Cornish Australians on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cornish Australians ( kw, Ostralians kernewek) are citizens of Australia who are fully or partially of Cornish heritage or descent, an ethnic group native to

Cornish food like the

Cornish food like the

There have been many other Australian politicians of Cornish birth or descent. Some of these are listed below, starting with perhaps the most important, Sir John Quick, Founding Father of the Australian Federation.

* John Quick – Postmaster-General, 1909–1910. Federal Member of Parliament for Bendigo, 1901–1913.

There have been many other Australian politicians of Cornish birth or descent. Some of these are listed below, starting with perhaps the most important, Sir John Quick, Founding Father of the Australian Federation.

* John Quick – Postmaster-General, 1909–1910. Federal Member of Parliament for Bendigo, 1901–1913.  *

*  *

*  *

*  *

*

Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

.

Cornish Australians form part of the worldwide Cornish diaspora

The Cornish diaspora ( kw, keskar kernewek) consists of Cornish people and their descendants who emigrated from Cornwall, United Kingdom. The diaspora is found within the United Kingdom, and in countries such as the United States, Canada, Austral ...

, which also includes large numbers of people in the US, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, New Zealand, South Africa, Mexico and many Latin American countries. Cornish Australians are thought to make up around 4.3 per cent of the Australian population and are thus one of the largest ethnic groups in Australia and as such are greater than the native population in the UK of just 532,300 (2011 census).

Cornish people first arrived in Australia with Captain Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

, most notably Zachary Hickes

Zachary Hicks (1739 – 25 May 1771) was a Royal Navy officer, second-in-command on Lieutenant James Cook's first voyage to the Pacific and the first among Cook's crew to sight mainland Australia. A dependable officer who had risen swiftly ...

, and there were some Cornish convicts on the First Fleet

The First Fleet was a fleet of 11 ships that brought the first European and African settlers to Australia. It was made up of two Royal Navy vessels, three store ships and six convict transports. On 13 May 1787 the fleet under the command ...

, James Ruse

James Ruse (9 August17595 September 1837) was a Cornish farmer who, at age 23, was convicted of burglary and was sentenced to seven years' transportation. He arrived at Sydney Cove, New South Wales, on the First Fleet with 18 months of h ...

, Mary Bryant

Mary Bryant (1765 – after 1794) was a Cornish convict sent to Australia. She became one of the first successful escapees from the fledgling Australian penal colony.

Early life

Bryant was born Mary Broad (referred to as Mary Braund at the E ...

, along with several of the early governors. The creation of South Australia, with its emphasis on being free of convicts and religious discrimination, was championed by many Cornish religious dissenting groups and Cornish people comprised a sizeable proportion of settlers to that colony. Large scale Cornish emigration to Australia did not begin until the 1840s, coinciding with the Cornish potato famine and slumps in the Cornish mining industry. The gold rushes and copper booms were major draws on Cornish people, not just from Cornwall itself, but also from other countries where they had previously settled.

In recent years the story of the ''Lost Children of Cornwall'', child migrants sent from Cornwall to Australia up until the early 1970s, has come under intense scrutiny. The practice of sending apparently unwanted or orphaned Cornish children abroad continued long after it had ceased, after being discredited, in other areas. It has been the subject of apologies by both the Australian and British prime ministers.

Number of Cornish Australians

A 1996 study by Dr. Charles Price gives the total ethnic strength of Cornish Australians as 269,500 with a total population of 768,100. This is made up by 22,600 of un-mixed origin and 745,500 of mixed origin and equates to 4.3 percent of the Australian population. This makes the Cornish the fourth largestAnglo-Celtic

Anglo-Celtic people are descended primarily from British and Irish people. The concept is mainly relevant outside of Great Britain and Ireland, particularly in Australia, but is also used in Canada, the United States, New Zealand and South Africa, ...

group in Australia after the English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

, Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

and Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

, and the fifth largest ethnic group in Australia.

Approximately 10 percent of the population of South Australia, and over 3 percent of Australia as a whole, has significant Cornish ancestry. In the 1986 Australian Census 15,000 people reported their ancestry as Cornish,Hale, Amy and Payton, Philip, New Directions in Celtic Studies, 2000 however, no figure from the 2006 Australian census has been published as to how many reported their ancestry as such in that year.

In 2011 a campaign was launched to increase the number of people writing in their Cornish ancestry on the 2011 Australian Census

The Census in Australia, officially the Census of Population and Housing, is the national census in Australia that occurs every five years. The census collects key demographic, social and economic data from all people in Australia on census nig ...

.

Culture

Festivals

The Cornish who moved to Australia brought with them many festivities and holidays. The most important being at Christmas and Midsummer.Payton, Philip, Making Moonta: The Invention of Australia's Little Cornwall * Christmas, amongst other things they would bring greenery inside their houses and sing their traditional carols. *Midsummer

Midsummer is a celebration of the season of summer usually held at a date around the summer solstice. It has pagan pre-Christian roots in Europe.

The undivided Christian Church designated June 24 as the feast day of the early Christian mart ...

, 24 June, was traditionally celebrated with fire. Cornish Australians used large amounts of fireworks, described as ''enough to bombard a town'', as well as numerous bonfires. It was observed as a general holiday with large numbers of community events also took place, including many sporting events, concerts, parades and tea-treats.

* The Duke of Cornwall

Duke of Cornwall is a title in the Peerage of England, traditionally held by the eldest son of the reigning British monarch, previously the English monarch. The duchy of Cornwall was the first duchy created in England and was established by a ro ...

's birthday was observed as a general holiday.

* Whit Monday

Whit Monday or Pentecost Monday, also known as Monday of the Holy Spirit, is the holiday celebrated the day after Pentecost, a moveable feast in the Christian liturgical calendar. It is moveable because it is determined by the date of Easter. I ...

was believed to be a more important celebration than the Queen's birthday.

* St Piran

Saint Piran or Pyran ( kw, Peran; la, Piranus), died c. 480,Patrons - The Orthodox Church of Archangel Michael and Holy Piran'' Oecumenical Patriarchate, Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain. Laity Moor, Nr Ponsanooth, Cornwall. TR3 7HR ...

's Day was celebrated during the early days in South Australia.

The Kernewek Lowender

The Kernewek Lowender (officially the Kernewek Lowender Copper Coast Cornish Festival) is a Cornish-themed biennial festival held in the Copper Coast towns of Kadina, Moonta and Wallaroo on Yorke Peninsula, South Australia. 'Kernewek Lowender' ...

( Cornish for "Cornish happiness"), held biennially since 1973 in the South Australian towns of Moonta, Kadina and Wallaroo

Wallaroo is a common name for several species of moderately large macropods, intermediate in size between the kangaroos and the wallabies. The word "wallaroo" is from the Dharug ''walaru'', and not a portmanteau of the words "kangaroo" and "wal ...

