Cult Leader on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In modern English, ''cult'' is usually a

Sects and Cults

"

Defining Religion in American Law

(lecture). ''Conference On The Controversy Concerning Sects In French-Speaking Europe''. Sponsored by

original

on 10 November 2005.

A ''new religious movement'' (NRM) is a religious community or spiritual group of modern origins (since the mid-1800s), which has a peripheral place within its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin or part of a wider religion, in which case they are distinct from pre-existing denominations.Clarke, Peter B. 2006. ''New Religions in Global Perspective: A Study of Religious Change in the Modern World''. New York: Routledge. Siegler, Elijah. 2007. ''New Religious Movements''.

A ''new religious movement'' (NRM) is a religious community or spiritual group of modern origins (since the mid-1800s), which has a peripheral place within its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin or part of a wider religion, in which case they are distinct from pre-existing denominations.Clarke, Peter B. 2006. ''New Religions in Global Perspective: A Study of Religious Change in the Modern World''. New York: Routledge. Siegler, Elijah. 2007. ''New Religious Movements''.

Sociologist

Sociologist

Stressed to Kill: The Defense of Brainwashing; Sniper Suspect's Claim Triggers More Debate

" ''Defence Brief'' 269. Toronto: Steven Skurka & Associates. Archived from th

on 1 May 2011. has defended some so-called cults, and in 1988 argued that involvement in such movements may often have beneficial, rather than harmful effects, saying that " ere's a large research literature published in mainstream journals on the mental health effects of new religions. For the most part, the effects seem to be positive in any way that's measurable." Sipchen, Bob. 17 November 1988.

Ten Years After Jonestown, the Battle Intensifies Over the Influence of 'Alternative' Religions

" ''

''Destructive cult'' generally refers to groups whose members have, through deliberate action, physically injured or killed other members of their own group or other people. The Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance specifically limits the use of the term to religious groups that "have caused or are liable to cause loss of life among their membership or the general public."

''Destructive cult'' generally refers to groups whose members have, through deliberate action, physically injured or killed other members of their own group or other people. The Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance specifically limits the use of the term to religious groups that "have caused or are liable to cause loss of life among their membership or the general public."

A political cult is a cult with a primary interest in

A political cult is a cult with a primary interest in

The Sociology of the Ayn Rand Cult

" Retrieved 6 June 2020. Revised editions: ''

Give and Forget

/ref>

''

Sara Diamond, 1989,

''

''

pejorative

A pejorative or slur is a word or grammatical form expressing a negative or a disrespectful connotation, a low opinion, or a lack of respect toward someone or something. It is also used to express criticism, hostility, or disregard. Sometimes, a ...

term for a social group

In the social sciences, a social group can be defined as two or more people who interact with one another, share similar characteristics, and collectively have a sense of unity. Regardless, social groups come in a myriad of sizes and varieties ...

that is defined by its unusual religious

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

, spiritual, or philosophical

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Som ...

beliefs and rituals

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized, b ...

, or its common interest in a particular personality

Personality is the characteristic sets of behaviors, cognitions, and emotional patterns that are formed from biological and environmental factors, and which change over time. While there is no generally agreed-upon definition of personality, mos ...

, object, or goal

A goal is an idea of the future or desired result that a person or a group of people envision, plan and commit to achieve. People endeavour to reach goals within a finite time by setting deadlines.

A goal is roughly similar to a purpose or ...

. This sense of the term is controversial and weakly defined—having divergent definitions both in popular culture

Popular culture (also called mass culture or pop culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as, popular art or mass art) and objects that are dominant or prevalent in ...

and academia—and has also been an ongoing source of contention among scholars across several fields of study. Richardson, James T. 1993. "Definitions of Cult: From Sociological-Technical to Popular-Negative." '' Review of Religious Research'' 34(4):348–56. . .

An older sense of the word involves a set of religious devotional practices that are conventional within their culture, related to a particular figure, and often associated with a particular place. References to the "cult" of a particular Catholic saint, or the imperial cult of ancient Rome, for example, use this sense of the word.

While the literal and original sense of the word remains in use, a derived sense of "excessive devotion" arose in the 19th century.Compare the ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

'' note for usage in 1875: "cult:…b. A relatively small group of people having (esp. religious) beliefs or practices regarded by others as strange or sinister, or as exercising excessive control over members.… 1875 ''Brit. Mail 30'' Jan. 13/1 Buffaloism is, it would seem, a cult, a creed, a secret community, the members of which are bound together by strange and weird vows, and listen in hidden conclave to mysterious lore."

Then, beginning in the 1930s, cults became an object of sociological study within the context of the study of religious behavior. Since the 1940s, the Christian countercult movement has opposed some sect

A sect is a subgroup of a religious, political, or philosophical belief system, usually an offshoot of a larger group. Although the term was originally a classification for religious separated groups, it can now refer to any organization that b ...

s and new religious movement

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as alternative spirituality or a new religion, is a religious or spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin or th ...

s, labeling them "cults" because of their unorthodox beliefs. Since the 1970s, the secular anti-cult movement

The anti-cult movement (abbreviated ACM, and also known as the countercult movement) consists of various governmental and non-governmental organizations and individuals that seek to raise awareness of cults, uncover coercive practices used to a ...

has opposed certain groups and, as a reaction to acts of violence, frequently charged those cults with practicing mind control

Brainwashing (also known as mind control, menticide, coercive persuasion, thought control, thought reform, and forced re-education) is the concept that the human mind can be altered or controlled by certain psychological techniques. Brainwashi ...

. Scholars and the media have disputed some of the claims and actions of anti-cult movements, leading to further public controversy.

Sociological classifications of religious movements

Various sociological classifications of religious movements have been proposed by scholars. In the sociology of religion, the most widely used classification is the church-sect typology. The typology is differently construed by different sociolog ...

may identify a cult as a social group with socially deviant or novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

beliefs and practices, although this is often unclear.Shaw, Chuck. 2005.Sects and Cults

"

Greenville Technical College

Greenville Technical College is a Public college, public community college in Greenville, South Carolina. Founded in 1960, it began operation in September 1962.

