Diadochi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Diadochi were the rival generals, families, and friends of

The Diadochi were the rival generals, families, and friends of

Without a clear successor, Alexander's generals quickly began to dispute the rule of his empire. The two contenders were Alexander's half-brother Arrhidaeus and his unborn child with Roxana. Meleager and the

Without a clear successor, Alexander's generals quickly began to dispute the rule of his empire. The two contenders were Alexander's half-brother Arrhidaeus and his unborn child with Roxana. Meleager and the

The Wars of the Diadochi were a series of conflicts, fought between 322 and 275 BC, over the rule of Alexander's empire after his death.

In 310 BC Cassander secretly murdered Alexander IV and Roxana.

The Wars of the Diadochi were a series of conflicts, fought between 322 and 275 BC, over the rule of Alexander's empire after his death.

In 310 BC Cassander secretly murdered Alexander IV and Roxana.

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The Wars of the Diadochi mark the beginning of the Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

from the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

to the Indus River Valley.

The most notable Diadochi include Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

, Antigonus, Cassander, and Seleucus as the last remaining at the end of the Wars of the Successors, ruling in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, Asia-Minor, Macedon and Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

respectively, all forging dynasties lasting several centuries.

Background

Ancient role

In ancient Greek, is a noun (substantive or adjective) formed from the verb, ''diadechesthai'', "succeed to," a compound of ''dia-'' and ''dechesthai'', "receive." The word-set descends straightforwardly fromIndo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia (e. ...

*dek-, "receive", the substantive forms being from the o-grade, *dok-. Some important English reflexes are dogma, "a received teaching," decent, "fit to be received," paradox, "against that which is received." The prefix ''dia-'' changes the meaning slightly to add a social expectation to the received. The ''diadochos'', being a successor in command or any other office, ''expects'' to receive that office.

Basileus

It was exactly this expectation that contributed to strife in the Alexandrine and Hellenistic Ages, beginning with Alexander. Philip had married a woman who changed her name toOlympias

Olympias (; c. 375–316 BC) was a Ancient Greeks, Greek princess of the Molossians, the eldest daughter of king Neoptolemus I of Epirus, the sister of Alexander I of Epirus, the fourth wife of Philip of Macedon, Philip II, the king of Macedonia ...

to honor the coincidence of Philip's victory in the Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games (Olympics; ) are the world's preeminent international Olympic sports, sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a Multi-s ...

and Alexander's birth, an act that suggests love may have been a motive as well. Macedon's chief office was the ''basileia'', or monarchy, the chief officer being the ''basileus

''Basileus'' () is a Greek term and title that has signified various types of monarchs throughout history. In the English language, English-speaking world, it is perhaps most widely understood to mean , referring to either a or an . The title ...

'', now the signatory title of Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male name derived from the Macedonian Old Koine language, Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominen ...

. Their son and heir, Alexander, was raised with care, being educated by select prominent philosophers. Philip is said to have wept for joy when Alexander performed a feat of which no one else was capable, taming the wild horse, Bucephalus, at his first attempt in front of a skeptical audience including the king. Amidst the cheering onlookers Philip swore that Macedonia was not large enough for Alexander.

Philip built Macedonia into the leading military state of the Balkans. He had acquired his expertise fighting for Thebes and Greek freedom under his patron, Epaminondas. When Alexander was a teenager, Philip was planning a military solution to the contention with the Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, it was the larg ...

. In the opening campaign against Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion () was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' continued to be used as a n ...

he made Alexander "regent" (''kurios'') in his absence. Alexander used every opportunity to further his father's victories, expecting that he would be a part of them. At the report of each of Philip's victories, Alexander was said to lament that his father would leave him nothing of note to do.

There was a source of disaffection, however. Plutarch reports that Alexander and his mother bitterly reproached him for his numerous affairs among the women of his court. Philip then fell in love and married a young woman, Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (; The name Cleopatra is pronounced , or sometimes in both British and American English, see and respectively. Her name was pronounced in the Greek dialect of Egypt (see Koine Greek phonology). She was ...

