Dazai Osamu on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, known by his

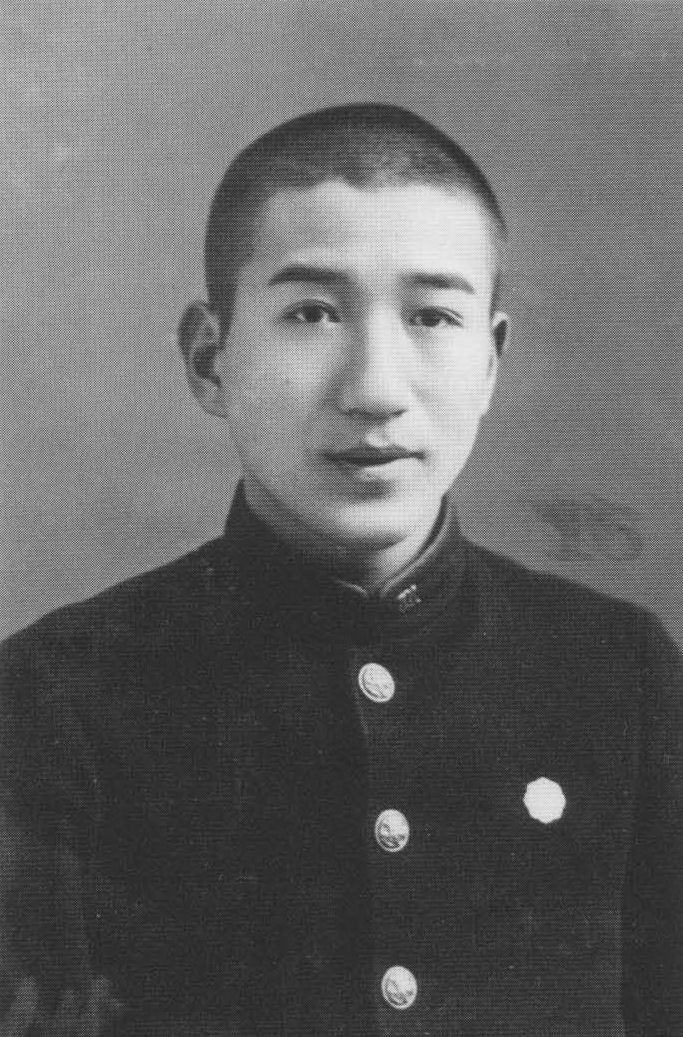

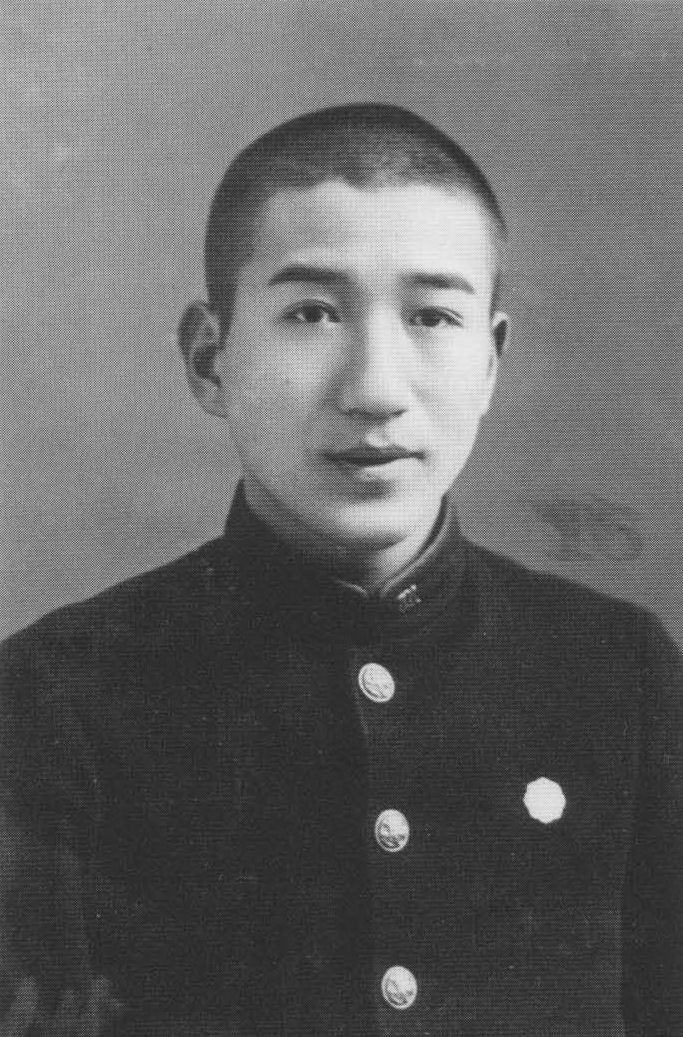

Shūji Tsushima was born on June 19, 1909, the eighth surviving child of a wealthy landowner and politician in Kanagi, located at the northern tip of the

Shūji Tsushima was born on June 19, 1909, the eighth surviving child of a wealthy landowner and politician in Kanagi, located at the northern tip of the

Dazai kept his promise and settled down. He managed to obtain the assistance of

Dazai kept his promise and settled down. He managed to obtain the assistance of

In the immediate postwar period, Dazai reached the height of his popularity. He depicted a dissolute life in postwar Tokyo in ''Viyon no Tsuma'' (ヴィヨンの妻, "Villon's Wife", 1947), depicting the wife of a poet who had abandoned her and her continuing will to live through hardships.

In 1946, Dazai published a controversial memoir, "Kuno no Nenkan" (Almanac of Pain), in which he describes the immediate aftermath of Japan's defeat and seeks to encapsulate how the Japanese felt at the time. Dazai reaffirmed his loyalty to the Japanese Emperor,

In the immediate postwar period, Dazai reached the height of his popularity. He depicted a dissolute life in postwar Tokyo in ''Viyon no Tsuma'' (ヴィヨンの妻, "Villon's Wife", 1947), depicting the wife of a poet who had abandoned her and her continuing will to live through hardships.

In 1946, Dazai published a controversial memoir, "Kuno no Nenkan" (Almanac of Pain), in which he describes the immediate aftermath of Japan's defeat and seeks to encapsulate how the Japanese felt at the time. Dazai reaffirmed his loyalty to the Japanese Emperor,  In July 1947, Dazai's novel ''Shayo'' (''

