David Edward Jackson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

David Edward Jackson (c. 1788 – December 24, 1837) was an

Bodmer (1840–1843) It is not known if Jackson returned to St. Louis with Ashley that fall, or traveled with Jedediah Smith in the spring of 1823. At that time, Major Henry ordered Smith and some other men to go down the Missouri to Grand River in order to meet Ashley and buy horses from the

By early 1831, Jackson was in southeast Missouri's lead belt, attending to his personal affairs and those of his brother George, who died on March 26, 1831. On April 7, he returned to St. Louis to meet with his partners for a trade trip to Santa Fe, which was controlled by the Spanish.Hays, p. 86 The caravan of wagons left St. Louis on April 10, 1831, traveling down the

By early 1831, Jackson was in southeast Missouri's lead belt, attending to his personal affairs and those of his brother George, who died on March 26, 1831. On April 7, he returned to St. Louis to meet with his partners for a trade trip to Santa Fe, which was controlled by the Spanish.Hays, p. 86 The caravan of wagons left St. Louis on April 10, 1831, traveling down the

''History of Oregon''

San Francisco: History Co., 1890 Doctor Ira L. Babcock was selected as supreme judge with probate powers to deal with Young's estate. The activities that followed Young's death contributed to the creation of a

American pioneer

American pioneers, also known as American settlers, were European American,Asian American, and African American settlers who migrated westward from the British Thirteen Colonies and later the United States of America to settle and develop areas ...

, trapper, fur trader, and explorer.

Davey Jackson has often been referenced to as a son of the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

. His father Edward Jackson and his Uncle George Jackson both served as Virginian Militia Officers during the Revolutionary War. During the War of 1812, Jackson was commissioned as an Ensign in the 19th Infantry in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

.

The Jackson family included several notable military patriots. Genealogical records show that Colonel Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, who famously led the Confederate victory at Harper’s Ferry, Maryland, in 1862, was the nephew of David Edward Jackson, founder of Jackson Hole. Despite their shared last name, however, they were not related to President Andrew Jackson, whose family came from South Carolina and had Scots-Irish roots.

Davey Jackson was born in Buckhannon, Virginia (present day West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

), on October 30, 1788, into a prominent family. In addition to learning the business, farming, hunting and surveying skills of his father, he was educated at the Virginia Randolph Academy. In 1809, at age 21, he married Juliet Norris and the couple had four children.

In 1822, Jackson saw an ad in a Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

newspaper, seeking young men to travel the Missouri River

The Missouri River is a river in the Central United States, Central and Mountain states, Mountain West regions of the United States. The nation's longest, it rises in the eastern Centennial Mountains of the Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Moun ...

to the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

, to be employed as guides, hunters, explorers and trappers with the Rocky Mountain Trading Company. Although his wife was against the idea, Jackson saw this as a great opportunity to explore and gain wealth. He joined the company, along with many other young men, such as Jim Bridger

James Felix Bridger (March 17, 1804 – July 17, 1881) was an American mountain man, Animal trapping, trapper, Army scout, and wilderness guide who explored and trapped in the Western United States in the first half of the 19th century. He was ...

, William Sublette, and Jedediah Smith

Jedediah Strong Smith (January 6, 1799 – May 27, 1831) was an American clerk, transcontinental pioneer, frontiersman, hunter, trapper, author, cartography, cartographer, mountain man and explorer of the Rocky Mountains, the Western Unit ...

, while his wife and children remained in Virginia.

For eight years Jackson pursued this adventure, fraught with troubles, including harsh weather, difficult terrain, competition from Canadian, British and French trading companies, and both kindness and treachery from the Native tribes. The company suffered many losses as their beaver pelts were often stolen. Many trappers died under the harsh conditions of life in the Rocky Mountains, or by murder at the hands of competitors or native tribes.

Eventually Davey Jackson, William Sublette and Jedediah Smith formed their own fur trading company, “Smith, Jackson and Sublette.” Jackson often returned to the valley in the Teton Mountains where he had established his own trapping territory, which Sublette eventually dubbed “Jackson’s Hole.” (Today, the town of Jackson, Wyoming

Jackson is a resort town in Teton County, Wyoming, United States. The population was 10,760 at the 2020 census, up from 9,577 in 2010. It is Teton County's only incorporated municipality and county seat, and it is the largest incorporated town ...

