De Architectura on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

(''On architecture'', published as ''Ten Books on Architecture'') is a treatise on

(''On architecture'', published as ''Ten Books on Architecture'') is a treatise on

Vitruvius sought to address the ethos of architecture, declaring that quality depends on the social relevance of the artist's work, not on the form or workmanship of the work itself. Perhaps the most famous declaration from is one still quoted by architects: "Well building hath three conditions: firmness, commodity, and delight". This quote is taken from Sir

Vitruvius sought to address the ethos of architecture, declaring that quality depends on the social relevance of the artist's work, not on the form or workmanship of the work itself. Perhaps the most famous declaration from is one still quoted by architects: "Well building hath three conditions: firmness, commodity, and delight". This quote is taken from Sir

(I.iii.2)

but English has changed since then, especially in regard to the word "

He advised that

He advised that

Vitruvius described the construction of the

Vitruvius described the construction of the

Vitruvius outlined the many innovations made in building design to improve the living conditions of the inhabitants. Foremost among them is the development of the

Vitruvius outlined the many innovations made in building design to improve the living conditions of the inhabitants. Foremost among them is the development of the

Vitruvius's work was "rediscovered" in 1416 by the Florentine

Vitruvius's work was "rediscovered" in 1416 by the Florentine

(''On architecture'', published as ''Ten Books on Architecture'') is a treatise on

(''On architecture'', published as ''Ten Books on Architecture'') is a treatise on architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

written by the Roman architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs, and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in ...

, as a guide for building projects. As the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity, it has been regarded since the Renaissance as the first known book on architectural theory, as well as a major source on the canon of classical architecture

Classical architecture typically refers to architecture consciously derived from the principles of Ancient Greek architecture, Greek and Ancient Roman architecture, Roman architecture of classical antiquity, or more specifically, from ''De archit ...

.

It contains a variety of information on Greek and Roman buildings, as well as prescriptions for the planning and design of military camps, cities, and structures both large (aqueducts, buildings, baths, harbours) and small (machines, measuring devices, instruments). Since Vitruvius wrote early in the Roman architectural revolution that saw the full development of cross vaulting, domes, concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of aggregate bound together with a fluid cement that cures to a solid over time. It is the second-most-used substance (after water), the most–widely used building material, and the most-manufactur ...

, and other innovations associated with Imperial Roman architecture, his ten books give little information on these distinctive innovations of Roman building design and technology.

