Darius Couch on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

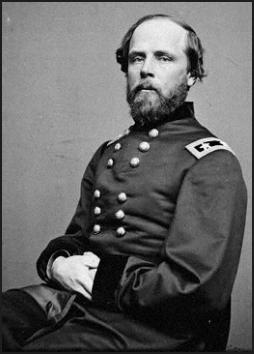

Darius Nash Couch (July 23, 1822 – February 12, 1897) was an American soldier, businessman, and

Couch then saw action with the U.S. Army during the

Couch then saw action with the U.S. Army during the

Couch led his division during the

Couch led his division during the

On November 14, 1862, Couch was assigned command of the II Corps, and he led it during the

On November 14, 1862, Couch was assigned command of the II Corps, and he led it during the

Following the Union defeat at Fredericksburg and the inglorious Mud March in January 1863, the commander of the Army of the Potomac—Couch's immediate superior—was again replaced. Maj. Gen.

Following the Union defeat at Fredericksburg and the inglorious Mud March in January 1863, the commander of the Army of the Potomac—Couch's immediate superior—was again replaced. Maj. Gen.

Couch returned to civilian life in Taunton after the war, where he ran unsuccessfully as a Democratic candidate for

Couch returned to civilian life in Taunton after the war, where he ran unsuccessfully as a Democratic candidate for

Vol. 1

an

Vol. 2

of the 1908.

€”

civilwarhome.com

Couch's official reports for the Fredericksburg Campaign.

''Massachusetts in the War, 1861–1865''

Springfield, MA: C. W. Bryan & Co., 1888. . *

Darius Couch

€”Georgia's Blue and Gray Trail site biography;

at historycentral.com * Photo gallery of Couch at www.generalsandbrevets.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Couch, Darius N. 1822 births 1897 deaths American military personnel of the Mexican–American War 19th-century American naturalists American people of the Seminole Wars Burials at Mount Pleasant Cemetery (Taunton, Massachusetts) Collectors of the Port of Boston Adjutants General of Connecticut Massachusetts Democrats Members of the Aztec Club of 1847 Military personnel from Connecticut People from Norwalk, Connecticut People from Southeast, New York People from Taunton, Massachusetts People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War Scientists from New York (state) Union army generals United States Military Academy alumni

naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

. He served as a career U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

officer during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

, the Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups of people collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Muscogee, Creek and Black Seminoles as well as oth ...

, and as a general officer

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

in the Union Army during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.

During the Civil War, Couch fought notably in the Peninsula

A peninsula is a landform that extends from a mainland and is only connected to land on one side. Peninsulas exist on each continent. The largest peninsula in the world is the Arabian Peninsula.

Etymology

The word ''peninsula'' derives , . T ...

and Fredericksburg campaigns of 1862, and the Chancellorsville and Gettysburg campaigns of 1863. He rose to command a corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was formally introduced March 1, 1800, when Napoleon ordered Gener ...

in the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

, and led divisions

Division may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

* Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting of 10,000 t ...

in both the Eastern Theater and Western Theater. Militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

under his command played a strategic role during the Gettysburg Campaign in delaying the advance of Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

troops of the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

and preventing their crossing the Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River ( ; Unami language, Lenape: ) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, crossing three lower Northeastern United States, Northeast states (New York, Pennsylvani ...

, critical to Pennsylvania's defense.

He has been described as personally courageous, very thin in build, and (after his time in Mexico) frail of health.

Early life and career

Couch was born in 1822 on a farm in the village ofSoutheast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, Radius, radially arrayed compass directions (or Azimuth#In navigation, azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A ''compass rose'' is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, ...

in Putnam County, New York

Putnam County is a County (New York), county in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 97,668. The county seat is Carmel (hamlet), New York, Carmel, within one of th ...

, and was educated at the local schools there.Warner, ''Generals in Blue'', p. 95. In 1842 he entered the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

, graduating four years later 13th out of 59 cadets. On July 1, 1846, Couch was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant and was assigned to the 4th U.S. Artillery.Eicher, ''Civil War High Commands'', p. 186.

