Dies Committee on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative

The Overman Committee was a subcommittee of the

The Overman Committee was a subcommittee of the

On May 26, 1938, the House Committee on Un-American Activities was established as a special investigating committee, reorganized from its previous incarnations as the Fish Committee and the McCormack–Dickstein Committee, to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having communist or fascist ties; however, it concentrated its efforts on communists. It was chaired by Martin Dies Jr. (D-Tex.), and therefore known as the Dies Committee. Its records are held by the

On May 26, 1938, the House Committee on Un-American Activities was established as a special investigating committee, reorganized from its previous incarnations as the Fish Committee and the McCormack–Dickstein Committee, to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having communist or fascist ties; however, it concentrated its efforts on communists. It was chaired by Martin Dies Jr. (D-Tex.), and therefore known as the Dies Committee. Its records are held by the

The House Committee on Un-American Activities became a standing (permanent) committee on January 3, 1945. Democratic Representative Edward J. Hart of New Jersey became the committee's first chairman. Under the mandate of Public Law 600, passed by the

The House Committee on Un-American Activities became a standing (permanent) committee on January 3, 1945. Democratic Representative Edward J. Hart of New Jersey became the committee's first chairman. Under the mandate of Public Law 600, passed by the

On July 31, 1948, the committee heard testimony from Elizabeth Bentley, an American who had been working as a Soviet agent in

On July 31, 1948, the committee heard testimony from Elizabeth Bentley, an American who had been working as a Soviet agent in

Following the censure of Joseph McCarthy (who never served in the House, nor on HUAC; he was a U.S. Senator), the prestige of HUAC began a gradual decline in the late 1950s. By 1959, the committee was being denounced by former President

Following the censure of Joseph McCarthy (who never served in the House, nor on HUAC; he was a U.S. Senator), the prestige of HUAC began a gradual decline in the late 1950s. By 1959, the committee was being denounced by former President

''Records of the US House of Representatives, Record Group 233: Records of the House Un-American Activities Committee, 1945–1969 (Renamed the) House Internal Security Committee, 1969–1976.''

Washington, DC: Center for Legislative Archives, National Archives and Records, July 1995; p. 4. The committee's files and staff were transferred on that day to the House Judiciary Committee.

Investigation of un-American propaganda activities in the United States. Hearings before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives (1938–1944), Volumes 1–17 with Appendices.

University of Pennsylvania online gateway to Internet Archive and Hathi Trust.

United States House Committee on Internal Security

University of Pennsylvania online gateway to Internet Archive and Hathi Trust. * Schamel, Gharles E. Inventory of records of the Special Committee on Un-American activities, 1938–1944 (the Dies committee). Center for Legislative Archives,

''Records of the House Un-American Activities committee, 1945–1969, renamed the House Internal Security committee, 1969–1976.''

Center for Legislative Archives, National Archives and Records Administration. Washington, D.C., July 1995. *

*

History.House.gov

HUAC – permanent standing House Committee on Un-American Activities

History.House.gov

HUAC – 1948 Alger Hiss-Whittaker Chambers hearing before HUAC

Eastern Carolina University Libraries

The Cold War and Internal Security Collection (CWIS): HUAC

The Spartacus Educational website, UK * House Unamerican Activities Committee (HUAC) Collection: Pamphlets collected by HUAC, many of which the committee deemed "un-American". (4,000 pamphlets). From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

{{Authority control 1938 establishments in Washington, D.C. 1975 disestablishments in Washington, D.C. Anti-communist organizations in the United States Anti-fascist organizations in the United States Cold War history of the United States Un-American activities Government agencies established in 1938 McCarthyism Political repression in the United States

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly or other form of organization. A committee may not itself be considered to be a form of assembly or a decision-making body. Usually, an assembly o ...

of the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

ties. It became a standing (permanent) committee in 1946, and from 1969 onwards it was known as the House Committee on Internal Security. When the House abolished the committee in 1975, its functions were transferred to the House Judiciary Committee

The U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary, also called the House Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of the United States House of Representatives. It is charged with overseeing the administration of justice within the federal courts, f ...

.

The committee's anti-communist investigations are often associated with McCarthyism

McCarthyism is a political practice defined by the political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals and a Fear mongering, campaign spreading fear of communist and Soviet influence on American institutions and of Soviet espionage i ...

, although Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

himself (as a U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

) had no direct involvement with the House committee. McCarthy was the chairman of the Government Operations Committee and its Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

The Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (PSI), stood up in March 1941 as the "Truman Committee," is the oldest subcommittee of the United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs (formerly the Committee on Govern ...

of the U.S. Senate, not the House.