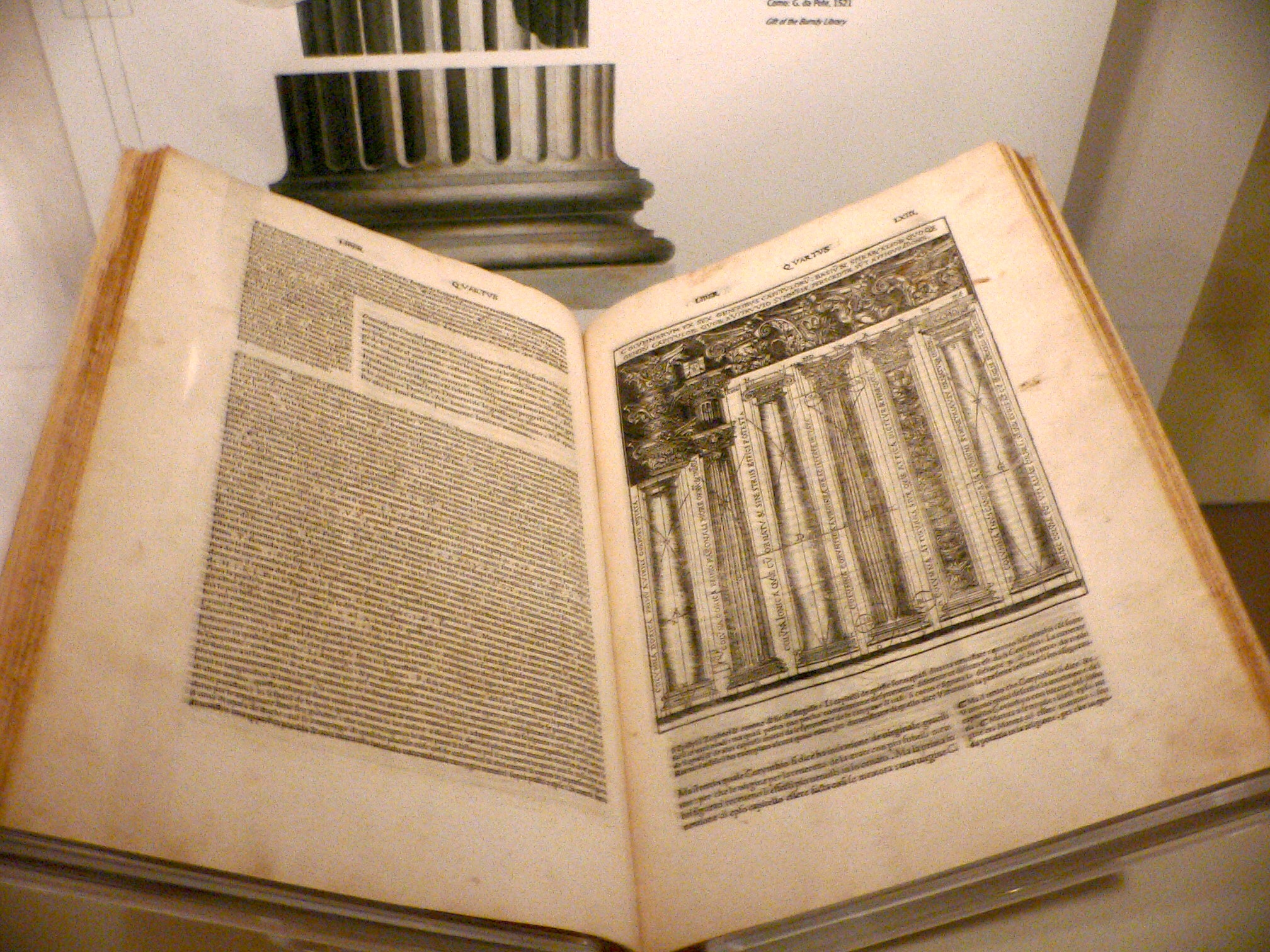

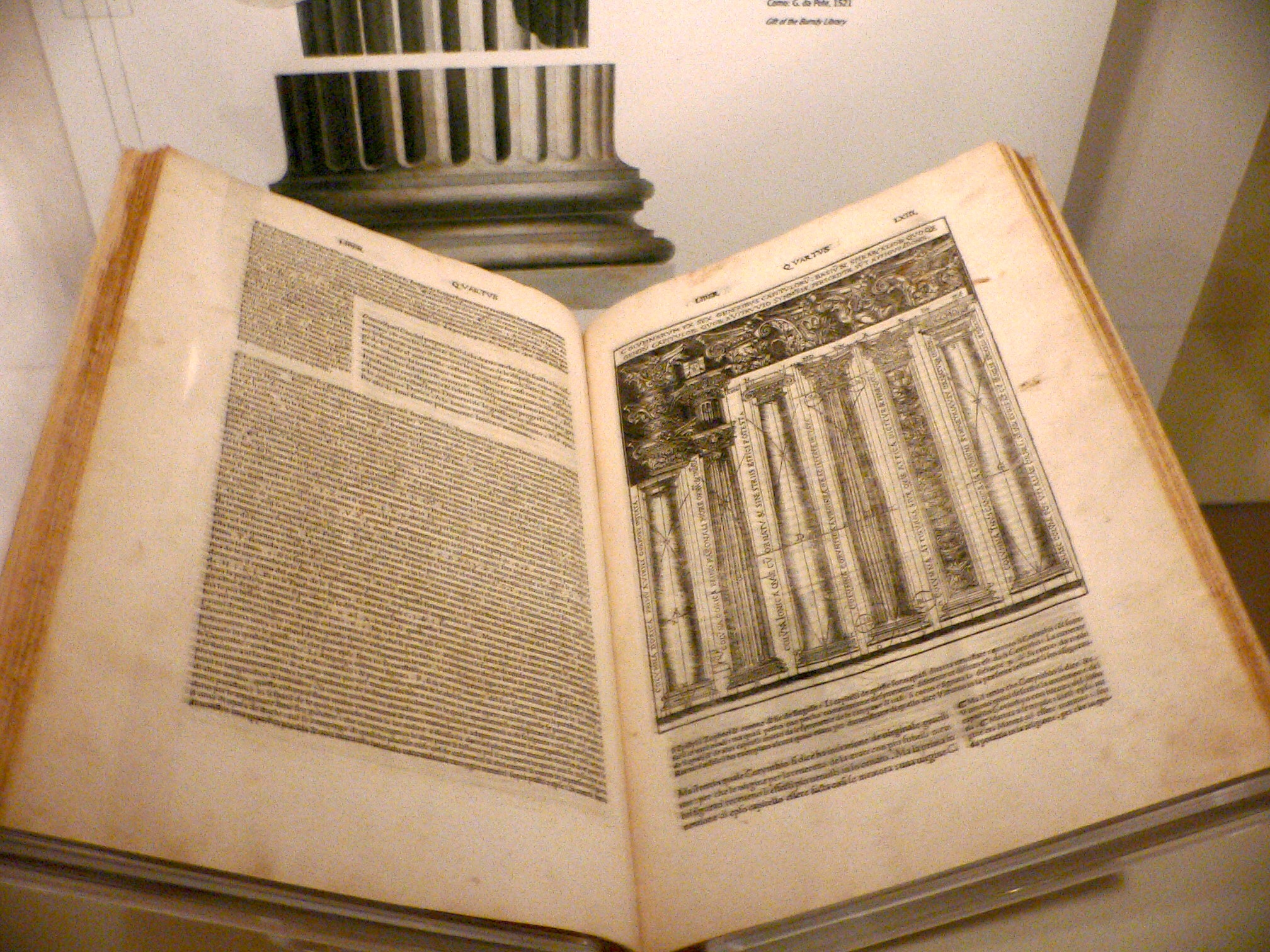

From references to them in the text, it is known that there were at least a few illustrations in original copies (perhaps eight or ten), but perhaps only one of these survived in any medieval manuscript copy. This deficiency was remedied in 16th-century printed editions, which became illustrated with many large plates.

Copies were made during the Carolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. Charlemagne's reign led to an intellectual revival beginning in the 8th century and continuing throughout the 9th ...

, but little use was made of them until the 15th century, when the work became of great interest and influence, initially in Italy and then in the rest of Europe.

Origin and contents

Probably written between 30–20 BC, it combines the knowledge and views of many antique writers, Greek and Roman, on architecture, the arts, natural history and building technology. Vitruvius cites many authorities throughout the text, often praising Greek architects for their development of temple building and the orders ( Doric, Ionic and Corinthian), and providing key accounts of the origins of building in the primitive hut. Though often cited for his famous "triad" of characteristics associated with architectureutilitas, firmitas and venustas (utility, strength and beauty)the aesthetic principles that influenced later treatise writers were outlined in Book III. Derived partially from Latin rhetoric (through Cicero and Varro), Vitruvian terms for order, arrangement, proportion, and fitness for intended purposes have guided architects for centuries, and continue to do so. The Roman author gives advice on the qualifications of an architect (Book I) and on types of architectural drawing. The ten books or scrolls are organized as follows: – '' Ten Books on Architecture'' Roman architects were skilled in engineering, art, and craftsmanship combined. Vitruvius was very much of this type, a fact reflected in . He covered a wide variety of subjects he saw as touching on architecture. This included many aspects that may seem irrelevant to modern eyes, ranging from mathematics to astronomy, meteorology, and medicine. In the Roman conception, architecture needed to take into account everything touching on the physical and intellectual life of man and his surroundings. Vitruvius, thus, deals with many theoretical issues concerning architecture. For instance, in Book of , he advises architects working with bricks to familiarise themselves with pre-Socratic theories of matter so as to understand how their materials will behave. Book relates the abstractgeometry

