David E. Lilienthal on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

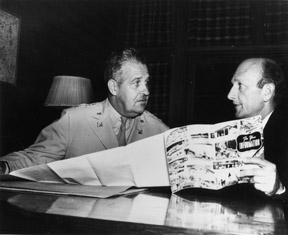

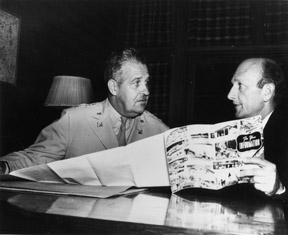

David Eli Lilienthal (July 8, 1899 – January 15, 1981) was an American attorney and public administrator, best known for his presidential appointment to head

Lilienthal was one of the first directors of the

Lilienthal was one of the first directors of the

Subsequently, the United States established the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to provide civilian control of this resource. Lilienthal was appointed as chair of the AEC on October 28, 1946, and served until February 15, 1950, one of the pioneers of civilian control of the American atomic energy program. He intended to administer a program that would "harness the atom" for peaceful purposes, principally atomic power. Lilienthal gave high priority to peaceful uses, especially nuclear power plants. However coal was cheap and the power industry was not interested. The first plant was begun under Eisenhower in 1954.

As chairman of the AEC in the late 1940s, during the early years of the

Subsequently, the United States established the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to provide civilian control of this resource. Lilienthal was appointed as chair of the AEC on October 28, 1946, and served until February 15, 1950, one of the pioneers of civilian control of the American atomic energy program. He intended to administer a program that would "harness the atom" for peaceful purposes, principally atomic power. Lilienthal gave high priority to peaceful uses, especially nuclear power plants. However coal was cheap and the power industry was not interested. The first plant was begun under Eisenhower in 1954.

As chairman of the AEC in the late 1940s, during the early years of the

online

*Wang, Jessica. (1999). ''American Science in an Age of Anxiety''. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. .

David E. Lilienthal Papers at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton UniversityAnnotated bibliography for David Lilienthal from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Lilienthal, David E. 1899 births 1981 deaths Lawyers from Chicago People from Morton, Illinois People from Michigan City, Indiana DePauw University alumni Harvard Law School alumni Franklin D. Roosevelt administration personnel Chairpersons of the United States Atomic Energy Commission Tennessee Valley Authority people American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent American people of Slovak-Jewish descent The Century Foundation Members of the American Philosophical Society Delta Upsilon members

Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolin ...

and later the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He had practiced public utility law and led the Wisconsin Public Utilities Commission.

Later he was co-author with Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson ( ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American politician and lawyer. As the 51st United States Secretary of State, U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to ...

(later Secretary of State) of the 1946 '' Report on the International Control of Atomic Energy,'' which outlined possible methods for international control of nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s. As chair of the AEC, he was one of the pioneers in civilian management of nuclear power resources.

Early life

Born inMorton, Illinois

Morton is a village in Tazewell County, Illinois, United States. The population was 17,117 at the 2020 census. The community holds a yearly Morton Pumpkin Festival for four days every September, and claims that "99 percent of the world's canne ...

in 1899, David Lilienthal was the oldest son of Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

immigrants from Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

. His mother Minna Rosenak (1874–1956) came from Szomolány (now Smolenice) in Slovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

, emigrating to America at age 17. His father Leo Lilienthal (1868–1951) was from Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, serving several years in the Hungarian army before emigrating to the United States in 1893. Minna and Leo were married in Chicago in 1897, then moved to the town of Morton, where Leo briefly operated a dry goods store.

Leo's business ventures took the family several places. Young David was raised principally in the Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

towns of Valparaiso and Michigan City. Although he spent part of his sophomore

In the United States, a sophomore ( or ) is a person in the second year at an educational institution; usually at a secondary school or at the college and university level, but also in other forms of Post-secondary school, post-secondary educatio ...

year in Gary, he graduated in 1916 from Elston High School in Michigan City.

Education and marriage

Lilienthal attendedDePauw University

DePauw University ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Greencastle, Indiana, United States. It was founded in 1837 as Indiana Asbury College and changed its name to DePauw University in 1884. The college has a Methodist heritage and was ...

in Greencastle, Indiana

Greencastle is a city in Greencastle Township, Putnam County, Indiana, United States, and the county seat of Putnam County. It is located near Interstate 70 approximately halfway between Terre Haute and Indianapolis in the west-central portion ...

