Dorothy L Sayers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dorothy Leigh Sayers ( ; 13 June 1893 – 17 December 1957) was an English crime novelist, playwright, translator and critic.

Born in

Other reviewers wrote of a "well-written and pulsating mystery story, with an astonishing number of clues cleverly evolved, and totally unexpected conclusion", and a "pleasantly-going and smartly-written detective story"; another commented, "Miss Sayers is frankly out to thrill us; but her novel is something far other than a typical shocker. Her characters (especially her hero) are very much alive, and she has an admirable narrative style and great constructive skill". With this second novel, Sayers was being compared with the established crime novelist

Other reviewers wrote of a "well-written and pulsating mystery story, with an astonishing number of clues cleverly evolved, and totally unexpected conclusion", and a "pleasantly-going and smartly-written detective story"; another commented, "Miss Sayers is frankly out to thrill us; but her novel is something far other than a typical shocker. Her characters (especially her hero) are very much alive, and she has an admirable narrative style and great constructive skill". With this second novel, Sayers was being compared with the established crime novelist

In 1935 Sayers published what she intended to be the last Wimsey novel, ''Gaudy Night'', set in Harriet Vane's old Oxford college. There is attempted murder but Wimsey identifies the culprit in time to prevent further harm. At the end of the book Wimsey proposes to Harriet (in Latin) and is accepted (also in Latin). In Oxford in May, and in London in June, Sayers delivered a lecture entitled "Aristotle on Detective Fiction", humorously contending that in his ''Poetics (Aristotle), Poetics'', Aristotle shows that what he most wished for was a good detective story. The same year Sayers worked on a script for a film to be called ''The Silent Passenger''. Although she was promised editorial control, it was not forthcoming and the script was altered; according to her biographer David Coomes, the Wimsey character "looked like a member of the Mafia".

Sayers was growing tired of the solitary vocation of a novelist, and was glad to collaborate with her old university friend Byrne on a new Wimsey story written for the theatre. ''Busman's Honeymoon'', "a detective comedy in three acts", had a short provincial tour before opening in the West End theatre, West End. Sayers, who kept in close contact with her son, John, sent him an account of the demanding rehearsals for the opening, a milieu new to her. The London premiere was at the Harold Pinter Theatre, Comedy Theatre in December 1936. Dennis Arundell and Veronica Turleigh played Wimsey and Harriet. It ran for more than a year, and while it was still running, Sayers rewrote it as a novel, published in 1937, the last of her full-length books featuring Wimsey.

While the play was in rehearsal the organisers of the Canterbury Festival invited Sayers to write a drama for performance in Canterbury Cathedral, following the 1935 staging there of T. S. Eliot's ''Murder in the Cathedral'', and other plays. The result, ''The Zeal of Thy House'', was her dramatisation in blank verse of the life and work of William of Sens, one of the architects of the cathedral. It opened in June 1937, was well reviewed, and made a profit for the festival.

The following year Sayers returned to a religious theme with ''He That Should Come'', a radio Nativity play, broadcast by the BBC on Christmas Day, and in 1939 the Canterbury Festival staged another of her plays, ''The Devil to Pay''. In the same year she published a collection of short stories, ''In the Teeth of the Evidence''—featuring Wimsey, Egg and others—and began a series of articles for ''The Spectator'' called ''The Wimsey Papers'' between 17 November 1939 and 26 January 1940, using Wimsey and his family and friends to convey Sayers's thoughts on life and politics in the early weeks of the Second World War.

In 1935 Sayers published what she intended to be the last Wimsey novel, ''Gaudy Night'', set in Harriet Vane's old Oxford college. There is attempted murder but Wimsey identifies the culprit in time to prevent further harm. At the end of the book Wimsey proposes to Harriet (in Latin) and is accepted (also in Latin). In Oxford in May, and in London in June, Sayers delivered a lecture entitled "Aristotle on Detective Fiction", humorously contending that in his ''Poetics (Aristotle), Poetics'', Aristotle shows that what he most wished for was a good detective story. The same year Sayers worked on a script for a film to be called ''The Silent Passenger''. Although she was promised editorial control, it was not forthcoming and the script was altered; according to her biographer David Coomes, the Wimsey character "looked like a member of the Mafia".

Sayers was growing tired of the solitary vocation of a novelist, and was glad to collaborate with her old university friend Byrne on a new Wimsey story written for the theatre. ''Busman's Honeymoon'', "a detective comedy in three acts", had a short provincial tour before opening in the West End theatre, West End. Sayers, who kept in close contact with her son, John, sent him an account of the demanding rehearsals for the opening, a milieu new to her. The London premiere was at the Harold Pinter Theatre, Comedy Theatre in December 1936. Dennis Arundell and Veronica Turleigh played Wimsey and Harriet. It ran for more than a year, and while it was still running, Sayers rewrote it as a novel, published in 1937, the last of her full-length books featuring Wimsey.

While the play was in rehearsal the organisers of the Canterbury Festival invited Sayers to write a drama for performance in Canterbury Cathedral, following the 1935 staging there of T. S. Eliot's ''Murder in the Cathedral'', and other plays. The result, ''The Zeal of Thy House'', was her dramatisation in blank verse of the life and work of William of Sens, one of the architects of the cathedral. It opened in June 1937, was well reviewed, and made a profit for the festival.

The following year Sayers returned to a religious theme with ''He That Should Come'', a radio Nativity play, broadcast by the BBC on Christmas Day, and in 1939 the Canterbury Festival staged another of her plays, ''The Devil to Pay''. In the same year she published a collection of short stories, ''In the Teeth of the Evidence''—featuring Wimsey, Egg and others—and began a series of articles for ''The Spectator'' called ''The Wimsey Papers'' between 17 November 1939 and 26 January 1940, using Wimsey and his family and friends to convey Sayers's thoughts on life and politics in the early weeks of the Second World War.

In 1950 Sayers was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Letters by the University of Durham. After years of declining health her husband Mac died at their home in Witham in June 1950. The following year, for the Festival of Britain, she wrote her last play, ''The Emperor Constantine'', described by ''The Stage'' as "long, rambling, episodic, and wholly absorbing".

Sayers made a last foray into crime fiction in 1953 with ''No Flowers By Request'', another collaborative serial, published in ''The Daily Sketch'', co-written with E. C. R. Lorac, Anthony Gilbert (writer), Anthony Gilbert, Gladys Mitchell and Christianna Brand. The following year she published ''Introductory Papers on Dante'', and in 1955 Penguin Books published ''Purgatory'', the second volume of her translation of ''The Divine Comedy''. Like its predecessor, it enjoyed substantial sales. The last books by Sayers were ''The Song of Roland'', translated from the French, and a second volume of papers on Dante (both 1957).

On 17 December 1957 Sayers died suddenly of a coronary thrombosis at her home in Witham, aged 64; she was cremated six days later at Golders Green Crematorium. Her ashes were buried at the base of the tower of St Anne's Church, Soho. Her translation of the third and final volume of ''The Divine Comedy'', two-thirds complete, was finished by

In 1950 Sayers was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Letters by the University of Durham. After years of declining health her husband Mac died at their home in Witham in June 1950. The following year, for the Festival of Britain, she wrote her last play, ''The Emperor Constantine'', described by ''The Stage'' as "long, rambling, episodic, and wholly absorbing".

Sayers made a last foray into crime fiction in 1953 with ''No Flowers By Request'', another collaborative serial, published in ''The Daily Sketch'', co-written with E. C. R. Lorac, Anthony Gilbert (writer), Anthony Gilbert, Gladys Mitchell and Christianna Brand. The following year she published ''Introductory Papers on Dante'', and in 1955 Penguin Books published ''Purgatory'', the second volume of her translation of ''The Divine Comedy''. Like its predecessor, it enjoyed substantial sales. The last books by Sayers were ''The Song of Roland'', translated from the French, and a second volume of papers on Dante (both 1957).