In July 1947, Dazai's novel ''Shayo'' (''

On June 13, 1948, Dazai and Tomie drowned themselves in the rain-swollen Tamagawa Canal, near his house. Their bodies were not discovered until six days later, on June 19, which would have been his 39th birthday. His grave is at the temple of Zenrin-ji, in

On June 13, 1948, Dazai and Tomie drowned themselves in the rain-swollen Tamagawa Canal, near his house. Their bodies were not discovered until six days later, on June 19, which would have been his 39th birthday. His grave is at the temple of Zenrin-ji, in

Osamu Dazai's works in Japanese

on

Osamu Dazai's grave

at JLPP (Japanese Literature Publishing Project) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Dazai, Osamu 1909 births 1948 suicides 1948 deaths 20th-century Japanese novelists Japanese male short story writers People from the Empire of Japan Writers from Aomori Prefecture University of Tokyo alumni Suicides by drowning in Japan 20th-century Japanese short story writers 20th-century Japanese male writers Joint suicides Aomori High School alumni

pen name

A pen name or nom-de-plume is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen name may be used to make the author's na ...

, was a Japanese novelist and author. A number of his most popular works, such as ''The Setting Sun

is a Japanese novel by Osamu Dazai first published in 1947. The story centers on an aristocratic family in decline and crisis during the early years after World War II.