, when he was too old for marriage. (Macedonian kings traditionally had multiple wives.) Alexander was at the wedding banquet when Attalus, Cleopatra's uncle, made a remark that seemed inappropriate to him. He asked the Macedonians to pray for an "heir to the kingship" (''diadochon tes basileias''). Rising to his feet Alexander shouted, using the royal "we," "Do we seem like bastards (''nothoi'') to you, evil-minded man?" and threw a cup at him. The inebriated Philip, rising to his feet and drawing his sword to defend Attalus, promptly fell. Making a comment that the man who was preparing to cross from Europe to Asia could not cross from one couch to another, Alexander departed, to escort his mother to her native Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

and to wait himself in Illyria. Not long after, prompted by Demaratus the Corinthian to mend the dissension in his house, Philip sent Demaratus to bring Alexander home. The expectation by virtue of which Alexander was ''diadochos'' was that as the son of Philip, he would inherit Philip's throne.

In 336 BC Philip was assassinated, and the 20-year-old Alexander "received the kingship" (''parelabe ten basileian''). In the same year Darius succeeded to the throne of Persia as '' Šâhe Šâhân'', "King of Kings," which the Greeks understood as " Great King." The role of the Macedonian ''basileus'' was changing fast. Alexander's army was already multinational. Alexander was acquiring dominion over state after state. His presence on the battlefield seemed to ensure immediate victory.

Hegemon

When Alexander the Great died on June 10, 323 BC, he left behind a huge empire which comprised many essentially independent territories. Alexander's empire stretched from his homeland of Macedon itself, along with the Greek city-states that his father had subdued, toBactria

Bactria (; Bactrian language, Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization in Central Asia based in the area south of the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) and north of the mountains of the Hindu Kush, an area ...

and parts of India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

in the east. It included parts of the present day Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

, Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

, and most of the former Achaemenid Empire, except for some lands the Achaemenids formerly held in Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

.

Successors

The hetairoi (), or companion cavalry, added flexibility to the ancient Macedonian army. The hetairoi were a specialcavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

unit composed of general officer

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

s without fixed rank, whom Alexander could assign where needed. They were typically from the nobility; many were related to Alexander. A parallel flexible structure in the Achaemenid army facilitated combined units.

Staff meetings to adjust command structure were nearly a daily event in Alexander's army. They created an ongoing expectation among the hetairoi of receiving an important and powerful command, if only for a short term. At the moment of Alexander's death, all possibilities were suddenly suspended. The hetairoi vanished with Alexander, to be replaced instantaneously by the Diadochi, men who knew where they had stood, but not where they would stand now. As there had been no definite ranks or positions of hetairoi, there were no ranks of Diadochi. They expected appointments, but without Alexander they would have to make their own.

For purposes of this presentation, the Diadochi are grouped by their rank and social standing at the time of Alexander's death. These were their initial positions as Diadochi.

Craterus

Craterus was an infantry and naval commander under Alexander during his conquest of theAchaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

. After the revolt of his army at Opis on the Tigris

The Tigris ( ; see #Etymology, below) is the eastern of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian Desert, Syrian and Arabia ...

in 324, Alexander ordered Craterus to command the veterans as they returned home to Macedonia. Antipater, commander of Alexander's forces in Greece and regent of the Macedonian throne in Alexander's absence, would lead a force of fresh troops back to Persia to join Alexander while Craterus would become regent in his place. When Craterus arrived at Cilicia in 323 BC, news reached him of Alexander's death. Though his distance from Babylon prevented him from participating in the distribution of power, Craterus hastened to Macedonia to assume the protection of Alexander's family. The news of Alexander's death caused the Greeks to rebel in the Lamian War. Craterus and Antipater defeated the rebellion in 322 BC. Despite his absence, the generals gathered at Babylon confirmed Craterus as Guardian of the Royal Family. However, with the royal family in Babylon, the Regent Perdiccas assumed this responsibility until the royal household could return to Macedonia.

