' is a metropolitan daily newspaper published in San Diego, California, that has run since 1868. Its name derives from a 1992 merger between the two major daily newspapers at the time, ''The San Diego Union'' and ...

'' and Copley News Service were awarded the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting

This Pulitzer Prize has been awarded since 1942 for a distinguished example of reporting on national affairs in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily ...

for their investigative work in uncovering Cunningham's crimes.

* Four reporters from the ''Union-Tribune'' and its parent Copley News Service

Copley Press was a privately held newspaper business, founded in Illinois but later based in La Jolla, California. Its flagship paper was ''The San Diego Union-Tribune''.

History

Founder Ira Clifton Copley launched Copley Press c. 1905, eventu ...

, who had written the stories that launched the Cunningham investigation, published a book called ''The Wrong Stuff: The extraordinary saga of Randy "Duke" Cunningham, the most corrupt congressman ever caught''.

Personal life

Cunningham married Susan Albrecht in 1965; they had met in college. They adopted a son together. His wife filed fordivorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganising of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the M ...

and a restraining order

A restraining order or protective order is an order used by a court to protect a person in a situation often involving alleged domestic violence, child abuse and neglect, assault, harassment, stalking, or sexual assault.

Restraining and perso ...

in January 1973, based on her claims of emotional abuse

Emotions are physical and mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure. There is no scientific consensus on a definit ...

, and the divorce was granted eight months later. Cunningham later said that his life hit "rock-bottom" in that year.

In 1973, he met Dan McKinnon, a publisher and son of former Congressman Clinton D. McKinnon, who encouraged him to turn his life around. Cunningham married his second wife, Nancy Jones, in 1974. They had two daughters and separated in July 2005.

See also

*List of American federal politicians convicted of crimes

This list consists of American politicians convicted of crimes either committed or prosecuted while holding office in the Federal government of the United States, federal government. It includes politicians who were convicted or pleaded guilty ...

*List of federal political scandals in the United States

This article provides a list of political scandals that involve officials from the government of the United States, sorted from oldest to most recent.

Scope and organization of political scandals

This article is organized by presidential terms ...

References

External links

*The San Diego Union-Tribune's coverage of the Cunningham scandal

Washington Post Express interview with the authors of "The Wrong Stuff" about Cunningham and Washington's culture of corruption

PAC donors, Indiv donors, Personal Financial Disclosures, Campaign Disbursements, at PoliticalMoneyLine

* * *

Profile

at

SourceWatch

The Center for Media and Democracy (CMD) is a progressive nonprofit watchdog and advocacy organization based in Madison, Wisconsin. CMD publishes ExposedbyCMD.org, SourceWatch.org, and ALECexposed.org.

History

CMD was founded in 1993 by prog ...

*

Documents

Prosecutor's allegations against Cunningham

* *

Cunningham's Sentencing Memorandum

February 17, 2006) , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Cunningham, Duke 1941 births American members of the Churches of Christ American politicians convicted of federal public corruption crimes American Vietnam War flying aces American people convicted of tax crimes Aviators from California California politicians convicted of crimes Living people Military personnel from California National University (California) alumni People from Shelby County, Missouri Politicians convicted of mail and wire fraud Politicians from Los Angeles Politicians from San Diego People pardoned by Donald Trump Recipients of the Air Medal Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) Recipients of the Silver Star Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from California United States Naval Aviators United States Navy officers University of Missouri alumni 21st-century members of the United States House of Representatives