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

, most notably in the Battle of Buena Vista

The Battle of Buena Vista (February 22–23, 1847), known as the Battle of La Angostura in Mexico, and sometimes as Battle of Buena Vista/La Angostura, was a battle of the Mexican–American War. It was fought between U.S. forces, largely vol ...

on February 22–23, 1847. For his actions on the second day of this fight, he was brevetted a first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

for "gallant and meritorious conduct." After the war ended in 1848 Couch began serving in garrison

A garrison is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a military base or fortified military headquarters.

A garrison is usually in a city ...

duty at Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe is a former military installation in Hampton, Virginia, at Old Point Comfort, the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula, United States. It is currently managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth o ...

in Hampton, Virginia

Hampton is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. The population was 137,148 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of cities in Virginia, seve ...

. The following year he was stationed at Fort Pickens, located near Pensacola, Florida

Pensacola ( ) is a city in the Florida panhandle in the United States. It is the county seat and only incorporated city, city in Escambia County, Florida, Escambia County. The population was 54,312 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. ...

, and then in Key West

Key West is an island in the Straits of Florida, at the southern end of the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it con ...

. Couch next participated in the Seminole Wars

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were a series of three military conflicts between the United States and the Seminoles that took place in Florida between about 1816 and 1858. The Seminoles are a Native American nation which co ...

during 1849 and into 1850.

Returning to garrison duty, later that year Couch was sent to Fort Columbus in New York Harbor

New York Harbor is a bay that covers all of the Upper Bay. It is at the mouth of the Hudson River near the East River tidal estuary on the East Coast of the United States.

New York Harbor is generally synonymous with Upper New York Bay, ...

, and in 1851 Couch was involved in recruiting at Jefferson Barracks

The Jefferson Barracks Military Post is located on the Mississippi River at Lemay, Missouri, south of St. Louis. It was an important and active U.S. Army installation from 1826 through 1946. It is the oldest operating U.S. military installatio ...

located on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

at Lemay, Missouri

Lemay is an Unincorporated area#United States, unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in south St. Louis County, Missouri, St. Louis County, Missouri, United States. The population was 16,645 at the 2010 census.

History

Lema ...

. Later in 1851 he returned to Fort Columbus, and then was ordered to Fort Johnston in Southport, North Carolina, staying there into 1852, and next in garrison at Fort Mifflin

Fort Mifflin, originally called Fort Island Battery and also known as Mud Island Fort, was commissioned in 1771 and sits on Mud Island (or Deep Water Island) on the Delaware River below Philadelphia, Pennsylvania near Philadelphia International ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

until 1853.

Couch then took a one-year leave of absence from the army from 1853 to 1854 to conduct a scientific mission for the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

in northern Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

. There, he discovered the species that are known as Couch's kingbird and Couch's spadefoot toad.Heidler, ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War'', p. 505. Upon his return to the United States in 1854, Couch was ordered to Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, on detached service. Later that year he resumed garrison duty in Fort Independence at Castle Island along Boston Harbor

Boston Harbor is a natural harbor and estuary of Massachusetts Bay, located adjacent to Boston, Massachusetts. It is home to the Port of Boston, a major shipping facility in the Northeastern United States.

History 17th century

Since its dis ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

. Also in 1854 he was stationed at Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

, Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

, and would remain there into the following year. On April 30, 1855, Couch resigned his commission in the U.S. Army. From 1855 to 1857 he was a merchant in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

. He then moved to Taunton, Massachusetts

Taunton is a city in and the county seat of Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. Taunton is situated on the Taunton River, which winds its way through the city on its way to Mount Hope Bay, to the south. As of the 2020 United States ...

, and worked as a copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

fabricator in the company owned by his wife's family. Couch was still working in Taunton when the American Civil War began in 1861.

American Civil War service

Early service

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Couch was appointed commander of the 7th Massachusetts Infantry on June 15, 1861, with the rank ofcolonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

in the Union Army. That August he was promoted to brigadier general with an effective date back to May 17. He was given brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military unit, military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute ...

command in the Military Division then Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

that fall, and Couch was given divisional command in the VI Corps in the following spring. From July 1861 to March 1862 he helped prepare and then maintain the defenses of Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

He participated in the Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula campaign (also known as the Peninsular campaign) of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March to July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The oper ...