, in that valley, bears his name.)

He and his partners sold out in 1830, as the fur trade was declining. Jackson became involved in other expeditions, including to Santa Fe (in present-day New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

) and California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, both under Mexican control since it had achieved independence from Spain in 1821.

Jackson returned east, without amassing his fortune. He reunited with his son William Pitt Jackson in St. Genevieve, Missouri, in the early 1830’s.

On a business trip to Paris, Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

in 1837, Jackson became ill with Typhus Fever

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure ...

. By December 1837, although gravely ill, he managed to write a letter to his oldest son Edward John Jackson, known as “Ned,” asking him to conclude all his business dealings. He provided his son a thorough written account of all the money that was owed to him, and all the debts he had yet to pay.

Jackson died shortly after that at age 49, on December 24, 1837, in Paris, Tennessee

Paris is a city in and the county seat of Henry County, Tennessee, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 10,316.

A replica of the Eiffel Tower stands in the southern part of Paris.

History

The present site of Par ...

. He was a long time member of the Masons. Upon his death Jackson was buried by fellow Masons from Paris, Tennessee, in the Paris City Cemetery, Henry County, Tennessee

Henry County is a county located on the northwestern border of the U.S. state of Tennessee, and is considered part of West Tennessee. As of the 2020 census, the population was 32,199. Its county seat is Paris. The county is named for the Virgin ...

.

Early life

Paternal ancestry

David Edward Jackson was the grandson of John Jackson (1715 or 1719 – 1801) and Elizabeth Cummins (also known as Elizabeth Comings and Elizabeth Needles) (1723–1828). John Jackson was a Protestant (Ulster-Scottish) fromColeraine

Coleraine ( ; from , 'nook of the ferns'Flanaghan, Deirdre & Laurence; ''Irish Place Names'', page 194. Gill & Macmillan, 2002. ) is a town and Civil parishes in Ireland, civil parish near the mouth of the River Bann in County Londonderry, No ...

, County Londonderry

County Londonderry (Ulster Scots dialects, Ulster-Scots: ''Coontie Lunnonderrie''), also known as County Derry (), is one of the six Counties of Northern Ireland, counties of Northern Ireland, one of the thirty-two Counties of Ireland, count ...

, Ireland. While living in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, England, he was convicted of the capital crime of larceny for stealing £170; the judge at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

sentenced him to seven years of indentured servitude in the British colonies of North America. Elizabeth, a strong, blonde woman over tall, born in London, was also convicted of larceny in an unrelated case for stealing 19 pieces of silver, jewelry, and fine lace, and received a similar sentence. They both were transported on the prison ship ''Litchfield'', which departed London in May 1749 with 150 convicts. John and Elizabeth met on board and had declared their love in the weeks before the ship arrived at Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

. Although they were sent to different locations in Maryland for their indentures, the couple married in July 1755.

The family migrated west across the Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a Physiographic regions of the United States, physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Highlands range. The mountain range is located in the Eastern United States and extends 550 miles southwest from southern ...

to settle near Moorefield, Virginia (now West Virginia) in 1758. In 1770, they moved farther west to the Tygart Valley

The Tygart Valley River — also known as the Tygart River — is a principal tributary of the Monongahela River, approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed ...

. They began to acquire large parcels of virgin farming land near the present-day town of Buckhannon, including 3,000 acres (12 km²) in Elizabeth's name. John and his two teenage sons were early recruits for the American Revolutionary War, fighting in the Battle of Kings Mountain

The Battle of Kings Mountain was a military engagement between Patriot and Loyalist militias in South Carolina during the southern campaign of the American Revolutionary War, resulting in a decisive victory for the Patriots. The battle took pl ...

on October 7, 1780. John finished the war as captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

and served as a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

of the Virginia militia after 1787. While the men were in the Army, Elizabeth converted their home to a haven, "Jackson's Fort," for refugees from Indian attacks.

John and Elizabeth had eight children. Their second son was Edward Jackson (March 1, 1759 – December 25, 1828); Edward and his wife had three boys and three girls; the second boy being David. Their third son was Jonathan Jackson, father of Thomas, known as Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general and military officer who served during the American Civil War. He played a prominent role in nearly all military engagements in the eastern the ...

when he served as a general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

in the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

.

