Czar Alexander II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was

The death of his father gave Alexander a diplomatic headache, for his father was engaged in open warfare in the southwest of his empire. On 15 January 1856, the new tsar took Russia out of the

The death of his father gave Alexander a diplomatic headache, for his father was engaged in open warfare in the southwest of his empire. On 15 January 1856, the new tsar took Russia out of the

The Emancipation Reform of 1861 abolished

The Emancipation Reform of 1861 abolished  Emancipation was not a simple goal capable of being achieved instantaneously by imperial decree. It contained complicated problems, deeply affecting the economic, social, and political future of the nation. Alexander had to choose between the different measures recommended to him and decide, if the serfs would become agricultural laborers dependent economically and administratively on the landlords, or if the serfs would be transformed into a class of independent communal proprietors. The emperor gave his support to the latter project, and the Russian peasantry became one of the last groups of peasants in Europe to shake off serfdom. The architects of the emancipation manifesto were Alexander's brother

Emancipation was not a simple goal capable of being achieved instantaneously by imperial decree. It contained complicated problems, deeply affecting the economic, social, and political future of the nation. Alexander had to choose between the different measures recommended to him and decide, if the serfs would become agricultural laborers dependent economically and administratively on the landlords, or if the serfs would be transformed into a class of independent communal proprietors. The emperor gave his support to the latter project, and the Russian peasantry became one of the last groups of peasants in Europe to shake off serfdom. The architects of the emancipation manifesto were Alexander's brother

Alexander's bureaucracy instituted an elaborate scheme of local self-government (

Alexander's bureaucracy instituted an elaborate scheme of local self-government (

Alexander maintained a generally liberal course. Radicals complained he did not go far enough, and he became a target for numerous assassination plots. He survived attempts that took place in 1866, 1879, and 1880. Finally , assassins organized by the

Alexander maintained a generally liberal course. Radicals complained he did not go far enough, and he became a target for numerous assassination plots. He survived attempts that took place in 1866, 1879, and 1880. Finally , assassins organized by the

The Russian Emperor succeeded in his diplomatic endeavors. Having secured agreement as to non-involvement by the other Great Powers, on 17 April 1877 Russia declared war upon the Ottoman Empire. The Russians, helped by the Romanian Army under its supreme commander King Carol I (then Prince of Romania), who sought to obtain Romanian independence from the Ottomans as well, were successful against the Turks and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 ended with the signing of the preliminary peace Treaty of San Stefano on . The treaty and the subsequent

The Russian Emperor succeeded in his diplomatic endeavors. Having secured agreement as to non-involvement by the other Great Powers, on 17 April 1877 Russia declared war upon the Ottoman Empire. The Russians, helped by the Romanian Army under its supreme commander King Carol I (then Prince of Romania), who sought to obtain Romanian independence from the Ottomans as well, were successful against the Turks and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 ended with the signing of the preliminary peace Treaty of San Stefano on . The treaty and the subsequent

The dying emperor was given Communion and

The dying emperor was given Communion and

In 1838–39, the young bachelor, Alexander made the Grand Tour of Europe which was standard for young men of his class at that time. One of the purposes of the tour was to select a suitable bride for himself. His father

In 1838–39, the young bachelor, Alexander made the Grand Tour of Europe which was standard for young men of his class at that time. One of the purposes of the tour was to select a suitable bride for himself. His father

On , Alexander II married his mistress Catherine Dolgorukova morganatically in a secret ceremony at

On , Alexander II married his mistress Catherine Dolgorukova morganatically in a secret ceremony at

(In Russian) * Knight of St. Andrew, ''29 April 1818'' * Knight of St. Alexander Nevsky, ''29 April 1818'' * Knight of St. Anna, 1st Class, ''29 April 1818'' * Knight of St. Vladimir, 1st Class, ''1 January 1846'' * Knight of St. George, 4th Class, ''10 November 1850''; 1st Class, ''26 November 1869'' * Knight of St. Stanislaus, 1st Class, ''11 June 1865'' * Golden Sword "For Bravery", ''28 November 1877'' *

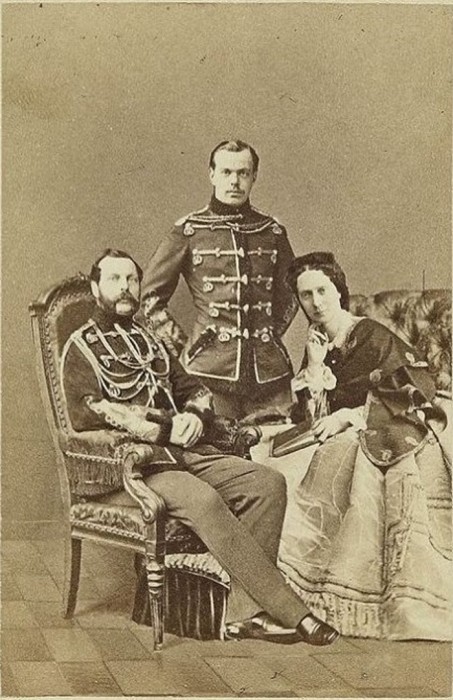

File:Alexander II by E.Botman (1856, Russian museum).jpg, Portrait of Alexander II, 1856

File:Alexander_II_of_Russia_by_Monogrammist_V.G._(1888,_Hermitage)_detail.jpg, Portrait of Emperor Alexander II wearing the greatcoat and cap of the Imperial Horse-Guards Regiment. c. 1865

File:Alexander_II_S_L_Levitsky.JPG, Alexander II, by Sergei Lvovich Levitsky, 1860 (The Di Rocco Wieler Private Collection, Toronto, Canada)

File:Alexander II of Russia by K.Makovskiy (1881, GTG).jpg, Alexander II, portrait by

excerpt and text search

* Lincoln, W. Bruce. '' The Great Reforms: Autocracy, Bureaucracy, and the Politics of Change in Imperial Russia'' (1990) * Moss, Walter G., ''Alexander II and His Times: A Narrative History of Russia in the Age of Alexander II, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky''. London: Anthem Press, 2002

online

* Mosse, W. E. ''Alexander II and the Modernization of Russia'' (1958

online

* Pereira, N.G.O.,''Tsar Emancipator: Alexander II of Russia, 1818–1881'', Newtonville, Mass: Oriental Research Partners, 1983. * * Radzinsky, Edvard, ''Alexander II: The Last Great Tsar''. New York: The Free Press, 2005. * Watts, Carl Peter. "Alexander II's Reforms: Causes and Consequences" ''History Review'' (1998): 6–15

Online

*

The Emperor Alexander II. Photos with dates.