On 17 December 1957 Sayers died suddenly of a coronary thrombosis at her home in Witham, aged 64; she was cremated six days later at Golders Green Crematorium. Her ashes were buried at the base of the tower of St Anne's Church, Soho. Her translation of the third and final volume of ''The Divine Comedy'', two-thirds complete, was finished by

"Sayers, Dorothy Leigh"

''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'', Oxford University Press, 2022 Wooding writes that Sayers was loosely associated with several other representatives of "what might be called lay orthodoxy", including C. S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and T. S. Eliot, writing before and after the Second World War. Sayers insisted in an article titled "Playwrights are Not Evangelists" that her purpose was not to proselytise. Her view of theological aesthetics was that a work of art will speak to its audience only if the artist serves the work rather than trying to preach. She said that her motive in writing ''The Man Born to Be King'' was not "to do good", but to tell the story to the best of her ability ... "in short, to make as good a work of art as I could". In a 2017 study for the Ecclesiastical History Society, Margaret Wiedemann Hunt writes that ''The Man Born to Be King'' was "an astonishing and far-reaching innovation", not only because it used colloquial speech and because Jesus was portrayed by an actor (something not then permitted in theatres in Britain), but also because "it brought the gospels into people's lives in a way that demanded an imaginative response". In preparation for writing the cycle, Sayers made her own translations of the Gospels from the original Greek into modern English; she hoped to persuade listeners that the 17th-century King James version was over-familiar to churchgoers and incomprehensible to everyone else. In a 1984 study of religious broadcasting in Britain, Kenneth Wolfe writes of ''The Man Born to Be King'', "That it was the most astonishing and far-reaching innovation in all religious broadcasting so far is beyond dispute".

Sayers's 1949 translation of Dante's ''Inferno (Dante), Hell'' was a best-seller: its first print run of 50,000 quickly sold out.Reynolds (1999), p. 3 Cantica 2 of ''The Divine Comedy'', ''Purgatorio, Purgatory'', was published in 1955, but when Sayers died her version of the final Cantica, ''Paradiso (Dante), Heaven'', was only two-thirds complete. Reynolds finished the translation and it was published in 1962. The three volumes of the Sayers translation sold 1.25 million copies by 1999. Writing in 1989 Reynolds noted that because of Sayers's translations, Dante has been read by "more English-speaking readers in the last forty years than he had in the preceding six and a quarter centuries".

For her translation Sayers chose to use modern colloquial English, and as she described, "to eschew 'Marry, quotha!' without declining upon 'Sez you!'". Where she differed from this was in ''Purgatory'', where Dante used Provençal dialect, the dialect of Provence for the words of the southern French poet Arnaut Daniel: Sayers instead used a Southern Scots dialect and explained it was "a dialect which bears something of the same relation to English as Provençal does to Italian". Sayers's biographer Mary Brian Durkin observes that "many find her translation of the passage jarring and distracting", while Durkin thinks it "forced ... almost wikt:doggerel#Adjective, doggerel".

Sayers retained Dante's structure—Tercet, three-line stanzas linked by their rhyme scheme—a difficult form to use in English translations, given the fewer rhyme endings when compared with Italian. The theological academic Mary Prentice Barrows considers that when the form is used in English translations of Dante, including those by Sayers, "the necessity of fitting the exact sense into triple rhymes inevitably forces distorted syntax and strange choices of words, so that the limpidity—the characteristic beauty of the original—is lost". Thomas G. Bergin, a scholar of Italian literature who had also translated ''The Divine Comedy'', thought that Sayers's translation has "the directness of Dante in tone, and the very technique of Dante in execution. And indeed the merits of Miss Sayers's version are great."Bergin, p. 12 Although, he noted, the limitations of the form meant some of Sayers's rhymes were forced. The critic Dudley Fitts criticised Sayers's use of ''terza rima'' in English, and her use of some archaisms for the sake of rhyme which "are so nearly pervasive that they reduce the impact of a work generously conceived and lovingly elaborated".Fitts, Dudley. "An Urge to Make Dante Known", ''The New York Times'', 6 November 1955, section BR, p. 5 In the introduction to ''Purgatory'', Sayers advised readers to

Reynolds considers Sayers was well placed to deal with Dante's rhyming structure. She had been interested in translating poetry from her schooldays and had enjoyed writing her own early verses. Her first works of poetry, according to Reynolds, contain "a masterly and beautiful example of a lay, a series of poems linked to a complex structure". Fitts considers her "not ... an accomplished poet; but she does handle verse intelligently". With each of the Dante translations, Sayers included detailed introductions to explain her word choices and to provide alternative translations. Notes were included on each canto to explain the allegories and symbology; the writer Anne Perry considers these "acutely satisfying and thought provoking and infinitely enriching the work".Perry, pp. 109–110 Sayers also provided an outline on Dante's life and personality, "without which", in Perry's view, "the whole work would be robbed of much of its meaning".

Sayers's 1949 translation of Dante's ''Inferno (Dante), Hell'' was a best-seller: its first print run of 50,000 quickly sold out.Reynolds (1999), p. 3 Cantica 2 of ''The Divine Comedy'', ''Purgatorio, Purgatory'', was published in 1955, but when Sayers died her version of the final Cantica, ''Paradiso (Dante), Heaven'', was only two-thirds complete. Reynolds finished the translation and it was published in 1962. The three volumes of the Sayers translation sold 1.25 million copies by 1999. Writing in 1989 Reynolds noted that because of Sayers's translations, Dante has been read by "more English-speaking readers in the last forty years than he had in the preceding six and a quarter centuries".

For her translation Sayers chose to use modern colloquial English, and as she described, "to eschew 'Marry, quotha!' without declining upon 'Sez you!'". Where she differed from this was in ''Purgatory'', where Dante used Provençal dialect, the dialect of Provence for the words of the southern French poet Arnaut Daniel: Sayers instead used a Southern Scots dialect and explained it was "a dialect which bears something of the same relation to English as Provençal does to Italian". Sayers's biographer Mary Brian Durkin observes that "many find her translation of the passage jarring and distracting", while Durkin thinks it "forced ... almost wikt:doggerel#Adjective, doggerel".

Sayers retained Dante's structure—Tercet, three-line stanzas linked by their rhyme scheme—a difficult form to use in English translations, given the fewer rhyme endings when compared with Italian. The theological academic Mary Prentice Barrows considers that when the form is used in English translations of Dante, including those by Sayers, "the necessity of fitting the exact sense into triple rhymes inevitably forces distorted syntax and strange choices of words, so that the limpidity—the characteristic beauty of the original—is lost". Thomas G. Bergin, a scholar of Italian literature who had also translated ''The Divine Comedy'', thought that Sayers's translation has "the directness of Dante in tone, and the very technique of Dante in execution. And indeed the merits of Miss Sayers's version are great."Bergin, p. 12 Although, he noted, the limitations of the form meant some of Sayers's rhymes were forced. The critic Dudley Fitts criticised Sayers's use of ''terza rima'' in English, and her use of some archaisms for the sake of rhyme which "are so nearly pervasive that they reduce the impact of a work generously conceived and lovingly elaborated".Fitts, Dudley. "An Urge to Make Dante Known", ''The New York Times'', 6 November 1955, section BR, p. 5 In the introduction to ''Purgatory'', Sayers advised readers to

Reynolds considers Sayers was well placed to deal with Dante's rhyming structure. She had been interested in translating poetry from her schooldays and had enjoyed writing her own early verses. Her first works of poetry, according to Reynolds, contain "a masterly and beautiful example of a lay, a series of poems linked to a complex structure". Fitts considers her "not ... an accomplished poet; but she does handle verse intelligently". With each of the Dante translations, Sayers included detailed introductions to explain her word choices and to provide alternative translations. Notes were included on each canto to explain the allegories and symbology; the writer Anne Perry considers these "acutely satisfying and thought provoking and infinitely enriching the work".Perry, pp. 109–110 Sayers also provided an outline on Dante's life and personality, "without which", in Perry's view, "the whole work would be robbed of much of its meaning".

