Decapitation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Decapitation is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and all vertebrate animals, since it deprives the brain of

Humans have practiced

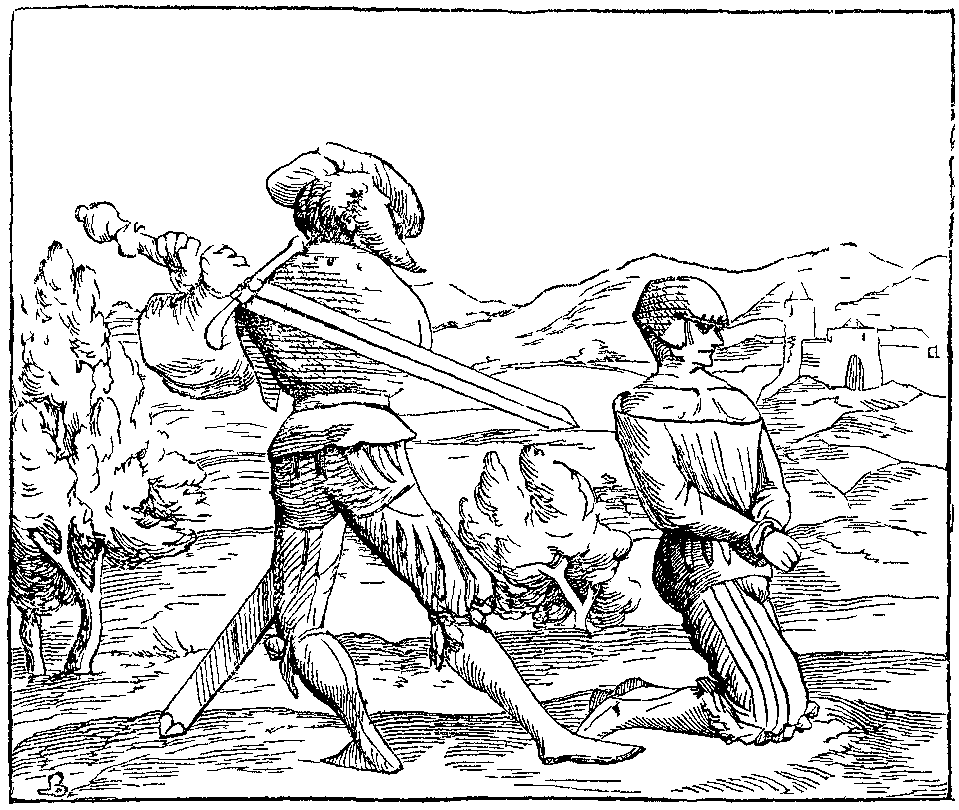

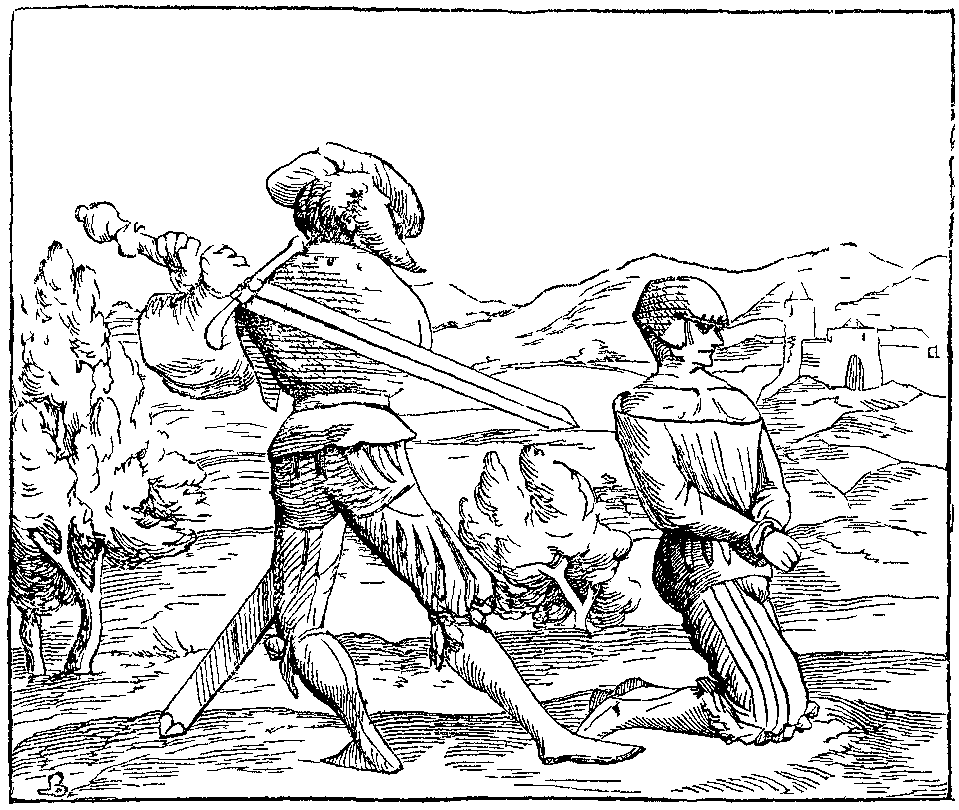

Humans have practiced  To ensure that the blow would be fatal, executioners' swords usually were blade-heavy two-handed swords. Likewise, if an axe was used, it almost invariably was wielded with both hands.

To ensure that the blow would be fatal, executioners' swords usually were blade-heavy two-handed swords. Likewise, if an axe was used, it almost invariably was wielded with both hands.

Many German states had used a

Many German states had used a

In traditional

In traditional

In

In

In

In

The ancient Greeks and Romans regarded decapitation as a comparatively honorable form of execution for criminals. The traditional procedure, however, included first being tied to a stake and whipped with rods. Axes were used by the Romans, and later swords, which were considered a more honorable instrument of death. Those who could verify that they were Roman citizens were to be beheaded, rather than undergoing

The ancient Greeks and Romans regarded decapitation as a comparatively honorable form of execution for criminals. The traditional procedure, however, included first being tied to a stake and whipped with rods. Axes were used by the Romans, and later swords, which were considered a more honorable instrument of death. Those who could verify that they were Roman citizens were to be beheaded, rather than undergoing

Crime Library

(archived)

{{Capital punishment Capital punishment Causes of death Execution methods

oxygenated blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the Cell (biology), cells, and transports Metabolic waste, metabolic waste products away from th ...

by way of severing through the jugular vein

The jugular veins () are veins that take blood from the head back to the heart via the superior vena cava. The internal jugular vein descends next to the internal carotid artery and continues posteriorly to the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Struc ...

and common carotid artery

In anatomy, the left and right common carotid arteries (carotids) () are artery, arteries that supply the head and neck with oxygenated blood; they divide in the neck to form the external carotid artery, external and internal carotid artery, inte ...

, while all other organs are deprived of the involuntary functions that are needed for the body to function.

The term beheading refers to the act of deliberately decapitating a person, either as a means of murder or as an execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in ...

; it may be performed with an axe

An axe (; sometimes spelled ax in American English; American and British English spelling differences#Miscellaneous spelling differences, see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for thousands of years to shape, split, a ...

, sword

A sword is an edged and bladed weapons, edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter ...

, or knife

A knife (: knives; from Old Norse 'knife, dirk') is a tool or weapon with a cutting edge or blade, usually attached to a handle or hilt. One of the earliest tools used by humanity, knives appeared at least Stone Age, 2.5 million years ago, as e ...

, or by mechanical means such as a guillotine

A guillotine ( ) is an apparatus designed for effectively carrying out executions by Decapitation, beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secur ...

. An executioner

An executioner, also known as a hangman or headsman, is an official who effects a sentence of capital punishment on a condemned person.

