Dryopithecus fontani on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Dryopithecus'' is a

The first ''Dryopithecus'' fossils were described from the French

The first ''Dryopithecus'' fossils were described from the French  Currently, there is only one uncontested species, ''D. fontani''. Specimens are:

* Holotype MNHNP AC 36, three pieces of a male mandible with teeth from Saint-Gaudens in the French Pyrenees. Based on dental development in chimpanzees, it was 6 to 8 years old, and several diagnostic characteristics made from the holotype would be lost in mature ''D. fontani''; A partial left

Currently, there is only one uncontested species, ''D. fontani''. Specimens are:

* Holotype MNHNP AC 36, three pieces of a male mandible with teeth from Saint-Gaudens in the French Pyrenees. Based on dental development in chimpanzees, it was 6 to 8 years old, and several diagnostic characteristics made from the holotype would be lost in mature ''D. fontani''; A partial left

Based on measurements of the

Based on measurements of the

''Dryopithecus'' likely predominantly ate fruit ( frugivory), and evidence of cavities on the teeth of the Austrian ''Dryopithecus'' indicates a high-sugar diet, likely deriving from ripe fruits and honey. Dental wearing indicates ''Dryopithecus'' ate both soft and hard food, which could either indicate they consumed a wide array of different foods, or they ate harder foods as a fallback. Nonetheless, its unspecialized teeth indicate it had a flexible diet, and large body size would have permitted a large gut to aid in the processing of less-digestible food, perhaps stretching to include foods such as leaves ( folivory) in times of famine like in modern apes. Unlike modern apes, ''Dryopithecus'' likely had a high

''Dryopithecus'' likely predominantly ate fruit ( frugivory), and evidence of cavities on the teeth of the Austrian ''Dryopithecus'' indicates a high-sugar diet, likely deriving from ripe fruits and honey. Dental wearing indicates ''Dryopithecus'' ate both soft and hard food, which could either indicate they consumed a wide array of different foods, or they ate harder foods as a fallback. Nonetheless, its unspecialized teeth indicate it had a flexible diet, and large body size would have permitted a large gut to aid in the processing of less-digestible food, perhaps stretching to include foods such as leaves ( folivory) in times of famine like in modern apes. Unlike modern apes, ''Dryopithecus'' likely had a high

The remains of ''Dryopithecus'' are often associated with several large mammals, such as elephants (e. g., though not limited to, '' Gomphotherium''), rhinos (e. g., '' Lartetotherium''), pigs (e. g., ''

The remains of ''Dryopithecus'' are often associated with several large mammals, such as elephants (e. g., though not limited to, '' Gomphotherium''), rhinos (e. g., '' Lartetotherium''), pigs (e. g., ''

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial n ...

of extinct great ape

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the e ...

s from the middle

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek (d ...

–late Miocene

The Late Miocene (also known as Upper Miocene) is a sub-epoch of the Miocene Epoch made up of two stages. The Tortonian and Messinian stages comprise the Late Miocene sub-epoch, which lasted from 11.63 Ma (million years ago) to 5.333 Ma.

The ...

boundary of Europe 12.5 to 11.1 million years ago

The abbreviation Myr, "million years", is a unit of a quantity of (i.e. ) years, or 31.556926 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr (million years) is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used with Mya (million years ago). ...

(mya). Since its discovery in 1856, the genus has been subject to taxonomic turmoil, with numerous new species being described from single remains based on minute differences amongst each other, and the fragmentary nature of the holotype specimen makes differentiating remains difficult. There is currently only one uncontested species, the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen( ...

''D. fontani'', though there may be more. The genus is placed into the tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to confl ...

Dryopithecini, which is either an offshoot of orangutan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the gen ...

s, African apes

Homininae (), also called "African hominids" or "African apes", is a subfamily of Hominidae. It includes two tribes, with their extant as well as extinct species: 1) the tribe Hominini (with the genus ''Homo'' including modern humans and numerou ...

, or is its own separate branch.