, fighting in the Siege of Yorktown

The siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown and the surrender at Yorktown, was the final battle of the American Revolutionary War. It was won decisively by the Continental Army, led by George Washington, with support from the Ma ...

on April 5–May 4 and the Battle of Williamsburg

The Battle of Williamsburg, also known as the Battle of Fort Magruder, took place on May 5, 1862, in York County, James City County, and Williamsburg, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the first pitc ...

the following day.

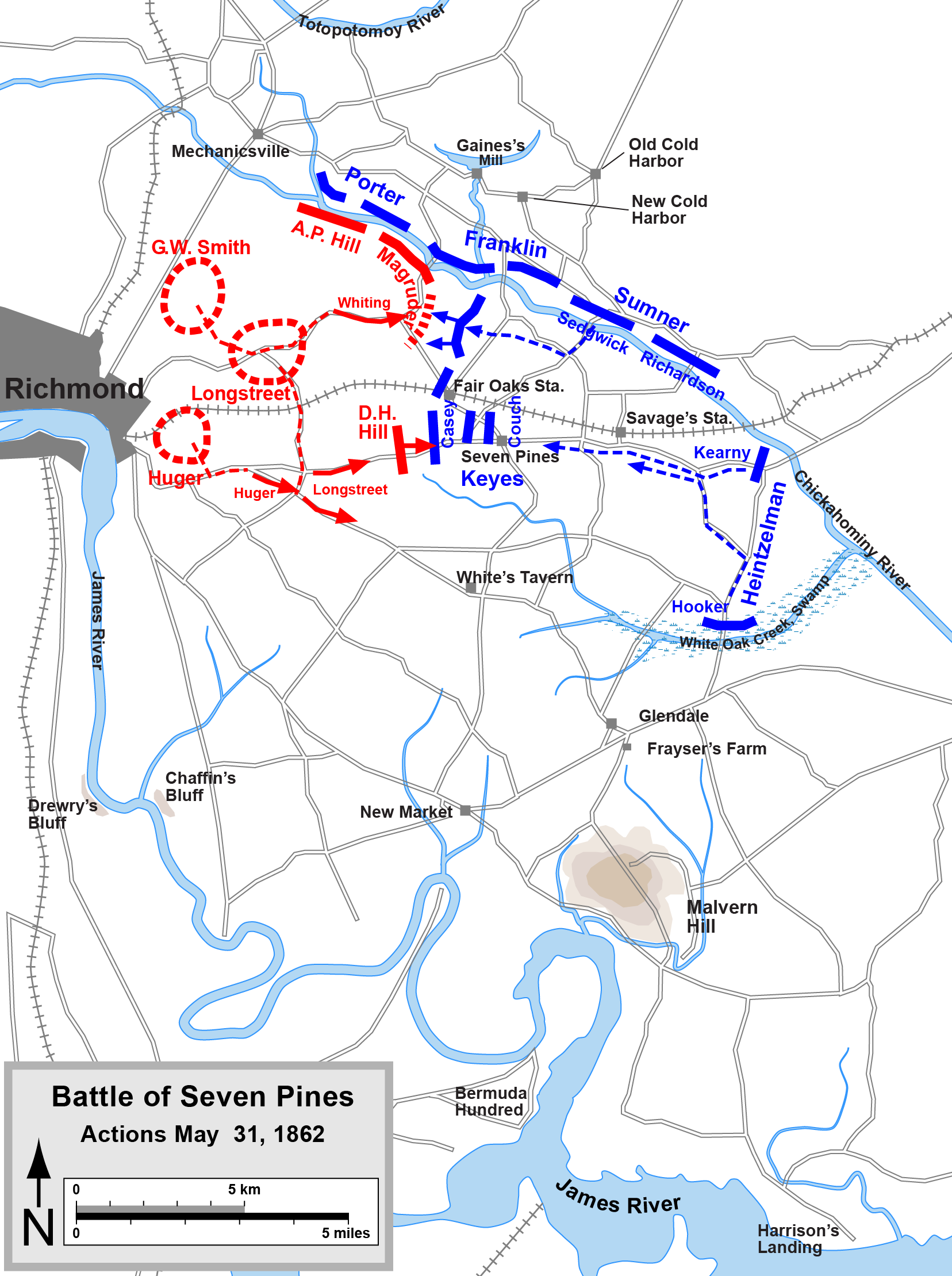

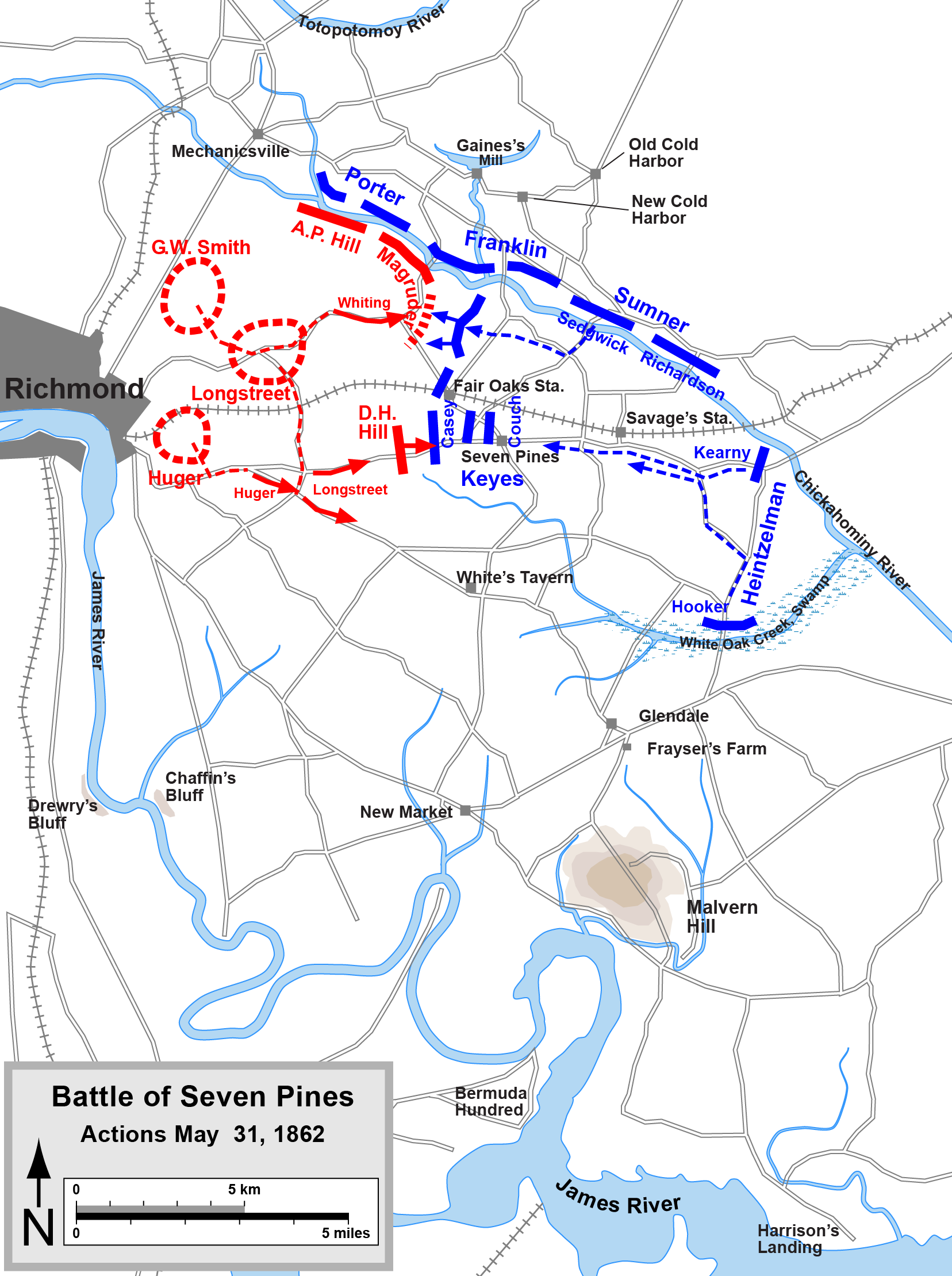

Seven Pines

Couch led his division during the

Couch led his division during the Battle of Seven Pines

The Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks or Fair Oaks Station, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War.