Plot summary

Twenty-nine-year-old Kazuko, her brother Naoji, and their w ...

'' (斜陽, ''Shayō'') and '' No Longer Human'' (人間失格, ''Ningen Shikkaku''), are considered modern classics.

His influences include Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

, art name , was a Japanese writer active in the Taishō period in Japan. He is regarded as the "father of the Japanese short story", and Japan's premier literary award, the Akutagawa Prize, is named after him. He took his own life at the age ...

, Murasaki Shikibu

was a Japanese novelist, Japanese poetry#Age of Nyobo or court ladies, poet and lady-in-waiting at the Imperial Court in Kyoto, Imperial court in the Heian period. She was best known as the author of ''The Tale of Genji'', widely considered t ...

and Fyodor Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian and world literature, and many of his works are considered highly influent ...

. His last book, ''No Longer Human'', is his most popular work outside of Japan.

Another pseudonym he used was Shunpei Kuroki (黒木 舜平), for the book ''Illusion of the Cliffs'' (断崖の錯覚, ''Dangai no Sakkaku'').

Early life

Shūji Tsushima was born on June 19, 1909, the eighth surviving child of a wealthy landowner and politician in Kanagi, located at the northern tip of the

Shūji Tsushima was born on June 19, 1909, the eighth surviving child of a wealthy landowner and politician in Kanagi, located at the northern tip of the Tōhoku Region

The , Northeast region, , or consists of the northeastern portion of Honshu, the largest island of Japan. This traditional region consists of six prefectures (): Akita, Aomori, Fukushima, Iwate, Miyagi, and Yamagata.

Tōhoku retains ...

, in Aomori Prefecture

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan in the Tōhoku region. The prefecture's capital, largest city, and namesake is the city of Aomori (city), Aomori. Aomori is the northernmost prefecture on Japan's main island, Honshu, and is border ...

. He was the tenth of the eleven children born to his parents. At the time of his birth, the huge, newly completed Tsushima mansion, where he spent his early years, was home to some thirty family members. The Tsushima family was of obscure peasant origins. Dazai's great-grandfather built up the family's wealth as a moneylender, and his son increased it further. They quickly rose in power and, after some time, became highly respected across the region.

Dazai's father, Gen'emon, was a younger son of the Matsuki family, which, due to "its exceedingly 'feudal' tradition," had no use for sons other than the eldest son and heir. As a result, Gen'emon was adopted into the Tsushima family to marry the eldest daughter, Tane. He became involved in politics due to his position as one of the four wealthiest landowners in the prefecture, and was offered membership of the House of Peers. This caused Dazai's father to be absent during much of his early childhood. As his mother, Tane, was ill, Dazai was brought up mostly by the family's servants and his aunt Kiye.

Education and literary beginnings

In 1916, Dazai began his education at Kanagi Elementary. On March 4, 1923, his father Gen'emon died from lung cancer. A month later, in April, Dazai moved to Aomori Junior High School, followed in 1927 by Hirosaki Higher School, auniversity preparatory school

A college-preparatory school (often shortened to prep school, preparatory school, college prep school or college prep academy) is a type of secondary school. The term refers to public, private independent or parochial schools primarily design ...

. He developed an interest in Edo culture and began studying gidayū, a form of chanted narration used in ''bunraku

is a form of traditional Japanese puppet theatre, founded in Osaka in the beginning of the 17th century, which is still performed in the modern day. Three kinds of performers take part in a performance: the or (puppeteers), the (chanters) ...

''. Around 1928, Dazai edited a series of student publications and contributed some of his own works. He also published a magazine called ''Saibō Bungei'' (''Cell Literature'') with his friends, and subsequently became a staff member of the college's newspaper.

Dazai's success in writing was brought to a halt when his idol, the writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

, art name , was a Japanese writer active in the Taishō period in Japan. He is regarded as the "father of the Japanese short story", and Japan's premier literary award, the Akutagawa Prize, is named after him. He took his own life at the age ...

