Deutscher Bund on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The German Confederation ( ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in

,

Most historians have judged the Confederation to have been weak and ineffective, as well as an obstacle to the creation of a German nation-state. This weakness was part of its design, as the European Great Powers, including Prussia and especially Austria, did not want it to become a nation-state. However, the Confederation was not a loose tie between the German states, as it was impossible to leave the Confederation, and as Confederation law stood above the law of the aligned states. The constitutional weakness of the Confederation lay in the principle of unanimity in the Diet and the limits of the Confederation's scope: it was essentially a military alliance to defend Germany against external attacks and internal riots. The War of 1866 proved its ineffectiveness, as it was unable to combine the federal troops in order to fight the Prussian secession.

Most historians have judged the Confederation to have been weak and ineffective, as well as an obstacle to the creation of a German nation-state. This weakness was part of its design, as the European Great Powers, including Prussia and especially Austria, did not want it to become a nation-state. However, the Confederation was not a loose tie between the German states, as it was impossible to leave the Confederation, and as Confederation law stood above the law of the aligned states. The constitutional weakness of the Confederation lay in the principle of unanimity in the Diet and the limits of the Confederation's scope: it was essentially a military alliance to defend Germany against external attacks and internal riots. The War of 1866 proved its ineffectiveness, as it was unable to combine the federal troops in order to fight the Prussian secession.

The late 18th century was a period of political, economic, intellectual, and cultural reforms,

The late 18th century was a period of political, economic, intellectual, and cultural reforms,

German artists and intellectuals, heavily influenced by the French Revolution, turned to

German artists and intellectuals, heavily influenced by the French Revolution, turned to

Further efforts to improve the confederation began in 1834 with the establishment of a

Further efforts to improve the confederation began in 1834 with the establishment of a

The modern German nation state known as the Federal Republic is the continuation of the North German Confederation of 1867. This North German Confederation, a federal state, was a totally new creation: the law of the German Confederation ended, and new law came into existence. The German Confederation was, according to historian Kotulla, an association of states ''(Staatenbund)'' with some elements of a federal state ''(Bundesstaat)'', and the North German Confederation was a federal state with some elements of an association of states.

Still, the discussions and ideas of the period 1815–66 had a huge influence on the constitution of the North German Confederation. Most notably may be the Federal Council, the organ representing the member states. It is a certain copy of the 1815 Federal Convention of the German Confederation. The successor of that Federal Council of 1867 is the modern Bundesrat of the Federal Republic.

The German Confederation does not play a very prominent role in German historiography and national culture. It is mainly seen negatively as an instrument to oppress the liberal, democratic and national movements of the period. On the contrary, the March revolution (1849/49) with its events and institutions attract much more attention and partially devotion. The most important memorial sites are the Paulskirche in Frankfurt, which is now a cultural hall of national importance, and the Rastatt castle with the '' Erinnerungsstätte für die Freiheitsbewegungen in der deutschen Geschichte'' (a museum and memorial site for the freedom movements in the German history, not only the March revolution).

The remnants of the federal fortifications are certain tourists attractions at least regionally or for people interested in military history.

The modern German nation state known as the Federal Republic is the continuation of the North German Confederation of 1867. This North German Confederation, a federal state, was a totally new creation: the law of the German Confederation ended, and new law came into existence. The German Confederation was, according to historian Kotulla, an association of states ''(Staatenbund)'' with some elements of a federal state ''(Bundesstaat)'', and the North German Confederation was a federal state with some elements of an association of states.

Still, the discussions and ideas of the period 1815–66 had a huge influence on the constitution of the North German Confederation. Most notably may be the Federal Council, the organ representing the member states. It is a certain copy of the 1815 Federal Convention of the German Confederation. The successor of that Federal Council of 1867 is the modern Bundesrat of the Federal Republic.

The German Confederation does not play a very prominent role in German historiography and national culture. It is mainly seen negatively as an instrument to oppress the liberal, democratic and national movements of the period. On the contrary, the March revolution (1849/49) with its events and institutions attract much more attention and partially devotion. The most important memorial sites are the Paulskirche in Frankfurt, which is now a cultural hall of national importance, and the Rastatt castle with the '' Erinnerungsstätte für die Freiheitsbewegungen in der deutschen Geschichte'' (a museum and memorial site for the freedom movements in the German history, not only the March revolution).

The remnants of the federal fortifications are certain tourists attractions at least regionally or for people interested in military history.

Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

. It was created by the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, which had been dissolved in 1806 as a result of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

.

The Confederation had only one organ, the '' Bundesversammlung'', or Federal Convention (also Federal Assembly or Confederate Diet). The Convention consisted of the representatives of the member states. The most important issues had to be decided on unanimously. The Convention was presided over by the representative of Austria. This was a formality, however, as the Confederation did not have a head of state, since it was not a state.

The Confederation, on the one hand, was a strong alliance between its member states because federal law was superior to state law (the decisions of the Federal Convention were binding for the member states). Additionally, the Confederation had been established for eternity and was impossible to dissolve (legally), with no member states being able to leave it and no new member being able to join without universal consent in the Federal Convention. On the other hand, the Confederation was weakened by its very structure and member states, partly because the most important decisions in the Federal Convention required unanimity and the purpose of the Confederation was limited to only security matters. On top of that, the functioning of the Confederation depended on the cooperation of the two most populous member states, Austria and Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

which in reality were often in opposition.

The German revolutions of 1848–1849, motivated by liberal, democratic, socialist, and nationalist sentiments, attempted to transform the Confederation into a unified German federal state with a liberal constitution (usually called the Frankfurt Constitution in English). The Federal Convention was dissolved on 12 July 1848, but was re-established in 1850 after the revolution was crushed by Austria, Prussia, and other states.Deutsche Geschichte 1848/49,

Meyers Konversationslexikon

or was a major encyclopedia in the German language that existed in various editions, and by several titles, from 1839 to 1984, when it merged with the .

Joseph Meyer (1796–1856), who had founded the publishing house in 1826, intended to i ...

1885–1892

The Confederation was finally dissolved after the victory of the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

in the Seven Weeks' War over the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

in 1866. The dispute over which had the inherent right to rule German lands ended in favour of Prussia, leading to the creation of the North German Confederation

The North German Confederation () was initially a German military alliance established in August 1866 under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was transformed in the subsequent year into a confederated state (a ''de facto'' feder ...

under Prussian leadership in 1867, to which the eastern portions of the Kingdom of Prussia were added. A number of South German states remained independent until they joined the North German Confederation, which was renamed and proclaimed as the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

in 1871, as the unified Germany (aside from Austria) with the Prussian king as emperor (Kaiser) after the victory over French Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

in the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

of 1870.

History

Background

TheWar of the Third Coalition

The War of the Third Coalition () was a European conflict lasting from 1805 to 1806 and was the first conflict of the Napoleonic Wars. During the war, First French Empire, France and French client republic, its client states under Napoleon I an ...

lasted from about 1803 to 1806. Following defeat at the Battle of by the French under Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

in December 1805, Francis II abdicated as Holy Roman Emperor on 6 August 1806, thus dissolving the Empire

An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outpost (military), outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a hegemony, dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the ...

. In the aftermath of the Treaty of Napoleon created the Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederated States of the Rhine, simply known as the Confederation of the Rhine or Rhine Confederation, was a confederation of German client states established at the behest of Napoleon some months after he defeated Austrian Empire, Austria ...

in July 1806, joining sixteen of France's allies among the German states (including Bavaria and ). After the Battle of of October 1806 in the War of the Fourth Coalition

The War of the Fourth Coalition () was a war spanning 1806–1807 that saw a multinational coalition fight against Napoleon's First French Empire, French Empire, subsequently being defeated. The main coalition partners were Kingdom of Prussia, ...

