Cyprian Norwid on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

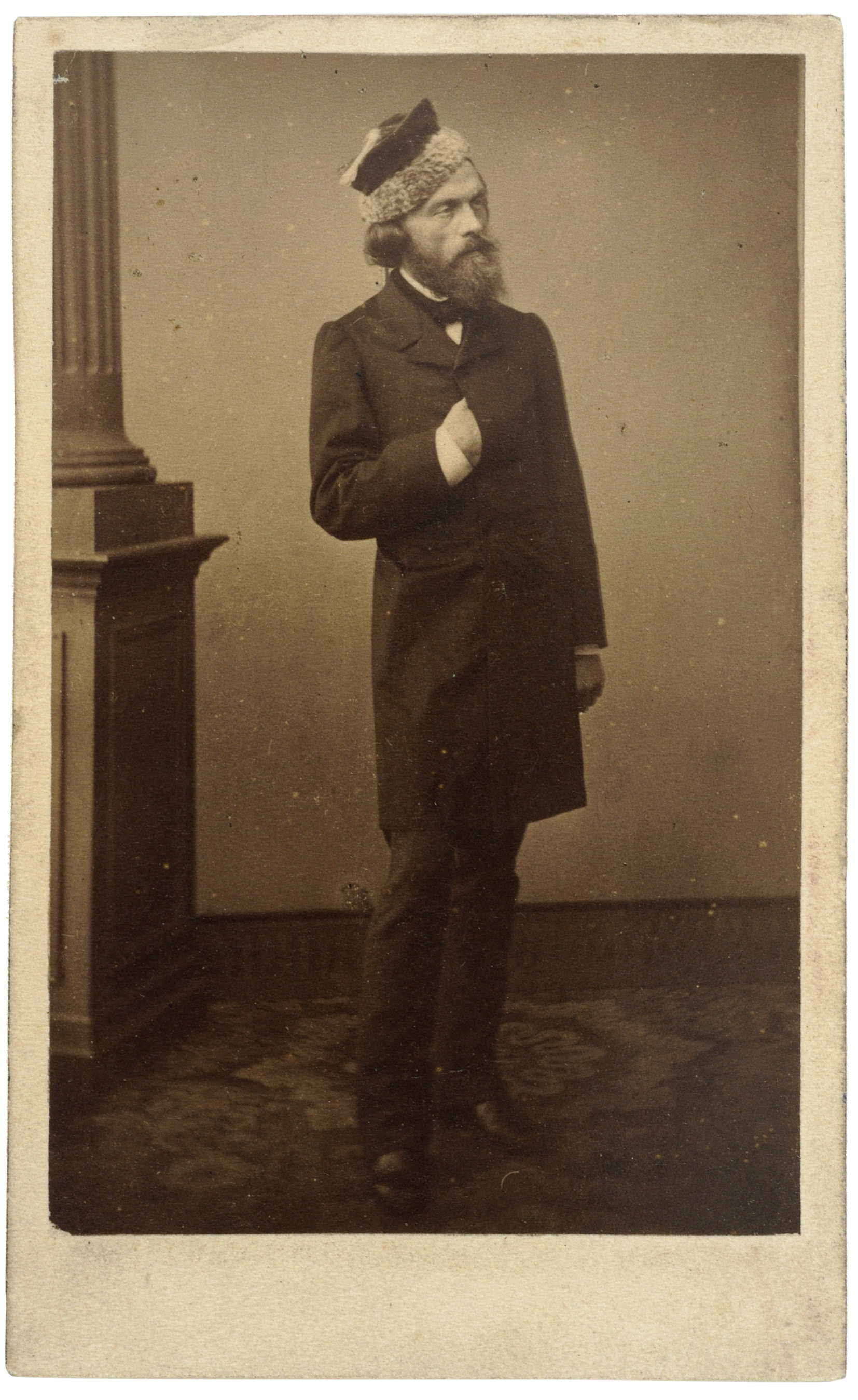

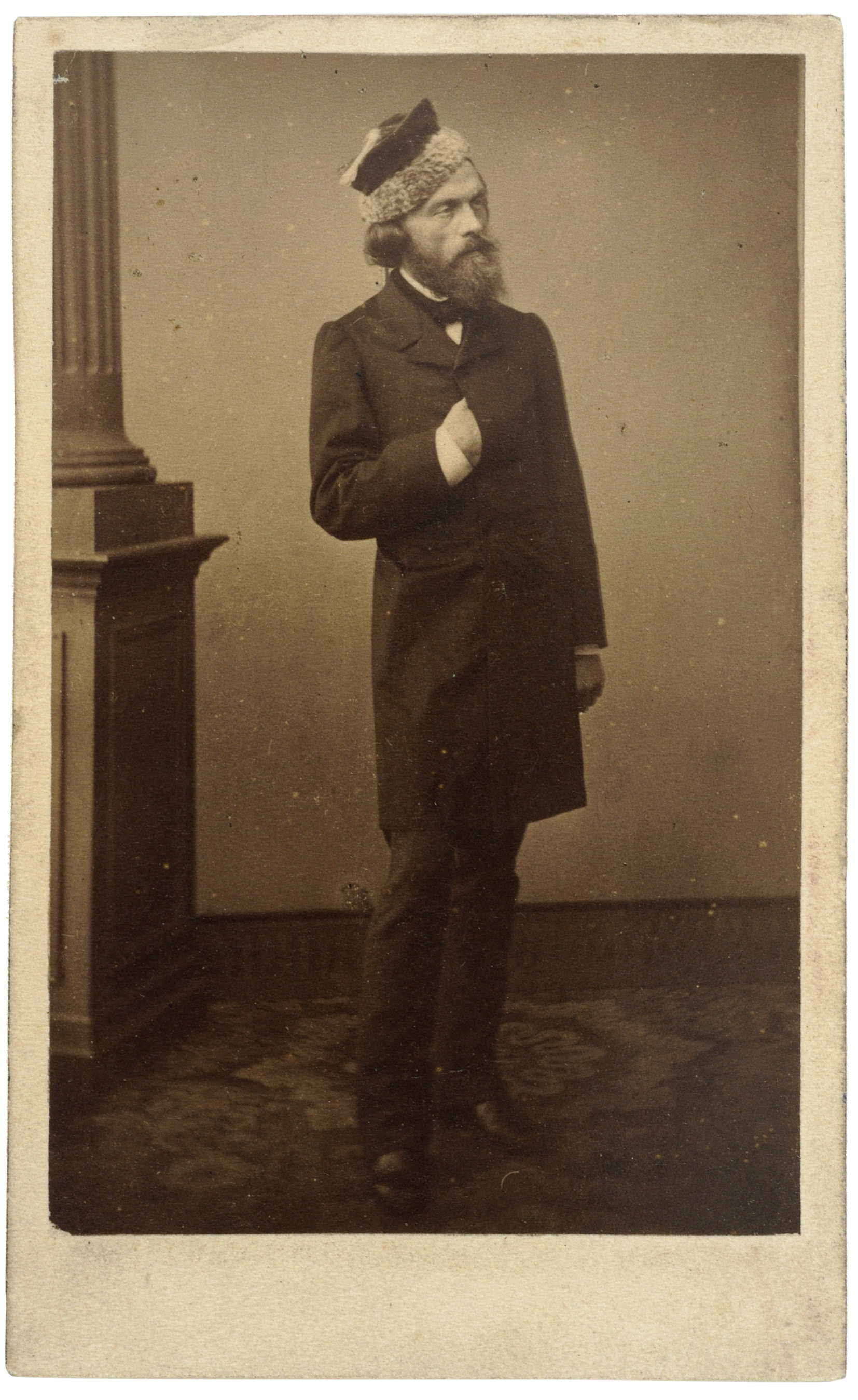

Cyprian Kamil Norwid (; – 23 May 1883) was a Polish

In 1842 Norwid received inheritance funds as well as a private scholarship to study sculpture and left Poland, never to return. First he went to

In 1842 Norwid received inheritance funds as well as a private scholarship to study sculpture and left Poland, never to return. First he went to

In 1866, the poet finished his work on '' Vade-mecum'', a vast anthology of verse. However, despite his greatest efforts it could not be published until decades later. One of the reasons for this included Prince

In 1866, the poet finished his work on '' Vade-mecum'', a vast anthology of verse. However, despite his greatest efforts it could not be published until decades later. One of the reasons for this included Prince

Critics and literary historians eventually concluded that during his life, Norwid was rejected by his contemporaries as his works were too unique. His style increasingly departing from then-prevailing forms and themes found in romanticism and

Critics and literary historians eventually concluded that during his life, Norwid was rejected by his contemporaries as his works were too unique. His style increasingly departing from then-prevailing forms and themes found in romanticism and

Norwid authored numerous works, from poems, both epic and short, to plays, short stories, essays and letters. During his lifetime, according to Miłosz and Gömöri, he published only one large volume of poetry (in 1862) (although Borchardt mentions another volume from 1866). Borchardt considers his major works to be ''Vade-mecum'', ''Promethidion'' and ''Ad leones!''. Miłosz acknowledged ''Vade-mecum'' as Norwid's most influential work, but also praised the earlier '' Bema pamięci rapsod żałobny'' as one of his most famous poems.

Norwid's most extensive work,''Vade-mecum'', written between 1858 and 1865, was first published a century after his death. Some of Norwid's works have been translated into English by Walter Whipple and

Norwid authored numerous works, from poems, both epic and short, to plays, short stories, essays and letters. During his lifetime, according to Miłosz and Gömöri, he published only one large volume of poetry (in 1862) (although Borchardt mentions another volume from 1866). Borchardt considers his major works to be ''Vade-mecum'', ''Promethidion'' and ''Ad leones!''. Miłosz acknowledged ''Vade-mecum'' as Norwid's most influential work, but also praised the earlier '' Bema pamięci rapsod żałobny'' as one of his most famous poems.

Norwid's most extensive work,''Vade-mecum'', written between 1858 and 1865, was first published a century after his death. Some of Norwid's works have been translated into English by Walter Whipple and

Speech about Norwid made by Pope John Paul II to the representatives of the Institute of Polish National Patrimony

Biography links

Profile of Cyprian Norwid

at Culture.pl

Why You Should Read Norwid, Poland's Starving Time Traveller

from Culture.pl

Repository of translated poems

Cyprian Kamil Norwid

collected works (Polish) * * *

' *

' *

' *

' *

' {{DEFAULTSORT:Norwid, Cyprian Kamil 1821 births 1883 deaths People from Wyszków County 19th-century Polish painters 19th-century Polish male artists 19th-century Roman Catholics Polish male sculptors Polish male dramatists and playwrights Polish Roman Catholic writers Activists of the Great Emigration 19th-century Polish sculptors 19th-century Polish poets 19th-century Polish dramatists and playwrights Polish male poets 19th-century Polish male writers 19th-century Polish philosophers Polish male painters

poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator (thought, thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral t ...

, dramatist

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays, which are a form of drama that primarily consists of dialogue between characters and is intended for theatrical performance rather than just

reading. Ben Jonson coined the term "playwri ...

, painter

Painting is a Visual arts, visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or "Support (art), support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with ...

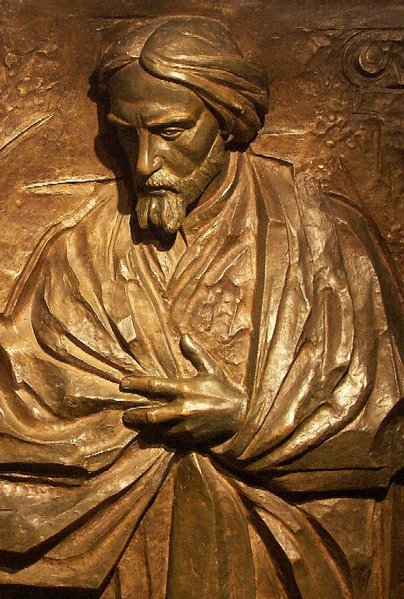

, sculptor

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

, and philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

. He is now considered one of the four most important Polish Romantic poets, though scholars still debate whether he is more aptly described as a late romantic or an early modernist

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

.

Norwid led a tragic, often poverty-stricken life. He experienced mounting health problems, unrequited love, harsh critical reviews, and increasing social isolation. For most of his life he lived abroad, having left Polish lands in his twenties. Having briefly travelled across Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

in his youth, and briefly travelling to United States, where he worked as an illustrator, he lived chiefly in Paris, where he eventually died.

Considered a "rising star" in his youth, Norwid's original, nonconformist style was not appreciated in his lifetime. Partly due to this, he was excluded from high society. His work was rediscovered and appreciated only after his death by the Young Poland movement of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Today his most influential work is considered to be '' Vade-mecum'', a vast anthology of verse he finished in 1866. Much of his work, including ''Vade-mecum'', remained unpublished during his lifetime.

Life

Youth

Cyprian Norwid was born on 24 September 1821 into a family of Polish–Lithuanian minor nobility bearing the Topór coat of arms, in theMasovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( ) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the largest city and Płock being the capital of the region . Throughout the ...

n village of Laskowo- Głuchy near Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

, His father was a minor government official. One of his maternal ancestors was the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( (); (); () 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobieski was educated at the Jagiellonian University and toured Eur ...

.

Cyprian Norwid and his brother were orphaned early. His mother died when Cyprian was four years old, and in 1835 his father also died: Norwid was 14 at the time. For most of their childhood, Cyprian and his brother were educated at Warsaw schools. In 1836 Norwid interrupted his schooling (not having completed the fifth grade) and entered a private school of painting, studying under Aleksander Kokular and . His incomplete formal education forced him to become an autodidact

Autodidacticism (also autodidactism) or self-education (also self-learning, self-study and self-teaching) is the practice of education without the guidance of schoolmasters (i.e., teachers, professors, institutions).

Overview

Autodi ...

, and eventually he learned a dozen languages.

Norwid's first foray into the literary sphere occurred in the periodical '' Piśmiennictwo Krajowe'', which published his first poem, '' Mój ostatni sonet'' (''My Last Sonnet''), in 1840s issue 8. That year he published ten poems and one short story. His early poems were well received by critics and he became a welcome guest at the literary salons of Warsaw; his personality of that time is described as that of a "dandy" and a "rising star" of the young generation of Polish poets. In 1841-1842 he travelled through the Congress Poland

Congress Poland or Congress Kingdom of Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It was established w ...

with .

Europe

In 1842 Norwid received inheritance funds as well as a private scholarship to study sculpture and left Poland, never to return. First he went to

In 1842 Norwid received inheritance funds as well as a private scholarship to study sculpture and left Poland, never to return. First he went to Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

in Germany. He later also visited Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

and Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

in Italy; in Florence he signed up for a course in sculpture at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze

The Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze () is an instructional art academy in Florence, in Tuscany, in central Italy.

It was founded by Cosimo I de' Medici in 1563, under the influence of Giorgio Vasari. Michelangelo, Benvenuto Cellini and ...

. His visit to Verona

Verona ( ; ; or ) is a city on the Adige, River Adige in Veneto, Italy, with 255,131 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region, and is the largest city Comune, municipality in the region and in Northeast Italy, nor ...

resulted in a well-received poem ' (''In Verona'') published several years later. After he settled in Rome in 1844, where for several years he became a regular at Caffè Greco, his fiancée Kamila broke off their engagement. Later he met Maria Kalergis, née Nesselrode; they became acquaintances, but his courtship of her, and later, of her lady-in-waiting, Maria Trebicka, ended in failure. The poet then travelled to Berlin, where he participated in university lectures and meetings with local '' Polonia''. It was a time when Norwid made many new social, artistic and political contacts. At that time he also lost his Russian passport, and after he refused to join the Russian diplomatic service, the Russian authorities confiscated his estate. He was also arrested for trying to cross back to Russia without his passport, and his short stay in Berlin prison resulted in partial deafness

Deafness has varying definitions in cultural and medical contexts. In medical contexts, the meaning of deafness is hearing loss that precludes a person from understanding spoken language, an audiological condition. In this context it is writte ...

. After being forced to leave Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

in 1846, Norwid went to Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

. During the European Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

, he stayed in Rome, where he met fellow Polish intellectuals Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. He also largely influenced Ukra ...

and Zygmunt Krasiński.

During 1849–1852, Norwid lived in Paris, where he met fellow Poles Frédéric Chopin

Frédéric François Chopin (born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin; 1 March 181017 October 1849) was a Polish composer and virtuoso pianist of the Romantic period who wrote primarily for Piano solo, solo piano. He has maintained worldwide renown ...

and Juliusz Słowacki, as well as other emigree artists such as Russians Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev ( ; rus, links=no, Иван Сергеевич ТургеневIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; – ) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, poe ...

and Alexander Herzen

Alexander Ivanovich Herzen (; ) was a Russian writer and thinker known as the precursor of Russian socialism and one of the main precursors of agrarian populism (being an ideological ancestor of the Narodniki, Socialist-Revolutionaries, Trudo ...

, and other intellectuals such as Jules Michelet

Jules Michelet (; 21 August 1798 – 9 February 1874) was a French historian and writer. He is best known for his multivolume work ''Histoire de France'' (History of France). Michelet was influenced by Giambattista Vico; he admired Vico's emphas ...

(many at Emma Herwegh's salon). Financial hardship, unrequited love, political misunderstandings, and a negative critical reception of his works put Norwid in a dire situation. He lived in poverty, sometimes forced to work as a simple manual laborer. He also suffered from progressive blindness

Visual or vision impairment (VI or VIP) is the partial or total inability of visual perception. In the absence of treatment such as corrective eyewear, assistive devices, and medical treatment, visual impairment may cause the individual difficul ...

and deafness

Deafness has varying definitions in cultural and medical contexts. In medical contexts, the meaning of deafness is hearing loss that precludes a person from understanding spoken language, an audiological condition. In this context it is writte ...

, but still managed to publish some content in the Polish-language Parisian publication ''Goniec polski'' and similar venues. 1849 saw several of his poems published, those included among others his ' (''Social Song''). Some of his other notable works from that period include the drama

Drama is the specific Mode (literature), mode of fiction Mimesis, represented in performance: a Play (theatre), play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on Radio drama, radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a g ...

' and the philosophical poem-treaty about the nature of art, ', both published in 1851. ''Promethidion'', a long treatise on aesthetics

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and taste (sociology), taste, which in a broad sense incorporates the philosophy of art.Slater, B. H.Aesthetics ''Internet Encyclopedia of Ph ...

in verse, has been called "the first important piece of Norwid's writing". It was, however, not well received by contemporary critics. That year also saw him finishing the manuscripts for the dramas ' and ' and the poem ''Bema pamięci żałobny rapsod'' ('' A Funeral Rhapsody in Memory of General Bem'').

United States

Norwid decided to emigrate to the United States in the Fall of 1852, receiving some sponsorship from Wladysław Zamoyski, a Polish nobleman and philanthropist. On 11 February 1853, after a harrowing journey, he arrived inNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

aboard the '' Margaret Evans'', and he held a number of odd jobs there, including at a graphics firm. He was involved in the creation of the memorial album of the Crystal Palace Exhibition and the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations

An exhibition, in the most general sense, is an organized presentation and display of a selection of items. In practice, exhibitions usually occur within a cultural or educational setting such as a museum, art gallery, park, library, exhibit ...

. By autumn, he learned about the outbreak of the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

. This, as well as his disappointment with America, which he felt lacked "history", made him consider a return to Europe, and he wrote to Mickiewicz and Herzen, asking for their assistance.

Back in Paris

During April 1854, Norwid returned to Europe with Prince . He lived in England and with Krasiński's help he was finally able to return to Paris by December that year. Over the next few years Norwid was able to publish several works, such as the poem ' (''Quidam. A Story,'' 1857) and stories collected in ' (''Black Flowers'') and ' (''White Flowers''), published in ' in 1856–1857. He gave a well-received series of six lectures on Juliusz Słowacki in 1860, published the next year. 1862 saw the publication of some of his poems in an anthology ''Poezje'' (''Poems'') at Brockhaus inLeipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

. He took a very keen interest in the outbreak of the 1863 January Uprising

The January Uprising was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at putting an end to Russian occupation of part of Poland and regaining independence. It began on 22 January 1863 and continued until the last i ...

