Dil Pickle Club on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Dill Pickle Club (often spelled "Dil Pickle") was once a popular

As Jim Allege and others have documented, the Club played a pivotal role in the overlapping communities of queers and leftists during the Jazz Age, hosting panels such as "Do Perverts Menace Society?"--with Reitman and John Loughman arguing the negative.

As Jim Allege and others have documented, the Club played a pivotal role in the overlapping communities of queers and leftists during the Jazz Age, hosting panels such as "Do Perverts Menace Society?"--with Reitman and John Loughman arguing the negative.

Picture of Dil Pickle Club - Chicago Public Radio

{Dead link, date=May 2019 , bot=InternetArchiveBot , fix-attempted=yes

Dill Pickle Club Records

at

Images from the Dill Pickle Club

from the exhibitio

Chicago’s Dill Pickle Club: Where Anarchists Mixed With Doctors And Poets - Curious City

1915 establishments in Illinois Debating societies Dining clubs Freethought organizations Industrial Workers of the World in Illinois Literary circles Non-profit corporations Writing circles Speakeasies 1935 disestablishments in Illinois Non-profit organizations based in Chicago Cultural institutions and organizations in Chicago Underground organizations based in Chicago

Bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, originally practised by 19th–20th century European and American artists and writers.

* Bohemian style, a ...

club

Club may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Club'' (magazine)

* Club, a ''Yie Ar Kung-Fu'' character

* Clubs (suit), a suit of playing cards

* Club music

* "Club", by Kelsea Ballerini from the album ''kelsea''

Brands and enterprises

* ...

and countercultural hub located in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

. Operating primarily between 1917 and 1934, it served as a speakeasy

A speakeasy, also called a beer flat or blind pig or blind tiger, was an illicit establishment that sold alcoholic beverages. The term may also refer to a retro style bar that replicates aspects of historical speakeasies.

In the United State ...

, cabaret

Cabaret is a form of theatrical entertainment featuring music song, dance, recitation, or drama. The performance venue might be a pub, casino, hotel, restaurant, or nightclub with a stage for performances. The audience, often dining or drinking, ...

, theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors to present experiences of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The performers may communi ...