Antipater

Antipater was an adviser to King Philip II, Alexander's father, a role he continued under Alexander. When Alexander left Macedon to conquer Persia in 334 BC, Antipater was named Regent of Macedon and General of Greece in Alexander's absence. In 323 BC, Craterus was ordered by Alexander to march his veterans back to Macedon and assume Antipater's position while Antipater was to march to Persia with fresh troops. Alexander's death that year, however, prevented the order from being carried out. When Alexander's generals gathered at the Partition of Babylon to divide the empire between themselves, Antipater was confirmed as General of Greece while the roles of Regent of the Empire and Guardian of the Royal Family were given to Perdiccas and Craterus, respectively. Together, the three men formed the top ruling group of the empire.Somatophylakes

The Somatophylakes were the seven bodyguards of Alexander.Macedonian satraps

Satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

s (Old Persian: ''xšaθrapāwn'') were the governors of the provinces in the Hellenistic empires.

Royal family

Non-Macedonian satraps and generals

The ''Epigoni''

Originally the Epigoni (/ɪˈpɪɡənaɪ/; from "offspring") were the sons of the Argive heroes who had fought in the first Theban war. In the 19th century the term was used to refer to the second generation of Diadochi rulers.Chronology

Struggle for unity (323–319 BC)

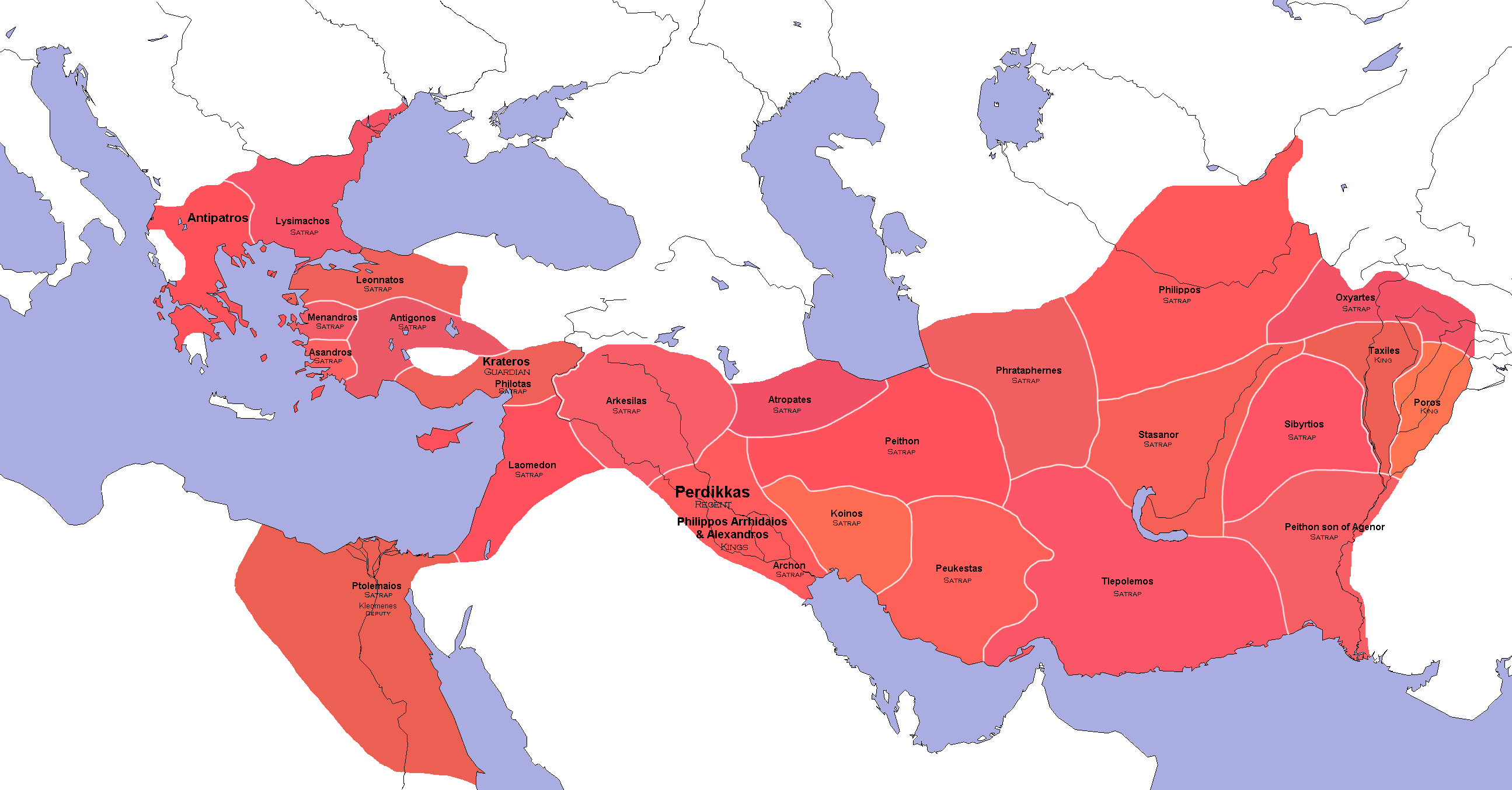

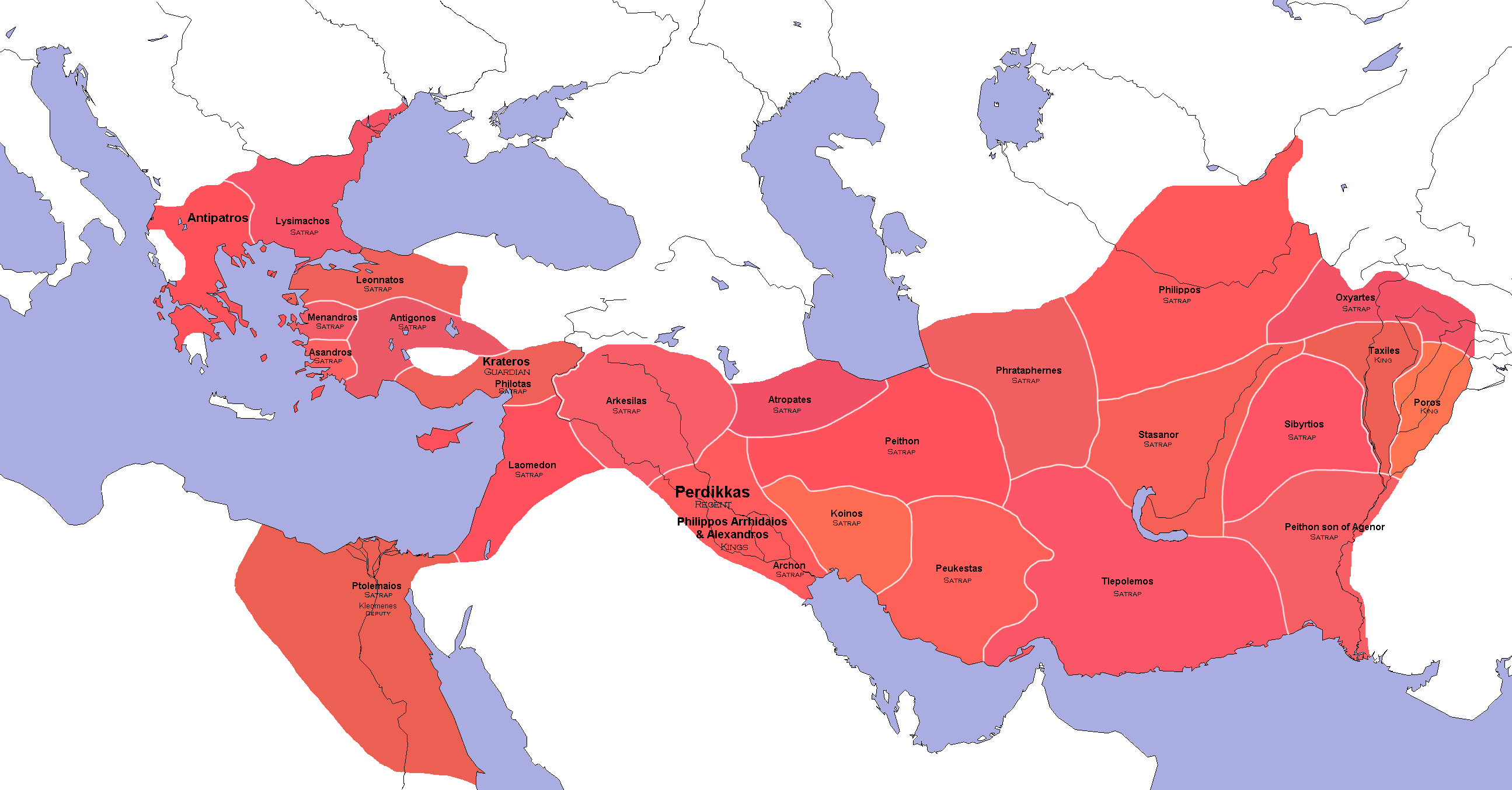

Partition of Babylon

Without a clear successor, Alexander's generals quickly began to dispute the rule of his empire. The two contenders were Alexander's half-brother Arrhidaeus and his unborn child with Roxana. Meleager and the

Without a clear successor, Alexander's generals quickly began to dispute the rule of his empire. The two contenders were Alexander's half-brother Arrhidaeus and his unborn child with Roxana. Meleager and the infantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

supported Arrhidaeus while Perdiccas and the cavalry supported waiting until the birth of Roxana's child.