, where he graduated Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

in 1920. There he joined Delta Upsilon

Delta Upsilon (), commonly known as DU, is a collegiate men's fraternity founded on November 4, 1834, at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. It is the sixth-oldest, all-male, college Greek-letter organization founded in North America ...

social fraternity and was elected president of the student body. He was active in forensics

Forensic science combines principles of law and science to investigate criminal activity. Through crime scene investigations and laboratory analysis, forensic scientists are able to link suspects to evidence. An example is determining the time and ...

and won a state oratorical contest in 1918. He also gained distinction as a light heavyweight

Light heavyweight is a weight class in combat sports.

Boxing

Professional

In professional boxing, the division is above and up to , falling between super middleweight and cruiserweight (boxing), cruiserweight.

The light heavyweight class has ...

boxer.Current Biography, 1944, p. 413.

After a summer job in 1920 as a reporter for the Mattoon, Illinois

Mattoon ( ) is a city in Coles County, Illinois, United States. The population was 16,870 as of the 2020 census. The city is home to Lake Land College and has close ties with its neighbor, Charleston, Illinois, Charleston. Both are principal cit ...

, ''Daily Journal-Gazette'', Lilienthal entered Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, Harvard Law School is the oldest law school in continuous operation in the United ...

. Although his grades were average until his third and final year at Harvard, he acquired an important mentor in Professor Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, advocating judicial restraint.

Born in Vienna, Frankfurter im ...

, later an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is a justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1 ...

.

While at DePauw, Lilienthal met his future wife, Helen Marian Lamb (1896–1999), a fellow student. Born in Oklahoma, she had moved with her family to Crawfordsville, Indiana

Crawfordsville () is a city in Montgomery County, Indiana, Montgomery County in west central Indiana, United States, west by northwest of Indianapolis. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the city had a population of 16,306. The c ...

, in 1913. They were married in Crawfordsville in 1923, after Helen had completed her M.A. at Radcliffe while David was a law student at Harvard.

Law practice and public appointment

With a strong recommendation from Frankfurter, Lilienthal entered the practice of law inChicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

in 1923 with Donald Richberg. Prominent in labor law, Richberg gave Lilienthal a major role in writing his firm's brief for the appellant

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

s in ''Michaelson v. United States'', 266 U.S. 42 (1924), a landmark case in which the Supreme Court upheld the right of striking railroad workers to jury trials in cases in which they were charged with criminal contempt. Richberg also assigned Lilienthal to write major parts of what became the Railway Labor Act of 1926. In 1925, Lilienthal assisted criminal defense lawyers Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the 19th century for high-profile representations of trade union causes, and in the 20th century for several criminal matters, including the ...

and Arthur Garfield Hays in their successful defense of Dr. Ossian Sweet, an African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

physician tried in Detroit

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

for killing a white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

man who was part of a mob that attacked Sweet's home. Afterward, Lilienthal wrote about the case and issues of self-defense in an article published in ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

.''

Lilienthal left Richberg's firm in 1926 to concentrate on public utility

A public utility company (usually just utility) is an organization that maintains the infrastructure for a public service (often also providing a service using that infrastructure). Public utilities are subject to forms of public control and ...

law. He represented the city of Chicago in the case of ''Smith v. Illinois Bell Telephone Co.,'' 282 U.S. 133 (1930), in which a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court resulted in a refund of $20,000,000 to telephone customers who had been overcharged. From 1926 to 1931, Lilienthal also edited a legal information service on public utilities for Commerce Clearing House.

In 1931, Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

's reform-minded Republican governor, Philip La Follette

Philip Fox La Follette (May 8, 1897August 18, 1965) was an American politician who served during the 1930s as the 27th and 29th governor of Wisconsin. La Follette first served as a Republican from 1931 until 1933, where he lost renomination in ...

, asked him to become a member of the state's reorganized Railroad Commission, renamed that year as the Public Service Commission.

As the commission's leading member, Lilienthal expanded its staff and launched aggressive investigations of Wisconsin's gas, electric and telephone utilities. By September 1932, the commission achieved rate reductions totaling more than $3 million affecting over a half-million customers. But, its attempt to force a one-year 12.5 percent rate cut on the Wisconsin Telephone Company, a subsidiary

A subsidiary, subsidiary company, or daughter company is a company (law), company completely or partially owned or controlled by another company, called the parent company or holding company, which has legal and financial control over the subsidia ...

of AT&T

AT&T Inc., an abbreviation for its predecessor's former name, the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, is an American multinational telecommunications holding company headquartered at Whitacre Tower in Downtown Dallas, Texas. It is the w ...