A male specimen was estimated to have weighed in life. ''Dryopithecus'' likely predominantly ate ripe fruit from trees, suggesting a degree of suspensory behaviour to reach them, though the anatomy of a humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a roun ...

and femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates wit ...

suggest a greater reliance on walking on all fours (quadrupedalism

Quadrupedalism is a form of locomotion where four limbs are used to bear weight and move around. An animal or machine that usually maintains a four-legged posture and moves using all four limbs is said to be a quadruped (from Latin ''quattuo ...

). The face was similar to gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four ...

s, and males had longer canines than females, which is typically correlated with high levels of aggression

Aggression is overt or covert, often harmful, social interaction with the intention of inflicting damage or other harm upon another individual; although it can be channeled into creative and practical outlets for some. It may occur either reacti ...

. They lived in a seasonal, paratropical climate, and may have built up fat reserves for winter. European great apes likely went extinct during a drying and cooling trend in the Late Miocene which caused the retreat of warm-climate forests.

Etymology

Thegenus name

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

''Dryopithecus'' comes from Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

''drus'' "oak tree" and ''pithekos'' " ape" because the authority believed it inhabited an oak or pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family (biology), family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanic ...

forest in an environment similar to modern day Europe. The species ''D. fontani'' was named in honour of its discoverer, local collector Monsieur Alfred Fontan.

Taxonomy

The first ''Dryopithecus'' fossils were described from the French

The first ''Dryopithecus'' fossils were described from the French Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

by French paleontologist Édouard Lartet in 1856, three years before Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

published his ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

''. Subsequent authors noted similarities to modern African great ape

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the e ...

s. In his ''The Descent of Man

''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, a form of b ...

'', Darwin briefly noted that ''Dryopithecus'' casts doubt on the African origin of apes:

''Dryopithecus'' taxonomy has been the subject of much turmoil, with new specimens being the basis of a new species or genus based on minute differences, resulting in several now-defunct species. By the 1960s, all non-human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

apes were classified into the now- obsolete family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

Pongidae, and extinct apes into Dryopithecidae. In 1965, English palaeoanthropologist David Pilbeam and American palaeontologist Elwyn L. Simons

Elwyn LaVerne Simons (July 14, 1930 – March 6, 2016) was an American paleontologist, paleozoologist, and a wildlife conservationist for primates. He was known as the father of modern primate paleontology for his discovery of some of humankind ...

separated the genus–which included specimens from across the Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by th ...

at the time–into three subgenera

In biology, a subgenus (plural: subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed betwee ...

: ''Dryopithecus'' in Europe, ''Sivapithecus'' in Asia, and ''Proconsul'' in Africa. Afterwards, there was discussion over whether each of these subgenera should be elevated to genus. In 1979, '' Sivapithecus'' was elevated to genus, and ''Dryopithecus'' was subdivided again into the subgenera ''Dryopithecus'' in Europe, and ''Proconsul'', ''Limnopithecus'', and ''Rangwapithecus'' in Africa. Since that time, several more species were assigned and moved, and by the 21st century, the genus included ''D. fontani'', '' D. brancoi'', '' D. laietanus'', and '' D. crusafonti''. However, the 2009 discovery of a partial skull of ''D. fontani'' caused many of them to be split off into different genera, such as the newly erected '' Hispanopithecus'', because part of the confusion was caused by the fragmentary nature of the ''Dryopithecus'' holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of seve ...

with vague and incomplete diagnostic characteristics.

Currently, there is only one uncontested species, ''D. fontani''. Specimens are:

* Holotype MNHNP AC 36, three pieces of a male mandible with teeth from Saint-Gaudens in the French Pyrenees. Based on dental development in chimpanzees, it was 6 to 8 years old, and several diagnostic characteristics made from the holotype would be lost in mature ''D. fontani''; A partial left

Currently, there is only one uncontested species, ''D. fontani''. Specimens are:

* Holotype MNHNP AC 36, three pieces of a male mandible with teeth from Saint-Gaudens in the French Pyrenees. Based on dental development in chimpanzees, it was 6 to 8 years old, and several diagnostic characteristics made from the holotype would be lost in mature ''D. fontani''; A partial left humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a roun ...

arm bone, an additional mandible (MNHNP 1872-2), a left lower jaw and five isolated teeth are also known from the site.