History

Precursors to the committee

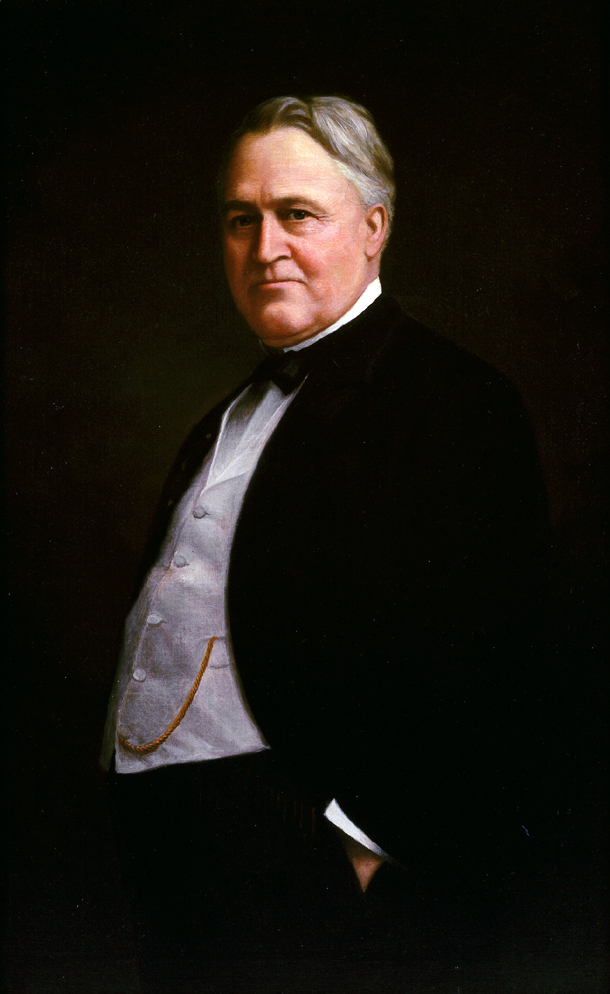

Overman Committee (1918–1919)

The Overman Committee was a subcommittee of the

The Overman Committee was a subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally known as the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a Standing committee (United States Congress), standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the United States Departm ...

chaired by North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

Democratic Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

Lee Slater Overman that operated from September 1918 to June 1919. The subcommittee investigated German as well as "Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

elements" in the United States.Schmidt, p. 136

This subcommittee was initially concerned with investigating pro-German sentiments in the American liquor industry. After World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

ended in November 1918, and the German threat lessened, the subcommittee began investigating Bolshevism, which had appeared as a threat during the First Red Scare

The first Red Scare was a period during History of the United States (1918–1945), the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of Far-left politics, far-left movements, including Bolsheviks, Bolshevism a ...

after the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

in 1917. The subcommittee's hearing into Bolshevik propaganda, conducted from February 11 to March 10, 1919, played a decisive role in constructing an image of a radical threat to the United States during the first Red Scare.Schmidt, p. 144

Fish Committee (1930)

U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

Hamilton Fish III (R-NY), who was a fervent anti-communist, introduced, on May 5, 1930, House Resolution 180, which proposed to establish a committee to investigate communist activities in the United States. The resulting committee, Special Committee to Investigate Communist Activities in the United States commonly known as the Fish Committee, undertook extensive investigations of people and organizations suspected of being involved with or supporting communist activities in the United States. Among the committee's targets were the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is an American nonprofit civil rights organization founded in 1920. ACLU affiliates are active in all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. The budget of the ACLU in 2024 was $383 million.

T ...

and communist presidential candidate William Z. Foster. The committee recommended granting the United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a United States federal executive departments, federal executive department of the U.S. government that oversees the domestic enforcement of Law of the Unite ...

more authority to investigate communists, and strengthening immigration and deportation laws to keep communists out of the United States.

McCormack–Dickstein Committee (1934–1937)

From 1934 to 1937, the committee, now named the Special Committee on Un-American Activities Authorized to Investigate Nazi Propaganda and Certain Other Propaganda Activities, chaired byJohn William McCormack

John William McCormack (December 21, 1891 – November 22, 1980) was an American politician from Boston, Massachusetts. McCormack served in the United States Army during World War I, and afterwards in the Massachusetts State Senate before winnin ...

( D- Mass.) and Samuel Dickstein

Samuel Dickstein (February 5, 1885 – April 22, 1954) was a Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Congressional Representative from New York (state), New York (22-year tenure), a New York State Supreme Court Justice, and a Soviet Union, ...

(D-NY), held public and private hearings and collected testimony filling 4,300 pages. The Special Committee was widely known as the McCormack–Dickstein committee. Its mandate was to get "information on how foreign subversive propaganda entered the U.S. and the organizations that were spreading it." Its records are held by the National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an independent agency of the United States government within the executive branch, charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It is also task ...

as records related to HUAC.

In 1934, the Special Committee subpoenaed most of the leaders of the fascist movement in the United States. Beginning in November 1934, the committee investigated allegations of a fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

plot to seize the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

, known as the "Business Plot

The Business Plot, also called the Wall Street Putsch and the White House Putsch, was a political conspiracy in 1933 in the United States to overthrow the government of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and install Smedley Butler as dictator. But ...