, is the largest Cornish festival in the world, attracting tens of thousands of visitors each year.

There have been four Cornish festivals held in the City of Bendigo

Bendigo ( ) is a city in Victoria, Australia, located in the Bendigo Valley near the geographical centre of the state and approximately north-west of Melbourne, the state capital.

As of 2019, Bendigo had an urban population of 100,991, makin ...

since 2002. The most recent was held at Eaglehawk

The wedge-tailed eagle (''Aquila audax'') is the largest bird of prey in the continent of Australia. It is also found in southern New Guinea to the north and is distributed as far south as the state of Tasmania. Adults of this species have lon ...

in March 2010 and was entitled 'Welcome Back Cousin Jack'(We welcome you 'One and All').

Food and drink

Cornish food like the

Cornish food like the Cornish pasty

A pasty () is a British baked pastry, a traditional variety of which is particularly associated with Cornwall, South West England, but has spread all over the British Isles. It is made by placing an uncooked filling, typically meat and vegetab ...

remains popular in Australia. Former premier of South Australia, Don Dunstan

Donald Allan Dunstan (21 September 1926 – 6 February 1999) was an Australian politician who served as the 35th premier of South Australia from 1967 to 1968, and again from 1970 to 1979. He was a member of the House of Assembly (MHA) for th ...

, once took part in a pasty-making contest. Swanky beer and saffron cake were very popular in the past and have been revitalised by Kernewek Lowender and the Cornish Associations.

In the 1880s Henry Madren Leggo, whose parents came from St Just, Cornwall, began making vinegar, pickles, sauces, cordials and other grocery goods based on his mother's traditional recipes. His company, now known as Leggo's, is wrongly believed by many to be Italian.

Angove Family Winemakers, formerly Angove's, was founded by Dr W.T. Angove, a Cornish doctor who migrated to South Australia with his family in 1886. He planted vines in the outer Adelaide suburb of Tea Tree Gully, though 125 years on most of its wines are based on Riverland grapes. They have recently started producing wines from their new vineyard purchased in 2002 in McLaren Vale. The distribution company wholesales not only Angove wines and St Agnes Brandy but also Nicolas Feuillatte Champagne and a dozen other companies' wines and spirits.

Matt Wilkinson of Pope Joan in Brunswick East, Melbourne, won the Southern Final of the Great Australian Sandwichship in 2011 with his lunch roll The Cornish which won an award in its category.

Language

The Cornish language is spoken by some enthusiasts in Australia. Members of theGorsedh Kernow

Gorsedh Kernow (Cornish Gorsedd) is a non-political Cornish organisation, based in Cornwall, United Kingdom, which exists to maintain the national Celtic spirit of Cornwall. It is based on the Welsh-based Gorsedd, which was founded by Iolo Mor ...

make frequent visits to Australia, and there are a number of Cornish Australian bards.

South Australian Aborigines

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait Islands ...

, particularly the Nunga

Nunga is a term of self-identification for Aboriginal Australians, originally used by Aboriginal people in the southern settled areas of South Australia, and now used throughout Adelaide and surrounding towns. It is used by contrast with ''Gu ...

, are said to speak English with a Cornish accent due to the fact that they were taught English by Cornish miners. Most large towns in South Australia had newspapers at least partially in Cornish dialect. At least 23 Cornish words have made their way into Australian English

Australian English (AusE, AusEng, AuE, AuEng, en-AU) is the set of varieties of the English language native to Australia. It is the country's common language and ''de facto'' national language; while Australia has no official language, Engli ...

, these include the mining terms ''fossick'' and ''nugget''.

Literature

''Not Only in Stone'' by Phyllis Somerville is the story of emigrant Cornishwoman, Polly Thomas, who faces many trials and tribulations in the pioneering era of South Australia. The book won the South Australian Centenary novel award in 1936. ''Kangaroo

Kangaroos are four marsupials from the family Macropodidae (macropods, meaning "large foot"). In common use the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, the red kangaroo, as well as the antilopine kangaroo, eastern gre ...

'' is D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English writer, novelist, poet and essayist. His works reflect on modernity, industrialization, sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. His best-k ...

's semi-autobiographical novel based on his wartime experiences in Cornwall and subsequent visit to Australia.

D. M. Thomas

Donald Michael Thomas (born 27 January 1935), is a British poet, translator, novelist, editor, biographer and playwright. His work has been translated into 30 languages.

Working primarily as a poet throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Thomas's 1981 ...

is an internationally renowned Cornish author who spent part of his childhood in Australia, drawing upon his experiences in his work.

Rosanne Hawke

Rosanne Hawke (born 1953) is an Australian author from Penola, South Australia who has written over 25 books for young adults and children. She teaches tertiary level creative writing (especially writing for children) at Tabor Adelaide. She has ...

is an author of children's books from Kapunda in South Australia.

Bruce Pascoe

Bruce Pascoe (born 1947) is an Aboriginal Australian writer of literary fiction, non-fiction, poetry, essays and children's literature. As well as his own name, Pascoe has written under the pen names Murray Gray and Leopold Glass. Since August 2 ...

, who challenged the colonial historical narrative in '' Dark Emu: Black Seeds, Agriculture or Accident?'', has both Cornish and Australian Aboriginal

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait Islands ...

(Bunurong

The Boonwurrung people are an Aboriginal people of the Kulin nation, who are the traditional owners of the land from the Werribee River to Wilsons Promontory in the Australian state of Victoria. Their territory includes part of what is now the c ...

, Yuin

The Yuin nation, also spelt Djuwin, is a group of Aboriginal Australians, Australian Aboriginal peoples from the South Coast (New South Wales), South Coast of New South Wales. All Yuin people share ancestors who spoke, as their first language, ...

and Tasmanian Aboriginal) roots.

''The Gommock. Exploits of a Cornish Fool in Colonial Australia.'' is a historical novel by Marie S. Jackman based around the lives of a Cornish emigrant miner Yestin Tregarthy and his wife Charlotte, set at the Burra Burra copper mine in South Australia.

Nobel Prize–winning author Patrick White

Patrick Victor Martindale White (28 May 1912 – 30 September 1990) was a British-born Australian writer who published 12 novels, three short-story collections, and eight plays, from 1935 to 1987.

White's fiction employs humour, florid prose, ...

wrote many novels with Cornish characters and themes. His fifth novel, ''Voss

Voss () is a municipality and a traditional district in Vestland county, Norway. The administrative center of the municipality is the village of Vossevangen. Other villages include Bolstadøyri, Borstrondi, Evanger, Kvitheim, Mjølfjell, Opphe ...