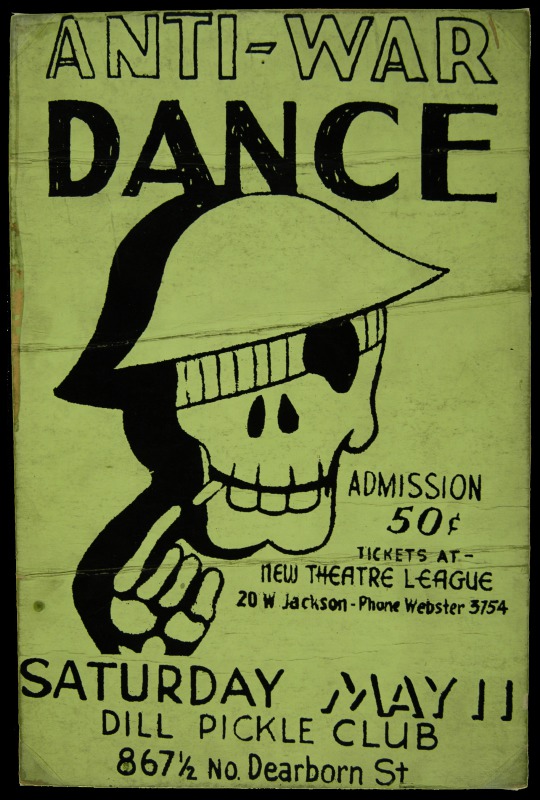

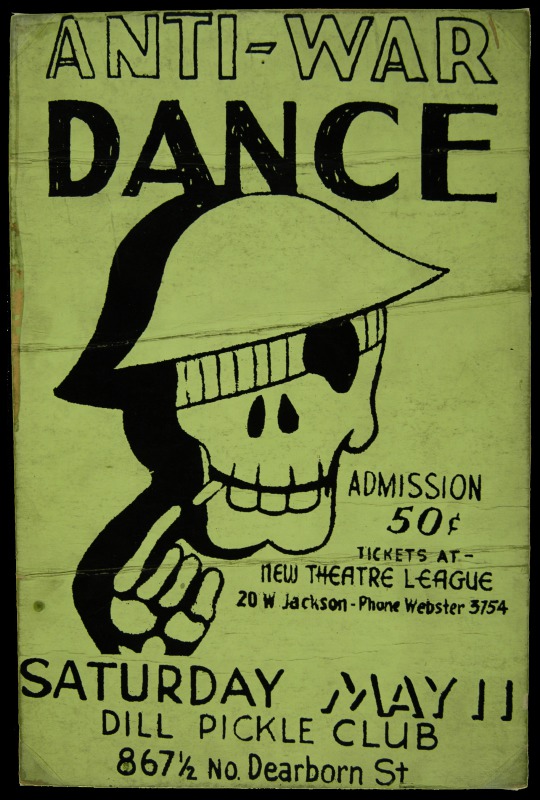

, radical forum, and intellectual salon during the Chicago Renaissance. Founded by former Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organizer John "Jack" Jones, the club became a legendary sanctuary for artists, anarchists, hoboes, queers, scientists, poets, sex radicals, and the intellectually curious of all backgrounds. Its blend of avant-garde experimentation, open debate, and irreverent humor marked it as one of the most influential cultural institutions in American history.

The club's legacy has seen several reincarnations, including Chicago Dil Pickle Club, the Dill Pickle Food Co-op, Dil Pickle Press, and the Dill Pickle Club of Portland, OR.

History

Founding and Early Years

The Dill Pickle Club grew out of radical discussion forums held at the Radical Bookshop on North Clark Street, operated by Howard and Lillian Udel. In 1914, John "Jack" Jones, a Canadian-born IWW organizer and soapbox speaker at nearby Washington Square Park (known colloquially as Bughouse Square), sought a larger space to accommodate the growing audience. He converted a barn at 18 Tooker Place into a meeting hall, and in 1917, formally incorporated the Dill Pickle Artisan's under Illinois nonprofit law to promote "arts, crafts, literature, and science." Jones was soon joined by two key collaborators:Jim Larkin

James Larkin (28 January 1874 – 30 January 1947), sometimes known as Jim Larkin or Big Jim, was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. He was one of the founders of the Irish Labour Party along with James Connolly and Willia ...

, an Irish labor organizer, and Dr. Ben Reitman

__NOTOC__

Ben Lewis Reitman M.D. (1879–1943) was an American anarchist and physician to the poor ("the hobo doctor"). He is best remembered today as one of radical Emma Goldman's lovers. Martin Scorsese's 1972 feature film ''Boxcar Bertha'' is ...

, an anarchist physician, birth control advocate, and former manager of Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

's speaking tours. Reitman's promotional acumen helped bring media attention to the club, making it a household name among radicals and intellectuals across the country.

Architecture and Atmosphere

Tucked into a narrow alley between Dearborn and State Streets, the entrance to the Dill Pickle Club was intentionally theatrical. The entrance was marked by a "DANGER" sign that which pointed to the orange main door which was lit by a green light. On the door, it read: "Step High, Stoop Low and Leave Your Dignity Outside." Once inside, another sign read "This club is established to elevate the minds of people to a lower level." Inside, the walls were adorned with murals, absurdist signage, poems, caricatures, and theatrical sets. The club featured a tearoom, a lending library, an art gallery, a cafe, and a lecture hall and ballroom with standing room for up to 700 guests.Activities and Events

Lectures and Debates

The Club's central function was to foster unfiltered discussion on taboo and progressive topics. Lectures bore cheeky titles such as "Should the Brownian movement Be Approached from the Rear?" Topics ranged from socialism, free love, atheism, and psychoanalysis to the birth control, venereal disease, and homosexuality. Speakers included figures likeEugene Debs

Eugene Victor Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five-time candidate of the Socialist Party o ...

, Emma Goldman, Big Bill Haywood

William Dudley Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928), nicknamed "Big Bill", was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socia ...

, Aimee Semple McPherson

Aimee Elizabeth Semple McPherson (née Kennedy; October 9, 1890 – September 27, 1944), also known as Sister Aimee or Sister, was a Canadian-born American Pentecostalism, Pentecostal Evangelism, evangelist and media celebrity in the 1920 ...

, Magnus Hirschfeld

Magnus Hirschfeld (14 May 1868 – 14 May 1935) was a German physician, Sexology, sexologist and LGBTQ advocate, whose German citizenship was later revoked by the Nazi government.David A. Gerstner, ''Routledge International Encyclopedia of Queer ...

, and Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the 19th century for high-profile representations of trade union causes, and in the 20th century for several criminal matters, including the ...

. At one debate, Ben Hecht

Ben Hecht (; February 28, 1894 – April 18, 1964) was an American screenwriter, director, producer, playwright, journalist, and novelist. A journalist in his youth, he went on to write 35 books and some of the most enjoyed screenplays and play ...

proposed: "Resolved: That People Who Attend Literary Debates are Imbeciles," and won by simply pointing to the audience and resting his case. Another time, a German homosexual speaker drew a crowd of over 300--at a time when same-sex relations were criminalized nationwide.

Reitman himself often gave provocative talks such as "Satisfying Sex Needs Without Trouble" or "Favorite Methods of Suicide," drawing both applause and outrage.

Theatrical and Artistic Programs

The Dill Pickle Players, the Club's resident troupe, staged operas, jazz dances, poetry readings and one-act plays including works byIbsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright, poet and actor. Ibsen is considered the world's pre-eminent dramatist of the 19th century and is often referred to as "the father of modern drama." He pioneered ...

, Shaw

Shaw may refer to:

Places Australia

*Shaw, Queensland

Canada

*Shaw Street, a street in Toronto

England

*Shaw, Berkshire, a village

*Shaw, Greater Manchester, a location in the parish of Shaw and Crompton

* Shaw, Swindon, a suburb of Swindon

** ...

, O'Neil, and Yeats

William Butler Yeats (, 13 June 186528 January 1939), popularly known as W. B. Yeats, was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer, and literary critic who was one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the ...

, alongside local and original works. Performers ranged from university professors to strippers. One production featured actress Angela D'Amore playing Miss Julie

''Miss Julie'' () is a naturalistic play written in 1888 by August Strindberg. It is set on Midsummer's Eve and the following morning, which is Midsummer and the Feast Day of St. John the Baptist. The setting is an estate of a count in Sweden. ...

; anther staged Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an List of poets from the United States, American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Ita ...

's translations of Japanese Noh plays.

Visual artists like Edgar Miller designed sets and flyers. Sunday poetry readings featured Carl Sandburg

Carl August Sandburg (January 6, 1878 – July 22, 1967) was an American poet, biographer, journalist, and editor. He won three Pulitzer Prizes: two for his poetry and one for his biography of Abraham Lincoln. During his lifetime, Sandburg w ...

, Robert Frost

Robert Lee Frost (March26, 1874January29, 1963) was an American poet. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American Colloquialism, colloquial speech, Frost frequently wrote about settings from rural life in New E ...

, Vachel Lindsay

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (; November 10, 1879 – December 5, 1931) was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern ''singing poetry,'' as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted.

Early years

Lindsay was born ...

, and others. Sandburg listed the Dill Pickle as his school on a payroll form, and Sherwood Anderson praised it as a place where "streetcar conductors sat beside professors."

Social and Queer Life

The Club was an important site for Chicago's early LGBT+ community. It hosted lectures on "The Third Sex" and talks by queer figures like Jack Ryan and Magnus Hirschfeld. Cross-dressing and masquerade balls were common, and the Pickle was noted for tolerating and welcoming homosexuality, even as mainstream society criminalized it. The atmosphere allowed expressions of gender and sexuality rare accepted elsewhere in public. As Jim Allege and others have documented, the Club played a pivotal role in the overlapping communities of queers and leftists during the Jazz Age, hosting panels such as "Do Perverts Menace Society?"--with Reitman and John Loughman arguing the negative.

As Jim Allege and others have documented, the Club played a pivotal role in the overlapping communities of queers and leftists during the Jazz Age, hosting panels such as "Do Perverts Menace Society?"--with Reitman and John Loughman arguing the negative.

Satire and Scandal

The Club's irreverence knew few bounds. One heckler interrupted an anti-smoking talk by saying the speaker's face alone made him want to start smoking. Another event, planned around a pregnant woman debating her options--abortion, adoption, or suicide--erupted into a riot of thrown eggs and vegetables. Even some regulars declared it a step too far.Decline and Closure

By the late 1920s, many of the club's original literary figures had left for New York or Hollywood. At the same time, mob interests pressured Jones to allow bootlegging, and when he refused, authorities cracked down. In 1931, Jones was arrested for selling alcohol during Prohibition. After accumulating 150 citations in a single winter, the club was shuttered in 1933 under a rarely-enforced stature barring dance halls near churches. Attempts to reopen the club in 1944 failed when the building was condemned. Jones died in poverty in 1940.Legacy

Despite its chaotic demise, the Dill Pickle Club remains one of Chicago's most storied artistic and intellectual institutions. Chicago Magazine listed it among the city's 40 greatest artistic breakthroughs. According toFranklin Rosemont

Franklin Rosemont (1943–2009) was an American poet, artist, historian, street speaker, and co-founder of the Chicago Surrealist Group. Over four decades, Franklin produced a body of work, of declarations, manifestos, poetry, collage, hidden hi ...

, it was "far and away the best-loved, most notorious, most stimulating, and most influential little gathering place in the city's history."

The club inspired later forums such as the College of Complexes and has been revived in name by modern arts organizations across the country. In recent years, historians have reassessed the club's significants in both LGBTQ+ and labor history, underscoring its role in advancing dissident discourse during an era of repression.

Today, nothing remains of the original Tooker Place barn but a parking garage.

Popular attendees

The club was frequented by many radical American activists, political speakers and authors. It was accepting of homosexuals. Among the American activists and speakers wasClarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the 19th century for high-profile representations of trade union causes, and in the 20th century for several criminal matters, including the ...

, Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

, Big Bill Haywood

William Dudley Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928), nicknamed "Big Bill", was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socia ...

, Hippolyte Havel

Hippolyte Havel (August 11, 1871 – March 10, 1950) was an American anarchist who was known as an activist in the United States and part of the radical circle around Emma Goldman in the early 20th century. He had been imprisoned as a young ma ...

, Lucy Parsons

Lucy E. Parsons ( – March 7, 1942) was a US social anarchist and later anarcho-communist, well-known throughout her long life for her fiery speeches and writings. She was a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World. There are d ...

, Ben Reitman

__NOTOC__

Ben Lewis Reitman M.D. (1879–1943) was an American anarchist and physician to the poor ("the hobo doctor"). He is best remembered today as one of radical Emma Goldman's lovers. Martin Scorsese's 1972 feature film ''Boxcar Bertha'' is ...

and Nina Spies. American authors included Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

winner Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American author, muckraker journalist, and political activist, and the 1934 California gubernatorial election, 1934 Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

along with Sherwood Anderson

Sherwood Anderson (September 13, 1876 – March 8, 1941) was an American novelist and short story writer, known for subjective and self-revealing works. Self-educated, he rose to become a successful copywriter and business owner in Cleveland and ...

, Carl Sandburg

Carl August Sandburg (January 6, 1878 – July 22, 1967) was an American poet, biographer, journalist, and editor. He won three Pulitzer Prizes: two for his poetry and one for his biography of Abraham Lincoln. During his lifetime, Sandburg w ...

, Ben Hecht

Ben Hecht (; February 28, 1894 – April 18, 1964) was an American screenwriter, director, producer, playwright, journalist, and novelist. A journalist in his youth, he went on to write 35 books and some of the most enjoyed screenplays and play ...

, Arthur Desmond, Vachel Lindsay

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (; November 10, 1879 – December 5, 1931) was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern ''singing poetry,'' as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted.

Early years

Lindsay was born ...

, Djuna Barnes

Djuna Barnes ( ; June 12, 1892 – June 18, 1982) was an American artist, illustrator, journalist, and writer who is perhaps best known for her novel '' Nightwood'' (1936), a cult classic of lesbian fiction and an important work of modernist lite ...

