Corn-Law Rhymer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ebenezer Elliott (17 March 1781 – 1 December 1849) was an English poet, known as the ''Corn Law rhymer'' for his leading the fight to repeal the

Ebenezer Elliott (17 March 1781 – 1 December 1849) was an English poet, known as the ''Corn Law rhymer'' for his leading the fight to repeal the

One of Elliott's last poems, "The People's Anthem", first appeared in Tait's ''

One of Elliott's last poems, "The People's Anthem", first appeared in Tait's ''

Ebenezer Elliott site.

/ref> That same year the new Wetherspoons pub in Rotherham was named 'The Corn Law Rhymer', and in March 2013 a blue plaque commemorating the poet was placed on the town's medical walk-in centre, marking the site of the iron foundry where he was born.

The Poetical Works of Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn-law Rhymer

Edinburgh 1840 *

''Rotherhamweb ''

biography & selected writings at gerald-massey.org.uk * * * *Archival material at {{DEFAULTSORT:Elliott, Ebenezer 1781 births 1849 deaths Chartists Foundrymen History of Sheffield People from Rotherham English male poets People educated at Penistone Grammar School 19th-century English poets

Ebenezer Elliott (17 March 1781 – 1 December 1849) was an English poet, known as the ''Corn Law rhymer'' for his leading the fight to repeal the

Ebenezer Elliott (17 March 1781 – 1 December 1849) was an English poet, known as the ''Corn Law rhymer'' for his leading the fight to repeal the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. The la ...

, which were causing hardship and starvation among the poor. Though a factory owner himself, his single-minded devotion to the welfare of the labouring classes won him a sympathetic reputation long after his poetry ceased to be read.

Early life

Elliott was born at the New Foundry,Masbrough

Masbrough is a suburb of Rotherham, South Yorkshire, England. It was named as the west of Rotherham by the middle of the Industrial Revolution, namely that part on the left bank of River Don, South Yorkshire, Don. Historic counties of England, ...

, in the parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christianity, Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest#Christianity, priest, often termed a parish pries ...

of Rotherham

Rotherham ( ) is a market town in South Yorkshire, England. It lies at the confluence of the River Rother, South Yorkshire, River Rother, from which the town gets its name, and the River Don, Yorkshire, River Don. It is the largest settlement ...

, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

. His father, known as "Devil Elliott" for his fiery sermons, was an extreme Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

and a strong Radical

Radical (from Latin: ', root) may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Classical radicalism, the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and Latin America in the 19th century

*Radical politics ...

. He was engaged in the iron trade. His mother suffered from poor health, and young Ebenezer, although one of eleven children, of whom eight reached maturity, had a solitary and rather morbid childhood. At the age of six he contracted smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

, which left him "fearfully disfigured and six weeks blind". His health was permanently affected, and he suffered from illness and depression in later life.

He was first educated at a dame school

Dame schools were small, privately run schools for children aged two to five. They emerged in Great Britain and its colonies during the Early modern Britain, early modern period. These schools were taught by a “school dame,” a local woman ...

, then at the Hollis School in Rotherham, where he was "taught to write and little more", but was generally regarded as a dunce

''Dunce'' is a mild insult in English meaning "a person who is slow at learning or stupid". The etymology given by Richard Stanyhurst is that the word is derived from the name of the Scottish scholastic theologian and philosopher John Duns Scot ...

. Moving to Thurlstone

Thurlstone is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Penistone, in the metropolitan borough of Barnsley (borough), Barnsley, in South Yorkshire, England. Originally it was a small farming community. Some industries developed u ...

in 1790, he attended Penistone Grammar School

Penistone Grammar School (PGS) is a large co-educational secondary school with a sixth form located in Penistone, South Yorkshire, England.

Founded in 1392, it is amongst the List of the oldest schools in the United Kingdom, oldest extant scho ...