Childhood

David Edward Jackson, son of Col. Edward Jackson, was born in Randolph County in theAllegheny Mountains

The Allegheny Mountain Range ( ) — also spelled Alleghany or Allegany, less formally the Alleghenies — is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the Eastern United States and Canada. Historically it represented a significant barr ...

of what was then part of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

and is now in West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

. When he was eight, his mother died. His father remarried three years later. In 1801, when he was 13, his family moved west, settling near Weston, West Virginia

Weston is a city in and the county seat of Lewis County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 3,943 at the 2020 census. It is home to the Museum of American Glass in West Virginia and the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum.

History

W ...

Lewis County, on the Allegheny Plateau

The Allegheny Plateau ( ) is a large dissected plateau area of the Appalachian Mountains in western and central New York, northern and western Pennsylvania, northern and western West Virginia, and eastern Ohio. It is divided into the unglacia ...

. Jackson's father and stepmother had nine more children.

Ashley and Henry

left, 240px, Regions of the Missouri River Watershed Jackson married and moved to Ste. Genevieve, Missouri, with his wife and four children in the early 1820s, planning to engage in farming. The town had been founded by French colonists in the late 18th century. His older brother, George, had preceded him to the area and owned a sawmill. Instead of farming, Jackson responded to William Ashley's advertisement looking to employ men for his and Andrew Henry's newfur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal ecosystem, boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals h ...

venture. Jackson was probably hired as a clerk.Hays, p. 76 In the spring of 1822, Jackson headed up the Missouri River with Henry and 150 other men in a fur trade expedition to Native American tribes on the upper river. A few weeks later, Ashley sent more men, including Jedediah Smith on a boat called the ''Enterprize''. It sank and left the men stranded in the wilderness for several weeks.

Ashley himself brought up an additional 46 men on a replacement boat, and they and the stranded group finally reached Fort Henry. It had been built over the summer by the first group of 150 men.

thumb , 180px , right , Arikara warriorBodmer (1840–1843) It is not known if Jackson returned to St. Louis with Ashley that fall, or traveled with Jedediah Smith in the spring of 1823. At that time, Major Henry ordered Smith and some other men to go down the Missouri to Grand River in order to meet Ashley and buy horses from the

Arikara

The Arikara ( ), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011) ...

, but warning him of the Native Americans' hostility to whites. They had recently had a skirmish with men from the ''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011) ...

Missouri Fur Company

The Missouri Fur Company (also known as the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company or the Manuel Lisa Trading Company) was one of the earliest fur trading companies in St. Louis, Missouri. Dissolved and reorganized several times, it operated under variou ...

. Ashley, who was bringing supplies as well as 70 new men up the river by boat, met Smith at the Arikara

The Arikara ( ), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011) ...

village on May 30. They negotiated a trade for several horses and 200 buffalo robes. They planned to leave as soon as possible to avert trouble, but weather delayed them. An incident precipitated an Arikara attack on the Ashley party. Forty Ashley men were caught in a vulnerable position, and 12 were killed.

Ashley and the rest of the surviving party traveled by boat downriver, ultimately enlisting aid from Colonel ''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011) ...

Henry Leavenworth

Henry Leavenworth (December 10, 1783 – July 21, 1834) was an American soldier active in the War of 1812 and early military expeditions against the Plains Indians. He established Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. The city of Leavenworth, Kansas; Lea ...

, Commander of Fort Atkinson. In August, Leavenworth sent a force of 250 military men, 80 Ashley-Henry men, 60 men of the Missouri Fur Company

The Missouri Fur Company (also known as the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company or the Manuel Lisa Trading Company) was one of the earliest fur trading companies in St. Louis, Missouri. Dissolved and reorganized several times, it operated under variou ...

, and a number of Lakota Sioux

The Lakota (; or ) are a Native American people. Also known as the Teton Sioux (from ), they are one of the three prominent subcultures of the Sioux people, with the Eastern Dakota (Santee) and Western Dakota (). Their current lands are in N ...

warriors, enemies of the Arikara. They intended to subdue and punish the Arikara. After a botched campaign, Leavenworth negotiated a peace treaty.

