Corporativist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Corporatism is an ideology and political system of interest representation and policymaking whereby

Corporatism is an ideology and political system of interest representation and policymaking whereby

Sociologist

Sociologist

A fascist corporation can be defined as a government-directed confederation of employers and employees unions, with the aim of overseeing production in a comprehensive manner. Theoretically, each corporation within this structure assumes the responsibility of advocating for the interests of its respective profession, particularly through the negotiation of labor agreements and similar measures. Fascists theorized that this method could result in harmony amongst social classes.

In Italy, from 1922 until 1943, corporatism became influential amongst Italian nationalists led by

A fascist corporation can be defined as a government-directed confederation of employers and employees unions, with the aim of overseeing production in a comprehensive manner. Theoretically, each corporation within this structure assumes the responsibility of advocating for the interests of its respective profession, particularly through the negotiation of labor agreements and similar measures. Fascists theorized that this method could result in harmony amongst social classes.

In Italy, from 1922 until 1943, corporatism became influential amongst Italian nationalists led by

Guilds and civil society in European political thought from the twelfth century to present

'. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, . * * * *

Economic Adjustment and Political Transformation in Small States

'. Oxford University Press. *Jones, R. J. Barry. ''Routledge Encyclopedia of International Political Economy: Entries A-F''. Taylor & Frances, 2001. . *Schmitter, P. (1974)

"Still the Century of Corporatism?"

''The Review of Politics'', 36(1), 85-131. * Taha Parla and Andrew Davison, ''Corporatist Ideology in Kemalist Turkey Progress or Order?'', 2004, Syracuse University Press,

''Rerum novarum'': encyclical of Pope Leo XIII on capital and labor

The 1928 autobiography of Benito Mussolini. Online.

'' My Autobiography''. Book by Benito Mussolini; Charles Scribner's Sons, 1928. . *

' 1965, 1971. Harvard University Press. . * Schmitter, P. C. and Lehmbruch, G. (eds.). ''Trends toward Corporatist Intermediation.'' London, 1979. . * Rodrigues, Lucia Lima.

Corporatism, liberalism and the accounting profession in Portugal since 1755

" ''Journal of Accounting Historians,'' June 2003. *

Corporatism

–

Corporatism

–

Professor Thayer Watkins, ''The economic system of corporatism''

,

Chip Berlet, "Mussolini on the Corporate State"

2005, Political Research Associates. {{Authority control Collectivism Economic ideologies Fascism Political systems Political theories

corporate groups

A corporate group, company group or business group, also formally known as a group of companies, is a collection of parent and subsidiary corporations that function as a single economic entity through a common source of control. These types of gr ...

, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, come together and negotiate contracts or policy (collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and labour rights, rights for ...

) on the basis of their common interests. The term is derived from the Latin ''corpus'', or "body".

Corporatism does not refer to a political system dominated by large business interests, even though the latter are commonly referred to as "corporations" in modern American vernacular and legal parlance. Instead, the correct term for that theoretical system would be corporatocracy

Corporatocracy or corpocracy is an economic, political and judicial system controlled or influenced by business corporations or corporate Interest group, interests.

The concept has been used in explanations of bank bailouts, excessive pay for ...

. The terms "corporatocracy" and "corporatism" are often confused due to their similar names and to the use of corporations as organs of the state.

Corporatism developed during the 1850s in response to the rise of classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited governmen ...

and Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

, and advocated cooperation between the classes instead of class conflict

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

. Adherents of diverse ideologies, including economic liberalism

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberalism ...

, fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

, and social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

have advocated for corporatist models. Corporatism became one of the main tenets of Italian fascism

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

, and Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

's Fascist regime in Italy advocated the total integration of divergent interests into the state for the common good. However, the more democratic neo-corporatism often embraced tripartism

Tripartism is an economic system of neo-corporatism based on a mixed economy and tripartite contracts between employers' organizations, trade unions, and the government of a country. Each is to act as a social partner to create economic policy ...

.

Corporatist ideas have been expressed since ancient Greek and Roman societies, and have been integrated into Catholic social teaching

Catholic social teaching (CST) is an area of Catholic doctrine which is concerned with human dignity and the common good in society. It addresses oppression, the role of the state, subsidiarity, social organization, social justice, and w ...

and Christian democratic

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well ...

political parties. They have been paired by various advocates and implemented in various societies with a wide variety of political systems, including authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

, absolutism, fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

, liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

, and social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

.

Kinship corporatism

Kinship

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says that ...

-based corporatism emphasizing clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

, ethnic and family identification has been a common phenomenon in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, and Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

. Confucian societies based upon families and clans in Eastern and Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

have been considered types of corporatism. Islamic societies often feature strong clans which form the basis for a community-based corporatist society. Family business

A family business is a commercial organization in which decision-making is influenced by multiple generations of a family, related by Consanguinity , blood, marriage or adoption, who has both the ability to influence the vision of the business a ...

es are common worldwide in capitalist societies.

Politics and political economy

Communitarian corporatism

Early concepts of corporatism evolved inClassical Greece

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BC) in ancient Greece,The "Classical Age" is "the modern designation of the period from about 500 B.C. to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C." ( Thomas R. Mar ...

. Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

developed the concept of a totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

and communitarian

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based on the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relation ...

corporatist system of natural-based classes and natural social hierarchies that would be organized based on function, such that groups would cooperate to achieve social harmony by emphasizing collective

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or interest or work together to achieve a common objective. Collectives can differ from cooperatives in that they are not necessarily focused upon an e ...

interests while rejecting individual interests.