A compromise was arranged, with Arrhidaeus being crowned as Philip III. If Roxana's child was a son, they would rule jointly. Perdiccas was named Regent and Meleager as his lieutenant. Eventually, Roxana did give birth to Alexander's son, Alexander IV. However, Perdiccas had Meleager and the other infantry leaders murdered and assumed full control.

Perdiccas, summoned a council of the great men of Alexander's court to appoint satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

s for the parts of the Empire in the partition of Babylon. Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

received Egypt; Laomedon received Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

and Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

; Philotas took Cilicia; Peithon took Media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Means of communication, tools and channels used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Interactive media, media that is inter ...

; Antigonus received Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; , ''Phrygía'') was a kingdom in the west-central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River.

Stories of the heroic age of Greek mythology tell of several legendary Ph ...

, Lycia

Lycia (; Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; , ; ) was a historical region in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is today the provinces of Antalya and Muğ ...

and Pamphylia; Asander received Caria

Caria (; from Greek language, Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; ) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Carians were described by Herodotus as being Anatolian main ...

; Menander received Lydia

Lydia (; ) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom situated in western Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey. Later, it became an important province of the Achaemenid Empire and then the Roman Empire. Its capital was Sardis.

At some point before 800 BC, ...

; Lysimachus received Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

; Leonnatus received Hellespontine Phrygia; and Neoptolemus had Armenia

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia. It is a part of the Caucasus region and is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia (country), Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to ...

. Macedon and the rest of Greece were to be jointly ruled by Antipater and Craterus, while Alexander's former secretary, Eumenes of Cardia, was to receive Cappadocia and Paphlagonia

Paphlagonia (; , modern translit. ''Paflagonía''; ) was an ancient region on the Black Sea coast of north-central Anatolia, situated between Bithynia to the west and Pontus (region), Pontus to the east, and separated from Phrygia (later, Galatia ...

.

Alexander's arrangements in the east were left intact. Taxiles and Porus governed over their kingdoms in India; Alexander's father-in-law Oxyartes governed Gandara; Sibyrtius governed Arachosia and Gedrosia

Gedrosia (; , ) is the Hellenization, Hellenized name of the part of coastal Balochistan that roughly corresponds to today's Makran. In books about Alexander the Great and his Diadochi, successors, the area referred to as Gedrosia runs from the I ...

; Stasanor governed Aria

In music, an aria (, ; : , ; ''arias'' in common usage; diminutive form: arietta, ; : ariette; in English simply air (music), air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrument (music), instrumental or orchestral accompan ...

and Drangiana; Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male name derived from the Macedonian Old Koine language, Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominen ...

governed Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian language, Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization in Central Asia based in the area south of the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) and north of the mountains of the Hindu Kush, an area ...

and Sogdia

Sogdia () or Sogdiana was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, and in present-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Sogdiana was also a province of the Achaemen ...