'', includes a character named Laura Trevelyan. ''A Fringe of Leaves

''A Fringe of Leaves'' is the tenth published novel by the Australian novelist and 1973 Nobel Prize-winner, Patrick White.

Plot

A young Cornish woman, Ellen Roxburgh, travels to the Australian colony of Van Diemen's Land (now "Tasmania") in ...

'' portrays Cornishwoman Ellen Roxburgh née Gluyas shipwrecked on an island and living amongst the aboriginal population.

The celebrated Australian poet John Blight

Frederick John Blight (30 July 1913 – 12 May 1995) was an Australian poet of Cornish origin, his ancestors having arrived in South Australia on the ''Lisander'', in 1851. In the 1987 recording ''John Blight'', he describes his Cornish backgro ...

's ancestors arrived in South Australia on the Lisander, in 1851. In the 1987 recording ''John Blight'' he describes his Cornish background and its influence on his style.

A true life character was George Hawke. He spent his early life working as a wool stapler for the Allanson family. He was born in St Eval

St Eval ( kw, S. Uvel) is a civil parish and hamlet in north Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The hamlet is about four miles (6.5 km) southwest of Padstow. The parish population at the 2011 census was 960.

Much of the village land was ac ...

Parish on 2 October 1802 at his father's farm near Bedruthan

Carnewas and Bedruthan Steps ( kw, Karn Havos, meaning "rock-pile of summer dwelling" and kw, Bos Rudhen, meaning "Red-one's dwelling") is a stretch of coastline located on the north Cornish coast between Padstow and Newquay, in Cornwall, Unit ...

. Following losses in an economic recession, George decided to emigrate to Australia. His words were recorded in a letter at age 70 years to a nephew back in Cornwall. The letter was later reproduced in full in Yvonne McBurney's book, ''The Road to Byng''.

Art

Oswald Pryor

Oswald Pryor (15 February 1881 – 13 June 1971) was a South Australian cartoonist noted for his depictions of life in the Copper Triangle, particularly of miners from Cornwall.

History

Oswald was born the son of James Pryor (c. 1844 – 19 Apri ...

(1881–1971) was a miner and cartoonist, born in Moonta and remembered for his humorous depictions of the lives of Cornish miners. Collections of his work include:

*Pryor, Oswald. ''Australia's little Cornwall'', Adelaide, S. Aust.: Rigby, 1962

*Pryor, Oswald. ''Cousin Jacks and Jennys'', Adelaide : Rigby, 1966

*Pryor, Oswald. ''Cornish pasty : a selection of cartoons'', Adelaide : Rigby, 1976

Roger Kemp

Francis Roderick Kemp AO, OBE, (Eaglehawk, 3 July 1908 - Melbourne 14 September 1987), known as Roger, was one of Australia's foremost practitioners of transcendental abstraction. Kemp developed a system of symbols and motifs which were deployed ...

– Abstractionist Painter

Music

Cornish Christmas carols are still traditionally sung in parts of Australia, just like inGrass Valley, California

Grass Valley is a city in Nevada County, California, United States. Situated at roughly in elevation in the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, this northern Gold Country city is by car from Sacramento, from Sacramento I ...

. Cornish Australians have a place in the transnational Cornish carol writing tradition. ''The Christmas Welcome: A Choice Collection of Cornish Carols,'' published at Moonta in 1893, was one of several such collections published between 1890 and 1925 from Polperro

Polperro ( kw, Porthpyra, meaning ''Pyra's cove'') is a large village, civil parish, and fishing harbour within the Polperro Heritage Coastline in south Cornwall, England. Its population is around 1,554.

Polperro, through which runs the River P ...

to Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Demo ...

. The Cornish also used to decorate their houses with greenery for Christmas, a tradition that was transported with them to Australia.

Cornish male voice choir

A men's chorus or male voice choir (MVC) (German: ''Männerchor''), is a choir consisting of men who sing with either a tenor or bass voice, and whose music is typically arranged into high and low tenors (1st and 2nd tenor), and high and low bass ...

s and brass bands were once a popular part of Cornish Australian culture, but this has waned somewhat. Religion

Many Cornish settlers in Australia wereMethodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

and many chapels were built in the places that they settled. Others were Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

, while few were Roman Catholic. Their Methodism was a badge of distinctive Cornishness and also gave them their trade unionist convictions. Most of the 22000 Wesleyan Methodists, 6000 Primitive Methodists and more than 6000 Bible Christians in South Australia in 1866 were Cornish.

Sport

There has been much involvement of Cornish Australians in sport over the years. Many playing rugby and cricket at an international level. This has led to the Cornish chant of "Oggie, Oggie, Oggie, Oi, Oi, Oi," taken on by all Australians as "Aussie, Aussie, Aussie." The Cornish took some of their own sports with them to Australia.Cornish wrestling

Cornish wrestling ( kw, Omdowl Kernewek) is a form of wrestling that has been established in Cornwall for many centuries and possibly longer. It is similar to the Breton Gouren wrestling style. It is colloquially known as "wrasslin’"Phillipps, ...

matches were a regular occurrence, held at festivities throughout the year, particularly Midsummer, Easter and Christmas. Thousands attended these contests, which were sometimes spread over several days and with wrestlers representing different mining regions. There were many Australian champion wrestlers and some of these competed internationally.

Politics

The Cornish miners founded the first trade unions, and were instrumental in the formation of theAustralian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms the f ...

. The first Labor party minority government in Tasmania (1909) was led by premier John Earle. The first Labor party majority government in South Australia (1910–12) was led by premier John Verran

John Verran (9 July 1856 – 7 June 1932) was an Australian politician and trade unionist. He served as premier of South Australia from 1910 to 1912, the second member of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) to hold the position.

Verran was b ...

, a Cornishman from Gwennap. The first Labor party majority government in Western Australia (1911–16) was led by premier John Scaddan

John Scaddan, CMG (4 August 1876 – 21 November 1934), popularly known as "Happy Jack", was Premier of Western Australia from 7 October 1911 until 27 July 1916.

Early life

John Scaddan was born in Moonta, South Australia, into a Cornish A ...

, a Cornishman from Moonta. Sir Robert Menzies founded the Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is a centre-right political party in Australia, one of the two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-left Australian Labor Party. It was founded in 1944 as the successor to the United Au ...

in 1944.

Heads of Government

Prime Ministers

Three of Australia's prime-ministers and one Acting prime Minister are known to have Cornish ancestry. *Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

, Australia's 12th

12 (twelve) is the natural number following 11 and preceding 13. Twelve is a superior highly composite number, divisible by 2, 3, 4, and 6.

