debt trap on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Usury () is the practice of making

The Talmud on usury

Economic Affairs, 43(3), 423–435.

What Love Is This? A Renunciation of the Economics of Calvinism

The House of Degenhart.

S.C. Mooney's Response to Dr. Gary North's critique of Usury: Destroyer of NationsUsury laws by state.

Heretical.com

Thomas Geoghegan on "Infinite Debt: How Unlimited Interest Rates Destroyed the Economy"

{{Debt Usury, Medieval economic history Economic bubbles Property crimes Negative Mitzvoth

loan

In finance, a loan is the tender of money by one party to another with an agreement to pay it back. The recipient, or borrower, incurs a debt and is usually required to pay interest for the use of the money.

The document evidencing the deb ...

s that are seen as unfairly enriching the lender

A creditor or lender is a party (e.g., person, organization, company, or government) that has a claim on the services of a second party. It is a person or institution to whom money is owed. The first party, in general, has provided some property ...

. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, ...

is charged in excess of the maximum rate that is allowed by law. A loan may be considered usurious because of excessive or abusive interest rates or other factors defined by the laws of a state. Someone who practices usury can be called a ''usurer'', but in modern colloquial English may be called a ''loan shark

A loan shark is a person who offers loans at Usury, extremely high or illegal interest rates, has strict terms of debt collection, collection, and generally operates criminal, outside the law, often using the threat of violence or other illegal, ...

''.

In many historical societies including ancient Christian, Jewish, and Islamic societies, usury meant the charging of interest

In finance and economics, interest is payment from a debtor or deposit-taking financial institution to a lender or depositor of an amount above repayment of the principal sum (that is, the amount borrowed), at a particular rate. It is distinct f ...

of any kind, and was considered wrong, or was made illegal. During the Sutra period in India (7th to 2nd centuries BC) there were laws prohibiting the highest castes from practicing usury. Similar condemnations are found in religious texts from Buddhism, Judaism (''ribbit

Ribbit may refer to:

* Onomatopoeia for the sound that a frog makes.

* Ribbit (Pillow Pal), a plush toy frog made by Ty, Inc.

* Ribbit (telecommunications company), a telecommunications company based in Mountain View, California, acquired by BT ...

'' in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

), Christianity, and Islam (''riba

''Riba'' (, or , ) is an Arabic word used in Islamic law and roughly translated as " usury": unjust, exploitative gains made in trade or business. ''Riba'' is mentioned and condemned in several different verses in the Qur'an3:130

'' in Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

). At times, many states from ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

to ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

have outlawed loans with any interest. Though the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

eventually allowed loans with carefully restricted interest rates, the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

in medieval Europe, as well as the Reformed Churches, regarded the charging of interest at any rate as sin

In religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law or a law of the deities. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered ...

ful (as well as charging a fee for the use of money, such as at a bureau de change

A bureau de change (plural bureaux de change, both ; British English) or currency exchange (Comparison of American and British English, American English) is a business where people can exchange one currency for another.

Nomenclature

Original ...

). Christian religious prohibitions on usury are predicated upon the belief that charging interest on a loan is a sin.

History

Usury (in the original sense of any interest) was denounced by religious leaders and philosophers in the ancient world, includingMoses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

, Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, Cato, Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

, Seneca, Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

, Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha (),*

*

*

was a śramaṇa, wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism. According to Buddhist lege ...

and Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

.

Certain negative historical renditions of usury carry with them social connotations of perceived "unjust" or "discriminatory" lending practices. The historian Paul Johnson comments:

Theological historian John Noonan argues that "the doctrine f usurywas enunciated by popes, expressed by three ecumenical councils, proclaimed by bishops, and taught unanimously by theologians."

England

In England, the departingCrusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding ...

were joined by crowds of debtors in the massacres of Jews at London and York in 1189–1190. In 1275, Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 1254 ...

passed the Statute of the Jewry which made usury illegal and linked it to blasphemy

Blasphemy refers to an insult that shows contempt, disrespect or lack of Reverence (emotion), reverence concerning a deity, an object considered sacred, or something considered Sanctity of life, inviolable. Some religions, especially Abrahamic o ...

, in order to seize the assets of the violators. Scores of English Jews were arrested, 300 were hanged and their property went to the Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

. In 1290, all Jews were to be expelled from England, allowed to take only what they could carry; the rest of their property became the Crown's. Usury was cited as the official reason for the Edict of Expulsion

The Edict of Expulsion was a royal decree expelling all Jews from the Kingdom of England that was issued by Edward I of England, Edward I on 18 July 1290; it was the first time a European state is known to have permanently banned their prese ...

; however, not all Jews were expelled: it was easy to avoid expulsion by converting to Christianity. Many other crowned heads of Europe expelled Jewish people, although again converts to Christianity were no longer considered Jewish. Many of these forced converts still secretly practiced their faith.

The growth of the Lombard bankers and pawnbroker

A pawnbroker is an individual that offers secured loans to people, with items of personal property used as Collateral (finance), collateral. A pawnbrokering business is called a pawnshop, and while many items can be pawned, pawnshops typic ...

s, who moved from city to city, was along the pilgrim

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often vocalize it as ...

routes.