The Assassination of Tsar Alexander II

from ''In Our Time'' (BBC Radio 4)

Alexander II – the Liberator. Russian-speaking forum.

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Alexander 02 Of Russia 1818 births 1881 deaths People murdered in 1881 19th-century Russian monarchs 19th-century Polish monarchs 19th-century murdered monarchs Burials at Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg Assassinated politicians from the Russian Empire Children of Nicholas I of Russia Circassian genocide perpetrators Deaths by suicide bomber Deaths from bleeding Extra Knights Companion of the Garter Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Grand Crosses of the Order of Aviz Grand Crosses of the Order of Christ (Portugal) Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint-Charles Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint James of the Sword Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary House of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov Knights Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa Knights Grand Cross of the Military Order of William Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain Murdered Russian monarchs Royalty from Moscow People from Moscow Governorate People murdered in Russia People of the Caucasian War Recipients of the Order of St. Anna, 1st class Recipients of the Order of St. George of the First Degree Recipients of the Order of the Netherlands Lion Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (military class) Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland) Heads of state of Finland Emperors of Russia Grand dukes of Russia Russian people of the Crimean War Russian people of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) Russian terrorism victims Sons of Russian emperors Assassinated heads of state in Europe Assassinated Russian politicians Politicians assassinated in the 1880s Deaths by explosive device

Emperor of Russia

The emperor and autocrat of all Russia (, ), also translated as emperor and autocrat of all the Russias, was the official title of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarch from 1721 to 1917.

The title originated in connection with Russia's ...

, King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of Royal elections in Poland, free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electab ...

and Grand Duke of Finland

The Grand Duke of Finland, alternatively the Grand Prince of Finland after 1802, was, from around 1580 to 1809, a title in use by most Swedish monarchs. Between 1809 and 1917, it was included in the title of the emperor of Russia, who was also t ...

from 2 March 1855 until his assassination in 1881. Alexander's most significant reform as emperor was the emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure Economic, social and cultural rights, economic and social rights, civil and political rights, po ...

of Russia's serfs in 1861, for which he is known as Alexander the Liberator ( rus, Алекса́ндр Освободи́тель, r=Aleksándr Osvobodítel, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ɐsvəbɐˈdʲitʲɪlʲ).

The tsar was responsible for other liberal reforms, including reorganizing the judicial system, setting up elected local judges, abolishing corporal punishment

A corporal punishment or a physical punishment is a punishment which is intended to cause physical pain to a person. When it is inflicted on Minor (law), minors, especially in home and school settings, its methods may include spanking or Padd ...

, promoting local self-government through the ''zemstvo

A zemstvo (, , , ''zemstva'') was an institution of local government set up in consequence of the emancipation reform of 1861 of Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexander II of Russia. Nikolay Milyutin elaborated the idea of the zemstvo, and the fi ...

'' system, imposing universal military service, ending some privileges of the nobility, and promoting university education. After an assassination attempt in 1866, Alexander adopted a somewhat more conservative stance until his death.

Alexander was also notable for his foreign policy, which was mainly pacifist, supportive of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, and opposed to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

. Alexander backed the Union during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

and sent warships to New York Harbor

New York Harbor is a bay that covers all of the Upper Bay. It is at the mouth of the Hudson River near the East River tidal estuary on the East Coast of the United States.

New York Harbor is generally synonymous with Upper New York Bay, ...

and San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

to deter attacks by the Confederate Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the Navy, naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the Amer ...

. He sold Alaska to the United States in 1867, fearing the remote colony would fall into British hands in a future war. He sought peace, moved away from bellicose France when Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

fell in 1871, and in 1872 joined with Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

in the League of the Three Emperors that stabilized the European situation.

Despite his otherwise pacifist foreign policy, he fought a brief war with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

in 1877–78, leading to the independence of Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

and Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

. He pursued further expansion into the Far East

The Far East is the geographical region that encompasses the easternmost portion of the Asian continent, including North Asia, North, East Asia, East and Southeast Asia. South Asia is sometimes also included in the definition of the term. In mod ...

, leading to the founding of Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( ; , ) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai and the capital of the Far Eastern Federal District of Russia. It is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, covering an area o ...

; into the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

, approving plans leading to the Circassian genocide;King, Charles. ''The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus''. p. 94. ''In a policy memorandum in of 1857, Dmitri Milyutin, chief-of-staff to Bariatinskii, summarized the new thinking on dealing with the northwestern highlanders. The idea, Milyutin argued, was not to clear the highlands and coastal areas of Circassians so that these regions could be settled by productive farmers... utRather, eliminating the Circassians was to be an end in itself – to cleanse the land of hostile elements. Tsar Alexander II

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland fro ...

formally approved the resettlement plan...Milyutin, who would eventually become minister of war, was to see his plans realized in the early 1860s.'' and into Turkestan

Turkestan,; ; ; ; also spelled Turkistan, is a historical region in Central Asia corresponding to the regions of Transoxiana and East Turkestan (Xinjiang). The region is located in the northwest of modern day China and to the northwest of its ...

. Although disappointed by the results of the Congress of Berlin

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the Russian Empire on the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878), which had ended the Rus ...

in 1878, Alexander abided by that agreement. Among his greatest domestic challenges was an uprising in Poland in 1863, to which he responded by stripping Poland of its separate constitution, incorporating it directly into Russia and abolishing serfdom there. Alexander was proposing additional parliamentary reforms to counter the rise of nascent revolutionary and anarchistic movements when he was assassinated in 1881.