It is the number of years required for an orbital period of Jupiter. It is central to many systems ...

and longest-serving Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, 1939–41 and again 1949–1966, was half Cornish. Meeting Cornish author A.L. Rowse

Alfred Leslie Rowse (4 December 1903 – 3 October 1997) was a British historian and writer, best known for his work on Elizabethan England and books relating to Cornwall.

Born in Cornwall and raised in modest circumstances, he was encoura ...

in Oxford once, he introduced himself as "a Cornish Sampson on his mother's side." His grandfather was the prominent Cornish trade unionist John Sampson.

* Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and union organiser who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (A ...

, 23rd Prime Minister of Australia and longest serving Australian Labor Party Prime Minister. Both of his parents were of Cornish ancestry. Hawke's leadership has been credited with reinvigorating academic interest in the Cornish in Australia.

* Scott Morrison

Scott John Morrison (; born 13 May 1968) is an Australian politician. He served as the 30th prime minister of Australia and as Leader of the Liberal Party of Australia from 2018 to 2022, and is currently the member of parliament (MP) for t ...

, Australia's Prime Minister between 2018 and 2022 confirmed he has Cornish ancestors when he visited Bodmin Jail

Bodmin Jail (alternatively Bodmin Gaol) is a historic former prison situated in Bodmin, on the edge of Bodmin Moor in Cornwall. Built in 1779 and closed in 1927, a large range of buildings fell into ruin, but parts of the prison have been tur ...

and St Keverne

St Keverne ( kw, Pluw Aghevran (parish), Lannaghevran (village)) is a civil parish and village on The Lizard in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom.

In addition to the parish, an electoral ward exists called ''St Keverne and Meneage''. This stre ...

in Cornwall during the G7 2021

The 47th G7 summit was held from 11 to 13 June 2021 in Cornwall, England, during the United Kingdom's tenure of the presidency of the Group of Seven (G7), an inter-governmental political forum of seven advanced nations.

The participants include ...

to research his family history.

Acting Prime Ministers

*George Pearce

Sir George Foster Pearce KCVO (14 January 1870 – 24 June 1952) was an Australian politician who served as a Senator for Western Australia from 1901 to 1938. He began his career in the Labor Party but later joined the National Labor Party, t ...

was acting prime minister for seven months in 1916 while Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

was overseas and remains the only Senator to have fulfilled the role of Prime Minister without resigning his Senate seat.

Premiers

Fourteen state premiers are known to have strong Cornish connections. At least sixPremiers of South Australia

The premier of South Australia is the head of government in the state of South Australia, Australia. The Government of South Australia follows the Westminster system, with a Parliament of South Australia acting as the legislature. The premier is ...

, and four Premiers of Western Australia

The premier of Western Australia is the head of government of the state of Western Australia. The role of premier at a state level is similar to the role of the prime minister of Australia at a federal level. The premier leads the executive bra ...

, have been of Cornish descent or birth.

=South Australia

= * George Waterhouse – 6thPremier of South Australia

The premier of South Australia is the head of government in the state of South Australia, Australia. The Government of South Australia follows the Westminster system, with a Parliament of South Australia acting as the legislature. The premier is ...

, 1861–1863. 7th Premier of New Zealand, 1872–1873. Born in Penzance

Penzance ( ; kw, Pennsans) is a town, civil parish and port in the Penwith district of Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is the most westerly major town in Cornwall and is about west-southwest of Plymouth and west-southwest of London. Situated ...

in 1824.

* James Penn Boucaut

Sir James Penn Boucaut (;) (29 October 1831 – 1 February 1916) was a South Australian politician and Australian judge. He was a member of the South Australian House of Assembly on four occasions: from 1861 to 1862 for City of Adelaide, from ...

– 11th Premier of South Australia. A judge and politician, Boucaut was Premier of South Australia three times: 1866–1867, 1875–1876 and 1877–1878. Born in Mylor in 1831, he emigrated to South Australia with his parents in 1846.

* John Verran

John Verran (9 July 1856 – 7 June 1932) was an Australian politician and trade unionist. He served as premier of South Australia from 1910 to 1912, the second member of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) to hold the position.

Verran was b ...

– 26th Premier of South Australia, 1910–1912. The 1910 election saw the South Australian division of the Australian Labor Party form a majority government, the first time a party had done so in South Australia. Verran was born at Gwennap in 1856 and when only three months old was taken by his parents to Australia. The family lived at Kapunda, South Australia, until he was eight, and then moved to Moonta where copper had been discovered in 1861.

* Robert Richards – 32nd Premier of South Australia, 1933. Born in Moonta in 1885, the youngest of twelve children to Cornish miner Richard Richards.

* Don Dunstan

Donald Allan Dunstan (21 September 1926 – 6 February 1999) was an Australian politician who served as the 35th premier of South Australia from 1967 to 1968, and again from 1970 to 1979. He was a member of the House of Assembly (MHA) for th ...

– 35th Premier of South Australia, 1967–1968 and again 1970–79. Born on 21 September 1926 in Suva, Fiji to Australian parents of Cornish descent. He played a crucial role in Labor's abandonment of the White Australia Policy, securing of Aboriginal rights and encouraging a more multi-cultural Australia. His socially progressive administration saw Aboriginal land rights recognised, homosexuality decriminalised, the first female judge appointed, the first non-British governor, Sir Mark Oliphant, and later, the first indigenous governor Douglas Nicholls.

* David Tonkin

David Oliver Tonkin AO (20 July 1929 – 2 October 2000) was an Australian politician who served as the 38th Premier of South Australia from 18 September 1979 to 10 November 1982. He was elected to the House of Assembly seat of Bragg at the 1 ...

– 38th Premier of South Australia, 1979–1982. Born in Adelaide in 1929.

=Western Australia

= *John Scaddan

John Scaddan, CMG (4 August 1876 – 21 November 1934), popularly known as "Happy Jack", was Premier of Western Australia from 7 October 1911 until 27 July 1916.

Early life

John Scaddan was born in Moonta, South Australia, into a Cornish A ...

– 10th Premier of Western Australia, 1911–1916. John Scaddan was born in Moonta in 1876, of a Cornish family. He led the first Labor party majority government in Western Australia. The hamlet of Scaddan located along the Esperance Branch Railway

The Esperance Branch Railway is a railway from Kalgoorlie to the port of Esperance in Western Australia.

It was lobbied for by Esperance residents to be linked into the WAGR railway network to provide land transport to their region.

In t ...

in the Goldfields-Esperance region of Western Australia is named after him.

* Albert Hawke

Albert Redvers George Hawke (3 December 1900 – 14 February 1986) was the 18th Premier of Western Australia. He served from 23 February 1953 to 2 April 1959, and represented the Labor Party.

Hawke was born in South Australia, and began ...