From the outset, Sayers aimed to develop the detective novel from the pure puzzle into a less artificial style, comparable with non-crime fiction of the period. A later writer of crime novels, P. D. James, writes that Sayers "did as much as any writer in the genre to develop the detective story from an ingenious but lifeless puzzle into an intellectually respectable branch of fiction with serious claims to be judged as a novel".Brabazon, p. xiv As a reviewer Sayers wrote of one book by a now neglected writer, A. E. Fielding, "The plot is extremely intricate and full of red herrings, and the solution is kept a dark secret up to the last moment. The weakness ... is that the people never really come alive." She admired Agatha Christie, but in her own works Sayers moved away to some extent from the traditional whodunit towards what has been dubbed the "howdunit": "There is still an idea going about that the 'Who?' book is the only legitimate variety of the species. Yet, if we demand any sort of likeness to real life, the 'How?' book is much nearer to the facts".Sayers and Edwards, pp. 16 and 21 James notes that Sayers nonetheless wrote within the "Golden Age" conventions, with a central mystery, a closed circle of suspects and a solution that the reader can work out by logical deduction from clues "planted with deceptive cunning but essential fairness ... Those were not the days of the swift bash to the skull followed by 60,000 words of psychological insight".

Some of Sayers's stories have been filmed for the cinema and television. Robert Montgomery (actor), Robert Montgomery and Constance Cummings played Wimsey and Harriet Vane in a Busman's Honeymoon (film), 1940 film adaptation of ''Busman's Honeymoon'', and for BBC television Ian Carmichael played Wimsey in serial adaptations of six of the novels (none of them featuring Vane), broadcast between 1972 and 1975. Edward Petherbridge played Wimsey and Harriet Walter played Vane in television versions of ''Strong Poison'', ''Have His Carcase'' and ''Gaudy Night'' in 1987. On BBC radio, in numerous adaptations of Sayers's detective stories, Wimsey has been played by more than a dozen actors, including Rex Harrison, Hugh Burden, Alan Wheatley, Ian Carmichael and Gary Bond. New productions of ''The Man Born to Be King'' were broadcast in every decade from the 1940s to the 1970s, and the cycle was repeated in the first and second decades of the 21st century.

In 1998, at the invitation of Sayers's estate, Jill Paton Walsh published a completion of an unfinished Wimsey novel, ''Thrones, Dominations'', which Sayers began in 1936 but abandoned after six chapters. It was well received—''The Times'' found it "miraculously right" with "a thrilling denouement"—and Paton Walsh wrote three more Wimsey novels. ''A Presumption of Death'' (2002) incorporated extracts from ''The Wimsey Papers'' published by Sayers in 1939 and 1940. ''The Attenbury Emeralds'' (2010) was based on Wimsey's first case, referred to in a number of Sayers's novels; in ''The Times'', Marcel Berlins said that Sayers would not have recognised that the book was not her own work. In ''The Late Scholar'' (2013), Peter and Harriet, now Duke and Duchess of Denver, visit the fictional St Severin's College, Oxford, where Peter is Visitor.

In 1973 the minor planet 3627 Sayers was named after her. The asteroid was discovered by Luboš Kohoutek, but the name was suggested by the astronomer Brian G. Marsden, with whom Sayers consulted extensively during the last year of her life, in her attempt to rehabilitate the Roman poet Lucan. Sayers has a feast day on 17 December in the American Calendar of saints (Episcopal Church), Episcopal Church liturgical calendar, given because of her work as a Christian apologist and spiritual writer. In 2000 English Heritage installed a blue plaque at 24 Great James Street, Bloomsbury, where Sayers lived between 1921 and 1929. The Dorothy L. Sayers Society was founded in 1976 and, as at 2024, continues in its mission "to promote the study of the life, works and thoughts of this great scholar and writer, to encourage the performance of her plays and the publication of books by and about her, to preserve original material for posterity and to provide assistance for researchers".

From the outset, Sayers aimed to develop the detective novel from the pure puzzle into a less artificial style, comparable with non-crime fiction of the period. A later writer of crime novels, P. D. James, writes that Sayers "did as much as any writer in the genre to develop the detective story from an ingenious but lifeless puzzle into an intellectually respectable branch of fiction with serious claims to be judged as a novel".Brabazon, p. xiv As a reviewer Sayers wrote of one book by a now neglected writer, A. E. Fielding, "The plot is extremely intricate and full of red herrings, and the solution is kept a dark secret up to the last moment. The weakness ... is that the people never really come alive." She admired Agatha Christie, but in her own works Sayers moved away to some extent from the traditional whodunit towards what has been dubbed the "howdunit": "There is still an idea going about that the 'Who?' book is the only legitimate variety of the species. Yet, if we demand any sort of likeness to real life, the 'How?' book is much nearer to the facts".Sayers and Edwards, pp. 16 and 21 James notes that Sayers nonetheless wrote within the "Golden Age" conventions, with a central mystery, a closed circle of suspects and a solution that the reader can work out by logical deduction from clues "planted with deceptive cunning but essential fairness ... Those were not the days of the swift bash to the skull followed by 60,000 words of psychological insight".

Some of Sayers's stories have been filmed for the cinema and television. Robert Montgomery (actor), Robert Montgomery and Constance Cummings played Wimsey and Harriet Vane in a Busman's Honeymoon (film), 1940 film adaptation of ''Busman's Honeymoon'', and for BBC television Ian Carmichael played Wimsey in serial adaptations of six of the novels (none of them featuring Vane), broadcast between 1972 and 1975. Edward Petherbridge played Wimsey and Harriet Walter played Vane in television versions of ''Strong Poison'', ''Have His Carcase'' and ''Gaudy Night'' in 1987. On BBC radio, in numerous adaptations of Sayers's detective stories, Wimsey has been played by more than a dozen actors, including Rex Harrison, Hugh Burden, Alan Wheatley, Ian Carmichael and Gary Bond. New productions of ''The Man Born to Be King'' were broadcast in every decade from the 1940s to the 1970s, and the cycle was repeated in the first and second decades of the 21st century.

In 1998, at the invitation of Sayers's estate, Jill Paton Walsh published a completion of an unfinished Wimsey novel, ''Thrones, Dominations'', which Sayers began in 1936 but abandoned after six chapters. It was well received—''The Times'' found it "miraculously right" with "a thrilling denouement"—and Paton Walsh wrote three more Wimsey novels. ''A Presumption of Death'' (2002) incorporated extracts from ''The Wimsey Papers'' published by Sayers in 1939 and 1940. ''The Attenbury Emeralds'' (2010) was based on Wimsey's first case, referred to in a number of Sayers's novels; in ''The Times'', Marcel Berlins said that Sayers would not have recognised that the book was not her own work. In ''The Late Scholar'' (2013), Peter and Harriet, now Duke and Duchess of Denver, visit the fictional St Severin's College, Oxford, where Peter is Visitor.

In 1973 the minor planet 3627 Sayers was named after her. The asteroid was discovered by Luboš Kohoutek, but the name was suggested by the astronomer Brian G. Marsden, with whom Sayers consulted extensively during the last year of her life, in her attempt to rehabilitate the Roman poet Lucan. Sayers has a feast day on 17 December in the American Calendar of saints (Episcopal Church), Episcopal Church liturgical calendar, given because of her work as a Christian apologist and spiritual writer. In 2000 English Heritage installed a blue plaque at 24 Great James Street, Bloomsbury, where Sayers lived between 1921 and 1929. The Dorothy L. Sayers Society was founded in 1976 and, as at 2024, continues in its mission "to promote the study of the life, works and thoughts of this great scholar and writer, to encourage the performance of her plays and the publication of books by and about her, to preserve original material for posterity and to provide assistance for researchers".