Early life

Born inMoscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

, Alexander Nikolayevich was the eldest son of Nicholas I of Russia

Nicholas I, group=pron (Russian language, Russian: Николай I Павлович; – ) was Emperor of Russia, List of rulers of Partitioned Poland#Kings of the Kingdom of Poland, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 18 ...

and Charlotte of Prussia (eldest daughter of Frederick William III of Prussia

Frederick William III (; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, when the empire was dissolved ...

and of Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Luise Auguste Wilhelmine Amalie; 10 March 1776 – 19 July 1810) was Queen of Prussia as the wife of King Frederick William III. The couple's happy, though short-lived, marriage produced nine children, inclu ...

). His early life gave little indication of his ultimate potential; until the time of his accession in 1855, aged 37, few imagined that posterity would know him for implementing the most challenging reforms undertaken in Russia since the reign of Peter the Great

Peter I (, ;

– ), better known as Peter the Great, was the Sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia, Tsar of all Russia from 1682 and the first Emperor of Russia, Emperor of all Russia from 1721 until his death in 1725. He reigned j ...

.

His uncle Emperor Alexander I died childless. Grand Duke Konstantin, the next-younger brother of Alexander I, had previously renounced his rights to the throne of Russia. Thus, Alexander's father, who was the third son of Paul I, became the new Emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

; he took the name Nicholas I. At that time, Alexander became Tsesarevich

Tsesarevich (, ) was the title of the heir apparent or heir presumptive, presumptive in the Russian Empire. It either preceded or replaced the Eastern Slavic naming customs, given name and patronymic.

Usage

It is often confused with the much ...

as his father's heir to the throne.

In the period of his life as heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

(1825 to 1855), the intellectual atmosphere of Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

did not favour any kind of change: freedom of thought

Freedom of thought is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints.

Overview

Every person attempts to have a cognitive proficiency by developing knowledge, concepts, theo ...

and all forms of private initiative were suppressed vigorously by the order of his father. Personal and official censorship was rife; criticism of the authorities was regarded as a serious offence.

The education of the tsesarevich

Tsesarevich (, ) was the title of the heir apparent or heir presumptive, presumptive in the Russian Empire. It either preceded or replaced the Eastern Slavic naming customs, given name and patronymic.

Usage

It is often confused with the much ...

as future emperor took place under the supervision of the liberal romantic poet and gifted translator Vasily Zhukovsky, grasping a smattering of a great many subjects and becoming familiar with the chief modern European languages

There are over 250 languages indigenous to Europe, and most belong to the Indo-European language family. Out of a total European population of 744 million as of 2018, some 94% are native speakers of an Indo-European language. The three larges ...

. Unusually for the time, the young Alexander was taken on a six-month tour of Russia (1837), visiting 20 provinces in the country. He also visited many prominent Western European countries in 1838 and 1839. As Tsesarevich, Alexander became the first Romanov

The House of Romanov (also transliterated as Romanoff; , ) was the reigning dynasty, imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after Anastasia Romanovna married Ivan the Terrible, the first crowned tsar of all Russi ...

heir to visit Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

(1837). While touring Russia, he also befriended the then-exiled poet Alexander Herzen

Alexander Ivanovich Herzen (; ) was a Russian writer and thinker known as the precursor of Russian socialism and one of the main precursors of agrarian populism (being an ideological ancestor of the Narodniki, Socialist-Revolutionaries, Trudo ...

and pardoned him. It was through Herzen's influence that he later abolished serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

in Russia.

In 1839, when his parents sent him on a tour of Europe, he met twenty-year-old Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

and they became acquainted. Simon Sebag Montefiore speculates that a small romance emerged. Such a marriage, however, would not work, as Alexander was not a minor prince of Europe and was in line to inherit a throne himself. In 1847, Alexander donated money to Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

during the Great Famine.

He has been described as looking like a German, somewhat of a pacifist, a heavy smoker and card player. He spoke Russian and German.

Reign

The death of his father gave Alexander a diplomatic headache, for his father was engaged in open warfare in the southwest of his empire. On 15 January 1856, the new tsar took Russia out of the

The death of his father gave Alexander a diplomatic headache, for his father was engaged in open warfare in the southwest of his empire. On 15 January 1856, the new tsar took Russia out of the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

on the very unfavourable terms of the Treaty of Paris (1856)

The Treaty of Paris of 1856, signed on 30 March 1856 at the Congress of Paris (1856), Congress of Paris, brought an end to the Crimean War (1853–1856) between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the United Kingdom of G ...

, which included the loss of the Black Sea Fleet

The Black Sea Fleet () is the Naval fleet, fleet of the Russian Navy in the Black Sea, the Sea of Azov and the Mediterranean Sea. The Black Sea Fleet, along with other Russian ground and air forces on the Crimea, Crimean Peninsula, are subordin ...

, and the provision that the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

was to be a demilitarized zone similar to a contemporaneous region of the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

. This gave him room to breathe and pursue an ambitious plan of domestic reforms.

Reforms

Encouraged by public opinion, Alexander began a period of radical reforms, including an attempt not to depend on landed aristocracy controlling the poor, an effort to develop Russia's natural resources, and to reform all branches of the administration.Boris Chicherin

Boris Nikolayevich Chicherin (; 1828 – 1904) was a Russian jurist and political philosopher, who worked out a theory that Russia needed a strong, authoritative government to persevere with liberal reforms. By the time of the Russian Revolut ...

(1828–1904) was a political philosopher who believed that Russia needed a strong, authoritative government by Alexander to make the reforms possible. He praised Alexander for the range of his fundamental reforms, arguing that the tsar was:

Emancipation of the serfs

Alexander II succeeded to the throne upon the death of his father in 1855. As Tsesarevich, he had been an enthusiastic supporter of his father's reactionary policies. That is, he always obeyed the autocratic ruler. But now he was the autocratic ruler himself, and fully intended to rule according to what he thought best. He rejected any moves to set up a parliamentary system that would curb his powers. He inherited a large mess that had been wrought by his father's fear of progress during his reign. Many of the other royal families of Europe had also disliked Nicholas I, which extended to distrust of the Romanov dynasty itself. Even so, there was no one more prepared to bring the country around than Alexander II. The first year of his reign was devoted to the prosecution of theCrimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

and, after the fall of Sevastopol

Sevastopol ( ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea and a major port on the Black Sea. Due to its strategic location and the navigability of the city's harbours, Sevastopol has been an important port and naval base th ...