, was quashed by the Wisconsin courts. After La Follette's defeat in the 1932 Republican primary election

Primary elections or primaries are elections held to determine which candidates will run in an upcoming general election. In a partisan primary, a political party selects a candidate. Depending on the state and/or party, there may be an "open pr ...

, Lilienthal began putting out feelers for a federal appointment in the newly elected Democratic administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

.

Lilienthal and the Tennessee Valley Authority

Lilienthal was one of the first directors of the

Lilienthal was one of the first directors of the Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolin ...

(TVA). He earned his credentials for the appointment working under labor lawyer Donald Richberg and as an appointed member of the Public Service Commission of Wisconsin under Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

's governor Philip La Follette

Philip Fox La Follette (May 8, 1897August 18, 1965) was an American politician who served during the 1930s as the 27th and 29th governor of Wisconsin. La Follette first served as a Republican from 1931 until 1933, where he lost renomination in ...

. His TVA appointment was also aided by the persistent lobbying of his old law professor Frankfurter. .

The TVA was established by Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

in 1933 for flood control and locally controlled hydroelectric power

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is Electricity generation, electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies 15% of the world's electricity, almost 4,210 TWh in 2023, which is more than all other Renewable energ ...

on the Tennessee River. It was a massive project controlled by a public corporation designed to modernize the rural, Southern communities within the Tennessee Valley. The TVA also established extensive education programs, and a library service that distributed books in the many rural hamlets that lacked a library. The TVA was locally and nationally controversial. On the national scale, opponents led by Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born Lewis Wendell Willkie; February 18, 1892 – October 8, 1944) was an American lawyer, corporate executive and the 1940 History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican nominee for president. Willkie appeale ...

said the TVA was a form of state socialism, and the other utility companies it competed against were also against the project. Local people were both apprehensive but also hopeful about the changes the TVA would bring.

In his role as one of the TVA directors, Lilienthal was skilled at administration and at creating supporters for the project.

In part due to his experience at the TVA, Lilienthal was often sent abroad to work on water development projects. Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after assassination of John F. Kennedy, the assassination of John F. Ken ...

dispatched him to the Mekong River

The Mekong or Mekong River ( , ) is a transboundary river in East Asia and Southeast Asia. It is the world's List of rivers by length, twelfth-longest river and List of longest rivers of Asia, the third-longest in Asia with an estimated l ...

to oversee development of a project there. He was also sent to India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

to report on the dispute between the two nations, for ''Collier's

}

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter F. Collier, Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened i ...

'' magazine. He thought that the Kashmir dispute was intractable, but there were other areas of mutual concern of the two nations were agreement could be found - such as the allotment of the water of the Indus River

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayas, Himalayan river of South Asia, South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in the Western Tibet region of China, flows northw ...

. He reported this idea to the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and Grant (money), grants to the governments of Least developed countries, low- and Developing country, middle-income countries for the purposes of economic development ...

, and its president, Eugene R. Black, agreed with the assessment. This led to the Indus Water Treaty, which to this day governs water allocation between India and Pakistan.

Atomic energy

Following theatomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

On 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, during World War II. The aerial bombings killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people, most of whom were civili ...

and the end of World War II and victory by the Allies, Lilienthal was fascinated and appalled by the information he soon absorbed about the power of the new weapon.

In January 1946, U.S. Under Secretary of State Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson ( ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American politician and lawyer. As the 51st United States Secretary of State, U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to ...

asked Lilienthal to chair a five-member panel of consultants to a committee including him and four others, who were to advise President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

and Secretary of State James F. Byrnes about the position of the United States at the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

on the new menace of nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s. At the time, the US held a monopoly on these weapons.