, committed suicide in 1927 at 35 years old. Dazai started to neglect his studies, and spent the majority of his allowance on clothes, alcohol, and prostitutes. He also dabbled in Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

, which at the time was heavily suppressed by the government.

On the night of December 10, 1929, Dazai made his first suicide attempt, but survived and was able to graduate the following year. In 1930, he enrolled in the French Literature

French literature () generally speaking, is literature written in the French language, particularly by French people, French citizens; it may also refer to literature written by people living in France who speak traditional languages of Franc ...

Department of Tokyo Imperial University

The University of Tokyo (, abbreviated as in Japanese and UTokyo in English) is a public university, public research university in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Founded in 1877 as the nation's first modern university by the merger of several Edo peri ...

, but promptly stopped studying again. In October, he ran away with a geisha

{{Culture of Japan, Traditions, Geisha

{{nihongo, Geisha{{efn, {{IPAc-en, lang, ˈ, ɡ, eɪ, ., ʃ, ə, {{IPA, ja, ɡei.ɕa, ɡeː-, lang{{cite book, script-title=ja:NHK日本語発音アクセント新辞典, publisher=NHK Publishing, editor= ...

named and was formally disowned by his family.

Nine days after he was expelled from Tokyo Imperial University, Dazai attempted suicide by drowning off a beach in Kamakura

, officially , is a city of Kanagawa Prefecture in Japan. It is located in the Kanto region on the island of Honshu. The city has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 people per km2 over the tota ...

with another woman, a 19-year-old bar hostess named . Tanabe died, but Dazai lived. He was rescued by the crew of a fishing boat, and was charged as an accomplice in Tanabe's death. Shocked by the events, Dazai's family intervened to stop the police investigation. His allowance was reinstated, and he was released without any charges. In December, he recovered at Ikarigaseki and married Hatsuyo there.

Leftist movement

In 1929, when the principal of Hirosaki High School was found to have misappropriated public funds, the students, under the leadership of Ueda Shigehiko (Ishigami Genichiro), leader of the Social Science Study Group, staged a five-day strike, which resulted in the principal's resignation and no disciplinary action against the students. Dazai hardly participated in the strike, but in imitation of the proletarian literature in vogue at the time, he summarized the incident in a novel called ''Student Group'' and read it to Ueda. The Tsushima family was wary of Dazai's leftist activities. On January 16 of the following year, the Special High Police arrested Ueda and nine other students of the Hiroko Institute of Social Studies, who were working as activists for Seigen Tanaka's Communist Party. In college, Dazai met activist Eizo Kudo, and made a monthly financial contribution of ten yen to theJapanese Communist Party

The is a communist party in Japan. Founded in 1922, it is the oldest political party in the country. It has 250,000 members as of January 2024, making it one of the largest non-governing communist parties in the world. The party is chaired ...

. He was expelled from his family after his marriage to Hatsuyo Oyama in order to prevent any association of his illegal activities with his brother Bunji, who was a politician. After his marriage, Dazai was ordered to hide his sympathies and moved repeatedly. In July 1932, Bunji tracked him down, and had him turn himself in at the Aomori Police Station. In December, Dazai signed and sealed a pledge at the Aomori Prosecutor's Office to completely withdraw from leftist activities.

Early literary career

Dazai kept his promise and settled down. He managed to obtain the assistance of

Dazai kept his promise and settled down. He managed to obtain the assistance of Masuji Ibuse

was a Japanese author. His novel ''Black Rain (novel), Black Rain,'' about the Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, bombing of Hiroshima, was awarded the Noma Prize and the Order of Culture, Order of Cultural Merit.

Early life and educat ...