In ''Politics'', Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

described society as being divided between natural classes and functional purposes: those of priests, rulers, slaves and warriors. Ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

adopted Greek concepts of corporatism into its own version of corporatism, adding the concept of political representation on the basis of function that divided representatives into military, professional and religious groups and set up institutions for each group known as ''collegia''.

After the 5th-century fall of Rome and the beginning of the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

, corporatist organizations in western Europe became largely limited to religious order

A religious order is a subgroup within a larger confessional community with a distinctive high-religiosity lifestyle and clear membership. Religious orders often trace their lineage from revered teachers, venerate their Organizational founder, ...

s and to the idea of Christian brotherhood—especially within the context of economic transactions. From the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

onward, corporatist organizations became increasingly common in Europe, including such groups as religious orders, monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone ( hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which m ...

, fraternities

A fraternity (; whence, " brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club or fraternal order traditionally of men but also women associated together for various religious or secular aims. Fraternity in the Western conce ...

, military orders such as the Knights Templar

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, mainly known as the Knights Templar, was a Military order (religious society), military order of the Catholic Church, Catholic faith, and one of the most important military ord ...

and the Teutonic Order

The Teutonic Order is a religious order (Catholic), Catholic religious institution founded as a military order (religious society), military society in Acre, Israel, Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Sa ...

, educational organizations such as the emerging European universities and learned societies

A learned society ( ; also scholarly, intellectual, or academic society) is an organization that exists to promote an academic discipline, profession, or a group of related disciplines such as the arts and sciences. Membership may be open to al ...

, the chartered towns

A town is a type of a human settlement, generally larger than a village but smaller than a city.

The criteria for distinguishing a town vary globally, often depending on factors such as population size, economic character, administrative stat ...

and cities

A city is a human settlement of a substantial size. The term "city" has different meanings around the world and in some places the settlement can be very small. Even where the term is limited to larger settlements, there is no universally agree ...

, and most notably the guild system which dominated the economies of population centers in Europe. The military orders notably gained prominence during the period of the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

. These corporatist systems co-existed with the governing medieval estates system, and members of the first estate (the clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

), the second estate (the aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

), and third estate (the common people

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neithe ...

) could also participate in various corporatist bodies. The development of the guild system involved the guilds gaining the power to regulate trade and prices, and guild members included artisans, tradesmen, and other professionals

A professional is a member of a profession or any person who works in a specified professional activity. The term also describes the standards of education and training that prepare members of the profession with the particular knowledge and ski ...

. This diffusion of power is an important aspect of corporatist economic models of economic management and class collaboration

Class collaboration is a principle of social organization based upon the belief that the division of society into a hierarchy of social classes is a positive and essential aspect of civilization.

Fascist support

Class collaboration is one of ...

. However, from the 16th century onward, absolute monarchies began to conflict with the diffuse, decentralized powers of the medieval corporatist bodies. Absolute monarchies during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

and Enlightenment gradually subordinated corporatist systems and corporate groups to the authority of centralized and absolutist governments, removing any checks on royal power these corporatist bodies had previously utilized.

After the outbreak of the French Revolution (1789), the existing absolutist corporatist system in France was abolished due to its endorsement of social hierarchy and special "corporate privilege". The new French government considered corporatism's emphasis on group rights as inconsistent with the government's promotion of individual rights. Subsequently, corporatist systems and corporate privilege throughout Europe were abolished in response to the French Revolution. From 1789 to the 1850s, most supporters of corporatism were reactionaries

In politics, a reactionary is a person who favors a return to a previous state of society which they believe possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary.''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'' Third Edition, (1999) p. 729. ...

. A number of reactionary corporatists favoured corporatism in order to end liberal capitalism and to restore the feudal system

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structuring socie ...

. Countering the reactionaries were the ideas of Henri de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon (; ; 17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), better known as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on po ...

(1760- 1825), whose proposed "industrial class" would have had the representatives of various economic groups sit in the political chambers, in contrast to the popular representation of liberal democracy.

Social corporatism

From the 1850s onward, progressive corporatism developed in response toclassical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited governmen ...

and to Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

. Progressive corporatists supported providing group rights to members of the middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

es and working classes

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

in order to secure co-operation among the classes. This was in opposition to the Marxist conception of class conflict

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

. By the 1870s and 1880s, corporatism experienced a revival in Europe with the formation of workers' unions that were committed to negotiations with employers.

In his 1887 work ''Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft'' ("Community and Society"), Ferdinand Tönnies

Ferdinand Tönnies (; 26 July 1855 – 8 April 1936) was a German sociologist, economist, and philosopher. He was a significant contributor to sociological theory and field studies, best known for distinguishing between two types of social gro ...

began a major revival of corporatist philosophy associated with the development of neo-medievalism

Neo-medievalism (or neomedievalism, new medievalism) is a term with a long history that has acquired specific technical senses in two branches of scholarship. In political theory about modern international relations, where the term is originally a ...

, increasing promotion of guild socialism

Guild socialism is an ideology and a political movement advocating workers' control of industry through the medium of trade-related guilds "in an implied contractual relationship with the public". It originated in the United Kingdom and was at ...

and causing major changes to theoretical sociology. Tönnies claims that organic communities based upon clans, communes, families and professional groups are disrupted by the mechanical society of economic classes imposed by capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

.Peter F. Klarén, Thomas J. Bossert. ''Promise of development: theories of change in Latin America''. Boulder, Colorado, USA: Westview Press, 1986. P. 221. The German Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

used Tönnies' theory to promote their notion of ''Volksgemeinschaft

''Volksgemeinschaft'' () is a German expression meaning "people's community", "folk community", Richard Grunberger, ''A Social History of the Third Reich'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971, p. 44. "national community", or "racial community" ...