, to negotiations for peace led by his trusted counsellor, Prince Alexander Gorchakov. The country had been exhausted and humiliated by the war. Bribe-taking, theft and corruption were rampant.

The Emancipation Reform of 1861 abolished

The Emancipation Reform of 1861 abolished serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

on private estates throughout the Russian Empire. By this edict more than 23 million people received their liberty. Serfs gained the full rights of free citizens, including rights to marry without having to gain consent, to own property, and to own a business. The measure was the first and most important of the liberal reforms made by Alexander II.

Polish landed proprietor

In real estate, a landed property or landed estate is a property that generates income for the owner (typically a member of the gentry) without the owner having to do the actual work of the estate.

In medieval Western Europe, there were two compe ...

s of the Lithuanian provinces presented a petition hoping that their relations with the serfs might be regulated in a way more satisfactory for the proprietors. Alexander II authorized the formation of committees "for ameliorating the condition of the peasants", and laid down the principles on which the amelioration was to be effected. Without consulting his ordinary advisers, Alexander ordered the Minister of the Interior to send a circular to the provincial governors of European Russia

European Russia is the western and most populated part of the Russia, Russian Federation. It is geographically situated in Europe, as opposed to the country's sparsely populated and vastly larger eastern part, Siberia, which is situated in Asia ...

(serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

was rare in other parts) containing a copy of the instructions forwarded to the Governor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

of Lithuania, praising the supposed generous, patriotic intentions of the Lithuanian landed proprietors, and suggesting that perhaps the landed proprietors of other provinces might express a similar desire. The hint was taken: in all provinces where serfdom existed, emancipation committees were formed.

Emancipation was not a simple goal capable of being achieved instantaneously by imperial decree. It contained complicated problems, deeply affecting the economic, social, and political future of the nation. Alexander had to choose between the different measures recommended to him and decide, if the serfs would become agricultural laborers dependent economically and administratively on the landlords, or if the serfs would be transformed into a class of independent communal proprietors. The emperor gave his support to the latter project, and the Russian peasantry became one of the last groups of peasants in Europe to shake off serfdom. The architects of the emancipation manifesto were Alexander's brother

Emancipation was not a simple goal capable of being achieved instantaneously by imperial decree. It contained complicated problems, deeply affecting the economic, social, and political future of the nation. Alexander had to choose between the different measures recommended to him and decide, if the serfs would become agricultural laborers dependent economically and administratively on the landlords, or if the serfs would be transformed into a class of independent communal proprietors. The emperor gave his support to the latter project, and the Russian peasantry became one of the last groups of peasants in Europe to shake off serfdom. The architects of the emancipation manifesto were Alexander's brother Konstantin

The first name Konstantin () is a derivation from the Latin name '' Constantinus'' ( Constantine) in some European languages, such as Bulgarian, Russian, Estonian and German. As a Christian given name, it refers to the memory of the Roman empe ...

, Yakov Rostovtsev, and Nikolay Milyutin. On 3 March 1861, six years after his accession, the emancipation law was signed and published.

Additional reforms

A host of new reforms followed in diverse areas. The tsar appointed Dmitry Milyutin to carry out significant reforms in the Russian armed forces. Further important changes were made concerning industry and commerce, and the new freedom thus afforded produced a large number oflimited liability companies

A limited liability company (LLC) is the United States-specific form of a private limited company. It is a business structure that can combine the pass-through taxation of a partnership or sole proprietorship with the limited liability of a ...

. Plans were formed for building a great network of railways, partly to develop the natural resources of the country, and partly to increase its power for defense and attack.

Military reforms included universal conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

, introduced for all social classes on 1 January 1874. Prior to the new regulation, as of 1861, conscription was compulsorily enforced only for the peasantry. Conscription had been 25 years for serfs who were drafted by their landowners, which was widely considered to be a life sentence. Other military reforms included extending the reserve forces and the military district system, which split the Russian states into 15 military districts, a system still in use over a hundred years later. The building of strategic railways and an emphasis on the military education of the officer corps comprised further reforms. Corporal punishment

A corporal punishment or a physical punishment is a punishment which is intended to cause physical pain to a person. When it is inflicted on Minor (law), minors, especially in home and school settings, its methods may include spanking or Padd ...

in the military and branding of soldiers as punishment were banned. The bulk of important military reforms were enacted as a result of the poor showing in the Crimean War.

A new judicial administration (1864), based on the French model, introduced security of tenure. A new penal code

A criminal code or penal code is a document that compiles all, or a significant amount of, a particular jurisdiction's criminal law. Typically a criminal code will contain Crime, offences that are recognised in the jurisdiction, penalties that ...

and a greatly simplified system of civil and criminal procedure also came into operation. Reorganisation of the judiciary occurred to include trial in open court, with judges appointed for life, a jury system, and the creation of justices of the peace to deal with minor offences at local level. Legal historian Sir Henry Maine credited Alexander II with the first great attempt since the time of Grotius

Hugo Grotius ( ; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Hugo de Groot () or Huig de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, statesman, poet and playwright. A teenage prodigy, he was born in Delft an ...

to codify and humanise the usages of war.

Alexander's bureaucracy instituted an elaborate scheme of local self-government (

Alexander's bureaucracy instituted an elaborate scheme of local self-government (zemstvo

A zemstvo (, , , ''zemstva'') was an institution of local government set up in consequence of the emancipation reform of 1861 of Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexander II of Russia. Nikolay Milyutin elaborated the idea of the zemstvo, and the fi ...

) for the rural districts (1864) and the large towns (1870), with elective assemblies possessing a restricted right of taxation, and a new rural and municipal police under the direction of the Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

.

Under Alexander's rules Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

could not own land, and were restricted in travel. However special taxes on Jews were eliminated and those who graduated from secondary school were permitted to live outside the Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement was a western region of the Russian Empire with varying borders that existed from 1791 to 1917 (''de facto'' until 1915) in which permanent settlement by Jews was allowed and beyond which the creation of new Jewish settlem ...

, and became eligible for state employment. Large numbers of educated Jews moved as soon as possible to Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and other major cities.

The Alaska colony was losing money, and would be impossible to defend in wartime against Britain, so in 1867 Russia sold Alaska to the United States for $7.2 million (equivalent to $ million in ). The Russian administrators, soldiers, settlers, and some of the priests returned home. Others stayed to minister to their native parishioners, who remain members of the Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The Primate (bishop), p ...

into the 21st century.