, an established writer whose connections helped him get his works published and establish his reputation. The next few years were productive for Dazai. He wrote at a feverish pace and used the pen name "Osamu Dazai" for the first time in a short story called "Ressha" ("列車", "Train"), published in 1933. This story was his first experiment with the I-novel

The I-novel (, , ) is a literary genre in Japanese literature used to describe a type of Confessional writing, confessional literature where the events in the story correspond to events in the author's life. This genre was founded based on the Jap ...

form that later became his trademark.

In 1935 it started to become clear to Dazai that he would not graduate. He also failed to obtain a job at a Tokyo newspaper. He finished '' The Final Years'' (''Bannen''), which was intended to be his farewell to the world, and tried to hang himself on March 19, 1935, failing yet again. Less than three weeks later, he developed acute appendicitis and was hospitalized. In the hospital, he became addicted to Pavinal, a morphine-based painkiller. After fighting the addiction for a year, in October 1936 he was taken to a mental institution, locked in a room and forced to quit cold turkey

"Cold Turkey" is a song written by John Lennon, released as a single in 1969 by the Plastic Ono Band on Apple Records, catalogue Apples 1001 in the United Kingdom, Apple 1813 in the United States. It is the second solo single issued by Lennon ...

.

The treatment lasted over a month.

During this time Dazai's wife Hatsuyo committed adultery with his best friend Zenshirō Kodate. This eventually came to light, and Dazai attempted to commit ''shinjū

is a Japanese term meaning "double suicide", used in common parlance to refer to any group suicide of two or more individuals bound by love, typically lovers, parents and children, and even whole families. A double suicide without consent is cal ...

'' (joint suicide) with his wife. They both took sleeping pills, but neither died. Soon after, Dazai divorced Hatsuyo. He quickly remarried, this time to a middle school teacher named Michiko Ishihara ( 石原美知子). Their first daughter, Sonoko ( 園子), was born in June 1941.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Dazai wrote a number of novels and short stories that are autobiographical in nature. His first story, ''Gyofukuki'' (魚服記, "Transformation", 1933), is a grim fantasy involving suicide. Other stories written during this period include ''Dōke no hana'' (道化の花, "Flowers of Buffoonery", 1935), ''Gyakkō'' (逆行, "Losing Ground", 1935), ''Kyōgen no kami'' (狂言の神, "The God of Farce", 1936), an epistolary novel called ''Kyokō no Haru'' (虚構の春, ''False Spring'', 1936) and the stories in the collection ''Bannen'' (1936; ''Declining Years'' or ''The Final Years''), which describe his sense of personal isolation and his debauchery.

Wartime years

Japan widened thePacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

by attacking the United States in December 1941, but Dazai was excused from the draft because of his chronic chest problems, as he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The censors became more reluctant to accept his work, but he managed to publish anyway. A number of the stories that he published during the war are retellings of stories by Ihara Saikaku

was a Japanese poet and creator of the " floating world" genre of Japanese prose (''ukiyo-zōshi'').

His born name may have been Hirayama Tōgo (平山藤五), the son of a wealthy merchant in Osaka, and he first studied haikai poetry under a ...

(1642–1693). Dazai's wartime works include ''Udaijin Sanetomo'' (右大臣実朝, "Minister of the Right Sanetomo", 1943), ''Tsugaru'' (1944), ''Pandora no Hako'' (パンドラの匣, ''Pandora's Box'', 1945–46), and ''Otogizōshi'' (お伽草紙, ''Fairy Tales'', 1945) in which he retells a number of Japanese fairy tales.

Dazai's house was burned down twice in the American bombing of Tokyo, but his family escaped unscathed and gained a son, Masaki (正樹), who was born in 1944. His third child, his daughter Satoko (里子), who later became a writer under the pseudonym Yūko Tsushima

Satoko Tsushima (30 March 1947 – 18 February 2016), known by her pen name Yūko Tsushima (津島 佑子 ''Tsushima Yūko''), was a Japanese fiction writer, essayist and critic. Tsushima won many of Japan's top literary prizes in her career, i ...