; Phrataphernes governed Parthia

Parthia ( ''Parθava''; ''Parθaw''; ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Medes during the 7th century BC, was incorporated into the subsequent Achaemeni ...

and Hyrcania; Peucestas governed Persis; Tlepolemus had charge over Carmania; Atropates governed northern Media; Archon

''Archon'' (, plural: , ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem , meaning "to be first, to rule", derived from the same ...

got Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

; and Arcesilaus governed northern Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

.

Revolt in Greece

Meanwhile, the news of Alexander's death had inspired a revolt in Greece, known as the Lamian War.Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and other cities joined, ultimately besieging Antipater in the fortress of Lamia. Antipater was relieved by a force sent by Leonnatus, who was killed in action, but the war did not come to an end until Craterus's arrival with a fleet to defeat the Athenians at the Battle of Crannon on September 5, 322 BC. For a time, this brought an end to any resistance to Macedonian domination. Meanwhile, Peithon suppressed a revolt of Greek settlers in the eastern parts of the Empire, and Perdiccas and Eumenes subdued Cappadocia.

First War of the Diadochi (322–320 BC)

Soon, however, conflict broke out. Perdiccas' marriage to Alexander's sisterCleopatra

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (; The name Cleopatra is pronounced , or sometimes in both British and American English, see and respectively. Her name was pronounced in the Greek dialect of Egypt (see Koine Greek phonology). She was ...

led Antipater, Craterus, Antigonus, and Ptolemy to join in rebellion. The actual outbreak of war was initiated by Ptolemy's theft of Alexander's body and its transfer to Egypt. Although Eumenes defeated the rebels in Asia Minor, in a battle at which Craterus was killed, it was all for nought, as Perdiccas himself was murdered by his own generals Peithon, Seleucus, and Antigenes during an invasion of Egypt.

Ptolemy came to terms with Perdiccas's murderers, making Peithon and Arrhidaeus regents in his place, but soon these came to a new agreement with Antipater at the Partition of Triparadisus. Antipater was made regent of the Empire, and the two kings were moved to Macedon. Antigonus remained in charge of Phrygia, Lycia, and Pamphylia, to which was added Lycaonia. Ptolemy retained Egypt, Lysimachus retained Thrace, while the three murderers of Perdiccas—Seleucus, Peithon, and Antigenes—were given the provinces of Babylonia, Media, and Susiana respectively. Arrhidaeus, the former Regent, received Hellespontine Phrygia. Antigonus was charged with the task of rooting out Perdiccas's former supporter, Eumenes. In effect, Antipater retained for himself control of Europe, while Antigonus, as leader of the largest army east of the Hellespont, held a similar position in Asia.

Partition of Triparadisus

Death of Antipater

Soon after the second partition, in 319 BC, Antipater died. Antipater had been one of the few remaining individuals with enough prestige to hold the empire together. After his death, war soon broke out again and the fragmentation of the empire began in earnest. Passing over his own son, Cassander, Antipater had declared Polyperchon his successor as Regent. A civil war soon broke out in Macedon and Greece between Polyperchon and Cassander, with the latter supported by Antigonus and Ptolemy. Polyperchon allied himself to Eumenes in Asia, but was driven from Macedonia by Cassander, and fled toEpirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

with the infant king Alexander IV and his mother Roxana. In Epirus he joined forces with Olympias

Olympias (; c. 375–316 BC) was a Ancient Greeks, Greek princess of the Molossians, the eldest daughter of king Neoptolemus I of Epirus, the sister of Alexander I of Epirus, the fourth wife of Philip of Macedon, Philip II, the king of Macedonia ...

, Alexander's mother, and together they invaded Macedon again. They were met by an army commanded by King Philip Arrhidaeus and his wife Eurydice, which immediately defected, leaving the king and Eurydice to Olympias's not so tender mercies, and they were killed (317 BC). Soon after, though, the tide turned, and Cassander was victorious, capturing and killing Olympias, and attaining control of Macedon, the boy king, and his mother.

Wars of the Diadochi (319–275 BC)

The Wars of the Diadochi were a series of conflicts, fought between 322 and 275 BC, over the rule of Alexander's empire after his death.

In 310 BC Cassander secretly murdered Alexander IV and Roxana.