Reaction after 1866

Narodnaya Volya

Narodnaya Volya () was a late 19th-century revolutionary socialist political organization operating in the Russian Empire, which conducted assassinations of government officials in an attempt to overthrow the autocratic Tsarist system. The org ...

(People's Will) party killed him with a bomb. The Emperor had earlier in the day signed the Loris-Melikov constitution, which would have created two legislative commissions made up of indirectly elected representatives, had it not been repealed by his reactionary successor Alexander III.

An attempted assassination in 1866 started a more conservative period that lasted until his death. The Tsar made a series of new appointments, replacing liberal ministers with conservatives. Under Minister of Education Dmitry Tolstoy, liberal university courses and subjects that encouraged critical thinking were replaced by a more traditional curriculum, and from 1871 onwards only students from gymnasiums could progress to university. In 1879, governor-generals were established with powers to prosecute in military courts and exile political offenders. The government also held show trials with the intention of deterring others from revolutionary activity, but after cases such as the Trial of the 193 where sympathetic juries acquitted many of the defendants, this was abandoned.

Suppression of separatist movements

After Alexander II became Emperor of Russia andKing of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of Royal elections in Poland, free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electab ...

in 1855, he substantially relaxed the strict and repressive regime that had been imposed on Congress Poland

Congress Poland or Congress Kingdom of Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It was established w ...

after the November Uprising

The November Uprising (1830–31) (), also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in Russian Partition, the heartland of Partitions of Poland, partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. ...

of 1830–1831.

However, in 1856, at the beginning of his reign, Alexander made a memorable speech to the deputies of the Polish nobility who inhabited Congress Poland

Congress Poland or Congress Kingdom of Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It was established w ...

, Western Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

, Livonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

, and Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

, in which he warned against further concessions with the words, "Gentlemen, let us have no dreams!" This served as a warning to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The territories of the former Poland-Lithuania were excluded from liberal policies introduced by Alexander. The result was the January Uprising

The January Uprising was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at putting an end to Russian occupation of part of Poland and regaining independence. It began on 22 January 1863 and continued until the last i ...

of 1863–1864 that was suppressed after eighteen months of fighting. Hundreds of Poles were executed, and thousands were deported to Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. The price of suppression was Russian support for the unification of Germany

The unification of Germany (, ) was a process of building the first nation-state for Germans with federalism, federal features based on the concept of Lesser Germany (one without Habsburgs' multi-ethnic Austria or its German-speaking part). I ...

.

The martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

in Lithuania, introduced in 1863, lasted for the next 40 years. Native languages, Ukrainian, and Belarusian, were completely banned from printed texts, the Ems Ukase being an example. The authorities banned use of the Latin script for writing Lithuanian. The Polish language

Polish (, , or simply , ) is a West Slavic languages, West Slavic language of the Lechitic languages, Lechitic subgroup, within the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family, and is written in the Latin script. It is primarily spo ...

was banned in both oral and written form from all provinces except Congress Poland

Congress Poland or Congress Kingdom of Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It was established w ...

, where it was allowed in private conversations only.

Nikolay Milyutin was installed as governor and he decided that the best response to the January Uprising was to make reforms regarding the peasants. He devised a program which involved the emancipation of the peasantry at the expense of the nationalist landowners and the expulsion of Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

priests from schools. Emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure Economic, social and cultural rights, economic and social rights, civil and political rights, po ...

of the Polish peasantry from their serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

-like status took place in 1864, on more generous terms than the emancipation of Russian peasants in 1861.

Encouraging Finnish nationalism

In 1863, Alexander II re-convened theDiet of Finland

The Diet of Finland (Finnish language, Finnish ''Suomen maapäivät'', later ''valtiopäivät''; Swedish language, Swedish ''Finlands Lantdagar''), was the Diet (assembly), legislative assembly of the Grand Duchy of Finland from 1809 to 1906 ...

and initiated several reforms increasing Finland's autonomy within the Russian Empire, including establishment of its own currency, the Finnish markka

The markka (; ; currency symbol, sign: mk; ISO 4217, ISO code: FIM), also known as the Finnish mark, was the currency of Finland from 1860 until 28 February 2002, when it ceased to be legal tender. The markka was divided into 100 penny, pennies ...

. Liberation of business led to increased foreign investment and industrial development. Finland also got its first railways

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of land transport, next to roa ...

, separately established under Finnish administration. Finally, the elevation of Finnish from a language of the common people to a national language

'' ''

A national language is a language (or language variant, e.g. dialect) that has some connection— de facto or de jure—with a nation. The term is applied quite differently in various contexts. One or more languages spoken as first languag ...

equal to Swedish opened opportunities for a larger proportion of Finnish society. Alexander II is still regarded as "The Good Tsar" in Finland.

These reforms could be seen as results of a genuine belief that reforms were easier to test in an underpopulated, homogeneous country than in the whole of Russia. They may also be seen as a reward for the loyalty of its relatively western-oriented population during the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

and during the Polish uprising. Encouraging Finnish nationalism and language can also be seen as an attempt to dilute ties with Sweden.

Foreign affairs

During the Crimean WarAustria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

maintained a policy of hostile neutrality towards Russia, and, while not going to war, was supportive of the Anglo-French coalition. Having abandoned its alliance with Russia, Austria was diplomatically isolated following the war, which contributed to Russia's non-intervention in the 1859 Franco-Austrian War, which meant the end of Austrian influence in Italy; and in the 1866 Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War (German: ''Preußisch-Österreichischer Krieg''), also known by many other names,Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Second War of Unification, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), ''Deutsc ...

, with the loss of its influence in most German-speaking lands.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

(1861–1865), Russia supported the Union, largely due to the view that the U.S. served as a counterbalance to their geopolitical rival, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

. In 1863, the Russian Navy

The Russian Navy is the Navy, naval arm of the Russian Armed Forces. It has existed in various forms since 1696. Its present iteration was formed in January 1992 when it succeeded the Navy of the Commonwealth of Independent States (which had i ...

's Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originatin ...

and Pacific fleets wintered in the American ports of New York and San Francisco, respectively.