Scope and job

The executioner was usually presented with a warrant authorizing or ordering him to ...

who carries out executions by beheading is sometimes called a headsman. Accidental decapitation can be the result of an explosion, a car or industrial accident, improperly administered execution by hanging

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

or other violent injury. The national laws of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

and Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

permit beheading. Under Sharia

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

, which exclusively applies to Muslims, beheading is also a legal punishment in Zamfara State

Zamfara (; ; Adlam script, Adlam: ) is a States of Nigeria, state in northwestern Nigeria. The capital of Zamfara state is Gusau and its current List of Governors of Zamfara State, governor is Dauda Lawal. Until 1996, the area was part of Soko ...

, Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

. In practice, Saudi Arabia is the only country that continues to behead its offenders regularly as a punishment for capital crimes. Cases of decapitation by suicidal hanging, suicide by train decapitation

Rail suicide is deliberate self-harm resulting in death by means of a moving rail vehicle. The suicide occurs when an approaching train hits a suicidal pedestrian jumping onto, lying down on, or wandering or standing on the tracks. Low friction o ...

and by guillotine are known.

Less commonly, decapitation can also refer to the removal of the head from a body that is already dead. This might be done to take the head as a trophy

A trophy is a tangible, decorative item used to remind of a specific achievement, serving as recognition or evidence of merit. Trophies are most commonly awarded for sports, sporting events, ranging from youth sports to professional level athlet ...

, as a secondary stage of an execution by hanging, for public display, to make the deceased more difficult to identify, for cryonics

Cryonics (from ''kryos'', meaning "cold") is the low-temperature freezing (usually at ) and storage of human remains in the hope that resurrection may be possible in the future. Cryonics is regarded with skepticism by the mainstream scien ...

, or for other, more esoteric reasons.

Etymology

The word decapitation has its roots in the Late Latin word . The meaning of the word can be discerned from its morphemes (down, from) + (head). The past participle of is which was used to create , the noun form of , in Medieval Latin, whence the French word was produced.History

Humans have practiced

Humans have practiced capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

by beheading for millennia. The Narmer Palette

The Narmer Palette, also known as the Great Hierakonpolis Palette or the Palette of Narmer, is a significant Egyptian archaeological find, dating from about the 31st century BC, belonging, at least nominally, to the category of cosmetic palettes ...

(c. 3000 BCE) shows the first known depiction of decapitated corpses. The terms "capital offence", "capital crime", "capital punishment", derive from the Latin , "head", referring to the punishment for serious offences involving the forfeiture of the head; i.e. death by beheading.

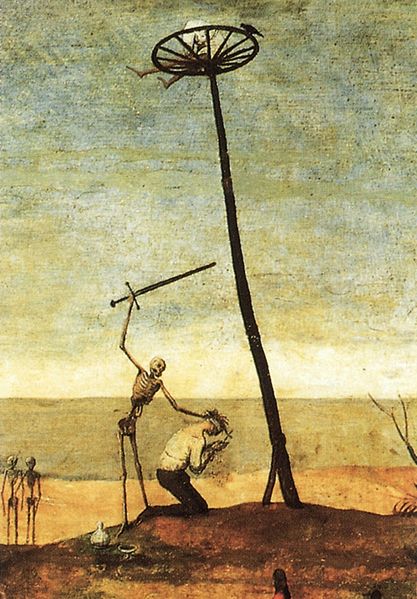

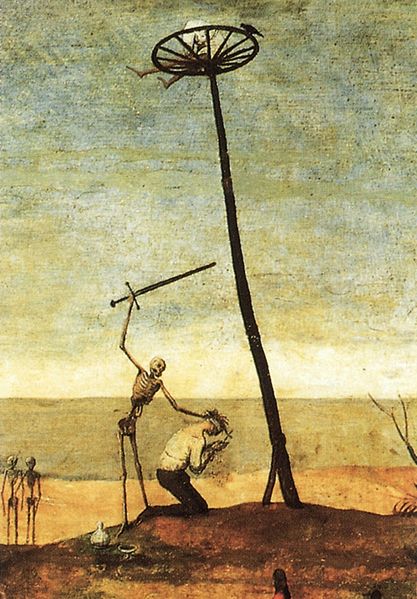

Some cultures, such as ancient Rome and Greece, regarded decapitation as the most honorable form of death. In the Middle Ages, many European nations continued to reserve the method only for nobles and royalty. In France, the French Revolution made it the only legal method of execution for all criminals regardless of class, one of the period's many symbolic changes.