'' ("people's community"). However, Tönnies opposed Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

: he joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany ( , SPD ) is a social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany. Saskia Esken has been the party's leader since the 2019 leadership election together w ...

in 1932 to oppose fascism in Germany and was deprived of his honorary professorship by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

in 1933.

Corporatism in the Roman Catholic Church

In 1881,Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (; born Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2March 181020July 1903) was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 until his death in July 1903. He had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of Peter the Ap ...

commissioned theologians and social thinkers to study corporatism and to provide a definition for it. In 1884 in Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau or simply Freiburg is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fourth-largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, Mannheim and Karlsruhe. Its built-up area has a population of abou ...

, the commission declared that corporatism was a "system of social organization that has at its base the grouping of men according to the community of their natural interests and social functions, and as true and proper organs of the state they direct and coordinate labor and capital in matters of common interest". Corporatism is related to the sociological

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociology was coined in ...

concept of structural functionalism

Structural functionalism, or simply functionalism, is "a framework for building theory that sees society as a complex system whose parts work together to promote solidarity and stability".

This approach looks at society through a macro-level o ...

.

Corporatism's popularity increased in the late 19th century and a corporatist internationale was formed in 1890, followed by the 1891 publishing of ''Rerum novarum

''Rerum novarum'', or ''Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor'', is an encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII on 15 May 1891. It is an open letter, passed to all Catholic patriarchs, primates, archbishops, and bishops, which addressed the condi ...

'' by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

that for the first time declared the Church's blessing to trade unions and recommended that politicians recognize organized labour. Many corporatist unions in Europe were endorsed by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

to challenge the anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

, Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

and other radical unions, with the corporatist unions being fairly conservative in comparison to their radical rivals. Some Catholic corporatist states include Austria under the 1932–1934 leadership

Leadership, is defined as the ability of an individual, group, or organization to "", influence, or guide other individuals, teams, or organizations.

"Leadership" is a contested term. Specialist literature debates various viewpoints on the co ...

of Federal Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss

Engelbert Dollfuss (alternatively Dollfuß; 4 October 1892 – 25 July 1934) was an Austrian politician and dictator who served as chancellor of Federal State of Austria, Austria between 1932 and 1934. Having served as Minister for Forests and ...

and Ecuador under the leadership of García Moreno (1861–1865 and 1869–1875). The economic vision outlined in ''Rerum novarum

''Rerum novarum'', or ''Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor'', is an encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII on 15 May 1891. It is an open letter, passed to all Catholic patriarchs, primates, archbishops, and bishops, which addressed the condi ...

'' and ''Quadragesimo anno

''Quadragesimo anno'' () (Latin for "In the 40th Year") is an encyclical issued by Pope Pius XI on 15 May 1931, 40 years after Leo XIII's encyclical '' Rerum novarum'', further developing Catholic social teaching. Unlike Leo XIII, who addre ...

'' (1931) also influenced the régime (1946–1955 and 1973–1974) of Juan Perón

Juan Domingo Perón (, , ; 8 October 1895 – 1 July 1974) was an Argentine military officer and Statesman (politician), statesman who served as the History of Argentina (1946-1955), 29th president of Argentina from 1946 to Revolución Libertad ...

and Justicialism

Peronism, also known as justicialism, is an Argentine ideology and movement based on the ideas, doctrine and legacy of Juan Perón (1895–1974). It has been an influential movement in 20th- and 21st-century Argentine politics. Since 1946, Pe ...

in Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

and influenced the drafting of the 1937 Constitution of Ireland

The Constitution of Ireland (, ) is the constitution, fundamental law of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It asserts the national sovereignty of the Irish people. It guarantees certain fundamental rights, along with a popularly elected non-executi ...

. In response to the Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

corporatism of the 1890s, Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

corporatism developed, especially in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

and Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

. However, Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

corporatism has been much less successful in obtaining assistance from governments than its Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

counterpart.

Corporate solidarism

Sociologist

Sociologist Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim (; or ; 15 April 1858 – 15 November 1917) was a French Sociology, sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern soci ...

(1858-1917) advocated a form of corporatism termed "solidarism" that advocated creating an organic social solidarity

Solidarity or solidarism is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. True solidarity means moving beyond individual identities and single issue politics ...

of society through functional representation.Antony Black, pp. 226. Solidarism built on Durkheim's view that the dynamic of human society as a collective

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or interest or work together to achieve a common objective. Collectives can differ from cooperatives in that they are not necessarily focused upon an e ...

is distinct from the dynamic of an individual, in that society is what places upon individuals their cultural and social attributes.

Durkheim posited that solidarism would alter the division of labour

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise ( specialisation). Individuals, organisations, and nations are endowed with or acquire specialised capabilities, a ...

by evolving it from mechanical solidarity

Solidarity or solidarism is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. True solidarity means moving beyond individual identities and single issue politics ...

to organic solidarity. He believed that the existing industrial capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

division of labour caused "juridical and moral ''anomie

In sociology, anomie or anomy () is a social condition defined by an uprooting or breakdown of any moral values, standards or guidance for individuals to follow. Anomie is believed to possibly evolve from conflict of belief systems and causes b ...