The Union's Army of the Po ...

on May 31 and June 1, 1862. In this engagement his corps commander, Brig. Gen. Erasmus D. Keyes, ordered Couch's division and that of Brig. Gen. Silas Casey forward of the Union defensive line, Couch's men right behind those of Casey. This placed the IV Corps in an isolated position, vulnerable to attack on three sides; however poorly coordinated Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

movements allowed Couch and Casey to partially prepare entrenchments against the impending assault. As the fighting continued throughout May 31 both Couch and Casey were slowly driven back, with their right flank units in the most peril. At this time Couch counterattacked with his old 7th Massachusetts Infantry and the 62nd New York Infantry in an attempt to bolster that side, however he did not succeed and was forced back, as was the rest of the Union IV Corps by nightfall.

Couch continued to lead his division during the 1862 Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate States Army, Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army ...

that followed, fighting in the Battle of Oak Grove on June 25 and the Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1. Later in July Couch's health began to fail, prompting him to offer his resignation. The army commander, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey and as Commanding General of the United States Army from November 1861 to March 186 ...

, refused to send it to the U.S. War Department, and instead Couch was promoted to major general, to date from July 4. Couch was involved in the Maryland Campaign

The Maryland campaign (or Antietam campaign) occurred September 4–20, 1862, during the American Civil War. The campaign was Confederate States Army, Confederate General (CSA), General Robert E. Lee's first invasion of the Northern United Stat ...

that fall, although absent from the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam ( ), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virgi ...

on September 17.

Fredericksburg

On November 14, 1862, Couch was assigned command of the II Corps, and he led it during the

On November 14, 1862, Couch was assigned command of the II Corps, and he led it during the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat between the Union Army, Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Major general ( ...

as part of Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner's "Right Grand Division". In this fight Couch's corps contained three divisions, led by Brig. Gens. Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

, Oliver Otis Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men again ...

, and William H. French. Early on December 12 infantry from his corps attempted to support the Union engineers' efforts to lay pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge (or ponton bridge), also known as a floating bridge, is a bridge that uses float (nautical), floats or shallow-draft (hull), draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the support ...

s across the Rappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 It traverses the enti ...

and into the town. When Confederate fire repeatedly prevented this, and a heavy artillery bombardment failed as well, the decision was made to send small groups of soldiers across in pontoon boats to dislodge the defenders. This amphibious assault

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducte ...

, which finally succeeded in driving out the Confederates, was executed by one of Couch's brigades under Col. Norman J. Hall (3rd Brigade, 2nd Division – 19th & 20th Massachusetts, 7th Michigan, 42nd & 59th New York, & 127th Pennsylvania).

As the Union soldiers entered a smoldering Fredericksburg they began to sack

A sack usually refers to a rectangular-shaped bag.

Sack may also refer to:

Bags

* Flour sack

* Gunny sack

* Hacky sack, sport

* Money sack

* Paper sack

* Sleeping bag

* Stuff sack

* Knapsack

Other uses

* Bed, a slang term

* Sack (band), ...

the city, forcing Couch to order his provost guard to secure the bridges and collect the loot. The next day his corps was ordered to attack the Confederate position at the base of Marye's Heights above Fredericksburg. To better watch his men's progress Couch entered the town's courthouse and climbed its cupola

In architecture, a cupola () is a relatively small, usually dome-like structure on top of a building often crowning a larger roof or dome. Cupolas often serve as a roof lantern to admit light and air or as a lookout.

The word derives, via Ital ...