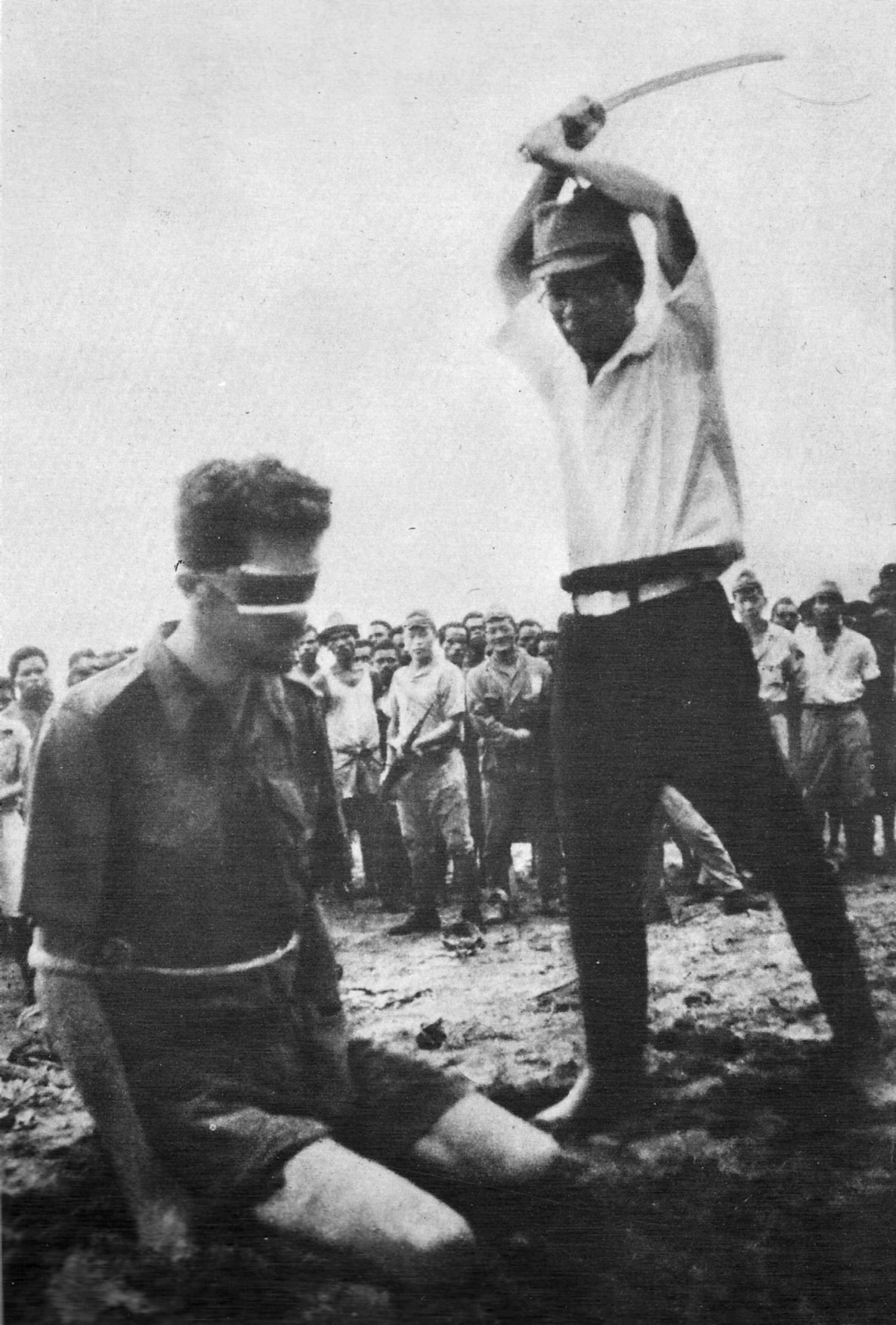

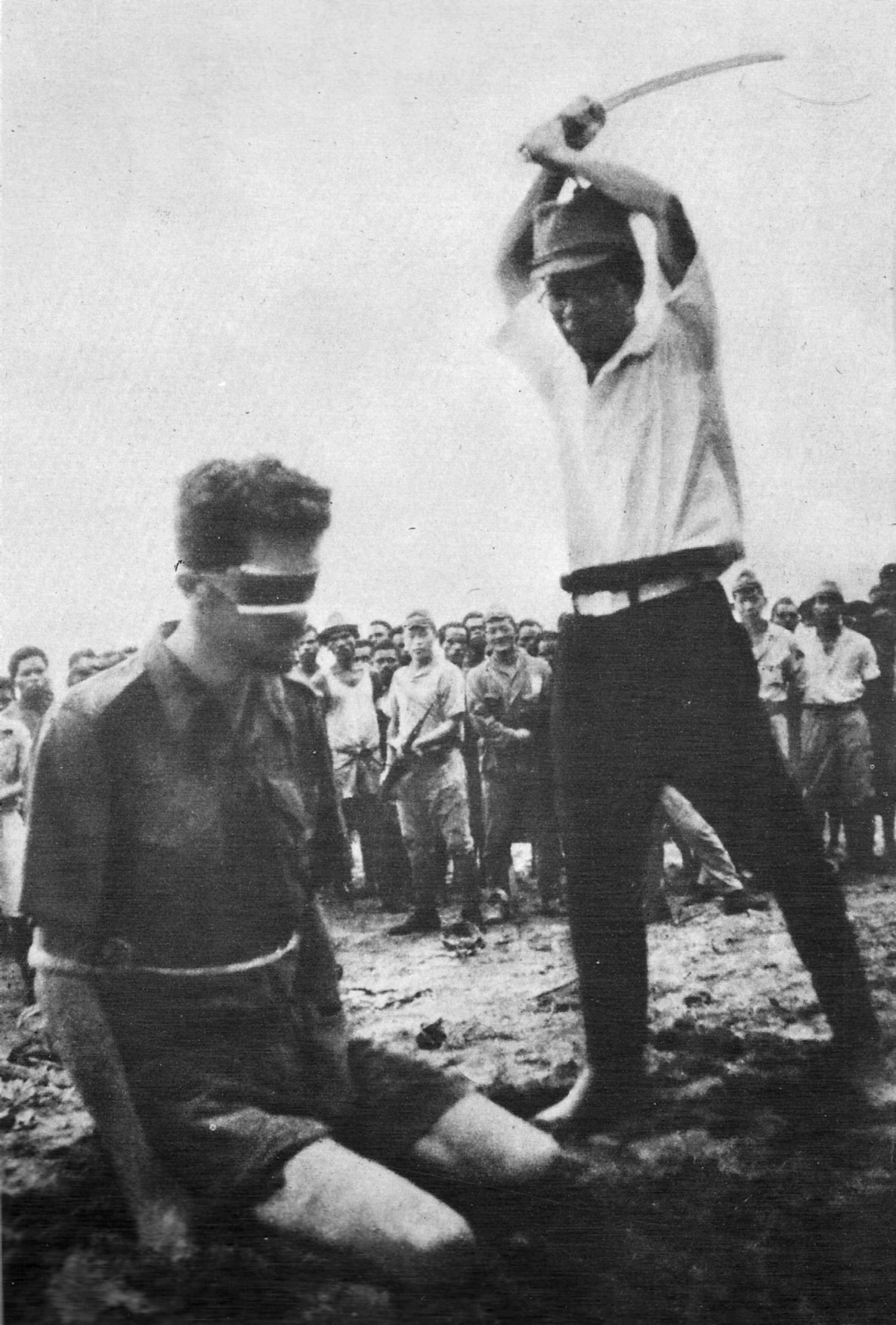

Others have regarded beheading as dishonorable and contemptuous, such as the Japanese troops who beheaded prisoners during World War II. In recent times, it has become associated with terrorism.

If a headsman's axe

An axe (; sometimes spelled ax in American English; American and British English spelling differences#Miscellaneous spelling differences, see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for thousands of years to shape, split, a ...

or sword

A sword is an edged and bladed weapons, edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter ...

is sharp and his aim is precise, decapitation is quick and thought to be a relatively painless form of death

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose sh ...

. If the instrument is blunt or the executioner is clumsy, repeated strokes might be required to sever the head, resulting in a prolonged and more painful death. Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex (; 10 November 1565 – 25 February 1601) was an English nobleman and a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. Politically ambitious, he was placed under house arrest following a poor campaign in Ireland during th ...

, and Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

required three strikes at their respective executions. The same could be said for the execution of Johann Friedrich Struensee

Count, Lensgreve Johann Friedrich Struensee (5 August 1737 – 28 April 1772) was a German-Danish physician, philosopher and statesman. He became royal physician to the mentally ill King Christian VII of Denmark and a minister in the Danish gov ...

, favorite of the Danish queen Caroline Matilda of Great Britain. Margaret Pole, 8th Countess of Salisbury, is said to have required up to 10 strokes before decapitation was achieved. This particular story may, however, be apocryphal, as highly divergent accounts exist. Historian and philosopher David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

, for example, relates the following about her death: To ensure that the blow would be fatal, executioners' swords usually were blade-heavy two-handed swords. Likewise, if an axe was used, it almost invariably was wielded with both hands.

To ensure that the blow would be fatal, executioners' swords usually were blade-heavy two-handed swords. Likewise, if an axe was used, it almost invariably was wielded with both hands.

Physiological aspects

Physiology of death by decapitation

Decapitation is quickly fatal tohumans

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

and most animals

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, have myocytes and are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and grow from a ...

. Unconsciousness occurs within seconds without circulating oxygenated blood (brain ischemia

Brain ischemia is a condition in which there is insufficient bloodflow to the brain to meet metabolic demand. This leads to cerebral hypoxia, poor oxygen supply in the brain and may be temporary such as in transient ischemic attack or permanent i ...

). Cell death and irreversible brain damage

Brain injury (BI) is the destruction or degeneration of brain cells. Brain injuries occur due to a wide range of internal and external factors. In general, brain damage refers to significant, undiscriminating trauma-induced damage.

A common ...

occurs after 3–6 minutes with no oxygen, due to excitotoxicity

In excitotoxicity, neuron, nerve cells suffer damage or death when the levels of otherwise necessary and safe neurotransmitters such as glutamic acid, glutamate become pathologically high, resulting in excessive stimulation of cell surface recept ...

. Some anecdotes suggest more extended persistence of human consciousness after decapitation, but most doctors consider this unlikely and consider such accounts to be misapprehensions of reflexive twitching rather than deliberate movement, since deprivation of oxygen must cause nearly immediate coma and death (" onsciousness isprobably lost within 2–3 seconds, due to a rapid fall of intracranial perfusion

Perfusion is the passage of fluid through the circulatory system or lymphatic system to an organ (anatomy), organ or a tissue (biology), tissue, usually referring to the delivery of blood to a capillary bed in tissue. Perfusion may also refer t ...

of blood").

A laboratory study testing for humane methods of euthanasia in awake animals used EEG monitoring to measure the time duration following decapitation for rats to become fully unconscious, unable to perceive distress and pain. It was estimated that this point was reached within 3–4 seconds, correlating closely with results found in other studies on rodents (2.7 seconds, and 3–6 seconds). The same study also suggested that the massive wave which can be recorded by EEG monitoring approximately one minute after decapitation ultimately reflects brain death. Other studies indicate that electrical activity in the brain has been demonstrated to persist for 13 to 14 seconds following decapitation (although it is disputed as to whether such activity implies that pain is perceived), and a 2010 study reported that decapitation of rats generated responses in EEG indices over a period of 10 seconds that have been linked to nociception

In physiology, nociception , also nocioception; ) is the Somatosensory system, sensory nervous system's process of encoding Noxious stimulus, noxious stimuli. It deals with a series of events and processes required for an organism to receive a pai ...

across a number of different species of animals, including rats.