. He hated school and preferred to play truant, spending his time exploring the countryside, observing the plants and local wildlife. At the age of 14 he began to read extensively on his own account, and in his leisure hours he studied botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

, collected plants and flowers, and was delighted by the appearance of "a beautiful green snake about a yard long, which on the fine Sabbath mornings about ten o'clock seemed to expect me at the top of Primrose Lane." When he was 16 he was sent to work at his father's foundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

, where he received only a little pocket money in lieu of wages for the next seven years.

Early works

In a fragment ofautobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life, providing a personal narrative that reflects on the author's experiences, memories, and insights. This genre allows individuals to share thei ...

printed in '' The Athenaeum'' (12 January 1850) he says that he was entirely self-taught, and attributes his poetic development to long country walks undertaken in search of wild flowers, and to a collection of books, including the works of Edward Young

Edward Young ( – 5 April 1765) was an English poet, best remembered for ''Night-Thoughts'', a series of philosophical writings in blank verse, reflecting his state of mind following several bereavements. It was one of the most popular poem ...

, Isaac Barrow

Isaac Barrow (October 1630 – 4 May 1677) was an English Christian theologian and mathematician who is generally given credit for his early role in the development of infinitesimal calculus; in particular, for proof of the fundamental theorem ...

, William Shenstone

William Shenstone (18 November 171411 February 1763) was an English poet and one of the earliest practitioners of History of gardening#Picturesque and English Landscape gardens, landscape gardening through the development of his estate, ''The ...

and John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, and civil servant. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'' was written in blank verse and included 12 books, written in a time of immense religious flux and politic ...

, bequeathed to his father. His son-in-law, John Watkins, gave a more detailed account in "The Life, Poetry and Letters of Ebenezer Elliott", published in 1850. One Sunday morning, after a heavy night's drinking, Elliott missed chapel

A chapel (from , a diminutive of ''cappa'', meaning "little cape") is a Christianity, Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. First, smaller spaces inside a church that have their o ...

and visited his Aunt Robinson, where he was enthralled by some colour plates of flowers from James Sowerby

James Sowerby (21 March 1757 – 25 October 1822) was an English natural history, naturalist, illustrator and mineralogist. Contributions to published works, such as ''A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland'' or ''English Botany'', include his ...

's ''English Botany''. When his aunt encouraged him to make his own flower drawings, he was pleased to find he had a flair for it. His younger brother, Giles, whom he had always admired, read him a poem from James Thomson's " The Seasons", which described polyanthus and auricular flowers, and this was a turning point in Elliott's life. He realised he could successfully combine his love of nature, and his talent for drawing, by writing poems and decorating them with flower illustrations.

In 1798, aged 17, he wrote his first poem, "Vernal Walk", in imitation of James Thompson. He was also influenced by George Crabbe

George Crabbe ( ; 24 December 1754 – 3 February 1832) was an English poet, surgeon and clergyman. He is best known for his early use of the realistic narrative form and his descriptions of middle and working-class life and people.

In the 177 ...

, Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

and the Romantic poets

Romantic poetry is the poetry of the Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. It involved a reaction against prevailing Neoclassical ideas of the 18th c ...

and Robert Southey

Robert Southey (; 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic poetry, Romantic school, and Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth an ...

, who later became Poet Laureate. In 1808 Elliott wrote to Southey asking for advice on getting published. Southey's welcome reply began a correspondence over the years that reinforced his determination to make a name for himself as a poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator (thought, thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral t ...

. They only met once, but exchanged letters until 1824, and Elliott declared it was Southey who had taught him the art of poetry.

Other early poems were ''Second Nuptials and Night, or the Legend of Wharncliffe'', which was described by the ''Monthly Review'' as the "''Ne plus ultra'' of German horror and bombast". His ''Tales of the Night'', including ''The Exile'' and ''Bothwell'', were considered to be of more merit and brought him commendations. His earlier volumes of poems, dealing with romantic themes, received much unfriendly comment, and the faults of ''Night'', the earliest of these, were pointed out in a long and friendly letter (30 January 1819) from Southey to the author.

