Crystal Palace Fire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Crystal Palace was a

The huge, modular, iron, wood and glass, structure was originally erected in Hyde Park in London to house the

The huge, modular, iron, wood and glass, structure was originally erected in Hyde Park in London to house the  At this point, renowned gardener

At this point, renowned gardener

–

Paxton's modular, hierarchical design reflected his practical brilliance as a designer and problem-solver. It incorporated many breakthroughs, offered practical advantages that no conventional building of that era could match and, above all, it embodied the spirit of British innovation and industrial might that the Great Exhibition was intended to celebrate.

The geometry of the Crystal Palace was a classic example of the concept of form following manufacturer's limitations: the shape and size of the whole building was directly based around the size of the panes of glass made by the supplier,

Paxton's modular, hierarchical design reflected his practical brilliance as a designer and problem-solver. It incorporated many breakthroughs, offered practical advantages that no conventional building of that era could match and, above all, it embodied the spirit of British innovation and industrial might that the Great Exhibition was intended to celebrate.

The geometry of the Crystal Palace was a classic example of the concept of form following manufacturer's limitations: the shape and size of the whole building was directly based around the size of the panes of glass made by the supplier,  Paxton's roofing system incorporated his elegant solution to the problem of draining the building's vast roof area. Like the Chatsworth Lily House (but different to its later incarnation at Sydenham Hill), most of the roof of the original Hyde Park structure had a horizontal profile, so heavy rain posed a potentially serious safety hazard. Because normal cast glass is brittle and has low tensile strength, there was a risk that the weight of any excess water build-up on the roof might have caused panes to shatter, showering shards of glass onto the patrons, ruining the valuable exhibits beneath, and weakening the structure.

Paxton's ridge-and-furrow roof was designed to shed water very effectively. Rain ran off the angled glass roof panes into U-shaped timber channels which ran the length of each roof section at the bottom of the 'furrow'. These channels were ingeniously multifunctional. During construction, they served as the rails that supported and guided the trolleys on which the glaziers sat as they installed the roofing. Once completed, the channels acted both as the joists that supported the roof sections, and as guttering—a patented design now widely known as a " Paxton gutter".

These gutters conducted the rainwater to the ends of each furrow, where they emptied into the larger main gutters, which were set at right angles to the smaller gutters, along the top of the main horizontal roof beams. These main gutters drained at either end into the cast iron columns, which also had an ingenious dual function: each was cast with a hollow core, allowing it to double as a concealed down-pipe that carried the storm-water down into the drains beneath the building. One of the few issues Paxton could not completely solve was leaks—when completed, rain was found to be leaking into the huge building in over a thousand places. The leaks were sealed with putty, but the relatively poor quality of the sealant materials available at that time meant that the problem was never totally overcome.

Paxton's roofing system incorporated his elegant solution to the problem of draining the building's vast roof area. Like the Chatsworth Lily House (but different to its later incarnation at Sydenham Hill), most of the roof of the original Hyde Park structure had a horizontal profile, so heavy rain posed a potentially serious safety hazard. Because normal cast glass is brittle and has low tensile strength, there was a risk that the weight of any excess water build-up on the roof might have caused panes to shatter, showering shards of glass onto the patrons, ruining the valuable exhibits beneath, and weakening the structure.

Paxton's ridge-and-furrow roof was designed to shed water very effectively. Rain ran off the angled glass roof panes into U-shaped timber channels which ran the length of each roof section at the bottom of the 'furrow'. These channels were ingeniously multifunctional. During construction, they served as the rails that supported and guided the trolleys on which the glaziers sat as they installed the roofing. Once completed, the channels acted both as the joists that supported the roof sections, and as guttering—a patented design now widely known as a " Paxton gutter".

These gutters conducted the rainwater to the ends of each furrow, where they emptied into the larger main gutters, which were set at right angles to the smaller gutters, along the top of the main horizontal roof beams. These main gutters drained at either end into the cast iron columns, which also had an ingenious dual function: each was cast with a hollow core, allowing it to double as a concealed down-pipe that carried the storm-water down into the drains beneath the building. One of the few issues Paxton could not completely solve was leaks—when completed, rain was found to be leaking into the huge building in over a thousand places. The leaks were sealed with putty, but the relatively poor quality of the sealant materials available at that time meant that the problem was never totally overcome.

To maintain a comfortable temperature inside such a large glass building was another major challenge, because the Great Exhibition took place decades before the introduction of electricity and air-conditioning. Glasshouses rely on the fact that they accumulate and retain heat from the sun, but such heat buildup would have been a major problem for the exhibition. This would have been exacerbated by the heat produced by the thousands of people who would be in the building at any given time. Paxton solved this with two clever strategies. One was to install external canvas shade-cloths that were stretched across the roof ridges. These served multiple functions: they reduced heat transmission, moderated and softened the light coming into the building, and acted as a primitive evaporative cooling system when water was sprayed onto them. The other part of the solution was Paxton's ingenious ventilation system. Each of the modules that formed the outer walls of the building was fitted with a prefabricated set of louvres that could be opened and closed using a gear mechanism, allowing hot stale air to escape. The flooring consisted of boards wide which were spaced about apart; together with the louvres, this formed an effective passive air-conditioning system. Because of the pressure differential, the hot air escaping from the louvres generated a constant airflow that drew cooler air up through the gaps in the floor.

The floor too had a dual function: the gaps between the boards acted as a grating that allowed dust and small pieces of refuse to fall or be swept through them onto the ground beneath, where it was collected daily by a team of cleaning boys. Paxton also designed machines to sweep the floors at the end of each day. But in practice, it was found that the trailing skirts of the female visitors did the job well.

Thanks to the considerable economies of scale Paxton was able to exploit, the manufacture and assembly of the building parts was exceedingly quick and cheap. Each module was identical, fully prefabricated, self-supporting, and fast and easy to erect. All of the parts could be mass-produced in large numbers, and many parts served multiple functions, further reducing both the number of parts needed and their overall cost. Because of its comparatively low weight, the Crystal Palace required no heavy masonry for supporting walls or foundations. The relatively light concrete footings on which it stood could be left in the ground once the building was removed (they remain in place today just beneath the surface of the site). The modules could be erected as quickly as the parts could reach the site—some sections were standing within eighteen hours of leaving the factory—and since each unit was self-supporting, workers were able to assemble much of the building section-by-section, without having to wait for other parts to be finished.

To maintain a comfortable temperature inside such a large glass building was another major challenge, because the Great Exhibition took place decades before the introduction of electricity and air-conditioning. Glasshouses rely on the fact that they accumulate and retain heat from the sun, but such heat buildup would have been a major problem for the exhibition. This would have been exacerbated by the heat produced by the thousands of people who would be in the building at any given time. Paxton solved this with two clever strategies. One was to install external canvas shade-cloths that were stretched across the roof ridges. These served multiple functions: they reduced heat transmission, moderated and softened the light coming into the building, and acted as a primitive evaporative cooling system when water was sprayed onto them. The other part of the solution was Paxton's ingenious ventilation system. Each of the modules that formed the outer walls of the building was fitted with a prefabricated set of louvres that could be opened and closed using a gear mechanism, allowing hot stale air to escape. The flooring consisted of boards wide which were spaced about apart; together with the louvres, this formed an effective passive air-conditioning system. Because of the pressure differential, the hot air escaping from the louvres generated a constant airflow that drew cooler air up through the gaps in the floor.