Some animals (such as cockroach

Cockroaches (or roaches) are insects belonging to the Order (biology), order Blattodea (Blattaria). About 30 cockroach species out of 4,600 are associated with human habitats. Some species are well-known Pest (organism), pests.

Modern cockro ...

es) can survive decapitation and die not because of the loss of the head directly, but rather because of starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, de ...

. A number of other animals, including snake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

s, and turtle

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

s, have also been known to survive for some time after being decapitated, as they have slower metabolisms and their nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its behavior, actions and sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its body. Th ...

s can continue to function at some capacity for a limited time even after connection to the brain is lost, responding to any nearby stimulus. In addition, the bodies of chicken

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domesticated subspecies of the red junglefowl (''Gallus gallus''), originally native to Southeast Asia. It was first domesticated around 8,000 years ago and is now one of the most common and w ...

s and turtles may continue to move temporarily after decapitation.

Although head transplantation by the reattachment of blood vessels has seen some very limited success in animals, a fully functional reattachment of a severed human head (including repair of the spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue that extends from the medulla oblongata in the lower brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone) of vertebrate animals. The center of the spinal c ...

, muscles, and other critically important tissues) has not yet been achieved.

Technology

Guillotine

Early versions of the guillotine included theHalifax Gibbet

The Halifax Gibbet was an early guillotine used in the town of Halifax, West Yorkshire, England. Estimated to have been installed during the 16th century, it was used as an alternative to beheading by axe or sword. Halifax was once part of ...

, which was used in Halifax, England, from 1286 until the 17th century, and the " Maiden", employed in Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

from the 16th through the 18th centuries.

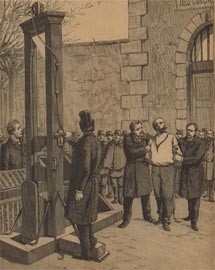

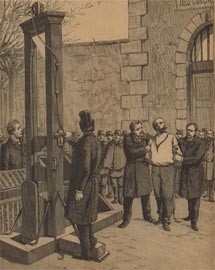

The modern form of the guillotine

A guillotine ( ) is an apparatus designed for effectively carrying out executions by Decapitation, beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secur ...

was invented shortly before the French Revolution with the aim of creating a quick and painless method of execution requiring little skill on the part of the operator. Decapitation by guillotine became a common mechanically assisted form of execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in ...

.

The French observed a strict code of etiquette surrounding such executions. For example, a man named Legros, one of the assistants at the execution of Charlotte Corday

Marie-Anne Charlotte de Corday d'Armont (27 July 1768 – 17 July 1793), known simply as Charlotte Corday (), was a figure of the French Revolution who assassinated revolutionary and Jacobins, Jacobin leader Jean-Paul Marat on 13 July 1793. Cor ...

, was imprisoned for three months and dismissed for slapping the face of the victim after the blade had fallen in order to see whether any flicker of life remained. The guillotine was used in France during the French Revolution and remained the normal judicial method in both peacetime and wartime into the 1970s, although the firing squad

Firing may refer to:

* Dismissal (employment), sudden loss of employment by termination

* Firemaking, the act of starting a fire

* Burning; see combustion

* Shooting, specifically the discharge of firearms

* Execution by firing squad, a method of ...

was used in certain cases. France abolished the death penalty in 1981.

The guillotine was also used in Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

before the French relinquished control of it, as shown in Gillo Pontecorvo

Gilberto Pontecorvo (; 19 November 1919 – 12 October 2006) was an Italian filmmaker associated with the political cinema movement of the 1960s and 1970s. He is best known for directing the landmark war docudrama '' The Battle of Algiers'' (19 ...

's film '' The Battle of Algiers''.

Many German states had used a

Many German states had used a guillotine

A guillotine ( ) is an apparatus designed for effectively carrying out executions by Decapitation, beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secur ...

-like device known as a ("falling axe") since the 17th and 18th centuries, and decapitation by guillotine was the usual means of execution in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

until the abolition of the death penalty in West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

in 1949. It was last used in communist East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

in 1966.

In Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, the was reserved for common criminals and people convicted of political crime

In criminology, a political crime or political offence is an offence that prejudices the interests of the state or its government. States may criminalise any behaviour perceived as a threat, real or imagined, to the state's survival, including ...

s, including treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

. Members of the White Rose

The White Rose (, ) was a Nonviolence, non-violent, intellectual German resistance to Nazism, resistance group in Nazi Germany which was led by five students and one professor at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, University of Munich ...

resistance movement, a group of students in Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

that included siblings Sophie

Sophie is a feminine given name, another version of Sophia, from the Greek word for "wisdom".

People with the name Born in the Middle Ages

* Sophie, Countess of Bar (c. 1004 or 1018–1093), sovereign Countess of Bar and lady of Mousson

* Soph ...

and Hans Scholl, were executed by decapitation.

Contrary to popular myth, executions were generally not conducted face-up, and chief executioner Johann Reichhart was insistent on maintaining "professional" protocol throughout the era, having administered the death penalty during the earlier Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

. Nonetheless, it is estimated that some 16,500 persons were guillotined in Germany and Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

between 1933 and 1945, a number that includes resistance fighters both within Germany itself and in countries occupied by Nazi forces. As these resistance fighters were not part of any regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a ...

, they were considered common criminals and were in many cases transported

''Transported'' is an Australian convict melodrama film directed by W. J. Lincoln.

It is considered a lost film.

Plot

In England, Jessie Grey is about to marry Leonard Lincoln but the evil Harold Hawk tries to force her to marry him and she ...

to Germany for execution. Decapitation was considered a "dishonorable" death, in contrast to execution by firing squad

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French , rifle), is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearms are usually rea ...

.

Historical practices by nation

Africa

Congo

In theDemocratic Republic of Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), also known as the DR Congo, Congo-Kinshasa, or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Republic of the Congo), is a country in Central Africa. By land area, it is t ...

, the conflict and ethnic massacre between local army and Kamuina Nsapu rebels has caused several deaths and atrocities such as rape and mutilation. One of them is decapitation, both a fearsome way to intimidate victims as well as an act that may include ritualistic elements. According to a UN report from Congolese refugees, they believed the Bana Mura and Kamuina Nsapu militias have "magical powers" as a result of drinking the blood of decapitated victims, making them invincible.

Besides the massive decapitations (like the beheading of 40 members of the State Police), a globally notorious case happened in March 2017 to Swedish politician Zaida Catalán and American UN expert Michael Sharp, who were kidnapped and executed during a mission near the village of Ngombe in Kasaï Province. The UN was reportedly horrified when video footage of the executions surfaced in April that same year, where some grisly details led to assume ritual components of the beheading: the perpetrators first cut the hair of both victims, and then one of them beheaded Catalán only, because it would "increase his power", which may be linked to the fact that Congolese militias are particularly brutal in their acts of violence toward women and children.

In the trial that followed investigations after the bodies were discovered, and according to a testimony of a primary school teacher from Bunkonde, near the village of Moyo Musuila where the executions took place, he witnessed a teenage militant carrying the young woman's head, but despite the efforts of the investigation, the head was never found. According to a report published on 29 May 2019, the Monusco peacekeeping military mission led by Colonel Luis Mangini, in the search for the missing remains, arrived to a ritual place in Moyo Musila where "parts of bodies, hands and heads" were cut and used for rituals, where they lost track of the victim's head.

Asia

Azerbaijan

During the 2016 Armenian–Azerbaijani clashes, Yazidi-Armenian serviceman Kyaram Sloyan was decapitated by Azerbaijani servicemen. Several reports of decapitation, along with other types of mutilation of Armenian POWs by Azerbaijani soldiers, emerged in 2020 during theSecond Nagorno-Karabakh War

The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War was an armed conflict in 2020 that took place in the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh and the Armenian-occupied territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh, surrounding occupied territories. It was a major esca ...