– 18th Premier of Western Australia, 1953–59. Born in 1900 to James Renfrey Hawke and Eliza Ann Blinman Pascoe, both of Cornish descent, in Kapunda, South Australia. He was uncle to Prime Minister Bob Hawke.

* David Brand

Sir David Brand KCMG (1 August 1912 – 15 April 1979) was an Australian politician. A member of the Liberal Party, he was a Member of the Legislative Assembly of Western Australia from 1945 to 1975, and also the 19th and longest-serving Premi ...

– 19th and longest serving Premier of Western Australia

The premier of Western Australia is the head of government of the state of Western Australia. The role of premier at a state level is similar to the role of the prime minister of Australia at a federal level. The premier leads the executive bra ...

, 1959–1971, grandson of Samuel Mitchell (1838–1912), who was born in Redruth, Cornwall, and established the mining industry in Western Australia, operating the state's first commercial mine, at Geraldine near Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England; ...

. He served in both houses of the Western Australian parliament

* John Trezise Tonkin – 20th Premier of Western Australia, 1971–74. Born in Boulder

In geology, a boulder (or rarely bowlder) is a rock fragment with size greater than in diameter. Smaller pieces are called cobbles and pebbles. While a boulder may be small enough to move or roll manually, others are extremely massive.

In c ...

in 1902. The stage 4 completion of the Beechboro-Gosnells Highway in 1985 saw the highway renamed Tonkin Highway

Tonkin Highway is an north–south highway and partial freeway in Perth, Western Australia, linking Perth Airport and Kewdale with the city's north-eastern and south-eastern suburbs. As of April 2020, the northern terminus is at the intercha ...

. Tonkin Bridge was also named after him shortly after his death at age 93.

=Tasmania

= *Edward Braddon

Sir Edward Nicholas Coventry Braddon (11 June 1829 – 2 February 1904) was an Australian politician who served as Premier of Tasmania from 1894 to 1899, and was a Member of the First Australian Parliament in the House of Representatives. Bradd ...

– 18th Premier of Tasmania

The premier of Tasmania is the head of the executive government in the Australian state of Tasmania. By convention, the leader of the party or political grouping which has majority support in the House of Assembly is invited by the governor of Ta ...

, 1894–1899. Braddon was born in St. Kew, Cornwall in 1829. He was a member of the First Australian Parliament in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

. Braddon was a Tasmanian delegate to the Constitutional Conventions. Both the suburb of Braddon in the Australian Capital Territory

The Australian Capital Territory (commonly abbreviated as ACT), known as the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) until 1938, is a landlocked federal territory of Australia containing the national capital Canberra and some surrounding townships. ...

and the Division of Braddon

The Division of Braddon is an Australian electoral division in the state of Tasmania. The current MP is Gavin Pearce of the Liberal Party, who was elected at the 2019 federal election.

Braddon is a rural electorate covering approximately ...

in Tasmania are named after him. His sister, Mary Elizabeth Braddon

Mary Elizabeth Braddon (4 October 1835 – 4 February 1915) was an English popular novelist of the Victorian era. She is best known for her 1862 sensation novel ''Lady Audley's Secret'', which has also been dramatised and filmed several times.

...

, was later a famous novelist.

* John Earle – 22nd Premier of Tasmania, 1909 and again 1914–1916. Born into a farming family of Cornish descent in Bridgewater, Tasmania

Bridgewater is a suburb of Hobart, Tasmania. Located approximately 19 km from the Hobart CBD, it is part of the northern suburbs area of Greater Hobart.

Overview

Bridgewater is situated on the eastern shore of the Derwent River. It is a ...

in 1865. He became Tasmania's first Labor premier, leading a minority government. He was Vice-President of the Executive Council

The Vice-President of the Executive Council is the minister in the Government of Australia who acts as the presiding officer of meetings of the Federal Executive Council when the Governor-General is absent. The Vice-President of the Executive ...

from 1921–1923.

=Queensland

= *Anna Bligh

Anna Maria Bligh (born 14 July 1960) is a lobbyist and former Australian politician who served as the 37th Premier of Queensland, in office from 2007 to 2012 as leader of the Labor Party. She was the first woman to hold either position. In 2 ...

– 37th Premier of Queensland

The premier of Queensland is the head of government in the Australian state of Queensland.

By convention the premier is the leader of the party with a parliamentary majority in the unicameral Legislative Assembly of Queensland. The premier is ap ...

, 2009–2012. Bligh describes herself as a descendant of Cornishman William Bligh. She was the first woman to be appointed Premier of Queensland and, at the 2009 Queensland State Election

The 2009 Queensland state election was held on 21 March 2009 to elect all 89 members of the Legislative Assembly, a unicameral parliament.

The election saw the incumbent Labor government led by Premier Anna Bligh defeat the Liberal National ...

, she became the first woman elected in her own right as a state premier in Australia. In 2009, Bligh was elected for three-year term to the three-person presidential team of the Australian Labor Party.

=Victoria

= *Albert Dunstan

Sir Albert Arthur Dunstan, KCMG (26 July 1882 – 14 April 1950) was an Australian politician. A member of the Country Party (now National Party), Dunstan was the 33rd premier of Victoria. His term as premier was the second-longest in th ...

– 33rd Premier of Victoria

The premier of Victoria is the head of government in the Australian state of Victoria. The premier is appointed by the governor of Victoria, and is the leader of the political party able to secure a majority in the Victorian Legislative Assembly ...

, 1935–1943 and again 1943–1945. Dunstan was born on 26 July 1882 at Donald East, Victoria, the son of a Cornish gold rush immigrant. He was the second longest serving Premier and the first to hold the position in its own right.

=Northern Territory

= *John Langdon Parsons

John Langdon Parsons (28 April 1837 – 21 August 1903), generally referred to as "J. Langdon Parsons", was a Cornish Australian minister of the Baptist church, politician, and the 5th Government Resident of the Northern Territory, 1884–1890 ...

– 5th Government Resident of the Northern Territory

The Administrator of the Northern Territory is an official appointed by the Governor-General of Australia to represent the government of the Commonwealth in the Northern Territory, Australia. They perform functions similar to those of a Governors ...

, 1884–1890. Member of the South Australian House of Assembly for Encounter Bay, 1878–1881, and North Adelaide 1881. Minister of education, 1881–84. He was the first Minister for the Northern Territory, 1890–93. He was instrumental in the development of railways in the Territory, and he also recognised Aboriginal land rights. Parsons was consul for Japan from 1896–1903. Member for the Central district in the Legislative Council, 1901–1903. Born on 28 April 1837 at Botathan near Launceston, Cornwall.

