Crushing (execution) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Death by crushing or pressing is a method of

A common method of death throughout South and Southeast Asia for over 4,000 years was crushing by elephants. The

A common method of death throughout South and Southeast Asia for over 4,000 years was crushing by elephants. The

The most famous case in the United Kingdom was that of

The most famous case in the United Kingdom was that of

Forfeiture in England and Colonial America

''The Proceedings of the Old Bailey,'' Reference Number: t16760823-6 (23 August 1676)

{{Capital punishment Execution methods Torture

execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in ...

that has a history during which the techniques used varied greatly from place to place, generally involving placing heavy weights upon a person with the intent to kill.

Crushing by elephant

A common method of death throughout South and Southeast Asia for over 4,000 years was crushing by elephants. The

A common method of death throughout South and Southeast Asia for over 4,000 years was crushing by elephants. The Sasanians

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranians"), was an Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, the length of the Sasanian dynasty's reign ...

, Romans, and Carthaginians

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians (and sometimes as Western Phoenicians), were a Semitic people, Semitic people who Phoenician settlement of North Africa, migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Iron ...

also used this method on occasion.

Ancient Rome

Inancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

legend, Tarpeia

In Roman legend, Tarpeia (; mid-8th century BCE), daughter of the Roman commander Spurius Tarpeius, was a Vestal Virgin who betrayed the city of Rome to the Sabines at the time of The Rape of the Sabine Women, their women's abduction for what sh ...

was a Vestal Virgin

In ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins or Vestals (, singular ) were priestesses of Vesta, virgin goddess of Rome's sacred hearth and its flame.

The Vestals were unlike any other public priesthood. They were chosen before puberty from several s ...

who betrayed the city of Rome to the Sabine

The Sabines (, , , ; ) were an Italic people who lived in the central Apennine Mountains (see Sabina) of the ancient Italian Peninsula, also inhabiting Latium north of the Anio before the founding of Rome.

The Sabines divided int ...

s in exchange for what she thought would be a reward of jewelry. She was instead crushed to death and her body cast from the Tarpeian Rock, which now bears her name.

Crushing in pre-Columbian America

Crushing is also reported from pre-Columbian America, notably in theAztec Empire

The Aztec Empire, also known as the Triple Alliance (, Help:IPA/Nahuatl, �jéːʃkaːn̥ t͡ɬaʔtoːˈlóːjaːn̥ or the Tenochca Empire, was an alliance of three Nahuas, Nahua altepetl, city-states: , , and . These three city-states rul ...

.Summerson, Henry (1983). "The Early Development of Peine Forte et Dure."''Law, Litigants, and the Legal Profession: Papers Presented to the Fourth British Legal History Conference at the University of Birmingham 10–13 July 1979'' ed E. W. Ives & A. H. Manchester, 116-125. Royal Historical Society Studies in History Series 36. London: Humanities Press.

Crushing under Mongol rule

Due to religious beliefs, it was at times viewed as better to execute prisoners without the shedding of blood. The means with which it could occur would vary.Crushing under common law

''Peine forte et dure'' (Law French

Law French () is an archaic language originally based on Anglo-Norman, but increasingly influenced by Parisian French and, later, English. It was used in the law courts of England from the 13th century. Its use continued for several centur ...

for "forceful and hard punishment") was a method of torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

formerly used in the common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

legal system, in which a defendant

In court proceedings, a defendant is a person or object who is the party either accused of committing a crime in criminal prosecution or against whom some type of civil relief is being sought in a civil case.

Terminology varies from one juris ...

who refused to plea

In law, a plea is a defendant's response to a criminal charge. A defendant may plead guilty or not guilty. Depending on jurisdiction, additional pleas may be available, including '' nolo contendere'' (no contest), no case to answer (in the ...

d ("stood mute") would be subjected to having heavier and heavier stones placed upon his or her chest until a plea was entered, or, as the weight of the stones on the chest became too great for the condemned to breathe, fatal suffocation occurred.

The common law courts originally took a very limited view of their own jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' and 'speech' or 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, the concept of jurisdiction applies at multiple level ...

. They considered themselves to lack jurisdiction over a defendant until he had voluntarily submitted to it by entering a plea seeking judgment from the court. Since a criminal justice

Criminal justice is the delivery of justice to those who have been accused of committing crimes. The criminal justice system is a series of government agencies and institutions. Goals include the rehabilitation of offenders, preventing other ...

system that tried and punished only those who volunteered for trial and punishment was practically unworkable, this was the means chosen to coerce them.

Many defendants charged with capital offences nonetheless refused to plead, since thereby they would escape forfeiture of property and their heirs would still inherit their estate; but if defendants pleaded guilty and were executed their heirs would inherit nothing, their property escheat

Escheat () is a common law doctrine that transfers the real property of a person who has died without heirs to the crown or state. It serves to ensure that property is not left in "limbo" without recognized ownership. It originally applied t ...

ing to the Crown. ''Peine forte et dure'' was abolished in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

in 1772, and the last known use of the practice was in 1741. In 1772 refusing to plead was deemed to be equivalent to pleading guilty. This was changed in 1827 to being deemed a plea of not guilty. Today in all common-law jurisdictions standing mute is treated by the courts as equivalent to a plea of not guilty.