*An upper incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, w ...

, NMB G.a.9., and female upper molar, FSL 213981, come from Saint-Alban-de-Roche

Saint-Alban-de-Roche () is a commune in the Isère department in southeastern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Isère department

The following is a list of the 512 Communes of France, communes in the French Departments of France ...

, France.

*A male partial face, IPS35026, and femur, IPS41724, from Vallès Penedès in Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

, Spain.

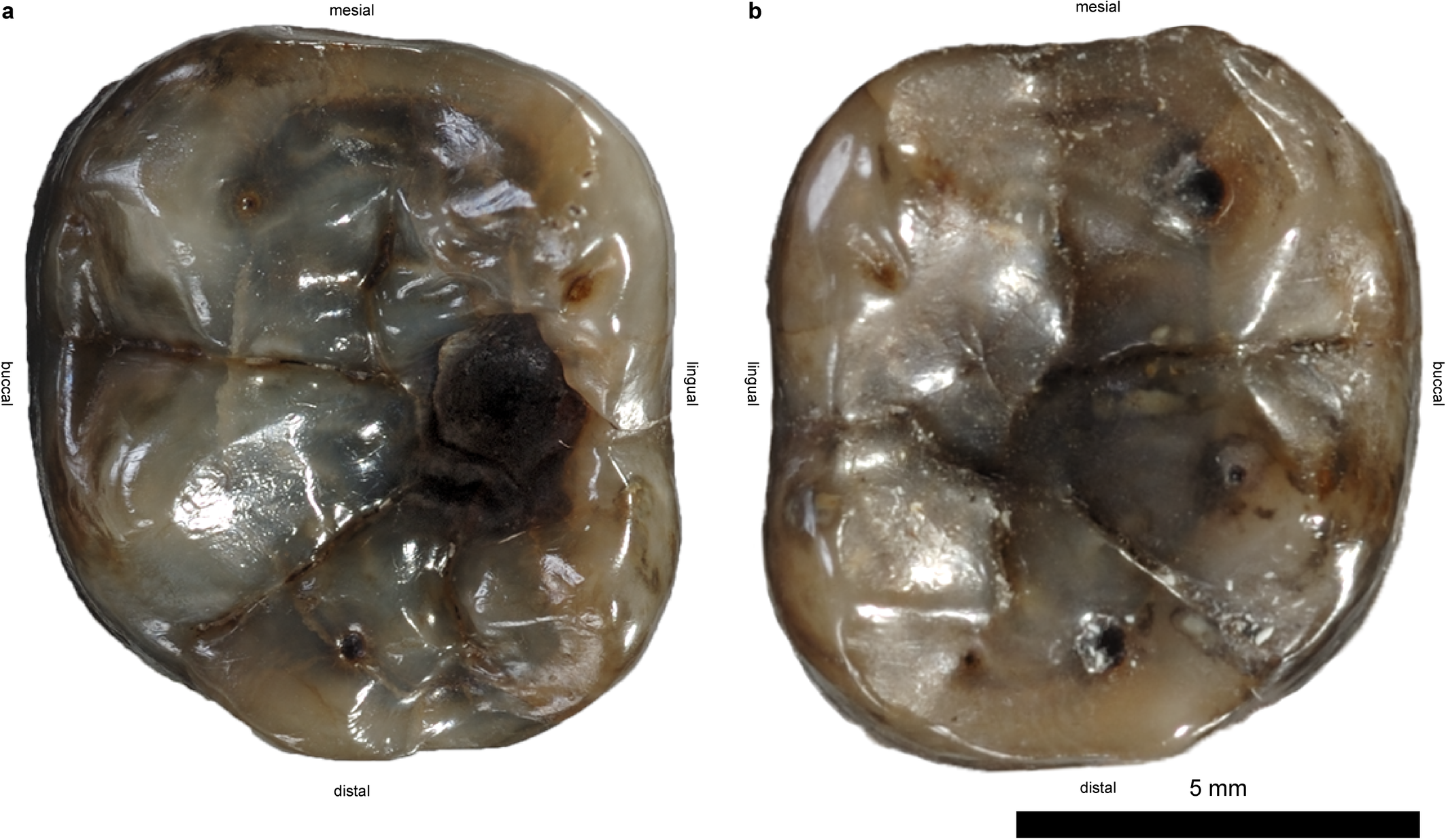

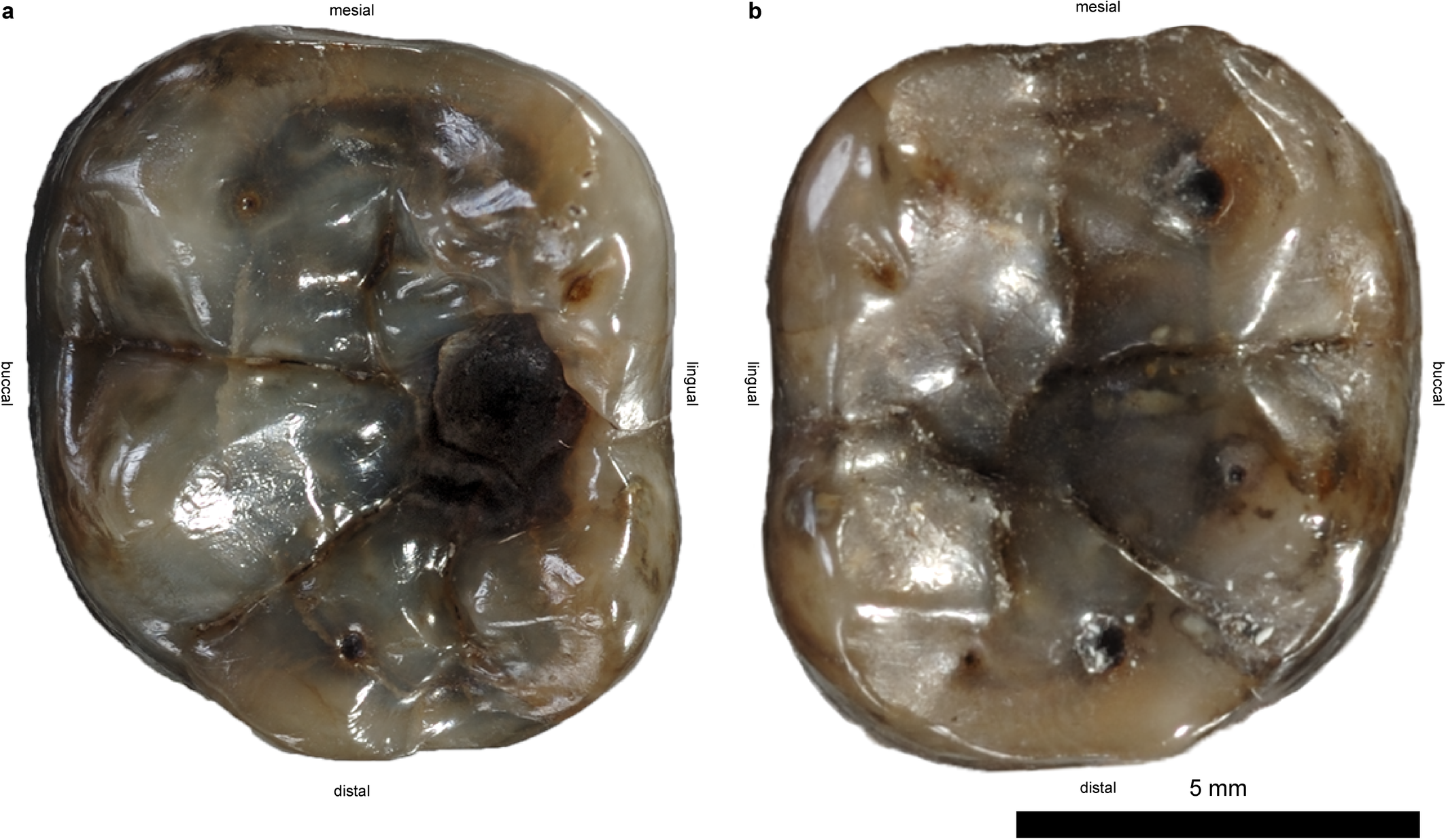

*A female mandible with teeth, LMK-Pal 5508, from St. Stefan, Carinthia, Austria 12.5 mya, which could possibly be considered a separate species, "''D. carinthiacus''".