Other politicians

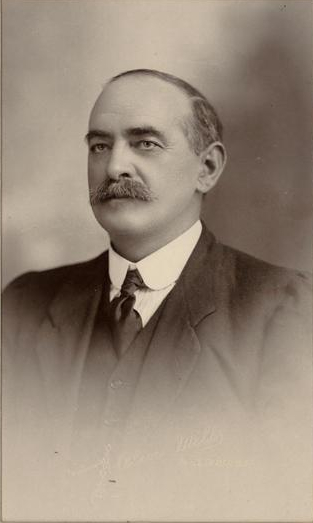

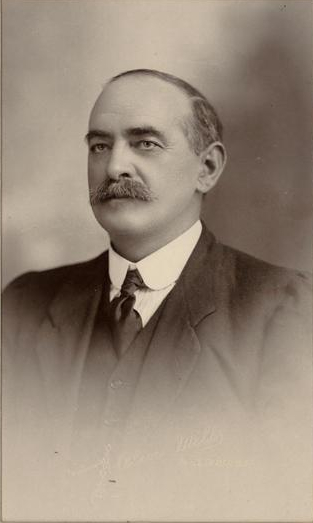

There have been many other Australian politicians of Cornish birth or descent. Some of these are listed below, starting with perhaps the most important, Sir John Quick, Founding Father of the Australian Federation.

* John Quick – Postmaster-General, 1909–1910. Federal Member of Parliament for Bendigo, 1901–1913.

There have been many other Australian politicians of Cornish birth or descent. Some of these are listed below, starting with perhaps the most important, Sir John Quick, Founding Father of the Australian Federation.

* John Quick – Postmaster-General, 1909–1910. Federal Member of Parliament for Bendigo, 1901–1913. Victorian Legislative Assembly

The Victorian Legislative Assembly is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Victoria in Australia; the upper house being the Victorian Legislative Council. Both houses sit at Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne.

The presiding ...

member for Bendigo, 1880–1889. He was a leading delegate to the constitutional conventions of the 1890s, proposing in August 1893 that a formal national convention should be established, with each of the six Australian colonies to be represented by ten elected delegates. The proposal was agreed on, and in November 1893 Quick drafted a bill which formed the basis of the deliberations at the formal convention held in Adelaide in 1897. He was born in Trevassa, Cornwall, in 1852. In 1913 Quick became the founding President of the first Bendigo Cornish Association.

* John Langdon Bonython

Sir John Langdon Bonython (;Charles Earle Funk, ''What's the Name, Please?'' (Funk & Wagnalls, 1936). 15 October 184822 October 1939) was an Australian editor, newspaper proprietor, philanthropist, journalist and politician who served a ...

– editor, newspaper proprietor, philanthropist, and journalist. Member of the First Australian Parliament. Member for South Australia, 1901–1903. Member for Barker, 1903–1906. Editor of the Adelaide daily morning broadsheet, The Advertiser, for 35 years.

* John Lavington Bonython

Sir John Lavington Bonython (10 September 1875 – 6 November 1960) was a prominent public figure in Adelaide, known for his work in journalism, business and politics. In association with his father, he became involved in the management of n ...

– Mayor of Adelaide, 1911–1913. Lord Mayor of Adelaide, 1927–1930. Son of John Langdon Bonython.

* Herbert Angas Parsons

Sir Herbert Angas Parsons, KBE, KC (23 May 1872 – 2 November 1945), generally known as Sir Angas Parsons, was a Cornish Australian lawyer, politician and judge.

Early life and education

Parsons was born in North Adelaide on 23 May 1872, ...

– judge and politician, son of politician John Langdon Parsons

John Langdon Parsons (28 April 1837 – 21 August 1903), generally referred to as "J. Langdon Parsons", was a Cornish Australian minister of the Baptist church, politician, and the 5th Government Resident of the Northern Territory, 1884–1890 ...

. Member of the House of Assembly for Torrens, 1912–15, and for Murray 1918–21. He was briefly attorney-general and minister of education in 1915. Parsons was appointed K.C. in 1916, a judge of the Supreme Court in 1921, he was senior puisne judge in 1927, and acting chief justice in 1935. On occasions Parsons acted as deputy governor and, after his father's death, in 1904 he became consul for Japan. President of the Cornish Association of South Australia, warden of the University of Adelaide's senate, and vice-chancellor from 1942–1944. Son in law of John Langdon Bonython.

* Garfield Barwick

Sir Garfield Edward John Barwick, (22 June 190313 July 1997) was an Australian judge who was the seventh and longest serving Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1964 to 1981. He had earlier been a Liberal Party politician, serving as a ...

– Attorney-General of Australia, 1958–64. Minister for External Affairs, 1961–64. Seventh and longest serving Chief Justice of Australia, 1964–81. He was appointed a judge of the International Court of Justice, 1973–74.

*

* John Pascoe Fawkner

John Pascoe Fawkner (20 October 1792 – 4 September 1869) was an early Australian pioneer, businessman and politician of Melbourne, Australia. In 1835 he financed a party of free settlers from Van Diemen's Land (now called Tasmania), to sail ...

– Founder of Melbourne. Member of the Victorian Legislative Council. His mother, Hannah Pascoe, was of Cornish parentage.

* John Gale – Father of Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

. Gale was the founder of the Queanbeyan Age

''The Queanbeyan Age'' is a weekly newspaper based in Queanbeyan, New South Wales, Australia. It has had a number of title changes throughout its publication history. First published on 15 September 1860 by John Gale and his brother, Peter F ...

newspaper. He is best remembered for his strong and successful advocacy of Queanbeyan-Canberra as the best site of a future Australian Capital. He was born in Bodmin

Bodmin () is a town and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated south-west of Bodmin Moor.

The extent of the civil parish corresponds fairly closely to that of the town so is mostly urban in character. It is bordere ...

in 1831.

* Ray Williams – Member for the Electoral district of Hawkesbury

Hawkesbury is an electoral district of the Legislative Assembly in the Australian state of New South Wales. It is represented by Robyn Preston of the Liberal Party.

It includes all of the City of Hawkesbury and the far north of both the Hill ...

in the New South Wales Parliament

The Parliament of New South Wales is a bicameral legislature in the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW), consisting of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly (lower house) and the New South Wales Legislative Council (upper house). Each ...

since 2007.

* George Laffer

George Richards Laffer (14 September 1866 – 7 December 1933) was an Australian politician. He was member of the South Australian House of Assembly from 1913 until 1933, representing the electorate of Alexandra for the Liberal Union, and its ...

– Member of the South Australian House of Assembly

The House of Assembly, or lower house, is one of the two chambers of the Parliament of South Australia. The other is the Legislative Council. It sits in Parliament House in the state capital, Adelaide.

Overview

The House of Assembly was creat ...

for Alexandra

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "prot ...

from 1913–1933. He was Speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** In ...

from 1927 until 1930.

* John Lutey

John Thomas Lutey (18 December 1876 – 22 June 1932) was the Labor Party member for the Western Australian Legislative Assembly seat of Brownhill-Ivanhoe from 1917 to 1932.

John Lutey was born on 18 December 1876 at Eaglehawk near Bendigo in ...

– Member for the Western Australian Legislative Assembly

The Western Australian Legislative Assembly, or lower house, is one of the two chambers of the Parliament of Western Australia, an Australian state. The Parliament sits in Parliament House in the Western Australian capital, Perth.

The Legisla ...

for Brownhill-Ivanhoe, 1917–1932.

* John Holman – Member for the Western Australian Legislative Assembly

The Western Australian Legislative Assembly, or lower house, is one of the two chambers of the Parliament of Western Australia, an Australian state. The Parliament sits in Parliament House in the Western Australian capital, Perth.

The Legisla ...

for North Murchison, 1901–1904. For the Electoral district of Murchison

Murchison-Eyre was an electoral district of the Legislative Assembly in the Australian state of Western Australia from 1890 to 1989 and again from 2005 to 2008.

Known as Murchison until 1968, it was one of the original 30 seats contested at t ...

, 1904–1921. For the Electoral district of Forrest

Forrest was an Electoral districts of Western Australia, electoral district of the Western Australian Legislative Assembly, Legislative Assembly in the Australian state of Western Australia from 1904 to 1950. It was based in the South West (Wes ...

, 1923–1925. His daughter, May, took over the Forrest seat after his death in 1925.

*

* May Holman

Mary Alice "May" Holman (18 July 1893 – 20 March 1939) was an Australian politician. She was a member of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and served in the Western Australian Legislative Assembly from 1925 until her death in 1939. She was th ...

– Member for the Western Australian Legislative Assembly

The Western Australian Legislative Assembly, or lower house, is one of the two chambers of the Parliament of Western Australia, an Australian state. The Parliament sits in Parliament House in the Western Australian capital, Perth.

The Legisla ...

for Forrest, 1925–1939. The daughter of John Holman, she was the second woman to be elected to an Australian parliament and the first female Labour parliamentarian. Holman was a delegate to the League of Nations Assembly in 1930. She died in a car crash on the day of her fourth re-election. Her brother took over the seat after her death.

* Richard Buzacott

Richard Buzacott (7 September 1867 – 10 January 1933), Australian politician, was a Member of the Australian Senate from 1910 to 1923.

Commonly known as Dick Buzacott, he was born at ''Emu Flat'', Clare, South Australia on 7 September 1867. ...

– Member of the Australian Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the Bicameralism, bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the House of Representatives (Australia), House of Representatives. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Chapter ...

for Western Australia, 1910–1923.

*

* Frederick Vosper

Frederick Charles Burleigh Vosper (23 March 1869 – 6 January 1901) was an Australian newspaper journalist and proprietor, and politician. He was well known for his ardent views and support of Australian republicanism, federalism and trade uni ...

– Member of the Western Australian Legislative Assembly for North-East Coolgardie, 1897–1900. Newspaper journalist and proprietor, he founded The Sunday Times (Western Australia)

''The Sunday Times'' is a tabloid Sunday newspaper published by Western Press Pty Ltd, a subsidiary of Seven West Media, in Perth and distributed throughout Western Australia. Founded as The West Australian Sunday Times, it was renamed The Su ...

. Born St. Dominic, Cornwall, in 1869.

* Henry Dangar

Henry Dangar (1796 - 1861) was a surveyor and explorer of Australia in the early period of British colonisation. He became a successful pastoralist and businessman, and also served as a magistrate and politician. He was born on 18 November 179 ...

– Pastoralist, surveyor and explorer of Australia. Member of the New South Wales Legislative Council for Northumberland, 1845–1851. By 1850 he owned or leased over 300,000 acres (121,406 ha). Born St Neot, Cornwall, in 1796.

* Mark Goldsworthy

Roger Mark Goldsworthy (born 24 September 1956) is an Australian politician who was the member for the electoral district of Kavel from 2002 to 2018, representing the Liberal Party.

Prior to his election into politics, Goldsworthy received an A ...

– Member of the South Australian House of Assembly for Kavel since 2002.

* Ian Trezise

Ian Douglas Trezise (born 30 September 1959) is an Australian politician. He was a Labor Party member of the Victorian Legislative Assembly from 1999 to 2014, representing the seat of Geelong.

Background

Trezise was born and raised in Geelon ...

– Member of the Victorian Legislative Council for Geelong, 1999– . Son of Neil Trezise.

* Baden Teague

Baden Chapman Teague (born 18 September 1944) served as a Liberal Senator for South Australia from 1977 until his retirement in 1996.

Born in Adelaide, Teague was educated at St. Peter’s College, the University of Adelaide and Cambridge Univ ...

– Senator for South Australia 1977–1996.

* Brice Mutton

Brice Mutton (8 January 1890 – 7 December 1949) was an Australian politician and a member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly for nine months in 1949. He was a member of the Liberal Party.

Early life

Mutton was born in Lerryn, Corn ...

– Member of the Parliament of New South Wales for Concord, 1949. Born Lerryn, Cornwall, in 1890.

* Tom Uren

Thomas Uren (28 May 1921 – 26 January 2015) was an Australian politician and Deputy Leader of the Australian Labor Party from 1975 to 1977. Uren served as the Member for Reid in the Australian House of Representatives from 1958 to 1990, bei ...

– Member of the Parliament of Australia for Reid, 1958–1990. Various Ministerial roles during the 1970s and 80s. Father of the House of Representatives, 1984–1990. Deputy Leader of the Australian Labor Party, 1975–1977.

* Nick Champion

Nicholas David Champion (born 27 February 1972) is an Australian politician. He is a member of the South Australian Labor Party and has served in the South Australian House of Assembly since the 2022 South Australian state election, representi ...

– Member of the Australian House of Representatives for Wakefield

Wakefield is a cathedral city in West Yorkshire, England located on the River Calder. The city had a population of 99,251 in the 2011 census.https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/census/2011/ks101ew Census 2011 table KS101EW Usual resident population, ...

from 2007 until 2019, then member for Spence.

* Robert Brokenshire

Robert Lawrence Brokenshire (born 1957) is a South Australian dairy farmer and former member of the South Australian Parliament. He represented the Australian Conservatives from 26 April 2017 to election defeat in 2018, and Family First Party ...

– Member of the South Australian Parliament for Mawson

Sir Douglas Mawson OBE FRS FAA (5 May 1882 – 14 October 1958) was an Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer, and academic. Along with Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, and Sir Ernest Shackleton, he was a key expedition leader durin ...

, 1993–2006. Member of the South Australian Legislative Council for the Family First Party

The Family First Party was a Conservatism in Australia, conservative political party in Australia which existed from 2002 to 2017. It was founded in South Australia where it enjoyed its greatest electoral support. Since the demise of the Austral ...

since 2008.

* Neil Trezise

Neil Benjamin "Nipper" Trezise (8 February 1931 – 20 August 2006) was an Australian rules footballer who represented in the Victorian Football League and later a politician who represented the Labor Party in the Victorian Legislative Assem ...

– Player and captain for Geelong Football Club

The Geelong Football Club, nicknamed the Cats, is a professional Australian rules football club based in Geelong, Victoria, Australia. The club competes in the Australian Football League (AFL), the sport's premier competition, and are the 2022 ...

. Member of the Victorian Legislative Council for Geelong West, 1964–1967, and again for Geelong North, 1967–1992.

* Bob Chynoweth

Robert Leslie Chynoweth (born 7 June 1941) is an Australian politician. He was an Australian Labor Party member of the Australian House of Representatives from 1983 to 1990 and again from 1993 to 1996.

Chynoweth was born in Richmond, an inner s ...

– Member of the Australian Parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislature, legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the ...

for Flinders

Flinders may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Flinders Peak, near the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula

Australia New South Wales

* Flinders County, New South Wales

* Shellharbour Junction railway station, Shellharbour

* Flinders, New South Wa ...

, 1983–1984. Member of the Australian Parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislature, legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the ...

for Dunkley, 1984–1990, and again 1993–96.

*

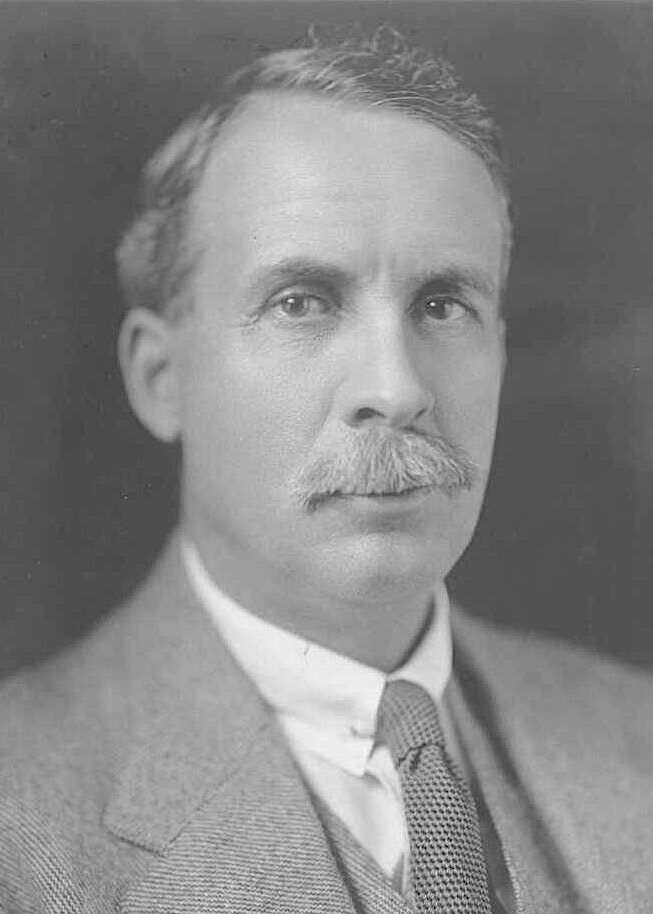

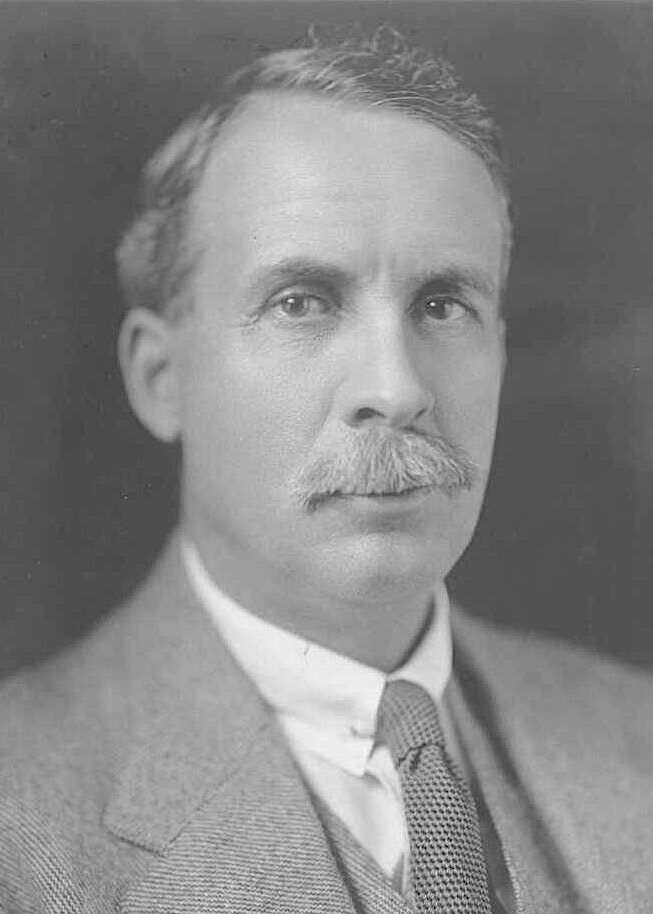

* George Pearce

Sir George Foster Pearce KCVO (14 January 1870 – 24 June 1952) was an Australian politician who served as a Senator for Western Australia from 1901 to 1938. He began his career in the Labor Party but later joined the National Labor Party, t ...

– Senator for Western Australia, 1901–1938. Instrumental in founding the Australian Labor Party in Western Australia. Minister for Defence, 1908–1909, 1910–1913, 1914–1921 and again in 1932–1934. Vice-President of the Executive Council, 1926–1929. Various other Ministerial roles during the 1920s and 1930s. Deputy Leader of the Australian Labor Party, 1915–1916. Leader of the Australian Labor Party in the Senate, 1914–1916. Leader of the National Labor Party

The National Labor Party was formed by Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes in 1916, following the 1916 Labor split on the issue of World War I conscription in Australia. Hughes had taken over as leader of the Australian Labor Party and Pri ...

in the Senate, 1916–1917. Leader of the Nationalist Party in the Senate, 1917–1931. Leader of the United Australia Party

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four federal elections in that time, usually governing in coalition with the Country Party. It provided two prim ...

in the Senate, 1931–1937.

* Josiah Thomas – Member of the Australian Parliament for Barrier, 1901–1917. Senator for New South Wales, 1917–1923 and again 1