Elliott had married Frances (Fanny) Gartside in 1806, and they eventually had 13 children. He invested his wife's fortune in his father's share of the iron foundry, but the affairs of the family firm were then in a desperate condition, and money difficulties hastened his father's death. Elliott lost everything and went bankrupt in 1816. In 1819 he obtained funds from his wife's sisters, and began another business as an iron dealer in Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, situated south of Leeds and east of Manchester. The city is the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire and some of its so ...

. This prospered, and by 1829 he had become a successful iron merchant and steel manufacturer.

Political activity

When made bankrupt, Elliott had been homeless and out of work, facing starvation and contemplating suicide. He always identified with the poor. He remained bitter about his earlier failure, attributing his father's pecuniary losses and his own to the operation of theCorn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. The la ...

, whose repeal became the greatest issue in his life.

Elliott became well known in Sheffield for his strident views on changes that would improve conditions for both manufacturers and workers, but was often disliked on this account by his fellow entrepreneurs. He formed the first society in England to call for reform of the Corn Laws: the Sheffield Mechanics' Anti-Bread Tax Society founded in 1830. Four years later, he was behind the establishment of the Sheffield Anti-Corn Law Society and the Sheffield Mechanics' Institute

Mechanics' institutes, also known as mechanics' institutions, sometimes simply known as institutes, and also called schools of arts (especially in the Australian colonies), were educational establishments originally formed to provide adult edu ...

. He was also very active in the Sheffield Political Union

The Sheffield Political Union (SPU) was an organisation established to campaign for Parliamentary Reform in Sheffield, England. It attracted 12,000 members in 1832.

The SPU was founded by "Eleven Poor Men of Hallamshire" as celebrated in a hymn o ...

and campaigned vigorously for the Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the Reform Act 1832, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. 4. c. 45), enacted by the Whig government of Pri ...

( 2 & 3 Will. 4. c. 45). He was later active in Chartist agitation, acting as the Sheffield delegate to the Great Public Meeting in Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

in 1838, and chairing the meeting in Sheffield where the Charter was introduced to local people. However, Elliott withdrew from the Sheffield organisation after the Chartist Movement advocated the use of violence.

The strength of his political convictions was reflected in the style and tenor of his verse, earning him the nickname of "the Corn Law Rhymer", and making him internationally famous. After a single long poem, "The Ranter", in 1830, came the ''Corn Law Rhymes'' in 1831. Inspired by a hatred of injustice, the poems were vigorous, simple and full of vivid description and campaigned politically against the landowners in the government who stifled competition and kept the price of bread high. They also heeded the dreadful conditions endured by working people and contrasted their lot with that of the complacent gentry

Gentry (from Old French , from ) are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past. ''Gentry'', in its widest connotation, refers to people of good social position connected to Landed property, landed es ...

. He went on to publish a three-volume set of the growing number of his works in ''The Splendid Village; Corn-Law Rhymes, and other Poems'' (1833–1835), which included "The Village Patriarch" (1829), "The Ranter", "Keronah" and other pieces.

The ''Corn Law Rhymes'' marked a shift away from the long narratives that had preceded them, towards verses for singing that would carry a wider message to the labouring class. Several of the poems indicate the tune for them (including the Marseillaise

"La Marseillaise" is the national anthem of France. It was written in 1792 by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle in Strasbourg after the declaration of war by the First French Republic against Austria, and was originally titled "".

The French Nati ...

) and one late poem at least, "They say I'm old because I'm grey", was set to music by a local composer. He followed up the ''Rhymes'' of 1831 with the ''Corn Law Hymns'' of 1835, which are even more belligerent and political in spirit:

:::The locustry of Britain

:::Are gods beneath the skies;

:::They stamp the brave into the grave;

:::They feed on Famine's sighs.

His poems by then were being published in the United States and in Europe. The French magazine ''Le Revue des deux Mondes'' sent a journalist to Sheffield to interview him. The ''Corn Law Rhymes'' were initially thought to be written by an uneducated Sheffield mechanic

A mechanic is a skilled tradesperson who uses tools to build, maintain, or repair machinery, especially engines. Formerly, the term meant any member of the handicraft trades, but by the early 20th century, it had come to mean one who works w ...

