Czech Resistance Movement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Czechoslovak resistance to the

The Czech resistance network that existed during the early years of the

The Czech resistance network that existed during the early years of the

The most famous act of the Czech and Slovak resistance was the

The most famous act of the Czech and Slovak resistance was the

German occupation

German-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the (armed forces) and the government of Nazi Germany at ...

of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was a partially-annexation, annexed territory of Nazi Germany that was established on 16 March 1939 after the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–1945), German occupation of the Czech lands. The protector ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

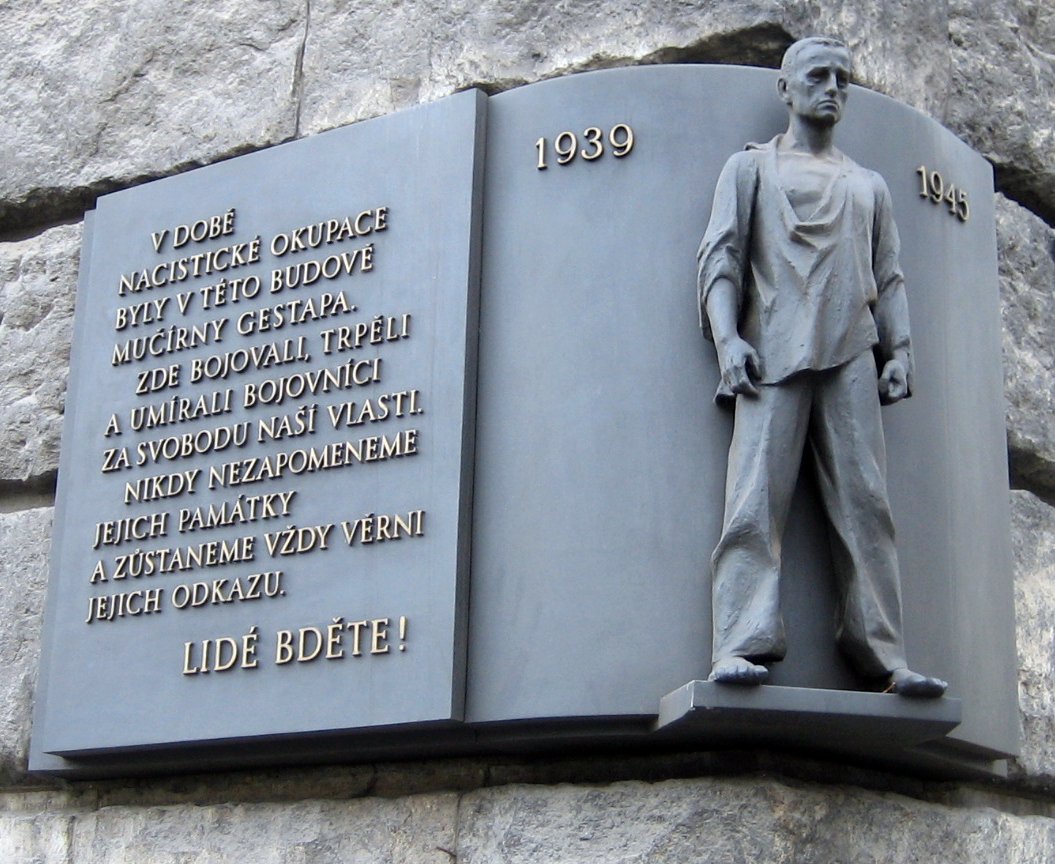

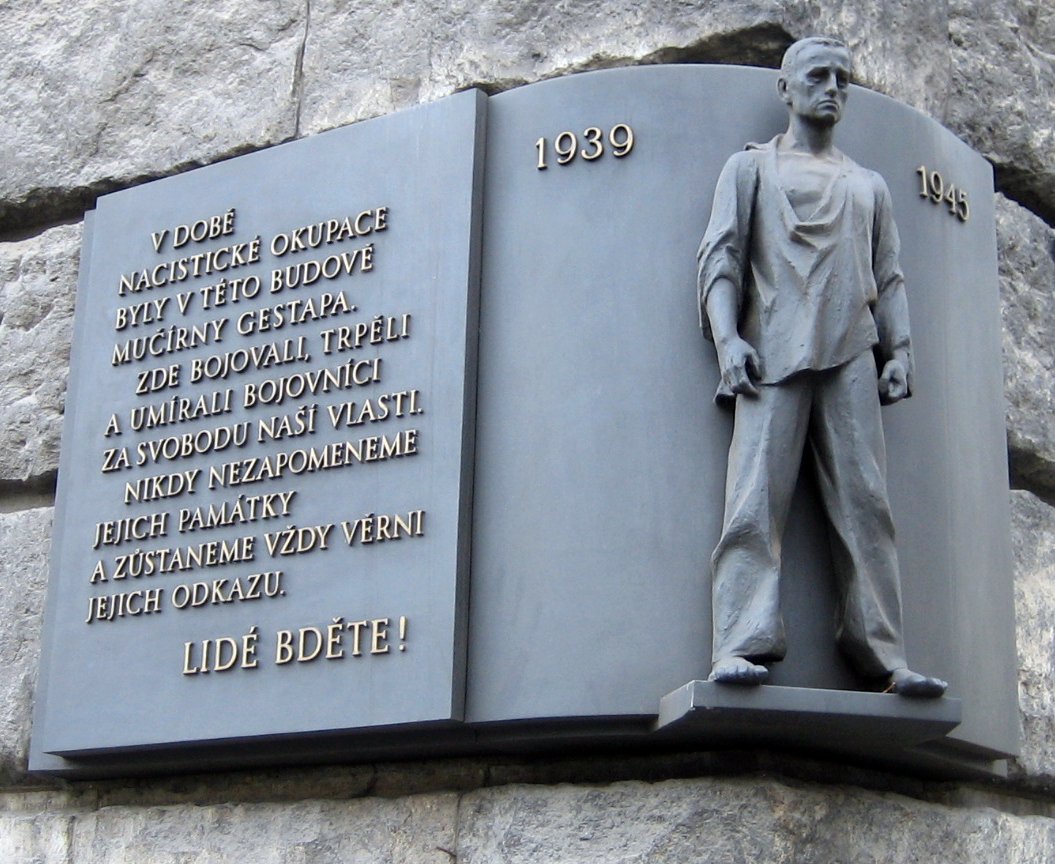

began after the occupation of the rest of Czechoslovakia and the formation of the protectorate on 15 March 1939. German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

policy deterred acts of resistance and annihilated organizations of resistance. In the early days of the war, the Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

population participated in boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent resistance, nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organisation, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for Morality, moral, society, social, politics, political, or Environmenta ...

s of public transport and large-scale demonstrations. Later on, armed communist partisan groups participated in sabotage and skirmishes with German police forces. The most well-known act of resistance was the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( , ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a German high-ranking SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust. He held the rank of SS-. Many historians regard Heydrich ...

. Resistance culminated in the so-called Prague uprising

The Prague uprising () was a partially successful attempt by the Czech resistance movement to liberate the city of Prague from German occupation in May 1945, during the end of World War II. The preceding six years of occupation had fuelled an ...