''", which had no norms or agreed procedures to resolve conflicts and resulted in chronic confrontation between employers and trade unions. Durkheim believed that this anomie caused social dislocation and felt that by this "it is the law of the strongest which rules, and there is inevitably a chronic state of war, latent or acute". As a result, Durkheim believed it is a moral obligation of the members of society to end this situation by creating a moral organic solidarity based upon profession

A profession is a field of Work (human activity), work that has been successfully professionalized. It can be defined as a disciplined group of individuals, professionals, who adhere to ethical standards and who hold themselves out as, and are ...

s as organized into a single public institution.

Corporate solidarism is a form of corporatism that advocates creating solidarity

Solidarity or solidarism is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. True solidarity means moving beyond individual identities and single issue politics ...

instead of collectivism

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and groups. Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership, struct ...

in society through functional representation, believing that it is up to the people to end the chronic confrontation between employers and labor unions by creating a single public institution. Solidarism rejects a "materialistic" approach to social, economic, and political problems, while also rejecting class conflict

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

. Just like corporatism, it embraces tripartism

Tripartism is an economic system of neo-corporatism based on a mixed economy and tripartite contracts between employers' organizations, trade unions, and the government of a country. Each is to act as a social partner to create economic policy ...

as its economic system.

Liberal corporatism

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

discussed corporatist-like economic associations as needing to "predominate" in society to create equality for labourers and to give them influence with management by economic democracy

Economic democracy (sometimes called a democratic economy) is a socioeconomic philosophy that proposes to shift ownership and decision-making power from corporate shareholders and corporate managers (such as a board of directors) to a larger ...

. Unlike some other types of corporatism, liberal corporatism does not reject capitalism or individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

, but believes that capitalist companies are social institutions that should require their managers to do more than maximize net income

In business and Accountancy, accounting, net income (also total comprehensive income, net earnings, net profit, bottom line, sales profit, or credit sales) is an entity's income minus cost of goods sold, expenses, depreciation and Amortization (a ...

by recognizing the needs of their employees.Waring, Stephen P. ''Taylorism Transformed: Scientific Management Theory Since 1945''. University of North Carolina Press, 1994. Pp. 193.

This liberal corporatist ethic is similar to Taylorism

Scientific management is a theory of management that analyzes and synthesizes workflows. Its main objective is improving economic efficiency, especially labor productivity. It was one of the earliest attempts to apply science to the engineer ...

but endorses democratization of capitalist companies. Liberal corporatists believe that inclusion of all members in the election of management in effect reconciles "ethics and efficiency, freedom and order, liberty and rationality".

Liberal corporatism began to gain disciples in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

during the late 19th century. Economic liberal corporatism involving capital-labour cooperation was influential in Fordism

Fordism is an industrial engineering and manufacturing system that serves as the basis of modern social and labor-economic systems that support industrialized, standardized mass production and mass consumption. The concept is named after Henry ...

. Liberal corporatism has also been an influential component of the liberalism in the United States

Liberalism in the United States is based on concepts of unalienable rights of the individual. The fundamental liberal ideals of consent of the governed, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, the separation of church and st ...

that has been referred to as "interest group liberalism".

Fascist corporatism

A fascist corporation can be defined as a government-directed confederation of employers and employees unions, with the aim of overseeing production in a comprehensive manner. Theoretically, each corporation within this structure assumes the responsibility of advocating for the interests of its respective profession, particularly through the negotiation of labor agreements and similar measures. Fascists theorized that this method could result in harmony amongst social classes.

In Italy, from 1922 until 1943, corporatism became influential amongst Italian nationalists led by

A fascist corporation can be defined as a government-directed confederation of employers and employees unions, with the aim of overseeing production in a comprehensive manner. Theoretically, each corporation within this structure assumes the responsibility of advocating for the interests of its respective profession, particularly through the negotiation of labor agreements and similar measures. Fascists theorized that this method could result in harmony amongst social classes.

In Italy, from 1922 until 1943, corporatism became influential amongst Italian nationalists led by Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

. The 1920 Charter of Carnaro gained much popularity as the prototype of a "corporative state", having displayed much within its tenets as a guild system combining the concepts of autonomy and authority in a special synthesis. Alfredo Rocco

Alfredo Rocco (9 September 1875 – 28 August 1935) was an Italian politician and jurist. He was Professor of Commercial Law at the University of Urbino (1899–1902) and in Macerata (1902–1905), then Professor of Civil Procedure in Parma, of ...

spoke of a corporative state and declared corporatist ideology in detail. Rocco would later become a member of the Italian fascist régime.

Subsequently, the Labour Charter of 1927 was implemented, thus establishing a collective agreement

A collective agreement, collective labour agreement (CLA) or collective bargaining agreement (CBA) is a written contract negotiated through collective bargaining for employees by one or more trade unions with the management of a company (or with a ...

system between employers and employees, becoming the main form of class collaboration

Class collaboration is a principle of social organization based upon the belief that the division of society into a hierarchy of social classes is a positive and essential aspect of civilization.

Fascist support

Class collaboration is one of ...

in the fascist government.