, who had rejected conventional Romantic ideals for a new style of working-class poetry aimed at changing the system. Elliott was described as "a red son of the furnace", and called "the Yorkshire Burns

Burns may refer to:

Astronomy

* 2708 Burns, an asteroid

* Burns (crater), on Mercury

People

* Burns (surname), list of people and characters named Burns

** Burns (musician), Scottish record producer

Places in the United States

* Burns, ...

" or "the Burns of the manufacturing city". The French journalist was surprised to find Elliott a mild man with a nervous temperament.

One of Elliott's last poems, "The People's Anthem", first appeared in Tait's ''

One of Elliott's last poems, "The People's Anthem", first appeared in Tait's ''Edinburgh Review

The ''Edinburgh Review'' is the title of four distinct intellectual and cultural magazines. The best known, longest-lasting, and most influential of the four was the third, which was published regularly from 1802 to 1929.

''Edinburgh Review'', ...

'' in 1848. It was written for music and usually sung to the tune "Commonwealth".

:::When wilt thou save the people?

:::Oh, God of mercy! when?

:::Not kings and lords, but nations!

:::Not thrones and crowns, but men!

:::Flowers of thy heart, oh, God, are they!

:::Let them not pass, like weeds, away!

:::Their heritage a sunless day!

:::God! save the people!

The final refrain parodies the British national anthem

A national anthem is a patriotic musical composition symbolizing and evoking eulogies of the history and traditions of a country or nation. The majority of national anthems are marches or hymns in style. American, Central Asian, and European ...

, ''God Save the Queen

"God Save the King" ("God Save the Queen" when the monarch is female) is '' de facto'' the national anthem of the United Kingdom. It is one of two national anthems of New Zealand and the royal anthem of the Isle of Man, Australia, Canada and ...

'', and demands support for ordinary people instead. Despite its huge popularity, some churches refused to use hymn books which contained it, as it could also be seen as a criticism of God. In his notes on the poem, Elliott demanded that votes be given to all responsible householders. The poem remained a favourite for many years, and in the 1920s it was suggested it had qualified Elliott to be Poet Laureate of the League of Nations.

The words of "The People's Anthem" eventually entered the American Episcopal hymn-book. From that source it was included, along with others, in the rock musical ''Godspell

''Godspell'' is a musical in two acts with music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz and a book by John-Michael Tebelak. The show is structured as a series of parables, primarily based on the Gospel of Matthew, interspersed with music mostly set t ...

'' (1971), in which it was retitled "Save the People", with a new musical score.

Literary friendships

Elliott's relations with like-minded writers remained close, particularly with James Montgomery and John Holland, both of whom espoused other humanitarian causes. He was also sympathetic to labouring-class poets and is recorded as being over-generous in his praise of the fledgling writing that they brought to show him. For reasons of propriety, Mary Hutton addressed herself to Mrs Elliott, although she also addresses the poet himself in one stanza of the poem of condolence she wrote on the death of two of their children. The Elliott family were subscribers to her next collection, which is dedicated to Mrs Elliott, in thanks for her sympathy and help. Another writer with whom he became friendly when he moved to Sheffield in 1833 was the former shoemaker Paul Rodgers, who for a time became secretary of the Sheffield Mechanics' Institution. He was later to head the campaign to raise subscriptions for a statue in Elliott's memory and wrote a memoir of him after his death. He also relates there how Elliott befriended the lecturer and writer Charles Reece Pemberton and helped to raise a subscription to support him when his health broke down. The two went on a walk together in 1838, after which Elliott recorded his impressions of "Roch Abbey", praising and characterising his companion. Elliott paid Peterson a further tribute in his poem "Poor Charles" after Pemberton's death two years later. Elliot's "Song" beginning "Here's a health to our friends of reform", mentions several poets among the political agitators for theReform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the Reform Act 1832, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. 4. c. 45), enacted by the Whig government of Pri ...