Lilienthal described the purpose of Acheson's request:

Those charged with foreign policy -- the Secretary of State (Byrnes) and the President -- did not have either the facts nor an understanding of what was involved in the atomic energy issue, the most serious cloud hanging over the world. Comments...have been made and are being made...without a knowledge of what the hell it is all about -- literally!Lilienthal quickly found out even more about the atomic weapon, and wrote in his journal:

No fairy tale that I read in utter rapture and enchantment as a child, no spy mystery, no "horror" story, can remotely compare with the scientific recital I listened to for six or seven hours today. ... I feel that I have been admitted, through the strangest accident of fate, behind the scenes in the most awful and inspiring drama since some primitive man looked for the very first time upon fire.The result of the panel was a 60-page ''Report on the International Control of Atomic Energy'', better known as the Acheson-Lilienthal Report. Released in March 1946, it proposed that the United States offer to turn over its monopoly on nuclear weapons to an international agency, in return for a system of strict inspections and control of

fissile materials

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material that can undergo nuclear fission when struck by a neutron of low energy. A self-sustaining thermal chain reaction can only be achieved with fissile material. The predominant neutron energy in ...

. It was a bold attempt to formulate a workable idea for international control (and implicitly assumed that the United States was far ahead of the Soviet Union in atomic weapons development and could remain in that position even if the Soviets violated the agreement).LaFeber, p. 447. However Truman then decided to appoint Bernard Baruch

Bernard Mannes Baruch (August 19, 1870 – June 20, 1965) was an American financier and statesman.

After amassing a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange, he impressed President Woodrow Wilson by managing the nation's economic mobilization in W ...

to present the plan to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

; Baruch changed some provisions of it, ending up with a proposal that the Soviets could not accept and that was vetoed by them. (As it happened, the Soviets were determined to proceed with their own atomic bomb program and were unlikely to accept either plan.)

Subsequently, the United States established the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to provide civilian control of this resource. Lilienthal was appointed as chair of the AEC on October 28, 1946, and served until February 15, 1950, one of the pioneers of civilian control of the American atomic energy program. He intended to administer a program that would "harness the atom" for peaceful purposes, principally atomic power. Lilienthal gave high priority to peaceful uses, especially nuclear power plants. However coal was cheap and the power industry was not interested. The first plant was begun under Eisenhower in 1954.

As chairman of the AEC in the late 1940s, during the early years of the

Subsequently, the United States established the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to provide civilian control of this resource. Lilienthal was appointed as chair of the AEC on October 28, 1946, and served until February 15, 1950, one of the pioneers of civilian control of the American atomic energy program. He intended to administer a program that would "harness the atom" for peaceful purposes, principally atomic power. Lilienthal gave high priority to peaceful uses, especially nuclear power plants. However coal was cheap and the power industry was not interested. The first plant was begun under Eisenhower in 1954.

As chairman of the AEC in the late 1940s, during the early years of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, Lilienthal played an important role in managing relations between the scientific community and the U.S. Government. The AEC was responsible for managing atomic energy development for the military as well as for civilian use. Lilienthal was responsible for ensuring that the Commander-in-Chief would have the use of a number of working atomic bombs. Lilienthal did not have as much enthusiasm for this task as some in Washington, and in particular he received steady criticism from Senators Brien McMahon

Brien McMahon (born James O'Brien McMahon) (October 6, 1903July 28, 1952) was an American lawyer and politician who served in the United States Senate (as a Democrat from Connecticut) from 1945 to 1952. McMahon was a major figure in the estab ...

and Bourke B. Hickenlooper, the chairman and ranking member of the United States Congress Joint Committee on Atomic Energy

The Joint Committee on Atomic Energy (JCAE) was a United States congressional committee that was tasked with exclusive jurisdiction over "all bills, resolutions, and other matters" related to civilian and military aspects of nuclear power from 194 ...

, for not pursuing the task with sufficient vigor. Indeed, in 1949 Hickenlooper raised charges that Lilienthal had engaged in "incredible mismanagement" and tried to have him removed as chairman; Lilienthal was cleared of wrongdoing but was left politically weakened within Washington.

Once the Soviet Union had successfully tested its own atomic bomb, Lilienthal became a central figure in the August 1949–January 1950 debate within the U.S. government and scientific community over whether to proceed with development of the hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lo ...