, where he could see French's division advancing. As they approached the Confederate defenses, Couch could see his men taking very heavy fire and easily repulsed, described "as if the division had simply vanished." Hancock's division followed that of French, meeting the same fate with high casualties as well. Howard, who was to go in next, was with Couch as Hancock's division attacked. Briefly through the smoke they could see the mounting casualties, and Couch reportedly said, "Oh, great God! See how our men, our poor fellows, are falling."

Couch ordered Howard to march his division toward the right and possibly flank

Flank may refer to:

* Flank (anatomy), part of the abdomen

** Flank steak, a cut of beef

** Part of the external anatomy of a horse

* Flank speed, a nautical term

* Flank opening, a chess opening

* A term in Australian rules football

* The ...

the Confederate defenses his other two divisions had failed to dislodge. However the terrain did not permit any force that was marching from Fredericksburg toward Marye's Heights to attack anywhere other than at the stone wall along its base. When Howard's men attacked they were crowded back to the left, meeting the same resistance, and were repulsed. As other Union soldiers followed the II Corps in, Couch ordered his artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

to move into the field and blast the Confederates at close range. When his own artillery chief protested against exposing the gun crews in this fashion, Couch stated that he agreed but it was necessary to slow the Confederate fire in some way. The cannon stopped about 150 yards from the stone wall and opened fire, but quickly lost most of their crews and did little to slacken the enemy fire. During this time Couch moved slowly along his line of men, who were on the ground firing as best they could until nightfall. Recounting the attack on the heights on December 13, Couch wrote after the war:

In the attack Couch's force suffered heavily, as did the rest of the Right Grand Division. He reported that the II Corps sustained over four thousand casualties during the Fredericksburg Campaign. French's division lost an estimated 1,200 soldiers and Hancock around 2,000. Howard lost about 850 men, 150 of which were hit on December 11 supporting the engineers at the river. That night the Union wounded remained in the field, and Couch wrote after the war what he saw: "It was a night of dreadful suffering. Many died of wounds & exposure, and as fast as men died they stiffened in the wintry air, & on the front line were rolled forward for protection to the living. Frozen men were placed for dumb sentries."

Chancellorsville

Following the Union defeat at Fredericksburg and the inglorious Mud March in January 1863, the commander of the Army of the Potomac—Couch's immediate superior—was again replaced. Maj. Gen.

Following the Union defeat at Fredericksburg and the inglorious Mud March in January 1863, the commander of the Army of the Potomac—Couch's immediate superior—was again replaced. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everts Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the American Civil War and a three-time Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successfu ...

was relieved and Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

named to his place. Hooker reorganized the army and drew up plans for a new campaign against the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

. He wished to avoid attacking the Confederate defenses at Fredericksburg and sought to flank them out of position, thereby fighting on more open ground. After the reorganization Couch continued to lead the II Corps, with his divisions commanded by Hancock and French (both now major generals) and Brig. Gen. John Gibbon

John Gibbon (April 20, 1827 – February 6, 1896) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.

Early life

Gibbon was born in the Holmesburg, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Holmesburg section ...

at the head of Howard's former division, a total of about 17,000 soldiers.

During the ensuing Chancellorsville Campaign Couch was the senior corps commander, making him Hooker's second-in-command. In late April, Hooker began moving his corps across the Rappahannock and Rapidan River

The Rapidan River, flowing U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 through north-central Virginia in the United States, is the largest tributary of the Rappahannoc ...

s, ordering two of Couch's divisions to entrench and defend the Banks's Ford crossing of the Rappahannock and detach Gibbon's 5,000 men to remain at the Union camp back at Falmouth on April 29. The following day Couch had cleared the ford and was marching toward Chancellorsville. In the afternoon of May 1 Hooker—normally quite aggressive—cautiously slowed his marching army, and soon he stopped their movement altogether, despite some success against the Confederates and the loud protests of his corps commanders. Couch sent Hancock's division to bolster the Union men already engaged, and informed Hooker they could handle the enemy in front of them. However, Hooker's orders stood; march back into the positions they held the previous day and assume a defensive posture. Couch complied and ordered Hancock's division to form a rear guard