Italian Fascism

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

involved a corporatist political system in which the economy was collectively managed by employers, workers and state officials by formal mechanisms at the national level. Its supporters claimed that corporatism could better recognize or "incorporate" every divergent interest into the state organically, unlike majority-rules democracy, which (they said) could marginalize specific interests. This total consideration was the inspiration for their use of the term "totalitarian", described without coercion (which is connoted in the modern meaning) in the 1932 ''Doctrine of Fascism

"The Doctrine of Fascism" () is an essay attributed to Benito Mussolini. In truth, the first part of the essay, entitled , was written by the Italian philosopher Giovanni Gentile, while only the second part is the work of Mussolini himself.

O ...

'' as thus:

A popular slogan of the Italian Fascists under Mussolini was "" ("everything within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state").

Within the corporative model of Italian fascism each corporate interest was supposed to be resolved and incorporated under the state. Much of the corporatist influence upon Italian fascism was partly due to the Fascists' attempts to gain endorsement by the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

that itself sponsored corporatism. However, the Roman Catholic Church's corporatism favored a bottom-up corporatism, whereby groups such as families and professional groups would voluntarily work together, whereas fascist corporatism was a top-down model of state control managed primarily by government officials.

The fascist state corporatism of Roman Catholic Italy influenced the governments and economies — not only of other Roman Catholic-majority countries, such as the governments of Engelbert Dollfuss

Engelbert Dollfuss (alternatively Dollfuß; 4 October 1892 – 25 July 1934) was an Austrian politician and dictator who served as chancellor of Federal State of Austria, Austria between 1932 and 1934. Having served as Minister for Forests and ...

in Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, António de Oliveira Salazar

António de Oliveira Salazar (28 April 1889 – 27 July 1970) was a Portuguese statesman, academic, and economist who served as Portugal's President of the Council of Ministers of Portugal, President of the Council of Ministers from 1932 to 1 ...

in Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, Juan Domingo Perón

''Juan'' is a given name, the Spanish and Manx versions of '' John''. The name is of Hebrew origin and has the meaning "God has been gracious." It is very common in Spain and in other Spanish-speaking countries around the world and in the Philip ...

in Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

and Getúlio Vargas

Getúlio Dornelles Vargas (; ; 19 April 1882 – 24 August 1954) was a Brazilian lawyer and politician who served as the 14th and 17th president of Brazil, from 1930 to 1945 and from 1951 until his suicide in 1954. Due to his long and contr ...

in Brazil — but also of Konstantin Päts

Konstantin Päts ( – 18 January 1956) was an Estonian statesman and the country's president from 1938 to 1940. Päts was one of the most influential politicians of the independent democratic Republic of Estonia, and during the two decades p ...

and Kārlis Ulmanis

Kārlis Augusts Vilhelms Ulmanis (; 4 September 1877 – 20 September 1942) was a Latvian politician and a dictator. He was one of the most prominent Latvian politicians of pre-World War II Latvia during the Interwar period of independence from N ...

in non-Catholic Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

and Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

.

Fascists in non-Catholic countries also supported Italian Fascist corporatism, including Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980), was a British aristocrat and politician who rose to fame during the 1920s and 1930s when he, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, turned to fascism. ...

of the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

, who commended corporatism and said that "it means a nation organized as the human body, with each organ performing its individual function but working in harmony with the whole". Mosley also regarded corporatism as an attack on ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

'' economics and "international finance".

The corporatist state of Portugal had similarities to Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

's Italian fascist corporatism, but also differences in its moral approach to governing. Although Salazar admired Mussolini and was influenced by his Labour Charter of 1927, he distanced himself from fascist dictatorship, which he considered a pagan Caesarist political system that recognised neither legal nor moral limits. Salazar also had a strong dislike of Marxism and liberalism.

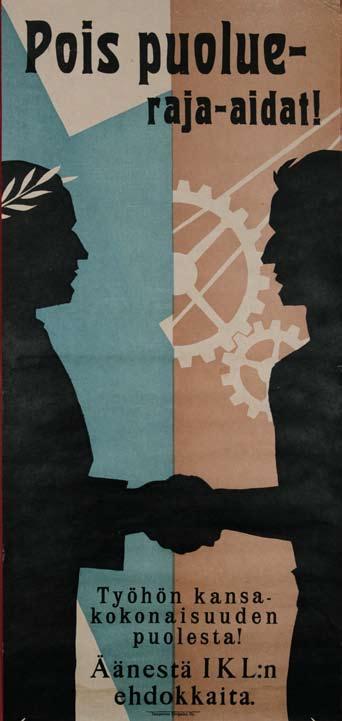

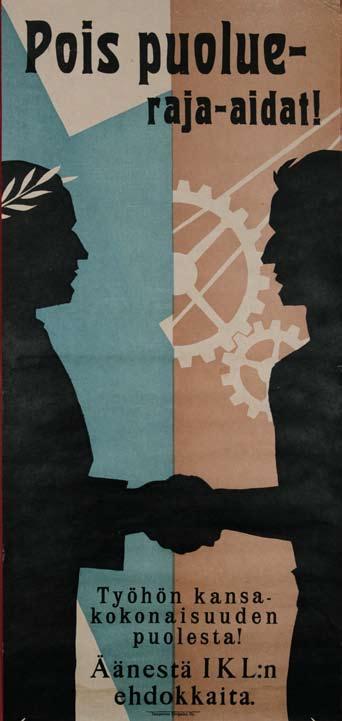

In 1933, Salazar stated: Our Dictatorship clearly resembles a fascist dictatorship in the reinforcement of authority, in the war declared against certain principles of democracy, in its accentuated nationalist character, in its preoccupation of social order. However, it differs from it in its process of renovation. The fascist dictatorship tends towards a pagan Caesarism, towards a state that knows no limits of a legal or moral order, which marches towards its goal without meeting complications or obstacles. The Portuguese New State, on the contrary, cannot avoid, not think of avoiding, certain limits of a moral order which it may consider indispensable to maintain in its favour of its reforming action.The Patriotic People's Movement (IKL) in Finland envisioned a system with elements of direct democracy and professional parliament. The president would be elected with direct vote, who would then appoint the government from among professionals in their respective fields. All parties would be banned, and members of parliament would be elected by vote from corporate groups representing different sectors; Agriculture, Industry and Public servants, free trades, etc. Every law passed in the parliament would be either ratified or overturned by a referendum.