The Wars of the Diadochi were a series of conflicts, fought between 322 and 275 BC, over the rule of Alexander's empire after his death.

In 310 BC Cassander secretly murdered Alexander IV and Roxana.

The Battle of Ipsus (301 BC)

The Battle of Ipsus at the end of the Fourth War of the Diadochi finalized the breakup of the unified Empire of Alexander. Antigonus I Monophthalmus and his son Demetrius I of Macedon were pitted against the coalition of three other companions of Alexander: Cassander, ruler of Macedon; Lysimachus, ruler of Thrace; and Seleucus I Nicator, ruler of Babylonia and Persia. Antigonus was killed, but his son Demetrius took a large part of Macedonia and continued his father's dynasty. After the death of Cassander and Lysimachus, following one another in fairly rapid succession, the Ptolemies and Seleucids controlled the vast majority of Alexander's former empire, with a much smaller segment controlled by the Antigonid dynasty until the 1st century.The ''Epigoni''

Kingdoms of the Diadochi (275–30 BC)

Ptolemaic Egypt

Under the rule of its first three monarchs Ptolemy I Soter, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, and Ptolemy III Euergetes, Ptolemaic Egypt reached its zenith of power and prestige in its first eighty years of existence, while heading off a number of crises and challenges along the way. The reign of Ptolemy IV Philopator (221–203 BC)is marked by historians as the beginning of the decline of Ptolemaic Egypt. However, the kingdom would persist for another 200 years. The Ptolemaic rulers gradually embraced Egyptian traditions, such as sibling royal marriages, which the Ptolemaic dynasty frequently partook in. The cosmopolitan nature of Ptolemaic Egypt can be seen with theRosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a Rosetta Stone decree, decree issued in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty of ancient Egypt, Egypt, on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts ...

, an edict ordered by Ptolemy V Epiphanes (204–180 BC), would be written in three languages: Egyptian hieroglyphs

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs ( ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined Ideogram, ideographic, logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with more than 1,000 distinct char ...

, Coptic, and Greek. However, the Ptolemaic rulers' insistence on the incorporation of Greek influences into Egyptian society led to many peasant revolts and uprisings throughout the course of the kingdom's existence.

Seleucid Empire

Antigonid Macedonia

Decline and fall

This division was to last for a century, before the Antigonid Kingdom finally fell to theRoman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

, and the Seleucids were harried from Persia by the Parthia

Parthia ( ''Parθava''; ''Parθaw''; ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Medes during the 7th century BC, was incorporated into the subsequent Achaemeni ...

ns and forced by the Romans to relinquish control in Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

. A rump Seleucid kingdom survived in Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

until finally conquered by Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey ( ) or Pompey the Great, was a Roman general and statesman who was prominent in the last decades of the Roman Republic. ...

in 64 BC. The Ptolemies lasted longer in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, though as a client under Rome. Egypt was finally annexed to Rome in 30 BC.

Historical uses as a title

Aulic

In the formal "court" titulature of the Hellenistic empires ruled by dynasties we know as Diadochs, the title was not customary for the Monarch, but has actually been proven to be the ''lowest'' in a system of official rank titles, known as Aulic titulature, conferred – ex officio or nominatim – to actual courtiers ''and'' as an honorary rank (for protocol) to various military and civilian officials. Notably in thePtolemaic Kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (; , ) or Ptolemaic Empire was an ancient Greek polity based in Ancient Egypt, Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Ancient Macedonians, Macedonian Greek general Ptolemy I Soter, a Diadochi, ...

, it was reported as the lowest aulic rank, under Philos, during the reign of Ptolemy V Epiphanes.

Modern concept

Diadochi (Διάδοχοι) is an ancient Greek word that currently modern scholars use to refer primarily to persons acting a role that existed only for a limited time period and within a limited geographic range. As there are no modern equivalents, it has been necessary to reconstruct the role from the ancient sources. There is no uniform agreement concerning exactly which historical persons fit the description, or the territorial range over which the role was in effect, or the calendar dates of the period. A certain basic meaning is included in all definitions, however. The New Latin terminology was introduced by the historians of universal Greek history of the 19th century. Their comprehensive histories of ancient Greece typically covering from prehistory to theRoman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

ran into many volumes. For example, George Grote in the first edition of ''History of Greece'', 1846–1856, hardly mentions the Diadochi, except to say that they were kings who came after Alexander and Hellenized Asia. In the edition of 1869 he defines them as "great officers of Alexander, who after his death carved kingdoms for themselves out of his conquests."

