Domenico Brescia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

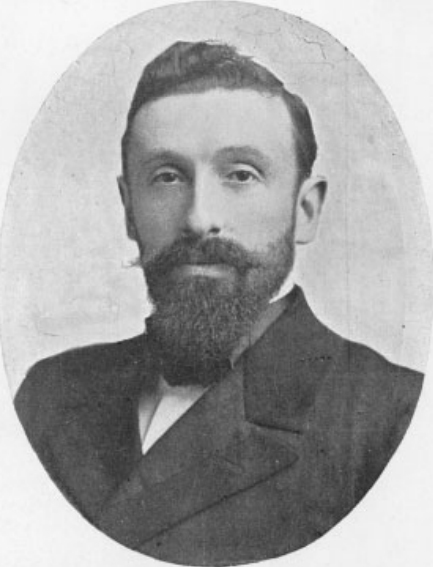

Domenico Brescia (28 April 1866–1939) was an

Domenico Brescia (28 April 1866–1939) was an

''Bringing the Masses to the Music: Ulderico Marcelli and the Silent Film in San Francisco''

Retrieved on June 30, 2009. Brescia led the

''Harvard Dictionary of Music''

Harvard University Press, 1969, p. 253. Brescia influenced two students who would later make names for themselves in Ecuadorian contemporary music: Segundo Luis Moreno and Luis H. Salgado. Marcelli left for

''Emma Brescia Gardner papers, 1898-1996''

. Retrieved on June 30, 2009. In 1926, Brescia worked with writer

In 1926, Brescia worked with writer

National music business magazine ''Musical America'' ran a full-page review by violinist and composer Victor Lichtenstein with photographs. Lichtenstein stated the play “was brilliantly presented in the

''The Coolidge Legacy''

Retrieved on June 30, 2009. *1931 - ''Ricercare (quasi Fantasia) e Fuga per Organo'' *1937 - ''String quartet no. 6'' (copyright June 15, 1937)Library of Congress, 1938

Catalog of Copyright Entries, p. 885.

Retrieved on June 30, 2009. *''Twelve Two Part Inventions for the Pianoforte in Retrograde Inverse Canon''

Domenico Brescia (28 April 1866–1939) was an

Domenico Brescia (28 April 1866–1939) was an Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and def ...

who taught in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

and Ecuador

Ecuador, officially the Republic of Ecuador, is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. It also includes the Galápagos Province which contain ...

, then became known in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

for writing chamber music as well as musical accompaniment for dramatic performances.Music Library Association, Northern California Chapter. MLA NCC Newsletter, Vol. 16, no. 2 (Spring 2002). John L. Walker''Bringing the Masses to the Music: Ulderico Marcelli and the Silent Film in San Francisco''

Retrieved on June 30, 2009. Brescia led the

Music Theory

Music theory is the study of theoretical frameworks for understanding the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory": The first is the "Elements of music, ...

department at Mills College

Mills College at Northeastern University in Oakland, California is part of Northeastern University's global university system. Mills College was founded as the Young Ladies Seminary in 1852 in Benicia, California; it was relocated to Oakland in ...

.

Brescia was born in Pirano

Piran (; ) is a town in southwestern Slovenia on the Gulf of Piran on the Adriatic Sea. It is one of the three major towns of Slovenian Istria. A bilingual city, with population speaking both Slovene and Italian, Piran is known for its medieva ...

, near Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

in 1866, at a time when the area was part of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

. After studying at the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna (, abbreviated Unibo) is a Public university, public research university in Bologna, Italy. Teaching began around 1088, with the university becoming organised as guilds of students () by the late 12th century. It is the ...

he became a member of the Royal Academy of Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

as well the Royal Academy of Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

.

Brescia went to Santiago, Chile

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile (), is the capital and largest city of Chile and one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is located in the country's central valley and is the center of the Santiago Metropolitan Regi ...

to teach harmony at the national conservatory, and eventually became the assistant director of the school. There, he met Ulderico Marcelli who was studying violin, brass and composition. In 1903, Brescia followed Marcelli to Quito

Quito (; ), officially San Francisco de Quito, is the capital city, capital and second-largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its metropolitan area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha Province, P ...