Neo-corporatism

During the post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

reconstruction period in Europe, corporatism was favored by Christian democrats (often under the influence of Catholic social teaching

Catholic social teaching (CST) is an area of Catholic doctrine which is concerned with human dignity and the common good in society. It addresses oppression, the role of the state, subsidiarity, social organization, social justice, and w ...

), national conservatives and social democrats

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

in opposition to liberal capitalism. This type of corporatism became unfashionable but revived again in the 1960s and 1970s as "neo-corporatism" in response to the new economic threat of recession-inflation.

Neo-corporatism is a democratic form of corporatism which favors economic tripartism

Tripartism is an economic system of neo-corporatism based on a mixed economy and tripartite contracts between employers' organizations, trade unions, and the government of a country. Each is to act as a social partner to create economic policy ...

, which involves strong labour union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

s, employers' associations and governments that cooperate as "social partners

{{cleanup rewrite, article, date=June 2014

Social partners are groups that cooperate in working relationships to achieve a mutually agreed-upon goal, typically for the benefit of all involved groups. Examples of social partners include employers, e ...

" to negotiate and manage a national economy. Social corporatist systems instituted in Europe after World War II include the ordoliberal system of the social market economy

The social market economy (SOME; ), also called Rhine capitalism, Rhine-Alpine capitalism, the Rhenish model, and social capitalism, is a socioeconomic model combining a free-market capitalist economic system with social policies and enough re ...

in Germany, the social partnership in Ireland, the polder model

The polder model () is a method of consensus decision-making, based on the Dutch version of consensus-based economic and social policymaking in the 1980s and 1990s.Ewoud Sanders, ''Woorden met een verhaal'' (Amsterdam / Rotterdam, 2004), 104–06 ...

in the Netherlands (although arguably the polder model already was present at the end of World War I, it was not until after World War II that a social-service system gained foothold there), the concertation system in Italy, the Rhine model in Switzerland and the Benelux countries and the Nordic model

The Nordic model comprises the economic and social policies as well as typical cultural practices common in the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden). This includes a comprehensive welfare state and multi-level colle ...

in the Nordic countries.

Attempts in the United States to create neo-corporatist capital-labor arrangements were unsuccessfully advocated by Gary Hart

Gary Warren Hart (''né'' Hartpence; born November 28, 1936) is an American politician, diplomat, and lawyer. He was the front-runner for the 1984 and 1988 Democratic presidential nominations, until in 1988, he dropped out amid revelations of ex ...

and Michael Dukakis

Michael Stanley Dukakis ( ; born November 3, 1933) is an American politician and lawyer who served as governor of Massachusetts from 1975 to 1979 and from 1983 to 1991. He is the longest-serving governor in Massachusetts history and only the s ...

in the 1980s. As secretary of labor during the Clinton administration, Robert Reich

Robert Bernard Reich (; born June 24, 1946) is an American professor, author, lawyer, and political commentator. He worked in the administrations of presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, and he served as United States Secretary of Labor, Se ...

promoted neo-corporatist reforms.Waring, Stephen P. ''Taylorism Transformed: Scientific Management Theory Since 1945''. University of North Carolina Press, 1994. Pp. 194.

Contemporary examples by country

China

Jonathan Unger and Anita Chan in their essay "China, Corporatism, and the East Asian Model" describe Chinese corporatism as follows:the national level the state recognizes one and only one organization (say, a national labour union, a business association, a farmers' association) as the sole representative of the sectoral interests of the individuals, enterprises or institutions that comprise that organization's assigned constituency. The state determines which organizations will be recognized as legitimate and forms an unequal partnership of sorts with such organizations. The associations sometimes even get channelled into the policy-making processes and often help implement state policy on the government's behalf.By establishing itself as the arbiter of legitimacy and assigning responsibility for a particular

constituency

An electoral (congressional, legislative, etc.) district, sometimes called a constituency, riding, or ward, is a geographical portion of a political unit, such as a country, state or province, city, or administrative region, created to provi ...

with one sole organization, the state limits the number of players with which it must negotiate its policies and co-opts their leadership into policing their own members. This arrangement is not limited to economic organizations such as business groups and social organizations.

The political scientist Jean C. Oi

Jean C. Oi (Chinese name: zh, c=戴慕珍, hp=Dài Mùzhēn) is an American political scientist and expert in the politics of China. She is the William Haas Professor in Chinese Politics in the department of political science at Stanford Univers ...

coined the term "local state corporatism" to describe China's distinctive type of state-led growth, in which a communist party-state with Leninist

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

roots commits itself to policies which are friendly to the market and to growth.

The use of corporatism as a framework to understand the central state's behaviour in China has been criticized by authors such as Bruce Gilley and William Hurst.