Either David Jackson or his brother George had been appointed commander of one of the two squads of the Ashley-Henry men in this military expedition.Hays, p. 77

Smith, Jackson & Sublette

Little is known about Jackson's movements until just after the 1826 Rocky Mountain Rendezvous, a major gathering of trappers and traders. It is presumed he was at the first, 1825 rendezvous held on Henrys Fork of the Green River, but he may not have been at the one held in 1826 at Bear River inCache Valley

Cache Valley ''( Shoshoni: Seuhubeogoi, “Willow Valley”)'' is a valley of northern Utah and southeast Idaho, United States, that includes the Logan metropolitan area. The valley was used by 19th century mountain men and was the site of th ...

. Soon after the rendezvous, Ashley, along with his party taking back the furs, traveled with Smith and William Sublette to near present-day Georgetown, Idaho. There, Jackson and the other men bought out Ashley's share of the Ashley-Smith partnership.

As a partner, Jackson took on the role of field manager, possibly because of his similar role when working for Ashley. That fall, Jackson, Sublette, and Robert Campbell trapped along the Snake River

The Snake River is a major river in the interior Pacific Northwest region of the United States. About long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, which is the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. Begin ...

system, then moved up into the upper Missouri and over the Great Divide to the headwaters of the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

.)

Jackson and his party traveled south to Cache Valley

Cache Valley ''( Shoshoni: Seuhubeogoi, “Willow Valley”)'' is a valley of northern Utah and southeast Idaho, United States, that includes the Logan metropolitan area. The valley was used by 19th century mountain men and was the site of th ...

, where they spent the rest of the 1826-1827 winter. He was at the 1827 rendezvous at Bear Lake, then returned to St. Louis, Missouri, which had become a center of fur trade, with Sublette for a short time.Hays, p. 80

Jackson returned to the fur country for the 1828 rendezvous, after which he traveled with a party to the Flathead Lake

Flathead Lake (, ) is a large natural lake in northwest Montana, United States.

The lake is a remnant of the ancient, massive glacial dammed lake, Glacial Lake Missoula, Lake Missoula, of the era of the last interglacial. Flathead Lake is a nat ...

, Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

region, where they wintered. The next spring, Smith found him along the Flathead River. The two partners and their men trapped down to Pierre's Hole, where they joined Sublette. The rendezvous that year (1829), was held near present-day Lander, Wyoming

Lander is a city and the county seat of Fremont County, Wyoming. It is located in central Wyoming, along the Middle Fork Popo Agie River, Middle Fork of the Popo Agie River, just south of the Wind River Indian Reservation. It is a tourism center ...

. Jackson is thought to have returned afterward to the upper Snake River

The Snake River is a major river in the interior Pacific Northwest region of the United States. About long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, which is the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. Begin ...

region in northwest Wyoming, then traveled east to spend the winter with Smith and Sublette along the Wind

Wind is the natural movement of atmosphere of Earth, air or other gases relative to a planetary surface, planet's surface. Winds occur on a range of scales, from thunderstorm flows lasting tens of minutes, to local breezes generated by heatin ...

and Powder

A powder is a dry solid composed of many very fine particles that may flow freely when shaken or tilted. Powders are a special sub-class of granular materials, although the terms ''powder'' and ''granular'' are sometimes used to distinguish se ...

rivers. Jackson returned to the upper Snake in the spring of 1830, then returned to the Wind River Valley for the annual rendezvous.

At the rendezvous, Smith, Jackson and Sublette sold out their interests in the fur trade to a group of men who called the firm the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. The three partners returned to St. Louis, having made a tidy profit in their enterprise.