.

China

In traditional

In traditional China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, decapitation was considered a more severe form of punishment than strangulation

Strangling or strangulation is compression of the neck that may lead to unconsciousness or death by causing an increasingly hypoxic state in the brain by restricting the flow of oxygen through the trachea. Fatal strangulation typically occurs ...

, although strangulation caused more prolonged suffering. This was because in Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Founded by Confucius ...

tradition, a person's body was a gift from their parents, and so it was therefore disrespectful to their ancestors to return their bodies to the grave dismembered. The Chinese, however, had other punishments, such as dismembering the body into multiple pieces (similar to the English quartering). In addition, there was also a practice of cutting the body at the waist, which was a common method of execution before being abolished in the early Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

due to the lingering death it caused. In some tales, people did not die immediately after decapitation.

India

The British officer John Masters recorded in his autobiography that Pathans in British India during the Anglo-Afghan Wars would behead enemy soldiers who were captured, such as British and Sikh soldiers. TheExecution of Sambhaji

Sambhaji, the second Maratha king, was put to death by order of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in the 17th-century. The conflicts between the Mughals and the Deccan Sultanates, which resulted in the downfall of the Sultanates, paved the way for t ...

was a significant event in 17th-century Deccan

The Deccan is a plateau extending over an area of and occupies the majority of the Indian peninsula. It stretches from the Satpura and Vindhya Ranges in the north to the northern fringes of Tamil Nadu in the south. It is bound by the mount ...

India, where the second Maratha

The Marathi people (; Marathi: , ''Marāṭhī lōk'') or Marathis (Marathi: मराठी, ''Marāṭhī'') are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group who are native to Maharashtra in western India. They natively speak Marathi, an Indo-A ...

King was put to death by order of the Mughal emperor

The emperors of the Mughal Empire, who were all members of the Timurid dynasty (House of Babur), ruled the empire from its inception on 21 April 1526 to its dissolution on 21 September 1857. They were supreme monarchs of the Mughal Empire in ...

Aurangzeb

Alamgir I (Muhi al-Din Muhammad; 3 November 1618 – 3 March 1707), commonly known by the title Aurangzeb, also called Aurangzeb the Conqueror, was the sixth Mughal emperors, Mughal emperor, reigning from 1658 until his death in 1707, becomi ...

. The conflicts between the Mughals

The Mughal Empire was an early modern empire in South Asia. At its peak, the empire stretched from the outer fringes of the Indus River Basin in the west, northern Afghanistan in the northwest, and Kashmir in the north, to the highlands of pre ...

and the Deccan Sultanates

The Deccan sultanates is a historiographical term referring to five late medieval to early modern Persianate Indian Muslim kingdoms on the Deccan Plateau between the Krishna River and the Vindhya Range. They were created from the disintegrati ...

, which resulted in the downfall of the Sultanates, paved the way for tensions between the Marathas and the Mughals. Aurangzeb was drawn to Southern India due to the vanquished rebel Akbar

Akbar (Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar, – ), popularly known as Akbar the Great, was the third Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Akbar succeeded his father, Humayun, under a regent, Bairam Khan, who helped the young emperor expa ...

fleeing to the Maratha monarch, Sambhaji

Sambhaji (Sambhajiraje Shivajiraje Bhonsle, ; 14 May 1657 – 11 March 1689), also known as Shambhuraje, ruled from 1681 to 1689 as the second king ( Chhatrapati) of the Maratha Empire, a prominent state in early modern India. He was the elde ...

. The Maratha King was then captured by the Mughal general Muqarrab Khan

Muqarrab Khan of Golconda, also known as Khan Zaman Fath Jang Dakhini, was an Indian Deccani Muslim military personnel, who was the most experienced commander of Qutb Shahi Dynasty, during the reign of Abul Hasan Qutb Shah. He is known for betr ...

. Sambhaji and his minister Kavi Kalash were then taken to Tulapur

Tulapur is a village in Pune district, Maharashtra, India, associated with the last execution of Sambhaji, second Chatrapati and son of Shivaji.

Etymology

Tulapur village was originally known as Nagargaon. It was renamed Tulapur when Shahaji ...

, where they were tortured to death.

Japan

In

In Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, decapitation was a common punishment, sometimes for minor offences. Samurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

were often allowed to decapitate soldiers who had fled from battle, as it was considered cowardly. Decapitation was historically performed as the second step in seppuku

, also known as , is a form of Japanese ritualistic suicide by disembowelment. It was originally reserved for samurai in their code of honor, but was also practiced by other Japanese people during the Shōwa era (particularly officers near ...

(ritual suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death.

Risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse. Some suicides are impulsive acts driven by stress (such as from financial or ac ...

by disembowelment

Disembowelment, disemboweling, evisceration, eviscerating or gutting is the removal of Organ (biology), organs from the gastrointestinal tract (bowels or viscera), usually through an incision made across the Abdomen, abdominal area. Disembowelm ...

). After the victim had sliced his own abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the gut, belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach) is the front part of the torso between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and in other vertebrates. The area occupied by the abdomen is called the abdominal ...

open, another warrior would strike his head off from behind with a katana

A is a Japanese sword characterized by a curved, single-edged blade with a circular or squared guard and long grip to accommodate two hands. Developed later than the ''tachi'', it was used by samurai in feudal Japan and worn with the edge fa ...

to hasten death and to reduce the suffering. The blow was expected to be precise enough to leave intact a small strip of skin at the front of the neck—to spare invited and honored guests the indelicacy of witnessing a severed head rolling about, or towards them; such an occurrence would have been considered inelegant and in bad taste. The sword was expected to be used upon the slightest sign that the practitioner might yield to pain and cry out—avoiding dishonor to him and to all partaking in the privilege of observing an honorable demise. As skill was involved, only the most trusted warrior was honored by taking part. In the late Sengoku period

The was the period in History of Japan, Japanese history in which civil wars and social upheavals took place almost continuously in the 15th and 16th centuries. The Kyōtoku incident (1454), Ōnin War (1467), or (1493) are generally chosen as th ...

, decapitation was performed as soon as the person chosen to carry out seppuku had made the slightest wound to his abdomen.

Decapitation (without seppuku) was also considered a very severe and degrading form of punishment. One of the most brutal decapitations was that of (杉谷善住坊), who attempted to assassinate Oda Nobunaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods. He was the and regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan. He is sometimes referred as the "Demon Daimyō" and "Demo ...

, a prominent ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji era, Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and no ...

'', in 1570. After being caught, Zenjubō was buried alive in the ground with only his head out, and the head was slowly sawn off with a bamboo saw by passers-by for several days (punishment by sawing; (). These unusual punishments were abolished in the early Meiji era. A similar scene is described in the last page of James Clavell's book ''Shōgun''.

Korea

Historically, decapitation had been the most common method of execution in Korea, until it was replaced byhanging

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

in 1896. Professional executioners were called (망나니) and they were volunteered from death rows.

Thailand

Decapitation was the main method of execution in Thailand, until it was replaced byshooting

Shooting is the act or process of discharging a projectile from a ranged weapon (such as a gun, bow, crossbow, slingshot, or blowpipe). Even the acts of launching flame, artillery, darts, harpoons, grenades, rockets, and guided missile ...

in 1934.

Vietnam

Execution by beheading was one of the most common forms of execution in Vietnam under the feudal system. This form of execution still existed in theSouth Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam (RVN; , VNCH), was a country in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975. It first garnered Diplomatic recognition, international recognition in 1949 as the State of Vietnam within the ...

regime until 1962.