". Contemporary newspapers widely reported the plot as a hoax. While historians have questioned whether a coup was actually close to execution, most agree that some sort of "wild scheme" was contemplated and discussed.

It has been reported that while Dickstein served on this committee and the subsequent Special Investigation Committee, he was paid $1,250 a month by the Soviet NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

, which hoped to get secret congressional information on anti-communists and pro-fascists. A 1939 NKVD report stated Dickstein handed over "materials on the war budget for 1940, records of conferences of the budget sub commission, reports of the war minister, chief of staff and etc." However the NKVD was dissatisfied with the amount of information provided by Dickstein, after he was not appointed to HUAC to "carry out measures planned by us together with him." Dickstein unsuccessfully attempted to expedite the deportation of Soviet defector Walter Krivitsky

Walter Germanovich Krivitsky (Ва́льтер Ге́рманович Криви́цкий; birth name ''Samuel Gershevich Ginsberg,'' Самуил Гершевич Гинзберг, June 28, 1899 – February 10, 1941) was a Soviet military i ...

, while the Dies Committee kept him in the country. Dickstein stopped receiving NKVD payments in February 1940.

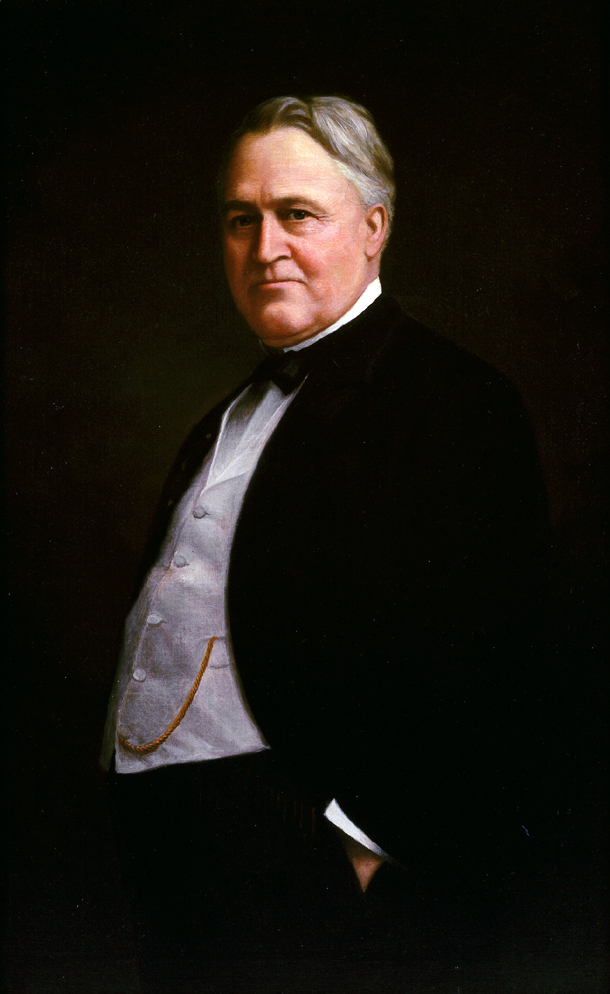

Dies Committee (1938–1944)

On May 26, 1938, the House Committee on Un-American Activities was established as a special investigating committee, reorganized from its previous incarnations as the Fish Committee and the McCormack–Dickstein Committee, to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having communist or fascist ties; however, it concentrated its efforts on communists. It was chaired by Martin Dies Jr. (D-Tex.), and therefore known as the Dies Committee. Its records are held by the

On May 26, 1938, the House Committee on Un-American Activities was established as a special investigating committee, reorganized from its previous incarnations as the Fish Committee and the McCormack–Dickstein Committee, to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having communist or fascist ties; however, it concentrated its efforts on communists. It was chaired by Martin Dies Jr. (D-Tex.), and therefore known as the Dies Committee. Its records are held by the National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an independent agency of the United States government within the executive branch, charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It is also task ...

as records related to HUAC.

In 1938, Hallie Flanagan

Hallie Flanagan Davis (August 27, 1889 – June 23, 1969) was an American theatrical producer and director, playwright, and author, best known as director of the Federal Theatre Project, a part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

B ...

, the head of the Federal Theatre Project

The Federal Theatre Project (FTP; 1935–1939) was a theatre program established during the Great Depression as part of the New Deal to fund live artistic performances and entertainment programs in the United States. It was one of five Federal ...

, was subpoenaed to appear before the committee to answer the charge the project was overrun with communists. Flanagan was called to testify for only a part of one day, while an administrative clerk from the project was called in for two entire days. It was during this investigation that one of the committee members, Joe Starnes (D-Ala.), famously asked Flanagan whether the English Elizabethan era

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The Roman symbol of Britannia (a female ...

playwright Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe ( ; Baptism, baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), also known as Kit Marlowe, was an English playwright, poet, and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the English Renaissance theatre, Eli ...

was a member of the Communist Party, and mused that ancient Greek tragedian " Mr. Euripides" preached class warfare.