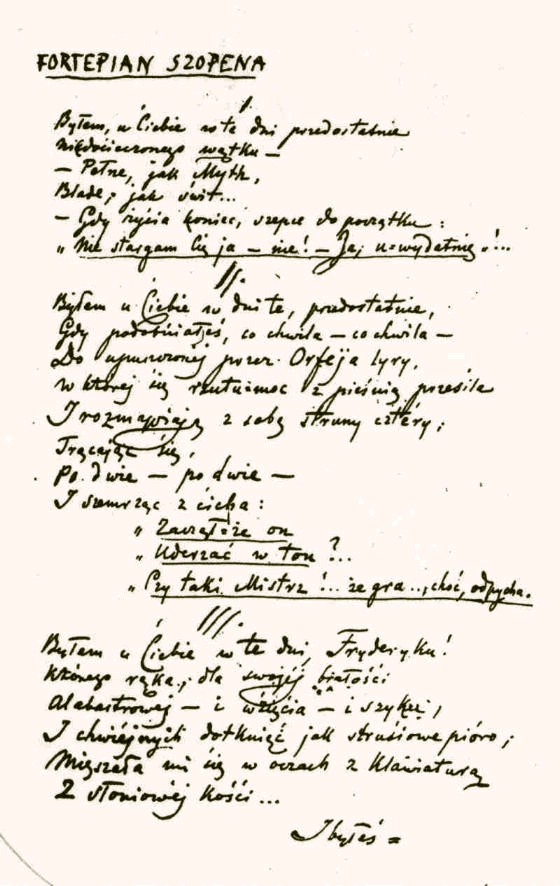

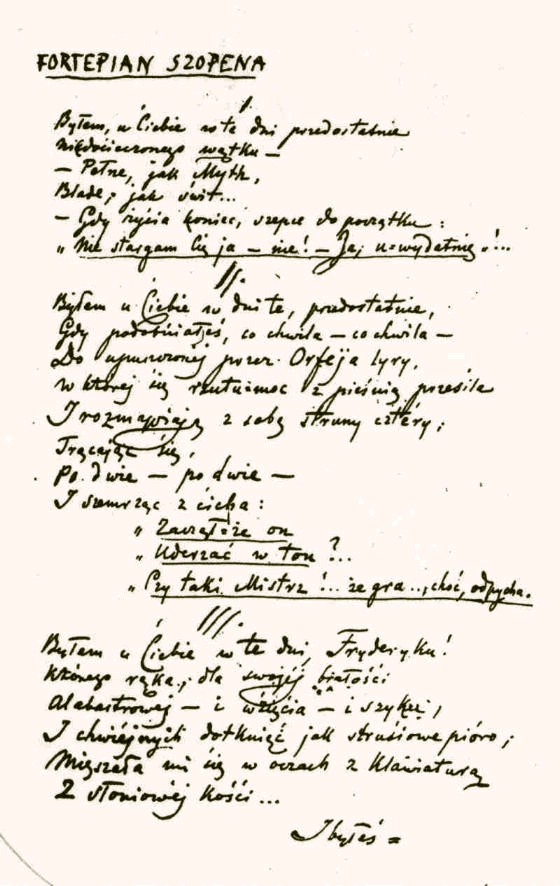

(a Polish–Lithuanian revolt against the Russian Empire). Although he could not participate personally due to his poor health, Norwid hoped to personally influence the outcome of the event by establishing a newspaper or magazine; that project however did not come to fruition. His 1865 ' (''Chopin's Piano'') is seen as one of his works reacting to the January Uprising. The poem's theme is the Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

troops' 1863 defenestration of Chopin's piano

A piano is a keyboard instrument that produces sound when its keys are depressed, activating an Action (music), action mechanism where hammers strike String (music), strings. Modern pianos have a row of 88 black and white keys, tuned to a c ...

from the music school Norwid attended in his youth.

Norwid continued writing, but most of his work met with little recognition. He grew to accept this, and even wrote in one his works that "the sons pass by this writing, but you, my distant grandchild, will read it... when I'll be no more" (', ''The Hands Were Swollen by Clapping...'', 1858).

In 1866, the poet finished his work on '' Vade-mecum'', a vast anthology of verse. However, despite his greatest efforts it could not be published until decades later. One of the reasons for this included Prince

In 1866, the poet finished his work on '' Vade-mecum'', a vast anthology of verse. However, despite his greatest efforts it could not be published until decades later. One of the reasons for this included Prince Władysław Czartoryski

Prince Władysław (Ladislaus) Czartoryski (3 July 1828 – 23 June 1894) was a Polish noble, political activist in exile, collector of art, and founder of the Czartoryski Museum in Kraków.

Early life

Czartoryski was born in Warsaw, Congres ...

failing to grant the poet the loan he had promised. In subsequent years, Norwid lived in extreme poverty and suffered from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. During the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

of 1870, many of his friends and patrons were distracted with the global events: Norwid experienced starvation, and his health further deteriorated. Material hardships did not stop him from writing: in 1869 he wrote ' (''A Poem About the Freedom of the Word''), a long treatise in verse about the history of words

A word is a basic element of language that carries meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible. Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its ...

, which was well received at that time. The next year he wrote ', a poem reflecting his views on Christian love, which Hungarian poet George Gömöri called Norwid's "most successful narrative poem". Those years also saw him write three more plays, comedies ' (''Actor. Comedy-drama'', 1867), ' (''Behind the Scenes'', 1865–1866), and ' (''The Ring of a Grand Lady'', 1872), which Gömöri praised as Norwid's "real genre within the theater". The latter play became Norwid's most frequently performed theater piece, although like many of his works, it gained recognition long after his death (published in print in 1933, and staged in 1936).

In 1877 his cousin, relocated Norwid to the (Œuvre de Saint Casimir) on the outskirts of Paris in Ivry. That location, run by Polish nuns, was home to many destitute Polish emigrants. There, Norwid was befriended by Teodor Jełowicki who also gave him material support. Some of his final works include a comedy play ' (''Pure Love at Sea Baths'', 1880), the philosophical treatesie ' (''Silence'', 1882), and novels ' (written c. 1881–83), ''Stygmat'' (''Stigmata'', 1881–82) and ''Tajemnica lorda Singelworth'' (''The Secret of Lord Singelworth'', 1883). Throughout his life, he also wrote many letters, over a thousand of which survived to be studied by scholars.

During the last months of his life, Norwid was weak and bed-ridden. He frequently wept and refused to speak with anyone. He died in the morning of 23 May 1883. Jełowicki and Kleczkjowski personally covered the burial costs, and Norwid's funeral was also attended by Franciszek Duchiński and . After 15 years the funds to maintain his grave dried out and his body was moved to a mass grave of Polish emigrants.

Themes and views

Norwid's early style could be classified as belonging within the romanticism tradition, but it soon evolved beyond it. Some scholars consider Norwid to represent lateromanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

, while others see him as an early modernist

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

. Polish literary critics, , Tamara Trojanowska and Joanna Niżyńska described Norwid as "a 'late child' and simultaneously a great critic of Romanticism" and "the first post-Romantic poet f Poland. Danuta Borchardt

Danuta is a Polish feminine given name. Its diminutive is Danusia.

Notable people named Danuta include:

*Danuta Bartoszek (born 1961), long-distance runner for Canada

* Danuta Bułkowska (born 1959), former Polish champion in high jumping

* Danut ...

who translated some of Norwid's poems to English wrote that "Norwid's work belongs to late Romanticism. However, he was so original that scholars cannot pigeonhole his work into any specific literary period". Czesław Miłosz

Czesław Miłosz ( , , ; 30 June 1911 – 14 August 2004) was a Polish Americans, Polish-American poet, prose writer, translator, and diplomat. He primarily wrote his poetry in Polish language, Polish. Regarded as one of the great poets of the ...

, a Polish poet and Nobel laureate, wrote that " orwidpreserved complete independence from the literary currents of the day". This could be seen in his short stories, which went against the common trend in the 19th century to write realistic prose and instead are more aptly described as "modern parable

A parable is a succinct, didactic story, in prose or verse, that illustrates one or more instructive lessons or principles. It differs from a fable in that fables employ animals, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature as characters, whe ...

s". Critics and literary historians eventually concluded that during his life, Norwid was rejected by his contemporaries as his works were too unique. His style increasingly departing from then-prevailing forms and themes found in romanticism and

Critics and literary historians eventually concluded that during his life, Norwid was rejected by his contemporaries as his works were too unique. His style increasingly departing from then-prevailing forms and themes found in romanticism and positivism

Positivism is a philosophical school that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positivemeaning '' a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. Gerber, ''Soci ...

, and the subjects of his works were also often not aligned with the political views of the emigre Poles. His style was criticized for "being obscure and overly cerebral" and having a "jarring syntax". Even today, a number of scholars refer to his works, in this context, as "dark", meaning "weird" or "difficult to understand".

While Norwid did not create neologisms

In linguistics, a neologism (; also known as a coinage) is any newly formed word, term, or phrase that has achieved popular or institutional recognition and is becoming accepted into mainstream language. Most definitively, a word can be considered ...

, he would change words creating new variations of existing language, and he also experimented with syntax and punctuation, for example through the use of hyphen

The hyphen is a punctuation mark used to join words and to separate syllables of a single word. The use of hyphens is called hyphenation.

The hyphen is sometimes confused with dashes (en dash , em dash and others), which are wider, or with t ...

ated words, which are uncommon in the Polish language. Much of his work is rhymed, although some is seen as a precursor to free verse

Free verse is an open form of poetry which does not use a prescribed or regular meter or rhyme and tends to follow the rhythm of natural or irregular speech. Free verse encompasses a large range of poetic form, and the distinction between free ...

that later became more common in Polish poetry. Miłosz noted that Norwid was "against aestheticism", and that he aimed to "break the monotony... of the syllabic pattern", purposefully making his verses "roughhewn".

While Norwid displays a Romantic admiration for heroes, he almost never addresses the concept of romantic love

Romance or romantic love is a feeling of love for, or a Interpersonal attraction, strong attraction towards another person, and the Courtship, courtship behaviors undertaken by an individual to express those overall feelings and resultant ...

. Norwid attempted to start new types of literary works, for example " high comedy" and "bloodless white tragedy". His works are considered to be deeply philosophical and utilitarian, and he rejected "art for art's sake". He is seen as a harsh critic of the Polish society as well as of mass culture

Popular culture (also called pop culture or mass culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as popular art pop_art.html" ;"title="f. pop art">f. pop artor mass art, somet ...

. His portrayal of women characters has been praised as more developed than that of many of his contemporaries, whose female characters were more one-dimensional. Borchardt summarized his ideas as "that of a man deeply distressed by and disappointed in mankind, yet hopeful of its eventual redemption". Miłosz pointed out that Norwid used irony (comparing his use of it to Jules Laforgue or T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist and playwright.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biography''. New York: Oxford University ...

), but it was "so hidden within symbols and parables" that it was often missed by most readers. He also argued that Norwid is "undoubtedly... the most 'intellectual' poet to ever write in Polish", although lack of audience has "permitted him to indulge in such a torturing of the language that some of his lines are hopelessely obscure".

Norwid's works featured more than purely Polish context, employing pan-European, Greco-Christian symbology. They also endorsed orthodox Christian, Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

views; in fact Gömöri argues that one of his major themes was "the state and future of Christian civilization". Miłosz similarly noted that Norwid did not reject civilization, although he was critical of some of its aspects; he saw history as a story of progress "to make martyrdom unnecessary on Earth". Historical references are common in Norwid's work, which Miłosz describes as affected by "intense historicism

Historicism is an approach to explaining the existence of phenomena, especially social and cultural practices (including ideas and beliefs), by studying the process or history by which they came about. The term is widely used in philosophy, ant ...

". Norwid's stay in America also made him a supporter of the abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

movement, and in 1859 he wrote two poems about John Brown ''Do obywatela Johna Brown'' (''To Citizen John Brown'') and ''John Brown''. Another recurring motif in his work was the importance of labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

, particularly in the context of artistic work, with his discussions of issues such as how artists should be compensated in the capitalistic society - although Miłosz noted that Norwid was not a socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

.

Norwid's work has also been treated as deeply philosophical. Miłosz also noted that some consider Norwid to be a philosopher more than an artist, and indeed Norwid has inspired, among others, philosophers such as Stanisław Brzozowski. Nonetheless, Miłosz disagrees with that notion, quoting Mieczysław Jastrun who wrote that Norwid was "first of all, an artist, but an artist for whom the most interesting material is thought, reflection, the cultural experience of mankind".

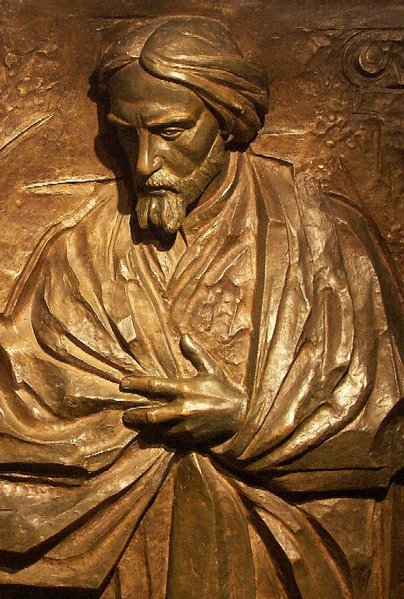

Legacy and commemoration

Following his death, many of Norwid's works were forgotten; it was not until the early 20th century, in the Young Poland period, that his finesse and style was appreciated. At that time, his work was discovered and popularised byZenon Przesmycki

Zenon Przesmycki (pen name ''Miriam''; Radzyń Podlaski, 22 December 1861 – 17 October 1944, Warsaw), was a Polish poet, translator and an art critic of the literary period of Młoda Polska, who studied law in Italy, France and England; in yea ...

, a Polish poet and literary critic who was a member of the Polish Academy of Literature. Przesmycki started republishing Norwid's works c. 1897, and created an enduring image of him, one of "the dramatic legend of the cursed poet".

Norwid's "Collected Works" (''Dzieła Zebrane'') were published in 1966 by , a Norwid biographer and commentator. The full iconic collection of Norwid's work was released during the period 1971–76 as ''Pisma Wszystkie'' ("Collected Works"). Comprising 11 volumes, it includes all of Norwid's poetry as well as his letters and reproductions of his artwork.

On 24 September 2001, 118 years after his death, an urn with soil from the collective grave where Norwid had been interred in Paris' Montmorency cemetery was buried in the "" at Wawel Cathedral

The Wawel Cathedral (), formally titled the Archcathedral Basilica of Stanislaus of Szczepanów, Saint Stanislaus and St. Wenceslas, Saint Wenceslaus, () is a Catholic cathedral situated on Wawel Hill in Kraków, Poland. Nearly 1000 years old, it ...

. There, Norwid's remains were placed next to those of fellow Polish poets Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki. During a mass held at the cathedral, the Archbishop of Kraków, cardinal Franciszek Macharski said that the doors of the crypt have opened "to receive the great poet, Cyprian Norwid, into Wawel's royal cathedral, for he was an equal of kings".

In 2021, on the 200th anniversary of Norwid's birth, the brothers Stephen

Stephen or Steven is an English given name, first name. It is particularly significant to Christianity, Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; he is w ...

and Timothy Quay produced a short film titled ''Vade-mecum'' about the poet's life and work in an attempt to promote his legacy among foreign audiences.

Norwid is often considered the fourth more important poet of the Polish romanticism, and called the Fourth of the Three Bards. In fact, some literary critics of the late 20th-century Poland were skeptical as to the value of Krasiński's work and considered Norwid to be the ''Third'' bard instead of ''Fourth''. Well known in Poland, and a part of Polish school's curricula, Norwid nonetheless remains obscure in English-speaking world. He has been praised as the best poet of the 19th century by Joseph Brodsky

Iosif Aleksandrovich Brodsky (; ; 24 May 1940 – 28 January 1996) was a Russian and American poet and essayist. Born in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) in the Soviet Union, Brodsky ran afoul of Soviet authorities and was expelled ("strongly ...

and Tomas Venclova. Miłosz notes he has become recognized as a "precusor of modern Polish poetry".

The life and work of Norwid have been subject to a number of scholarly treatments. Those include the English-language collection of essays about him, published after a 1983 conference held to commemorate century since his death (''Cyprian Norwid (1821-1883): Poet - Thinker - Craftsman'', 1988) or monographs such as 's (2016) ''Cyprian Norwid. Poeta wieku dziewiętnastego'' (''Cyprian Norwid. A Poet of the Nineteenth Century''). An academic journal dedicated to the study of Norwid, ', has been published since 1983.

Works

Norwid authored numerous works, from poems, both epic and short, to plays, short stories, essays and letters. During his lifetime, according to Miłosz and Gömöri, he published only one large volume of poetry (in 1862) (although Borchardt mentions another volume from 1866). Borchardt considers his major works to be ''Vade-mecum'', ''Promethidion'' and ''Ad leones!''. Miłosz acknowledged ''Vade-mecum'' as Norwid's most influential work, but also praised the earlier '' Bema pamięci rapsod żałobny'' as one of his most famous poems.

Norwid's most extensive work,''Vade-mecum'', written between 1858 and 1865, was first published a century after his death. Some of Norwid's works have been translated into English by Walter Whipple and

Norwid authored numerous works, from poems, both epic and short, to plays, short stories, essays and letters. During his lifetime, according to Miłosz and Gömöri, he published only one large volume of poetry (in 1862) (although Borchardt mentions another volume from 1866). Borchardt considers his major works to be ''Vade-mecum'', ''Promethidion'' and ''Ad leones!''. Miłosz acknowledged ''Vade-mecum'' as Norwid's most influential work, but also praised the earlier '' Bema pamięci rapsod żałobny'' as one of his most famous poems.

Norwid's most extensive work,''Vade-mecum'', written between 1858 and 1865, was first published a century after his death. Some of Norwid's works have been translated into English by Walter Whipple and Danuta Borchardt

Danuta is a Polish feminine given name. Its diminutive is Danusia.

Notable people named Danuta include:

*Danuta Bartoszek (born 1961), long-distance runner for Canada

* Danuta Bułkowska (born 1959), former Polish champion in high jumping

* Danut ...

in the United States of America

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 contiguo ...

, and by Jerzy Pietrkiewicz and Adam Czerniawski in Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

. A number have also received translations to other languages, such as Bengali, French, German, Italian, Russian, Slovakian and Ukrainian.

From May 2024, an autograph copy of ''Vade-mecum'' is presented at a permanent exhibition in the Palace of the Commonwealth. There are also presented two albums ''Orbis I'' and ''Orbis II'', containing Norwid's original works and copies of works in various media, in addition to hand written notes, magazine cuttings and photographs.

See also

* Cyprian Norwid Theatre * List of Polish poets * Parnassism *Stanisław Wyspiański

Stanisław Mateusz Ignacy Wyspiański (; 15 January 1869 – 28 November 1907) was a Polish playwright, painter, poet, and interior and furniture designer. A patriotic writer, he created symbolic national dramas accordant with the artisti ...

, another Polish writer also called the Fourth Bard of Poland

Further reading

* Jarzębowski, Józef. ''Norwid i Zmartwychstańcy''. London: Veritas, 1960. ("Norwid and The Resurrectionists") *Kalergis, Maria. ''Listy do Adama Potockiego'' (Letters to Adam Potocki), edited by Halina Kenarowa, translated from the French by Halina Kenarowa and Róża Drojecka, Warsaw, 1986.References

Notes

Citations

External links

Speech about Norwid made by Pope John Paul II to the representatives of the Institute of Polish National Patrimony

Biography links

Profile of Cyprian Norwid

at Culture.pl

Why You Should Read Norwid, Poland's Starving Time Traveller

from Culture.pl

Collection of works

Repository of translated poems

Cyprian Kamil Norwid

collected works (Polish) * * *

' *

' *

' *

' *

' {{DEFAULTSORT:Norwid, Cyprian Kamil 1821 births 1883 deaths People from Wyszków County 19th-century Polish painters 19th-century Polish male artists 19th-century Roman Catholics Polish male sculptors Polish male dramatists and playwrights Polish Roman Catholic writers Activists of the Great Emigration 19th-century Polish sculptors 19th-century Polish poets 19th-century Polish dramatists and playwrights Polish male poets 19th-century Polish male writers 19th-century Polish philosophers Polish male painters