, Ecuador to become the director of the conservatory there, picking up some of sour-tempered Marcelli's unhappy students. Brescia was the first Western composer to utilize native Ecuadorean elements in his works, including the successful ''Sinfonia Ecuatoriana''.Apel, Willi''Harvard Dictionary of Music''

Harvard University Press, 1969, p. 253. Brescia influenced two students who would later make names for themselves in Ecuadorian contemporary music: Segundo Luis Moreno and Luis H. Salgado. Marcelli left for

San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

in 1910 and, due to Ecuador's increasing political unrest, Brescia left the country in 1911. By 1914, he had settled in San Francisco teaching voice and composing music.

In 1919, Brescia wrote the musical accompaniment to ''Life'', a Grove Play

The Grove Play is an annual theatrical production written, produced and performed by and for Bohemian Club members, and staged outdoors in California at the Bohemian Grove each summer.

In 1878, the Bohemian Club of San Francisco first took to th ...

performed at the Bohemian Grove

The Bohemian Grove is a restricted 2,700-acre (1,100-hectare) campground in Monte Rio, California. Founded in 1878, it belongs to a private gentlemen's club known as the Bohemian Club. In mid-July each year, the Bohemian Grove hosts a more than ...

. Ecuadorian Indian moods were used in two musical numbers. Brescia wrote in the notes to the score that he thought it was the first time that a chromatic

Diatonic and chromatic are terms in music theory that are used to characterize scales. The terms are also applied to musical instruments, intervals, chords, notes, musical styles, and kinds of harmony. They are very often used as a pair, es ...

set of cowbells

The cowbell is an idiophone hand percussion instrument used in various styles of music, such as Latin and rock. It is named after the similar bell used by herdsmen to keep track of the whereabouts of cows. The instrument initially and traditio ...

, spanning an octave and a half, had been used as a symphony instrument. Brescia brought Marcelli into the Bohemian Club

The Bohemian Club is a private club with two locations: a city clubhouse in the Nob Hill district of San Francisco, California, and the Bohemian Grove, a retreat north of the city in Sonoma County. Founded in 1872 from a regular meeting of jour ...

where Marcelli wrote the music for the next year's Grove Play.

In 1921, Brescia's ''Dithyrambic Suite'' for woodwind quintet premiered at Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge

Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge (October 30, 1864 – November 4, 1953), born Elizabeth Penn Sprague, was an American pianist and patron of music, especially of chamber music.

Biography

Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge's father was a wealthy wholesale ...

's Berkshire Chamber Music Festival, with the performance featuring flautist Georges Barrère

Georges Barrère (Bordeaux, October 31, 1876 - New York City, New York, June 14, 1944) was a French flutist.Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2001)

Early life

Georges Barrère was the son of a cabinetmaker, Gabriel Barrère, and Marie P ...

. Reviewer Carl H. Tollefsen commented on the name ''Dithyrambic'', writing "After hearing the music and in order to link my recollections of it with the title, I decided that the words 'Did he ramble' would bring back both. I'll say he did."

In 1925, Brescia moved to Oakland

Oakland is a city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area in the U.S. state of California. It is the county seat and most populous city in Alameda County, with a population of 440,646 in 2020. A major West Coast port, Oakland is ...

as professor of music composition at Mills College. He headed the music theory department as well.Emory Libraries''Emma Brescia Gardner papers, 1898-1996''

. Retrieved on June 30, 2009.

In 1926, Brescia worked with writer

In 1926, Brescia worked with writer George Sterling

George Sterling (December 1, 1869 – November 17, 1926) was an American writer based in the San Francisco, California Bay Area and Carmel-by-the-Sea. He was considered a prominent poet and playwright and proponent of Bohemianism during the fir ...

to compose the music for Sterling's Grove Play entitled ''Truth

Truth or verity is the Property (philosophy), property of being in accord with fact or reality.Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionarytruth, 2005 In everyday language, it is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise cor ...