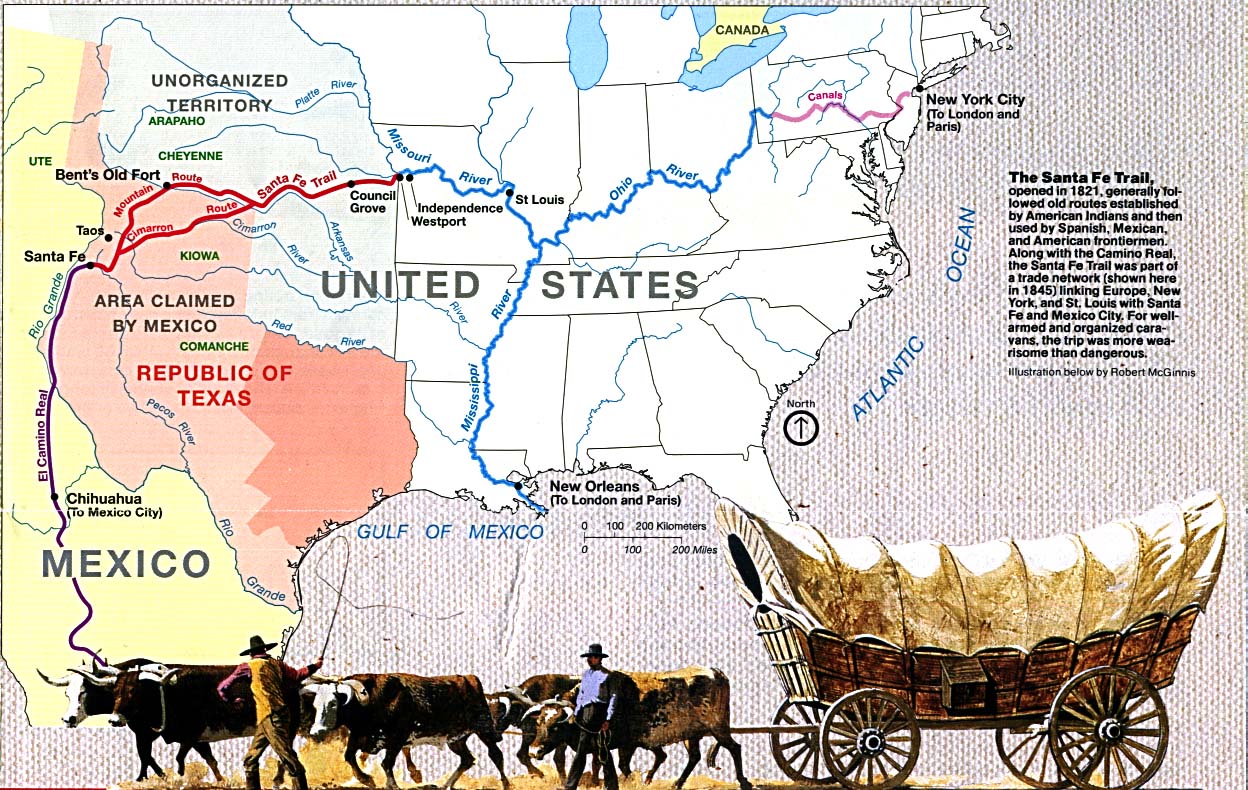

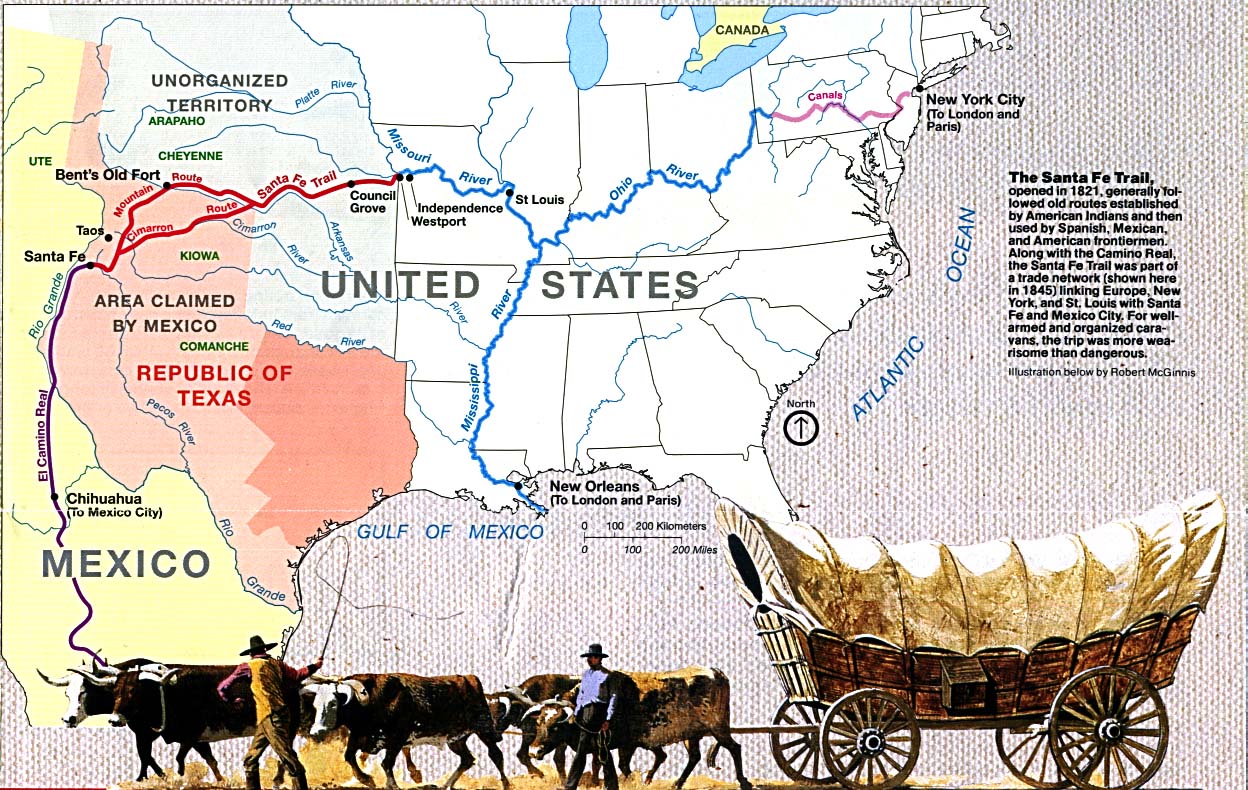

Trip to Santa Fe

By early 1831, Jackson was in southeast Missouri's lead belt, attending to his personal affairs and those of his brother George, who died on March 26, 1831. On April 7, he returned to St. Louis to meet with his partners for a trade trip to Santa Fe, which was controlled by the Spanish.Hays, p. 86 The caravan of wagons left St. Louis on April 10, 1831, traveling down the

By early 1831, Jackson was in southeast Missouri's lead belt, attending to his personal affairs and those of his brother George, who died on March 26, 1831. On April 7, he returned to St. Louis to meet with his partners for a trade trip to Santa Fe, which was controlled by the Spanish.Hays, p. 86 The caravan of wagons left St. Louis on April 10, 1831, traveling down the Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail was a 19th-century route through central North America that connected Franklin, Missouri, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. Pioneered in 1821 by William Becknell, who departed from the Boonslick region along the Missouri River, the ...

. To save time, the group decided to take the "Cimarron cutoff," at the risk of not finding water for two days. Smith went missing while looking for water, but the caravan continued on, hoping he would find them.

Upon reaching Santa Fe on July 4, 1831, the members of the trading party discovered a Mexican merchant at the Santa Fe market offering several of Smith's personal belongings for sale. When questioned about the items, the merchant indicated that he had acquired them from a band of Comanche

The Comanche (), or Nʉmʉnʉʉ (, 'the people'), are a Tribe (Native American), Native American tribe from the Great Plains, Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the List of federally recognized tri ...