The floor too had a dual function: the gaps between the boards acted as a grating that allowed dust and small pieces of refuse to fall or be swept through them onto the ground beneath, where it was collected daily by a team of cleaning boys. Paxton also designed machines to sweep the floors at the end of each day. But in practice, it was found that the trailing skirts of the female visitors did the job well.

Thanks to the considerable economies of scale Paxton was able to exploit, the manufacture and assembly of the building parts was exceedingly quick and cheap. Each module was identical, fully prefabricated, self-supporting, and fast and easy to erect. All of the parts could be mass-produced in large numbers, and many parts served multiple functions, further reducing both the number of parts needed and their overall cost. Because of its comparatively low weight, the Crystal Palace required no heavy masonry for supporting walls or foundations. The relatively light concrete footings on which it stood could be left in the ground once the building was removed (they remain in place today just beneath the surface of the site). The modules could be erected as quickly as the parts could reach the site—some sections were standing within eighteen hours of leaving the factory—and since each unit was self-supporting, workers were able to assemble much of the building section-by-section, without having to wait for other parts to be finished.

Fox, Henderson and Co took possession of the site in July 1850, and erected wooden hoardings which were constructed using the timber that later became the floorboards of the finished building. More than 5,000

Fox, Henderson and Co took possession of the site in July 1850, and erected wooden hoardings which were constructed using the timber that later became the floorboards of the finished building. More than 5,000  The last major components to be put into place were the 16 semi-circular ribs of the vaulted transept, which were the only major structural parts that were made of wood. These were raised into position as eight pairs, and all were fixed into place within a week. Thanks to the simplicity of Paxton's design and the combined efficiency of the building contractor and their suppliers, the entire structure was assembled with extraordinary speed: a team of 80 men could fix more than 18,000 panes of sheet glass in a week, and the building was completed and ready to receive exhibits in just five months.

According to a study by John Gardner of

The last major components to be put into place were the 16 semi-circular ribs of the vaulted transept, which were the only major structural parts that were made of wood. These were raised into position as eight pairs, and all were fixed into place within a week. Thanks to the simplicity of Paxton's design and the combined efficiency of the building contractor and their suppliers, the entire structure was assembled with extraordinary speed: a team of 80 men could fix more than 18,000 panes of sheet glass in a week, and the building was completed and ready to receive exhibits in just five months.

According to a study by John Gardner of  Paxton was acclaimed worldwide for his achievement and was knighted by Queen Victoria in recognition of his work. The project was engineered by

Paxton was acclaimed worldwide for his achievement and was knighted by Queen Victoria in recognition of his work. The project was engineered by

The

The

File:1851 Medal Crystal Palace World Expo London, obverse.jpg, 1851 medal The Crystal Palace in London by Allen & Moore, obverse

File:1851 Medal Crystal Palace World Expo London, reverse.jpg, 1851 medal The Crystal Palace in London by Allen & Moore, reverse

Dozens of experts such as

Dozens of experts such as  The centre transept once housed a circus and was the scene of daring feats by acts such as the tightrope walker

The centre transept once housed a circus and was the scene of daring feats by acts such as the tightrope walker

The development of ground and gardens of the park cost considerably more than the rebuilt Crystal Palace. Edward Milner designed the Italian Garden and fountains, the Great Maze, and the English Landscape Garden.

The development of ground and gardens of the park cost considerably more than the rebuilt Crystal Palace. Edward Milner designed the Italian Garden and fountains, the Great Maze, and the English Landscape Garden.  Joseph Paxton was first and foremost a gardener, and his layout of gardens, fountains, terraces and waterfalls left no doubt as to his ability. One thing he did have a problem with was water supply. Such was his enthusiasm that thousands of gallons of water were needed to feed the myriad fountains and cascades abounding in the Park: the two main jets were high.

Joseph Paxton was first and foremost a gardener, and his layout of gardens, fountains, terraces and waterfalls left no doubt as to his ability. One thing he did have a problem with was water supply. Such was his enthusiasm that thousands of gallons of water were needed to feed the myriad fountains and cascades abounding in the Park: the two main jets were high.

By the 1890s, the Palace's popularity and state of repair had deteriorated; the appearance of stalls and booths had made it a much more downmarket attraction.

In the years after the Festival of Empire the building fell into disrepair, as the huge debt and maintenance costs became unsustainable, and in 1911, bankruptcy was declared.

By the 1890s, the Palace's popularity and state of repair had deteriorated; the appearance of stalls and booths had made it a much more downmarket attraction.

In the years after the Festival of Empire the building fell into disrepair, as the huge debt and maintenance costs became unsustainable, and in 1911, bankruptcy was declared.

On the evening of 30 November 1936, Sir Henry Buckland was walking his dog near the Palace with his daughter Crystal, named after the building, when they noticed a red glow within it. When Buckland went inside, he found two of his employees fighting a small office fire that had started after an explosion in the women's

On the evening of 30 November 1936, Sir Henry Buckland was walking his dog near the Palace with his daughter Crystal, named after the building, when they noticed a red glow within it. When Buckland went inside, he found two of his employees fighting a small office fire that had started after an explosion in the women's

The north tower was demolished with explosives in 1941. No reason was given for its removal—it was rumoured that it was to remove a landmark for German aircraft in the Second World War. In fact

The north tower was demolished with explosives in 1941. No reason was given for its removal—it was rumoured that it was to remove a landmark for German aircraft in the Second World War. In fact

Official website

of the Crystal Palace Foundation

Crystal Palace Museum

The Crystal Palace

on ArchDaily

Crystal Palace: from metallic lattice to portal frame

by Isaac Rodrigo López César -

Park hosts Crystal Palace replica

–

Historic images of Crystal Palace, dating back to the 1850s

Taken by Philip Delamotte but now held by the

The Crystal Palace, sources from www.victorianlondon.org

* Crystal Palace - 3D version

Rendered images

an

Video

A 3D computer model of the Crystal Palace with images and animation

Maps

– map of the park as was until recently * including Victorian maps showing the palace Baird Television

, Russell A. Potter, Ph.D., Associate Professor of English,

Crystal Palace Television Studios

- Bairdtelevision.com Ray Herbert's article (1998) about the Baird Television studios {{DEFAULTSORT:Crystal Palace, The 1851 establishments in England 1936 disestablishments in England Buildings and structures completed in 1851 Buildings and structures demolished in 1936 Building and structure fires in London 1930s fires in the United Kingdom 1936 fires 1936 disasters in the United Kingdom History of the London Borough of Bromley Cultural and educational buildings in London Crystal Palace, London Former buildings and structures in the London Borough of Bromley Former buildings and structures in the City of Westminster Demolished buildings and structures in London Parks and open spaces in the London Borough of Bromley Palaces in London Greenhouses in the United Kingdom World's fair architecture in London Relocated buildings and structures in England Burned buildings and structures in the United Kingdom Cast-iron architecture in the United Kingdom Great Exhibition Joseph Paxton buildings and structures

cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

and plate glass

Plate glass, flat glass or sheet glass is a type of glass, initially produced in plane form, commonly used for windows, glass doors, transparent walls, and windscreens. For modern architectural and automotive applications, the flat glass is ...

structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its exhibition space to display examples of technology developed in the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

. Designed by Joseph Paxton

Sir Joseph Paxton (3 August 1803 – 8 June 1865) was an English gardener, architect, engineer and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Member of Parliament. He is best known for designing the Crystal Palace, which was built in Hyde Park, London, Hyde ...

, the Great Exhibition building was long, with an interior height of , and was three times the size of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

.

The 293,000 panes of glass were manufactured by the Chance Brothers

Chance Brothers and Company was an English glassworks originally based in Spon Lane, Smethwick, West Midlands (county), West Midlands (formerly in Staffordshire), in England. It was a leading glass manufacturer and a pioneer of British glassma ...

. The 990,000-square-foot building with its 128-foot-high ceiling was completed in thirty-nine weeks. The Crystal Palace boasted the greatest area of glass ever seen in a building. It astonished visitors with its clear walls and ceilings that did not require interior lights.

It has been suggested that the name of the building resulted from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold

Douglas William Jerrold (3 January 18038 June 1857) was an English dramatist and writer.

Early life

Jerrold's father, Samuel Jerrold, was an actor and lessee of the little theatre of Wilsby near Cranbrook, Kent. In 1807 the family moved to Sh ...

, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine '' Punch'' about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a "palace of very crystal".

After the exhibition, the Palace was relocated to an open area of South London

South London is the southern part of Greater London, England, south of the River Thames. The region consists of the Districts of England, boroughs, in whole or in part, of London Borough of Bexley, Bexley, London Borough of Bromley, Bromley, Lon ...

known as Penge Place which had been excised from Penge Common

Penge Common was an area of north east Surrey and north west Kent which now forms part of London, England; covering most of Penge, all of Anerley, and parts of surrounding suburbs including South Norwood. It abutted the Great North Wood and John ...

. It was rebuilt at the top of Penge Peak next to Sydenham Hill

Sydenham Hill forms part of Norwood Ridge, a longer ridge and is an affluent Human settlement, locality in southeast London. It is also the name of a road which runs along the northeastern part of the ridge, demarcating the London Boroughs of ...

, an affluent suburb of large villas. It stood there from June 1854 until its destruction by fire in November 1936. The nearby residential area was renamed Crystal Palace

Crystal Palace may refer to:

Places Canada

* Crystal Palace Complex (Dieppe), a former amusement park now a shopping complex in Dieppe, New Brunswick

* Crystal Palace Barracks, London, Ontario

* Crystal Palace (Montreal), an exhibition buildin ...

after the landmark. This included the Crystal Palace Park

Crystal Palace Park is a park in south-east London, Grade II* listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens. It was laid out in the 1850s as a pleasure ground, centred around the re-location of The Crystal Palace – the largest glass ...

that surrounds the site, home of the Crystal Palace National Sports Centre

The National Sports Centre at Crystal Palace, London, Crystal Palace in south London, England is a large sports centre and outdoor Sport of athletics, athletics stadium. It was opened in 1964 in Crystal Palace Park, close to the site of the for ...

, which was previously a football stadium that hosted the FA Cup Final

The FA Cup Final is the last match in the FA Cup, Football Association Challenge Cup. It has regularly been one of the List of sports attendance figures, most attended domestic football events in the world, with an official attendance of 89,472 ...

between 1895 and 1914. Crystal Palace F.C.

Crystal Palace Football Club, commonly referred to as Crystal Palace or simply Palace, is a professional football club based in Selhurst, South London, England, which competes in the Premier League, the top-tier of English football. The clu ...

were founded at the site and played at the Cup Final venue in their early years. The park still contains Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (8 February 1807 – 27 January 1894) was an English sculptor and natural history artist renowned for his work on the life-size models of dinosaurs in the Crystal Palace Park in south London. The models, accurately ...

's Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs are a series of sculptures of dinosaurs and other extinct animals in the London borough of Bromley's Crystal Palace Park. Commissioned in 1852 to accompany the Crystal Palace after its move from the Great Exhi ...

which date back to 1854.

Original Hyde Park building

Conception

The huge, modular, iron, wood and glass, structure was originally erected in Hyde Park in London to house the

The huge, modular, iron, wood and glass, structure was originally erected in Hyde Park in London to house the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

of 1851, which showcased the products of many countries throughout the world. The commission in charge of mounting the Great Exhibition was established in January 1850, and it was decided at the outset that the entire project would be funded by public subscription. An executive building committee was quickly formed to oversee the design and construction of the exhibition building, comprising accomplished engineers Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel ( ; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history", "one of the 19th-century engi ...

and Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson , (honoris causa, Hon. causa) (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railways", he built on the achievements of hi ...

, renowned architects Charles Barry

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was an English architect best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also responsi ...

and Thomas Leverton Donaldson

Thomas Leverton Donaldson (19 October 1795 – 1 August 1885) was a British architect, notable as a pioneer in architectural education, as a co-founder and President of the Royal Institute of British Architects and a winner of the RIBA Royal Gol ...

, and chaired by William Cubitt

Sir William Cubitt FRS (bapt. 9 October 1785 – 13 October 1861) was an English civil engineer and millwright. Born in Norfolk, England, he was employed in many of the great engineering undertakings of his time. He invented a type of windmil ...

. By 15 March 1850 they were ready to invite submissions which had to conform to several key specifications: the building had to be temporary, simple, as cheap as possible, and economical to build within the short time remaining before the exhibition opening, which had already been scheduled for 1 May 1851.Kate Colquhoun, ''A Thing in Disguise: The Visionary Life of Joseph Paxton'' (HarperCollins

HarperCollins Publishers LLC is a British–American publishing company that is considered to be one of the "Big Five (publishers), Big Five" English-language publishers, along with Penguin Random House, Hachette Book Group USA, Hachette, Macmi ...

, 2004), Ch. 16

Within three weeks, the committee had received some 245 entries, including 38 international submissions from Australia, the Netherlands, Belgium, Hanover

Hanover ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the States of Germany, German state of Lower Saxony. Its population of 535,932 (2021) makes it the List of cities in Germany by population, 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-l ...

, Switzerland, Brunswick, Hamburg and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. Two designs, both in iron and glass, were singled out for praise—one by Richard Turner, co-designer of the Palm House, Kew Gardens

The Palm House is a large palm house in the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, in London, that specialises in growing arecaceae, palms and other tropical and subtropical plants. It was completed in 1848. Many of its plants are endangered or extinct in ...

, and the other by French architect Hector Horeau but despite the great number of submissions, the committee rejected them all. Turner was furious at the rejection and reportedly badgered the commissioners for months afterwards, seeking compensation, but at an estimated £300,000, his design (like Horeau's) was too expensive.

As a last resort, the committee came up with a standby design of its own, for a brick building in the ''rundbogenstil

(round-arch style) is a 19th-century historic revival style of architecture popular in the German-speaking lands and the German diaspora. It combines elements of Byzantine, Romanesque, and Renaissance architecture with particular s ...

'' (round-arch style) by Donaldson, featuring a sheet-iron dome designed by Tunnel, but it was widely criticized and ridiculed when it was published in the newspapers. Adding to the committee's woes, the site for the exhibition was still not confirmed. The preferred site was in Hyde Park, adjacent to Princes Gate near Pennington Road, but other sites considered included Wormwood Scrubs

Wormwood Scrubs, known locally as The Scrubs (or simply Scrubs), is an open space in Old Oak Common located in the north-eastern corner of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in west London. It is the largest open space in the borough ...

, Battersea Park

Battersea Park is a 200-acre (83-hectare) green space at Battersea in the London Borough of Wandsworth in London. It is situated on the south bank of the River Thames opposite Chelsea, London, Chelsea and was opened in 1858.

The park occupies ...

, the Isle of Dogs

The Isle of Dogs is a large peninsula bounded on three sides by a large meander in the River Thames in East London, England. It includes the Cubitt Town, Millwall and Canary Wharf districts. The area was historically part of the Manor, Haml ...

, Victoria Park, and Regent's Park

Regent's Park (officially The Regent's Park) is one of the Royal Parks of London. It occupies in north-west Inner London, administratively split between the City of Westminster and the London Borough of Camden, Borough of Camden (and historical ...

.

Opponents of the scheme lobbied strenuously against the use of Hyde Park (and they were strongly supported by ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

''). The most outspoken critic was Charles Sibthorp

Charles de Laet Waldo Sibthorp (14 February 1783 – 14 December 1855), popularly known as Colonel Sibthorp, was a widely caricatured British Ultra-Tory politician in the early 19th century. He sat as a Member of Parliament for Lincoln from 182 ...

; he denounced the exhibition as "one of the greatest humbugs, frauds and absurdities ever known," and his trenchant opposition to both the exhibition and its building continued even after it had closed.

At this point, renowned gardener

At this point, renowned gardener Joseph Paxton

Sir Joseph Paxton (3 August 1803 – 8 June 1865) was an English gardener, architect, engineer and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Member of Parliament. He is best known for designing the Crystal Palace, which was built in Hyde Park, London, Hyde ...

became interested in the project, and with the enthusiastic backing of commission member Henry Cole Henry Cole may refer to:

*Sir Henry Cole (inventor)

Sir Henry Cole FRSA (15 July 1808 – 15 April 1882) was an English civil servant and inventor who facilitated many innovations in commerce, education and the arts in the 19th century in the ...

, he decided to submit his own design. At this time, Paxton was chiefly known for his celebrated career as the head gardener for the Duke of Devonshire

Duke of Devonshire is a title in the Peerage of England held by members of the Cavendish family. This (now the senior) branch of the Cavendish family has been one of the wealthiest British aristocratic families since the 16th century and has b ...

at Chatsworth House

Chatsworth House is a stately home in the Derbyshire Dales, north-east of Bakewell and west of Chesterfield, Derbyshire, Chesterfield, England. The seat of the Duke of Devonshire, it has belonged to the House of Cavendish, Cavendish family si ...

. By 1850, Paxton had become a preeminent figure in British horticulture and had also earned great renown as a freelance garden designer; his works included the pioneering public gardens at Birkenhead Park

Birkenhead Park is a major public park located in the centre of Birkenhead, Merseyside, England. It was designed by Joseph Paxton and opened on 5 April 1847.

Birkenhead park was designated a conservation area in 1977 and declared a Grade I N ...

which directly influenced the design of New York's Central Park.

At Chatsworth, he had experimented extensively with glasshouse construction, developing many novel techniques for modular construction, using combinations of standard-sized sheets of glass, laminated wood

Simulated flight (using image stack created by μCT scanning) through the length of a knitting needle that consists of laminated wooden layers: the layers can be differentiated by the change of direction of the wood's vessels

Shattered windshi ...

, and prefabricated cast iron. The "Great Stove" (or conservatory) at Chatsworth (built in 1836) was the first major application of his ridge-and-furrow roof design and was at the time the largest glass building in the world, covering around .

A decade later, taking advantage of the availability of the new cast plate glass

Plate glass, flat glass or sheet glass is a type of glass, initially produced in plane form, commonly used for windows, glass doors, transparent walls, and windscreens. For modern architectural and automotive applications, the flat glass is ...

, Paxton further developed his techniques with the Chatsworth Lily House, which featured a flat-roof version of the ridge-and-furrow glazing, and a curtain wall system that allowed the hanging of vertical bays of glass from cantilevered beams. The Lily House was built specifically to house the ''Victoria amazonica

''Victoria amazonica'' is a species of flowering plant, the second largest in the water lily family Nymphaeaceae. It is called Vitória-Régia or Iaupê-Jaçanã ("the Jacanidae, jacana's waterlily") in Brazil and Atun Sisac ("great flower") in ...

'' waterlily which had recently been discovered by European botanists; the first specimen to reach England was originally kept at Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens is a botanical garden, botanic garden in southwest London that houses the "largest and most diverse botany, botanical and mycology, mycological collections in the world". Founded in 1759, from the exotic garden at Kew Park, its li ...

, but it did not do well. Paxton's reputation as a gardener was so high by that time that he was invited to take the lily to Chatsworth. It thrived under his care, and in 1849 he caused a sensation in the horticultural world when he succeeded in producing the first ''amazonica'' flowers to be grown in England. His daughter Alice was drawn for the newspapers, standing on one of the leaves. The lily and its house led directly to Paxton's design for the Crystal Palace. He later cited the huge ribbed floating leaves as a key inspiration.

Paxton left his meeting with Cole on 9 June 1850 fired with enthusiasm. He immediately went to Hyde Park, where he walked the site earmarked for the Exhibition. Two days later on 11 June, while attending a board meeting of the Midland Railway

The Midland Railway (MR) was a railway company in the United Kingdom from 1844 in rail transport, 1844. The Midland was one of the largest railway companies in Britain in the early 20th century, and the largest employer in Derby, where it had ...

, Paxton made his original concept drawing, which he doodled onto a sheet of pink blotting paper

Blotting paper is a highly absorbent type of paper used to absorb ink or oil from writing material, particularly when quills or fountain pens were popular. It could also be used in testing how much oil is present in products. Blotting paper ...

. This rough sketch (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (abbreviated V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.8 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and named after Queen ...

) incorporated all the basic features of the finished building, and it is a mark of Paxton's ingenuity and industriousness that detailed plans, calculations and costings were ready to submit in less than two weeks. (The statue of Albert, Prince Consort, in Perth, Scotland

Perth (; ) is a centrally located Cities of Scotland, Scottish city, on the banks of the River Tay. It is the administrative centre of Perth and Kinross council area and is the historic county town of Perthshire. It had a population of about ...

, was sculpted with the subject holding a plan of the Crystal Palace. The statue was unveiled by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

in 1864.Albert, Prince Consort, Statue To, North Inch–

Historic Environment Scotland

Historic Environment Scotland (HES) () is an executive non-departmental public body responsible for investigating, caring for and promoting Scotland's historic environment. HES was formed in 2015 from the merger of government agency Historic Sc ...

)

The project was a major gamble for Paxton, but circumstances were in his favour: he enjoyed a stellar reputation as a garden designer and builder, he was confident that his design was perfectly suited to the brief, and the commission was under pressure to choose a design and get it built, with the exhibition opening less than a year away. In the event, Paxton's design fulfilled and surpassed all the requirements, and it proved to be vastly faster and cheaper to build than any other form of building of a comparable size. His submission was budgeted at a remarkably low £85,800. By comparison, this was about times more than the Great Stove at Chatsworth but it was only 28% of the estimated cost of Turner's design, and it promised a building which, with a footprint of over , would cover roughly 25 times the ground area of its progenitor.

Impressed by the low bid for the construction contract submitted by the civil engineering contractor Fox, Henderson and Co

Sir Charles Fox (11 March 1810 – 11 June 1874) was an English civil engineer and contractor. His work focused on railways, railway stations and bridges.

Biography

Born in Derby in 1810, Charles Fox was the youngest of five sons of Dr. Francis ...

, the commission accepted the scheme and gave its public endorsement to Paxton's design in July 1850. He was exultant but now had less than eight months to finalize his plans, manufacture the parts and erect the building in time for the exhibition's opening, which was scheduled for 1 May 1851. Paxton was able to design and build the largest glass structure yet created, from scratch, in less than a year, and complete it on schedule and on budget.

He was even able to alter the design shortly before building began, adding a high, barrel-vaulted transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform ("cross-shaped") cruciform plan, churches, in particular within the Romanesque architecture, Romanesque a ...

across the centre of the building, at 90 degrees to the main gallery, under which he was able to safely enclose several large elm trees that would otherwise have had to be felled—thereby also resolving a controversial issue that had been a major sticking point for the vocal anti-exhibition lobby.

Design

Paxton's modular, hierarchical design reflected his practical brilliance as a designer and problem-solver. It incorporated many breakthroughs, offered practical advantages that no conventional building of that era could match and, above all, it embodied the spirit of British innovation and industrial might that the Great Exhibition was intended to celebrate.

The geometry of the Crystal Palace was a classic example of the concept of form following manufacturer's limitations: the shape and size of the whole building was directly based around the size of the panes of glass made by the supplier,

Paxton's modular, hierarchical design reflected his practical brilliance as a designer and problem-solver. It incorporated many breakthroughs, offered practical advantages that no conventional building of that era could match and, above all, it embodied the spirit of British innovation and industrial might that the Great Exhibition was intended to celebrate.

The geometry of the Crystal Palace was a classic example of the concept of form following manufacturer's limitations: the shape and size of the whole building was directly based around the size of the panes of glass made by the supplier, Chance Brothers

Chance Brothers and Company was an English glassworks originally based in Spon Lane, Smethwick, West Midlands (county), West Midlands (formerly in Staffordshire), in England. It was a leading glass manufacturer and a pioneer of British glassma ...

of Smethwick

Smethwick () is an industrial town in the Sandwell district, in the county of the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. It lies west of Birmingham city centre. Historically it was in Staffordshire and then Worcestershire before bei ...

. These were the largest available at the time, measuring wide by long. Because the entire building was scaled around those dimensions, it meant that nearly the whole outer surface could be glazed using hundreds of thousands of identical panes, thereby drastically reducing both their production cost and the time needed to install them.

The original Hyde Park building was essentially a vast, flat-roofed rectangular hall. A huge open gallery ran along the main axis, with wings extending down either side. The main exhibition space was two stories high, with the upper floor stepped in from the boundary. Most of the building had a flat-profile roof, except for the central transept, which was covered by a barrel-vaulted roof that stood high at the top of the arch. Both the flat-profile sections and the arched transept roof were constructed using the key element of Paxton's design: his patented ridge-and-furrow roofing system, which had first seen use at Chatsworth. The basic roofing unit, in essence, took the form of a long triangular prism, which made it both extremely light and very strong, and meant it could be built with the minimum amount of materials.

Paxton set the dimensions of this prism by using the length of single pane of glass () as the hypotenuse

In geometry, a hypotenuse is the side of a right triangle opposite to the right angle. It is the longest side of any such triangle; the two other shorter sides of such a triangle are called '' catheti'' or ''legs''. Every rectangle can be divided ...

of a right-angled triangle, thereby creating a triangle with a length-to-height ratio of 2.5:1, whose base (adjacent side) was long. By mirroring this triangle he obtained the gables that formed the vertical faces at either end of the prism, each of which was long. With this arrangement, Paxton could glaze the entire roof surface with identical panes that did not need to be trimmed. Paxton placed three of these by roof units side-by-side, horizontally supported by a grid of cast iron beams, which was held up on slim cast iron pillars. The resulting cube, with a floor area of by , formed the basic structural module of the building.

By multiplying these modules into a grid, the structure could be extended virtually indefinitely. In its original form, the ground level of the Crystal Palace (in plan) measured by , which equates to a grid 77 modules long by 19 modules wide. As each module was self-supporting, Paxton was able to leave out modules in some areas, creating larger square or rectangular spaces within the building to accommodate larger exhibits. On the lower level, these larger spaces were covered by the floor above, and on the upper level by longer spans of roofing, but the dimensions of these larger spaces were always multiples of the basic by grid unit.

The modules were also strong enough to be stacked vertically, enabling Paxton to add an upper floor that nearly doubled the amount of available exhibition space. The first floor galleries were double the height of the ground floor galleries below, and the Crystal Palace could theoretically have accommodated a full second-floor gallery, but this space was left open. Paxton also used longer trellis girders to create a clear span for the roof of the immense central gallery, which was wide and long.

Paxton's roofing system incorporated his elegant solution to the problem of draining the building's vast roof area. Like the Chatsworth Lily House (but different to its later incarnation at Sydenham Hill), most of the roof of the original Hyde Park structure had a horizontal profile, so heavy rain posed a potentially serious safety hazard. Because normal cast glass is brittle and has low tensile strength, there was a risk that the weight of any excess water build-up on the roof might have caused panes to shatter, showering shards of glass onto the patrons, ruining the valuable exhibits beneath, and weakening the structure.

Paxton's ridge-and-furrow roof was designed to shed water very effectively. Rain ran off the angled glass roof panes into U-shaped timber channels which ran the length of each roof section at the bottom of the 'furrow'. These channels were ingeniously multifunctional. During construction, they served as the rails that supported and guided the trolleys on which the glaziers sat as they installed the roofing. Once completed, the channels acted both as the joists that supported the roof sections, and as guttering—a patented design now widely known as a " Paxton gutter".

These gutters conducted the rainwater to the ends of each furrow, where they emptied into the larger main gutters, which were set at right angles to the smaller gutters, along the top of the main horizontal roof beams. These main gutters drained at either end into the cast iron columns, which also had an ingenious dual function: each was cast with a hollow core, allowing it to double as a concealed down-pipe that carried the storm-water down into the drains beneath the building. One of the few issues Paxton could not completely solve was leaks—when completed, rain was found to be leaking into the huge building in over a thousand places. The leaks were sealed with putty, but the relatively poor quality of the sealant materials available at that time meant that the problem was never totally overcome.

Paxton's roofing system incorporated his elegant solution to the problem of draining the building's vast roof area. Like the Chatsworth Lily House (but different to its later incarnation at Sydenham Hill), most of the roof of the original Hyde Park structure had a horizontal profile, so heavy rain posed a potentially serious safety hazard. Because normal cast glass is brittle and has low tensile strength, there was a risk that the weight of any excess water build-up on the roof might have caused panes to shatter, showering shards of glass onto the patrons, ruining the valuable exhibits beneath, and weakening the structure.

Paxton's ridge-and-furrow roof was designed to shed water very effectively. Rain ran off the angled glass roof panes into U-shaped timber channels which ran the length of each roof section at the bottom of the 'furrow'. These channels were ingeniously multifunctional. During construction, they served as the rails that supported and guided the trolleys on which the glaziers sat as they installed the roofing. Once completed, the channels acted both as the joists that supported the roof sections, and as guttering—a patented design now widely known as a " Paxton gutter".

These gutters conducted the rainwater to the ends of each furrow, where they emptied into the larger main gutters, which were set at right angles to the smaller gutters, along the top of the main horizontal roof beams. These main gutters drained at either end into the cast iron columns, which also had an ingenious dual function: each was cast with a hollow core, allowing it to double as a concealed down-pipe that carried the storm-water down into the drains beneath the building. One of the few issues Paxton could not completely solve was leaks—when completed, rain was found to be leaking into the huge building in over a thousand places. The leaks were sealed with putty, but the relatively poor quality of the sealant materials available at that time meant that the problem was never totally overcome.

To maintain a comfortable temperature inside such a large glass building was another major challenge, because the Great Exhibition took place decades before the introduction of electricity and air-conditioning. Glasshouses rely on the fact that they accumulate and retain heat from the sun, but such heat buildup would have been a major problem for the exhibition. This would have been exacerbated by the heat produced by the thousands of people who would be in the building at any given time. Paxton solved this with two clever strategies. One was to install external canvas shade-cloths that were stretched across the roof ridges. These served multiple functions: they reduced heat transmission, moderated and softened the light coming into the building, and acted as a primitive evaporative cooling system when water was sprayed onto them. The other part of the solution was Paxton's ingenious ventilation system. Each of the modules that formed the outer walls of the building was fitted with a prefabricated set of louvres that could be opened and closed using a gear mechanism, allowing hot stale air to escape. The flooring consisted of boards wide which were spaced about apart; together with the louvres, this formed an effective passive air-conditioning system. Because of the pressure differential, the hot air escaping from the louvres generated a constant airflow that drew cooler air up through the gaps in the floor.

The floor too had a dual function: the gaps between the boards acted as a grating that allowed dust and small pieces of refuse to fall or be swept through them onto the ground beneath, where it was collected daily by a team of cleaning boys. Paxton also designed machines to sweep the floors at the end of each day. But in practice, it was found that the trailing skirts of the female visitors did the job well.

Thanks to the considerable economies of scale Paxton was able to exploit, the manufacture and assembly of the building parts was exceedingly quick and cheap. Each module was identical, fully prefabricated, self-supporting, and fast and easy to erect. All of the parts could be mass-produced in large numbers, and many parts served multiple functions, further reducing both the number of parts needed and their overall cost. Because of its comparatively low weight, the Crystal Palace required no heavy masonry for supporting walls or foundations. The relatively light concrete footings on which it stood could be left in the ground once the building was removed (they remain in place today just beneath the surface of the site). The modules could be erected as quickly as the parts could reach the site—some sections were standing within eighteen hours of leaving the factory—and since each unit was self-supporting, workers were able to assemble much of the building section-by-section, without having to wait for other parts to be finished.

To maintain a comfortable temperature inside such a large glass building was another major challenge, because the Great Exhibition took place decades before the introduction of electricity and air-conditioning. Glasshouses rely on the fact that they accumulate and retain heat from the sun, but such heat buildup would have been a major problem for the exhibition. This would have been exacerbated by the heat produced by the thousands of people who would be in the building at any given time. Paxton solved this with two clever strategies. One was to install external canvas shade-cloths that were stretched across the roof ridges. These served multiple functions: they reduced heat transmission, moderated and softened the light coming into the building, and acted as a primitive evaporative cooling system when water was sprayed onto them. The other part of the solution was Paxton's ingenious ventilation system. Each of the modules that formed the outer walls of the building was fitted with a prefabricated set of louvres that could be opened and closed using a gear mechanism, allowing hot stale air to escape. The flooring consisted of boards wide which were spaced about apart; together with the louvres, this formed an effective passive air-conditioning system. Because of the pressure differential, the hot air escaping from the louvres generated a constant airflow that drew cooler air up through the gaps in the floor.

The floor too had a dual function: the gaps between the boards acted as a grating that allowed dust and small pieces of refuse to fall or be swept through them onto the ground beneath, where it was collected daily by a team of cleaning boys. Paxton also designed machines to sweep the floors at the end of each day. But in practice, it was found that the trailing skirts of the female visitors did the job well.

Thanks to the considerable economies of scale Paxton was able to exploit, the manufacture and assembly of the building parts was exceedingly quick and cheap. Each module was identical, fully prefabricated, self-supporting, and fast and easy to erect. All of the parts could be mass-produced in large numbers, and many parts served multiple functions, further reducing both the number of parts needed and their overall cost. Because of its comparatively low weight, the Crystal Palace required no heavy masonry for supporting walls or foundations. The relatively light concrete footings on which it stood could be left in the ground once the building was removed (they remain in place today just beneath the surface of the site). The modules could be erected as quickly as the parts could reach the site—some sections were standing within eighteen hours of leaving the factory—and since each unit was self-supporting, workers were able to assemble much of the building section-by-section, without having to wait for other parts to be finished.

Construction

Fox, Henderson and Co took possession of the site in July 1850, and erected wooden hoardings which were constructed using the timber that later became the floorboards of the finished building. More than 5,000

Fox, Henderson and Co took possession of the site in July 1850, and erected wooden hoardings which were constructed using the timber that later became the floorboards of the finished building. More than 5,000 navvies

Navvy, a clipping of navigator ( UK) or navigational engineer ( US), is particularly applied to describe the manual labourers working on major civil engineering projects and occasionally in North America to refer to mechanical shovels and eart ...

worked on the building during its construction, with up to 2,000 on site at one time during the peak building phase. More than 1,000 iron columns supported 2,224 trellis girders and 30 miles of guttering, comprising 4,000 tons of iron in all.

Firstly stakes were driven into the ground to roughly mark out the positions for the cast iron columns; these points were then set precisely by theodolite

A theodolite () is a precision optical instrument for measuring angles between designated visible points in the horizontal and vertical planes. The traditional use has been for land surveying, but it is also used extensively for building and ...

measurements. Then the concrete foundations were poured, and the base plates for the columns were set into them. Once the foundations were in place, the erection of the modules proceeded rapidly. Connector brackets were attached to the top of each column before erection, and these were then hoisted into position.

The project took place before the development of powered cranes; the raising of the columns was done manually using shear legs

Shear legs, also known as sheers, shears, or sheer legs, are a form of two-legged lifting device. Shear legs may be permanent, formed of a solid A-frame and supports, as commonly seen on land and the floating sheerleg, or temporary, as aboard a ...

(or shears), a simple crane mechanism. These consisted of two strong poles which were set several meters apart at the base and then lashed together at the top to form a triangle; this was stabilized and kept vertical by guy ropes fixed to the apex, stretched taut and tied to stakes driven into the ground some distance away. Using pulleys and ropes hung from the apex of the shear, the navvies hoisted the columns, girders and other parts into place.

As soon as two adjacent columns had been erected, a girder was hoisted into place between them and bolted onto the connectors. The columns were erected in opposite pairs, then two more girders were connected to form a self-supporting square—this was the basic frame of each module. The shears would then be moved along and an adjoining bay constructed. When a reasonable number of bays had been completed, the columns for the upper floor were erected (longer shear-legs were used for this, but the operation was essentially the same as for the ground floor). Once the ground floor structure was complete, the final assembly of the upper floor followed rapidly.

For the glazing, Paxton used larger versions of machines he had originally devised for the Great Stove at Chatsworth, installing on-site production line

A production line is a set of sequential operations established in a factory where components are assembled to make a finished article or where materials are put through a refining process to produce an end-product that is suitable for onward ...

systems, powered by steam engines, that dressed and finished the building parts. These included a machine that mechanically grooved the wooden window sash bars and a painting machine that automatically dipped the parts in paint and then passed them through a series of rotating brushes to remove the excess.

The last major components to be put into place were the 16 semi-circular ribs of the vaulted transept, which were the only major structural parts that were made of wood. These were raised into position as eight pairs, and all were fixed into place within a week. Thanks to the simplicity of Paxton's design and the combined efficiency of the building contractor and their suppliers, the entire structure was assembled with extraordinary speed: a team of 80 men could fix more than 18,000 panes of sheet glass in a week, and the building was completed and ready to receive exhibits in just five months.

According to a study by John Gardner of

The last major components to be put into place were the 16 semi-circular ribs of the vaulted transept, which were the only major structural parts that were made of wood. These were raised into position as eight pairs, and all were fixed into place within a week. Thanks to the simplicity of Paxton's design and the combined efficiency of the building contractor and their suppliers, the entire structure was assembled with extraordinary speed: a team of 80 men could fix more than 18,000 panes of sheet glass in a week, and the building was completed and ready to receive exhibits in just five months.

According to a study by John Gardner of Anglia Ruskin University

Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) is a public research university in the region of East Anglia, United Kingdom. Its origins date back to the Cambridge School of Art (CSA), founded by William John Beamont, a Fellow of Trinity College at the Unive ...

, published in The International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology,the speed of the erection work was thanks to the use, for the first time, of nuts and bolts made to what was later to be known as the British Standard Whitworth

British Standard Whitworth (BSW) is a screw thread standard that uses imperial-unit, imperial (inch-based) units. It was devised and specified by British engineerJoseph Whitworth in 1841, making it the world’s first national screw thread stand ...

(BSW), when up to that time nuts and bolts were made individually, and could not be interchanged.

When completed, the Crystal Palace provided an unrivalled space for exhibits, since it was essentially a self-supporting shell standing on slim iron columns, with no internal structural walls whatsoever. Because it was covered almost entirely in glass, it also needed no artificial lighting during the day, thereby reducing the exhibition's running costs.

Full-size elm trees growing in the park were enclosed within the central exhibition hall near the tall Crystal Fountain. However this caused a problem with sparrows

Sparrow may refer to:

Birds

* Old World sparrows, family Passeridae

** House sparrow, or ''Passer domesticus''

* New World sparrows, family Passerellidae

* two species in the Passerine family Estrildidae:

** Java sparrow

** Timor sparrow

* Hed ...

becoming a nuisance, and shooting was out of the question inside a glass building. Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

mentioned this problem to the Duke of Wellington

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they ar ...

, who offered the solution, " Sparrowhawks, Ma'am".

Paxton was acclaimed worldwide for his achievement and was knighted by Queen Victoria in recognition of his work. The project was engineered by

Paxton was acclaimed worldwide for his achievement and was knighted by Queen Victoria in recognition of his work. The project was engineered by William Cubitt

Sir William Cubitt FRS (bapt. 9 October 1785 – 13 October 1861) was an English civil engineer and millwright. Born in Norfolk, England, he was employed in many of the great engineering undertakings of his time. He invented a type of windmil ...

; Paxton's construction partner was the ironwork contractor Fox and Henderson, whose director Charles Fox was also knighted for his contribution. The 900,000 square feet (84,000 m2) of glass was provided by the Chance Brothers glassworks in Smethwick. This was the only glassworks capable of fulfilling such a large order; it had to bring in labour from the Saint-Gobain

Compagnie de Saint-Gobain S.A. () is a French multinational corporation, founded in 1665 in Paris as the Manufacture royale de glaces de miroirs, and today headquartered on the outskirts of Paris, at La Défense and in Courbevoie. Originally a ...

glassworks in France to fulfil the order in time. The final dimensions were long by wide. The building was high, with on the ground floor alone.

Great Exhibition

The

The Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

was opened on 1 May 1851 by Queen Victoria. It was the first of the World's fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition, is a large global exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specific site for a perio ...

exhibitions of culture and industry. There were some 100,000 objects, displayed along more than ten miles, by over 15,000 contributors. Britain occupied half the display space inside with exhibits from the home country and the empire. France was the largest foreign contributor. The exhibits were grouped into four main categories—Raw Materials, Machinery, Manufacturers and Fine Arts. The exhibits ranged from the Koh-i-Noor

The ; ), also spelled Koh-e-Noor, Kohinoor and Koh-i-Nur, is one of the largest cut diamonds in the world, weighing . It is currently set in the Crown of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother.

The diamond originated in the Kollur mine in present ...

diamond, Sèvres porcelain

Sèvres (, ) is a French Communes of France, commune in the southwestern suburbs of Paris. It is located from the Kilometre zero, centre of Paris, in the Hauts-de-Seine department of the Île-de-France region. The commune, which had a populatio ...

, and music organs to a massive hydraulic press, and a fire engine. There was also a 27-foot tall Crystal Fountain.

In the first week, the prices were £1; they were then reduced to five shillings for the next three weeks, a price which still effectively limited entrance to middle-class and aristocratic visitors. The working classes finally came to the exhibition on 26 May, when weekday prices were reduced to one shilling (although the price was two shillings and sixpence on Fridays, and still five shillings on Saturdays). Over six million admissions were counted at the toll-gates, although the proportion which were repeat/returning visitors is not known. The event made a surplus of £186,000 (equivalent to £), money which was used to found the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum

A science museum is a museum devoted primarily to science. Older science museums tended to concentrate on static displays of objects related to natural history, paleontology, geology, Industry (manufacturing), industry and Outline of industrial ...

and the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

in South Kensington

South Kensington is a district at the West End of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with the advent of the ra ...

.

The Crystal Palace had the first major installation of public toilet

A public toilet, restroom, bathroom or washroom is a room or small building with toilets (or urinals) and sinks for use by the general public. The facilities are available to customers, travelers, employees of a business, school pupils or pris ...

s, the ''Retiring Rooms'', in which sanitary engineer George Jennings

George Jennings (10 November 1810 – 17 April 1882) was an English sanitary engineer and plumber who invented the first public flush toilets. These were first showcased at the Great Exhibition in 1851, and such was the popularity of his invent ...

installed his "Monkey Closet" flushing lavatory (initially just for men but later catering for women also). During the exhibition, 827,280 visitors each paid one penny to use them. It is often suggested that the euphemism " spending a penny" originated at the exhibition, but the phrase is more likely to date from the 1890s when public lavatories, fitted with penny-coin-operated locks, were first established by British local authorities. The Great Exhibition closed on 15 October 1851.

Sydenham Hill

Relocation and redesign

The life of the Great Exhibition was limited to six months, after which something had to be decided on the future of the Crystal Palace building. Against the wishes ofparliamentary

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

opponents, a consortium of eight businessmen, including Samuel Laing and Leo Schuster, who were both board members of the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway

The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR (known also as the Brighton line, the Brighton Railway or the Brighton)) was a railway company in the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1922. Its territory formed a rough triangle, with London at ...

(LB&SCR), formed a holding company and proposed that the edifice be taken down and relocated to a property named Penge Place, which had been excised from Penge Common

Penge Common was an area of north east Surrey and north west Kent which now forms part of London, England; covering most of Penge, all of Anerley, and parts of surrounding suburbs including South Norwood. It abutted the Great North Wood and John ...

at the top of Sydenham Hill

Sydenham Hill forms part of Norwood Ridge, a longer ridge and is an affluent Human settlement, locality in southeast London. It is also the name of a road which runs along the northeastern part of the ridge, demarcating the London Boroughs of ...

.

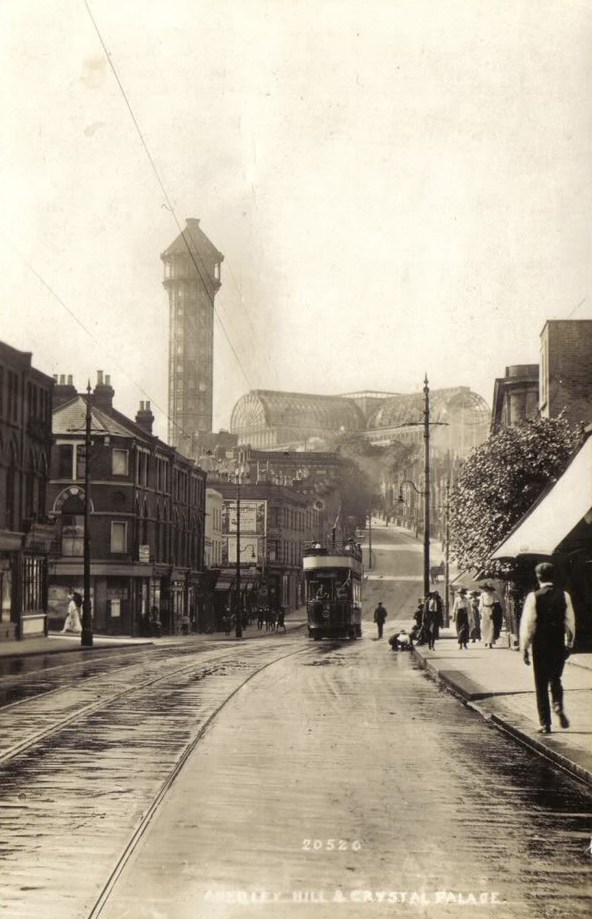

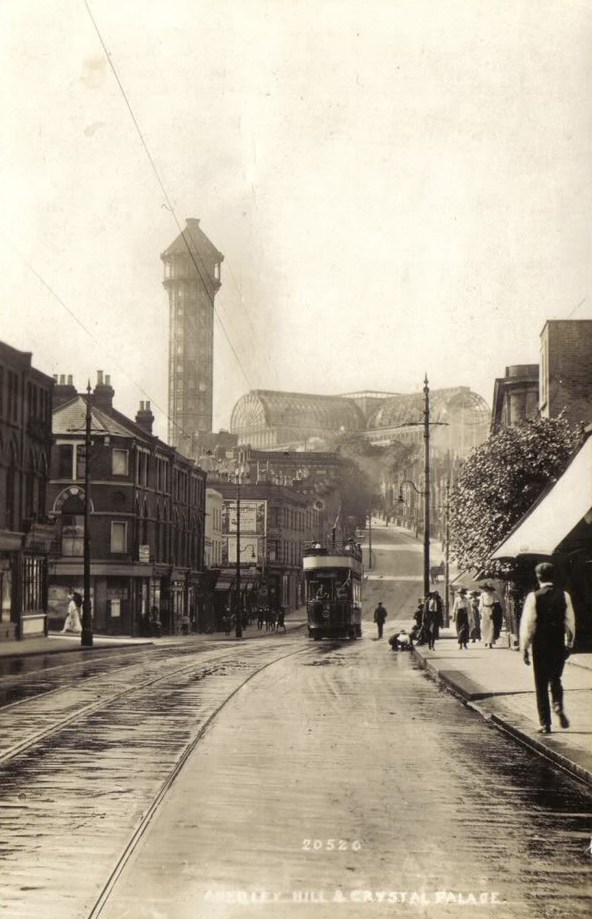

The reconstruction of the Crystal Palace began on Sydenham Hill in 1852. The new building, while incorporating most of the constructional parts of the original one at Hyde Park, was so completely different in form as to be properly considered a quite different structure – a ' Beaux-arts' form in glass and metal. The main gallery was redesigned and covered with a barrel-vaulted roof; the central transept was greatly enlarged and made even higher; the large arch of the main entrance was framed by a new facade and served by an imposing set of terraces and stairways. The building measured feet in length by feet across the transepts.

The new building was elevated several metres above the surrounding grounds, and two large transepts were added at either end of the main gallery. It was modified and enlarged so much that it extended beyond the boundary of Penge Place, which was also the boundary between Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

and Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

. The reconstruction was recorded for posterity by Philip Henry Delamotte

Philip Henry Delamotte (21 April 1821 – 24 February 1889) was a British photographer and illustrator. Life

Delamotte was born at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, the son of Mary and William Alfred Delamotte. Philip Delamotte became an ...

, and his photographs were widely disseminated in his published works. The Crystal Palace Company also commissioned Negretti and Zambra Negretti is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Ettore Negretti (1883–after 1902), Italian footballer

* Giovanna Negretti, American activist

* Henry Negretti (1818–1879) of the firm Negretti and Zambra

* Jacopo Negretti (14 ...

to produce stereographs of the interior and grounds of the building. Within two years the rebuilt Crystal Palace was complete, and on 10 June 1854, Queen Victoria again performed an opening ceremony, in the presence of 40,000 guests.

Several localities claim to be the area to which the building was moved. The street address of the Crystal Palace was Sydenham (SE26) after 1917, but the actual building and parklands were mostly in Penge with the eastern portion in Beckenham, Kent. When built, most of the buildings were in the County of Surrey, as were the majority of grounds, but in 1899 the county boundary was moved, transferring the entire site to Penge Urban District in Kent. The site is now within the Crystal Palace & Anerley Ward of the London Borough of Bromley

The London Borough of Bromley () is a London Borough, borough in London, England. It is the largest and southeasternmost borough in London, and borders the county of Kent, of which it formed part until 1965. The borough's population in the 2021 ...

.

Two railway stations were opened to serve the permanent exhibition:

* Crystal Palace High Level: developed by the London, Chatham and Dover Railway

The London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR or LC&DR) was a railway company in south-eastern England. It was created on 1 August 1859, when the East Kent Railway was given parliamentary approval to change its name. Its lines ran through Lond ...

, it was a building designed by Edward Middleton Barry

Edward Middleton Barry RA (7 June 1830 – 27 January 1880) was an English architect of the 19th century.

Biography

Edward Barry was the third son of Sir Charles Barry, born in his father's house, 27 Foley Place, London. In infancy he was ...

, from which a subway under the Parade led directly to the entrance.

* Crystal Palace Low Level: developed by the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, it is located just off Anerley Road.

The Low Level station is still in use as , while the only remains of the High Level station are the subway under the Parade with its Italian mosaic

A mosaic () is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/Mortar (masonry), mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and ...

roofing, a Grade II* listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

. The South Gate is served by Penge West railway station

Penge West is a station on the Windrush line of the London Overground, located in Penge, a district of the London Borough of Bromley in south London. It is down the line from , in Travelcard Zone 4. Additional limited peak-time National Rai ...

. For some time this station was on an atmospheric railway

An atmospheric railway uses differential air pressure to provide power for propulsion of a railway vehicle. A static power source can transmit motive power to the vehicle in this way, avoiding the necessity of carrying mobile power generating e ...

. This is often confused with a 550-metre pneumatic passenger railway which was exhibited at the Crystal Palace in 1864, which was known as the Crystal Palace pneumatic railway.

Exhibitions and events

Dozens of experts such as

Dozens of experts such as Matthew Digby Wyatt

Sir Matthew Digby Wyatt (28 July 1820 – 21 May 1877) was a British architect and art historian who became Secretary of the Great Exhibition, Surveyor of the East India Company and the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Camb ...

and Owen Jones

Owen Jones (born 8 August 1984) is a left-wing British newspaper columnist, commentator, journalist, author and political activist.

He writes a column for ''The Guardian'' and contributes to the ''New Statesman'', ''Tribune (magazine), Tribune ...

were hired to create a series of courts that provided a narrative of the history of fine art. Amongst these were Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 1812 – 14 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival architecture ...

's Mediaeval Court from the Great Exhibition, as well as courts illustrating Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...

, Alhambra

The Alhambra (, ; ) is a palace and fortress complex located in Granada, Spain. It is one of the most famous monuments of Islamic architecture and one of the best-preserved palaces of the historic Muslim world, Islamic world. Additionally, the ...

, Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

, Renaissance