. President Truman appointed a three-person special committee, composed of Secretary of State Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson ( ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American politician and lawyer. As the 51st United States Secretary of State, U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to ...

and Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson in addition to Lilienthal as head of the AEC, to formulate a report to him on the matter.Holloway, p. 301. Lilienthal was opposed to development, stating among other reasons that the proposed weapon lacked a clear political or strategic rationale and that being overly dependent upon nuclear forces (rather than maintaining strong conventional forces) was an unwise security posture. But Lilienthal failed to marshal bureaucratic support for his position, in part due to the limitations of secrecy preventing him from finding allies and in part due to his repeated arguments losing their effectiveness. The three-person committee made its recommendation to proceed to Truman in a meeting on January 31, 1950, and the president so ordered. (Lilienthal ended up appearing to support the recommendation on the surface while trying to register a dissent as well, a confused situation that only became more so with additional memoranda filed after the fact and with conflicting recollections among the participants in years to follow.)

In his 1963 book, ''Change, Hope and the Bomb'', Lilienthal criticized nuclear developments, denouncing the nuclear industry's failure to have addressed the dangers of nuclear waste. He suggested that a civil atomic energy program should not be pursued until the "substantial health hazards involved were eliminated". Lilienthal argued that it would be "particularly irresponsible to go ahead with the construction of full scale nuclear power plants without a safe method of nuclear waste disposal having been demonstrated". However, Lilienthal stopped short of a blanket rejection of nuclear power. His view was that a more cautious approach was necessary.Wolfgang Rudig (1990). ''Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy'', Longman, p. 61.

Lilienthal as businessman

Lilienthal's resignation from the Atomic Energy Commission took effect on February 15, 1950. He was concerned that after years of relatively low-paying public service, he needed to make some money to provide for his wife and two children, and to secure funds for his retirement. After undertaking a lecture tour, he worked for several years as an industrial consultant for the investment bank Lazard Freres. Later he wrote about this period in his journal:A serene life apparently isn't the thing I crave. I live on enthusiasm, zest; and when I don't feel it, the bottom sags below sea level, and it is agony, no less.In 1955, he formed an engineering and consulting firm called Development and Resources Corporation (D&R), which shared some of the TVA's objectives: major public power and public works projects. Lilienthal leveraged the financial backing of Lazard Freres to found his company. He hired former associates from the TVA to work with him. D&R focused on overseas clients, including the

Khuzistan

Khuzestan province () is one of the 31 Provinces of Iran. Located in the southwest of the country, the province borders Iraq and the Persian Gulf, covering an area of . Its capital is the city of Ahvaz. Since 2014, it has been part of Iran's ...

region of Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, the Cauca Valley of Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

, Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, southern Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

, Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

, Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

, and South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam (RVN; , VNCH), was a country in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975. It first garnered Diplomatic recognition, international recognition in 1949 as the State of Vietnam within the ...

.

Lilienthal as writer

In May 1917, as a 17-year-old college freshman, Lilienthal met a young lawyer inGary, Indiana

Gary ( ) is a city in Lake County, Indiana, United States. The population was 69,093 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it Indiana's List of municipalities in Indiana, eleventh-most populous city. The city has been historical ...

. He later recalled that the lawyer

noticed how seriously I was looking at life in general and suggested as a remedy for this and as a source of amusement and self-cultivation the keeping of a diary of a different sort than the "ate today" "was sick yesterday" variety, but rather a record of the impressions I received from various sources; my reactions to books, people, events; my opinions and ideas on religion, sex, etc. The idea appealed to me at once.Lilienthal kept such a journal until the end of his life. In 1959, Lilienthal's son-in-law Sylvain Bromberger suggested that he consider publishing his private journals. Lilienthal wrote to Cass Canfield at

Harper & Row

Harper is an American publishing house, the flagship imprint of global publisher HarperCollins, based in New York City. Founded in New York in 1817 by James Harper and his brother John, the company operated as J. & J. Harper until 1833, when ...

; the company eventually published his journals in seven volumes, appearing between 1964 and 1983. They received largely positive reviews.

Lilienthal's other books include ''TVA: Democracy on the March'' (1944), ''This I Do Believe'' (1949), ''Big Business: A New Era'' (1953) and ''Change, Hope and the Bomb'' (1963).

Last years

His company D&R struggled financially during Lilienthal's final years. A promised infusion of capital from theRockefeller family

The Rockefeller family ( ) is an American Industrial sector, industrial, political, and List of banking families, banking family that owns one of the world's largest fortunes. The fortune was made in the History of the petroleum industry in th ...

was not fully realized. The company was dissolved in the late 1970s.