''Dryopithecus'' is classified into the namesake great ape tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to confl ...

Dryopithecini, along with '' Hispanopithecus'', '' Rudapithecus'', ''Ouranopithecus

''Ouranopithecus'' ("celestial ape" from Ancient Greek

οὐρανός (ouranós), "sky, heaven" + πίθηκος (píthēkos),"ape") is a genus of extinct Eurasian great ape represented by two species, ''Ouranopithecus macedoniensis'', a late M ...

'', '' Anoiapithecus'', and '' Pierolapithecus'', though the latter two may belong to ''Dryopithecus'', the former two may be synonymous, and the former three can also be placed into their own tribes. Dryopithecini is either regarded as an offshoot of orangutan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the gen ...

s ( Ponginae), an ancestor to African apes and humans (Homininae

Homininae (), also called "African hominids" or "African apes", is a subfamily of Hominidae. It includes two tribes, with their extant as well as extinct species: 1) the tribe Hominini (with the genus ''Homo'' including modern humans and numer ...

), or its own separate branch (Dryopithecinae

Dryopithecini is an extinct tribe of Eurasian and African great apes that are believed to be close to the ancestry of gorillas, chimpanzees and humans. Members of this tribe are known as dryopithecines.

Taxonomy

* Tribe Dryopithecini †

** '' ...

).

''Dryopithecus'' was a part of an adaptive radiation

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic int ...

of great ape

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the e ...

s in the expanding forests of Europe in the warm climates of the Miocene Climatic Optimum, possibly descending from early

Early may refer to:

History

* The beginning or oldest part of a defined historical period, as opposed to middle or late periods, e.g.:

** Early Christianity

** Early modern Europe

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa

* Early, Texas

* Early ...

or middle

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek (d ...

Miocene African apes which diversified in the proceeding Middle Miocene disruption

The term Middle Miocene disruption, alternatively the Middle Miocene extinction or Middle Miocene extinction peak, refers to a wave of extinctions of terrestrial and aquatic life forms that occurred around the middle of the Miocene, roughly 14 m ...

(a cooling event). It is possible great apes first evolved in Europe or Asia, and then migrated down into Africa.

Description

Based on measurements of the

Based on measurements of the femoral head

The femoral head (femur head or head of the femur) is the highest part of the thigh bone ( femur). It is supported by the femoral neck.

Structure

The head is globular and forms rather more than a hemisphere, is directed upward, medialward, and a ...

of the Spanish IPS41724, the living weight for a male ''Dryopithecus'' was estimated to be .

''Dryopithecus'' teeth are most similar to those of modern chimps. The teeth are small and have a thin enamel layer. ''Dryopithecus'' has a slender jaw, indicating it was not well-suited for eating abrasive or hard food. Like modern apes, the males have pronounced canine teeth. The molars are wide, and the premolars wider. It has a wide roof of the mouth

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. The nasal septum divide ...

, a long muzzle (prognathism

Prognathism, also called Habsburg jaw or Habsburgs' jaw primarily in the context of its prevalence amongst members of the House of Habsburg, is a positional relationship of the mandible or maxilla to the skeletal base where either of the jaws pr ...

), and a large nose which is oriented nearly vertically to the face. In total, the face shows many similarities to the gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four ...

; since early to middle Miocene African apes do not share such similarities, gorilla-like features likely evolved independently in ''Dryopithecus'' rather than as a result of close affinities

In post-classical history, an affinity was a collective name for the group ( retinue) of (usually) men whom a lord gathered around himself in his service; it has been described by one modern historian as "the servants, retainers, and other foll ...

.

The humerus, measuring an approximate , is similar in size and form to the bonobo

The bonobo (; ''Pan paniscus''), also historically called the pygmy chimpanzee and less often the dwarf chimpanzee or gracile chimpanzee, is an endangered great ape and one of the two species making up the genus '' Pan,'' the other being the co ...