''. Brescia's ''Truth'' score was one of his most highly-praised works. The ''Pacific Grove Musical Review'', a news magazine for the music business, reported: “Domenico Brescia, the distinguished pedagogue and composer, scored a great personal triumph at the Bohemian Grove on Saturday evening, July 31, when his grove play, ''Truth'', for which George Sterling

George Sterling (December 1, 1869 – November 17, 1926) was an American writer based in the San Francisco, California Bay Area and Carmel-by-the-Sea. He was considered a prominent poet and playwright and proponent of Bohemianism during the fir ...

has written an excellent book, was presented before a distinguished audience.”National music business magazine ''Musical America'' ran a full-page review by violinist and composer Victor Lichtenstein with photographs. Lichtenstein stated the play “was brilliantly presented in the

Bohemian Grove

The Bohemian Grove is a restricted 2,700-acre (1,100-hectare) campground in Monte Rio, California. Founded in 1878, it belongs to a private gentlemen's club known as the Bohemian Club. In mid-July each year, the Bohemian Grove hosts a more than ...

, Sonoma County, by members of the Club, assisted by the major portion of the San Francisco Symphony. … Domenico Brescia is the child of his age, and so we are not surprised to find in the musical interpretation of Mr. Sterling’s poem something of contemporary harmonic idiom and a subtle and ingenious use of modern orchestral color.” He continued:The lyric note of the music is struck in the interpretation of the characters of Egon, the poet, and Dendra, the shepherd girl, likewise in the charming ballet music which accompanies the feast at the king’s court. Music of an Oriental flavor, exquisitely poignant in character, has been assigned to the episode of Egon and Dendra. … A number of these interludes deserve to be popular. There is not a trivial bar in the entire score, in spite of the fluidity of the melodic line, sustained by vigorous rhythms and sometimes strange harmonic combinations. … A distinguished audience … expressed enthusiastic appreciation.In 1928, Mills completed a new music building which was dedicated with a premier performance of Brescia's suite for piano and woodwinds. Brescia brought with him the favor of Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, patron to modern chamber music, who subsequently subsidized various music department activities at Mills. Brescia held his professorship until his death in 1939. Brescia had one daughter, Emma (1902–1968), who was married to American poet

Robert Penn Warren

Robert Penn Warren (April 24, 1905 – September 15, 1989) was an American poet, novelist, literary critic and professor at Yale University. He was one of the founders of New Criticism. He was also a charter member of the Fellowship of Southern ...

during the period 1930–1951, then earned a Ph.D. from Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

in 1957 and began teaching foreign language at Mitchell College

Mitchell College is a private college in New London, Connecticut, United States. In fall 2020 it had an enrollment of 572 students and 68 faculty. Admission rate was 70%. The college offers associate and bachelor's degrees in fourteen subjects ...

in New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the outlet of the Thames River (Connecticut), Thames River in New London County, Connecticut, which empties into Long Island Sound. The cit ...

, in 1963.

Works

*1900s - ''Sinfonia Ecuatoriana'' *1919 - ''Life'', a Grove Play *1921 - ''Dithyrambic Suite'' for woodwind quintet *1922 - ''Second Suite for Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Horn, and Bassoon'' *1926 - '' Truth: A Grove Play'' *1928 - ''Suite for Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Horn, Bassoon and Piano''Library of Congress. Cyrilla Barr''The Coolidge Legacy''

Retrieved on June 30, 2009. *1931 - ''Ricercare (quasi Fantasia) e Fuga per Organo'' *1937 - ''String quartet no. 6'' (copyright June 15, 1937)Library of Congress, 1938

Catalog of Copyright Entries, p. 885.

Retrieved on June 30, 2009. *''Twelve Two Part Inventions for the Pianoforte in Retrograde Inverse Canon''

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Brescia, Domenico 1866 births 1939 deaths University of Bologna alumni Italian composers Italian male composers Italian emigrants Immigrants to the United States Emigrants from Austria-Hungary