Hong Kong and Macau

In two special administrative regions, some legislators are chosen by functional constituencies (Legislative Council of Hong Kong

The Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, colloquially known as LegCo, is the Unicameralism, unicameral legislature of Hong Kong. It sits under People's Republic of China, China's "one country, two systems" c ...

) where the voters are a mix of individuals, associations, and corporations or indirect election

An indirect election or ''hierarchical voting,'' is an election in which voters do not choose directly among candidates or parties for an office ( direct voting system), but elect people who in turn choose candidates or parties. It is one of the o ...

(Legislative Assembly of Macau

The Legislative Assembly of the Macau Special Administrative Region is the organ of the legislative branch of Macau. It is a 33-member body comprising 14 directly elected members, 12 indirectly elected members representing Functional constitu ...

) where a single association is designated to appoint legislators.

Ireland

Most members of theSeanad Éireann

Seanad Éireann ( ; ; "Senate of Ireland") is the senate of the Oireachtas (the Irish legislature), which also comprises the President of Ireland and Dáil Éireann (defined as the house of representatives).

It is commonly called the Seanad or ...

, the upper house of the Oireachtas

The Oireachtas ( ; ), sometimes referred to as Oireachtas Éireann, is the Bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The Oireachtas consists of the president of Ireland and the two houses of the Oireachtas (): a house ...

(parliament) of Ireland, are elected as part of vocational panel

A vocational panel () is any of five lists of candidates from which are elected a total of 43 of the 60 senators in Seanad Éireann, the upper house of the Oireachtas (parliament) of Ireland. Each panel corresponds to a grouping of "interests and ...

s nominated partly by current Oireachtas members and partly by vocational and special interest associations. The Seanad also includes two university constituencies

A university constituency is a constituency, used in elections to a legislature, that represents the members of one or more universities rather than residents of a geographical area. These may or may not involve plural voting, in which voters ar ...

.

The Constitution of Ireland

The Constitution of Ireland (, ) is the constitution, fundamental law of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It asserts the national sovereignty of the Irish people. It guarantees certain fundamental rights, along with a popularly elected non-executi ...

of 1937 was influenced by Roman Catholic Corporatism as expressed in the papal encyclical, ''Quadragesimo anno'' (1931).

Netherlands

Under the Dutchpolder model

The polder model () is a method of consensus decision-making, based on the Dutch version of consensus-based economic and social policymaking in the 1980s and 1990s.Ewoud Sanders, ''Woorden met een verhaal'' (Amsterdam / Rotterdam, 2004), 104–06 ...

, the Social and Economic Council

The Social and Economic Council (Dutch language, Dutch: ''Sociaal-Economische Raad'', SER) is a major economic advisory council to the cabinet of the Netherlands. Formally it heads a Publiekrechtelijke Bedrijfsorganisatie, system of sector-based ...

of the Netherlands (Sociaal-Economische Raad, SER) was established by the 1950 Industrial Organisation Act (Wet op de bedrijfsorganisatie). It is led by representatives of unions, employer organizations, and government appointed experts. It advises the government and has administrative and regulatory power. It oversees Sectoral Organisation Under Public Law (Publiekrechtelijke Bedrijfsorganisatie

{{unreferenced, date=October 2018Publiekrechtelijke Bedrijfsorganisatie (in English ''Sectoral organisation under public law'', abbreviated PBO) is a Dutch form of government. PBOs are self-regulatory organizations for specific economic sectors.

...

, PBO) which are similarly organized by union and industry representatives, but for specific industries or commodities.

Slovenia

The Slovene National Council, the upper house of the Slovene Parliament, has 18 members elected on a corporatist basis.Western Europe

Generally supported bynationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

and/or social-democratic

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, socia ...

political parties, social corporatism developed in the post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

period, influenced by Christian democrats and social democrats in Western European countries such as Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Social corporatism has also been adopted in different configurations and to varying degrees in various Western European countries.

The Nordic countries have the most comprehensive form of collective bargaining, where trade unions

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

are represented at the national level by official organizations alongside employers' associations. Together with the welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

policies of these countries, this forms what is termed the Nordic model. Less extensive models exist in Austria and Germany which are components of Rhine capitalism.

See also

*Class collaboration

Class collaboration is a principle of social organization based upon the belief that the division of society into a hierarchy of social classes is a positive and essential aspect of civilization.

Fascist support

Class collaboration is one of ...

* Co-determination

* Conflict theories

Conflict theories are perspectives in political philosophy and sociology which argue that individuals and groups (social classes) within society interact on the basis of conflict rather than agreement, while also emphasizing social psychology ...

* Corporate statism

Corporate statism or state corporatism, referred to as corporativism by the Italian fascism, fascists, is a political culture and a form of corporatism the proponents of which claim or believe that corporate group (sociology), corporate groups sho ...

* Cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomy, autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned a ...

* Distributism

Distributism is an economic theory asserting that the world's productive assets should be widely owned rather than concentrated. Developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, distributism was based upon Catholic social teaching princi ...

* Fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

* Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

* Gremialismo

Gremialismo, or guildism, is a social, political, and economic ideology, inspired in the Catholic social teachings that claims that every correct social order should base itself in intermediary societies between persons and the state, which are ...

* Guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

* Guild socialism

Guild socialism is an ideology and a political movement advocating workers' control of industry through the medium of trade-related guilds "in an implied contractual relationship with the public". It originated in the United Kingdom and was at ...

* Holacracy

Holacracy is a method of decentralized management and organizational governance, which claims to distribute authority and decision-making through a holarchy of self-organizing teams rather than being vested in a management hierarchy. Holacracy ha ...

* Managerialism

Managerialism is the idea that professional managers should run organizations in line with organizational routines which produce controllable and measurable results. It applies the procedures of running a for-profit business to any organizatio ...

* Mutualism (movement)

Mutualism, also known as the movement of mutuals and the mutualist movement, is a social movement that aims at creating and promoting mutual organizations, mutual insurances and mutual funds. According to the prominent mutualist Gene Costa, the ...

* Integralism

* National syndicalism

National syndicalism is a socially far-right adaptation of syndicalism within the broader agenda of integral nationalism. National syndicalism developed in France in the early 20th century, and then spread to Italy, Spain, and Portugal.

F ...

* Paritarian Institutions

In the field of social protection, paritarian institutions are non-profit institutions which are jointly managed by the social partners (representatives of the employers and employees). In other words, the governance of these institutions is based ...

* Pillarisation

Pillarisation (a calque from the ) is the vertical separation of society into groups by religion and associated political beliefs. These societies were (and in some areas, still are) divided into two or more groups known as pillars (). The best-k ...

* Solidarism (disambiguation)

Solidarism or solidarist can refer to:

* The term "Corporatism#Corporate solidarism, solidarism" is applied to the sociopolitical thought advanced by Léon Bourgeois based on ideas by the sociologist Émile Durkheim which is loosely applied to a le ...

* Third Position

The Third Position is a set of neo-fascist political ideologies that were first described in Western Europe following the Second World War. Developed in the context of the Cold War, it developed its name through the claim that it represented ...

* Proprietary corporation

Notes

References

* Black, Antony (1984).Guilds and civil society in European political thought from the twelfth century to present

'. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, . * * * *

Further reading

* Acocella, N. and Di Bartolomeo, G.007

The ''James Bond'' franchise focuses on James Bond (literary character), the titular character, a fictional Secret Intelligence Service, British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels ...

"Is corporatism feasible?", in: ''Metroeconomica'', 58(2): 340-59.

* Jones, Eric. 2008. Economic Adjustment and Political Transformation in Small States

'. Oxford University Press. *Jones, R. J. Barry. ''Routledge Encyclopedia of International Political Economy: Entries A-F''. Taylor & Frances, 2001. . *Schmitter, P. (1974)

"Still the Century of Corporatism?"

''The Review of Politics'', 36(1), 85-131. * Taha Parla and Andrew Davison, ''Corporatist Ideology in Kemalist Turkey Progress or Order?'', 2004, Syracuse University Press,

On Italian corporatism

* Constitution of Fiume''Rerum novarum'': encyclical of Pope Leo XIII on capital and labor

On fascist corporatism and its ramifications

* Baker, David, "The political economy of fascism: Myth or reality, or myth and reality?", ''New Political Economy'', Volume 11, Issue 2 June 2006, pages 227–250. * Marra, Realino, "''Aspetti dell'esperienza corporativa nel periodo fascista'', ''Annali della Facoltà di Giurisprudenza di Genova'', XXIV-1.2, 1991–92, pages 366–79. * There is an essay on "The Doctrine of Fascism" credited toBenito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

that appeared in the 1932 edition of the ''Enciclopedia Italiana'', and excerpts can be read at Doctrine of Fascism

"The Doctrine of Fascism" () is an essay attributed to Benito Mussolini. In truth, the first part of the essay, entitled , was written by the Italian philosopher Giovanni Gentile, while only the second part is the work of Mussolini himself.

O ...

. There are also links there to the complete text.

* ''My rise and fall'', Volumes 1–2 – two autobiographies of Mussolini, editors Richard Washburn Child, Max Ascoli

Max Ascoli (June 25, 1898 – January 1, 1978) was a Jewish Italian-American professor of political philosophy and law at the New School for Social Research, United States of America.

Career

Ascoli's career started in Italy and continued in th ...

, Richard Lamb, Da Capo Press, 1998

The 1928 autobiography of Benito Mussolini. Online.

'' My Autobiography''. Book by Benito Mussolini; Charles Scribner's Sons, 1928. . *

On neo-corporatism

* Katzenstein, Peter. ''Small States in World Markets: industrial policy in Europe.'' Ithaca, 1985. Cornell University Press. . * Olson, Mancur. '' The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups' 1965, 1971. Harvard University Press. . * Schmitter, P. C. and Lehmbruch, G. (eds.). ''Trends toward Corporatist Intermediation.'' London, 1979. . * Rodrigues, Lucia Lima.

Corporatism, liberalism and the accounting profession in Portugal since 1755

" ''Journal of Accounting Historians,'' June 2003. *

External links

; EncyclopediasCorporatism

–

Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

Corporatism

–

The Canadian Encyclopedia

''The Canadian Encyclopedia'' (TCE; ) is the national encyclopedia of Canada, published online by the Toronto-based historical organization Historica Canada, with financial support by the federal Department of Canadian Heritage and Society of Com ...

; Articles

Professor Thayer Watkins, ''The economic system of corporatism''

,

San Jose State University

San José State University (San Jose State or SJSU) is a Public university, public research university in San Jose, California. Established in 1857, SJSU is the List of oldest schools in California, oldest public university on the West Coast of ...

, Department of Economics.

Chip Berlet, "Mussolini on the Corporate State"

2005, Political Research Associates. {{Authority control Collectivism Economic ideologies Fascism Political systems Political theories