The Dorothy L. Sayers Society

* ; Archives

Dorothy Sayers archives at the Marion E. Wade Center

at Wheaton College (Illinois), Wheaton College

Dorothy L. Sayers letters and poems

at the Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College Special Collections * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sayers, Dorothy L. Dorothy L. Sayers, 1893 births 1957 deaths 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English women writers 20th-century English translators Alumni of Somerville College, Oxford Anglican writers British copywriters Burials at St Anne's Church, Soho Christian apologists Christian humanists Christian novelists Churchwardens British critics of atheism Critics of work and the work ethic Deaths from coronary thrombosis English Anglicans English crime fiction writers English dramatists and playwrights English feminist writers English mystery writers English women dramatists and playwrights English women novelists French–English translators Italian–English translators Lay theologians Members of the Detection Club People educated at Christ Church Cathedral School People educated at Godolphin School People from Bluntisham Sherlock Holmes scholars Translators of Dante Alighieri English women mystery writers English women religious writers Writers from Essex Writers from Oxford Writers of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction

Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, Sayers was brought up in rural East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

and educated at Godolphin School

Godolphin School is a Private schools in the United Kingdom, private boarding school, boarding and day school for girls in Salisbury, England, which was founded in 1726 and opened in 1784. The school educates girls between the ages of three an ...

in Salisbury

Salisbury ( , ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers River Avon, Hampshire, Avon, River Nadder, Nadder and River Bourne, Wi ...

and Somerville College

Somerville College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It was founded in 1879 as Somerville Hall, one of its first two women's colleges. It began admitting men in 1994. The college's liberal tone derives from its f ...

, Oxford, graduating with first class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure used for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied, sometimes with significant var ...

in medieval French

Old French (, , ; ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France approximately between the late 8th -4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk of the beginnings of French, that is, when it wa ...

. She worked as an advertising copywriter between 1922 and 1929 before success as an author brought her financial independence. Her first novel, ''Whose Body?

''Whose Body?'' is a 1923 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers first published in the UK by T. Fisher Unwin and in the US by Boni & Liveright. It was her debut novel, and the book in which she introduced the character of Lord Peter Wimsey. ''Clou ...

'', was published in 1923. Between then and 1939 she wrote ten more novels featuring the upper-class amateur sleuth Lord Peter Wimsey

Lord Peter Death Bredon Wimsey (later 17th Duke of Denver) is the fictional protagonist in a series of detective novels and short stories by Dorothy L. Sayers (and their continuation by Jill Paton Walsh). A amateur, dilettante who solves myst ...

. In 1930, in ''Strong Poison

''Strong Poison'' is a 1930 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, her fifth featuring Lord Peter Wimsey and the first in which Harriet Vane appears.

Plot

The novel opens with mystery author Harriet Vane on trial for the murder of her former lo ...

'', she introduced a leading female character, Harriet Vane, the object of Wimsey's love. Harriet appears sporadically in future novels, resisting Lord Peter's proposals of marriage until ''Gaudy Night

''Gaudy Night'' (1935) is a mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, the tenth featuring Lord Peter Wimsey, and the third including Harriet Vane.

The dons of Harriet Vane's ''alma mater'', the all-female Shrewsbury College, Oxford (based on Say ...

'' in 1935, six novels later.

Sayers moved the genre of detective fiction away from pure puzzles lacking characterisation or depth, and became recognised as one of the four "Queens of Crime" of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction

The Golden Age of Detective Fiction was an era of classic murder mystery novels of similar patterns and styles, predominantly in the 1920s and 1930s. While the Golden Age proper is usually taken to refer to works from that period, this type of f ...

of the 1920s and 1930s, along with Agatha Christie

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, Lady Mallowan, (; 15 September 1890 – 12 January 1976) was an English people, English author known for her 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections, particularly those revolving ...

, Margery Allingham

Margery Louise Allingham (20 May 1904 – 30 June 1966) was an English novelist from the "Golden Age of Detective Fiction", and considered one of its four " Queens of Crime", alongside Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers and Ngaio Marsh.

All ...

and Ngaio Marsh

Dame Edith Ngaio Marsh ( ; 23 April 1895 – 18 February 1982) was a New Zealand mystery writer, writer.

As a crime writer during the "Golden Age of Detective Fiction", Marsh is known as one of the Detective fiction#Golden Age detective novel ...

. She was a founder member of the Detection Club

The Detection Club was formed in 1930 by a group of British mystery writers, including Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Ronald Knox, Freeman Wills Crofts, Arthur Morrison, Hugh Walpole, John Rhode, Jessie Louisa Rickard, Baroness Orczy, ...

, and worked with many of its members in producing novels and radio serials collaboratively, such as the novel ''The Floating Admiral

''The Floating Admiral'' is a chain-written, collaborative detective novel written by fourteen members of the British Detection Club in 1931. The twelve chapters of the story were each written by a different author, in the following sequence: ...

'' in 1931.

From the mid‐1930s Sayers wrote plays, mostly on religious themes; they were performed in English cathedrals and broadcast by the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

. Her radio dramatisation of the life of Jesus, ''The Man Born to Be King

''The Man Born to Be King'' is a radio drama based on the life of Jesus, produced and broadcast by the BBC during the Second World War. It is a play cycle consisting of twelve plays depicting specific periods in Jesus' life, from the events s ...

'' (1941–42), initially provoked controversy but was quickly recognised as an important work. From the early 1940s her main preoccupation was translating the three books of Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

's ''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' (, ) is an Italian narrative poetry, narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of ...

'' into colloquial English. She died unexpectedly at her home in Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

, aged 64, before completing the third book.

Life and career

Early years

Sayers was born on 13 June 1893 at the Old Choir House inBrewer Street, Oxford

Brewer Street is a historic narrow street in central Oxford, England, south of Carfax.

The street runs east–west, connecting with St Aldate's to the east and St Ebbe's Street to the west.

History

Originally, the area was occupied by but ...

; she was the only child of the Henry Sayers and his wife Helen "Nell" Mary, Leigh.Reynolds (1993), p. 3 Henry Sayers, born at Tittleshall

Tittleshall is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk.Ordnance Survey (1999). ''OS Explorer Map 238 - East Dereham & Aylsham''. .

Location

The village and parish of Tittleshall has an area of 1376 hectares or . The parish ...

, Norfolk, was the son of the Rev Robert Sayers, from County Tipperary

County Tipperary () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. The county is named after the town of Tipperary (tow ...

, Ireland. At the time of Sayers's birth her father was headmaster of Christ Church Cathedral School

Christ Church Cathedral School is an independent preparatory school for boys in Oxford, England. It is one of three choral foundation schools in the city and educates choristers of Christ Church Cathedral, and the Chapels of Worcester College ...

and chaplain of Christ Church, one of the colleges of the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford has 36 colleges within universities in the United Kingdom#Traditional collegiate universities, colleges, three societies, and four permanent private halls (PPHs) of religious foundation. The colleges and PPHs are autonom ...

.Reynolds (1993), p. 1 Her mother, born in Shirley

Shirley may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Shirley'' (novel), an 1849 novel by Charlotte Brontë

* ''Shirley'' (1922 film), a British silent film

* ''Shirley'' (2020 film), an American biographical film about Shirley Jackson

* ''Shirley'' ( ...

, Hampshire, was a daughter of a solicitor descended from landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the gentry (sometimes collectively known as the squirearchy), is a largely historical Irish and British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. It is t ...

on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (Help:IPA/English, /waɪt/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''WYTE'') is an island off the south coast of England which, together with its surrounding uninhabited islets and Skerry, skerries, is also a ceremonial county. T ...

. Sayers was proud of the Leigh connection and later considered calling herself "D. Leigh Sayers" in professional matters, before settling for "Dorothy L. Sayers"—insisting on the inclusion of the middle initial.