A rearguard or rear security is a part of a military force that protects it from attack from the rear, either during an advance or withdrawal. The term can also be used to describe forces protecting lines, such as communication lines, behind an ...

as they withdrew. As Hancock formed his men, Couch could see Confederate artillery aiming for the massed Union columns, and he told his staff "Let us draw their fire." The group of mounted officers clustered around a clearing where the enemy cannon could easily view them, thus attracting their fire and sparing the marching infantry; Couch and his staff also went unharmed. By nightfall the Union soldiers were busy fortifying the ground. Couch formed his divisions behind the XII Corps in roughly the center of Hooker's line.

By late afternoon on May 2, Hooker's line was hit on the right (the XI Corps led by Howard) by Confederates under Lt. Gen. Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson, and despite resisting the XI Corps was routed and ran toward Chancellorsville. The remaining corps tightened into a U-shaped formation by May 3, and Confederate artillery began shelling their positions, including Couch's men. At about 9 a.m. that day Hooker was stunned by enemy fire when a shell hit the pillar he was leaning on, temporarily incapacitating him within an hour. At that time Hooker turned command of the army over to Couch, and through consulting with a "groggy" Hooker it was decided to withdraw the army to defensive lines to the north, with the other commanders (except an embarrassed Howard) strongly advocating an attack instead.

Gettysburg

Couch requested reassignment after quarreling with Hooker.President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

offered him command of the Army of the Potomac, but he declined, citing poor health. He commanded the newly created Department of the Susquehanna during the Gettysburg Campaign in 1863. Fort Couch in Lemoyne, Pennsylvania, was constructed under his direction and was named in his honor. Assigned to protect Harrisburg

Harrisburg ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the county seat, seat of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, Dauphin County. With a population of 50, ...

from a threatened attack by Confederates under Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, Couch directed militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

from his department to skirmish with enemy cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

elements at Sporting Hill, one of the war's northernmost engagements. Couch's militia then joined the pursuit of Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

's Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

into Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

after the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was a three-day battle in the American Civil War, which was fought between the Union and Confederate armies between July 1 and July 3, 1863, in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle, won by the Union, ...

.

Subsequent activities

Confederates again invaded Couch's Department of the Susquehanna in August 1864, as Brig. Gen. John McCausland burned the town ofChambersburg

Chambersburg is a borough in and the county seat of Franklin County, in the South Central region of Pennsylvania, United States. It is in the Cumberland Valley, which is part of the Great Appalachian Valley, and north of Maryland and the Ma ...

. In December, Couch returned to the front lines with an assignment to the Western Theater, where he commanded a division in the XXIII Corps of the Army of the Ohio

The Army of the Ohio was the name of two Union Army, Union armies in the American Civil War. The first army became the Army of the Cumberland and the second army was created in 1863.

History

1st Army of the Ohio

General Orders No. 97 appointed ...

in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign and for the remainder of the war. Couch finished his military service after the Carolinas Campaign in 1865.

Postbellum career and death

Couch returned to civilian life in Taunton after the war, where he ran unsuccessfully as a Democratic candidate for

Couch returned to civilian life in Taunton after the war, where he ran unsuccessfully as a Democratic candidate for Governor of Massachusetts

The governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the head of government of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The governor is the chief executive, head of the state cabinet and the commander-in-chief of the commonw ...

in 1865

Events

January

* January 4 – The New York Stock Exchange opens its first permanent headquarters at 10-12 Broad near Wall Street, in New York City.

* January 13 – American Civil War: Second Battle of Fort Fisher – Unio ...

. He later briefly served as president of a mining company in West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

. Couch moved to Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

in 1871, where he served as the Quartermaster General, and then Adjutant General, for the state militia until 1884. In 1888 he joined the Aztec Club of 1847

The Aztec Club of 1847 is a military society founded in 1847 by United States Army officers of the Mexican–American War. It is a male-only hereditary organization with membership of those who can trace a direct ancestral connection "based on ma ...

by right of his service in the Mexican War. He also joined the Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

The Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), formally the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (NSSAR), is a federally chartered patriotic organization. The National Society, a nonprofit corporation headquartered in Louisvi ...

in 1890.