In the 16th century, short-term interest rates dropped dramatically (from around 20–30% p.a. to around 9–10% p.a.). This was caused by refined commercial techniques, increased capital availability, the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

, and other reasons. The lower rates weakened religious scruples about lending at interest, although the debate did not cease altogether.

The 18th century papal prohibition on usury meant that it was a sin to charge interest on a money loan. As set forth by Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

in the 13th century, because money was invented to be an intermediary in exchange for goods, it is unjust to charge a fee to someone after giving them money. This is because transferring ownership of property implies the right to use that property for its purpose: "Accordingly if a man wanted to sell wine separately from the use of the wine, he would be selling the same thing twice, or he would be selling what does not exist, wherefore he would evidently commit a sin of injustice."

Charles Eisenstein has argued that pivotal change in the English-speaking world came with lawful rights to charge interest on lent money, particularly the 1545 act, "An Act Against Usurie" ( 37 Hen. 8. c. 9) of King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

of England.

Roman Empire

During thePrincipate

The Principate was the form of imperial government of the Roman Empire from the beginning of the reign of Augustus in 27 BC to the end of the Crisis of the Third Century in AD 284, after which it evolved into the Dominate. The principate was ch ...

period, most banking activities were conducted by private individuals who operated as large banking firms do today. Anybody that had any available liquid assets and wished to lend it out could easily do so.

The annual rates of interest on loans varied in the range of 4–12 percent, but when the interest rate was higher, it typically was not 15–16 percent but either 24 percent or 48 percent. They quoted them on a monthly basis, and the most common rates were multiples of twelve. Monthly rates tended to range from simple fractions to 3–4 percent, perhaps because lenders used Roman numerals

Roman numerals are a numeral system that originated in ancient Rome and remained the usual way of writing numbers throughout Europe well into the Late Middle Ages. Numbers are written with combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet, eac ...

.

During this period, moneylending primarily involved private loans given to individuals who were consistently in debt or temporarily so until harvest time. This practice was typically carried out by extremely wealthy individuals willing to take on high risks if the potential profit seemed promising. Interest rates were set privately and were largely unrestricted by law. Investment was always regarded as a matter of seeking personal profit, often on a large scale. Banking was of the small, back-street variety, run by the urban lower-middle class of petty shopkeepers. By the 3rd century, acute currency problems in the Empire drove such banking into decline. The rich who were in a position to take advantage of the situation became the moneylenders when the increasing tax demands in the last declining days of the Empire crippled and eventually destroyed the peasant class by reducing tenant-farmers to serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed dur ...

. It was evident that usury meant exploitation of the poor.

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

, in the second book of his treatise ''De Officiis

''De Officiis'' (''On Duties'', ''On Obligations'', or ''On Moral Responsibilities'') is a 44 BC treatise by Marcus Tullius Cicero divided into three books, in which Cicero expounds his conception of the best way to live, behave, and observe mor ...

'', relates the following conversation between an unnamed questioner and Cato:

Religion

Judaism

The book ofDeuteronomy

Deuteronomy (; ) is the fifth book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called () which makes it the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible and Christian Old Testament.

Chapters 1–30 of the book consist of three sermons or speeches delivered to ...

prohibits Jews from charging interest except when making loans to foreigners. Typically, a loan is considered a form of ''Tzedakah'' or ''Ṣedaqah'' ( s(e)daˈka, a Hebrew word meaning "righteousness" but commonly used to signify ''charity

Charity may refer to:

Common meanings

* Charitable organization or charity, a non-profit organization whose primary objectives are philanthropy and social well-being of persons

* Charity (practice), the practice of being benevolent, giving and sha ...

''. (This concept of "charity" differs from the modern Western understanding of "charity". The latter is typically understood as a spontaneous act of goodwill and a marker of generosity; ''tzedakah'' is an ethical obligation.) In the Rabbinic period, the practice of charging interest to non-Jews has been restricted to cases when there is no other means of subsistence. "If we nowadays allow interest to be taken from non-Jews, it is because there is no end to the yoke and the burden king and ministers impose on us, and everything we take is the minimum for our subsistence, and anyhow we are condemned to live in the midst of the nations

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, territory, or societ ...

and cannot earn our living in any other manner except by money dealings with them; therefore the taking of interest is not to be prohibited" (Tos. to BM 70b S.V. tashikh).

This is outlined in the Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They often feature a compilation or discussion of beliefs, ritual practices, moral commandments and ...

s, specifically in the Torah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

:

Johnson contends that the Torah treats lending as philanthropy

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the Public good (economics), public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private goo ...

in a poor community whose aim was collective survival, but which is not obliged to be charitable towards outsiders.

As Jewish people were ostracized from most professions by local rulers during the Middle Ages, the Western churches and the guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

s, they were pushed into marginal occupations considered socially inferior, such as tax

A tax is a mandatory financial charge or levy imposed on an individual or legal entity by a governmental organization to support government spending and public expenditures collectively or to regulate and reduce negative externalities. Tax co ...

and rent collecting and moneylending. Natural tensions between creditors and debtors were added to social, political, religious, and economic strains.