Europe

Bosnia and Herzegovina

During the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992–1995) there were a number of ritual beheadings of Serbs and Croats who were taken as prisoners of war bymujahideen

''Mujahideen'', or ''Mujahidin'' (), is the plural form of ''mujahid'' (), an Arabic term that broadly refers to people who engage in ''jihad'' (), interpreted in a jurisprudence of Islam as the fight on behalf of God, religion or the commun ...

members of the Bosnian Army. At least one case is documented and proven in court by the ICTY

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was a body of the United Nations that was established to prosecute the war crimes that had been committed during the Yugoslav Wars and to try their perpetrators. The tribun ...

where mujahedin, members of 3rd Corps of Army BiH, beheaded Bosnian Serb

The Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sr-Cyrl, Срби Босне и Херцеговине, Srbi Bosne i Hercegovine), often referred to as Bosnian Serbs ( sr-cyrl, босански Срби, bosanski Srbi) or Herzegovinian Serbs ( sr-cyrl, � ...

Dragan Popović.

Britain

In

In British history

The history of the British Isles began with its sporadic human habitation during the Palaeolithic from around 900,000 years ago. The British Isles has been continually occupied since the early Holocene, the current geological epoch, which star ...

, beheading was typically used for noblemen, while commoners would be hanged; eventually, hanging was adopted as the standard means of non-military executions. The last actual execution by beheading was of Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat

Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat, ( 1667 – 9 April 1747) was a Scottish landowner and head of Clan Fraser of Lovat. Convicted of high treason in the United Kingdom, high treason for his role in the Jacobite rising of 1745, he was the last ma ...

on 9 April 1747, while a number of convicts were beheaded posthumously up to the early 19th century. (Typically traitors were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered was a method of torture, torturous capital punishment used principally to execute men convicted of High treason in the United Kingdom, high treason in medieval and early modern Britain and Ireland. The convi ...

, a method which had already been discontinued.) Beheading was degraded to a secondary means of execution, including for treason, with the abolition of drawing and quartering in 1870 and finally abolished by the Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1973. One of the most notable executions by decapitation in Britain was that of King Charles I of England

Charles I (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649.

Charles was born into the House of Stuart as the second son of King James VI of Scotland, but after h ...

, who was beheaded

Decapitation is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and all vertebrate animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood by way of severing through the jugular vein and common c ...

outside the Banqueting House

The Banqueting House, on Whitehall in the City of Westminster, central London, is the grandest and best-known survivor of the architectural genre of banqueting houses, constructed for elaborate entertaining. It is the only large surviving comp ...

in Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

in 1649, after being captured by parliamentarians during the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

and tried for treason.

In England, a bearded axe was used for beheading, with the blade's edge extending downwards from the tip of the shaft.

Celts

TheCelts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

of western Europe long pursued a "cult of the severed head", as evidenced by both Classical literary descriptions and archaeological contexts. This cult played a central role in their temples and religious practices and earned them a reputation as head hunters

''Head Hunters'' is the twelfth studio album by American pianist, keyboardist and composer Herbie Hancock, released October 26, 1973, on Columbia Records. Recording sessions for the album took place in the evening at Wally Heider Studios and D ...

among the Mediterranean peoples. Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

, in his 1st-century ''Historical Library

''Bibliotheca historica'' (, ) is a work of universal history by Diodorus Siculus. It consisted of forty books, which were divided into three sections. The first six books are geographical in theme, and describe the history and culture of Egypt ...

'' (5.29.4) wrote the following about Celtic head-hunting:

Both the Greeks and Romans found the Celtic decapitation practices shocking and the latter put an end to them when Celtic regions came under their control.

According to Paul Jacobsthal, "Amongst the Celts the human head

In human anatomy, the head is at the top of the human body. It supports the face and is maintained by the human skull, skull, which itself encloses the human brain, brain.

Structure

The human head consists of a fleshy outer portion, which s ...

was venerated above all else, since the head was to the Celt the soul, centre of the emotions as well as of life itself, a symbol of divinity and of the powers of the other-world." Arguments for a Celtic cult of the severed head include the many sculptured representations of severed heads in La Tène carvings, and the surviving Celtic mythology, which is full of stories of the severed heads of heroes and the saints who carry their own severed heads, right down to ''Sir Gawain and the Green Knight'', where the Green Knight picks up his own severed head after Gawain has struck it off in a beheading game, just as Saint Denis carried his head to the top of Montmartre

Montmartre ( , , ) is a large hill in Paris's northern 18th arrondissement of Paris, 18th arrondissement. It is high and gives its name to the surrounding district, part of the Rive Droite, Right Bank. Montmartre is primarily known for its a ...

.Wilhelm, James J. "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." The Romance of Arthur. Ed. Wilhelm, James J. New York: Garland Publishing, 1994. 399–465.

A further example of this regeneration after beheading lies in the tales of Connemara

Connemara ( ; ) is a region on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of western County Galway, in the west of Ireland. The area has a strong association with traditional Irish culture and contains much of the Connacht Irish-speaking Gaeltacht, ...

's Saint Féchín, who after being beheaded by Vikings

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

carried his head to the Holy Well on Omey Island

Omey Island () is a tidal island situated near Claddaghduff on the western edge of Connemara in County Galway, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. From the mainland the island is almost hidden. It is possible to drive or walk across a large sandy str ...

and on dipping it into the well placed it back upon his neck and was restored to full health.Charles-Edwards, ''Early Christian Ireland'', p. 467 n. 82.

Classical antiquity

The ancient Greeks and Romans regarded decapitation as a comparatively honorable form of execution for criminals. The traditional procedure, however, included first being tied to a stake and whipped with rods. Axes were used by the Romans, and later swords, which were considered a more honorable instrument of death. Those who could verify that they were Roman citizens were to be beheaded, rather than undergoing

The ancient Greeks and Romans regarded decapitation as a comparatively honorable form of execution for criminals. The traditional procedure, however, included first being tied to a stake and whipped with rods. Axes were used by the Romans, and later swords, which were considered a more honorable instrument of death. Those who could verify that they were Roman citizens were to be beheaded, rather than undergoing crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the condemned is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross, beam or stake and left to hang until eventual death. It was used as a punishment by the Achaemenid Empire, Persians, Ancient Carthag ...

. In the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

of the early 1st century BC, it became the tradition for the severed heads of public enemies—such as the political opponents of Marius and Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (, ; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman of the late Roman Republic. A great commander and ruthless politician, Sulla used violence to advance his career and his co ...

—to be publicly displayed on the Rostra

The Rostra () was a large platform built in the city of Rome that stood during the republican and imperial periods. Speakers would stand on the rostra and face the north side of the Comitium towards the senate house and deliver orations to t ...

in the Forum Romanum

A forum (Latin: ''forum'', "public place outdoors", : ''fora''; English : either ''fora'' or ''forums'') was a public square in a municipium, or any civitas, of Ancient Rome reserved primarily for the vending of goods; i.e., a marketplace, along ...

after execution. Perhaps the most famous beheading was that of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

who, on instructions from Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman people, Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the Crisis of the Roman Republic, transformation of the Roman Republic ...

, had his hands (which had penned the ''Philippicae

The ''Philippics'' () are a series of 14 speeches composed by Cicero in 44 and 43 BC, condemning Mark Antony. Cicero likened these speeches to those of Demosthenes against Philip II of Macedon; both Demosthenes' and Cicero's speeches became ...

'' against Antony) and his head cut off and nailed up for display in this manner.

France

In France, until the abolition of capital punishment in 1981, the main method of execution had been by beheading by means of theguillotine

A guillotine ( ) is an apparatus designed for effectively carrying out executions by Decapitation, beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secur ...

. Other than a small number of military cases in which a firing squad was used (including that of Jean Bastien-Thiry), the guillotine was the only legal method of execution from 1791, when it was introduced by the Legislative Assembly during the last days of the kingdom French Revolution, until 1981. Before the revolution, beheading had typically been reserved for noblemen and carried out manually. In 1981, President François Mitterrand

François Maurice Adrien Marie Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was a French politician and statesman who served as President of France from 1981 to 1995, the longest holder of that position in the history of France. As a former First ...

abolished capital punishment and issued commutations for those whose sentences had not been carried out.