In 1939, the committee investigated people involved with pro-Nazi organizations such as Oscar C. Pfaus and George Van Horn Moseley. Moseley testified before the committee for five hours about a "Jewish Communist conspiracy" to take control of the U.S. government. Moseley was supported by Donald Shea of the American Gentile League, whose statement was deleted from the public record as the committee found it so objectionable.

The committee also put together an argument for the internment of Japanese Americans

United States home front during World War II, During World War II, the United States forcibly relocated and Internment, incarcerated about 120,000 people of Japanese Americans, Japanese descent in ten #Terminology debate, concentration camps opera ...

known as the "Yellow Report". Organized in response to rumors of Japanese Americans being coddled by the War Relocation Authority

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was t ...

(WRA) and news that some former inmates would be allowed to leave camp and Nisei

is a Japanese language, Japanese-language term used in countries in North America and South America to specify the nikkeijin, ethnically Japanese children born in the new country to Japanese-born immigrants, or . The , or Second generation imm ...

soldiers to return to the West Coast, the committee investigated charges of fifth column

A fifth column is a group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. The activities of a fifth column can be overt or clandestine. Forces gathered in secret can mobilize ...

activity in the camps. A number of anti-WRA arguments were presented in subsequent hearings, but Director Dillon Myer debunked the more inflammatory claims. The investigation was presented to the 77th Congress, and alleged that certain cultural traits – Japanese loyalty to the Emperor, the number of Japanese fishermen in the US, and the Buddhist faith – were evidence for Japanese espionage. With the exception of Rep. Herman Eberharter (D-Pa.), the members of the committee seemed to support internment, and its recommendations to expedite the impending segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of human ...

of "troublemakers", establish a system to investigate applicants for leave clearance, and step up Americanization and assimilation efforts largely coincided with WRA goals.

Standing Committee (1945–1975)

The House Committee on Un-American Activities became a standing (permanent) committee on January 3, 1945. Democratic Representative Edward J. Hart of New Jersey became the committee's first chairman. Under the mandate of Public Law 600, passed by the

The House Committee on Un-American Activities became a standing (permanent) committee on January 3, 1945. Democratic Representative Edward J. Hart of New Jersey became the committee's first chairman. Under the mandate of Public Law 600, passed by the 79th Congress

The 79th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from January 3, 19 ...

, the committee of nine representatives investigated suspected threats of subversion or propaganda that attacked "the form of government as guaranteed by our Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

".

Under this mandate, the committee focused its investigations on real and suspected communists in positions of actual or supposed influence in the United States society. A significant step for HUAC was its investigation of the charges of espionage brought against Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official who was accused of espionage in 1948 for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. The statute of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjur ...

in 1948. This investigation ultimately resulted in Hiss's trial and conviction for perjury, and convinced many of the usefulness of congressional committees for uncovering communist subversion.

The chief investigator was Robert E. Stripling, senior investigator Louis J. Russell, and investigators Alvin Williams Stokes, Courtney E. Owens, and Donald T. Appell. The director of research was Benjamin Mandel.

In 1946, the committee considered opening investigations into the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

, but decided against doing so, prompting white supremacist committee member John E. Rankin (D-Miss.) to remark, "After all, the KKK is an old American institution." Twenty years later, in 1965–1966, however, the committee did conduct an investigation into Klan activities under chairman Edwin Willis (D-La.).

Hollywood Blacklist

In 1947, the committee held nine days of hearings into alleged communist propaganda and influence in theHollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood ...

motion picture industry. After conviction on contempt of Congress charges for refusal to answer some questions posed by committee members, " The Hollywood Ten" were blacklisted

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list; if people are on a blacklist, then they are considere ...

by the industry. Eventually, more than 300 artists – including directors, radio commentators, actors, and particularly screenwriters – were boycotted by the studios. Some, like Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is considered o ...

, Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American director, actor, writer, producer, and magician who is remembered for his innovative work in film, radio, and theatre. He is among the greatest and most influential film ...

, Alan Lomax

Alan Lomax (; January 31, 1915 – July 19, 2002) was an American ethnomusicologist, best known for his numerous field recordings of folk music during the 20th century. He was a musician, folklorist, archivist, writer, scholar, political activ ...

, Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for h ...

, and Yip Harburg

Edgar Yipsel Harburg (born Isidore Hochberg; April 8, 1896 – March 5, 1981) was an American popular song lyricist and librettist who worked with many well-known composers. He wrote the lyrics to the standards " Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?" (w ...

, left the U.S. or went underground to find work. Others like Dalton Trumbo

James Dalton Trumbo (December 9, 1905 – September 10, 1976) was an American screenwriter who scripted many award-winning films, including ''Roman Holiday'' (1953), '' Exodus'', ''Spartacus'' (both 1960), and '' Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo'' (194 ...

wrote under pseudonyms

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true meaning (orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individual's ow ...

or the names of colleagues. Only about ten percent succeeded in rebuilding careers within the entertainment industry.