, various other German states, including Saxony and Westphalia, also joined the Confederation. Only Austria, Prussia, Danish , Swedish Pomerania

Swedish Pomerania (; ) was a dominions of Sweden, dominion under the Sweden, Swedish Crown from 1630 to 1815 on what is now the Baltic Sea, Baltic coast of Germany and Poland. Following the Polish-Swedish War, Polish War and the Thirty Years' War ...

, and the French-occupied Principality of Erfurt stayed outside the Confederation of the Rhine. The War of the Sixth Coalition

In the War of the Sixth Coalition () (December 1812 – May 1814), sometimes known in Germany as the Wars of Liberation (), a coalition of Austrian Empire, Austria, Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia, Russian Empire, Russia, History of Spain (1808– ...

from 1812 to winter 1814 saw the defeat of Napoleon and the liberation of Germany. In June 1814, the famous German patriot Heinrich vom Stein created the Central Managing Authority for Germany (''Zentralverwaltungsbehörde'') in Frankfurt to replace the defunct Confederation of the Rhine. However, plenipotentiaries gathered at the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

were determined to create a weaker union of German states than that envisaged by Stein.

Establishment

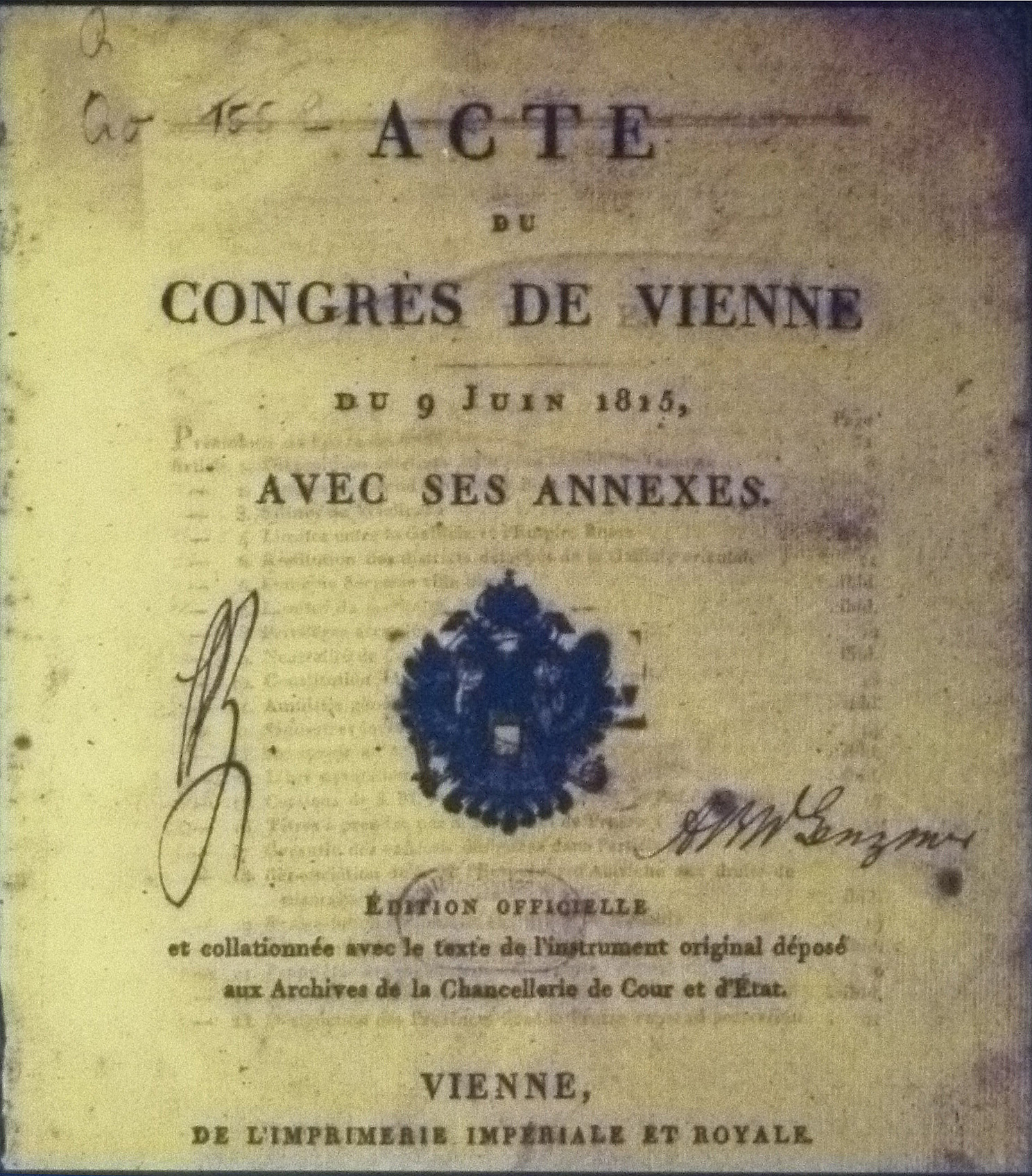

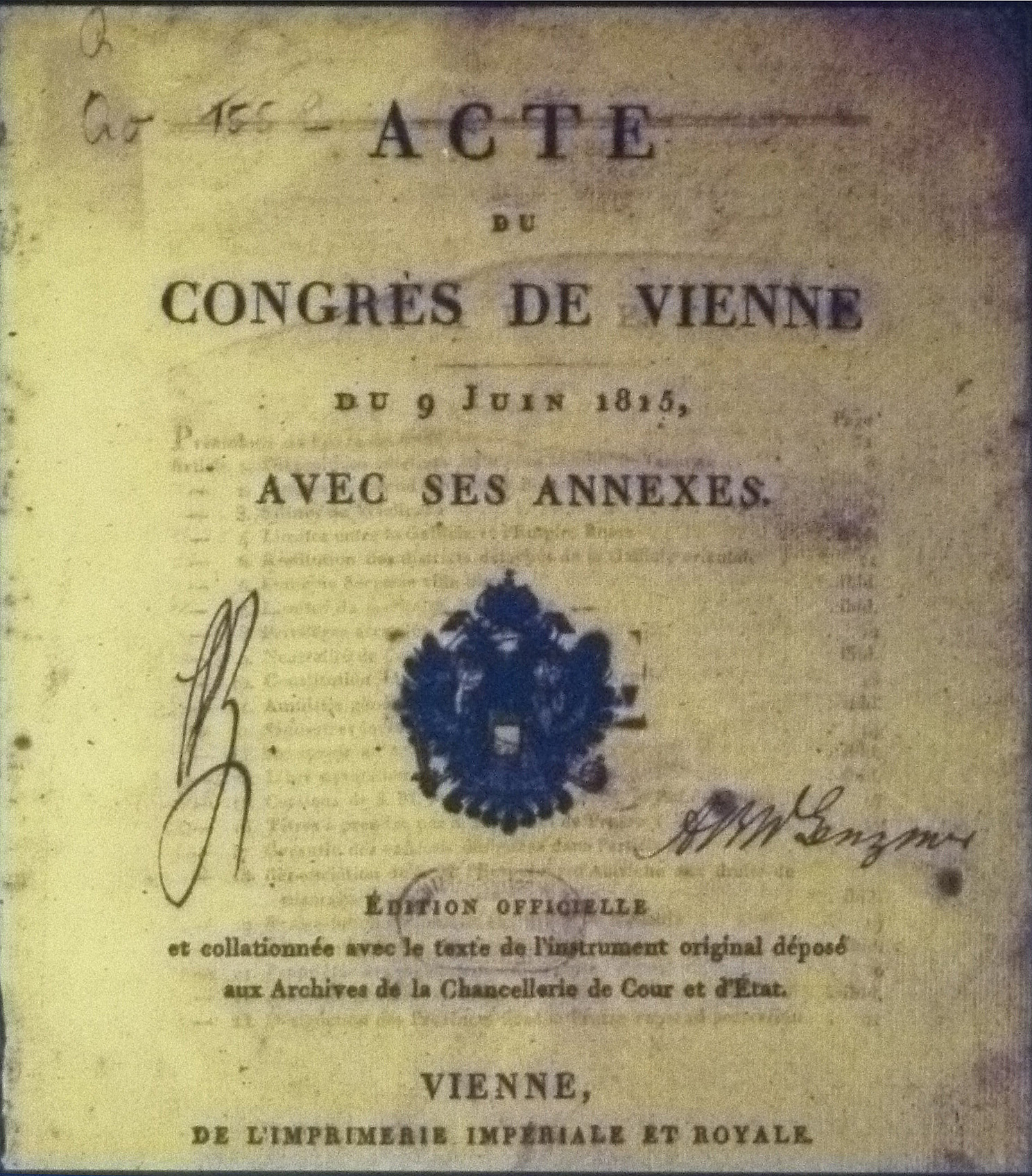

The German Confederation was created by the 9th Act of the Congress of Vienna on 8 June 1815 after being alluded to in Article 6 of the 1814 Treaty of Paris, ending the War of the Sixth Coalition. The Confederation was formally created by a second treaty, the ''Final Act of the Ministerial Conference to Complete and Consolidate the Organization of the German Confederation''. This treaty was not concluded and signed by the parties until 15 May 1820. States joined the German Confederation by becoming parties to the second treaty. The states designated for inclusion in the Confederation were: In 1839, as compensation for the loss of part of the province of to Belgium, theDuchy of Limburg

The Duchy of Limburg or Limbourg was an imperial estate of the Holy Roman Empire. Much of the area of the duchy is today located within Liège Province of Belgium, with a small portion in the municipality of Voeren, an Enclave and exclave, excla ...

was created and became a member of the German Confederation (held by the Netherlands jointly with Luxembourg) until the dissolution of 1866. In 1867 the duchy was declared to be an "integral part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands". The cities of Maastricht and Venlo were not included in the Confederation.

The Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

and the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

were the largest and by far the most powerful members of the Confederation. Large parts of both countries were not included in the Confederation, because they had not been part of the former Holy Roman Empire, nor were the greater parts of their armed forces incorporated in the federal army. Austria and Prussia each had one vote in the Federal Assembly.

Six other major states had one vote each in the Federal Assembly: the Kingdom of Bavaria

The Kingdom of Bavaria ( ; ; spelled ''Baiern'' until 1825) was a German state that succeeded the former Electorate of Bavaria in 1806 and continued to exist until 1918. With the unification of Germany into the German Empire in 1871, the kingd ...

, the Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony () was a German monarchy in Central Europe between 1806 and 1918, the successor of the Electorate of Saxony. It joined the Confederation of the Rhine after the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, later joining the German ...

, the Kingdom of , the Electorate of Hesse

The Electorate of Hesse (), also known as Hesse-Kassel or Kurhessen, was the title used for the former Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel after an 1803 reform where the Holy Roman Emperor elevated its ruler to the rank of Elector, thus giving him ...

, the Grand Duchy of Baden

The Grand Duchy of Baden () was a German polity on the east bank of the Rhine. It originally existed as a sovereign state from 1806 to 1871 and later as part of the German Empire until 1918.

The duchy's 12th-century origins were as a Margravia ...

, and the Grand Duchy of Hesse

The Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine () was a grand duchy in western Germany that existed from 1806 to 1918. The grand duchy originally formed from the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt in 1806 as the Grand Duchy of Hesse (). It assumed the name ...

.

Three foreign monarchs ruled member states: the King of Denmark