, was born in May 1947.

Postwar career

In the immediate postwar period, Dazai reached the height of his popularity. He depicted a dissolute life in postwar Tokyo in ''Viyon no Tsuma'' (ヴィヨンの妻, "Villon's Wife", 1947), depicting the wife of a poet who had abandoned her and her continuing will to live through hardships.

In 1946, Dazai published a controversial memoir, "Kuno no Nenkan" (Almanac of Pain), in which he describes the immediate aftermath of Japan's defeat and seeks to encapsulate how the Japanese felt at the time. Dazai reaffirmed his loyalty to the Japanese Emperor,

In the immediate postwar period, Dazai reached the height of his popularity. He depicted a dissolute life in postwar Tokyo in ''Viyon no Tsuma'' (ヴィヨンの妻, "Villon's Wife", 1947), depicting the wife of a poet who had abandoned her and her continuing will to live through hardships.

In 1946, Dazai published a controversial memoir, "Kuno no Nenkan" (Almanac of Pain), in which he describes the immediate aftermath of Japan's defeat and seeks to encapsulate how the Japanese felt at the time. Dazai reaffirmed his loyalty to the Japanese Emperor, Emperor Hirohito

, Posthumous name, posthumously honored as , was the 124th emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, from 25 December 1926 until Death and state funeral of Hirohito, his death in 1989. He remains Japan's longest-reigni ...

and his son Akihito

Akihito (born 23 December 1933) is a member of the Imperial House of Japan who reigned as the 125th emperor of Japan from 1989 until 2019 Japanese imperial transition, his abdication in 2019. The era of his rule was named the Heisei era, Hei ...

. However, Dazai also expressed his Communist beliefs in this memoir. Dazai also wrote ''Jugonenkan'' (''For Fifteen Years''), another autobiographical piece.

On December 14, 1946, a group of writers that included Dazai was joined by Yukio Mishima

Kimitake Hiraoka ( , ''Hiraoka Kimitake''; 14 January 192525 November 1970), known by his pen name Yukio Mishima ( , ''Mishima Yukio''), was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model, Shintoist, Ultranationalism (Japan), ultranationalis ...

for dinner at a restaurant. The latter recalled that on that occasion, he gave vent to his dislike of Dazai. According to a later statement by Mishima:

The disgust in which I hold Dazai's literature is in some way ferocious. First, I dislike his face. Second, I dislike his rustic preference for urban sophistication. Third, I dislike the fact that he played roles that were not appropriate for him.Other participants at the dinner could not remember if events occurred as Mishima described. They did report that he did not enjoy Dazai's "clowning" and that he and Dazai had a dispute about

Ōgai Mori Ogai or Ōgai is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Dmitry Ogai (born 1960), Kazakhstani football manager

*Mori Ōgai

Lieutenant-General , known by his pen name , was a Japanese people, Japanese Military medicine, Army Surgeo ...

, a writer whom Mishima admired.

In July 1947, Dazai's novel ''Shayo'' (''

In July 1947, Dazai's novel ''Shayo'' (''The Setting Sun

is a Japanese novel by Osamu Dazai first published in 1947. The story centers on an aristocratic family in decline and crisis during the early years after World War II.

Plot summary

Twenty-nine-year-old Kazuko, her brother Naoji, and their w ...

'', translated 1956) was published. It depicts the decline of the Japanese nobility

The was the hereditary peerage of the Empire of Japan, which existed between 1869 and 1947. It was formed by merging the feudal lords (''daimyō'') and court nobles (''kuge'') into one system modelled after the British peerage. Distinguished ...

after the war. It was partly based on the diary of Shizuko Ōta ( 太田静子), an admirer of Dazai's work who first met him in 1941. The pair had a daughter, Haruko, ( 治子) in 1947.