In 1947, studio executives told the committee that wartime films—such as ''Mission to Moscow

Mission (from Latin 'the act of sending out'), Missions or The Mission may refer to:

Geography Australia

*Mission River (Queensland)

Canada

* Mission, British Columbia, a district municipality

* Mission, Calgary, Alberta, a neighbourhood

* ...

'', '' The North Star'', and '' Song of Russia''—could be considered pro-Soviet propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

, but claimed that the films were valuable in the context of the Allied war effort, and that they were made (in the case of ''Mission to Moscow'') at the request of White House officials. In response to the House investigations, most studios produced a number of anti-communist and anti-Soviet propaganda films such as '' The Red Menace'' (August 1949), '' The Red Danube'' (October 1949), '' The Woman on Pier 13'' (October 1949), '' Guilty of Treason'' (May 1950, about the ordeal and trial of Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal most commonly refers to

* Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of three species in the family Cardinalidae

***Northern cardinal, ''Cardinalis cardinalis'', the common cardinal of ...

József Mindszenty), '' I Was a Communist for the FBI'' (May 1951, Academy Award nominated for best documentary 1951, also serialized for radio), '' Red Planet Mars'' (May 1952), and John Wayne

Marion Robert Morrison (May 26, 1907 – June 11, 1979), known professionally as John Wayne, was an American actor. Nicknamed "Duke", he became a Pop icon, popular icon through his starring roles in films which were produced during Hollywood' ...

's ''Big Jim McLain

''Big Jim McLain'' is a 1952 American film noir political thriller film starring John Wayne and James Arness as HUAC investigators hunting down communists in the postwar Hawaii organized-labor scene. Edward Ludwig directed.

This was the first ...

'' (August 1952). Universal-International Pictures

Universal City Studios LLC, doing business as Universal Pictures (also known as Universal Studios or simply Universal), is an American film production and distribution company headquartered at the Universal Studios complex in Universal City, ...

was the only major studio that did not purposefully produce such a film.

The committee conducted many investigations into the Hollywood film industry. Some people within the industry gave names of people who were allegedly communists to HUAC. In total, 43 people were summoned to testify in front of the Washington hearing. Out of those subpoenaed, only 10 refused to testify, and they were cited for contempt in front of Congress. Those 10 ended up being sentenced; one of them being Albert Maltz

Albert Maltz (; October 28, 1908 – April 26, 1985) was an American playwright, fiction writer and screenwriter. He was one of the Hollywood Ten who were jailed in 1950 for their 1947 refusal to testify before the US Congress about their involv ...

. Maltz had parents who were Russian immigrants, leading people to believe he was a communist. Once his name was on the Blacklist, he refused to testify in front of the Washington hearings in October. He was then convicted and was sentenced with nine other people. The other nine people included Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole

Lester Cole (June 19, 1904 – August 15, 1985) was an American screenwriter. He was one of the Hollywood Ten, a group of screenwriters and directors who were cited for contempt of Congress and blacklisted for their refusal to testify regarding t ...

, Edward Dmytryk

Edward Dmytryk (September 4, 1908 – July 1, 1999) was a Canadian-born American film director and editor. He was known for his 1940s films noir, noir films and received an Academy Award for Best Director, Oscar nomination for Best Director for ...

, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson

John Howard Lawson (September 25, 1894 – August 11, 1977) was an American playwright, screenwriter, arts critic, and cultural historian. After enjoying a relatively successful career writing plays that were staged on and off Broadway in the 192 ...

, Samuel Ornitz

Samuel Badisch Ornitz (November 15, 1890 – March 10, 1957) was an American screenwriter and novelist from New York City; he was one of the "Hollywood Ten"Obituary '' Variety'', March 13, 1957, page 63. who were blacklisted from the 1950s on by ...

, Adrian Scott

Robert Adrian Scott (February 6, 1911 – December 25, 1972) was an American screenwriter and film producer. He was one of the Hollywood Ten and later blacklisted by the Hollywood movie studio bosses.

Life and career Early life

Scott was born ...

, and Dalton Trumbo

James Dalton Trumbo (December 9, 1905 – September 10, 1976) was an American screenwriter who scripted many award-winning films, including ''Roman Holiday'' (1953), '' Exodus'', ''Spartacus'' (both 1960), and '' Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo'' (194 ...

.

Labor Movement

As a result of the strict anti-communist agenda of HUAC during the Red Scare, the Labor Movement was targeted by going after prominent union activists and leaders. HUAC found means to go after the unions by attaching a communist stigma to the many organizations and individuals.Harry Bridges

Harry Bridges (28 July 1901 – 30 March 1990) was an Australian-born American union leader, first with the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA). In 1937, he led several Pacific Coast chapters of the ILA to form a new union, the In ...

, a notable union activist and eventual union president of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU)

The International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) is a labor union which primarily represents dock workers on the West Coast of the United States, Hawaii, and in British Columbia, Canada; on the East Coast, the dominant union is the Intern ...