Grote cites no references for the use of Diadochi but his criticism of Johann Gustav Droysen gives him away. Droysen, "the modern inventor of Hellenistic history," not only defined "Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

" (''hellenistische ... Zeit''), but in a further study of the "successors of Alexander" (''nachfolger Alexanders'') dated 1836, after Grote had begun work on his history, but ten years before publication of the first volume, divided it into two periods, "the age of the Diadochi," or "Diadochi Period" (''die Zeit der Diodochen'' or ''Diadochenzeit''), which ran from the death of Alexander to the end of the "Diadochi Wars" (''Diadochenkämpfe'', his term), about 278 BC, and the "Epigoni Period" (''Epigonenzeit''), which ran to about 220 BC. He also called the Diadochi Period "the Diadochi War Period" (''Zeit der Diadochenkämpfe''). The Epigoni he defined as "Sons of the Diadochi" (''Diadochensöhne''). These were the second generation of Diadochi rulers. In an 1843 work, "History of the Epigoni" (''Geschichte der Epigonen'') he details the kingdoms of the Epigoni, 280-239 BC. The only precise date is the first, the date of Alexander's death, June, 323 BC. It has never been in question.

Grote uses Droysen's terminology but gives him no credit for it. Instead he attacks Droysen's concept of Alexander planting Hellenism in eastern colonies: "Plutarch states that Alexander founded more than seventy new cities in Asia. So large a number of them is neither verifiable nor probable, unless we either reckon up simple military posts or borrow from the list of foundations really established by his successors." He avoids Droysen's term in favor of the traditional "successor". In a long note he attacks Droysen's thesis as "altogether slender and unsatisfactory." Grote may have been right, but he ignores entirely Droysen's main thesis, that the concepts of "successors" and "sons of successors" were innovated and perpetuated by historians writing contemporaneously or nearly so with the period. Not enough evidence survives to prove it conclusively, but enough survives to win acceptance for Droysen as the founding father of Hellenistic history.

M. M. Austin localizes what he considers to be a problem with Grote's view. To Grote's assertion in the Preface to his work that the period "is of no interest in itself," but serves only to elucidate "the preceding centuries," Austin comments "Few nowadays would subscribe to this view." If Grote was hoping to minimize Droysen by not giving him credit, he was mistaken, as Droysen's gradually became the majority model. By 1898 Adolf Holm incorporated a footnote describing and evaluating Droysen's arguments. He describes the Diadochi and Epigoni as "powerful individuals." The title of the volume on the topic, however, is ''The Graeco-Macedonian Age...'', not Droysen's "Hellenistic".

Droysen's "Hellenistic" and "Diadochi Periods" are canonical today. A series of six (as of 2014) international symposia held at different universities 1997–2010 on the topics of the imperial Macedonians and their Diadochi have to a large degree solidified and internationalized Droysen's concepts. Each one grew out of the previous. Each published an assortment of papers read at the symposium. The 2010 symposium, entitled "The Time of the Diadochi (323-281 BC)," held at the University of A Coruña, Spain, represents the current concepts and investigations. The term Diadochi as an adjective is being extended beyond its original use, such as " Diadochi Chronicle," which is nowhere identified as such, or Diadochi kingdoms, "the kingdoms that emerged," even past the Age of the Epigoni.

See also

* PantodapoiReferences

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * *External links

* {{Authority control Offshoots of the Macedonian Empire 4th-century BC conflicts 3rd-century BC conflicts Wars involving ancient Greece Wars involving Macedonia (ancient kingdom) Alexander the Great Ancient Greek titles Macedonian Empire 4th century BC in Macedonia (ancient kingdom) 3rd century BC in Macedonia (ancient kingdom) he:מלחמות הדיאדוכים