The first person executed by the guillotine in France was highwayman Nicolas Jacques Pelletier in April 1792. The last execution was of murderer Hamida Djandoubi

Hamida Djandoubi (; 22 September 1949 – 10 September 1977) was a Tunisian convicted murderer sentenced to death in France. He moved to Marseille in 1968, and six years later he was convicted of the kidnapping, torture and murder of 21-year-old ...

, in Marseille, in 1977. Throughout its extensive overseas colonies and dependencies, the device was also used, including on St Pierre in 1889 and on Martinique

Martinique ( ; or ; Kalinago language, Kalinago: or ) is an island in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the eastern Caribbean Sea. It was previously known as Iguanacaera which translates to iguana island in Carib language, Kariʼn ...

as late as 1965.

Germany

*Fritz Haarmann

Friedrich Heinrich Karl "Fritz" Haarmann (25 October 1879 – 15 April 1925) was a German serial rapist and serial killer, known as the Butcher of Hanover, the Vampire of Hanover and the Wolf Man, who committed the sexual assault, murder, mutil ...

, a serial killer from Hannover

Hanover ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the States of Germany, German state of Lower Saxony. Its population of 535,932 (2021) makes it the List of cities in Germany by population, 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-l ...

who was sentenced to death for killing 27 young men, was decapitated in April 1925. He was nicknamed "The Butcher from Hannover" and was rumored to have sold his victims' flesh to his neighbor's restaurant.

* In July 1931, notorious serial killer Peter Kürten, known as "The Vampire of Düsseldorf", was executed on the guillotine in Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

.

* On 1 August 1933, in Altona, Bruno Tesch and three others were beheaded. These were the first executions in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

. The executions concerned the Altona Bloody Sunday

Altona Bloody Sunday () is the name given to the events of 17 July 1932 when a recruitment march by the Sturmabteilung, Nazi SA led to violent clashes between the police, the SA and supporters of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) in Alt ...

(''Altonaer Blutsonntag'') riot, an SA march on 17 July 1932 that turned violent and led to 18 people being shot dead.

* Marinus van der Lubbe

Marinus van der Lubbe (; 13 January 1909 – 10 January 1934) was a Dutch communist who was tried, convicted, and executed by the government of Nazi Germany for setting fire to the Reichstag building—the national parliament of Germany—on ...

by guillotine in 1934 after a show trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the guilt (law), guilt or innocence of the defendant has already been determined. The purpose of holding a show trial is to present both accusation and verdict to the public, serving as an example and a d ...

in which he was found guilty of starting the Reichstag fire

The Reichstag fire (, ) was an arson attack on the Reichstag building, home of the German parliament in Berlin, on Monday, 27 February 1933, precisely four weeks after Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of Germany. Marinus van der Lubbe, ...

.

* In February 1935 Benita von Falkenhayn and Renate von Natzmer were beheaded with the axe and block in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

for espionage for Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

. Axe beheading was the only method of execution in Berlin until 1938, when it was decreed that all civil executions would henceforth be carried out by guillotine. However, the practice was continued in rare cases such as that of Olga Bancic and Werner Seelenbinder in 1944. Beheading by guillotine survived in West Germany until 1949 and in East Germany until 1966.

* A group of three Catholic clergymen, Johannes Prassek, Eduard Müller and Hermann Lange, and an Evangelical Lutheran pastor, Karl Friedrich Stellbrink, were arrested following the bombing of Lübeck, tried by the People's Court in 1943 and sentenced to death by decapitation; all were beheaded on 10 November 1943, in the Hamburg prison at Holstenglacis. Stellbrink had explained the raid next morning in his Palm Sunday sermon as a "trial by ordeal", which the Nazi authorities interpreted to be an attack on their system of government and as such undermined morale and aided the enemy.

* In October 1944, Werner Seelenbinder was executed by manual beheading, the last legal use of the method (other than by guillotine) in both Europe and the rest of the Western world. Earlier the same year, Olga Bancic had been executed by the same means.

* In February 1943, American academic Mildred Harnack and the university students Hans Scholl, Sophie Scholl

Sophia Magdalena Scholl (9 May 1921 – 22 February 1943) was a German student and anti-Nazi political activist, active in the White Rose non-violent German resistance to Nazism, resistance group in Nazi Germany.

Raised in a politically engag ...

, and Christoph Probst of the White Rose

The White Rose (, ) was a Nonviolence, non-violent, intellectual German resistance to Nazism, resistance group in Nazi Germany which was led by five students and one professor at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, University of Munich ...

protest movement, were all beheaded by the Nazi State. Four other members of the White Rose

The White Rose (, ) was a Nonviolence, non-violent, intellectual German resistance to Nazism, resistance group in Nazi Germany which was led by five students and one professor at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, University of Munich ...

, an anti-Nazi group, were also executed by the People's Court later that same year. The anti-Nazi Helmuth Hübener was also decapitated by People's Court order.

* In 1966, former Auschwitz

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It consisted of Auschw ...

doctor Horst Fischer was executed by the German Democratic Republic

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

by guillotine, the last executed by this method in Europe outside France. Beheading was subsequently replaced by shooting in the neck.

Nordic countries

InNordic countries

The Nordic countries (also known as the Nordics or ''Norden''; ) are a geographical and cultural region in Northern Europe, as well as the Arctic Ocean, Arctic and Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic oceans. It includes the sovereign states of Denm ...

, decapitation was the usual means of carrying out capital punishment. Noblemen were beheaded with a sword

A sword is an edged and bladed weapons, edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter ...

, and commoners with an axe

An axe (; sometimes spelled ax in American English; American and British English spelling differences#Miscellaneous spelling differences, see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for thousands of years to shape, split, a ...

. The last executions by decapitation in Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

in 1825, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

in 1876, Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

in 1609, and in Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

in 1830 were carried out with axes. The same was the case in Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

in 1892. Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

continued the practice for a few decades, executing its second to last criminal—mass murderer Johan Filip Nordlund—by axe in 1900. It was replaced by the guillotine, which was used for the first and only time on Johan Alfred Ander in 1910.

Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

's official beheading axe resides today at the Museum of Crime in Vantaa

Vantaa (; , ) is a city in Finland. It is located to the north of the capital, Helsinki, in southern Uusimaa. The population of Vantaa is approximately . It is the most populous municipality in Finland. Vantaa is part of the Helsinki Metropoli ...

. It is a broad-bladed two-handed axe. It was last used when murderer Tahvo Putkonen was executed in 1825, the last execution in peacetime in Finland.

Spain

In Spain executions were carried out by various methods including strangulation by the garrotte. In the 16th and 17th centuries, noblemen were sometimes executed by means of beheading. Examples includeAnthony van Stralen, Lord of Merksem

Anthony van Stralen (1521 - executed, Vilvoorde, 24 September 1568), Lord of Merksem, Lord of Dambrugghe was a Mayor of Antwerp. Although he was Roman Catholic, he became a famous victim of the terror of the Duke of Alva.

Family

He was the s ...

, Lamoral, Count of Egmont

Lamoral, Count of Egmont, Prince of Gavere (18 November 1522 – 5 June 1568) was a general and statesman in the Habsburg Netherlands, Spanish Netherlands just before the start of the Eighty Years' War, whose execution helped spark the national up ...

and Philip de Montmorency, Count of Horn

Philip de Montmorency (ca. 1524 – 5 June 1568 in Brussels), also known as Count of County of Horn, Horn, ''Horne'', ''Hoorne'' or ''Hoorn'', was a victim of the Inquisition in the Spanish Netherlands.

Biography

De Montmorency was born as the e ...

. They were tied to a chair on a scaffold. The executioner used a knife to cut the head from the body. It was considered to be a more honourable death if the executioner started with cutting the throat.

Middle East

Iran

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, since the 1979 Islamic Revolution

The Iranian Revolution (, ), also known as the 1979 Revolution, or the Islamic Revolution of 1979 (, ) was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1979. The revolution led to the replacement of the Im ...

, has alleged it uses beheading as one of the methods of punishment.