of May 1945; with Allied armies approaching, about 30,000 Czechs seized weapons. Four days of bloody street fighting ensued before the Soviet Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

entered the nearly liberated city.

Consolidation of resistance groups: ÚVOD

The Czech resistance network that existed during the early years of the

The Czech resistance network that existed during the early years of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

operated under the leadership of Czechoslovak president Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš (; 28 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was a Czech politician and statesman who served as the president of Czechoslovakia from 1935 to 1938, and again from 1939 to 1948. During the first six years of his second stint, he led the Czec ...

, who together with the head of Czechoslovak military intelligence, František Moravec, coordinated resistance activity while in exile in London. In the context of German persecution, the major resistance groups consolidated under the Central Leadership of Home Resistance (''Ústřední vedení odboje domácího'', ÚVOD). It served as the principal clandestine

Clandestine may refer to:

* Secrecy, the practice of hiding information from certain individuals or groups, perhaps while sharing it with other individuals

* Clandestine operation, a secret intelligence or military activity

Music and entertainmen ...

intermediary between Beneš and the Protectorate, which was in existence through 1941. Its long-term purpose was to serve as a shadow government until Czechoslovakia's liberation from Nazi occupation.

The three major resistance groups that consolidated under ÚVOD were the Political Centre (''Politické ústředí'', PÚ), the Committee of the Petition "We Remain Faithful" (''Petiční výbor Věrni zůstaneme'', PVVZ), and the Nation's Defence ('' Obrana národa'', ON). These groups were all democratic in nature, as opposed to the fourth official resistance group, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia ( Czech and Slovak: ''Komunistická strana Československa'', KSČ) was a communist and Marxist–Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992. It was a member of the Com ...