When Sayers was four years old her father accepted the post of rector of Bluntisham-cum-Earith in the Fen Country of East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

. The appointment carried a better stipend

A stipend is a regular fixed sum of money paid for services or to defray expenses, such as for scholarship, internship, or apprenticeship. It is often distinct from an income or a salary because it does not necessarily represent payment for work pe ...

than the Christ Church posts and the large rectory

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of a given religion, serving as both a home and a base for the occupant's ministry. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, p ...

had considerably more room than the family's house in Oxford, but the move cut them off from the city's lively social scene. This affected the rector and his wife differently: he was scholarly and self-effacing; she, like many of the Leigh family—including her great-uncle Percival Leigh, a contributor to the humorous magazine '' Punch''—was outgoing and gregarious and she missed the stimulation of Oxford society.Brabazon, p. 5; and Reynolds (1993), p. 3

In the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

'' (ODNB), Catherine Kenney writes that the lack of siblings and neighbouring children of her own age or class made Sayers's childhood fairly solitary, although her parents were loving and attentive. Sayers formed one lasting friendship in these years: Ivy Shrimpton, eight years her senior, her first cousin as Nell's niece. Shrimpton, raised in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

as an infant but educated in an Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

convent school in Oxford, made extended visits to the Bluntisham rectory. Kenney writes that the two formed a lifelong friendship through "a youthful sharing of books, imagination, and confidences". Otherwise, Kenney comments, Sayers, "like many future authors ... lived largely a life of books and stories". She could read by the age of four, and made full use of her father's extensive library as she grew up.

Schooling

Sayers was educated chiefly at home. Her father began teaching her Latin before she was seven, and she had lessons from governesses in other subjects, including French and German. In January 1909, when she was fifteen, her parents sent her toGodolphin School

Godolphin School is a Private schools in the United Kingdom, private boarding school, boarding and day school for girls in Salisbury, England, which was founded in 1726 and opened in 1784. The school educates girls between the ages of three an ...

, a boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. They have existed for many centuries, and now extend acr ...

in Salisbury

Salisbury ( , ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers River Avon, Hampshire, Avon, River Nadder, Nadder and River Bourne, Wi ...

. Her biographer Barbara Reynolds

Eva Mary Barbara Reynolds (13 June 1914 – 29 April 2015) was an English scholar of Italian Studies, lexicographer and translator. She wrote and edited several books concerning Dorothy Sayers and was president of the Dorothy L. Sayers Soc ...

writes that Sayers took a lively part in the life of the school, acting in plays, some of which she wrote and produced herself, singing (sometimes solo), playing the violin and the viola in the school orchestra and forming highly charged friendships.

Despite some excellent teachers, Sayers was not happy at the school. Joining at the age of fifteen, rather than the school's normal starting age of eight, she was seen as an outsider by some of the other girls, and not all the staff approved of her independence of mind. As an Anglican with strong high-church

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, nd sacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although used in connection with various Christia ...

views, she was repelled by the form of Christianity practised at Godolphin, described by her biographer James Brabazon as "a low-church pietism

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christianity, Christian life.

Although the movement is ali ...

, drab and mealy-mouthed", which came close to putting her off religion completely.

During an outbreak of measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

at the school in 1911 Sayers nearly died. Her mother was allowed to stay at the school, where she nursed her daughter, who recovered in time to study and sit for a Gilchrist Scholarship, which she was awarded in March 1912."Somerville College, Oxford", ''The Times'', 30 March 1912, p. 7; and Sayers and Reynolds, p. 64 Among the purposes of these scholarships was to sponsor women to study at university colleges. Sayers's scholarship, worth £50 a year for three years, enabled her to study modern languages at Somerville College, Oxford

Somerville College is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It was founded in 1879 as Somerville Hall, one of its first two women's colleges. It began admitting men in 1994. The colle ...

. After her experiences with the religious regime at Godolphin, Sayers chose Somerville, a non-denominational college, instead of an Anglican college.

Oxford

The all-women college of Somerville suited well, according to Kenney, because of its practice of cultivating its students to take prominent roles in the arts and public life. She enjoyed her time there, and, she later said, acquired a scholarly method and habit of mind which served her throughout her life. She was a distinguished student, and, in Kenney's view, Sayers's novels and essays reflect her liberal education at Oxford. Among the lifelong friends she made at Somerville was Muriel St Clare Byrne, who later played an important part in Sayers's career and became herliterary executor

The literary estate of a deceased author consists mainly of the copyright and other intellectual property rights of published works, including film rights, film, translation rights, original manuscripts of published work, unpublished or partially ...

.

Sayers was co-founder, with Amphilis Middlemore and Charis Ursula Barnett, of the Mutual Admiration Society, a literary society

A literary society is a group of people interested in literature. In the modern sense, this refers to a society that wants to promote one genre of writing or a specific author. Modern literary societies typically promote research, publish newslet ...

where female students would read and critique each other's work. Sayers gave the group its name, remarking, "if we didn't give ourselves that title, the rest of College would". The society was a forerunner of the Inklings

The Inklings were an informal literary discussion group associated with J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis at the University of Oxford for nearly two decades between the early 1930s and late 1949. The Inklings were literary enthusiasts who prai ...

, the informal literary discussion group at Oxford; Sayers never belonged to the latter—an all-male group of writers—but became friendly with C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer, literary scholar and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Magdalen College, Oxford (1925–1954), and Magdalen ...

and other members.

Sayers, who was considered to have a good contralto

A contralto () is a classical music, classical female singing human voice, voice whose vocal range is the lowest of their voice type, voice types.

The contralto's vocal range is fairly rare, similar to the mezzo-soprano, and almost identical to ...

voice, joined the Oxford Bach Choir

The Oxford Bach Choir is an amateur choir based in Oxford, England. Founded by Basil Harwood in 1896 to further the music of J. S. Bach in Oxford, the Choir merged in 1905 with the Oxford Choral & Philharmonic Society, whose origins can be tr ...

and developed an unrequited passion for its director, Hugh Allen. Later in her time at Oxford, she became attracted to a fellow student named Roy Ridley, later chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intellige ...

of Balliol, on whose appearance and manner she later drew for her best-known character, Lord Peter Wimsey

Lord Peter Death Bredon Wimsey (later 17th Duke of Denver) is the fictional protagonist in a series of detective novels and short stories by Dorothy L. Sayers (and their continuation by Jill Paton Walsh). A amateur, dilettante who solves myst ...

. She studied diligently, with the encouragement of her tutor, Mildred Pope

Mildred Katherine Pope (28 January 1872 – 16 September 1956) was an English scholar of Anglo-Norman England. She became the first woman to hold a readership at Oxford University, where she taught at Somerville College.

Biography

Mildred Pope w ...

, and in 1915 she was awarded first class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure used for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied, sometimes with significant var ...

in what was termed modern (in fact medieval) French in her final examinations. Despite her examination results, she was ineligible to be awarded a degree, as Oxford did not formally confer them on women. When the university changed its rules in 1920, Sayers was among the first to have her degree officially awarded.

Early employment and first novel, 1916–1924

After graduating from Oxford, Sayers, who had begun writing verse in childhood, brought out two slim volumes of poetry, ''Op. I'' (1916) and ''Catholic Tales and Christian Songs'' (1918). To earn a living she taught modern languages at Hull High School for Girls. Teaching did not greatly appeal to her, and in 1917 she secured a post with the publisher and booksellerBasil Blackwell

Sir Basil Henry Blackwell (29 May 18899 April 1984) was an English bookseller.

Biography

Blackwell was born in Oxford, England. He was the son of Benjamin Henry Blackwell (18491924), founder of Blackwell's bookshop in Oxford, which went on to beco ...

in Oxford. Returning to the city suited her well. A younger contemporary, Doreen Wallace

Dora Eileen Agnew Rash (née Wallace; 18 June 1897 – 22 October 1989), known as Doreen Wallace, was an English novelist, grammar school teacher and social campaigner.Norfolk Women in HistorRetrieved 17 September 2018 In more than 40 novels she ...