. Like in bonobos, the shaft

Shaft may refer to:

Rotating machine elements

* Shaft (mechanical engineering), a rotating machine element used to transmit power

* Line shaft, a power transmission system

* Drive shaft, a shaft for transferring torque

* Axle, a shaft around whi ...

bows outward, and the insertion

Insertion may refer to:

*Insertion (anatomy), the point of a tendon or ligament onto the skeleton or other part of the body

*Insertion (genetics), the addition of DNA into a genetic sequence

*Insertion, several meanings in medicine, see ICD-10-PCS

...

for the triceps and deltoids

The deltoid muscle is the muscle forming the rounded contour of the human shoulder. It is also known as the 'common shoulder muscle', particularly in other animals such as the domestic cat. Anatomically, the deltoid muscle appears to be made up o ...

was poorly developed, suggesting ''Dryopithecus'' was not as adept to suspensory behaviour as orangutans. The femoral neck

The femoral neck (femur neck or neck of the femur) is a flattened pyramidal process of bone, connecting the femoral head with the femoral shaft, and forming with the latter a wide angle opening medialward.

Structure

The neck is flattened from ...

, which connects the femoral head to the femoral shaft

The body of femur (or shaft of femur) is the almost cylindrical, long part of the femur. It is a little broader above than in the center, broadest and somewhat flattened from before backward below. It is slightly arched, so as to be convex in front ...

, is not very long nor steep; the femoral head is positioned low to the greater trochanter; and the lesser trochanter is positioned more towards the backside. All these characteristics are important in the mobility of the hip joint, and indicate a quadrupedal mode of locomotion rather than suspensory. However, fruit trees in the time and area of the Austrian ''Dryopithecus'' were typically high and bore fruit on thinner terminal branches, suggesting suspensory behaviour to reach them.

Paleobiology

''Dryopithecus'' likely predominantly ate fruit ( frugivory), and evidence of cavities on the teeth of the Austrian ''Dryopithecus'' indicates a high-sugar diet, likely deriving from ripe fruits and honey. Dental wearing indicates ''Dryopithecus'' ate both soft and hard food, which could either indicate they consumed a wide array of different foods, or they ate harder foods as a fallback. Nonetheless, its unspecialized teeth indicate it had a flexible diet, and large body size would have permitted a large gut to aid in the processing of less-digestible food, perhaps stretching to include foods such as leaves ( folivory) in times of famine like in modern apes. Unlike modern apes, ''Dryopithecus'' likely had a high

''Dryopithecus'' likely predominantly ate fruit ( frugivory), and evidence of cavities on the teeth of the Austrian ''Dryopithecus'' indicates a high-sugar diet, likely deriving from ripe fruits and honey. Dental wearing indicates ''Dryopithecus'' ate both soft and hard food, which could either indicate they consumed a wide array of different foods, or they ate harder foods as a fallback. Nonetheless, its unspecialized teeth indicate it had a flexible diet, and large body size would have permitted a large gut to aid in the processing of less-digestible food, perhaps stretching to include foods such as leaves ( folivory) in times of famine like in modern apes. Unlike modern apes, ''Dryopithecus'' likely had a high carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may or ...

, low fibre

Fiber or fibre (from la, fibra, links=no) is a natural or artificial substance that is significantly longer than it is wide. Fibers are often used in the manufacture of other materials. The strongest engineering materials often incorpora ...

diet.

A high-fructose

Fructose, or fruit sugar, is a ketonic simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and galactose, that are absorb ...

diet is associated with elevated levels of uric acid

Uric acid is a heterocyclic compound of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen with the formula C5H4N4O3. It forms ions and salts known as urates and acid urates, such as ammonium acid urate. Uric acid is a product of the metabolic breakdown ...

, which is neutralized by uricase

The enzyme urate oxidase (UO), uricase or factor-independent urate hydroxylase, absent in humans, catalyzes the oxidation of uric acid to 5-hydroxyisourate:

:Uric acid + O2 + H2O → 5-hydroxyisourate + H2O2

:5-hydroxyisourate + H2O → alla ...

in most animals except great apes. It is thought they stopped producing it by 15 mya, resulting in increased blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term "blood pressur ...