, the passing of which it celebrates. Among the surnames enumerated is that of Thomas Asline Ward

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

(1781–1871), leader of the Sheffield Political Union and editor of the ''Sheffield Independent''. Also present is Reverend Jacob Brettel, a Unitarian minister in Rotherham who had published the poem "A Country Minister" (1825), and ''Sketches in verse, from the historical books of the Old Testament'' (1828). A further reference is to "Holland the fearless and pure". This was not John Holland but George Calvert Holland

George Calvert Holland (28 February 1801 – 7 March 1865) was an English physician, phrenologist, mesmerist and homeopath. In later life he was active in politics and the railway boom.

Life

Holland was born 28 February 1801 at Pitsmoor, Sheffi ...

(1801–1865), to whom Elliott's long early poem "Love" was dedicated. Of labouring-class origin, he had educated himself to become a Sheffield surgeon. Elliott's first attempt at a sonnet was also inscribed "To G. C. Holland, M.D."; it was followed by a light-hearted "Epistle to G. C. Holland, Esq., M.D." on women's emancipation.

In the case of Thomas Lister (1810–1888) from nearby Barnsley, we are granted insight into an example of poetic dialogue. Elliott wrote two poems entitled "To Thomas Lister". One is a stirring exhortation to take a high theme in his poetry, the other a humorous exercise in hexameter

Hexameter is a metrical line of verses consisting of six feet (a "foot" here is the pulse, or major accent, of words in an English line of poetry; in Greek as well as in Latin a "foot" is not an accent, but describes various combinations of s ...

s marking the measure as "in English undignified, loose, and worse than the worst prose", in response to verses sent him by Lister. In 1837 Lister addressed a sonnet to Elliott "From the summit of Ben Ledi" while on a walking tour in Scotland.

Final years and death

In 1837 Elliott's business suffered from the trade recession of that year, but he still had enough money to retire in 1841 and settle on land he had bought at Great Houghton, nearBarnsley

Barnsley () is a market town in South Yorkshire, England. It is the main settlement of the Metropolitan Borough of Barnsley and the fourth largest settlement in South Yorkshire. The town's population was 71,422 in 2021, while the wider boroug ...

. There he lived quietly, seeing the Corn Laws repealed in 1846, and dying in 1849, aged 68. He was buried in the churchyard of All Saints Church, Darfield.

Earlier in his life, Elliott had written "A Poet's Epitaph", setting out the poetic programme for which he wished to be remembered:

::Stop, Mortal! Here thy brother lies,

::The Poet of the Poor

::His books were rivers, woods and skies,

::The meadow and the moor,

::His teachers were the torn hearts’ wail,

::The tyrant, and the slave,

::The street, the factory, the jail,

::The palace – and the grave!

News of his death brought poetic tributes: the Chartist George Tweddell (1823–1903) devoted three sonnets to him. Another Chartist who had recently become his son-in-law, John Watkins (1809–1858), described the poet's last moments in "On The Death of Ebenezer Elliott". Still another tribute with the same title came from the labouring-class poet, John Critchley Prince

John Critchley Prince (1808–1866) was an English labouring-class poet. His ''Hours of the Muses'' went through six editions.

Life

Born at Wigan, Lancashire, on 21 June 1808, Prince was the son of a poor reed-maker for weavers. He learned to read ...

, in his "Poetic Rosary" (1850) Though honouring him as "No trifling, tinkling, moon-struck Bard" and "The proud, unpensioned Laureate of the Poor", it also acknowledged the elemental violence of his writing. The American poet John Greenleaf Whittier

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the fireside poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet ...

's poem "Elliott", on the other hand, is as forceful as the Englishman had been, forbidding the capitalist "locust swarm that cursed the harvest-fields of God" to have a hand in his burial:

::Then let the poor man's horny hands

::Bear up the mighty dead,

::And labor's swart and stalwart bands

::Behind as mourners tread.

::Leave cant and craft their baptized bounds,

::Leave rank its minster floor;

::Give England's green and daisied grounds

::The poet of the poor!