, later described her in these years:

The post with Blackwell lasted for two years, after which Sayers moved to France. She was engaged in 1919 by a school near Verneuil-sur-Avre

Verneuil-sur-Avre (, literally ''Verneuil on Avre (Eure), Avre'') is a former Communes of France, commune in the Eure Departments of France, department in Normandy (administrative region), Normandy in northern France. On 1 January 2017, it was me ...

in Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

as assistant to Eric Whelpton, who was teaching English there. She had been in love with him at Oxford, and he was among the models for the appearance and character of Wimsey. In 1921 Sayers returned to London, accepted a teaching position with a girls' school in Acton, London

Acton () is a town in West London, England, within the London Borough of Ealing. It is west of Charing Cross.

At the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 census, its four Wards of the United Kingdom, wards, East Acton, Acton Central, South Acton ...

, and began a relationship with a fellow writer, John Cournos

John Cournos, born Ivan Grigorievich Korshun () (6 March 1881 – 27 August 1966), was an American writer and translator.

Biography

Cournos was born into a Russian Jewish family in Zhytomyr, Russian Empire (now in Ukraine). His first language wa ...

. The affair was intense and lasted until October 1922 when Cournos left the country.Brabazon, pp. 94–96

In 1922 Sayers took a job as a copywriter

Copywriting is the act or occupation of writing text for the purpose of advertising or other forms of marketing. Copywriting is aimed at selling products or services. The product, called copy or sales copy, is written content that aims to incre ...

at S. H. Benson

S. H. Benson Ltd was a British advertising company founded in 1893 by Samuel Herbert Benson. Clients of the company included Bovril, Guinness and Colmans. S. H. Benson was born on 14 August 1854 in Marylebone.

Naval service

S H Benson served on ...

, then Britain's largest advertising agency. Although she had reservations about the misleading nature of advertising, she became a skilled practitioner, and remained with the firm until the end of 1929. She originated successful campaigns for products including Guinness

Guinness () is a stout that originated in the brewery of Arthur Guinness at Guinness Brewery, St. James's Gate, Dublin, Ireland, in the 18th century. It is now owned by the British-based Multinational corporation, multinational alcoholic bever ...

stout and Colman's

Colman's is an English manufacturer of mustard and other sauces, formerly based and produced for 160 years at Carrow, in Norwich, Norfolk. Owned by Unilever since 1995, Colman's is one of the oldest existing food brands, famous for a limited ra ...

mustard. She is sometimes credited with coining the slogan "My Goodness, My Guinness", but it dates from 1935, more than five years after she left Benson's. She was, though, responsible for the introduction of the Guinness toucan

Toucans (, ) are Neotropical birds in the family Ramphastidae. They are most closely related to the Semnornis, Toucan barbets. They are brightly marked and have large, often colorful Beak, bills. The family includes five genus, genera and over ...

, painted by the artist John Gilroy, for which she penned accompanying verse such as "If he can say as you can/Guinness is good for you/How grand to be a Toucan/Just think what Toucan do". The toucan was used in Guinness's advertisements for decades. Kenney writes that at Benson's, Sayers again enjoyed "some of the fun and camaraderie she had experienced as a student at Oxford".

In her off-duty hours Sayers devoted herself to writing fiction. Detective novels were popular, and Sayers saw an opportunity to produce remunerative, accessible but well-written works in the genre. She mastered the mechanics of the craft by making a close analytical study of the best models. In a biographical sketch, a later crime novelist, J. I. M. Stewart

John Innes Mackintosh Stewart (30 September 1906 – 12 November 1994) was a Scottish novelist and academic. He is equally well known for the works of literary criticism and contemporary novels published under his real name and for the crim ...

, wrote:

The first of Sayers's series of detective novels, ''Whose Body?

''Whose Body?'' is a 1923 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers first published in the UK by T. Fisher Unwin and in the US by Boni & Liveright. It was her debut novel, and the book in which she introduced the character of Lord Peter Wimsey. ''Clou ...

'', featured her amateur detective Lord Peter Wimsey. She had begun writing it before joining Benson's, and it was published in 1923, to mixed reviews; one critic thought it a "somewhat complicated mystery ... clever but crude", and another found the aristocratic Wimsey unconvincing as a detective and the story "a poor specimen of sensationalism

In journalism and mass media, sensationalism is a type of editorial tactic. Events and topics in news stories are selected and worded to excite the greatest number of readers and viewers. This style of news reporting encourages biased or emoti ...

". Some other reviews were more favourable: "the solution does not, as is so often the case, come as an anti-climax to disappoint expectations and lead the reader to feel that he has been 'had' ... We hope to hear from the noble sleuth again"; "We had hardly thought a woman writer could be so robustly gruesome ... a very diverting problem"; "First-rate construction ... a thoroughly satisfactory yarn from start to finish".

Sayers's relationship with Cournos continued until 1922. It remained unconsummated because Cournos did not want children and Sayers refused, for religious reasons, to use contraception. After that affair ended she met a man, Bill White, by whom she had a son in 1924. The novelist A. N. Wilson describes White as "motorcycling rough trade

Rough Trade may refer to:

*Rough Trade (shops), London record stores

*Rough Trade Records, a record label from the stores

*Rough Trade Books, a publishing house from the label

*Rough Trade (band), a Canadian new wave rock band

* "Rough Trade" (''Am ...

". That liaison was short-lived—White turned out to be married—and the son, whom Sayers named John Anthony, was brought up by Ivy Shrimpton, who already had foster children in her care. Sayers concealed her son's parentage from him and from the world in general. She was known to him at first as "Cousin Dorothy", and she later posed as his adoptive mother. Only after her death were the facts made explicit.

Early novels, 1925–1929

''Whose Body?'', published in both Britain and the US, sold well enough for the London publishers, Fisher Unwin, to ask for a sequel. Before that was published Sayers featured Wimsey in a short story, "The Fascinating Problem of Uncle Meleager's Will", published in ''Pearson's Magazine

''Pearson's Magazine'' was a monthly periodical that first appeared in Britain in 1896. A US version began publication in 1899. It specialised in speculative literature, political discussion, often of a socialist bent, and the arts. Its contribu ...

'' in July 1925, which, together with other short stories centred on Wimsey, came out in book form in ''Lord Peter Views the Body

''Lord Peter Views the Body'', first published in 1928, is the first collection of short stories about Lord Peter Wimsey by Dorothy L. Sayers.

Some stories, starting with “The Problem of Uncle Meleager’s Will,” had been previously publi ...

'' in 1928.

''Clouds of Witness

''Clouds of Witness'' is a 1926 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, the second in her series featuring Lord Peter Wimsey. In the United States the novel was first published in 1927 under the title ''Clouds of Witnesses''.

It was adapted for ...

'', the second Wimsey novel, was published in 1926, and was well received. '' The Daily News'' commented:

Other reviewers wrote of a "well-written and pulsating mystery story, with an astonishing number of clues cleverly evolved, and totally unexpected conclusion", and a "pleasantly-going and smartly-written detective story"; another commented, "Miss Sayers is frankly out to thrill us; but her novel is something far other than a typical shocker. Her characters (especially her hero) are very much alive, and she has an admirable narrative style and great constructive skill". With this second novel, Sayers was being compared with the established crime novelist

Other reviewers wrote of a "well-written and pulsating mystery story, with an astonishing number of clues cleverly evolved, and totally unexpected conclusion", and a "pleasantly-going and smartly-written detective story"; another commented, "Miss Sayers is frankly out to thrill us; but her novel is something far other than a typical shocker. Her characters (especially her hero) are very much alive, and she has an admirable narrative style and great constructive skill". With this second novel, Sayers was being compared with the established crime novelist Agatha Christie

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, Lady Mallowan, (; 15 September 1890 – 12 January 1976) was an English people, English author known for her 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections, particularly those revolving ...

as an author of detective stories that were also entertaining novels about human beings.

In the same year Sayers married a divorcé, Captain Oswald Arthur (known as "Mac") Fleming, a well-known journalist. Her son was given the latter's surname but was not brought to live with Sayers and her husband. The marriage, happy at first, grew more difficult as Fleming's health declined, but the couple stayed together until his death of a stroke in 1950, when he was 68.