Iraq

Though not officially sanctioned, legal beheadings were carried out against at least 50 prostitutes and pimps underSaddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein (28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician and revolutionary who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 1979 until Saddam Hussein statue destruction, his overthrow in 2003 during the 2003 invasion of Ira ...

as late as 2000.

Beheadings have emerged as another terror tactic especially in Iraq since 2003. Civilians have borne the brunt of the beheadings, although U.S. and Iraqi military personnel have also been targeted. After kidnapping the victim, the kidnappers typically make some sort of demand of the government of the hostage's nation and give a time limit for the demand to be carried out, often 72 hours. Beheading is often threatened if the government fails to heed the wishes of the hostage takers. Sometimes, the beheadings are videotaped and made available on the Internet. One of the most publicized of such executions was that of Nick Berg.

Judicial execution is practiced in Iraq, but is generally carried out by hanging

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia has a criminal justice system based onShari'ah

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' refers to immutable, intan ...

law reflecting a particular state-sanctioned interpretation of Islam. Crimes such as rape, murder, apostasy, and sorcery are punishable by beheading. It is usually carried out publicly by beheading with a sword.

A public beheading will typically take place around 9am. The convicted person is walked into the square and kneels in front of the executioner. The executioner uses a sword to remove the condemned person's head from his or her body at the neck with a single strike. After the convicted person is pronounced dead, a police official announces the crimes committed by the beheaded alleged criminal and the process is complete. The official might announce the same before the actual execution. This is the most common method of execution in Saudi Arabia.

According to Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says that it has more than ten million members a ...

, at least 79 people were executed in Saudi Arabia in 2013. Foreigners are not exempt, accounting for "almost half" of executions in 2013.

In 2015 Ashraf Fayadh (born 1980), a Saudi Arabian poet, was sentenced to be beheaded, but his sentence was later reduced to eight years in prison and 800 lashes, for apostasy

Apostasy (; ) is the formal religious disaffiliation, disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that is contrary to one's previous re ...

.

Syria

The Syrian government employs hanging as its method of capital punishment. However, the terrorist organisation known as theIslamic State

The Islamic State (IS), also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Daesh, is a transnational Salafi jihadism, Salafi jihadist organization and unrecognized quasi-state. IS ...

, which controlled territory in much of eastern Syria, had regularly carried out beheadings of people. Syrian rebels attempting to overthrow the Syrian government have been implicated in beheadings too.

North America

Mexico

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla

Don Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla Gallaga Mandarte y Villaseñor (8 May 1753 – 30 July 1811), commonly known as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla or simply Miguel Hidalgo (), was a Catholic priest, leader of the Mexican War ...

, Ignacio Allende

Ignacio José de Allende y Unzaga (, , ; January 21, 1769 – June 26, 1811), commonly known as Ignacio Allende, was a captain of the Spanish Army in New Spain who came to sympathize with the Mexican independence movement. He attended the secre ...

, José Mariano Jiménez and Juan Aldama

Juan Aldama (January 3, 1774 in San Miguel el Grande, Guanajuato – June 26, 1811 in Chihuahua) was a Mexican revolutionary rebel soldier during the Mexican War of Independence in 1810.

Biography

He was also the brother of Ignacio Ald ...

were tried for treason, executed by firing squad

Firing may refer to:

* Dismissal (employment), sudden loss of employment by termination

* Firemaking, the act of starting a fire

* Burning; see combustion

* Shooting, specifically the discharge of firearms

* Execution by firing squad, a method of ...

and beheaded during the Mexican independence in 1811. Their heads were on display on the four corners of the Alhóndiga de Granaditas

Alhóndiga is a municipality located in the province of Guadalajara, Castilla–La Mancha, Spain. As of 1 January 2022 it had a registered population of 158. The municipality spans across a total area of 19.26 km2.

The locality was an early in ...

, in Guanajuato

Guanajuato, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato, is one of the 32 states that make up the Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into Municipalities of Guanajuato, 46 municipalities and its cap ...

.

During the Mexican Drug War

The Mexican drug war is an List of ongoing armed conflicts, ongoing Asymmetric warfare, asymmetric armed conflict between the Federal government of Mexico, Mexican government and various Drug cartel#Mexico, drug trafficking syndicates. When the ...

, some Mexican drug cartels turned to decapitation and beheading of rival cartel members as a method of intimidation.

This trend of beheading and publicly displaying the decapitated bodies was started by the Los Zetas

Los Zetas (, Spanish for "The Zs") is a Mexican criminal syndicate and designated terrorist organization, known as one of the most dangerous of Mexico's drug cartels. They are known for engaging in brutally violent " shock and awe" tactics suc ...

, a criminal group composed by former Mexican special forces operators, trained in the infamous ''US Army School of the Americas

The Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC), formerly the School of the Americas, is a United States Department of Defense school located at Fort Benning (briefly known as Fort Moore) in Columbus, Georgia, the school bein ...

'', in torture techniques and psychological warfare

Psychological warfare (PSYWAR), or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations (PsyOp), has been known by many other names or terms, including Military Information Support Operations ( MISO), Psy Ops, political warfare, "Hearts and Mi ...

.

United States

The United States government has never employed beheading as a legal method of execution. However, beheading has sometimes been used in mutilations of the dead, particularly of black people likeNat Turner

Nat Turner (October 2, 1800 – November 11, 1831) was an enslaved Black carpenter and preacher who led a four-day rebellion of both enslaved and free Black people in Southampton County, Virginia in August 1831.

Nat Turner's Rebellion res ...

, who led a rebellion against slavery. When caught, he was publicly hanged, flayed, and beheaded. This was a technique used by many enslavers to discourage the "frequent bloody uprisings" that were carried out by "kidnapped Africans". While bodily dismemberment of various kinds was employed to instill terror, Dr. Erasmus D. Fenner noted postmortem decapitation was particularly effective.

During the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, as a terror tactic, "some American troops hacked the heads off... dead ietnameseand mounted them on pikes or poles". Correspondent Michael Herr noted "thousands" of photo-albums made by US soldiers "all seemed to contain the same pictures": "the severed head shot, the head often resting on the chest of the dead man or being held up by a smiling Marine, or a lot of the heads, arranged in a row, with a burning cigarette in each of the mouths, the eyes open". Some of the victims were "very young".

General George Patton IV, son of the famous WWII general George S. Patton, was known for keeping "macabre souvenirs", such as "a Vietnamese skull that sat on his desk." Other Americans "hacked the heads off Vietnamese to keep, trade, or exchange for prizes offered by commanders."

Although the Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th st ...

permitted a person sentenced to death to choose beheading as a means of execution, no person chose that option, and it was dropped when Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

became a state.

Notable people who have been beheaded

See also

* Atlanto-occipital dislocation, where theskull

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

is dislodged from the spine

Spine or spinal may refer to:

Science Biology

* Spinal column, also known as the backbone

* Dendritic spine, a small membranous protrusion from a neuron's dendrite

* Thorns, spines, and prickles, needle-like structures in plants

* Spine (zoology), ...

; a generally, but not always, fatal injury.

* Beheading in Islam

* Beheading video

* Blood atonement

* Blood squirt, a result from a decapitation.

* Cephalophore

A cephalophore (from the Greek for 'head-carrier') is a saint who is generally depicted carrying their severed head. In Christian art, this was usually meant to signify that the subject in question had been martyred by beheading. Depicting the ...

, a martyred saint who is depicted carrying their severed head.

* Chhinnamasta

Chhinnamasta (, :"She whose head is severed"), often spelled Chinnamasta, and also called Chhinnamastika, Chhinnamasta Kali, Prachanda Chandika and Jogani Maa (in western states of India), is a Hindu goddess ( Devi). She is one of the Maha ...

, a Hindu goddess who supposedly decapitates herself and holds her head in her hand.

* Cleveland Torso Murderer, a serial killer

A serial killer (also called a serial murderer) is a person who murders three or more people,An offender can be anyone:

*

*

*

*

* (This source only requires two people) with the killings taking place over a significant period of time in separat ...

who decapitated some of his victims.

* Dismemberment