, was a direct target of such attacks. A campaign led by the committee chairman, at the time Martin Dies, focused on deporting the Australian American union activist directly based on testimony from John Frey claiming his Communist Party associations, despite his multiple public denials of such claims. Harry Bridges did although share a close intimacy with the Communist Party by aligning himself with certain aspects and ideals commonly targeted by HUAC giving reason for the subpoena and deportations attempts.

Advocacy Movement

Another target of the Dies Committee was Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. Flynn was a cofounder and a part of the board of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). She joined the Communist Party in 1937 and was even included in the party's Central Committee the following year. Because of her political associations, she was an easy individual for HUAC to target as they could also attack the ACLU. Martin Dies decided to publicly prosecute the organization in 1939 which forced a response form the ACLU. The response came in the form of shearing any connection with the Communist Party by ridding individuals with communist ties as an attempted plea to Martin Dies. This of course included Elizabeth Gurley Flynn who was expelled from the ACLU, even after being a part of the founding committee.Whittaker Chambers and Alger Hiss

On July 31, 1948, the committee heard testimony from Elizabeth Bentley, an American who had been working as a Soviet agent in

On July 31, 1948, the committee heard testimony from Elizabeth Bentley, an American who had been working as a Soviet agent in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

. Among those whom she named as communists was Harry Dexter White

Harry Dexter White (October 29, 1892 – August 16, 1948) was an American government official in the United States Department of the Treasury. Working closely with the secretary of the treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr., he helped set American financia ...

, a senior U.S. Treasury department official. The committee subpoenaed Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer and intelligence agent. After early years as a Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet spy (1932–1938), he defected from the Soviet u ...

on August 3, 1948. Chambers, too, was a former Soviet spy, by then a senior editor of ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' magazine.

Chambers named more than a half dozen government officials including White as well as Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official who was accused of espionage in 1948 for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. The statute of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjur ...

(and Hiss' brother Donald). Most of these former officials refused to answer committee questions, citing the Fifth Amendment. White denied the allegations, and died of a heart attack a few days later. Hiss also denied all charges; doubts about his testimony though, especially those expressed by freshman Congressman Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

, led to further investigation that strongly suggested Hiss had made a number of false statements.

Hiss challenged Chambers to repeat his charges outside a Congressional committee, which Chambers did. Hiss then sued for libel, leading Chambers to produce copies of State Department documents which he claimed Hiss had given him in 1938. Hiss denied this before a grand jury, was indicted for perjury, and subsequently convicted and imprisoned.

The present-day House of Representatives website on HUAC states, "But in the 1990s, Soviet archives conclusively revealed that Hiss had been a spy on the Kremlin's payroll." However, in the 1990s, senior Soviet intelligence officials, after consulting their archive, stated they found nothing to support that theory. In 1995, the National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA) is an intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the director of national intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collection, and proces ...

's Venona papers were alleged to have provided overwhelming evidence that Hiss was a spy, but the same evidence is also judged to be not only not overwhelming but entirely circumstantial. As a result, and also given how many documents remain classified, it is unlikely that a truly conclusive answer will ever be reached.

Ku Klux Klan (KKK)

In 1965, Klan violence prompted PresidentLyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

and Georgia congressman Charles L. Weltner to call for a congressional probe of the Ku Klux Klan. The resulting investigation resulted in numerous Klansmen remaining silent and giving evasive answers. The House of Representatives voted to cite seven Klan leaders, including Robert Shelton, for contempt of Congress for refusing to turn over Klan records. Shelton was found guilty and sentenced to one year in prison plus a $1,000 fine. Following his conviction, three other Klan leaders, Robert Scoggin, Bob Jones, and Calvin Craig, pleaded guilty. Scoggin and Jones were each sentenced to one year in prison, while Craig was fined $1,000. The charges against Marshall Kornegay, Robert Hudgins, and George Dorsett, were later dropped.

Decline

Following the censure of Joseph McCarthy (who never served in the House, nor on HUAC; he was a U.S. Senator), the prestige of HUAC began a gradual decline in the late 1950s. By 1959, the committee was being denounced by former President

Following the censure of Joseph McCarthy (who never served in the House, nor on HUAC; he was a U.S. Senator), the prestige of HUAC began a gradual decline in the late 1950s. By 1959, the committee was being denounced by former President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

as the "most un-American thing in the country today".

In May 1960, the committee held hearings in San Francisco City Hall

San Francisco City Hall is the seat of government for the City and County of San Francisco, California. Re-opened in 1915 in its open space area in the city's Civic Center, it is a Beaux-Arts monument to the City Beautiful movement that epito ...

which led to a riot on May 13, when city police officers fire-hosed protesting students from the UC Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after the Anglo-Irish philosopher George Berkele ...

, Stanford

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth governor of and th ...

, and other local colleges, and dragged them down the marble steps beneath the rotunda, leaving some seriously injured. Soviet affairs expert William Mandel, who had been subpoenaed to testify, angrily denounced the committee and the police in a blistering statement which was aired repeatedly for years thereafter on Pacifica Radio

Pacifica may refer to:

Art

* ''Pacifica'' (statue), a 1938 statue by Ralph Stackpole for the Golden Gate International Exposition

Places

* Pacifica, California, a city in the United States

** Pacifica Pier, a fishing pier

* Pacifica, a conce ...

station KPFA

KPFA (94.1 FM) is a public, listener-funded talk radio and music radio station located in Berkeley, California, broadcasting to the San Francisco Bay Area. KPFA airs public news, public affairs, talk, and music programming. The station signed o ...

in Berkeley. An anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

propaganda film, ''Operation Abolition'', was produced by the committee from subpoenaed local news reports, and shown around the country during 1960 and 1961. In response, the Northern California ACLU

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is an American nonprofit civil rights organization founded in 1920. ACLU affiliates are active in all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. The budget of the ACLU in 2024 was $383 million.

...

produced a film called ''Operation Correction'', which discussed falsehoods in the first film. Scenes from the hearings and protest were later featured in the Academy Award-nominated 1990 documentary '' Berkeley in the Sixties''. Women Strike for Peace also protested against HUAC at this time.

The committee lost considerable prestige as the 1960s progressed, increasingly becoming the target of political satirists and the defiance of a new generation of political activists. HUAC subpoenaed Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman

Abbot Howard Hoffman (November 30, 1936 – April 12, 1989) was an American political and social activist who co-founded the Youth International Party ("Yippies") and was a member of the Chicago Seven. He was also a leading proponent of the ...

of the Yippies

The Youth International Party (YIP), whose members were commonly called Yippies, was an American youth-oriented Radical politics, radical and Counterculture, countercultural revolutionary offshoot of the Free Speech Movement, free speech and an ...

in 1967, and again in the aftermath of the 1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus making ...

. The Yippies used the media attention to make a mockery of the proceedings. Rubin came to one session dressed as a Revolutionary War soldier and passed out copies of the United States Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America in the original printing, is the founding document of the United States. On July 4, 1776, it was adopted unanimously by the Second Continen ...

to those in attendance. Rubin then "blew giant gum bubbles, while his co-witnesses taunted the committee with Nazi salute

The Nazi salute, also known as the Hitler salute, or the ''Sieg Heil'' salute, is a gesture that was used as a greeting in Nazi Germany. The salute is performed by extending the right arm from the shoulder into the air with a straightened han ...

s". Rubin attended another session dressed as Santa Claus

Santa Claus (also known as Saint Nicholas, Saint Nick, Father Christmas, Kris Kringle or Santa) is a legendary figure originating in Western Christian culture who is said to bring gifts during the late evening and overnight hours on Chris ...

. On another occasion, police stopped Hoffman at the building entrance and arrested him for wearing the United States flag. Hoffman quipped to the press, "I regret that I have but one shirt to give for my country", paraphrasing the last words of revolutionary patriot Nathan Hale

Nathan Hale (June 6, 1755 – September 22, 1776) was an American Patriot (American Revolution), Patriot, soldier and spy for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He volunteered for an Military intelligence, intelligence ...

; Rubin, who was wearing a matching Viet Cong

The Viet Cong (VC) was an epithet and umbrella term to refer to the communist-driven armed movement and united front organization in South Vietnam. It was formally organized as and led by the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, and ...

flag, shouted that the police were communists for not arresting him as well.

Hearings in August 1966 called to investigate anti-Vietnam War activities were disrupted by hundreds of protesters, many from the Progressive Labor Party. The committee faced witnesses who were openly defiant.

According to ''The Harvard Crimson

''The Harvard Crimson'' is the student newspaper at Harvard University, an Ivy League university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. The newspaper was founded in 1873, and is run entirely by Harvard College undergraduate students.

His ...

'':

In an attempt to reinvent itself, the committee was renamed as the Internal Security Committee in 1969.

Termination

The House Committee on Internal Security was formally terminated on January 14, 1975, the day of the opening of the 94th Congress.Charles E. Schamel''Records of the US House of Representatives, Record Group 233: Records of the House Un-American Activities Committee, 1945–1969 (Renamed the) House Internal Security Committee, 1969–1976.''

Washington, DC: Center for Legislative Archives, National Archives and Records, July 1995; p. 4. The committee's files and staff were transferred on that day to the House Judiciary Committee.

Chairmen

Source:Eric Bentley, ''Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts from Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968.'' New York: The Viking Press 1971; pp. 955–957. * Martin Dies Jr., (D-Tex.), 1938–1944 * Edward J. Hart (D-N.J.), 1945–1946 *J. Parnell Thomas

John Parnell Thomas (January 16, 1895 – November 19, 1970) was an American stockbroker and politician. He was elected to seven terms as a U.S. Representative from New Jersey as a Republican, serving from 1937 to 1950.

Thomas later served nin ...

(R-N.J.), 1947–1948

*John Stephens Wood

John Stephens Wood (February 8, 1885 – September 12, 1968) was an American attorney and politician from the state of Georgia, United States. He served as a Democrat in the United States House of Representatives, 1931–1935 and 1945–1953. ...

(D-Ga.), 1949–1953

* Harold H. Velde (R-Ill.), 1953–1955

* Francis E. Walter (D-Pa.), 1955–1963

* Edwin E. Willis (D-La.), 1963–1969

* Richard Howard Ichord Jr. (D-Mo.), 1969–1975

Notable members

* Felix Edward Hébert * Donald L. Jackson * Noah M. Mason * Karl E. Mundt *Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

* John E. Rankin

* Gordon H. Scherer

* Richard B. Vail

* Jerry Voorhis

Horace Jeremiah "Jerry" Voorhis (April 6, 1901 – September 11, 1984) was an American politician and educator from California who served five terms in the United States House of Representatives from 1937 to 1947. A Democratic Party (Unit ...

See also

*California Senate Factfinding Subcommittee on Un-American Activities California Senate Factfinding Subcommittee on Un-American Activities (CUAC) was established by the California State Legislature in 1941 as the Joint Fact-Finding Committee on UnAmerican Activities. The creation of the new joint committee (with membe ...

* Defending Dissent Foundation

* Edith Alice Macia

* Edward S. Montgomery

* J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

* Jack Moffitt (screenwriter)

Jack Moffitt (May 8, 1901 – December 4, 1969), also credited at John C. Moffitt, was an American screenwriter and film critic. Employed by Universal Studios in the 1930s, he wrote screenplays for a number of minor films. Over the years he wrote ...

* Loyalty oath

Loyalty is a Fixation (psychology), devotion to a country, philosophy, group, or person. Philosophers disagree on what can be an object of loyalty, as some argue that loyalty is strictly interpersonal and only another human being can be the obj ...

* Lusk Committee

* Manning Johnson Manning Rudolph Johnson (December 17, 1908 – July 2, 1959)

was a Communist Party USA African-American leader and the party's candidate for U.S. Representative from New York's 22nd congressional district during a special election in 1935. Later, ...

* McCarthyism and antisemitism

The role of antisemitism during McCarthyism (also known as the Second Red Scare) has been noted and debated since the 1940s. In particular, the role of antisemitism during the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg has been debated both inside and ou ...

* McCarran Internal Security Act

The Internal Security Act of 1950, (Public Law 81-831), also known as the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950, the McCarran Act after its principal sponsor Sen. Pat McCarran (D-Nevada), or the Concentration Camp Law, is a United States f ...

* Mundt–Ferguson Communist Registration Bill

* Mundt–Nixon Bill

The Mundt–Nixon Bill, named after Karl Mundt and Richard Nixon, formally the Subversive Activities Control Act, was a proposed law in 1948 that would have required all members of the Communist Party of the United States register with the Attorne ...

* Red-baiting

Red-baiting, also known as ''reductio ad Stalinum'' () and red-tagging ( in the Philippines), is an intention to discredit the validity of a political opponent and the opponent's logical argument by accusing, denouncing, attacking, or persecuting ...

* Subversive Activities Control Board

* '' Wilkinson v. United States''

References

Works cited

*Further reading

Archives

Investigation of un-American propaganda activities in the United States. Hearings before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives (1938–1944), Volumes 1–17 with Appendices.

University of Pennsylvania online gateway to Internet Archive and Hathi Trust.

United States House Committee on Internal Security

University of Pennsylvania online gateway to Internet Archive and Hathi Trust. * Schamel, Gharles E. Inventory of records of the Special Committee on Un-American activities, 1938–1944 (the Dies committee). Center for Legislative Archives,

National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an independent agency of the United States government within the executive branch, charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It is also task ...

. Washington, D.C., July 1995.

* Schamel, Gharles E''Records of the House Un-American Activities committee, 1945–1969, renamed the House Internal Security committee, 1969–1976.''

Center for Legislative Archives, National Archives and Records Administration. Washington, D.C., July 1995. *

Books

* * * Caballero, Raymond. ''McCarthyism vs. Clinton Jencks.'' Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019. * * * * * * * *→ *→Articles

**

External links

* *History.House.gov

HUAC – permanent standing House Committee on Un-American Activities

History.House.gov

HUAC – 1948 Alger Hiss-Whittaker Chambers hearing before HUAC

Eastern Carolina University Libraries

The Cold War and Internal Security Collection (CWIS): HUAC

The Spartacus Educational website, UK * House Unamerican Activities Committee (HUAC) Collection: Pamphlets collected by HUAC, many of which the committee deemed "un-American". (4,000 pamphlets). From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

{{Authority control 1938 establishments in Washington, D.C. 1975 disestablishments in Washington, D.C. Anti-communist organizations in the United States Anti-fascist organizations in the United States Cold War history of the United States Un-American activities Government agencies established in 1938 McCarthyism Political repression in the United States