, William Carlos Williams

William Carlos Williams (September 17, 1883 – March 4, 1963) was an American poet and physician closely associated with modernism and imagism. His '' Spring and All'' (1923) was written in the wake of T. S. Eliot's '' The Waste Land'' (1922). ...

, Kenneth Rexroth

Kenneth Charles Marion Rexroth (December 22, 1905 – June 6, 1982) was an American poet, translator, and critical essayist. He is regarded as a central figure in the San Francisco Renaissance, and paved the groundwork for the movement. Althoug ...

and Vincent Starrett

Charles Vincent Emerson Starrett (; October 26, 1886 – January 5, 1974), known as Vincent Starrett, was a Canadian-born American writer, newspaperman, and bibliophile.

Biography

Charles Vincent Emerson Starrett was born above his grandfathe ...

. Other common attendees were poet, writer and Wobbly, Slim Brundage

Myron Reed "Slim" Brundage (November 29, 1903 – October 18, 1990) was the "founder and janitor" of the College of Complexes, a radical social center in Chicago during the 1950s. It was known as Chicago's Number One "beatnik bistro".

Biography

...

, speaker Martha Biegler, speaker Elizabeth Davis, artist Stanislav Szukalski Stanislav and variants may refer to:

People

*Stanislav (given name), a Slavic given name with many spelling variations (Stanislaus, Stanislas, Stanisław, etc.)

Places

* Stanislav, Kherson Oblast, a coastal village in Ukraine

* Stanislaus County, ...

, Harry Wilson and egoist F. M. Wilkesbarr (aka Malfew Seklew).

A club for people with ideas and questions, it often attracted a mixed crowd. Scientist

A scientist is a person who Scientific method, researches to advance knowledge in an Branches of science, area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engag ...

s, panhandler

Begging (also known in North America as panhandling) is the practice of imploring others to grant a favor, often a gift of money, with little or no expectation of reciprocation. A person doing such is called a beggar or panhandler. Beggars m ...

s, prostitute

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-pe ...

s, socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

s, anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

s, con men

A scam, or a confidence trick, is an attempt to defraud a person or group after first gaining their trust. Confidence tricks exploit victims using a combination of the victim's credulity, naivety, compassion, vanity, confidence, irresponsibili ...

, tax advocates, religious zealots, social worker

Social work is an academic discipline and practice-based profession concerned with meeting the basic needs of individuals, families, groups, communities, and society as a whole to enhance their individual and collective well-being. Social wo ...

s and hobo

A hobo is a migrant worker in the United States. Hoboes, tramps, and bums are generally regarded as related, but distinct: a hobo travels and is willing to work; a tramp travels, but avoids work if possible; a bum neither travels nor works.

Et ...

es were commonly at the club. Chicagoan George Wellington "Cap" Streeter was also said to have visited and spoken at the Dil Pickle Club.

In literature

The Dill Pickle Club features prominently in the play Dear Rhoda by Donna Russell and David Ranney.Dear Rhoda—”A Play in Two Acts, by Donna Russell and David Ranney.”, www.newberry.org/calendar/dear-rhoda. Accessed 28 Oct. 2024.Notes

*Original Dill Pickle Club address: 10 Tooker Place, Chicago, IllinoisReferences

External links

Picture of Dil Pickle Club - Chicago Public Radio

{Dead link, date=May 2019 , bot=InternetArchiveBot , fix-attempted=yes

Dill Pickle Club Records

at

the Newberry Library

The Newberry Library is an independent research library, specializing in the humanities. It is located in Chicago, Illinois, and has been free and open to the public since 1887. The Newberry's mission is to foster a deeper understanding of our wor ...

Images from the Dill Pickle Club

from the exhibitio

Chicago’s Dill Pickle Club: Where Anarchists Mixed With Doctors And Poets - Curious City

1915 establishments in Illinois Debating societies Dining clubs Freethought organizations Industrial Workers of the World in Illinois Literary circles Non-profit corporations Writing circles Speakeasies 1935 disestablishments in Illinois Non-profit organizations based in Chicago Cultural institutions and organizations in Chicago Underground organizations based in Chicago