The monarchy of Denmark is a constitutional political system, institution and a historic office of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Kingdom includes Denmark proper and the autonomous administrative division, autonomous territories of the Faroe Is ...

as Duke of Holstein

Holstein (; ; ; ; ) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider (river), Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost States of Germany, state of Germany.

Holstein once existed as the German County of Holstein (; 8 ...

and Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg

The Duchy of Saxe-Lauenburg (, ), was a ''reichsfrei'' duchy that existed from 1296 to 1803 and again from 1814 to 1876 in the extreme southeast region of what is now Schleswig-Holstein. Its territorial centre was in the modern district of Herz ...

; the King of the Netherlands

The monarchy of the Netherlands is governed by the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands, country's charter and Constitution of the Netherlands, constitution, roughly a third of which explains the mechanics of succession, accession, and a ...

as Grand Duke of Luxembourg

The Grand Duke of Luxembourg is the head of state of Luxembourg. Luxembourg has been a grand duchy since 15 March 1815, when it was created from territory of the former Duchy of Luxembourg. It was in personal union with the United Kingdom of ...

and (from 1839) Duke of Limburg; and the King of the United Kingdom

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers Constitutional monarchy, regula ...

(until 1837) as King of Hanover

The King of Hanover () was the official title of the head of state and Hereditary monarchy, hereditary ruler of the Kingdom of Hanover, beginning with the proclamation of List of British monarchs, King George III of the United Kingdom, as "King o ...

were members of the German Confederation. Each of them had a vote in the Federal Assembly. At its foundation in 1815, four member states were ruled by foreign monarchs, as the King of Denmark was Duke of both Holstein and Saxe-Lauenburg.

The four free cities of , , , and shared one vote in the Federal Assembly.

The 23 remaining states (at its formation in 1815) shared five votes in the Federal Assembly:

* Saxe-Weimar, Saxe-Meiningen, Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld and Saxe-Hildburghausen (5 states)

* Brunswick and Nassau (2 states)

* Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz (2 states)

* Oldenburg, Anhalt-Dessau, Anhalt-Bernburg, Anhalt-Köthen, Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt and Schwarzburg-Sondershausen (6 states)

* Hohenzollern-Hechingen, Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, Liechtenstein, Reuss (Elder Branch), Reuss (Younger Branch), Schaumburg-Lippe, Lippe and Waldeck (8 states)

There were therefore 17 votes in the Federal Assembly.

Military

Activities

The rules of the Confederation provided for three different types of military interventions: * the federal war (''Bundeskrieg'') against an external enemy who attacks federal territory, * the federal execution (''Bundesexekution'') against the government of a member state that violates federal law, * the federal intervention (''Bundesintervention'') supporting a government that is under pressure of a popular uprising. Other military conflicts were foreign to the confederation (''bundesfremd''). An example is Austria's oppression of the uprising in Northern Italy in 1848 and 1849, as these Austrian territories lay outside of the confederation's borders. During the existence of the Confederation, there was only one federal war: the war against Denmark beginning with the Schleswig-Holstein uprising in 1848 (theFirst Schleswig War

The First Schleswig War (), also known as the Schleswig-Holstein uprising () and the Three Years' War (), was a military conflict in southern Denmark and northern Germany rooted in the Schleswig–Holstein question: who should control the Du ...

). The conflict became a federal war when the Bundestag demanded from Denmark to withdraw its troops from Schleswig (April 12) and recognized the revolutionary of Schleswig-Holstein (April 22). The confederation was transformed into the German Empire of 1848. Prussia was ''de facto'' the most important member state conducting the war for Germany.

There are several examples for federal executions and especially federal interventions. In 1863, the Confederation ordered a federal execution against the duke of Holstein (the Danish king). Federal troops occupied Holstein which was a member state. After this, Austria and Prussia declared war on Denmark, the Second Schleswig War (or ''Deutsch-Dänischer Krieg'' in German). As Schleswig and Denmark were not member states, this war was foreign to the Confederation. The Confederation took no part in this war.

A federal intervention confronted for example the raid of the revolutionaries in Baden in April 1848.