Geometry (; ) is a branch of mathematics concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. Geometry is, along with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. A mathematician w ...

of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

to the everyday work of the surveyor. Astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

is cited for its insights into the organisation of human life, while astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

is required for the understanding of sundial

A sundial is a horology, horological device that tells the time of day (referred to as civil time in modern usage) when direct sunlight shines by the position of the Sun, apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the ...

s. Likewise, Vitruvius cites Ctesibius of Alexandria and Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

for their inventions, Aristoxenus

Aristoxenus of Tarentum (; born 375, fl. 335 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek Peripatetic school, Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have been lost, but one musi ...

(Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's apprentice) for music, Agatharchus for theatre, and Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BCE) was a Roman polymath and a prolific author. He is regarded as ancient Rome's greatest scholar, and was described by Petrarch as "the third great light of Rome" (after Virgil and Cicero). He is sometimes call ...

for architecture.

Buildings

Vitruvius sought to address the ethos of architecture, declaring that quality depends on the social relevance of the artist's work, not on the form or workmanship of the work itself. Perhaps the most famous declaration from is one still quoted by architects: "Well building hath three conditions: firmness, commodity, and delight". This quote is taken from Sir

Vitruvius sought to address the ethos of architecture, declaring that quality depends on the social relevance of the artist's work, not on the form or workmanship of the work itself. Perhaps the most famous declaration from is one still quoted by architects: "Well building hath three conditions: firmness, commodity, and delight". This quote is taken from Sir Henry Wotton

Sir Henry Wotton (; 30 March 1568 – December 1639) was an English author, diplomat and politician who sat in the House of Commons of England, House of Commons in 1614 and 1625. When on a mission to Augsburg in 1604, he famously said "An amba ...

's version of 1624, and accurately translates the passage in the work(I.iii.2)

but English has changed since then, especially in regard to the word "

commodity

In economics, a commodity is an economic goods, good, usually a resource, that specifically has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the Market (economics), market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to w ...

", and the tag may be misunderstood. In modern English it would read: "The ideal building has three elements; it is sturdy, useful, and beautiful."

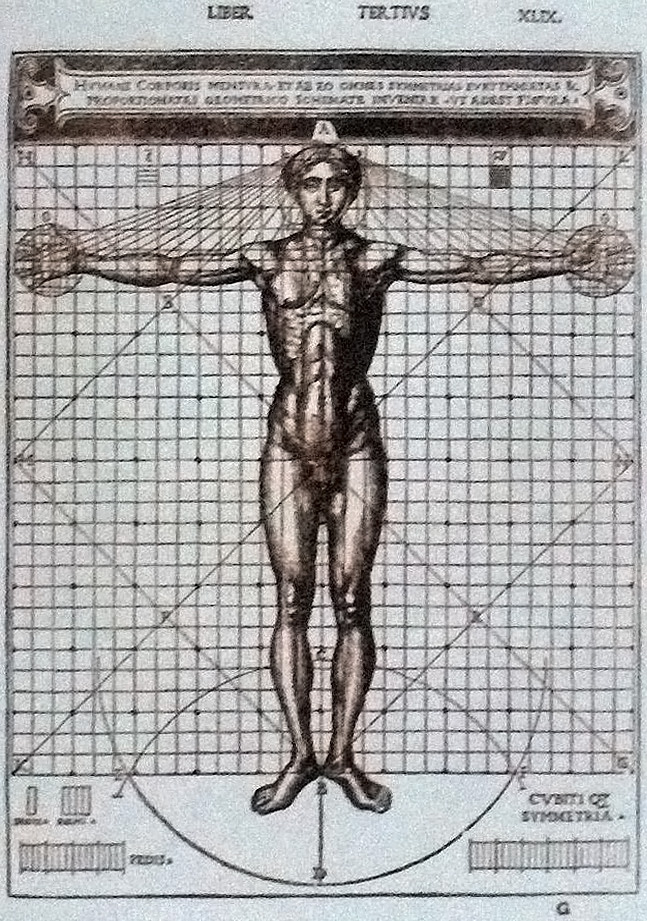

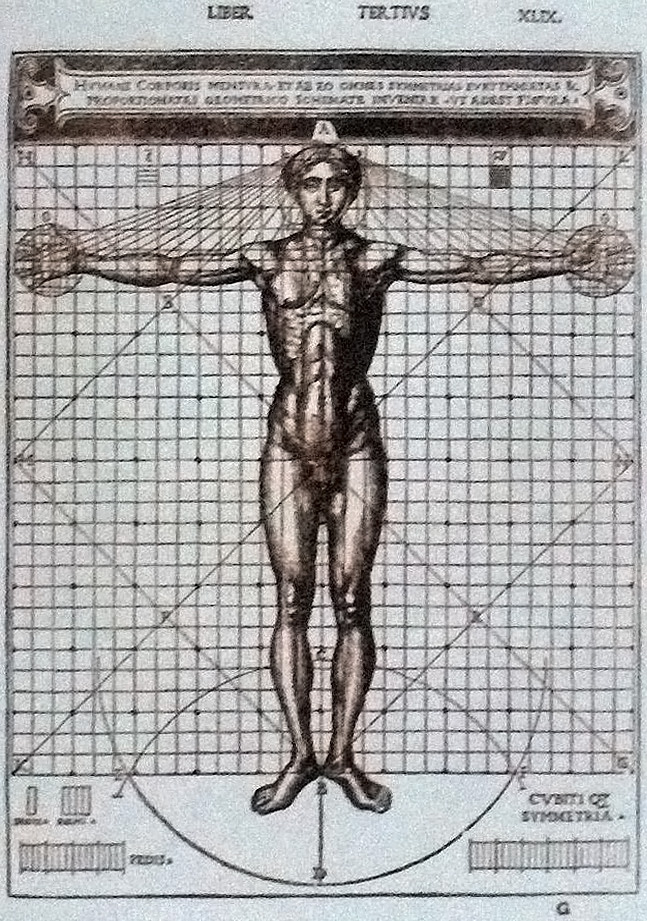

Vitruvius also studied human proportions (Book ) and this part of his ''canones'' were later adopted and adapted in the famous drawing (" Vitruvian Man") by Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 - 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested o ...

.

Domestic architecture

While Vitruvius is fulsome in his descriptions of religious buildings, infrastructure and machinery, he gives a mixed message on domestic architecture. Similar to Aristotle, Vitruvius offers admiration for householders who built their own homes without the involvement of an architect. His ambivalence on domestic architecture is most clearly read in the opening paragraph of the Introduction to Book 6. Book 6 focusses exclusively on residential architecture but as architectural theorist Simon Weir has explained, instead of writing the introduction on the virtues of residences or the family or some theme related directly to domestic life; Vitruvius writes an anecdote about the Greek ethical principle ofxenia

Xenia may refer to:

People

* Xenia (name), a feminine given name; includes a list of people with this name

Places United States

''listed alphabetically by state''

* Xenia, Illinois, a village in Clay County

** Xenia Township, Clay County, Il ...

: showing kindness to strangers.

Roman technology

is important for its descriptions of many different machines used for engineering structures, such as hoists, cranes, and pulleys, as well as war machines such ascatapult

A catapult is a ballistics, ballistic device used to launch a projectile at a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden rel ...

s, ballistae, and siege engines. Vitruvius also described the construction of sundials and water clocks, and the use of an aeolipile (the first steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs Work (physics), mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a Cylinder (locomotive), cyl ...

) as an experiment to demonstrate the nature of atmospheric air movements (wind).

Aqueducts and mills

Books , , and of form the basis of much of what is known about Roman technology, now augmented by archaeological studies of extant remains, such as the Pont du Gard in southern France. Numerous such massive structures occur across the former empire, a testament to the power of Roman engineering. Vitruvius's description of Roman aqueduct construction is short, but mentions key details especially for the way they were surveyed, and the careful choice of materials needed. His book would have been of assistance to Frontinus, a general who was appointed in the late 1st century AD to administer the many aqueducts of Rome. Frontinus wrote , the definitive treatise on 1st-century Roman aqueducts, and discovered a discrepancy between the intake and supply of water caused by illegal pipes inserted into the channels to divert the water. The Roman Empire went far in exploiting water power, as the set of no fewer than 16water mill

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in the production ...

s at Barbegal in France demonstrates. The mills ground grain in a very efficient operation, and many other mills are now known, such as the much later Hierapolis sawmill.

Materials

Vitruvius described many different construction materials used for a wide variety of different structures, as well as such details asstucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and ...

painting. Cement

A cement is a binder, a chemical substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. Cement is seldom used on its own, but rather to bind sand and gravel ( aggregate) together. Cement mi ...

, concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of aggregate bound together with a fluid cement that cures to a solid over time. It is the second-most-used substance (after water), the most–widely used building material, and the most-manufactur ...

, and lime received in-depth descriptions, the longevity of many Roman structures being mute testimony to their skill in building materials and design.

He advised that

He advised that lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

should not be used to conduct drinking water, clay pipes being preferred. He comes to this conclusion in Book of after empirical observation of the apparent laborer illnesses in the (lead pipe) foundries of his time. However, much of the water used by Rome and many other cities was very hard, minerals soon coated the inner surfaces of the pipes, so lead poisoning

Lead poisoning, also known as plumbism and saturnism, is a type of metal poisoning caused by lead in the body. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, constipation, headaches, irritability, memory problems, infertility, numbness and paresthesia, t ...

was reduced.

Vitruvius related the famous story about Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

and his detection of adulterated gold in a royal crown. When Archimedes realized the volume of the crown could be measured exactly by the displacement created in a bath of water, he ran into the street with the cry of " Eureka!", and the discovery enabled him to compare the density of the crown with pure gold. He showed the crown had been alloyed with silver, and the king was defrauded.

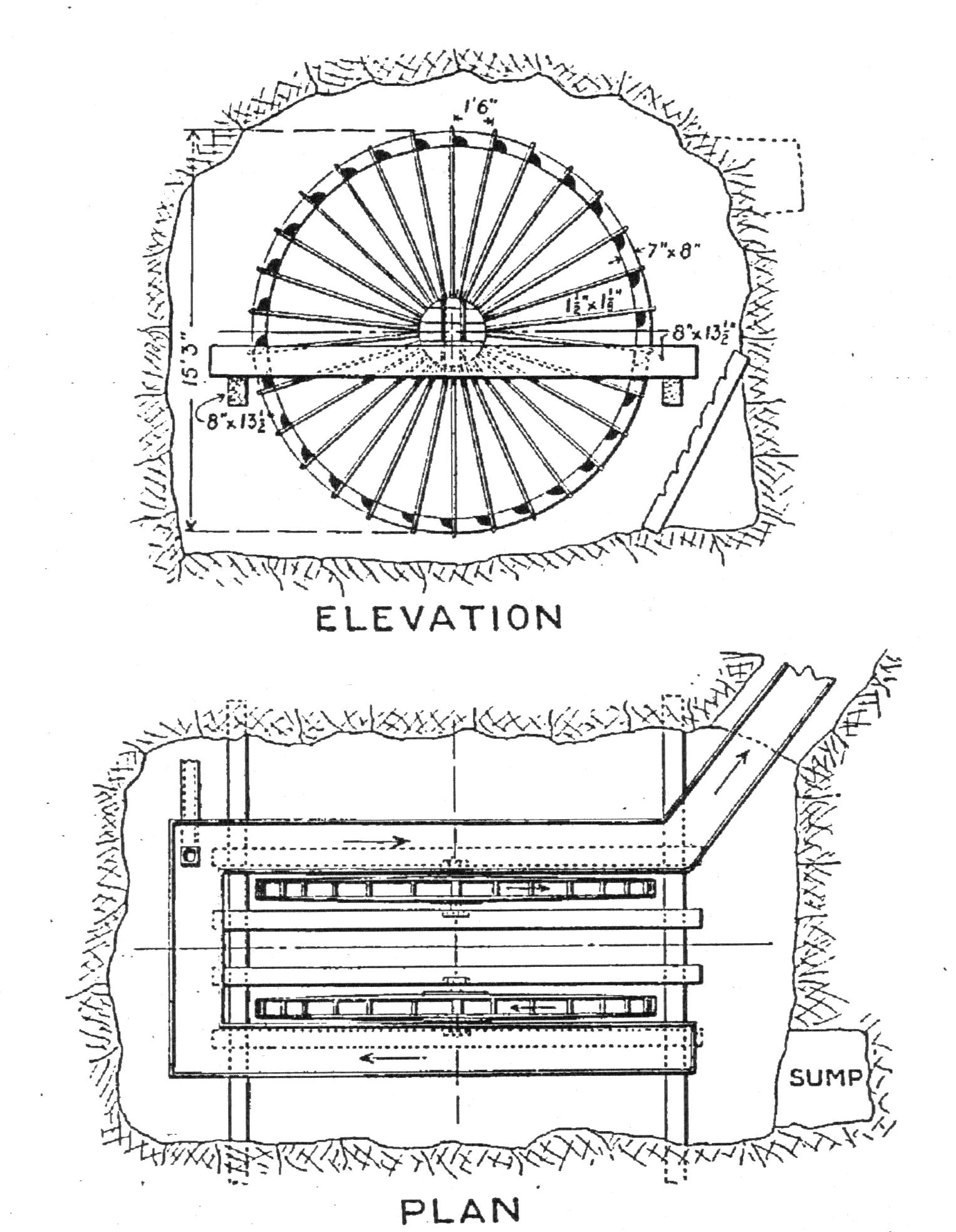

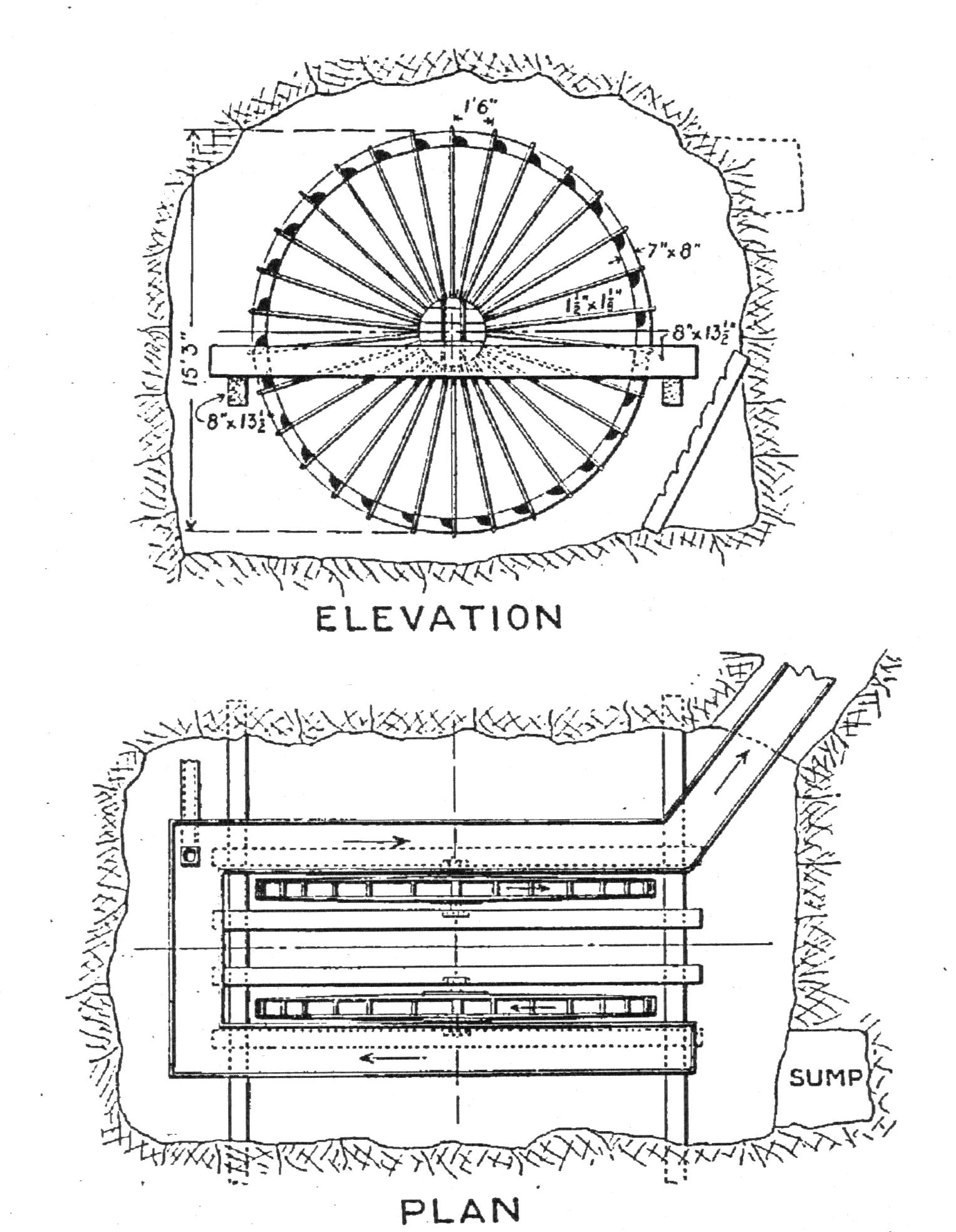

Dewatering machines

Vitruvius described the construction of the

Vitruvius described the construction of the Archimedes' screw

The Archimedes' screw, also known as the Archimedean screw, hydrodynamic screw, water screw or Egyptian screw, is one of the earliest documented hydraulic machines. It was so-named after the Greek mathematician Archimedes who first described it ...

in Chapter 10, although did not mention Archimedes by name. It was a device widely used for raising water to irrigate fields and dewater mines. Other lifting machines mentioned in include the endless chain of buckets and the reverse overshot water-wheel. Remains of the water wheels used for lifting water have been discovered in old mines such as those at Rio Tinto in Spain and Dolaucothi in west Wales. One of the wheels from Rio Tinto is now in the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

, and one from the latter in the National Museum of Wales. The remains were discovered when these mines were reopened in modern mining attempts. They would have been used in a vertical sequence, with 16 such mills capable of raising water at least above the water table. Each wheel would have been worked by a miner treading the device at the top of the wheel, by using cleats on the outer edge. That they were using such devices in mines clearly implies that they were entirely capable of using them as water wheels

A water wheel is a machine for converting the kinetic energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a large wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with numerous blade ...

to develop power for a range of activities, not just for grinding wheat, but also probably for sawing timber, crushing ores, fulling

Fulling, also known as tucking or walking ( Scots: ''waukin'', hence often spelt waulking in Scottish English), is a step in woollen clothmaking which involves the cleansing of woven cloth (particularly wool) to eliminate ( lanolin) oils, ...

, and so on.

Force pump

Ctesibius is credited with the invention of theforce pump

A piston pump is a type of positive displacement pump where the high-pressure seal reciprocates with the piston. Piston pumps can be used to move liquids or compress gases. They can operate over a wide range of pressures. High pressure operation ...

, which Vitruvius described as being built from bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

with valves to allow a head of water to be formed above the machine. The device is also described by Hero of Alexandria

Hero of Alexandria (; , , also known as Heron of Alexandria ; probably 1st or 2nd century AD) was a Greek mathematician and engineer who was active in Alexandria in Egypt during the Roman era. He has been described as the greatest experimental ...

in his . The machine is operated by hand in moving a lever up and down. He mentioned its use for supplying fountains above a reservoir, although a more mundane use might be as a simple fire engine. One was found at Calleva Atrebatum ( Roman Silchester) in England, and another is on display at the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

. Their functions are not described, but they are both made in bronze, just as Vitruvius specified.

Vitruvius also mentioned the several automaton

An automaton (; : automata or automatons) is a relatively self-operating machine, or control mechanism designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations, or respond to predetermined instructions. Some automata, such as bellstrikers i ...

s Ctesibius invented, and intended for amusement and pleasure rather than serving a useful function.

Central heating

Vitruvius outlined the many innovations made in building design to improve the living conditions of the inhabitants. Foremost among them is the development of the

Vitruvius outlined the many innovations made in building design to improve the living conditions of the inhabitants. Foremost among them is the development of the hypocaust

A hypocaust () is a system of central heating in a building that produces and circulates hot air below the floor of a room, and may also warm the walls with a series of pipes through which the hot air passes. This air can warm the upper floors a ...

, a type of central heating

A central heating system provides warmth to a number of spaces within a building from one main source of heat.

A central heating system has a Furnace (central heating), furnace that converts fuel or electricity to heat through processes. The he ...

where hot air developed by a fire was channelled under the floor and inside the walls of public baths and villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house that provided an escape from urban life. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the f ...

s. He gave explicit instructions on how to design such buildings so fuel efficiency

Fuel efficiency (or fuel economy) is a form of thermal efficiency, meaning the ratio of effort to result of a process that converts chemical energy, chemical potential energy contained in a carrier (fuel) into kinetic energy or Mechanical work, w ...

is maximized; for example, the is next to the followed by the . He also advised using a type of regulator to control the heat in the hot rooms, a bronze disc set into the roof under a circular aperture, which could be raised or lowered by a pulley to adjust the ventilation. Although he did not suggest it himself, his dewatering devices such as the reverse overshot water-wheel likely were used in the larger baths to lift water to header tanks at the top of the larger , such as the Baths of Diocletian

The Baths of Diocletian (Latin: ''Thermae Diocletiani'', Italian: ''Terme di Diocleziano'') were public baths in ancient Rome. Named after emperor Diocletian and built from AD 298 to 306, they were the largest of the imperial baths. The project w ...

and the Baths of Caracalla

The Baths of Caracalla () in Rome, Italy, were the city's second largest Ancient Rome, Roman public baths, or ''thermae'', after the Baths of Diocletian. The baths were likely built between AD 212 (or 211) and 216/217, during the reigns of empero ...

.

Surveying instruments

That Vitruvius must have been well practised in surveying is shown by his descriptions of surveying instruments, especially the water level or , which he compared favourably with the , a device usingplumb line

A plumb bob, plumb bob level, or plummet, is a weight, usually with a pointed tip on the bottom, suspended from a string and used as a vertical direction as a reference line, or plumb-line. It is a precursor to the spirit level and used to est ...

s. They were essential in all building operations, but especially in aqueduct construction, where a uniform gradient was important to provision of a regular supply of water without damage to the walls of the channel. He described the , in essence a device for automatically measuring distances along roads, a machine essential for developing accurate itineraries, such as the Peutinger Table

' (Latin for 'The Peutinger Map'), also known as Peutinger's Tabula, Peutinger tables James Strong and John McClintock (1880)"Eleutheropolis" In: ''The Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature''. NY: Haper and Brothers ...

.