hunters. Smith had encountered and been killed by a group of Comanche. His death resulted in Jackson and Sublette reorganizing their partnership.

California

While in Santa Fe, Jackson partnered with David Waldo, to journey to California to sell the merchandise he had transported from Missouri. Waldo convinced him of the viability of traveling to California to purchasemule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey, and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two ...

s, and to drive them back to Missouri to sell, to yield more profit. Jackson and Sublette traveled to Taos

Taos or TAOS may refer to:

Places

* Taos County, New Mexico, United States

** Taos, New Mexico, a city, the county seat of Taos County, New Mexico

*** Taos art colony, an art colony founded in Taos, New Mexico

** Taos Pueblo, a Native American ...

where Jackson met Ewing Young, who had traveled between Santa Fe and California the previous year. He persuaded Jackson that his knowledge of the area would be indispensable to Jackson and Waldo in the mule venture. It was decided Jackson would take a group of men directly to California, and travel through the area buying mules. Young and his group of men would trap along the way to California, and meet up with Jackson in time to drive the mules back to Santa Fe. Jackson left for Santa Fe on August 25, 1831.Hays, p. 90

On September 6, Jackson's group left Santa Fe. Members of the group included, Jackson and his slave, Jim; Jedediah Smith's younger brother Peter, Jonathan Trumbull Warner, Samuel Parkman, and possibly David's brother William Waldo; Moses Carson, brother of Kit; and four other men. Several weeks later, they reached Tucson, Arizona

Tucson (; ; ) is a city in Pima County, Arizona, United States, and its county seat. It is the second-most populous city in Arizona, behind Phoenix, Arizona, Phoenix, with a population of 542,630 in the 2020 United States census. The Tucson ...