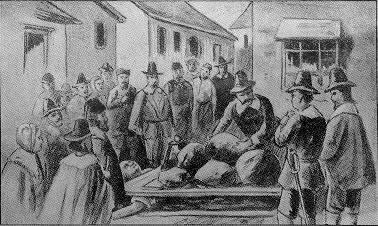

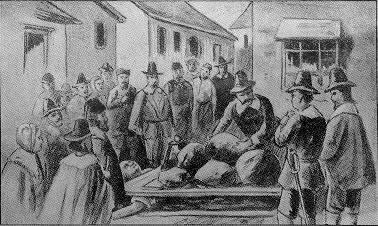

The elaborate procedure was recorded by a 15th-century witness in an oft-quoted description: "he will lie upon his back, with his head covered and his feet, and one arm will be drawn to one quarter of the house with a cord, and the other arm to another quarter, and in the same manner it will be done with his legs; and let there be laid upon his body iron and stone, as much as he can bear, or more ..."

"Pressing to death" might take several days, and not necessarily with a continued increase in the load. The Frenchman Guy Miege, who from 1668 taught languages in London says the following about the English practice:

The most famous case in the United Kingdom was that of

The most famous case in the United Kingdom was that of Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

St Margaret Clitherow, who, in order to avoid a trial in which her own children would be obliged to give evidence, was pressed to death on March 25, 1586, after refusing to plead to the charge of having harboured Catholic priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

s in her house. She died within fifteen minutes under a weight of at least . Several hardened criminals, including William Spigott (1721) and Edward Burnworth, lasted half an hour under before pleading to the indictment. Others, such as Major Strangways (1658) and John Weekes (1731), refused to plead, even under , and were killed when bystanders, out of mercy, sat on them.

The only death by ''peine forte et dure'' in American history was that of Giles Corey, who was pressed to death on September 19, 1692, during the Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Not everyone wh ...

, after he refused to enter a plea in the judicial proceeding. According to legend, his last words as he was being crushed were "More weight", and he was thought to be dead as the weight was applied.

In medieval Europe the slow crushing of body parts in screw-operated ‘bone vises’ of iron was a common method of torture, and a tremendous variety of cruel instruments was used to savagely crush the head, knee, hand, and, most commonly, either the thumb or the naked foot. Such instruments were finely threaded and variously provided with spiked inner surfaces or heated red-hot before their application to the limb to be tortured.

In popular culture

''Peine forte et dure'' is referred to in Arthur Miller's political drama ''The Crucible

''The Crucible'' is a 1953 play by the American playwright Arthur Miller. It is a dramatized and partially fictionalized story of the Salem witch trials that took place in the Province of Massachusetts Bay from 1692 to 1693. Miller wrote ...

'' (1953), where Giles Corey is pressed to death after refusing to plead "aye or nay" to the charge of witchcraft. In the 1996 film version of this play, the screenplay also written by Arthur Miller, Corey is crushed to death for refusing to reveal the name of a source of information.

In the 1970 American made-for-television supernatural horror film

Supernatural horror film is a film genre that combines aspects of supernatural film and horror film. Supernatural occurrences in such films often include ghosts and demons, and many supernatural horror films have elements of religion. Common them ...

'' Crowhaven Farm'', directed by Walter Grauman and starring Hope Lange, Paul Burke and John Carradine

John Carradine ( ; born Richmond Reed Carradine; February 5, 1906 – November 27, 1988) was an American actor, considered one of the greatest character actors in American cinema. He was a member of Cecil B. DeMille's stock company and later J ...

, a coven

A coven () is a group or gathering of Witchcraft, witches. The word "coven" (from Anglo-Norman language, Anglo-Norman ''covent, cuvent'', from Old French ''covent'', from Latin ''conventum'' = convention) remained largely unused in English lan ...

uses crushing to torture Lange's character after she inherits a haunted Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

farm house.

In '' The Dark Pictures Anthology: Little Hope'' one of the flashback victims Joseph Lambert is subjected to the peine forte et dure method of crushing, therefore becoming the ‘crushed demon’ that stalks his reincarnation, John, later in the game.

In the 2017 BBC One

BBC One is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It is the corporation's oldest and flagship channel, and is known for broadcasting mainstream programming, which includes BBC News television b ...

series ''Gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

'' the public execution by crushing of the fictional Lady Dorothy Dibdale (based on Margaret Clitherow

Margaret Clitherow (''née'' Middleton, ''c.'' 1556 – 25 March 1586) was an English Catholic recusant known as The Pearl of York. She was pressed to death for refusing to enter a plea to the charge of harbouring Catholic priests. She was can ...

) is shown in graphic detail.

See also

*Stoning

Stoning, or lapidation, is a method of capital punishment where a group throws stones at a person until the subject dies from blunt trauma. It has been attested as a form of punishment for grave misdeeds since ancient times.

Stoning appears t ...

* Cement shoes

* Crush syndrome

Crush syndrome (also traumatic rhabdomyolysis or Bywaters' syndrome) is a medical condition characterized by major shock and kidney failure after a crushing injury to skeletal muscle. It should not be confused with crush injury, which is the c ...

References

Further reading

*McKenzie, Andrea. "'This Death Some Strong and Stout Hearted Man Doth Choose': The Practice of Peine Forte et Dure in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century England". ''Law and History Review'', Summer 2005, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 279–31External links

Forfeiture in England and Colonial America

''The Proceedings of the Old Bailey,'' Reference Number: t16760823-6 (23 August 1676)

{{Capital punishment Execution methods Torture