Several historical rulings in Jewish law

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is based on biblical commandments ('' mit ...

have mitigated the allowances for usury toward non-Jews. For instance, the 15th-century commentator Rabbi Isaac Abarbanel specified that the rubric for allowing interest does not apply to Christians or Muslims, because their faith systems have a common ethical basis originating from Judaism. The medieval commentator Rabbi David Kimhi extended this principle to non-Jews who show consideration for Jews, saying they should be treated with the same consideration when they borrow.

Christianity

Bible

TheOld Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

"condemns the practice of charging interest on a poor person because a loan should be an act of compassion and taking care of one’s neighbor"; it teaches that "making a profit off a loan from a poor person is exploiting that person (Exodus 22:25–27)." Similarly, charging of interest () or the taking of clothing as pledges is condemned in Ezekiel 18 (early 6th century BC), and Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy (; ) is the fifth book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called () which makes it the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible and Christian Old Testament.

Chapters 1–30 of the book consist of three sermons or speeches delivered to ...

23:19 prohibits the taking of interest in the form of money or food when lending to a "brother".

The New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

likewise teaches giving rather than loaning money to those who need it:

"And if you lend to those from whom you expect repayment, what credit is that to you? Even sinners lend to sinners, expecting to be repaid in full. But love your enemies, do good to them, and lend to them, expecting nothing in return. Then your reward will be great, and you will be sons of the Most High; for He is kind to the ungrateful and wicked. Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful. - Luke 6:34-36 NIV

Church councils

TheFirst Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea ( ; ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I. The Council of Nicaea met from May until the end of July 325.

This ec ...

, in 325, forbade clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

from engaging in usury

At the time, usury was interest

In finance and economics, interest is payment from a debtor or deposit-taking financial institution to a lender or depositor of an amount above repayment of the principal sum (that is, the amount borrowed), at a particular rate. It is distinct f ...

of any kind, and the canon forbade the clergy to lend money at interest rates even as low as 1 percent per year. Later ecumenical council

An ecumenical council, also called general council, is a meeting of bishops and other church authorities to consider and rule on questions of Christian doctrine, administration, discipline, and other matters in which those entitled to vote are ...

s applied this regulation to the laity

In religious organizations, the laity () — individually a layperson, layman or laywoman — consists of all Church membership, members who are not part of the clergy, usually including any non-Ordination, ordained members of religious orders, e ...

.Noonan, John T., Jr. 1993. "Development of Moral Doctrine." 54 Theological Stud. 662.

Lateran III decreed that persons who accepted interest on loans could receive neither the sacrament

A sacrament is a Christian rite which is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence, number and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol ...

s nor Christian burial.

The Council of Vienne made the belief in the right to usury a heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

in 1311, and condemned all secular legislation that allowed it.

Up to the 16th century, usury was condemned by the Catholic Church. During the Fifth Lateran Council, in the 10th session (in the year 1515), the Council for the first time gave a definition of usury:

The Fifth Lateran Council, in the same declaration, gave explicit approval of charging a fee for services ''so long as no profit was made'' in the case of Mounts of Piety

Mount is often used as part of the name of specific mountains, e.g. Mount Everest.

Mount or Mounts may also refer to:

Places

* Mount, Cornwall, a village in Warleggan parish, England

* Mount, Perranzabuloe, a hamlet in Perranzabuloe parish, ...

:

Pope Sixtus V

Pope Sixtus V (; 13 December 1521 – 27 August 1590), born Felice Piergentile, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 April 1585 to his death, in August 1590. As a youth, he joined the Franciscan order, where h ...

condemned the practice of charging interest as "detestable to God and man, damned by the sacred canons, and contrary to Christian charity.