Sea level change

In Book Chapter 1 Subsection 4 of is a description of 13Athenian

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

cities in Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, "the land of Caria

Caria (; from Greek language, Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; ) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Carians were described by Herodotus as being Anatolian main ...

", in present-day Turkey. These cities are given as: Ephesus

Ephesus (; ; ; may ultimately derive from ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia, in present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital ...

, Miletus

Miletus (Ancient Greek: Μίλητος, Mílētos) was an influential ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in present day Turkey. Renowned in antiquity for its wealth, maritime power, and ex ...

, Myus, Priene, Samos

Samos (, also ; , ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese archipelago, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the Mycale Strait. It is also a separate reg ...

, Teos, Colophon, Chius, Erythrae, Phocaea, Clazomenae

Klazomenai () or Clazomenae was one of the 12 cities of ancient Ionia (the others being Chios, Samos, Phocaea, Erythrae, Teos, Lebedus, Colophon, Ephesus, Priene, Myus, and Miletus). It is located at the south coast of Smyrna Gulf, Ion ...

, Lebedos, Mytilene

Mytilene (; ) is the capital city, capital of the Greece, Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University of the Aegean. It was fo ...

, and later a 14th, Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

eans. Myus, the third city, is described as being "long ago engulfed by the water, and its sacred rites and suffrage". This sentence indicates, at the time of Vitruvius's writing, it was known that sea-level change and/or land subsidence

Subsidence is a general term for downward vertical movement of the Earth's surface, which can be caused by both natural processes and human activities. Subsidence involves little or no horizontal movement, which distinguishes it from slope mov ...

occurred. The layout of these cities is in general from south to north so that it appears that where Myrus should be located is inland. If this is the case, then since the writing of , the region has experienced either soil rebound or a sea-level fall. Though not indicative of sea-level change, or speculation of such, during the later-empire many Roman ports suffered from what contemporary writers described as 'silting'. The constant need to dredge ports became a heavy burden on the treasury and some have speculated that this expense significantly contributed to the eventual collapse of the empire. Roman salt works in Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

, England, today are located at the five-metre contour, implying this was the coastline. These observations only indicate the extent of silting and soil rebound affecting coastline change since the writing of .

Survival and rediscovery

Manuscripts

Vitruvius's work is one of many examples of Latin texts that owe their survival to the palace ofCharlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

in the early 9th century. This activity of finding and recopying classical manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand or typewritten, as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in some indirect or automated way. More recently, the term has ...

s is part of what is called the Carolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. Charlemagne's reign led to an intellectual revival beginning in the 8th century and continuing throughout the 9th ...

. The London Vitruvius ( British Library, Harley 2767), the oldest surviving manuscript, includes only one of the original illustrations, a rather crudely drawn octagonal wind rose in the margin. This was written in Germany in about 800 to 825, probably at the abbey of Saint Pantaleon, Cologne, and has been shown to be one of the most important manuscripts for the further transmission of the text.

These texts were not just copied, but also known at the court of Charlemagne, since his historian, bishop Einhard

Einhard (also Eginhard or Einhart; ; 775 – 14 March 840) was a Franks, Frankish scholar and courtier. Einhard was a dedicated servant of Charlemagne and his son Louis the Pious; his main work is a biography of Charlemagne, the ''Vita Karoli M ...

, asked the visiting English churchman Alcuin

Alcuin of York (; ; 735 – 19 May 804), also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin, was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student of Ecgbert of York, Archbishop Ecgbert at Yor ...

for explanations of some technical terms. In addition, a number of individuals are known to have read the text or have been indirectly influenced by it, including: Vussin, Hrabanus Maurus, Hermann of Reichenau, Hugo of St. Victor, Gervase of Melkley, William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury (; ) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as "a gifted historical scholar and a ...

, Theodoric of Sint-Truiden, Petrus Diaconus, Albertus Magnus, Filippo Villani, Jean de Montreuil, Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

, Boccaccio, Giovanni de Dondi, Domenico Bandini, Niccolò Acciaioli

Niccolò Acciaioli or Acciaiuoli (1310 – 8 November 1365) was an Italian noble, a member of the Florence, Florentine banking family of the Acciaioli. He was the grand seneschal of the Kingdom of Naples and count of Melfi, Count of Malta, Ma ...

bequeathed copy to the Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence, Bernward of Hildesheim, and Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

. In 1244 the Dominican friar Vincent of Beauvais made a large number of references to in his compendium of all the knowledge of the Middle Ages

Many copies of , dating from the 8th to the 15th centuries, did exist in manuscript form during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

and 92 are still available in public collections, but they appear to have received little attention, possibly due to the obsolescence of many specialized Latin terms used by Vitruvius and the loss of most of the original 10 illustrations thought by some to be helpful in understanding parts of the text.

Vitruvius's work was "rediscovered" in 1416 by the Florentine

Vitruvius's work was "rediscovered" in 1416 by the Florentine humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

Poggio Bracciolini

Gian Francesco Poggio Bracciolini (; 11 February 1380 – 30 October 1459), usually referred to simply as Poggio Bracciolini, was an Italian scholar and an early Renaissance humanism, Renaissance humanist. He is noted for rediscovering and recove ...

, who found it in the Abbey library of Saint Gall

The Abbey library of St Gall () is a significant medieval monastic library located in St. Gallen, Switzerland. In 1983, the library, as well as the Abbey of St Gall, were designated a World Heritage Site, as "an outstanding example of a large Caro ...

, Switzerland. He publicized the manuscript to a receptive audience of Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

thinkers, just as interest in the classical cultural and scientific heritage was reviving.

Printed editions

The first printed edition (), an version, was published by the Veronese scholar Fra Giovanni Sulpitius in 1486 (with a second edition in 1495 or 1496), but none were illustrated. The Dominican friar Fra Giovanni Giocondo produced the first version illustrated with woodcuts inVenice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

in 1511. It had a thorough philosophical approach and superb illustrations.

Translations into Italian were in circulation by the 1520s, the first in print being the translation with new illustrations by Cesare Cesariano, a Milanese friend of the architect Bramante, printed in Como in 1521. It was rapidly translated into other European languagesthe first French version was published in 1547and the first German version followed in 1548. The first Spanish translation was published in 1582 by Miguel de Urrea and Juan Gracian. The most authoritative and influential edition was publicized in French in 1673 by Claude Perrault

Claude Perrault (; 25 September 1613 – 9 October 1688) was a French physician and amateur architect, best known for his participation in the design of the east façade of the Louvre in Paris.Jean-Baptiste Colbert in 1664.

John Shute had drawn on the text as early as 1563 for his book ''The First and Chief Grounds of Architecture''. Sir

The rediscovery of Vitruvius's work had a profound influence on architects of the

The rediscovery of Vitruvius's work had a profound influence on architects of the

The ''Ten Books of Architecture'' online: cross-linked Latin text and English translation

''The Ten Books on Architecture''

at the Perseus Classics Collection. Latin and English text. Latin text has hyperlinks to pop-up dictionary.

(Morris Hicky Morgan translation with illustrations) *

Modern bibliography on line (15th-17th centuries)

* Vitruvii, M

Naples, . A

Somni

digital scans in high resolution of 73 editions of Vitruvius from 1497 to 1909

from th

Werner Oechslin Library, Einsiedeln, Switzerland

{{Authority control 1st-century BC books in Latin Ancient Roman architecture Ancient Roman military technology Ancient Roman siege warfare Architectural treatises Civil engineering Construction Military books in Latin Military engineering Roman siege engines Prose texts in Latin Technology books de:Vitruv#Werk

Henry Wotton

Sir Henry Wotton (; 30 March 1568 – December 1639) was an English author, diplomat and politician who sat in the House of Commons of England, House of Commons in 1614 and 1625. When on a mission to Augsburg in 1604, he famously said "An amba ...

's 1624 work ''The Elements of Architecture'' amounts to a heavily-influenced adaptation, while a 1692 translation was much abridged. English-speakers had to wait until 1771 for a full translation of the first five volumes and 1791 for the whole thing. Thanks to the art of printing, Vitruvius's work had become a popular subject of hermeneutics

Hermeneutics () is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts. As necessary, hermeneutics may include the art of understanding and communication.

...

, with highly detailed and interpretive illustrations, and became widely dispersed.

Of the many later editions, the 1914 ''Ten Books on Architecture'' translated by Morris H. Morgan, Ph.D, LL.D. Late Professor of Classical Philology in Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

, is fully available at ''Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg (PG) is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the oldest digital li ...

'', and from the Internet Archive.

Impact

The rediscovery of Vitruvius's work had a profound influence on architects of the

The rediscovery of Vitruvius's work had a profound influence on architects of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, prompting the rebirth of Classical architecture in subsequent centuries. Renaissance architects, such as Niccoli, Brunelleschi

Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi (1377 – 15 April 1446), commonly known as Filippo Brunelleschi ( ; ) and also nicknamed Pippo by Leon Battista Alberti, was an Italian architect, designer, goldsmith and sculptor. He is considered to ...

and Leon Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti (; 14 February 1404 – 25 April 1472) was an Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, Catholic priest, priest, linguistics, linguist, philosopher, and cryptography, cryptographer; he epitomised the natu ...

, found in their rationale for raising their branch of knowledge to a scientific discipline as well as emphasising the skills of the artisan

An artisan (from , ) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by hand. These objects may be functional or strictly decorative, for example furniture, decorative art, sculpture, clothing, food ite ...

. One of Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 - 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested o ...

's best known drawings, the '' Vitruvian Man'', is based on the principles of body proportions developed by Vitruvius in the first chapter of Book III, ''On Symmetry: In Temples And In The Human Body''.

The English architect Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was an English architect who was the first significant Architecture of England, architect in England in the early modern era and the first to employ Vitruvius, Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmet ...

and the Frenchman Salomon de Caus were among the first to re-evaluate and implement those disciplines that Vitruvius considered a necessary element of architecture: arts and science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

s based upon number and proportion. The 16th-century architect Palladio considered Vitruvius his master and guide, and made some drawings based on his work before conceiving his own architectural precepts.

Astrolabe

The earliest evidence of use of thestereographic projection

In mathematics, a stereographic projection is a perspective transform, perspective projection of the sphere, through a specific point (geometry), point on the sphere (the ''pole'' or ''center of projection''), onto a plane (geometry), plane (th ...

in a machine is in , which describes an anaphoric clock (it is presumed, a or water clock) in Alexandria. The clock had a rotating field of stars behind a wire frame indicating the hours of the day. The wire framework (the spider) and the star locations were constructed using the stereographic projection. Similar constructions dated from the 1st to 3rd centuries have been found in Salzburg and northeastern France, so such mechanisms were, it is presumed, fairly widespread among Romans.

See also

* by Leon Battista Alberti * * * * *References

Further reading

*B. Baldwin: ''The Date, Identity, and Career of Vitruvius''. In: Latomus 49 (1990), 425–34 *I. Rowland, T.N. Howe: ''Vitruvius. Ten Books on Architecture''. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1999,External links

The ''Ten Books of Architecture'' online: cross-linked Latin text and English translation

''The Ten Books on Architecture''

at the Perseus Classics Collection. Latin and English text. Latin text has hyperlinks to pop-up dictionary.

(Morris Hicky Morgan translation with illustrations) *

Modern bibliography on line (15th-17th centuries)

* Vitruvii, M

Naples, . A

Somni

digital scans in high resolution of 73 editions of Vitruvius from 1497 to 1909

from th

Werner Oechslin Library, Einsiedeln, Switzerland

{{Authority control 1st-century BC books in Latin Ancient Roman architecture Ancient Roman military technology Ancient Roman siege warfare Architectural treatises Civil engineering Construction Military books in Latin Military engineering Roman siege engines Prose texts in Latin Technology books de:Vitruv#Werk