A heavy drinker, Dazai became an alcoholic and his health deteriorated rapidly. At this time he met Tomie Yamazaki ( 山崎富栄), a beautician whose husband had been killed in the war after just ten days of marriage. Dazai abandoned his wife and children and moved in with Tomie.

Dazai began writing his novel '' No Longer Human'' (人間失格 ''Ningen Shikkaku'', 1948) at the hot-spring resort in Atami

is a city located in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 36,865 in 21,593 households

. He then moved to Ōmiya with Tomie and stayed there until mid-May 1948, finishing his novel. A quasi-autobiography, it depicts a self-destructive young man who believes that he is disqualified from being human. The book has been translated into several foreign languages.

In the spring of 1948, Dazai worked on ''Goodbye'', a novella scheduled to be serialized in the ''Asahi Shimbun

is a Japanese daily newspaper founded in 1879. It is one of the oldest newspapers in Japan and Asia, and is considered a newspaper of record for Japan.

The ''Asahi Shimbun'' is one of the five largest newspapers in Japan along with the ''Yom ...

''. It was never finished.

Death

On June 13, 1948, Dazai and Tomie drowned themselves in the rain-swollen Tamagawa Canal, near his house. Their bodies were not discovered until six days later, on June 19, which would have been his 39th birthday. His grave is at the temple of Zenrin-ji, in

On June 13, 1948, Dazai and Tomie drowned themselves in the rain-swollen Tamagawa Canal, near his house. Their bodies were not discovered until six days later, on June 19, which would have been his 39th birthday. His grave is at the temple of Zenrin-ji, in Mitaka, Tokyo

file:井之頭恩賜公園 (16016034730).jpg, 260px, Inokashira Park in Mitaka

is a Cities of Japan, city in the Western Tokyo region of Tokyo Metropolis, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 190,403, and a population density of 12,00 ...

.

At the time, there was a lot of speculation about the incident. Keikichi Nakahata, a kimono merchant who frequented the young Tsushima family, was shown the scene of the suicide by a detective from Mitaka police station. He speculated that "Dazai was asked to die, and he simply agreed, but just before his death, he suddenly felt an obsession with life."

Works

See also

* Dazai Osamu Prize *List of Japanese writers

This is an alphabetical list of writers who are Japanese, or are famous for having written in the Japanese language.

Writers are listed by the native order of Japanese names—family name followed by given name—to ensure consistency, although ...

*Osamu Dazai Memorial Museum

The , also commonly referred to as (), is a writer's home museum located in the Kanagi, Aomori, Kanagi area of Goshogawara, Aomori, Goshogawara in Aomori Prefecture, Japan. It is dedicated to the late author Osamu Dazai, who spent some of his ear ...

References

Sources

* O'Brien, James A., ed. ''Akutagawa and Dazai: Instances of Literary Adaptation''. Cornell University Press, 1983. * * Ueda, Makoto. ''Modern Japanese Writers and the Nature of Literature''. Stanford University Press, 1976. * * "Nation and Region in the Work of Dazai Osamu," inRoy Starrs

Roy Starrs (born 1946) is a British-Canadian scholar of Japanese literature and culture who teaches at the University of Otago in New Zealand. He has written critical studies of the major Japanese writers Yasunari Kawabata, Naoya Shiga, Osamu Daza ...

External links

Osamu Dazai's works in Japanese

on

Aozora bunko

Aozora Bunko (, , also known as the "Open Air Library") is a Japanese digital library. This online collection encompasses several thousand works of Japanese-language fiction and non-fiction. These include out-of-copyright books or works that t ...

*Osamu Dazai's grave

at JLPP (Japanese Literature Publishing Project) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Dazai, Osamu 1909 births 1948 suicides 1948 deaths 20th-century Japanese novelists Japanese male short story writers People from the Empire of Japan Writers from Aomori Prefecture University of Tokyo alumni Suicides by drowning in Japan 20th-century Japanese short story writers 20th-century Japanese male writers Joint suicides Aomori High School alumni