, which in turn led to increased activity, and a greater ability to build up fat reserves. The palaeoenvironment of late Miocene Austria indicates an abundance of fruiting trees and honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of plants (primar ...

for nine or ten months out of the year, and ''Dryopithecus'' may have relied on these fat reserves during the late winter. High uric acid levels in the blood are also associated with increased intelligence.

''Dryopithecus'' males had larger canines than females, which is associated with high levels of aggression in modern primates.

Paleoecology

The remains of ''Dryopithecus'' are often associated with several large mammals, such as elephants (e. g., though not limited to, '' Gomphotherium''), rhinos (e. g., '' Lartetotherium''), pigs (e. g., ''

The remains of ''Dryopithecus'' are often associated with several large mammals, such as elephants (e. g., though not limited to, '' Gomphotherium''), rhinos (e. g., '' Lartetotherium''), pigs (e. g., ''Listriodon

''Listriodon'' is an extinct genus of pig-like animals that lived in Eurasia during the Miocene.

Description

''Listriodon'' species were generally small in size. In morphology, they show many similarities with peccaries rather than modern pigs. ...

''), antelope (e. g., '' Miotragocerus''), horses (e. g., '' Hippotherium''), hyaenas (e. g., ''Protictitherium

''Protictitherium'' ( gr. first striking beast) is an extinct genus of hyaena that lived across Europe and Asia during the Middle and Late Miocene, it is often considered to be the first hyaena since it contains some of the oldest fossils of ...

''), and big cats (e. g., '' Pseudaelurus''). Other associated primates are the great apes ''Hispanopithecus'', ''Anoiapithecus'', and ''Pierolapithecus''; and the monkey '' Pliopithecus''. These fauna are consistent with a warm, forested, paratropical wetland environment, and it may have lived in a seasonal climate. For the Austrian ''Dryopithecus'', plants such as ''Prunus

''Prunus'' is a genus of trees and shrubs, which includes (among many others) the fruits plums, cherries, peaches, nectarines, apricots, and almonds.

Native to the North American temperate regions, the neotropics of South America, and the p ...

'', grapevine

''Vitis'' (grapevine) is a genus of 79 accepted species of vining plants in the flowering plant family Vitaceae. The genus is made up of species predominantly from the Northern Hemisphere. It is economically important as the source of grapes, b ...

s, black mulberry

''Morus nigra'', called black mulberry or blackberry (not to be confused with the blackberries that are various species of ''Rubus''), is a species of flowering plant in the family Moraceae that is native to southwestern Asia and the Iberian Pen ...

, strawberry trees, hickory

Hickory is a common name for trees composing the genus ''Carya'', which includes around 18 species. Five or six species are native to China, Indochina, and India (Assam), as many as twelve are native to the United States, four are found in M ...

, and chestnut

The chestnuts are the deciduous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Castanea'', in the beech family Fagaceae. They are native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

The name also refers to the edible nuts they produce.

The unrelate ...

s may have been important fruit sources; and the latter two, oak, beech

Beech (''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to temperate Europe, Asia, and North America. Recent classifications recognize 10 to 13 species in two distinct subgenera, ''Engleriana'' and ''Fagus''. The ''Engl ...

, elm, and pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family (biology), family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanic ...

honey sources.

The late Miocene was the beginning of a drying trend in Europe. Increasing seasonality and dry spells in the Mediterranean region and the emergence of a Mediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate (also called a dry summer temperate climate ''Cs'') is a temperate climate sub-type, generally characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, fairly wet winters; these weather conditions are typically experienced in the ...

likely caused the replacement of forestland and woodland by open shrubland

Shrubland, scrubland, scrub, brush, or bush is a plant community characterized by vegetation dominated by shrubs, often also including grasses, herbs, and geophytes. Shrubland may either occur naturally or be the result of human activity. It ...

; and the uplift of the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, ...

caused tropical and warm-climate vegetation in Central Europe to retreat in favor of mid-latitude and alpine flora. This likely led to the extinction of great apes in Europe.

See also

References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q131637 Prehistoric apes Miocene primates Fossil taxa described in 1856 Prehistoric primate genera Miocene primates of Europe