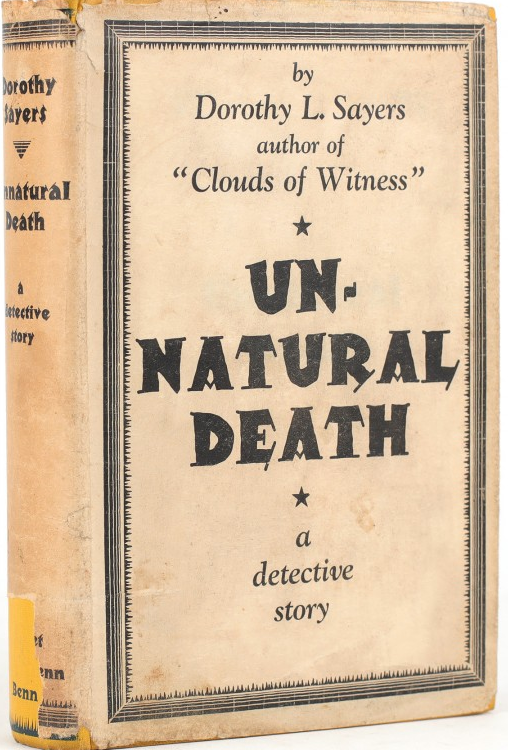

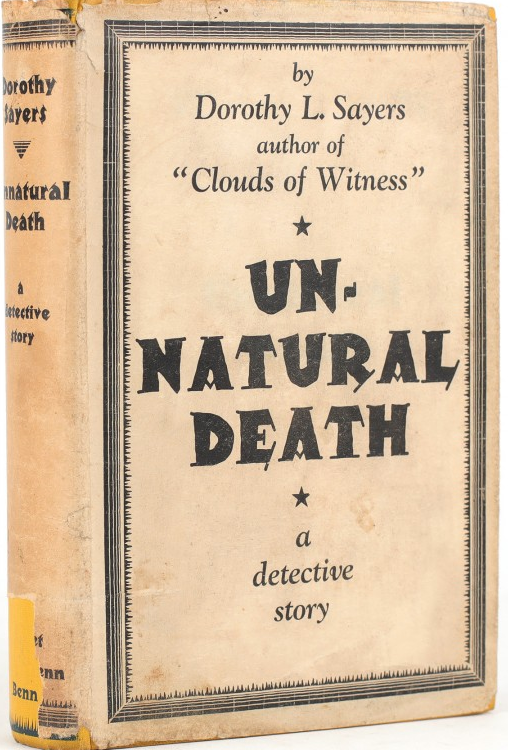

The Wimsey novels continued with ''Unnatural Death

In many legal jurisdictions, the manner of death is a determination, typically made by the coroner, medical examiner, police, or similar officials, and recorded as a vital statistic. Within the United States and the United Kingdom, a distin ...

'' in 1927 and ''The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club

''The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club'' is a 1928 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, her fourth featuring Lord Peter Wimsey. Much of the novel is set in the Bellona Club, a fictional London club for war veterans ( Bellona being a Roman go ...

'' in 1928. In that year Sayers published ''Lord Peter Views the Body'' and edited and introduced an anthology of other writers' works, ''Great Short Stories of Detection, Mystery and Horror'', retitled for its American edition the following year as ''The Omnibus of Crime''.

In 1929, her last year as an employee of Benson's, Sayers and her husband moved from London to the small Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

town of Witham

Witham () is a town and civil parish in the Braintree district, in the county of Essex, England. In the 2011 census, it had a population of 25,353. It is twinned with the town of Waldbröl, Germany. Witham stands on the Roman road between the ...

, which remained their home for the rest of their lives. In that year she published ''Tristan in Brittany'', a verse-and-prose translation of the 12th-century poetic fragments of ''The Romance of Tristan'' by Thomas of Britain

Thomas of Britain (also known as Thomas of England) was a poet of the 12th century. He is known for his Old French poem ''Tristan">-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk of the beginnings of French, that is, w ...

. The scholar George Saintsbury

George Edward Bateman Saintsbury, FBA (23 October 1845 – 28 January 1933), was an English critic, literary historian, editor, teacher, and wine connoisseur. He is regarded as a highly influential critic of the late 19th and early 20th cent ...

wrote an introduction to the book, and Sayers was praised for making a historically important poem available for the first time in modern English.

1930–1934

In 1930 Sayers became a founder member of theDetection Club

The Detection Club was formed in 1930 by a group of British mystery writers, including Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Ronald Knox, Freeman Wills Crofts, Arthur Morrison, Hugh Walpole, John Rhode, Jessie Louisa Rickard, Baroness Orczy, ...

. This grew from informal dinners arranged by Anthony Berkeley

Anthony Berkeley Cox (5 July 1893 – 9 March 1971) was an English crime writer. He wrote under several pen-names, including Francis Iles, Anthony Berkeley and A. Monmouth Platts.

Early life and education

Anthony Berkeley Cox was born 5 July ...

for writers of detective fiction "for the enjoyment of each other's company and for a little shop talk". The dinners proved such a success that the participants agreed to form themselves into a club, under the presidency of G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English author, philosopher, Christian apologist, journalist and magazine editor, and literary and art critic.

Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brow ...

, whom Sayers admired.Brabazon, p. 143 She was one of the club's most enthusiastic members; she devised its elaborate initiation ritual in which new members swore to write without relying on "Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery Pokery, Coincidence or the Act of God" and "to observe a seemly moderation in the use of Gangs, Conspiracies, Death-Rays, Ghosts, Hypnotism, Trap-Doors, Chinamen, Super-Criminals and Lunatics, and utterly and forever to forswear Mysterious Poisons unknown to Science". The club charged no subscription fees, and to raise money for the acquisition of premises members contributed to collaborative works for broadcast or print. The first, organised by Sayers, was ''Behind the Screen

''Behind the Screen'' is a 1916 American silent short comedy film written by, directed by, and starring Charlie Chaplin, and also starring Eric Campbell and Edna Purviance. The film is in the public domain.

Plot

The film takes place in a ...

'' (1930) in which six club members took it in turn to read their own fifteen-minute episodes of a crime mystery on BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

radio.

Sayers published two novels in 1930. Prompted by a suggestion from a fellow author, Robert Eustace

Robert Eustace was the pen name of Eustace Robert Barton (1869–1943), an English doctor and author of mystery and crime fiction with a theme of scientific innovation. He also wrote as Eustace Robert Rawlings. Eustace often collaborated with o ...

, she worked on ''The Documents in the Case

''The Documents in the Case'' is a 1930 novel by Dorothy L. Sayers and Robert Eustace. It is the only one of Sayers's twelve major crime novels not to feature Lord Peter Wimsey, her most famous detective character. However, the forensic analyst ...

''. Eustace, a medical practitioner, provided the main plot device and scientific details; Sayers turned them into prose, hoping to write a novel in the manner of the 19th-century author Wilkie Collins

William Wilkie Collins (8 January 1824 – 23 September 1889) was an English novelist and playwright known especially for ''The Woman in White (novel), The Woman in White'' (1860), a mystery novel and early sensation novel, and for ''The Moonsto ...

, whose work she admired.Reynolds (1993), pp. 221–222 She was working on a biography of Collins and adopted his first-person narrative

A first-person narrative (also known as a first-person perspective, voice, point of view, etc.) is a mode of storytelling in which a storyteller recounts events from that storyteller's own personal point of view, using first-person grammar su ...

technique in a story mostly told in exchanges of letters between the characters. Peter Wimsey does not appear in the book: Brabazon writes that Sayers "tasted the joys of freedom from Wimsey". Reviews were favourable, but gave only qualified praise. In ''The Graphic

''The Graphic'' was a British weekly illustrated newspaper, first published on 4 December 1869 by William Luson Thomas's company, Illustrated Newspapers Ltd with Thomas's brother, Lewis Samuel Thomas, as a co-founder. The Graphic was set up as ...