In June 1866, the Federal Convention decided to takes measures against Prussia. This decision was technically not a federal execution for a lack of time to observe the actual procedure. Prussia had violated, according to the majority of the convention, federal law by sending its troops to Holstein. The decision led to the war in summer 1866 that ended with the dissolution of the confederation ( known as ''Seven Weeks War'' or by other names).

Armed forces

The German Federal Army (''Deutsches Bundesheer'') was supposed to collectively defend the German Confederation from external enemies, primarily France. Successive laws passed by the Confederate Diet set the form and function of the army, as well as contribution limits of the member states. The Diet had the power to declare war and was responsible for appointing a supreme commander of the army and commanders of the individual army corps. This made mobilization extremely slow and added a political dimension to the army. In addition, the Diet oversaw the construction and maintenance of several German Federal Fortresses and collected funds annually from the member states for this purpose. Projections of army strength were published in 1835, but the work of forming the Army Corps did not commence until 1840 as a consequence of the Rhine Crisis. Money for the fortresses were determined by an act of the Confederate Diet in that year. By 1846, Luxemburg still had not formed its own contingent, and Prussia was rebuffed for offering to supply 1,450 men to garrison the Luxemburg fortress that should have been supplied by Waldeck and the two Lippes. In that same year, it was decided that a common symbol for the Federal Army should be the old Imperial two-headed eagle, but without crown, scepter, or sword, as any of those devices encroached on the individual sovereignty of the states. KingFrederick William IV of Prussia

Frederick William IV (; 15 October 1795 – 2 January 1861), the eldest son and successor of Frederick William III of Prussia, was King of Prussia from 7 June 1840 until his death on 2 January 1861. Also referred to as the "romanticist on the th ...

was among those who derided the "disarmed imperial eagle" as a national symbol.

The German Federal Army was divided into ten Army Corps (later expanded to include a Reserve Corps). However, the Army Corps were not exclusive to the German Confederation but composed from the national armies of the member states, and did not include all of the armed forces of a state. For example, Prussia's army consisted of nine Army Corps but contributed only three to the German Federal Army.

The strength of the mobilized German Federal Army was projected to total 303,484 men in 1835 and 391,634 men in 1860, with the individual states providing the following figures:

; Notes

Historical context

Between 1806 and 1815,Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

organized the German states, aside from Prussia and Austria, into the Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederated States of the Rhine, simply known as the Confederation of the Rhine or Rhine Confederation, was a confederation of German client states established at the behest of Napoleon some months after he defeated Austrian Empire, Austria ...

, but this collapsed after his defeats in 1812 to 1815. The German Confederation had roughly the same boundaries as the Empire at the time of the French Revolution (less what is now Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

). It also kept intact most of Confederation's reconstituted member states and their boundaries. The member states

A member state is a state that is a member of an international organization or of a federation or confederation.

Since the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) include some members that are not sovereign states ...

, drastically reduced to 39 from more than 300 (see ) under the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, were recognized as fully sovereign. The members pledged themselves to mutual defense, and joint maintenance of the fortresses at Mainz

Mainz (; #Names and etymology, see below) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate, and with around 223,000 inhabitants, it is List of cities in Germany by population, Germany's 35th-largest city. It lies in ...

, the city of Luxembourg

Luxembourg, officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France on the south. Its capital and most populous city, Luxembour ...

, , , and .

The only organ of the Confederation was the Federal Assembly (officially , often called ), which consisted of the delegates of the states' governments. There was no head of state, but the Austrian delegate presided over the Assembly (according to the Bundesakte). Austria did not have extra powers, but consequently the Austrian delegate was called and Austria the (presiding power). The Assembly met in Frankfurt.

The Confederation was enabled to accept and deploy ambassadors. It allowed ambassadors of the European powers to the Assembly, but rarely deployed ambassadors itself.

During the revolution of 1848/49 the Federal Assembly was inactive. It transferred its powers to the , the revolutionary German Central Government of the Frankfurt National Assembly. After crushing the revolution and illegally disbanding the National Assembly, the Prussian King failed to create a German nation state by himself. The Federal Assembly was revived in 1850 on Austrian initiative, but only fully reinstalled in the Summer of 1851.

Rivalry between Prussia and Austria grew more and more, especially after 1859. The Confederation was dissolved in 1866 after the Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War (German: ''Preußisch-Österreichischer Krieg''), also known by many other names,Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Second War of Unification, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), ''Deutsc ...

, and was succeeded in 1866 by the Prussian-dominated North German Confederation

The North German Confederation () was initially a German military alliance established in August 1866 under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was transformed in the subsequent year into a confederated state (a ''de facto'' feder ...

. Unlike the German Confederation, the North German Confederation was in fact a true state. Its territory comprised the parts of the German Confederation north of the river Main, plus Prussia's eastern territories and the Duchy of , but excluded Austria and the other southern German states.

Prussia's influence was widened by the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

resulting in the proclamation of the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

at on 18 January 1871, which united the North German Federation with the southern German states. All the constituent states of the former German Confederation became part of the in 1871, except Austria, Luxembourg

Luxembourg, officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France on the south. Its capital and most populous city, Luxembour ...

, the Duchy of Limburg

The Duchy of Limburg or Limbourg was an imperial estate of the Holy Roman Empire. Much of the area of the duchy is today located within Liège Province of Belgium, with a small portion in the municipality of Voeren, an Enclave and exclave, excla ...

, and Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (, ; ; ), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein ( ), is a Landlocked country#Doubly landlocked, doubly landlocked Swiss Standard German, German-speaking microstate in the Central European Alps, between Austria in the east ...

.

Impact of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic invasions

The late 18th century was a period of political, economic, intellectual, and cultural reforms,

The late 18th century was a period of political, economic, intellectual, and cultural reforms, the Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empirici ...

(represented by figures such as Locke, , , and Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

), but also involving early Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

, and climaxing with the French Revolution, where freedom of the individual and nation was asserted against privilege and custom. Representing a great variety of types and theories, they were largely a response to the disintegration of previous cultural patterns, coupled with new patterns of production, specifically the rise of industrial capitalism.

However, the defeat of Napoleon enabled conservative and reactionary regimes such as those of the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

, the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

, and Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

ist Russia to survive, laying the groundwork for the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

and the alliance that strove to oppose radical demands for change ushered in by the French Revolution. With Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

's position on the continent now intact and ostensibly secure under its reactionary premier , the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

empire would serve as a barrier to contain the emergence of Italian and German nation-states as well, in addition to containing France. But this reactionary balance of power, aimed at blocking German and Italian nationalism

Italian nationalism () is a movement which believes that the Italians are a nation with a single homogeneous identity, and therefrom seeks to promote the cultural unity of Italy as a country. From an Italian nationalist perspective, Italianness i ...

on the continent, was precarious.

After Napoleon's final defeat in 1815, the surviving member states of the defunct Holy Roman Empire joined to form the German Confederation ()a rather loose organization, especially because the two great rivals, the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

and the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

, each feared domination by the other.

In Prussia the rulers forged a centralized state. By the time of the Napoleonic Wars, Prussia, grounded in the virtues of its established military aristocracy (the ') and stratified by rigid hierarchical lines, had been surpassed militarily and economically by France. After 1807, Prussia's defeats by Napoleonic France highlighted the need for administrative, economic, and social reforms to improve the efficiency of the bureaucracy and encourage practical merit-based education. Inspired by the Napoleonic organization of German and Italian principalities, the Prussian Reform Movement

The Prussian Reform Movement was a series of constitutional, administrative, social, and economic reforms early in 19th-century Prussia. They are sometimes known as the Stein–Hardenberg Reforms, for Karl Freiherr vom Stein and Karl August v ...

led by and Count was conservative, enacted to preserve aristocratic

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense economic, political, and social influence. In Western Christian co ...

privilege while modernizing institutions.