, and went on to the Gila River

The Gila River (; O'odham ima Keli Akimel or simply Akimel, Quechan: Haa Siʼil, Maricopa language: Xiil) is a tributary of the Colorado River flowing through New Mexico and Arizona in the United States. The river drains an arid watershed of ...

, which they followed to the Colorado River

The Colorado River () is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and in northern Mexico. The river, the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), 5th longest in the United St ...

. They crossed the Colorado River and the Colorado Desert

The Colorado Desert is a part of the larger Sonoran Desert located in California, United States, and Baja California, Mexico. It encompasses approximately , including the heavily irrigated Coachella, Imperial and Mexicali valleys. It is home to ...

, reaching San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

in early November.

Jackson traveled up the California coast as far north as the lower end of the San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

. By the end of March, 1832, when he met with Young in Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

, he had purchased only 600 mules and 100 horses rather than the more than 1,000 they had planned. In May, the two groups drove the animals to the Colorado River, reaching it at its floodstage in June. After 12 days, they had the animals swim across. Jackson's and Young's parties again split; Young to take $10,000 of Jackson/Waldo cash and property and return to California and continue trapping and buying mules to drive back later. Jackson took possession of the skins which Young had trapped to that point.

Due to the summer heat, many of the mules died on the way back to Santa Fe, which the party reached in the first week of July. Jackson sold part of the herd of animals in Santa Fe. Ira Smith, another Jedediah Smith brother, had traveled to Santa Fe to meet Peter. Ira and Jackson headed back to St. Louis with the remaining animals.

Later years and death

Upon his return to Missouri, the 44-year-old Jackson began to have health problems. He spent his remaining years trying to put his financial affairs in order. He had never heard from Ewing Young, after leaving him with the substantial amount of cash and property at the Colorado River, but was never healthy enough to return to California to try to collect payment. In January 1837, he finally was able to travel toParis, Tennessee

Paris is a city in and the county seat of Henry County, Tennessee, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 10,316.

A replica of the Eiffel Tower stands in the southern part of Paris.

History

The present site of Par ...

, to try to collect money on some investments he had made there. While there, Jackson contracted typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

. He lingered for several months and died on December 24, 1837.

Young's later years

Ewing Young left California for Oregon in 1834. With the money and property secured from Jackson, he had capital for several ventures.Hays, p. 103 In February 1841, Young died without any known heir and without a will. Probate court had to deal with his estate, which had many debtors and creditors among the settlers. Bancroft, Hubert and Frances Fuller Victor''History of Oregon''

San Francisco: History Co., 1890 Doctor Ira L. Babcock was selected as supreme judge with probate powers to deal with Young's estate. The activities that followed Young's death contributed to the creation of a

provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

in the Oregon Country.

Jackson's legacy

* Jackson Lake, andJackson Hole

Jackson Hole (originally called Jackson's Hole by mountain men) is a valley between the Gros Ventre Range, Gros Ventre and Teton Range, Teton mountain ranges in the U.S. state of Wyoming, near the border with Idaho, in Teton County, Wyoming, T ...

, a valley in Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

are named for David Jackson. The town of Jackson, Wyoming

Jackson is a resort town in Teton County, Wyoming, United States. The population was 10,760 at the 2020 census, up from 9,577 in 2010. It is Teton County's only incorporated municipality and county seat, and it is the largest incorporated town ...

, in turn, derives its name from the valley.

*The Hoback Basin, a braided floodplain of the Hoback River

The Hoback River, once called the Fall River, is an approximately -long tributary of the Snake River in the U.S. state of Wyoming. It heads in the northern Wyoming Range of Wyoming and flows northeast, northwest, and then west through the Bridg ...

where Bondurant, Wyoming is located, was once known as Jackson's Little Hole.

Notes

Citations

References

* *originally published in * * * *Jackson, John C., ''Shadow on the Tetons: David E. Jackson and the Claiming of the American West,'' Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Co., 1993. {{DEFAULTSORT:Jackson, David Edward 1780s births 1837 deaths Santa Fe Trail American fur traders Deaths from typhoid fever in the United States