News of a monument to the poet to be erected in 1854 was greeted by a tribute from Walter Savage Landor

Walter Savage Landor (30 January 177517 September 1864) was an English writer, poet, and activist. His best known works were the prose ''Imaginary Conversations,'' and the poem "Rose Aylmer," but the critical acclaim he received from contempora ...

to "The Statue of Ebenezer Elliott by Neville Burnard, (ordered by the working men of Sheffield)", celebrating the poet and praising the city for its enterprise, in a muscular poem of radical force. Once the bronze statue was in place in Sheffield market place, the blade-maker Joseph Senior (1819–1892) made it the subject of an unrhymed sonnet, "Lines on Ebenezer Elliott's Monument". Hailing the "sullen pile of hard-won toilers' pence", and equally sceptical of the work of "moon-struck bards", he addressed the poet as one who "by song more hungry Britons fed/ Than all the lyric sons that ever sang".

A long prose account of Elliott had appeared two years before his death in ''Homes and Haunts of the Most Eminent British Poets'' by William Howitt (1792–1879). Howitt had visited Elliott in 1846 to interview him for the article, where he praised the depictions of nature in Elliott's earlier poems rather than the rant of his political work. After his death, Elliott's obituary appeared in the ''Gentleman's Magazine'' in February 1850. Two biographies also appeared that year, one by John Watkins and another, ''The Life, Character and Genius of Ebenezer Elliott'', by January Searle (George Searle Phillips). Two years later, Searle followed his book up with ''Memoirs of Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn Law Rhymer''. A new edition of Elliott's works by his son Edwin appeared in 1876.

Legacy

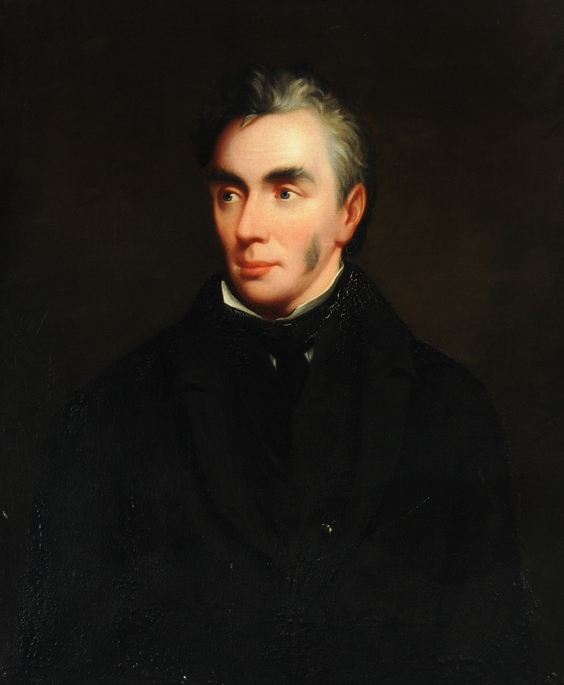

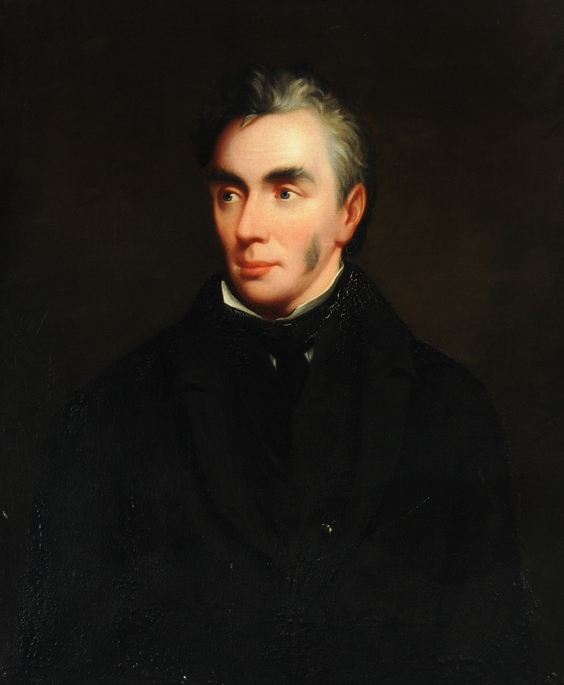

Paul Rodgers gave the opinion that Elliott "has been sorely handled by the painters and engravers.... The published portraits convey scarcely any idea at all of the man." Of those that remain, two have been attributed to John Birch, who also painted other Sheffield worthies. One shows him seated with a scroll in his left hand and spectacles dangling from the right. The other has him seated on a boulder, clasping an open book in his lap, with the narrow valley of Black Brook in the background. This spot above theRiver Rivelin

The River Rivelin is a river in Sheffield, South Yorkshire, England.