Outside Prussia, industrialization progressed slowly, and was held back because of political disunity, conflicts of interest between the nobility and merchants, and the continued existence of the guild system, which discouraged competition and innovation. While this kept the middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

at bay, affording the old order a measure of stability not seen in France, Prussia's vulnerability to Napoleon's military proved to many among the old order that a fragile, divided, and traditionalist Germany would be easy prey for its cohesive and industrializing neighbor.

The reforms laid the foundation for Prussia's future military might by professionalizing the military and decreeing universal military conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

. In order to industrialize Prussia, working within the framework provided by the old aristocratic institutions, land reforms were enacted to break the monopoly of the ''s'' on land ownership, thereby also abolishing, among other things, the feudal practice of serfdom.

Romanticism, nationalism, and liberalism in the era

Although the forces unleashed by the French Revolution were seemingly under control after the Vienna Congress, the conflict between conservative forces and liberal nationalists was only deferred at best. The era until the failed 1848 revolution, in which these tensions built up, is commonly referred to as ("pre-March"), in reference to the outbreak of riots in March 1848. This conflict pitted the forces of the old order against those inspired by the French Revolution and the Rights of Man. The breakdown of the competition was, roughly, the emergingcapitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

and petit-bourgeoisie (engaged mostly in commerce, trade, and industry), and the growing (and increasingly radicalized) industrial working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

; and the other side associated with landowning aristocracy or military aristocracy (the ''s'') in Prussia, the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

monarchy in Austria, and the conservative notables of the small princely states and city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

s in Germany.

Meanwhile, demands for change from below had been fomenting due to the influence of the French Revolution. Throughout the German Confederation, Austrian influence was paramount, drawing the ire of the nationalist movements. considered nationalism, especially the nationalist youth movement, the most pressing danger: German nationalism might not only repudiate Austrian dominance of the Confederation, but also stimulate nationalist sentiment within the Austrian Empire itself. In a multi-national polyglot

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. When the languages are just two, it is usually called bilingualism. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolin ...

state in which Slavs and Magyars outnumbered the Germans, the prospects of Czech, Slovak, Hungarian, Polish, Serb, or Croatian sentiment along with middle class liberalism was certainly horrifying to the monarchist landed aristocracy.

Figures like , , , , , , and rose in the era. Father 's gymnastic associations exposed middle class German youth to nationalist and democratic ideas, which took the form of the nationalistic and liberal democratic college fraternities known as the . The Wartburg Festival in 1817 celebrated Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

as a proto-German nationalist, linking Lutheranism to German nationalism, and helping arouse religious sentiments for the cause of German nationhood. The festival culminated in the burning of several books and other items that symbolized reactionary

In politics, a reactionary is a person who favors a return to a previous state of society which they believe possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary.''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'' Third Edition, (1999) p. 729. ...

attitudes. One item was a book by . In 1819, was accused of spying for Russia, and then murdered by a theological student, , who was executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

for the crime. Sand belonged to a militant nationalist faction of the . used the murder as a pretext to issue the Carlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees () were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town of Carlsbad, Austrian Empire. ...

of 1819, which dissolved the , cracked down on the liberal press, and seriously restricted academic freedom

Academic freedom is the right of a teacher to instruct and the right of a student to learn in an academic setting unhampered by outside interference. It may also include the right of academics to engage in social and political criticism.

Academic ...

.

High culture

German artists and intellectuals, heavily influenced by the French Revolution, turned to

German artists and intellectuals, heavily influenced by the French Revolution, turned to Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