The Treaty of Paris of 1856 stood until 1871, when Prussia defeated France in the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

. During his reign, Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

, eager for the support of the United Kingdom, had opposed Russia over the Eastern Question. France abandoned its opposition to Russia after the establishment of the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

. Encouraged by the new attitude of French diplomacy and supported by the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

, Russia renounced the Black Sea clauses of the Paris treaty agreed to in 1856. As the United Kingdom with Austria could not enforce the clauses, Russia once again established a fleet in the Black Sea. France, after the Franco-Prussian War and the loss of Alsace–Lorraine

Alsace–Lorraine (German language, German: ''Elsaß–Lothringen''), officially the Imperial Territory of Alsace–Lorraine (), was a territory of the German Empire, located in modern-day France. It was established in 1871 by the German Empire ...

, was fervently hostile to Germany and maintained friendly relations with Russia.

In the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

The Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) was a conflict between the Ottoman Empire and a coalition led by the Russian Empire which included United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, Romania, Principality of Serbia, Serbia, and Principality of ...

the states of Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

, and Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

gained international recognition of their independence while Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

and Eastern Rumelia achieved their autonomy from direct Ottoman rule. Russia took over Southern Bessarabia, lost in 1856.

End of the Caucasian War

TheRusso-Circassian War

The Russo-Circassian War, also known as the Russian invasion of Circassia, was the 101-year-long invasion of Circassia by the Russian Empire. The conflict started in 1763 ( O.S.) with Russia assuming authority in Circassia, followed by Circa ...

(1763–1864) concluded as a Russian victory during Alexander II's rule. Just before the conclusion of the war the Russian Army, under the emperor's order, implemented the mass-killings and extermination of Circassian "mountaineers" in the Circassian genocide, which would be often referred to as "cleansing" and "genocide" in several historic dialogues.

In 1857, Dmitry Milyutin first published the idea of mass expulsions of Circassian natives.King, Charles. ''The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus''. p. 94. "In a policy memorandum in of 1857, Dmitri Milyutin, chief-of-staff to Bariatinskii, summarized the new thinking on dealing with the northwestern highlanders. The idea, Milyutin argued, was not to clear the highlands and coastal areas of Circassians so that these regions could be settled by productive farmers ... utRather, eliminating the Circassians was to be an end in itself – to cleanse the land of hostile elements. Tsar Alexander II

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland fro ...

formally approved the resettlement plan ... Milyutin, who would eventually become minister of war, was to see his plans realized in the early 1860s". Milyutin argued that the goal was not to simply move them so that their land could be settled by productive farmers, but rather that "eliminating the Circassians was to be an end in itself – to cleanse the land of hostile elements".. "In his memoirs Milutin Milutin () is a Serbian masculine given name of Slavic origin. The name may refer to:

*Stephen Uroš II Milutin of Serbia (1253–1321), king of Serbia

* Milutin Bojić (1892–1917), poet

* Milutin Ivković (1906–1943), footballer

*Milutin Milan ...

, who proposed deporting Circassians from the mountains as early as 1857, recalls: "the plan of action decided upon for 1860 was to cleanse [] the mountain zone of its indigenous population". Tsar Alexander II endorsed the plans. A large portion of indigenous Islam in Russia, Muslim peoples of the region were ethnically cleansed from their homeland at the end of the Russo-Circassian War

The Russo-Circassian War, also known as the Russian invasion of Circassia, was the 101-year-long invasion of Circassia by the Russian Empire. The conflict started in 1763 ( O.S.) with Russia assuming authority in Circassia, followed by Circa ...

by Russia. A large deportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people by a state from its sovereign territory. The actual definition changes depending on the place and context, and it also changes over time. A person who has been deported or is under sen ...

operation was launched against the remaining population before the end of the war in 1864 and it was mostly completed by 1867. Only a small percentage accepted surrender and resettlement within the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

. The remaining Circassian populations who refused to surrender were thus variously dispersed, resettled, or killed ''en masse''.

Liberation of Bulgaria

In April 1876, the Bulgarian population in the Balkans rebelled against Ottoman rule. The Ottoman authorities suppressed the April Uprising, causing a general outcry throughout Europe. Some of the most prominent intellectuals and politicians on the Continent, most notablyVictor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

and William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he was Prime Minister ...

, sought to raise awareness about the atrocities that the Turks imposed on the Bulgarian population. To solve this new crisis in the "Eastern question" a Constantinople Conference was convened by the Great Powers in Constantinople at the end of the year. The participants in the Conference failed to reach a final agreement.

After the failure of the Constantinople Conference, at the beginning of 1877, Emperor Alexander II started diplomatic preparations with the other Great Powers to secure their neutrality in case of a war between Russia and the Ottomans. Alexander II considered such agreements paramount in avoiding the possibility of causing his country a disaster similar to the Crimean War.

The Russian Emperor succeeded in his diplomatic endeavors. Having secured agreement as to non-involvement by the other Great Powers, on 17 April 1877 Russia declared war upon the Ottoman Empire. The Russians, helped by the Romanian Army under its supreme commander King Carol I (then Prince of Romania), who sought to obtain Romanian independence from the Ottomans as well, were successful against the Turks and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 ended with the signing of the preliminary peace Treaty of San Stefano on . The treaty and the subsequent

The Russian Emperor succeeded in his diplomatic endeavors. Having secured agreement as to non-involvement by the other Great Powers, on 17 April 1877 Russia declared war upon the Ottoman Empire. The Russians, helped by the Romanian Army under its supreme commander King Carol I (then Prince of Romania), who sought to obtain Romanian independence from the Ottomans as well, were successful against the Turks and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 ended with the signing of the preliminary peace Treaty of San Stefano on . The treaty and the subsequent Congress of Berlin

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the Russian Empire on the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878), which had ended the Rus ...

(June–July 1878) secured the emergence of an independent Bulgarian state for the first time since 1396, and Bulgarian parliamentarians elected the tsar's nephew, Prince Alexander of Battenberg, as the Bulgarians' first ruler.