Lilienthal resided in Princeton, New Jersey

The Municipality of Princeton is a Borough (New Jersey), borough in Mercer County, New Jersey, United States. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton, New Jersey, Borough of Princeton and Pri ...

during his final years. In 1980, Lilienthal had two separate serious health problems. He had a bilateral hip replacement

Hip replacement is a surgery, surgical procedure in which the hip joint is replaced by a prosthetic implant (medicine), implant, that is, a hip prosthesis. Hip replacement surgery can be performed as a total replacement or a hemi/semi(half) repl ...

and cataract surgery

Cataract surgery, also called lens replacement surgery, is the removal of the natural lens (anatomy), lens of the human eye, eye that has developed a cataract, an opaque or cloudy area. The eye's natural lens is usually replaced with an artific ...

in one eye. He needed crutches and a cane at various points. The recovery period from the eye surgery forced him to neither read nor write aside from his final journal entry on January 2, 1981.

He died on January 16, 1981. News of his death, and his obituary, appeared on the front page of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

''.

Awards and honors

In 1951 Lilienthal was awarded thePublic Welfare Medal

The Public Welfare Medal is awarded by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences "in recognition of distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare." It is the most prestigious honor conferred by the academy. First awar ...

from the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

, of which he was also an elected member. He was also a member of both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

and the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

.

During his lifetime Lilienthal received honorary degrees from Boston University

Boston University (BU) is a Private university, private research university in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. BU was founded in 1839 by a group of Boston Methodism, Methodists with its original campus in Newbury (town), Vermont, Newbur ...

, DePauw University

DePauw University ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Greencastle, Indiana, United States. It was founded in 1837 as Indiana Asbury College and changed its name to DePauw University in 1884. The college has a Methodist heritage and was ...

, Lehigh University

Lehigh University (LU), in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, United States, is a private university, private research university. The university was established in 1865 by businessman Asa Packer. Lehigh University's undergraduate programs have been mixed ...

, and Michigan State College

Michigan State University (Michigan State or MSU) is a public land-grant research university in East Lansing, Michigan, United States. It was founded in 1855 as the Agricultural College of the State of Michigan, the first of its kind in the c ...

.

Notes

References

* * Hewlett, Richard G., and Oscar Edward Anderson. ''A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission: The New World, 1939-1946'' . Vol. 1. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1962. * * Hewlett, Richard G., and Oscar Edward Anderson. ''A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission: Volume II, Atomic shield 1947/1952'' (1969) * * * * Neuse, Steven M. "David E. Lilienthal: Exemplar of public purpose." ''International Journal of Public Administration'' 14.6 (1991): 1099–1148. * * * *Primary sources

* * * Lilienthal, David. (1944). ''TVA: Democracy on the March''.Further reading

*Brooks, John. (1963-2014). ''Business Adventures: Twelve Classic Tales from the World of Wall Street''. Chapter 9: "A Second Sort of Life, David E. Lilienthal Businessman". Open Road Media. . * Ekbladh, David. (2002). "'Mr. TVA': Grass-Roots Development, David Lilienthal, and the Rise and Fall of the Tennessee Valley Authority as a Symbol for U.S. Overseas Development, 1933–1973". ''Diplomatic History'', 26(3), 335–374. * Ekbladh, David. (2008). "Profits of Development: The Development and Resources Corporation and Cold War Modernization". ''Princeton University Library Chronicle'', 69(3), 487–505. * Hargrove, Erwin E. (1994). ''Prisoner of Myth: The Leadership of the Tennessee Valley Authority, 1933–1990''. * Neuse, Steven M. ''David E. Lilienthal: The journey of an American liberal'' (Univ. of Tennessee Press, 1996), a scholarly biography. * Schwarz, Jordan A. ''The New Dealers: Power politics in the age of Roosevelt'' (Vintage, 2011) pp 195–248online

*Wang, Jessica. (1999). ''American Science in an Age of Anxiety''. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. .

External links

David E. Lilienthal Papers at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Lilienthal, David E. 1899 births 1981 deaths Lawyers from Chicago People from Morton, Illinois People from Michigan City, Indiana DePauw University alumni Harvard Law School alumni Franklin D. Roosevelt administration personnel Chairpersons of the United States Atomic Energy Commission Tennessee Valley Authority people American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent American people of Slovak-Jewish descent The Century Foundation Members of the American Philosophical Society Delta Upsilon members