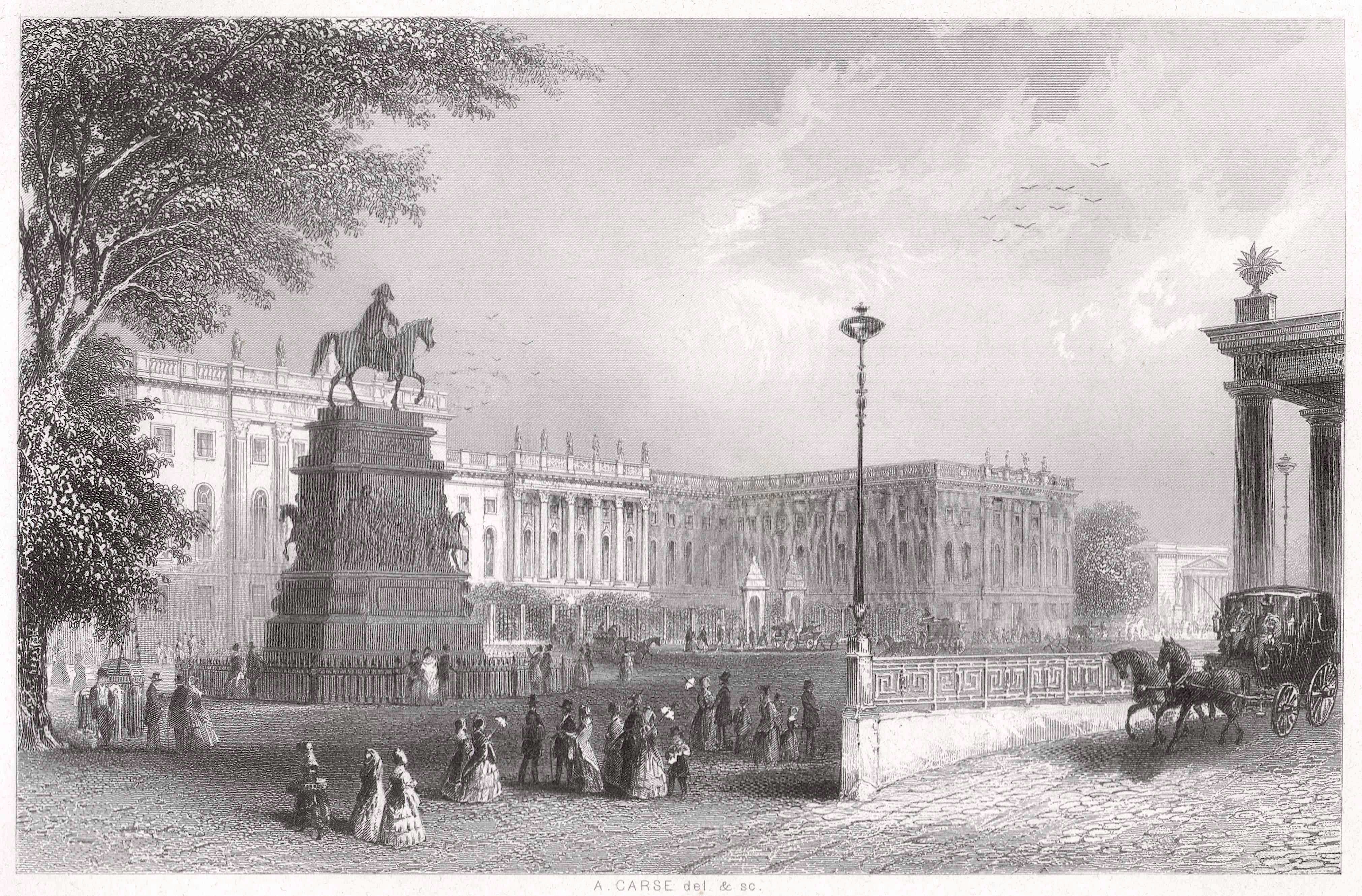

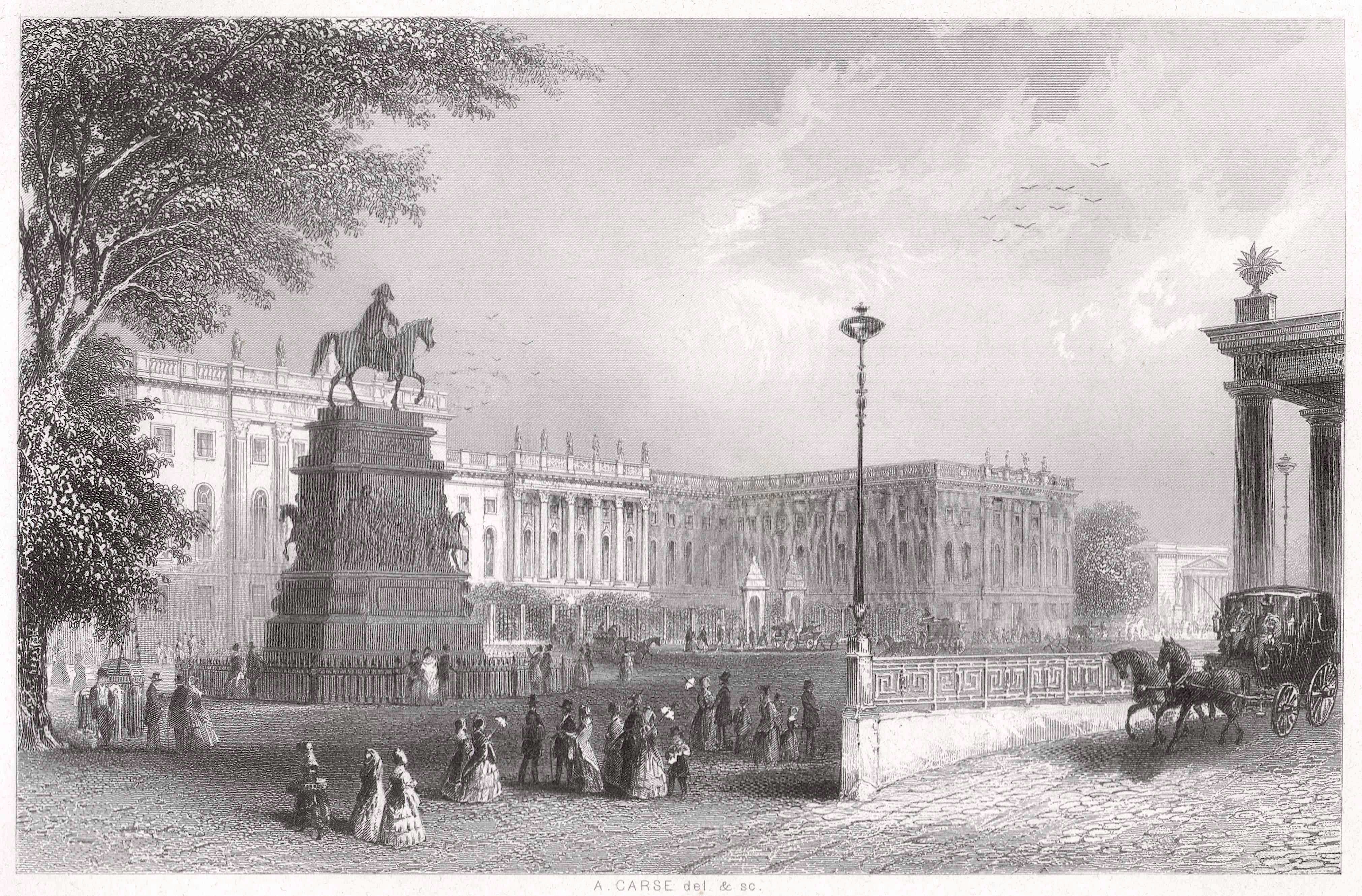

. At the universities, high-powered professors developed international reputations, especially in the humanities led by history and philology, which brought a new historical perspective to the study of political history, theology, philosophy, language, and literature. With (1770–1831) in philosophy, (1768–1834) in theology and (1795–1886) in history, the University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin (, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin, Germany.

The university was established by Frederick William III on the initiative of Wilhelm von Humbol ...

, founded in 1810, became the world's leading university. , for example, professionalized history and set the world standard for historiography. By the 1830s, mathematics, physics, chemistry, and biology had emerged with world class science, led by (1769–1859) in natural science and (1777–1855) in mathematics. Young intellectuals often turned to politics, but their support for the failed Revolution of 1848 forced many into exile.

Population

Demographic transition

The population of the German Confederation (excluding Austria) grew 60% from 1815 to 1865, from 21,000,000 to 34,000,000. The era saw thedemographic transition

In demography, demographic transition is a phenomenon and theory in the Social science, social sciences referring to the historical shift from high birth rates and high Mortality rate, death rates to low birth rates and low death rates as societi ...

take place in Germany. It was a transition from high birth rates and high death rates to low birth and death rates as the country developed from a pre-industrial to a modernized agriculture and supported a fast-growing industrialized urban economic system. In previous centuries, the shortage of land meant that not everyone could marry, and marriages took place after age 25. The high birthrate was offset by a very high rate of infant mortality

Infant mortality is the death of an infant before the infant's first birthday. The occurrence of infant mortality in a population can be described by the infant mortality rate (IMR), which is the number of deaths of infants under one year of age ...

, plus periodic epidemics and harvest failures. After 1815, increased agricultural productivity meant a larger food supply, and a decline in famines, epidemics, and malnutrition. This allowed couples to marry earlier, and have more children. Arranged marriages became uncommon as young people were now allowed to choose their own marriage partners, subject to a veto by the parents. The upper and middle classes began to practice birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

, and a little later so too did the peasants. The population in 1800 was heavily rural, with only 8% of the people living in communities of 5,000 to 100,000 and another 2% living in cities of more than 100,000.

Nobility

In a heavily agrarian society, land ownership played a central role. Germany's nobles, especially those in the East called ', dominated not only the localities, but also thePrussian court

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signi ...

, and especially the Prussian army. Increasingly after 1815, a centralized Prussian government based in Berlin took over the powers of the nobles, which in terms of control over the peasantry had been almost absolute. They retained control of the judicial system on their estates until 1848, as well as control of hunting and game laws. They paid no land tax until 1861 and kept their police authority until 1872, and controlled church affairs into the early 20th century. To help the nobility avoid indebtedness, Berlin set up a credit institution to provide capital loans in 1809, and extended the loan network to peasants in 1849. When the German Empire was established in 1871, the nobility controlled the army and the Navy, the bureaucracy, and the royal court; they generally set governmental policies.

Peasantry

Peasants continued to center their lives in the village, where they were members of a corporate body and helped manage community resources and monitor community life. In the East, they were serfs who were bound prominently to parcels of land. In most of Germany, farming was handled by tenant farmers who paid rents and obligatory services to the landlord, who was typically a nobleman. Peasant leaders supervised the fields and ditches and grazing rights, maintained public order and morals, and supported a village court which handled minor offenses. Inside the family, the patriarch made all the decisions and tried to arrange advantageous marriages for his children. Much of the villages' communal life centered around church services and holy days. In Prussia, the peasants drew lots to choose conscripts required by the army. The noblemen handled external relationships and politics for the villages under their control, and were not typically involved in daily activities or decisions.Rapidly growing cities

After 1815, the urban population grew rapidly, due primarily to the influx of young people from the rural areas.Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

grew from 172,000 people in 1800 to 826,000 in 1870; Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

grew from 130,000 to 290,000; Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

from 40,000 to 269,000; (now ) from 60,000 to 208,000; Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

from 60,000 to 177,000; (now Kaliningrad

Kaliningrad,. known as Königsberg; ; . until 1946, is the largest city and administrative centre of Kaliningrad Oblast, an Enclave and exclave, exclave of Russia between Lithuania and Poland ( west of the bulk of Russia), located on the Prego ...

) from 55,000 to 112,000. Offsetting this growth, there was extensive emigration, especially to the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. Emigration totaled 480,000 in the 1840s, 1,200,000 in the 1850s, and 780,000 in the 1860s.