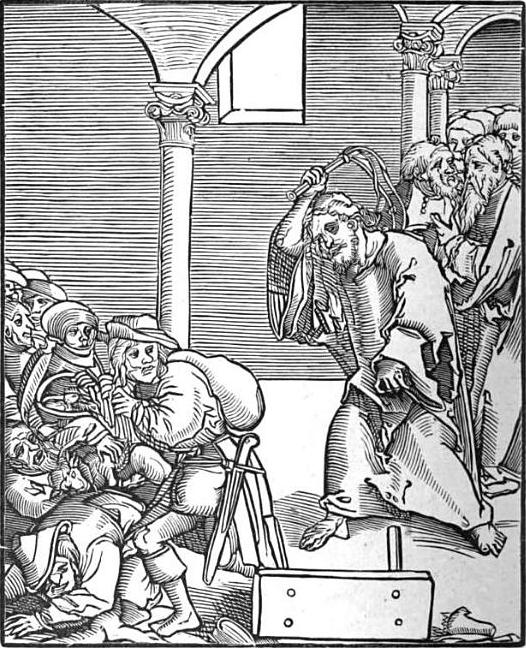

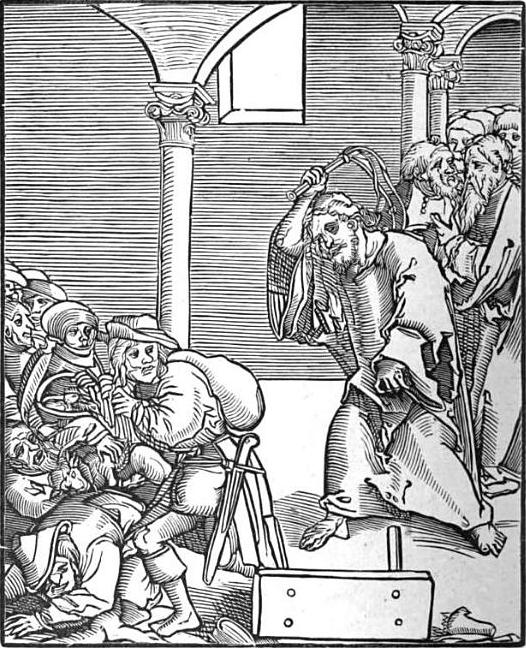

Medieval theology

The first of the scholastic Christian theologians, Saint Anselm of Canterbury, led the shift in thought that labelled charging interest the same as theft. Previously usury had been seen as a lack ofcharity

Charity may refer to:

Common meanings

* Charitable organization or charity, a non-profit organization whose primary objectives are philanthropy and social well-being of persons

* Charity (practice), the practice of being benevolent, giving and sha ...

.

St. Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

, the leading scholastic theologian of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, argued charging of interest is wrong because it amounts to "double charging", charging for both the thing and the use of the thing. Aquinas said this would be morally wrong in the same way as if one sold a bottle of wine, charged for the bottle of wine, and then charged for the person using the wine to actually drink it. Similarly, one cannot charge for a piece of cake and for the eating of the piece of cake. Yet this, said Aquinas, is what usury does. Money is a medium of exchange, and is used up when it is spent. To charge for the money and for its use (by spending) is therefore to charge for the money twice. It is also to sell time since the usurer charges, in effect, for the time that the money is in the hands of the borrower. Time, however, is not a commodity for which anyone can charge. In condemning usury Aquinas was much influenced by the recently rediscovered philosophical writings of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

and his desire to assimilate Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysic ...

with Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology – the systematic study of the divine and religion – of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. It concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Ch ...

. Aquinas argued that in the case of usury, as in other aspects of Christian revelation, Christian doctrine is reinforced by Aristotelian natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

rationalism. Aristotle's argument is that interest is unnatural, since money, as a sterile element, cannot naturally reproduce itself. Thus, usury conflicts with natural law just as it offends Christian revelation: see Thought of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest, the foremost Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the Western tradition. A Doctor of the Church, he wa ...

. As such, Aquinas taught "that interest is inherently unjust and one who charges interest sins."

Outlawing usury did not prevent investment, but stipulated that in order for the investor to share in the profit he must share the risk. In short he must be a joint-venturer. Simply to invest the money and expect it to be returned regardless of the success of the venture was to make money simply by having money and not by taking any risk or by doing any work or by any effort or sacrifice at all, which is usury. St Thomas quotes Aristotle as saying that "to live by usury is exceedingly unnatural". St Thomas allows, however, charges for actual services provided. Thus a banker or credit-lender could charge for such actual work or effort as he did carry out e.g. any fair administrative charges. The Catholic Church, in a decree of the Fifth Council of the Lateran, expressly allowed such charges in respect of credit-unions run for the benefit of the poor known as " montes pietatis".

In the 13th century Cardinal Hostiensis enumerated thirteen situations in which charging interest was not immoral. The most important of these was ''lucrum cessans'' (profits given up) which allowed for the lender to charge interest "to compensate him for profit foregone in investing the money himself." This idea is very similar to opportunity cost. Many scholastic thinkers who argued for a ban on interest charges also argued for the legitimacy of ''lucrum cessans'' profits (e.g. Pierre Jean Olivi and St. Bernardino of Siena). However, Hostiensis' exceptions, including for ''lucrum cessans'', were never accepted as official by the Catholic Church.

Pope Benedict XIV

Pope Benedict XIV (; ; 31 March 1675 – 3 May 1758), born Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 17 August 1740 to his death in May 1758. Pope Benedict X (1058–1059) is now con ...

's encyclical '' Vix Pervenit'' (1745), operating in the pre-industrial mindset , gives the reasons why usury is sinful:

The nature of the sin called usury has its proper place and origin in a loan contract...hich Ij () is a village in Golabar Rural District of the Central District in Ijrud County, Zanjan province, Iran Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq ...demands, by its very nature, that one return to another only as much as he has received. The sin rests on the fact that sometimes the creditor desires more than he has given..., but any gain which exceeds the amount he gave is illicit and usurious.

One cannot condone the sin of usury by arguing that the gain is not great or excessive, but rather moderate or small; neither can it be condoned by arguing that the borrower is rich; nor even by arguing that the money borrowed is not left idle, but is spent usefully...

15th through 19th century

Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

opposed several forms of usury, publishing and republishing multiple treatises on the subject. Christians, Luther argued, should not act in self-defense, should give when asked, and in the lowest degree should lend, expecting nothing in return. On those grounds, making a loan with anticipated profits (and with required repayment and hence little risk for the lender) is a form of self-service that goes against love of neighbor. Defining "lend" as lending without interest or fee, Luther encourages lending for the purpose of aiding the borrower.

The Westminster Larger Catechism

The Westminster Larger Catechism, along with the Westminster Shorter Catechism, is a central catechism of Calvinists in the English tradition throughout the world.

History

In 1643 when the Long Parliament of England called the Westminster ...

, part of the Westminster Standards held as doctrinal documents by Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

churches, teaches that usury is a sin

In religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law or a law of the deities. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered ...

prohibited by the eighth commandment.

Concerns about usury included the 19th century Rothschild loans to the Holy See and 16th century concerns over abuse of the zinskauf clause. This was problematic because the charging of interest (although not all interest – see above for Fifth Lateran Council) can be argued to be a violation of doctrine at the time, such as that reflected in the 1745 encyclical ''Vix pervenit''. To prevent any claims of doctrine violation, work-arounds would sometimes be employed. For example, in the 15th century, the Medici Bank lent money to the Vatican, which was lax about repayment. Rather than charging interest, "the Medici overcharged the pope on the silks and brocades, the jewels and other commodities they supplied."

20th century

The1917 Code of Canon Law

The 1917 ''Code of Canon Law'' (abbreviated 1917 CIC, from its Latin title ), also referred to as the Pio-Benedictine Code,Dr. Edward Peters accessed June-9-2013 is the first official comprehensive codification (law), codification of Canon law ...

instructed church administrators to set aside funds to be "invested profitably". It permitted lending with interest under normal legal conditions as long as excessive interest was not charged.

The Catholic Church has always condemned usury, but in modern times, with the rise of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

, the previous assumptions about the very nature of money have been challenged, and the Church had to update its understanding of what constitutes usury to also include the new reality. Thus, the Church refers, among other things, to the fact Mosaic Law

The Law of Moses ( ), also called the Mosaic Law, is the law said to have been revealed to Moses by God. The term primarily refers to the Torah or the first five books of the Hebrew Bible.

Terminology

The Law of Moses or Torah of Moses (Hebr ...

does not ban all interest taking (proving interest-taking is not an inherently immoral act, same principle as with homicide

Homicide is an act in which a person causes the death of another person. A homicide requires only a Volition (psychology), volitional act, or an omission, that causes the death of another, and thus a homicide may result from Accident, accidenta ...

), as well as the prevalence of bonds and loans paying interest. Because of this, as the old Catholic Encyclopedia

''The'' ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'', also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedi ...

put it, "Since the possession of an object is generally useful, I may require the price of that general utility, even when the object is of no use to me."

Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

philosopher Joseph Rickaby, writing at the beginning of the 20th century, put the development of economy in relation to usury this way:

He further gave the following view of the development of Catholic practice:

Modern era

The Congregation of the Missionary Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, a Catholic Christianreligious order

A religious order is a subgroup within a larger confessional community with a distinctive high-religiosity lifestyle and clear membership. Religious orders often trace their lineage from revered teachers, venerate their Organizational founder, ...

, teaches that the charging of interest is sinful. Theology professor Kevin Considine argues that usury remains a sin if it takes advantage of the needy or where the source of the interest is sinful:

Islam

Riba

''Riba'' (, or , ) is an Arabic word used in Islamic law and roughly translated as " usury": unjust, exploitative gains made in trade or business. ''Riba'' is mentioned and condemned in several different verses in the Qur'an3:130

(usury) is forbidden in Islam. As such, specialized codes of banking have developed to cater to investors wishing to obey Qur'anic law. ''(See Islamic banking

Islamic banking, Islamic finance ( ''masrifiyya 'islamia''), or Sharia-compliant finance is banking or financing activity that complies with Sharia (Islamic law) and its practical application through the development of Islamic economics. Some ...

)''

The following quotations are English translations from the Qur'an

The Quran, also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God ('' Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which consist of individual verses ('). Besides ...

:

Those who consume interest will stand (on Judgment Day) like those driven to madness by Satan’s touch. That is because they say, "Trade is no different than interest." But Allah has permitted trading and forbidden interest. Whoever refrains—after having received warning from their Lord—may keep their previous gains, and their case is left to Allah. As for those who persist, it is they who will be the residents of the Fire. They will be there forever. (''Al-Baqarah 2:275'')

Allah has made interest fruitless and charity fruitful. And Allah does not like any ungrateful evildoer. Indeed, those who believe, do good, establish prayer, and pay alms-tax will receive their reward from their Lord, and there will be no fear for them, nor will they grieve. O believers! Fear Allah, and give up outstanding interest if you are (true) believers. If you do not, then beware of a war with Allah and His Messenger! But if you repent, you may retain your principal—neither inflicting nor suffering harm. If it is difficult for someone to repay a debt, postpone it until a time of ease. And if you waive it as an act of charity, it will be better for you, if only you knew. (''Al-Baqarah 2:276–280'')