It rises on the Hallam moors, in north west Sheffield, and joins the River Loxley (at Malin Bridge). The Rivelin Valley, through which the river flows, is a long woodland vall ...

was a favourite of Elliott's, and he is said to have carved his name on a boulder there. A drawing of Elliott by the Scottish artist Margaret Gillies is now in the National Portrait Gallery, London

The National Portrait Gallery (NPG) is an art gallery in London that houses a collection of portraits of historically important and famous British people. When it opened in 1856, it was arguably the first national public gallery in the world th ...

. She had accompanied William Howitt in 1847 when he visited the poet for another interview, and her work was reproduced to illustrate it in ''Howitt's Journal''. Another seated portrait, book in lap, "may be a better picture", thought Rodgers, "but is still less like him."

Elliott is seated on a rock in Neville Burnard's statue of him, which was also thought a poor likeness. In its issue on 22 July 1854, ''The Sheffield Independent'' reported that "Many of the persons in Sheffield who have a vivid remembrance of the features of Ebenezer Elliott will feel disappointed that, in this case, the sculptor had not given a more exact similitude of the man as he lived", but goes on to surmise that this is meant to be a "somewhat idealised representation of the Corn Law Rhymer". In 1875, the work was removed from the city centre to Weston Park

Weston Park is a country house in Weston-under-Lizard, Staffordshire, England, set in more than of park landscaped by Capability Brown. The park is located north-west of Wolverhampton, and east of Telford, close to the border with Shropshire ...

, where it remains.

The statue figures no more clearly in John Betjeman

Sir John Betjeman, (; 28 August 190619 May 1984) was an English poet, writer, and broadcaster. He was Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death. He was a founding member of The Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architect ...

's poem "An Edwardian Sunday, Broomhill, Sheffield". "Your own Ebenezer", he apostrophizes, "Looks down from his height/ On back street and alley/ And chemical valley", which he certainly does not. The poet's final city dwelling in 1834–1841 was in Upperthorpe, not Broomhill, and bears a blue plaque today. Furthermore, the inscription on the pedestal reads simply "Elliott", with no mention of his given name. This is noted, among others, by the Sheffield poet Stanley Cook (1922–1991) in his tribute to the relocated statue. "It was not this dog's convenience wrote the poems", he comments, "But a man could be put together from passers-by" still angry at remaining injustices.

Rotherham, Elliott's birthplace, was slower to honour him. In 2009 a work by Martin Heron was erected on what is now known as Rhymer's Roundabout, near Rotherham. Entitled "Harvest", it depicts stylised ears of corn blowing in the wind, as an allusion to the "Corn Law Rhymes"./ref> That same year the new Wetherspoons pub in Rotherham was named 'The Corn Law Rhymer', and in March 2013 a blue plaque commemorating the poet was placed on the town's medical walk-in centre, marking the site of the iron foundry where he was born.

References

Attribution: * *Sources

*Keith Morris & Ray Hearne, ''Ebenezer Elliott: Corn Law Rhymer & Poet of the Poor'', Rotherwood Press, Oct 2002, *The Life, Poetry and Letters of Ebenezer Elliott", by John Watkins, pub. 1850The Poetical Works of Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn-law Rhymer

Edinburgh 1840 *

External links

''Rotherhamweb ''

biography & selected writings at gerald-massey.org.uk * * * *Archival material at {{DEFAULTSORT:Elliott, Ebenezer 1781 births 1849 deaths Chartists Foundrymen History of Sheffield People from Rotherham English male poets People educated at Penistone Grammar School 19th-century English poets