Ethnic minorities

Despite its name and intention, the German Confederation was not entirely populated by Germans; many people of other ethnic groups lived within its borders: *French-speaking

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. Like all other Romance languages, it descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire. French evolved from Northern Old Gallo-Romance, a descendant of the Latin spoken in ...

Walloons

Walloons ( ; ; ) are a Gallo-Romance languages, Gallo-Romance ethnic group native to Wallonia and the immediate adjacent regions of Flanders, France, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. Walloons primarily speak ''langues d'oïl'' such as B ...

lived in western Luxembourg prior to its division in 1839;

* the Duchy of Limburg

The Duchy of Limburg or Limbourg was an imperial estate of the Holy Roman Empire. Much of the area of the duchy is today located within Liège Province of Belgium, with a small portion in the municipality of Voeren, an Enclave and exclave, excla ...

(a member between 1839 and 1866) had an entirely Dutch population;

* Italians

Italians (, ) are a European peoples, European ethnic group native to the Italian geographical region. Italians share a common Italian culture, culture, History of Italy, history, Cultural heritage, ancestry and Italian language, language. ...

and Slovenians

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, and History of Slove ...

lived in south and southeast Austria;

* Bohemia and Moravia, of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown

The Lands of the Bohemian Crown were the states in Central Europe during the Middle Ages, medieval and early modern periods with feudalism, feudal obligations to the List of Bohemian monarchs, Bohemian kings. The crown lands primarily consisted o ...

, were inhabited by a majority of Czechs

The Czechs (, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavs, West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common Bohemia ...

;

* Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

had also a Polish and Czech inhabitants, while Sorbs

Sorbs (; ; ; ; ; also known as Lusatians, Lusatian Serbs and Wends) are a West Slavs, West Slavic ethnic group predominantly inhabiting the parts of Lusatia located in the German states of Germany, states of Saxony and Brandenburg. Sorbs tradi ...

were present in the parts of Saxony

Saxony, officially the Free State of Saxony, is a landlocked state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, and Bavaria, as well as the countries of Poland and the Czech Republic. Its capital is Dresden, and ...

and the Prussian province of Brandenburg known as Lusatia

Lusatia (; ; ; ; ; ), otherwise known as Sorbia, is a region in Central Europe, formerly entirely in Germany and today territorially split between Germany and modern-day Poland. Lusatia stretches from the Bóbr and Kwisa rivers in the eas ...

* Prussian part of the partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partition (politics), partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place between 1772 and 1795, toward the end of the 18th century. They ended the existence of the state, resulting in the eli ...

was inhabited by a majority of Poles.

: economic integration

customs union

A customs union is generally defined as a type of trade bloc which is composed of a free trade area with a common external tariff.GATTArticle 24 s. 8 (a)

Customs unions are established through trade pacts where the participant countries set u ...

, the . In 1834, the Prussian regime sought to stimulate wider trade advantages and industrialism by decreea logical continuation of the program of and less than two decades earlier. Historians have seen three Prussian goals: as a political tool to eliminate Austrian influence in Germany; as a way to improve the economies; and to strengthen Germany against potential French aggression while reducing the economic independence of smaller states.

Inadvertently, these reforms sparked the unification movement and augmented a middle class demanding further political rights, but at the time backwardness and Prussia's fears of its stronger neighbors were greater concerns. The customs union opened up a common market, ended tariffs between states, and standardized weights, measures, and currencies within member states (excluding Austria), forming the basis of a proto-national economy.

By 1842 the included most German states. Within the next twenty years, the output of German furnaces increased fourfold. Coal production grew rapidly as well. In turn, German industry (especially the works established by the family) introduced the steel gun, cast-steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

axle

An axle or axletree is a central shaft for a rotation, rotating wheel and axle, wheel or gear. On wheeled vehicles, the axle may be fixed to the wheels, rotating with them, or fixed to the vehicle, with the wheels rotating around the axle. In ...

, and a breech-loading rifle, exemplifying Germany's successful application of technology to weaponry. Germany's security was greatly enhanced, leaving the Prussian state and the landowning aristocracy secure from outside threat. German manufacturers also produced heavily for the civilian sector. No longer would Britain supply half of Germany's needs for manufactured goods, as it did beforehand. However, by developing a strong industrial base, the Prussian state strengthened the middle class and thus the nationalist movement. Economic integration

Economic integration is the unification of economic policies between different states, through the partial or full abolition of tariff and Non-tariff barriers to trade, non-tariff restrictions on trade.

The trade-stimulation effects intended by ...

, especially increased national consciousness among the German states, made political unity a far likelier scenario. Germany finally began exhibiting all the features of a proto-nation.

The crucial factor enabling Prussia's conservative regime to survive the era was a rough coalition between leading sectors of the landed upper class and the emerging commercial and manufacturing interests. Even if the commercial and industrial element is weak, it must be strong enough (or soon become strong enough) to become worthy of co-optation, and the French Revolution terrified enough perceptive elements of Prussia's ''s'' for the state to be sufficiently accommodating.

While relative stability was maintained until 1848, with enough bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and Aristocracy (class), aristocracy. They are tradition ...

elements still content to exchange the "right to rule for the right to make money", the landed upper class found its economic base sinking. While the brought economic progress and helped to keep the bourgeoisie at bay for a while, it increased the ranks of the middle class swiftlythe very social base for the nationalism and liberalism that the Prussian state sought to stem.

The was a move toward economic integration, modern industrial capitalism, and the victory of centralism over localism, quickly bringing to an end the era of guilds in the small German princely states. This led to the 1844 revolt of the Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

n Weavers, who saw their livelihood destroyed by the flood of new manufactures.

The also weakened Austrian domination of the Confederation as economic unity increased the desire for political unity and nationalism.

Revolutions of 1848

News of the 1848 Revolution in Paris quickly reached discontented bourgeois liberals, republicans and more radical working-men. The first revolutionary uprisings in Germany began in the state of in March 1848. Within a few days, there were revolutionary uprisings in other states including Austria, and finally in Prussia. On 15 March 1848, the subjects of of Prussia vented their long-repressed political aspirations in violent rioting in Berlin, while barricades were erected in the streets of Paris. King of France fled to Great Britain. gave in to the popular fury, and promised aconstitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

, a parliament, and support for German unification, safeguarding his own rule and regime.

On 18 May, the Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt National Assembly () was the first freely elected parliament for all German Confederation, German states, including the German-populated areas of the Austrian Empire, elected on 1 May 1848 (see German federal election, 1848).

The ...

(Frankfurt Assembly) opened its first session, with delegates from various German states. It was immediately divided between those favoring a (small German) or (greater German) solution. The former favored offering the imperial crown to Prussia. The latter favored the Habsburg crown in Vienna, which would integrate Austria proper and Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

(but not Hungary) into the new Germany.

In May to August, the Assembly installed a provisional German Central Government, while conservatives swiftly moved against the reformers. As in Austria and Russia, this middle-class assertion increased authoritarian and reactionary sentiments among the landed upper class, whose economic position was declining. They turned to political levers to preserve their rule. As the Prussian army proved loyal, and the peasants were uninterested, regained his confidence. The Assembly belatedly issued its Declaration of the Rights of the German People; a constitution was drawn up (excluding Austria, which openly rejected the Assembly), and the leadership of the was offered to , who refused to "pick up a crown from the gutter". As the monarchist forces marched their armies to crush rebellions in cities and towns throughout Austria and Germany the Frankfurt Assembly was forced to flee, first to Stuttgart and then to Württemberg, where, reduced to so few deputies that it could no longer form a quorum, its final meeting was forcibly dispersed on 18 June 1849 by the Württemberg army. With the complete triumph of monarchist reaction rampaging across all of Europe, thousands of German middle class liberals and "red" Forty-eighters were forced to flee into exile (primarily to the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia).