'', the writer Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires ''Decli ...

contrasted Sayers and Christie:

Sayers was disappointed with the book, and reproached herself for failing to do better with the material provided by her co-author. Her second book of the year was ''Strong Poison

''Strong Poison'' is a 1930 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, her fifth featuring Lord Peter Wimsey and the first in which Harriet Vane appears.

Plot

The novel opens with mystery author Harriet Vane on trial for the murder of her former lo ...

'', in which she introduced the character Harriet Vane, whom Wimsey proves innocent of a murder charge. Sayers originally intended that at the end of the book Wimsey would marry Harriet and retire from detection, ending the series. Financial necessity, however, led the author to write another five Wimsey novels to provide her with a good income before they were eventually betrothed.Brabazon, p. 132 Brabazon describes Harriet as Sayers's alter ego

An alter ego (Latin for "other I") means an alternate Self (psychology), self, which is believed to be distinct from a person's normal or true original Personality psychology, personality. Finding one's alter ego will require finding one's other ...

, sharing many attributes—favourable and otherwise—with the author. Harriet is described by Wimsey's mother as "so interesting and a really remarkable face, though perhaps not strictly good-looking, and all the more interesting for that". The writer Mary Ellen Chase

Mary Ellen Chase (24 February 1887 – 28 July 1973) was an American educator, teacher, scholar, and author. She is regarded as one of the most important regional New England literary figures of the early twentieth century.

Early life

Chase was ...

thought that Sayers had never been conventionally beautiful and after attending one of her lectures in the 1930s, she wrote "There can be few plainer women on earth than Dorothy Sayers utI have never come across one so magnetic to listen to".Hone, p. 79

In 1931 Sayers collaborated with Detection Club colleagues on a longer serial for the BBC, ''The Scoop'', and on a book, ''The Floating Admiral

''The Floating Admiral'' is a chain-written, collaborative detective novel written by fourteen members of the British Detection Club in 1931. The twelve chapters of the story were each written by a different author, in the following sequence: ...

''. She edited a second collection of ''Great Short Stories of Detection, Mystery and Horror'', and as a solo effort wrote ''The Five Red Herrings

''The Five Red Herrings'' (also ''The 5 Red Herrings'') is a 1931 novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, her sixth featuring Lord Peter Wimsey. In the United States it was published in the same year under the title ''Suspicious Characters''.

Plot

The no ...

'', published in the US as ''Suspicious Characters''.Brabazon, p. 298 Harriet Vane does not appear in that novel, but is the central character in the next Wimsey book, ''Have His Carcase

''Have His Carcase'' is a 1932 locked-room mystery by Dorothy L. Sayers, her seventh novel featuring Lord Peter Wimsey and the second in which Harriet Vane appears. It is also included in the 1987 BBC TV series. The book marks a stage in the ...

'', published in 1932. Wimsey solves the murder but is no more successful in winning Harriet's love than he had been in ''Strong Poison''. ''Have His Carcase'' was well received. ''The Scotsman

''The Scotsman'' is a Scottish compact (newspaper), compact newspaper and daily news website headquartered in Edinburgh. First established as a radical political paper in 1817, it began daily publication in 1855 and remained a broadsheet until ...

'' called it a book to "keep a jaded reviewer out of bed in the small hours"; ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' said that the final twist "is really startling and ingenious, and though the reader is given a perfectly fair chance of guessing it none but the most ingenious can hope to do so"; and the reviewer in ''The Liverpool Echo

The ''Liverpool Echo'' is a newspaper published by Trinity Mirror North West & North Wales – a subsidiary company of Reach plc and is based in St. Paul's Square, Liverpool, England. It is published Monday through Sunday, and is Liverpool's da ...

'' called Sayers "the greatest of all detective story writers", though worried that her plots were so clever that some readers might struggle to keep up with them.

Over the following two years Sayers published two Wimsey novels (neither featuring Harriet Vane)—''Murder Must Advertise

''Murder Must Advertise'' is a 1933 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, the eighth in her series featuring Lord Peter Wimsey. Most of the action of the novel takes place in an advertising agency, a setting with which Sayers was familiar as s ...

'' (1933) and ''The Nine Tailors

''The Nine Tailors'' is a 1934 mystery novel by the British writer Dorothy L. Sayers, her ninth featuring Lord Peter Wimsey. The story is set in the Lincolnshire Fens, and revolves around a group of bell-ringers at the local parish church. The ...

'' (1934)—and a collection of short stories, ''Hangman's Holiday

''Hangman's Holiday'' is a collection of short stories, mostly murder mysteries, by Dorothy L. Sayers. This collection, the ninth in the Lord Peter Wimsey series, was first published by Gollancz in 1933, and has been reprinted a number of time ...

'', featuring not only the patrician Wimsey but also a proletarian salesman and solver of mysteries, Montague Egg

Montague Egg is a fictional amateur detective, who appears in eleven short stories by Dorothy L. Sayers.

Unlike Sayers's better-known creation, Lord Peter Wimsey, Egg does not actively pursue investigations. Usually, he is witness to the discovery ...

. She edited a third and final volume of ''Great Short Stories of Detection, Mystery and Horror'' and began reviewing crime novels for ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British Sunday newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of N ...

''. Her reviews covered works by most of her important contemporaries, including her fellow "Queens of Crime" of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction

The Golden Age of Detective Fiction was an era of classic murder mystery novels of similar patterns and styles, predominantly in the 1920s and 1930s. While the Golden Age proper is usually taken to refer to works from that period, this type of f ...

—Christie and Margery Allingham

Margery Louise Allingham (20 May 1904 – 30 June 1966) was an English novelist from the "Golden Age of Detective Fiction", and considered one of its four " Queens of Crime", alongside Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers and Ngaio Marsh.

All ...

. Kenney comments that much of Sayers's thinking on the mystery novel and literature generally can be gleaned from her reviews, which reveal much about her attitude to art. She expected authors to write excellent prose and to avoid situations and plot devices already used by other writers.

Sayers did not enjoy writing ''Murder Must Advertise'' and thought it an artistic failure:

Kenney describes the book as "flawed but brilliant". In terms of its literary status in relation to more manifestly serious fiction of Sayers's day, Kenney ranks it below the final three Wimsey novels, ''The Nine Tailors'', ''Gaudy Night

''Gaudy Night'' (1935) is a mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, the tenth featuring Lord Peter Wimsey, and the third including Harriet Vane.

The dons of Harriet Vane's ''alma mater'', the all-female Shrewsbury College, Oxford (based on Say ...

'' and ''Busman's Honeymoon

''Busman's Honeymoon'' is a 1937 novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, her eleventh and last featuring Lord Peter Wimsey, and her fourth and last to feature Harriet Vane.

Plot introduction

Lord Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane marry and go to spend the ...

''.

Like ''Murder Must Advertise'', ''The Nine Tailors'' draws on the author's personal experiences. Her portrait of the Rev Theodore Venables "tenderly evoked" her father, "unworldly, self-effacing ndlovable", as Reynolds puts it.Reynolds (1993), p. 207 The rectory in which Wimsey and his manservant, Bunter, are offered refuge after a car crash, resembles that in which Sayers grew up. With much of the storyline featuring bell-ringing, she spent considerable time researching campanology

Campanology (/kæmpəˈnɒlədʒi/) is both the scientific and artistic study of bells, encompassing their design, tuning, and the methods by which they are rung. It delves into the technology behind bell casting and tuning, as well as the rich ...

which gave her considerable trouble, and there were technical errors in her description of the practice. The book gained enthusiastic notices. In ''The News Chronicle

The ''News Chronicle'' was a British daily newspaper. Formed by the merger of '' The Daily News'' and the ''Daily Chronicle'' in 1930, it ceased publication on 17 October 1960,''Liberal Democrat News'' 15 October 2010, accessed 15 October 2010 be ...

'', Charles Williams (British writer), Charles Williams wrote that it was "not merely admirable; it is adorable. ... It is a great book". ''The Daily Herald'' said, "This is unquestionably Miss Sayers's best—until the next one".

Last novels and early religious works, 1935–1939