Campuses

Greenville Tech currently has six locations in Greenville County:

*Barton C ...

. Retrieved 21 March 2013. Other researchers present a less-organized picture of cults, saying that they arise spontaneously around novel beliefs and practices. Groups labelled as "cults" range in size from local groups with a few followers to international organizations with millions of adherents.

Definition

In the English-speaking world, the term ''cult'' often carriesderogatory

A pejorative or slur is a word or grammatical form expressing a negative or a disrespectful connotation, a low opinion, or a lack of respect toward someone or something. It is also used to express criticism, hostility, or disregard. Sometimes, a ...

connotations. In this sense, it has been considered a subjective

Subjective may refer to:

* Subjectivity, a subject's personal perspective, feelings, beliefs, desires or discovery, as opposed to those made from an independent, objective, point of view

** Subjective experience, the subjective quality of conscio ...

term, used as an ''ad hominem

''Ad hominem'' (), short for ''argumentum ad hominem'' (), refers to several types of arguments, most of which are fallacious.

Typically, this term refers to a rhetorical strategy where the speaker attacks the character, motive, or some othe ...

'' attack against groups with differing doctrines or practices. As such, religion scholar Megan Goodwin has defined the term ''cult'', when it is used by the layperson, as often being shorthand for a "religion I don't like".

In the 1970s, with the rise of secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

anti-cult movement

The anti-cult movement (abbreviated ACM, and also known as the countercult movement) consists of various governmental and non-governmental organizations and individuals that seek to raise awareness of cults, uncover coercive practices used to a ...

s, scholars (though not the general public) began to abandon the use of the term ''cult''. According to ''The Oxford Handbook of Religious Movements'', "by the end of the decade, the term 'new religions' would virtually replace the term 'cult' to describe all of those leftover groups that did not fit easily under the label of church or sect

A sect is a subgroup of a religious, political, or philosophical belief system, usually an offshoot of a larger group. Although the term was originally a classification for religious separated groups, it can now refer to any organization that b ...

."

Sociologist Amy Ryan (2000) has argued for the need to differentiate those groups that may be dangerous from groups that are more benign. Ryan notes the sharp differences between definitions offered by cult opponents, who tend to focus on negative characteristics, and those offered by sociologists, who aim to create definitions that are value-free. The movements themselves may have different definitions of religion as well. George Chryssides also cites a need to develop better definitions to allow for common ground in the debate. Casino (1999) presents the issue as crucial to international human rights laws. Limiting the definition of religion may interfere with freedom of religion, while too broad a definition may give some dangerous or abusive groups "a limitless excuse for avoiding all unwanted legal obligations."Casino. Bruce J. 15 March 1999.Defining Religion in American Law

(lecture). ''Conference On The Controversy Concerning Sects In French-Speaking Europe''. Sponsored by

CESNUR

CESNUR (Centro Studi sulle Nuove Religioni, "Center for Studies on New Religions"), is a non-profit organization based in Turin, Italy that studies new religious movements and opposes the anti-cult movement. It was established in 1988 by Massim ...

and CLIMS. Archived from thoriginal

on 10 November 2005.

New religious movements

Prentice Hall

Prentice Hall was an American major educational publisher owned by Savvas Learning Company. Prentice Hall publishes print and digital content for the 6–12 and higher-education market, and distributes its technical titles through the Safari B ...

. . In 1999, Eileen Barker estimated that NRMs, of which some but not all have been labelled as cults, number in the tens of thousands worldwide, most of which originated in Asia or Africa; and that the great majority of which have only a few members, some have thousands and only very few have more than a million. Barker, Eileen. 1999. "New Religious Movements: their incidence and significance." ''New Religious Movements: Challenge and Response'', edited by B. Wilson and J. Cresswell. Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law, ...

. . In 2007, religious scholar Elijah Siegler commented that, although no NRM had become the dominant faith in any country, many of the concepts which they had first introduced (often referred to as "New Age

New Age is a range of spiritual or religious practices and beliefs which rapidly grew in Western society during the early 1970s. Its highly eclectic and unsystematic structure makes a precise definition difficult. Although many scholars consi ...

" ideas) have become part of worldwide mainstream culture.

Scholarly studies

Sociologist

Sociologist Max Weber

Maximilian Karl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German Sociology, sociologist, historian, jurist and political economy, political economist, who is regarded as among the most important theorists of the development of Modernity, ...

(1864–1920) found that cults based on charisma

Charisma () is a personal quality of presence or charm that compels its subjects.

Scholars in sociology, political science, psychology, and management reserve the term for a type of leadership seen as extraordinary; in these fields, the term "ch ...

tic leadership often follow the routinization of charisma

Charismatic authority is a concept of leadership developed by the German sociologist Max Weber. It involves a type of organization or a type of leadership in which authority derives from the charisma of the leader. This stands in contrast to two o ...

.

The concept of a ''cult'' as a sociological classification, however, was introduced in 1932 by American sociologist Howard P. Becker as an expansion of German theologian Ernst Troeltsch

Ernst Peter Wilhelm Troeltsch (; ; 17 February 1865 – 1 February 1923) was a German liberal Protestant theologian, a writer on the philosophy of religion and the philosophy of history, and a classical liberal politician. He was a member of ...

's '' church–sect typology''. Troeltsch's aim was to distinguish between three main types of religious behaviour: churchly, sectarian

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

, and mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

.

Becker further bisected Troeltsch's first two categories: ''church'' was split into ''ecclesia'' and ''denomination''; and ''sect'' into ''sect

A sect is a subgroup of a religious, political, or philosophical belief system, usually an offshoot of a larger group. Although the term was originally a classification for religious separated groups, it can now refer to any organization that b ...