O believers! Do not consume interest, multiplying it many times over. And be mindful of Allah, so you may prosper. (''Al-'Imran 3:130'')

We forbade the Jews certain foods that had been lawful to them for their wrongdoing, and for hindering many from the Way of Allah, taking interest despite its prohibition, and consuming people’s wealth unjustly. We have prepared for the disbelievers among them a painful punishment. (''Al-Nisa 4:160–161'')

Whatever loans you give, seeking interest at the expense of people’s wealth, will not increase with Allah. But whatever charity you give, seeking the pleasure of Allah—it is they whose reward will be multiplied. (''Ar-Rum 30:39'')The attitude of

Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

to usury is articulated in his Last Sermon:Verily your blood, your property are as sacred and inviolable as the sacredness of this day of yours, in this month of yours, in this town of yours. Behold! Everything pertaining to the Days of Ignorance is under my feet completely abolished. Abolished are also the blood-revenges of the Days of Ignorance. The first claim of ours on blood-revenge which I abolish is that of the son of Rabi'a b. al-Harith, who was nursed among the tribe of Sa'd and killed by Hudhail. And the usury of the pre-Islamic period is abolished, and the first of our usury I abolish is that of 'Abbas b. 'Abd al-Muttalib, for it is all abolished.One of the forbidden usury models in Islam is to take advantage when lending money. Examples of forbidden loans, such as a person borrowing 1000 dollars and the borrower is required to return 1100 dollars. The above agreement is a form of transaction which is a burden for people who borrow, because in Islam, lending and borrowing are social transactions aimed at helping others, not like a sale and purchase agreement that is allowed to be profitable. Hence, a rule of thumb used by Islamic scholars is, "Every loan (qardh) which gives additional benefits is called usury."

In literature

In ''The Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' (, ) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of the greatest wor ...

'', Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

places the usurers in the inner ring of the seventh circle of hell.

Interest on loans, and the contrasting views on the morality of that practice held by Jews and Christians, is central to the plot of Shakespeare's play ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan taken out on behalf of his dear friend, Bassanio, and provided by a ...

''. Antonio is the merchant of the title, a Christian, who is forced by circumstance to borrow money from Shylock, a Jew. Shylock customarily charges interest on loans, seeing it as good business, while Antonio does not, viewing it as morally wrong. When Antonio defaults on his loan, Shylock famously demands the agreed upon penalty: a measured quantity of muscle from Antonio's chest. This is the source of the metaphorical phrase "a pound of flesh" often used to describe the dear price of a loan or business transaction. Shakespeare's play is a vivid portrait of the competing views of loans and use of interest, as well as the cultural strife between Jews and Christians that overlaps it.

By the 18th century, usury was more often treated as a metaphor than a crime in itself, so Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 4 February Dual dating, 1747/8 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates, N.S.– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of mo ...

's ''Defence of Usury'' was not as shocking as it would have appeared two centuries earlier.

In Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly ; ; born Honoré Balzac; 20 May 1799 – 18 August 1850) was a French novelist and playwright. The novel sequence ''La Comédie humaine'', which presents a panorama of post-Napoleonic French life, is ...

's 1830 novel '' Gobseck'', the title character, who is a usurer, is described as both "petty and great – a miser and a philosopher..." The character Daniel Quilp in ''The Old Curiosity Shop

''The Old Curiosity Shop'' is the fourth novel by English author Charles Dickens; being one of his two novels (the other being ''Barnaby Rudge'') published along with short stories in his weekly serial ''Master Humphrey's Clock'', from 1840 t ...

'' by Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

is a usurer.

In the early 20th century Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an List of poets from the United States, American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Ita ...

's anti-usury poetry was not primarily based on the moral injustice of interest payments but on the fact that excess capital was no longer devoted to artistic patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

, as it could now be used for capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

business investment.

Usury law

England

"When money is lent on a contract to receive not only the principal sum again, but also an increase by way of compensation for the use, the increase is called ''interest'' by those who ''think'' it lawful, and ''usury'' by those who do not." (William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, Justice (title), justice, and Tory (British political party), Tory politician most noted for his ''Commentaries on the Laws of England'', which became the best-k ...

's ''Commentaries on the Laws of England

The ''Commentaries on the Laws of England'' (commonly, but informally known as ''Blackstone's Commentaries'') are an influential 18th-century treatise on the common law of England by Sir William Blackstone, originally published by the Clarend ...

'').

Canada

On the federal level, Canada's Criminal Code limits the interest rate to 60% per year. The law is broadly written and Canada's courts have often intervened to remove ambiguity. In Quebec, the maximum annual interest rate allowed by law is 35%.Hong Kong

The Money Lenders Ordinance (Cap. 163) prohibits lending at an effective interest rate beyond 48% unless exempted. Offenders are liable "on summary conviction to a fine of $500,000 and to imprisonment for 2 years", or "on conviction on indictment to a fine of $5,000,000 and to imprisonment for 10 years".Japan

Japan has various laws restricting interest rates. Under civil law, the maximum interest rate is between 15% and 20% per year depending upon the principal amount (larger amounts having a lower maximum rate). Interest in excess of 20% is subject to criminal penalties (the criminal law maximum was 29.2% until it was lowered by legislation in 2010). Default interest on late payments may be charged at up to 1.46 times the ordinary maximum (i.e., 21.9% to 29.2%), whilepawn shop

A pawnbroker is an individual that offers secured loans to people, with items of personal property used as collateral. A pawnbrokering business is called a pawnshop, and while many items can be pawned, pawnshops typically accept jewelry, ...

s may charge interest of up to 9% per month (i.e., 108% per year, however, if the loan extends more than the normal short-term pawn shop loan, the 9% per month rate compounded can make the annual rate in excess of 180%, before then most of these transaction would result in any goods pawned being forfeited).

United States

''Usury laws'' arestate law State law refers to the law of a federated state, as distinguished from the law of the federation of which it is a part. It is used when the constituent components of a federation are themselves called states. Federations made up of provinces, cant ...

s that specify the maximum legal interest rate

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, ...

at which loans can be made. In the United States, the primary legal power to regulate usury rests primarily with the states. Each U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

has its own statute

A statute is a law or formal written enactment of a legislature. Statutes typically declare, command or prohibit something. Statutes are distinguished from court law and unwritten law (also known as common law) in that they are the expressed wil ...

that dictates how much interest can be charged before it is considered usurious or unlawful.

If a lender charges above the lawful interest rate, a court will not allow the lender to sue to recover the unlawfully high interest, and some states will apply all payments made on the debt to the principal balance. In some states, such as New York, usurious loans are voided ''ab initio

( ) is a Latin term meaning "from the beginning" and is derived from the Latin ("from") + , ablative singular of ("beginning").

Etymology

, from Latin, literally "from the beginning", from ablative case of "entrance", "beginning", related t ...

''.

The making of usurious loans is often called loan shark

A loan shark is a person who offers loans at Usury, extremely high or illegal interest rates, has strict terms of debt collection, collection, and generally operates criminal, outside the law, often using the threat of violence or other illegal, ...

ing. That term is sometimes also applied to the practice of making consumer loans without a license in jurisdictions that requires lenders to be licensed.

Federal regulation

On a federal level, Congress has never attempted to federally regulate interest rates on purely private transactions, but on the basis of past U.S. Supreme Court decisions, arguably the U.S. Congress might have the power to do so under the interstatecommerce clause

The Commerce Clause describes an enumerated power listed in the United States Constitution ( Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). The clause states that the United States Congress shall have power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and amon ...

of Article I of the Constitution.

Congress imposed a federal criminal penalty for unlawful interest rates through the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act is a United States federal law that provides for extended criminal penalties and a civil cause of action for acts performed as part of an ongoing criminal organization.

RICO was e ...

(RICO Statute), and its definition of "unlawful debt", which makes it a potential federal felony to lend money at an interest rate more than twice the local state usury rate and then try to collect that debt.

It is a federal offense to use violence or threats to collect usurious interest (or any other sort).

Separate federal rules apply to most banks. The U.S. Supreme Court held unanimously in the 1978 case, '' Marquette Nat. Bank of Minneapolis v. First of Omaha Service Corp.'', that the National Banking Act of 1863 allowed nationally chartered banks to charge the legal rate of interest in their state regardless of the borrower's state of residence.''Marquette Nat. Bank of Minneapolis v. First of Omaha Service Corp.'', .

In 1980, Congress passed the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act. Among the Act's provisions, it exempted federally chartered savings banks, installment plan sellers and chartered loan companies from state usury limits. Combined with the ''Marquette'' decision that applied to National Banks, this effectively overrode all state and local usury laws. The 1968 Truth in Lending Act

The Truth in Lending Act (TILA) of 1968 is a United States federal law designed to promote the informed use of consumer credit, by requiring disclosures about its terms and cost to standardize the manner in which costs associated with borrowing ...

does not regulate rates, except for some mortgages, but requires uniform or standardized disclosure of costs and charges.

In the 1996 '' Smiley v. Citibank'' case, the Supreme Court further limited states' power to regulate credit card fees and extended the reach of the ''Marquette'' decision. The court held that the word "interest" used in the 1863 banking law included fees and, therefore, states could not regulate fees.ABA Journal, March 2010, p. 59

Some members of Congress have tried to create a federal usury statute that would limit the maximum allowable interest rate, but the measures have not progressed. In July 2010, the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act

The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, commonly referred to as Dodd–Frank, is a United States federal law that was enacted on July 21, 2010. The law overhauled financial regulation in the aftermath of the Great Reces ...

, was signed into law by President Obama. The act provides for a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is an independent agency of the United States government responsible for consumer protection in the financial sector. CFPB's jurisdiction includes banks, credit unions, securities firms, Payday lo ...

to regulate some credit practices but has no interest rate limit.