He died in Norwalk, Connecticut

Norwalk is a city in Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States. The city, part of the New York metropolitan area, New York Metropolitan Area, is the List of municipalities of Connecticut by population, sixth-most populous city in Connecticut ...

. He was buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Taunton.

Legacy

According to Herman Hattaway and Michael D. Smith:Couch is best remembered as an able division and corps commander in the Army of the Potomac. His career occasionally was marred by personal traits of impatience and temper directed at both subordinates and superiors. He also suffered from prolonged bouts of ill health, which led to his acceptance of the post of department commander.In 2017, General Couch's portrait was featured on a mural in Lemoyne, Pennsylvania in commemoration of the defenses mounted in the town under his name during the Gettysburg campaign. The fort served as the last line of defense for Pennsylvania' capital city of Harrisburg. Couch is commemorated in the scientific names of two species of reptiles: '' Sceloporus couchii'' and '' Thamnophis couchii'', and one frog: '' Scaphiopus couchii''. He also has one bird species named for him: Couch's kingbird.

See also

* List of American Civil War generals (Union) *List of Massachusetts generals in the American Civil War

There were approximately 120 general officers from Massachusetts who served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. This list consists of generals who were either born in Massachusetts or lived in Massachusetts when they joined the army ( ...

* Massachusetts in the American Civil War

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts played a significant role in national events prior to and during the American Civil War (1861–1865). Massachusetts Republicans dominated the early antislavery movement during the 1830s, motivating activists ac ...

Citations

General and cited references

* Alexander, Edward P. ''Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander''. Edited by Gary W. Gallagher. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989. . * Catton, Bruce. ''Glory Road''. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1952. . * Dupuy, Trevor N., Curt Johnson, and David L. Bongard. ''The Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography''. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. . * Eicher, David J. ''The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. . * Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. . * Foote, Shelby. '' The Civil War: A Narrative''. Vol. 2, ''Fredericksburg to Meridian''. New York: Random House, 1958. . * Fredriksen, John C. ''Civil War Almanac''. New York: Checkmark Books, 2008. . * Gambone, A. M. ''Major General Darius Nash Couch: Enigmatic Valor''. Baltimore: Butternut & Blue, 2000. . * Heidler, David S., and Jeanne T. Heidler. "Darius Nash Couch." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Winkler, H. Donald. ''Civil War Goats and Scapegoats''. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing, 2008. . * ''The Union Army: A History of Military Affairs in the Loyal States, 1861–65—Records of the Regiments in the Union Army—Cyclopedia of Battles—Memoirs of Commanders and Soldiers''. Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Publishing, 1997. First published 1908 by Federal Publishing CompanyVol. 1

an

Vol. 2

of the 1908.

€”

Aztec Club of 1847

The Aztec Club of 1847 is a military society founded in 1847 by United States Army officers of the Mexican–American War. It is a male-only hereditary organization with membership of those who can trace a direct ancestral connection "based on ma ...

site biography of Couch.

civilwarhome.com

Couch's official reports for the Fredericksburg Campaign.

Further reading

* Bowen, James Lorenzo''Massachusetts in the War, 1861–1865''

Springfield, MA: C. W. Bryan & Co., 1888. . *

External links

Darius Couch

€”Georgia's Blue and Gray Trail site biography;

at historycentral.com * Photo gallery of Couch at www.generalsandbrevets.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Couch, Darius N. 1822 births 1897 deaths American military personnel of the Mexican–American War 19th-century American naturalists American people of the Seminole Wars Burials at Mount Pleasant Cemetery (Taunton, Massachusetts) Collectors of the Port of Boston Adjutants General of Connecticut Massachusetts Democrats Members of the Aztec Club of 1847 Military personnel from Connecticut People from Norwalk, Connecticut People from Southeast, New York People from Taunton, Massachusetts People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War Scientists from New York (state) Union army generals United States Military Academy alumni