'' and ''cult''. Like Troeltsch's "mystical religion", Becker's ''cult'' refers to small religious groups that lack in organization and emphasize the private nature of personal beliefs. Later sociological formulations built on such characteristics, placing an additional emphasis on cults as deviant religious groups, "deriving their inspiration from outside of the predominant religious culture." This is often thought to lead to a high degree of tension between the group and the more mainstream culture surrounding it, a characteristic shared with religious sects. According to this sociological terminology, ''sects'' are products of religious schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

and therefore maintain a continuity with traditional beliefs and practices, whereas ''cults'' arise spontaneously around novel beliefs and practices.

In the early 1960s, sociologist John Lofland, living with South Korean missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

Young Oon Kim and some of the first American Unification Church

The Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, widely known as the Unification Church, is a new religious movement, whose members are called Unificationists, or "Moonie (nickname), Moonies". It was officially founded on 1 May 1954 unde ...

members in California, studied their activities in trying to promote their beliefs and win new members. Lofland noted that most of their efforts were ineffective and that most of the people who joined did so because of personal relationships with other members, often family relationships. Lofland published his findings in 1964 as a doctoral thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144 ...

entitled "The World Savers: A Field Study of Cult Processes", and in 1966 in book form by Prentice-Hall

Prentice Hall was an American major educational publisher owned by Savvas Learning Company. Prentice Hall publishes print and digital content for the 6–12 and higher-education market, and distributes its technical titles through the Safari B ...

as '' Doomsday Cult: A Study of Conversion, Proselytization and Maintenance of Faith''. It is considered to be one of the most important and widely cited studies of the process of religious conversion.

Sociologist Roy Wallis (1945–1990) argued that a cult is characterized by "epistemological

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-relia ...

," meaning that "the cult has no clear locus of final authority beyond the individual member." Cults, according to Wallis, are generally described as "oriented towards the problems of individuals, loosely structured, tolerant ndnon-exclusive," making "few demands on members," without possessing a "clear distinction between members and non-members," having "a rapid turnover of membership" and as being transient collectives with vague boundaries and fluctuating belief systems. Wallis asserts that cults emerge from the "cultic milieu

The social environment, social context, sociocultural context or milieu refers to the immediate physical and social setting in which people live or in which something happens or develops. It includes the culture that the individual was educate ...

".

J. Gordon Melton stated that, in 1970, "one could count the number of active researchers on new religions on one's hands." However, James R. Lewis writes that the "meteoric growth" in this field of study can be attributed to the cult controversy of the early 1970s. Because of "a wave of nontraditional religiosity" in the late 1960s and early 1970s, academics perceived new religious movements as different phenomena from previous religious innovations.

In 1978, Bruce Campbell noted that cults are associated with beliefs in a divine

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.divine< ...

element in the individual; it is either ''soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '':wikt:soul, soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The ea ...

'', ''self

The self is an individual as the object of that individual’s own reflective consciousness. Since the ''self'' is a reference by a subject to the same subject, this reference is necessarily subjective. The sense of having a self—or ''selfhood ...

'', or ''true self''. Cults are inherently ephemeral

Ephemerality (from the Greek word , meaning 'lasting only one day') is the concept of things being transitory, existing only briefly. Academically, the term ephemeral constitutionally describes a diverse assortment of things and experiences, fr ...

and loosely organized. There is a major theme in many of the recent works that show the relationship between cults and mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

. Campbell, describing ''cults'' as non-traditional religious groups based on belief in a divine element in the individual, brings two major types of such to attention—mystical and instrumental—dividing cults into either occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism ...

or metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of consci ...

assembly. There is also a third type, the service-oriented, as Campbell states that "the kinds of stable forms which evolve in the development of religious organization will bear a significant relationship to the content of the religious experience of the founder or founders."Campbell, Bruce. 1978. "A Typology of Cults." ''Sociology Analysis''. Santa Barbara.

Dick Anthony

Dick Anthony is a forensic psychologist noted for his writings on the validity of brainwashing as a determiner of behavior, a prolific researcher of the social and psychological aspects of involvement in new religious movements.

Academic career ...

, a forensic psychologist

Forensic psychology is the development and application of scientific knowledge and methods to help answer legal questions arising in criminal, civil, contractual, or other judicial proceedings. Forensic psychology includes both research on various ...

known for his criticism of brainwashing

Brainwashing (also known as mind control, menticide, coercive persuasion, thought control, thought reform, and forced re-education) is the concept that the human mind can be altered or controlled by certain psychological techniques. Brainwashi ...

theory of conversion,Oldenburg, Don. 0032003.Stressed to Kill: The Defense of Brainwashing; Sniper Suspect's Claim Triggers More Debate

" ''Defence Brief'' 269. Toronto: Steven Skurka & Associates. Archived from th

on 1 May 2011. has defended some so-called cults, and in 1988 argued that involvement in such movements may often have beneficial, rather than harmful effects, saying that " ere's a large research literature published in mainstream journals on the mental health effects of new religions. For the most part, the effects seem to be positive in any way that's measurable." Sipchen, Bob. 17 November 1988.

Ten Years After Jonestown, the Battle Intensifies Over the Influence of 'Alternative' Religions

" ''

Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

.''

In their 1996 book ''Theory of Religion'', American sociologists Rodney Stark and William Sims Bainbridge propose that the formation of cults can be explained through the rational choice theory

Rational choice theory refers to a set of guidelines that help understand economic and social behaviour. The theory originated in the eighteenth century and can be traced back to political economist and philosopher, Adam Smith. The theory postul ...

. In ''The Future of Religion'' they comment that, "in the beginning, all religions are obscure, tiny, deviant cult movements." According to Marc Galanter, Professor of Psychiatry at NYU, typical reasons why people join cults include a search for community and a spiritual quest. Stark and Bainbridge, in discussing the process by which individuals join new religious groups, have even questioned the utility of the concept of '' conversion'', suggesting that '' affiliation'' is a more useful concept.

Subcategories

Destructive cults

''Destructive cult'' generally refers to groups whose members have, through deliberate action, physically injured or killed other members of their own group or other people. The Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance specifically limits the use of the term to religious groups that "have caused or are liable to cause loss of life among their membership or the general public."

''Destructive cult'' generally refers to groups whose members have, through deliberate action, physically injured or killed other members of their own group or other people. The Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance specifically limits the use of the term to religious groups that "have caused or are liable to cause loss of life among their membership or the general public." Psychologist

A psychologist is a professional who practices psychology and studies mental states, perceptual, cognitive, emotional, and social processes and behavior. Their work often involves the experimentation, observation, and interpretation of how ...

Michael Langone, executive director of the anti-cult group International Cultic Studies Association

The International Cultic Studies Association (ICSA) is a non-profit anti-cult organization focusing on groups it defines as "cultic" and their processes. It publishes the ''International Journal of Cultic Studies'' and other materials.

History ...

, defines a destructive cult as "a highly manipulative group which exploits and sometimes physically and/or psychologically damages members and recruits."

John Gordon Clark

John 'Jack' Gordon Clark (1926–1999) was a Harvard psychiatrist known for his research on the alleged damaging effects of cults.

He was the target of harassment from the Church of Scientology after he testified against it to the Vermont legi ...

argued that totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and regul ...

systems of governance and an emphasis on money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money ar ...

making are characteristics of a destructive cult. In ''Cults and the Family'', the authors cite Shapiro, who defines a ''destructive cultism'' as a sociopathic

Psychopathy, sometimes considered synonymous with sociopathy, is characterized by persistent antisocial behavior, impaired empathy and remorse, and bold, disinhibited, and egotistical traits. Different conceptions of psychopathy have been u ...

syndrome

A syndrome is a set of medical signs and symptoms which are correlated with each other and often associated with a particular disease or disorder. The word derives from the Greek σύνδρομον, meaning "concurrence". When a syndrome is paired ...

, whose distinctive qualities include: "behavioral and personality changes, loss of personal identity

Personal identity is the unique numerical identity of a person over time. Discussions regarding personal identity typically aim to determine the necessary and sufficient conditions under which a person at one time and a person at another time ca ...

, cessation of scholastic activities, estrangement from family, disinterest in society and pronounced mental control and enslavement by cult leaders."

In the opinion of Sociology Professor Benjamin Zablocki of Rutgers University

Rutgers University (; RU), officially Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, is a public land-grant research university consisting of four campuses in New Jersey. Chartered in 1766, Rutgers was originally called Queen's College, and wa ...

, ''destructive cults'' are at high risk of becoming abusive to members, stating that such is in part due to members' adulation

Flattery (also called adulation or blandishment) is the act of giving excessive compliments, generally for the purpose of ingratiating oneself with the subject. It is also used in pick-up lines when attempting to initiate sexual or romantic cou ...

of charismatic leaders contributing to the leaders becoming corrupted by power. According to Barrett, the most common accusation made against destructive cults is sexual abuse

Sexual abuse or sex abuse, also referred to as molestation, is abusive sexual behavior by one person upon another. It is often perpetrated using force or by taking advantage of another. Molestation often refers to an instance of sexual assa ...

. According to Kranenborg, some groups are risky when they advise their members not to use regular medical care. Kranenborg, Reender. 1996. "Sekten... gevaarlijk of niet? ults... dangerous or not? (in Dutch). ''Religieuze bewegingen in Nederland'' 31. Free University Amsterdam

The Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (abbreviated as ''VU Amsterdam'' or simply ''VU'' when in context) is a public research university in Amsterdam, Netherlands, being founded in 1880. The VU Amsterdam is one of two large, publicly funded research ...

. . . This may extend to physical and psychological harm.

Writing about Bruderhof communities

The (; 'place of brothers') is an Anabaptist Christian movement that was founded in Germany in 1920 by Eberhard Arnold. The movement has communities in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Austria, Paraguay, and Australia.

The Bru ...

in the book '' Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field'', Julius H. Rubin said that American religious innovation created an unending diversity of sects. These "new religious movements…gathered new converts and issued challenges to the wider society. Not infrequently, public controversy, contested narratives and litigation result." In his work ''Cults in Context'' author Lorne L. Dawson writes that although the Unification Church

The Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, widely known as the Unification Church, is a new religious movement, whose members are called Unificationists, or "Moonie (nickname), Moonies". It was officially founded on 1 May 1954 unde ...

"has not been shown to be violent or volatile," it has been described as a destructive cult by "anticult crusaders." In 2002, the German government was held by the Federal Constitutional Court

The Federal Constitutional Court (german: link=no, Bundesverfassungsgericht ; abbreviated: ) is the supreme constitutional court for the Federal Republic of Germany, established by the constitution or Basic Law () of Germany. Since its in ...

to have defamed the Osho movement

The Rajneesh movement are people inspired by the Indian mystic Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (1931–1990), also known as Osho, particularly initiated disciples who are referred to as "neo-sannyasins". They used to be known as ''Rajneeshees'' or "Orang ...

by referring to it, among other things, as a "destructive cult" with no factual basis.

Some researchers have criticized the usage of the term ''destructive cult'', writing that it is used to describe groups which are not necessarily harmful in nature to themselves or others. In his book ''Understanding New Religious Movements'', John A. Saliba John A. Saliba is a Maltese-born Jesuit priest, a professor of religious studies at the University of Detroit Mercy and a noted writer and researcher in the field of new religious movements.

Saliba has advocated a conciliatory approach towards n ...

writes that the term is overgeneralized. Saliba sees the Peoples Temple as the "paradigm of a destructive cult", where those that use the term are implying that other groups will also commit mass suicide

Mass suicide is a form of suicide, occurring when a group of people simultaneously kill themselves.

Overview

Mass suicide sometimes occurs in religious settings. In war, defeated groups may resort to mass suicide rather than being captured. Su ...

.

Doomsday cults

''Doomsday cult'' is an expression which is used to describe groups that believe inApocalypticism

Apocalypticism is the religious belief that the end of the world is imminent, even within one's own lifetime. This belief is usually accompanied by the idea that civilization will soon come to a tumultuous end due to some sort of catastrophic ...

and Millenarianism

Millenarianism or millenarism (from Latin , "containing a thousand") is the belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a coming fundamental transformation of society, after which "all things will be changed". Millenaria ...

, and it can also be used to refer both to groups that predict disaster

A disaster is a serious problem occurring over a short or long period of time that causes widespread human, material, economic or environmental loss which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources ...

, and groups that attempt to bring it about. In the 1950s, American social psychologist

Social psychology is the scientific study of how thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by the real or imagined presence of other people or by social norms. Social psychologists typically explain human behavior as a result of the rela ...

Leon Festinger

Leon Festinger (8 May 1919 – 11 February 1989) was an American social psychologist who originated the theory of cognitive dissonance and social comparison theory. The rejection of the previously dominant behaviorist view of social psychol ...

and his colleagues observed members of a small UFO religion

A UFO religion is any religion in which the existence of extraterrestrial (ET) entities operating unidentified flying objects (UFOs) is an element of belief. Typically, adherents of such religions believe the ETs to be interested in the welfar ...

called the Seekers for several months, and recorded their conversations both prior to and after a failed prophecy from their charismatic leader. Their work was later published in the book '' When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World''. In the late 1980s, doomsday cults were a major topic of news reports, with some reporters and commentators considering them a serious threat to society. A 1997 psychological study by Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter found that people turned to a cataclysmic world view

A worldview or world-view or ''Weltanschauung'' is the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual's or society's knowledge, culture, and point of view. A worldview can include natural ...

after they had repeatedly failed to find meaning in mainstream movements. People also strive to find meaning in global events such as the turn of the millennium when many predicted it prophetically marked the end of an age and thus the end of the world. An ancient Mayan calendar ended at the year 2012 and many anticipated catastrophic disasters would rock the Earth.

Political cults

A political cult is a cult with a primary interest in

A political cult is a cult with a primary interest in political action

In sociology, social action, also known as Weberian social action, is an act which takes into account the actions and reactions of individuals (or ' agents'). According to Max Weber, "Action is 'social' insofar as its subjective meaning takes a ...

and ideology.Tourish, Dennis, and Tim Wohlforth

Timothy Andrew Wohlforth (May 15, 1933 – August 23, 2019), was a United States Trotskyist leader. On leaving the Trotskyist movement he became a writer of crime fiction and of politically oriented non-fiction.

As a student, Wohlforth joined ...

. 2000. '' On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left''. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe

M. E. Sharpe, Inc., an academic publisher, was founded by Myron Sharpe in 1958 with the original purpose of publishing translations from Russian in the social sciences and humanities. These translations were published in a series of journals, the ...

. Groups that some have described as "political cults", mostly advocating far-left

Far-left politics, also known as the radical left or the extreme left, are politics further to the left on the left–right political spectrum than the standard political left. The term does not have a single definition. Some scholars consider ...

or far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of bein ...

agendas, have received some attention from journalists and scholars. In their 2000 book '' On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left'', Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth

Timothy Andrew Wohlforth (May 15, 1933 – August 23, 2019), was a United States Trotskyist leader. On leaving the Trotskyist movement he became a writer of crime fiction and of politically oriented non-fiction.

As a student, Wohlforth joined ...

discuss about a dozen organizations in the United States and Great Britain that they characterize as cults. In a separate article, Tourish says that in his usage: The word cult is not a term of abuse, as this paper tries to explain. It is nothing more than a shorthand expression for a particular set of practices that have been observed in a variety of dysfunctional organisations.In 1990, Lucy Patrick commented:

Although we live in a democracy, cult behavior manifests itself in our unwillingness to question the judgment of our leaders, our tendency to devalue outsiders and to avoid dissent. We can overcome cult behavior, he says, by recognizing that we have dependency needs that are inappropriate for mature people, by increasing anti-authoritarian education, and by encouraging personal autonomy and the free exchange of ideas.In Iran, a "cult of

Khomeini

Ruhollah Khomeini, Ayatollah Khomeini, Imam Khomeini ( , ; ; 17 May 1900 – 3 June 1989) was an Iranian political and religious leader who served as the first supreme leader of Iran from 1979 until his death in 1989. He was the founder of ...

" developed into a "secular religion". According to Iranian author Amir Taheri

Amir Taheri ( fa, امیر طاهری; born 9 June 1942) is an Iranian-born columnist and activist author based in Europe. His writings focus on the Middle East affairs and topics related to Islamic terrorism. He has been the subject of many c ...

, Khomeini is called imam, making a "Twelver Shiism into a cult of Thirteen." Khomeini’s image is engraved in giant rocks and mountain slopes, prayers begin and end with his name, and his fatwas remain valid beyond his death (something that goes against Shiite principles). Also slogans such as "God, Koran, Khomeini" or "God is One, Khomeini is the Leader" are used as war cries of the Hezballah in Iran. Even though Khomeini’s photographs still hang in many government offices, it is said that by the late 1990s “Khomeini’s cult had faded”.

Ayn Rand Institute

Followers ofAyn Rand

Alice O'Connor (born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum;, . Most sources transliterate her given name as either ''Alisa'' or ''Alissa''. , 1905 – March 6, 1982), better known by her pen name Ayn Rand (), was a Russian-born American writer and p ...

have been characterized as a cult by economist Murray N. Rothbard

Murray Newton Rothbard (; March 2, 1926 – January 7, 1995) was an American economist of the Austrian School, economic historian, political theorist, and activist. Rothbard was a central figure in the 20th-century American libertarian m ...

during her lifetime, and later by Michael Shermer

Michael Brant Shermer (born September 8, 1954) is an American science writer, historian of science, executive director of The Skeptics Society, and founding publisher of '' Skeptic'' magazine, a publication focused on investigating pseudoscientif ...

.Rothbard, Murray

Murray Newton Rothbard (; March 2, 1926 – January 7, 1995) was an American economist of the Austrian School, economic historian, political theorist, and activist. Rothbard was a central figure in the 20th-century American libertarian ...

. 1972.The Sociology of the Ayn Rand Cult

" Retrieved 6 June 2020. Revised editions: ''

Liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

'' magazine (1987), and Center for Libertarian Studies

The Center for Libertarian Studies (CLS) was a libertarian and anarcho-capitalist oriented educational organization founded in 1976 by Murray Rothbard and Burton Blumert, which grew out of the Libertarian Scholars Conferences. That year, the conf ...

(1990). The core group around Rand was called the "Collective", which are now defunct; the chief group which is disseminating Rand's ideas today is the Ayn Rand Institute. Although the Collective advocated an individualist philosophy, Rothbard claimed that it was organized in the manner of a "Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establish ...

" organization.

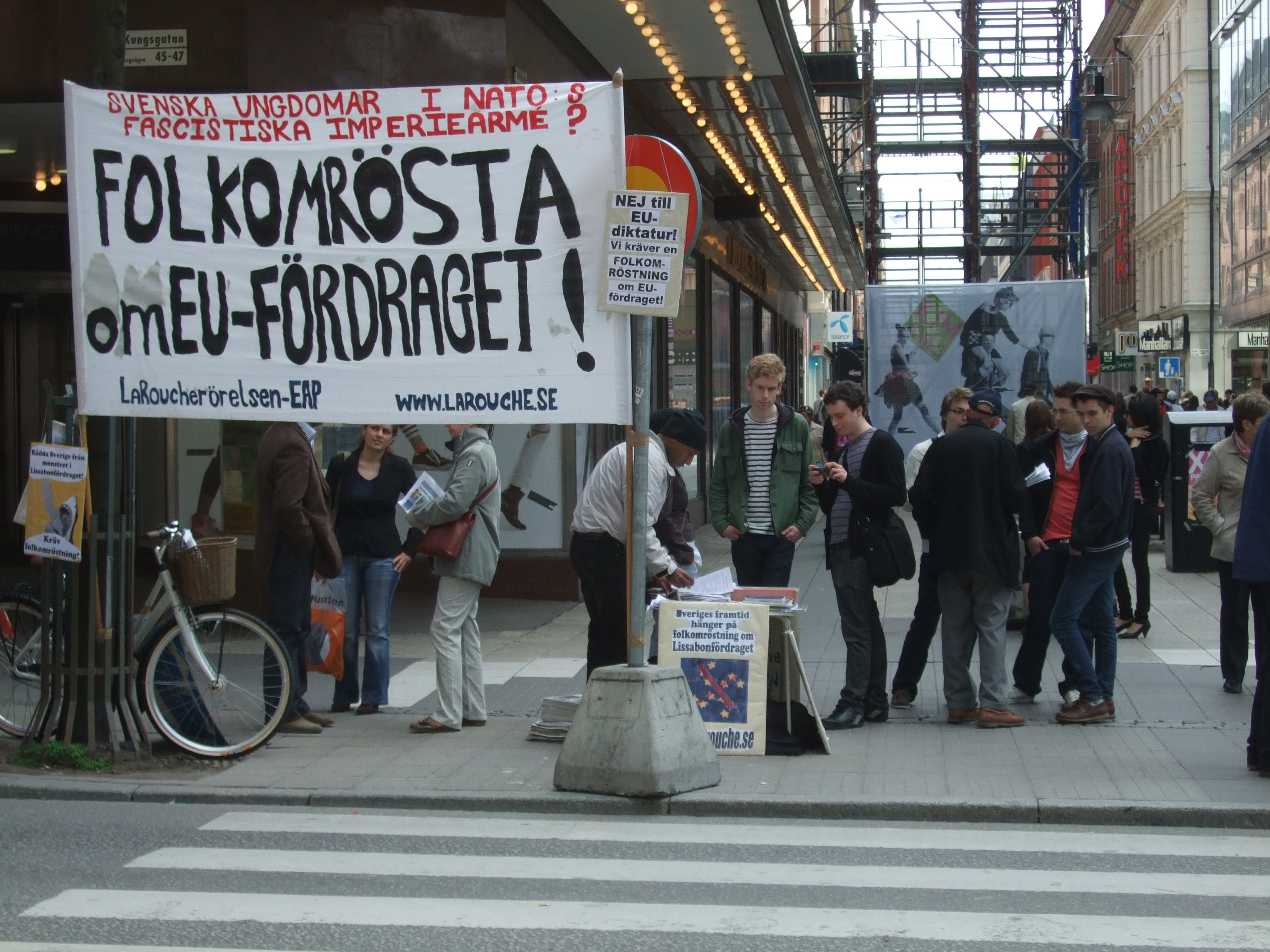

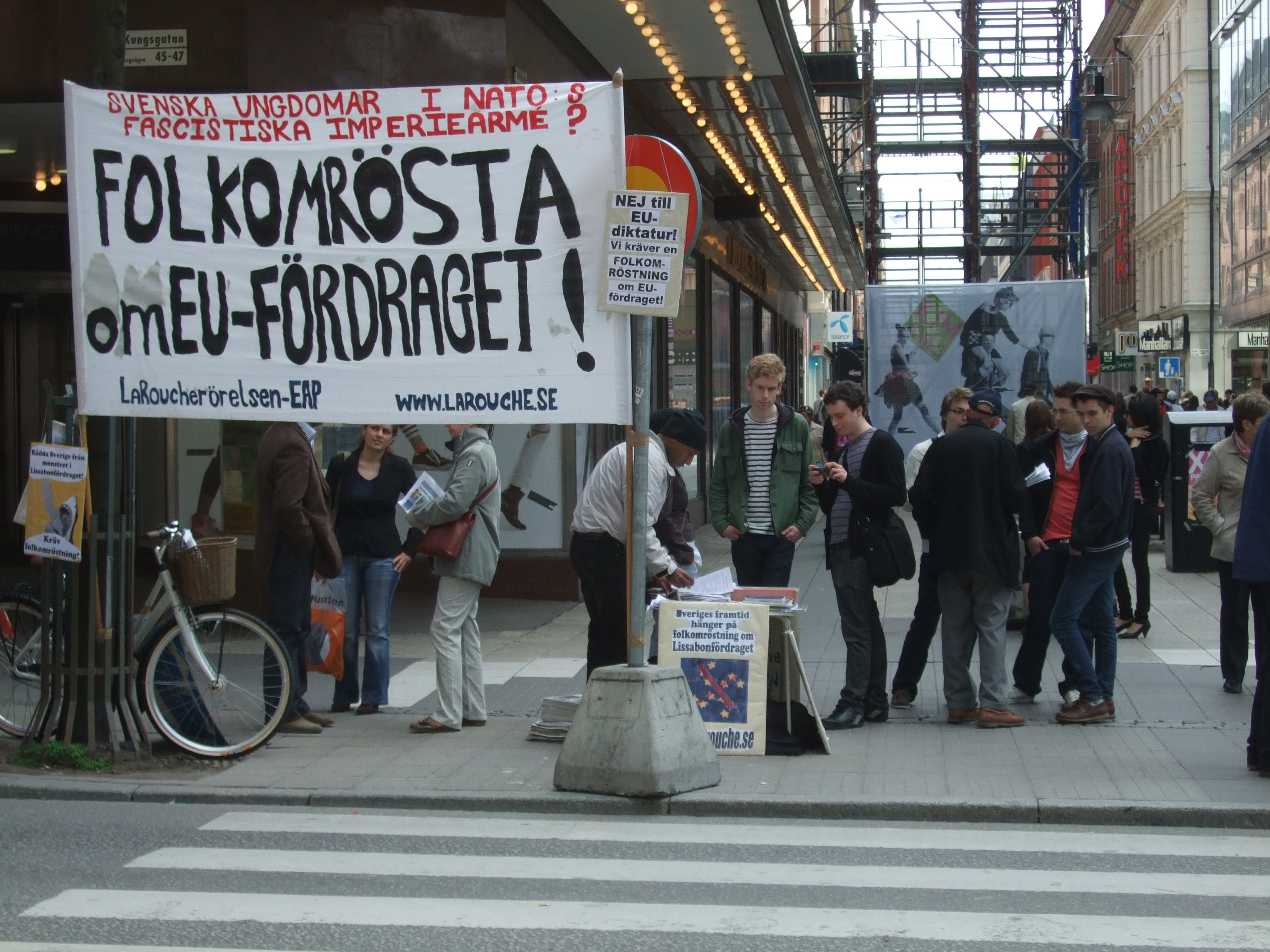

LaRouche movement

TheLaRouche movement

The LaRouche movement is a political and cultural network promoting the late Lyndon LaRouche and his ideas. It has included many organizations and companies around the world, which campaign, gather information and publish books and periodicals. ...

is a political and cultural network promoting the late Lyndon LaRouche

Lyndon Hermyle LaRouche Jr. (September 8, 1922 – February 12, 2019) was an American political activist who founded the LaRouche movement and its main organization the National Caucus of Labor Committees (NCLC). He was a prominent conspira ...

and his ideas. It has included many organizations and companies around the world, which campaign, gather information and publish books and periodicals. It has been called "cult-like" by ''The New York Times''.

The movement originated within the radical leftist student politics of the 1960s. In the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of candidates ran in state Democratic

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

primaries in the United States on the 'LaRouche platform', while Lyndon LaRouche repeatedly campaigned for presidential nomination. However, the LaRouche movement is often considered far-right.King 1989, pp. 132–133. During its peak in the 1970s and 1980s, the LaRouche movement developed a private intelligence agency and contacts with foreign governments.

New Acropolis

An Argentinianesoteric

Western esotericism, also known as esotericism, esoterism, and sometimes the Western mystery tradition, is a term scholars use to categorise a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas a ...

group founded in 1957 by former theosophist

Theosophy is a religion established in the United States during the late 19th century. It was founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and draws its teachings predominantly from Blavatsky's writings. Categorized by scholars of religion a ...

Jorge Angel Livraga

Jorge is a Spanish and Portuguese given name. It is derived from the Greek name Γεώργιος (''Georgios'') via Latin ''Georgius''; the former is derived from (''georgos''), meaning "farmer" or "earth-worker".

The Latin form ''Georgius' ...

, the New Acropolis Cultural Association has been described by scholars as an ultra-conservative, neo-fascist and white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

paramilitary group

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

. The group itself denies such descriptions.

Unification Church

Founded by North Korea-bornSun Myung Moon

Sun Myung Moon (; born Yong Myung Moon; 6 January 1920 – 3 September 2012) was a Korean religious leader, also known for his business ventures and support for conservative political causes. A messiah claimant, he was the founder of the Unif ...

, the Unification Church

The Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, widely known as the Unification Church, is a new religious movement, whose members are called Unificationists, or "Moonie (nickname), Moonies". It was officially founded on 1 May 1954 unde ...

(also known as the Unification movement) holds a strong anti-Communist position. In the 1940s, Moon cooperated with members of the Communist Party of Korea

The Communist Party of Korea () was a communist party in Korea. It was founded during a secret meeting in Seoul in 1925. The Governor-General of Korea had banned communist and socialist parties under the Peace Preservation Law (see History of Kor ...

in the Korean independence movement

The Korean independence movement was a military and diplomatic campaign to achieve the independence of Korea from Japan. After the Japanese annexation of Korea in 1910, Korea's domestic resistance peaked in the March 1st Movement of 1919, whic ...

against Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent for ...

. However, after the Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top: ...

(1950–1953), he became an outspoken anti-communist. Moon viewed the Cold War between democracy and communism as the final conflict between God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

and Satan

Satan,, ; grc, ὁ σατανᾶς or , ; ar, شيطانالخَنَّاس , also known as the Devil, and sometimes also called Lucifer in Christianity, is an entity in the Abrahamic religions that seduces humans into sin or falsehoo ...

, with divided Korea as its primary front line

A front line (alternatively front-line or frontline) in military terminology is the position(s) closest to the area of conflict of an armed force's personnel and equipment, usually referring to land forces. When a front (an intentional or unint ...

. Soon after its founding the Unification movement began supporting anti-communist organizations, including the World League for Freedom and Democracy

The World League for Freedom and Democracy (WLFD) is an international non-governmental organization of anti-communist politicians and groups. It was founded in 1952 as the World Anti-Communist League (WACL) under the initiative of Chiang Kai-shek ...

founded in 1966 in Taipei

Taipei (), officially Taipei City, is the capital and a special municipality of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Located in Northern Taiwan, Taipei City is an enclave of the municipality of New Taipei City that sits about southwest of the ...

, Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northea ...

(Taiwan), by Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

, and the Korean Culture and Freedom Foundation

The Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, widely known as the Unification Church, is a new religious movement, whose members are called Unificationists, or "Moonies". It was officially founded on 1 May 1954 under the name Holy Spi ...

, an international public diplomacy

In international relations, public diplomacy or people's diplomacy, broadly speaking, is any of the various government-sponsored efforts aimed at communicating directly with foreign publics to establish a dialogue designed to inform and influen ...

organization which also sponsored Radio Free Asia.

In 1974 the Unification Church supported Republican President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was t ...

and rallied in his favor after the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's continual ...

, with Nixon thanking personally for it. In 1975 Moon spoke at a government sponsored rally against potential North Korean military aggression on Yeouido Island

Yeouido (Hangul: 여의도, en, Yoi Island or Yeoui Island) is a large island (or eyot) on the Han River in Seoul, South Korea. It is Seoul's main finance and investment banking district. Its 8.4 square kilometers are home to some 30,988 people ...

in Seoul to an audience of around 1 million. The Unification movement was criticized by both the mainstream media

In journalism, mainstream media (MSM) is a term and abbreviation used to refer collectively to the various large mass news media that influence many people and both reflect and shape prevailing currents of thought. Chomsky, Noam, ''"What makes ma ...

and the alternative press for its anti-communist activism, which many said could lead to World War Three and a nuclear holocaust

A nuclear holocaust, also known as a nuclear apocalypse, nuclear Armageddon, or atomic holocaust, is a theoretical scenario where the mass detonation of nuclear weapons causes globally widespread destruction and radioactive fallout. Such a scen ...

.Thomas Ward, 2006Give and Forget

/ref>

''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', 21 January 1992

In 1977, the Subcommittee on International Organizations of the Committee on International Relations The Subcommittee on International Organizations of the Committee on International Relations (also known as the Fraser Committee) was a committee of the U.S. House of Representatives which met in 1976 and 1977 and conducted an investigation into the ...

, of the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together the ...

, found that the South Korean intelligence agency, the KCIA, had used the movement to gain political influence with the United States and that some members had worked as volunteers in Congressional offices. Together they founded the Korean Cultural Freedom Foundation, a nonprofit organization which acted as a public diplomacy

In international relations, public diplomacy or people's diplomacy, broadly speaking, is any of the various government-sponsored efforts aimed at communicating directly with foreign publics to establish a dialogue designed to inform and influen ...

campaign for the Republic of Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its ea ...

.Spiritual warfare: the politics of the Christian rightSara Diamond, 1989,

Pluto Press

Pluto Press is a British independent book publisher based in London, founded in 1969. Originally, it was the publishing arm of the International Socialists (today known as the Socialist Workers Party), until it changed hands and was replaced ...

, Page 58 The committee also investigated possible KCIA influence on the Unification Church's campaign in support of Nixon.

In 1980, members founded CAUSA International, an anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and th ...

educational organization based in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

."Moon's 'Cause' Takes Aim At Communism in Americas." ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

''. August 28, 1983 In the 1980s, it was active in 21 countries. In the United States, it sponsored educational conferences for evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual exp ...

and fundamentalist

Fundamentalism is a tendency among certain groups and individuals that is characterized by the application of a strict literal interpretation to scriptures, dogmas, or ideologies, along with a strong belief in the importance of distinguishin ...

Christian leadersSun Myung Moon's Followers Recruit Christians to Assist in Battle Against Communism''

Christianity Today

''Christianity Today'' is an evangelical Christian media magazine founded in 1956 by Billy Graham. It is published by Christianity Today International based in Carol Stream, Illinois. ''The Washington Post'' calls ''Christianity Today'' "evan ...

'', June 15, 1985 as well as seminars and conferences for Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

staffers, Hispanic Americans

Hispanic and Latino Americans ( es, Estadounidenses hispanos y latinos; pt, Estadunidenses hispânicos e latinos) are Americans of Spanish and/or Latin American ancestry. More broadly, these demographics include all Americans who identify as ...

and conservative activists.Church Spends Millions On Its Image''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'', 1984-09-17. "Another church political arm, Causa International, which preaches a philosophy it calls "God-ism," has been spending millions of dollars on expense-paid seminars and conferences for Senate staffers, Hispanic Americans and conservative activists. It also has contributed $500,000 to finance an anticommunist lobbying campaign headed by John T. (Terry) Dolan, chairman of the National Conservative Political Action Committee (NCPAC)." In 1986, CAUSA International sponsored the documentary film ''