For his social reforms in Russia and his role in the liberation of Bulgaria, Alexander II became known in Bulgaria as the "Tsar-Liberator of Russians and Bulgarians". A monument to Alexander II was erected in 1907 in Sofia in the "National Assembly" square, opposite to the Parliament building. The monument underwent a complete reconstruction in 2012, funded by the Sofia Municipality and some Russian foundations. The inscription on the monument reads in Old-Bulgarian style: "To the Tsar-Liberator from grateful Bulgaria". There is a museum dedicated to Alexander in the Bulgarian city of Pleven.

Assassination attempts

In April 1866, there was an attempt on the emperor's life in St. Petersburg by Dmitry Karakozov. To commemorate his narrow escape from death (which he himself referred to only as "the event of 4 April 1866"), a number of churches and chapels were built in many Russian cities. Viktor Hartmann, a Russian architect, even sketched a design of a monumental gate (which was never built) to commemorate the event.Modest Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky (; ; ; – ) was a Russian composer, one of the group known as "The Five (composers), The Five." He was an innovator of Music of Russia, Russian music in the Romantic music, Romantic period and strove to achieve a ...

later wrote his piano suite '' Pictures at an Exhibition'', the last movement of which, "The Great Gate of Kiev", is based on Hartmann's sketches.

During the 1867 World's Fair in Paris, Polish immigrant Antoni Berezowski attacked the carriage containing Alexander, his two sons and Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

. His self-modified double-barreled pistol misfired and struck the horse of an escorting cavalryman.

On the morning of 20 April 1879, Alexander was briskly walking towards the Square of the Guards Staff and faced Alexander Soloviev, a 33-year-old former student. Having seen a menacing revolver in his hands, the Emperor fled in a zigzag pattern. Soloviev fired five times but missed; he was sentenced to death and hanged on 28 May.

The student acted on his own, but other revolutionaries were keen to murder Alexander. In December 1879, the ''Narodnaya Volya

Narodnaya Volya () was a late 19th-century revolutionary socialist political organization operating in the Russian Empire, which conducted assassinations of government officials in an attempt to overthrow the autocratic Tsarist system. The org ...

'' (People's Will), a radical revolutionary group which hoped to ignite a social revolution

Social revolutions are sudden changes in the structure and nature of society. These revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed society, economy, culture, philosophy, and technology along with but more than just the political system ...

, organised an explosion on the railway from Livadia to Moscow, but they missed the emperor's train.

On the evening of 5 February 1880, Stephan Khalturin, also from ''Narodnaya Volya'', set off a timed charge under the dining room of the Winter Palace

The Winter Palace is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the House of Romanov, previous emperors, from 1732 to 1917. The palace and its precincts now house the Hermitage Museum. The floor area is 233,345 square ...

, right in the resting room of the guards a story below, killing 11 people and wounding 30 others. ''The New York Times'' (4 March 1880) reported "the dynamite used was enclosed in an iron box, and exploded by a system of clockwork used by the man Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

in Bremen some years ago." However, dinner had been delayed by the late arrival of the tsar's nephew, the Prince of Bulgaria, so the tsar and his family were not in the dining room at the time of the explosion and were unharmed.

Assassination

After the last assassination attempt in February 1880, Count Loris-Melikov was appointed the head of the Supreme Executive Commission and given extraordinary powers to fight the revolutionaries. Loris-Melikov's proposals called for some form of parliamentary body, and the Emperor seemed to agree; these plans were never realized. On , Alexander was assassinated inSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

.

As he was known to do every Sunday for many years, the emperor went to the Mikhailovsky Manège for the military roll call. He travelled both to and from the ''Manège'' in a closed carriage accompanied by five Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

and Frank (Franciszek) Joseph Jackowski, a Polish noble, with a sixth Cossack sitting on the coachman's left. The emperor's carriage was followed by two sleighs carrying, among others, the chief of police and the chief of the emperor's guards. The route, as always, was via the Catherine Canal and over the Pevchesky Bridge.

The street was flanked by narrow pavements for the public. A young member of the ''Narodnaya Volya

Narodnaya Volya () was a late 19th-century revolutionary socialist political organization operating in the Russian Empire, which conducted assassinations of government officials in an attempt to overthrow the autocratic Tsarist system. The org ...

'' ("People's Will") movement, Nikolai Rysakov, was carrying a small white package wrapped in a handkerchief. He later said of his attempt to kill the Tsar:

The explosion, while killing one of the Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

and seriously wounding the driver and people on the sidewalk, had only damaged the bulletproof carriage, a gift from Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

of France. The emperor emerged shaken but unhurt. Rysakov was captured almost immediately. Police Chief Dvorzhitzky heard Rysakov shout out to someone else in the gathering crowd. Dvorzhitzky offered to drive the Tsar back to the Palace in his sleigh. The Tsar agreed, but he decided to first see the culprit, and to survey the damage. He expressed solicitude for the victims. To the anxious inquires of his entourage, Alexander replied, "Thank God, I'm untouched".

Nevertheless, a second young member of the ''Narodnaya Volya'', Ignacy Hryniewiecki, standing by the canal fence, raised both arms and threw something at the emperor's feet. He was alleged to have shouted, "It is too early to thank God". Dvorzhitzky was later to write:

Later, it was learnt there was a third bomber in the crowd. Ivan Emelyanov stood ready, clutching a briefcase containing a bomb that was to be used if the other two bombers failed.

Alexander was carried by sleigh to the Winter Palace

The Winter Palace is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the House of Romanov, previous emperors, from 1732 to 1917. The palace and its precincts now house the Hermitage Museum. The floor area is 233,345 square ...

to his study where almost the same day twenty years earlier, he had signed the Emancipation Edict freeing the serfs. Alexander was bleeding to death, with his legs torn away, his stomach ripped open, and his face mutilated. Members of the Romanov family came rushing to the scene.

The dying emperor was given Communion and

The dying emperor was given Communion and Last Rites

The last rites, also known as the Commendation of the Dying, are the last prayers and ministrations given to an individual of Christian faith, when possible, shortly before death. The Commendation of the Dying is practiced in liturgical Chri ...

. When the attending physician, Sergey Botkin, was asked how long it would be, he replied, "Up to fifteen minutes." At 3:30 that day, the standard of Alexander II (his personal flag) was lowered for the last time.

Aftermath

Alexander II's death caused a great setback for the reform movement. One of his last acts was the approval of Mikhail Loris-Melikov's constitutional reforms. Though the reforms were conservative in practice, their significance lay in the value Alexander II attributed to them: "I have given my approval, but I do not hide from myself the fact that it is the first step towards a constitution." In a matter of 48 hours, Alexander II planned to release these plans to the Russian people. Instead, following his succession, Alexander III, under the advice of Konstantin Pobedonostsev, chose to abandon these reforms and went on to pursue a policy of greater autocratic power. The assassination triggered major suppression of civil liberties in Russia, andpolice brutality

Police brutality is the excessive and unwarranted use of force by law enforcement against an individual or Public order policing, a group. It is an extreme form of police misconduct and is a civil rights violation. Police brutality includes, b ...

burst back in full force after experiencing some restraint under the reign of Alexander II, whose death was witnessed first-hand by his son, Alexander III, and his grandson, Nicholas II, both future emperors who vowed not to have the same fate befall them. Both of them used the Okhrana

The Department for the Protection of Public Safety and Order (), usually called the Guard Department () and commonly abbreviated in modern English sources as the Okhrana ( rus , Охрана, p=ɐˈxranə, a=Ru-охрана.ogg, t= The Guard) w ...

to arrest protestors and uproot suspected rebel groups, creating further suppression of personal freedom for the Russian people. A series of anti-Jewish pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s and antisemitic legislation, the May Laws

Temporary regulations regarding the Jews (also known as May Laws) were residency and business restrictions on Jews in the Russian Empire, proposed by minister Nikolay Pavlovich Ignatyev and enacted by Tsar Alexander III on . Originally, intende ...

, were yet another result.

Finally, the tsar's assassination also inspired anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or hierarchy, primarily targeting the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state w ...

to advocate "' propaganda by deed'—the use of a spectacular act of violence to incite revolution."

In 1881, the Alexander Church, designed by Theodor Decker and named after Alexander II, was completed in Tampere

Tampere is a city in Finland and the regional capital of Pirkanmaa. It is located in the Finnish Lakeland. The population of Tampere is approximately , while the metropolitan area has a population of approximately . It is the most populous mu ...

. Also, with construction starting in 1883, the Church of the Savior on Blood was built on the site of Alexander's assassination and dedicated in his memory.

Marriages and children

First marriage

Nicholas I of Russia

Nicholas I, group=pron (Russian language, Russian: Николай I Павлович; – ) was Emperor of Russia, List of rulers of Partitioned Poland#Kings of the Kingdom of Poland, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 18 ...

suggested Princess Alexandrine of Baden as a suitable choice, but he was prepared to allow Alexander to choose his own bride, as long as she was not Roman Catholic or a commoner.John Van der Kiste, "The Romanovs 1818–1959," p. 11 Alexander stayed for three days with the maiden Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

. The two got along well, but there was no question of marriage between two major monarchs.

In Germany, Alexander made an unplanned stop in Darmstadt. He was reluctant to spend "a possibly dull evening" with their host Louis II, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine, but he agreed to do so because Vasily Zhukovsky insisted that his entourage was exhausted and needed a rest. During dinner, he met and was charmed by Princess Marie, the 14-year-old daughter of Louis II. He was so smitten that he declared that he would rather abandon the succession than not marry her.John Van der Kiste, "The Romanovs 1818–1959," p. 12 He wrote to his father: "I liked her terribly at first sight. If you permit it, dear father, I will come back to Darmstadt after England." When he left Darmstadt, she gave him a locket that contained a piece of her hair.

Alexander's parents initially did not support his decision to marry Princess Marie of Hesse. There were troubling rumors about her paternity. Although she was the legal daughter of Louis II, there were rumors that Marie was the biological daughter of her mother's lover, Baron August von Senarclens de Grancy. Alexander's parents worried that Marie could have inherited her mother's consumption. Alexander's mother

A mother is the female parent of a child. A woman may be considered a mother by virtue of having given birth, by raising a child who may or may not be her biological offspring, or by supplying her ovum for fertilisation in the case of ges ...

considered the Hesse family grossly inferior to the Hohenzollerns and Romanovs.

In April 1840, Alexander's engagement to Princess Marie was officially announced.John Van der Kiste, "The Romanovs 1818–1959," p. 13 In August, the 16-year-old Marie left Darmstadt for Russia. In December, she was received into the Orthodox Church and received the names ''Maria Alexandrovna''.

On 16 April 1841, aged 23, Tsesarevitch Alexander married Marie in St. Petersburg.

The marriage produced six sons and two daughters:

* Grand Duchess Alexandra Alexandrovna of Russia (30 August 1842 – 10 July 1849), nicknamed Lina, died of infant meningitis in St. Petersburg at the age of six

* Nicholas Alexandrovich, Tsesarevich of Russia (20 September 1843 – 24 April 1865), engaged to Princess Dagmar of Denmark

* Emperor Alexander III (10 March 1845 – 1 November 1894) he married Princess Dagmar of Denmark on 9 November 1866. They had six children.

* Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia (22 April 1847 – 17 February 1909) he married Duchess Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin on 28 August 1874. They had five children.

* Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich (14 January 1850 – 14 November 1908) he married Alexandra Zhukovskaya in 1870. They had one son.

* Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia

Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia (; – 22 October 1920) was the sixth child and only surviving daughter of Alexander II of Russia and Marie of Hesse and by Rhine; she was Duchess of Edinburgh and later Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and G ...

(17 October 1853 – 24 October 1920) she married Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Alfred (Alfred Ernest Albert; 6 August 184430 July 1900) was sovereign Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha from 22 August 1893 until his death in 1900. He was the second son and fourth child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He was known as the Du ...

on 23 January 1874. They had six children.

* Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia (11 May 1857 – 17 February 1905) he married Princess Elisabeth of Hesse and by Rhine on 15 June 1884. They had no children.

* Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia (3 October 1860 – 24 January 1919) he married Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark on 17 June 1889. They had two children. He remarried Olga Karnovich on 10 October 1902. They had three children.

Alexander particularly placed hope in his eldest son, Tsesarevich Nicholas. In 1864, Alexander II found Nicholas a bride, Princess Dagmar of Denmark, second daughter of King Christian IX of Denmark