(KSČ). Most of their members were former officers of the disbanded Czechoslovak Army

The Czechoslovak Army (Czech and Slovak: ''Československá armáda'') was the name of the armed forces of Czechoslovakia. It was established in 1918 following Czechoslovakia's declaration of independence from Austria-Hungary.

History

In t ...

. In 1941, ÚVOD endorsed the political platform designed by the leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social hierarchies. Left-wing politi ...

group PVVZ, titled "For Freedom: Into a New Czechoslovak Republic". In it, ÚVOD professed allegiance to the democratic ideals of past Czechoslovak president Tomáš Masaryk

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (7 March 185014 September 1937) was a Czechoslovaks, Czechoslovak statesman, political activist and philosopher who served as the first List of presidents of Czechoslovakia, president of Czechoslovakia from 191 ...

, called for the establishment of a republic with socialist features, and urged all those in exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

to stay in step with the socialist advances at home.

In addition to serving as the means of communication between London and Prague, the ÚVOD was also responsible for the transmission of intelligence and military reports. It did so primarily through the use of a secret radio station, which could reach the Czech population. However, the ÚVOD was known to transmit inaccurate reports, whether false intelligence data or military updates. Sometimes this was intentional. Beneš often urged the ÚVOD to relay falsely optimistic reports of the military situation to improve morale or motivate more widespread resistance.

While the ÚVOD served as a principal aid to Beneš, it did sometimes depart from his policies. During the summer of 1941, the ÚVOD rejected Beneš' proposals for partial expulsion of the Sudeten Germans

German Bohemians ( ; ), later known as Sudeten Germans ( ; ), were ethnic Germans living in the Czech lands of the Bohemian Crown, which later became an integral part of Czechoslovakia. Before 1945, over three million German Bohemians constitute ...

after the conclusion of the war and instead demanded their complete expulsion. The ÚVOD succeeded in changing Beneš' official stance on this issue.

ÚVOD and the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ)

The ÚVOD's relationship with the KSČ was an important aspect of its daily functions, as Soviet-Czech relations became a central part of their resistance efforts. TheGerman invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along a ...

in June 1941 marked a turning point in Soviet-Czechoslovak relations. Before the invasion, "the main Communist objective was to stop the imperialist war" and was often sympathetic to the German workers of the Reich. After the invasion, the Resistance began to rely on communist support both within Czechoslovakia and from Moscow. In a broadcast from London on 24 June 1941 via the ÚVOD, Beneš informed his country that "the relationship between our two states thus returned to the pre-Munich situation and the old friendship."

While the KSČ was not an official part of the ÚVOD and kept its organisational independence, it called for unity of action with all anti-Fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

groups. Leaders of the KSČ ingratiated themselves with the ÚVOD by helping to maintain Soviet-Czechoslovak relations. Beneš often used these KSČ leaders to arrange meetings in Moscow to expand the Soviet-Czechoslovak partnership. There is some evidence that the ÚVOD may have warned the Russians about the German invasion in April 1941. In March 1941, Beneš received intelligence regarding a German build-up of troops on the Soviet Union's borders. According to his memoirs, he immediately passed on that information to the Americans, British and Soviet Union. The KSČ's fate was also closely linked with the ÚVOD's. It too suffered annihilation after the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Heydrich, the commander of the German Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), the acting governor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and a principal architect of the Holocaust, was assassinated during the Second World War in a coordin ...

, unable to rebound until 1944.

The Czechs and the Heydrich assassination

The most famous act of the Czech and Slovak resistance was the

The most famous act of the Czech and Slovak resistance was the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Heydrich, the commander of the German Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), the acting governor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and a principal architect of the Holocaust, was assassinated during the Second World War in a coordin ...

on 27 May 1942 by exiled Czech soldier Jan Kubiš

Jan Kubiš (24 June 1913 – 18 June 1942) was a Czech soldier, one of a team of Czechoslovak British-trained paratroopers sent to eliminate acting Reichsprotektor (Realm-Protector) of Bohemia and Moravia, SS-''Obergruppenführer'' Reinhard H ...

and Slovak Jozef Gabčík

Jozef Gabčík (; 8 April 1912 – 18 June 1942) was a Slovak soldier in the Czechoslovak Army involved in the Operation Anthropoid, the assassination of acting ''Reichsprotektor'' (Realm-Protector) of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ...

who had been parachuted into Bohemia by the British Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

. In many ways, the ÚVOD's demise was forecast with Heydrich's appointment as the ''Reichsprotektor

These are lists of political office-holders in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, which from 15 March 1939 until 9 May 1945 comprised the Nazi-occupied parts of Czechoslovakia.

The lists include both the representatives of the Nazi-rec ...

'' of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was a partially- annexed territory of Nazi Germany that was established on 16 March 1939 after the German occupation of the Czech lands. The protectorate's population was mostly ethnic Czechs.

After the ...

in the autumn of 1941. By the end of September, Heydrich had organised the arrest of nearly all members of the ÚVOD and successfully cut off all links between the ÚVOD and London.

The German reaction to Heydrich's assassination is often credited with the annihilation of an effective Czech underground movement after 1942. The Nazis exacted revenge, razing to the ground the two villages of Lidice

Lidice (; ) is a municipality and village in Kladno District in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 600 inhabitants.

Lidice is built near the site of the previous village, which was completely destroyed on 10 June 19 ...

and Ležáky. In October 1942, 1,331 people were sentenced to death by courts in the Protectorate, and 252 people were sent to Mauthausen for involvement with the assassination plot. Finally, in the wake of German revenge, the last remaining members of the ÚVOD were arrested.

Partisan warfare

The character of warfare changed dramatically after 1942. Partisan groups began to form in forested or mountainous areas. During the spring of 1945, partisan forces in Bohemia and Moravia had grown to 120 groups, with a combined strength of around 7,500 people. Partisans disrupted the railway and highway transportation by sabotaging track and bridges and attacking trains and stations. Some railways could not be used at night or on some days, and trains were forced to travel at a slower speed. There were more than 300 partisan attacks on rail communications from Summer 1944 to May 1945.Waffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

units retreating from the Red Army's advance into Moravia burned down entire villages as a reprisal. Partisan groups had a diverse membership including former members of Czech resistance groups fleeing arrest, escaped POWs, and German deserters. Other partisans were Czechs who lived in rural areas and continued with their jobs during the day, joining the partisans for night raids.

The largest and most successful group was the Jan Žižka partisan brigade, based in the Hostýn-Vsetín Mountains

Hostýn-Vsetín Mountains () is a mountain range in the Zlín Region of the Czech Republic.

The mountains are densely forested mainly by secondary spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' ( ), a genus of about 40 species of conifer ...

of southern Moravia. After crossing the border from Slovakia in September 1944, the Žižka brigade sabotaged railroads and bridges and raided the German police forces sent to hunt them down. Despite harsh countermeasures such as summary execution

In civil and military jurisprudence, summary execution is the putting to death of a person accused of a crime without the benefit of a free and fair trial. The term results from the legal concept of summary justice to punish a summary offense, a ...

of suspected civilian supporters, the partisans continued to operate. Eventually, the Žižka brigade grew to over 1,500 people and was operating in large parts of Moravia upon the liberation of the area in April 1945.

Prague uprising

On 5 May 1945, in the last moments of the war in Europe, citizens of Prague spontaneously attacked the occupiers and Czech resistance leaders emerged from hiding to guide them. German troops counterattacked, but progress was difficult due to the defection of theRussian Liberation Army

The Russian Liberation Army (; , ), also known as the Vlasov army () was a collaborationist formation, primarily composed of Russians, that fought under German command during World War II. From January 1945, the army was led by Andrey Vlasov, ...

and barricades constructed by the Czech citizenry. On 8 May, the Czech and German leaders signed a ceasefire allowing the German forces to withdraw from the city, but not all SS units obeyed. When the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

arrived on 9 May, the city was already almost liberated.

Because it was the largest Czech resistance action of the war, the Prague uprising became a national myth

A national myth is an inspiring narrative or anecdote about a nation's past. Such myths often serve as important national symbols and affirm a set of national values. A myth is entirely ficticious but it is often mixture with aspects of histori ...

for the new Czechoslovak nation after the war and has been a common subject of literature. After the 1948 coup, the memory of the uprising was distorted by the Communist regime for propaganda purposes.

Notable people

* Jan Morávek (1902–1984), Czech resistance memberSee also

*Ivančena

Ivančena is a stone cairn erected as a memorial for five Scouts, members of the , who were executed in April 1945 in Cieszyn, modern-day Poland, for their part in the Czech resistance to Nazi occupation during World War II. The monument is locat ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* {{Resistance in World War II by country World War II resistance movements Germany–Soviet Union relations (1918–1941) Czechoslovakia–Soviet Union relations