Texas

State law in Texas also includes a provision for contracting for, charging, or receiving charges exceeding twice the amount authorized (A/K/A "double usury"). A person who violates this provision is liable to the obligor as an additional penalty for all principal or principal balance, as well as interest or time price differential. A person who is liable is also liable for reasonable attorney's fees incurred by the obligor.Avoidance mechanisms and interest-free lending

Demurrage currency

Demurrage currency is a type ofmoney

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are: m ...

that is designed to gradually lose purchasing power

Purchasing power refers to the amount of products and services available for purchase with a certain currency unit. For example, if you took one unit of cash to a store in the 1950s, you could buy more products than you could now, showing that th ...

at a flat constant rate.

The German economist, Silvio Gesell, advocated for demurrage as part of the Freiwirtschaft economic system.

He referred to demurrage as '' Freigeld'' 'free money' — "free" because it would be freed from hoarding and interest.

Gesell theorized that Freigeld would lead to fewer recessions by increasing the velocity of money

image:M3 Velocity in the US.png, 300px, Similar chart showing the logged velocity (green) of a broader measure of money M3 that covers M2 plus large institutional deposits. The US no longer publishes official M3 measures, so the chart only runs t ...

, eliminating inflation, and creating an interest-free economy without usury.

Islamic banking

In a partnership or joint venture where money is lent, the creditor only provides the capital yet is guaranteed a fixed amount of profit. The debtor, however, puts in time and effort, but is made to bear the risk of loss. Muslim scholars argue that such practice is unjust. As an alternative to usury, Islam strongly encourages charity and direct investment in which the creditor shares whatever profit or loss the business may incur (in modern terms, this amounts to an equity stake in the business).Interest-free micro-lending

Growth of theInternet

The Internet (or internet) is the Global network, global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a internetworking, network of networks ...

internationally has enabled both commercial micro-lending (through sites such as Kickstarter

Kickstarter, PBC is an American Benefit corporation, public benefit corporation based in Brooklyn, New York City, that maintains a global crowdfunding platform focused on creativity. The company's stated mission is to "help bring creative project ...

– launched in 2009) and global micro-lending charities (where lenders make small sums of money available on zero-interest terms). Persons lending money to on-line micro-lending charity Kiva (founded in 2005), for example, do not get paid any interest, although Kiva's partners in the country where the loan is used may charge interest to the end-users to whom the loans are made.

Non-recourse mortgages

A non-recourse loan is secured by the value of property (usually real estate) owned by the debtor. However, unlike other loans, which oblige the debtor to repay the amount borrowed, a non-recourse loan is fully satisfied merely by the transfer of the property to the creditor, even if the property has declined in value and is worth less than the amount borrowed. When such a loan is created, the creditor bears the risk that the property will decline sharply in value (in which case the creditor is repaid with property worth less than the amount borrowed), and the debtor does not bear the risk of decrease in property value (because the debtor is guaranteed the right to use the property, regardless of value, to satisfy the debt.)Zinskauf

Zinskauf was a financial instrument, similar to an annuity, that rose to prominence in the Middle Ages. The decline of the Byzantine Empire led to a growth of capital in Europe, so the Catholic Church tolerated zinskauf as a way to avoid prohibitions on usury. Since zinskauf was an exchange of a fixed amount of money for annual income it was considered a sale rather than a loan. Martin Luther made zinskauf a subject of his Treatise on Usury and his Sermon on Trade and Usury and criticized clerics of the Catholic Church for violating the spirit if not the letter of usury laws.See also

* Chrematistics * Christian finance * Contractum trinius * Debt-trap diplomacy *Greed

Greed (or avarice, ) is an insatiable desire for material gain (be it food, money, land, or animate/inanimate possessions) or social value, such as status or power.

Nature of greed

The initial motivation for (or purpose of) greed and a ...

* History of banking

The history of banking began with the first prototype banks, that is, the merchants of the world, who gave grain loans to farmers and traders who carried goods between cities. This was around 2000 BCE in Assyria, India and Sumer. Later, in a ...

* History of pawnbroking

* Loansharking (traditional occupation of Mafiosi)

* Money changing

* Payday loan

A payday loan (also called a payday advance, salary loan, payroll loan, small dollar loan, short term, or cash advance loan) is a short-term unsecured loan, often characterized by high interest rates. These loans are typically designed to cover ...

s

* Predatory lending

Predatory lending refers to unethical practices conducted by lending organizations during a loan origination process that are unfair, deceptive, or fraudulent. While there are no internationally agreed legal definitions for predatory lending, a 20 ...

* Credit card interest

Credit card interest is a way in which credit card issuers generate revenue. A card issuer is a bank or credit union that gives a consumer (the cardholder) a card or account number that can be used with various payees to make payments and borro ...

* Title loan

* Usury Act 1660

References

Further reading

* * * Dorin, Rowan (2023). ''No Return: Jews, Christian Usurers, and the Spread of Mass Expulsion in Medieval Europe''. Princeton University Press. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Koehler, B. (2023)The Talmud on usury

Economic Affairs, 43(3), 423–435.

External links

What Love Is This? A Renunciation of the Economics of Calvinism

The House of Degenhart.

S.C. Mooney's Response to Dr. Gary North's critique of Usury: Destroyer of Nations

Heretical.com

{{Debt Usury, Medieval economic history Economic bubbles Property crimes Negative Mitzvoth