In 1849, proposed his own constitution. His document concentrated real power in the hands of the King and the upper classes, and called for a confederation of North German statesthe Erfurt Union

The Erfurt Union () was a short-lived union of German states under a federation, proposed by the Kingdom of Prussia at Erfurt, for which the Erfurt Union Parliament (''Erfurter Unionsparlament''), officially lasting from March 20 to April 29, 1 ...

. Austria and Russia, fearing a strong, Prussian-dominated Germany, responded by pressuring Saxony and Hanover to withdraw, and forced Prussia to abandon the scheme in a treaty dubbed the " humiliation of ".

Dissolution of the Confederation

Rise of Bismarck

A new generation of statesmen responded to popular demands for national unity for their own ends, continuing Prussia's tradition of autocracy and reform from above. Germany found an able leader to accomplish the seemingly paradoxical task of conservative modernization. In 1851, Bismarck was appointed by KingWilhelm I

Wilhelm I (Wilhelm Friedrich Ludwig; 22 March 1797 – 9 March 1888) was King of Prussia from 1861 and German Emperor from 1871 until his death in 1888. A member of the House of Hohenzollern, he was the first head of state of a united Germany. ...

of Prussia (the future Kaiser Wilhelm I) to circumvent the liberals in the Landtag of Prussia

The Landtag of Prussia () was the representative assembly of the Kingdom of Prussia implemented in 1849, a bicameralism, bicameral legislature consisting of the upper Prussian House of Lords, House of Lords (''Herrenhaus'') and the lower Prussian ...

, who resisted Wilhelm's autocratic militarism. Bismarck told the Diet, "The great questions of the day are not decided by speeches and majority votes ... but by blood and iron" – that is, by warfare and industrial might. Prussia already had a great army; it was now augmented by rapid growth of economic power

Economic power refers to the ability of countries, businesses or individuals to make decisions on their own that benefit them. Scholars of international relations also refer to the economic power of a country as a factor influencing its power in ...

.

Gradually, Bismarck subdued the more restive elements of the middle class with a combination of threats and reforms, reacting to the revolutionary sentiments expressed in 1848 by providing them with the economic opportunities for which the urban middle sectors had been fighting.

Seven Weeks' War

The German Confederation ended as a result of theAustro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War (German: ''Preußisch-Österreichischer Krieg''), also known by many other names,Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Second War of Unification, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), ''Deutsc ...

of 1866 between the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

and its allies on one side and the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

and its allies on the other. The Confederation had 33 members immediately before its dissolution. In the Prague peace treaty, on 23 August 1866, Austria had to accept that the Confederation was dissolved. The following day, the remaining member states confirmed the dissolution. The treaty allowed Prussia to create a new (a new kind of federation) in the North of Germany. The South German states were allowed to create a South German Confederation but this did not come into existence.

North German Confederation

Prussia created theNorth German Confederation

The North German Confederation () was initially a German military alliance established in August 1866 under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was transformed in the subsequent year into a confederated state (a ''de facto'' feder ...

in 1867, a federal state combining all German states north of the river Main and also the Hohenzollern territories in Swabia

Swabia ; , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of Swabia, one of ...

. Besides Austria, the South German states Bavaria, , , and Hesse- remained separate from the rest of Germany. However, due to the successful prosecution of the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

, the four southern states joined the North German Confederation by treaties in November 1870.

German Empire

As the Franco-Prussian War drew to a close, King Ludwig II of Bavaria was persuaded to ask King Wilhelm to assume the crown of the new German Empire. On 1 January 1871, the Empire was declared by the presiding princes and generals in the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles, nearParis

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. The Diet of the North German Confederation moved to rename the North German Confederation as the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

and gave the title of German Emperor

The German Emperor (, ) was the official title of the head of state and Hereditary monarchy, hereditary ruler of the German Empire. A specifically chosen term, it was introduced with the 1 January 1871 constitution and lasted until the abdicati ...

to the King of Prussia. The new constitution of the state, the Constitution of the German Confederation, effectively transformed the Diet of the Confederation into the German Parliament (''Reichstag'').

Legacy

The modern German nation state known as the Federal Republic is the continuation of the North German Confederation of 1867. This North German Confederation, a federal state, was a totally new creation: the law of the German Confederation ended, and new law came into existence. The German Confederation was, according to historian Kotulla, an association of states ''(Staatenbund)'' with some elements of a federal state ''(Bundesstaat)'', and the North German Confederation was a federal state with some elements of an association of states.

Still, the discussions and ideas of the period 1815–66 had a huge influence on the constitution of the North German Confederation. Most notably may be the Federal Council, the organ representing the member states. It is a certain copy of the 1815 Federal Convention of the German Confederation. The successor of that Federal Council of 1867 is the modern Bundesrat of the Federal Republic.

The German Confederation does not play a very prominent role in German historiography and national culture. It is mainly seen negatively as an instrument to oppress the liberal, democratic and national movements of the period. On the contrary, the March revolution (1849/49) with its events and institutions attract much more attention and partially devotion. The most important memorial sites are the Paulskirche in Frankfurt, which is now a cultural hall of national importance, and the Rastatt castle with the '' Erinnerungsstätte für die Freiheitsbewegungen in der deutschen Geschichte'' (a museum and memorial site for the freedom movements in the German history, not only the March revolution).

The remnants of the federal fortifications are certain tourists attractions at least regionally or for people interested in military history.

The modern German nation state known as the Federal Republic is the continuation of the North German Confederation of 1867. This North German Confederation, a federal state, was a totally new creation: the law of the German Confederation ended, and new law came into existence. The German Confederation was, according to historian Kotulla, an association of states ''(Staatenbund)'' with some elements of a federal state ''(Bundesstaat)'', and the North German Confederation was a federal state with some elements of an association of states.

Still, the discussions and ideas of the period 1815–66 had a huge influence on the constitution of the North German Confederation. Most notably may be the Federal Council, the organ representing the member states. It is a certain copy of the 1815 Federal Convention of the German Confederation. The successor of that Federal Council of 1867 is the modern Bundesrat of the Federal Republic.

The German Confederation does not play a very prominent role in German historiography and national culture. It is mainly seen negatively as an instrument to oppress the liberal, democratic and national movements of the period. On the contrary, the March revolution (1849/49) with its events and institutions attract much more attention and partially devotion. The most important memorial sites are the Paulskirche in Frankfurt, which is now a cultural hall of national importance, and the Rastatt castle with the '' Erinnerungsstätte für die Freiheitsbewegungen in der deutschen Geschichte'' (a museum and memorial site for the freedom movements in the German history, not only the March revolution).

The remnants of the federal fortifications are certain tourists attractions at least regionally or for people interested in military history.

Territorial legacy

The current countries whose territory were partly or entirely located inside the boundaries of the German Confederation 1815–1866 are: * Germany (allstates

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

except Southern in the north of )

* Austria (all states

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

except )

* Luxembourg

Luxembourg, officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France on the south. Its capital and most populous city, Luxembour ...

(entire territory)

* Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (, ; ; ), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein ( ), is a Landlocked country#Doubly landlocked, doubly landlocked Swiss Standard German, German-speaking microstate in the Central European Alps, between Austria in the east ...

(entire territory)

* Netherlands (Duchy of Limburg

The Duchy of Limburg or Limbourg was an imperial estate of the Holy Roman Empire. Much of the area of the duchy is today located within Liège Province of Belgium, with a small portion in the municipality of Voeren, an Enclave and exclave, excla ...

, was a member of the Confederation from 1839 until 1866)

* Czech Republic (entire territory)

* Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

(except for and the municipalities of , and )

* Poland ( West Pomeranian Voivodship, Voivodship, Lower Silesian Voivodship, Voivodship, part of Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

– overwhelmingly German speaking at the time; East Prussia

East Prussia was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871); following World War I it formed part of the Weimar Republic's ...

, West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (; ; ) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and from 1878 to 1919. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1773, formed from Royal Prussia of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonweal ...