Corder Catchpool on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas "Corder" Pettifor Catchpool (15 July 1883 – 16 September 1952), born Leicester, was an English

Thomas "Corder" Pettifor Catchpool (15 July 1883 – 16 September 1952), born Leicester, was an English

Thomas "Corder" Pettifor Catchpool (15 July 1883 – 16 September 1952), born Leicester, was an English

Thomas "Corder" Pettifor Catchpool (15 July 1883 – 16 September 1952), born Leicester, was an English Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

and pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaig ...

, actively engaged in relief work in Germany between 1919 and 1952. He was awarded the French Mons Star

The 1914 Star, colloquially known as the Mons Star, is a British World War I campaign medal for service in France or Belgium between 5 August and 22 November 1914.

Institution

The 1914 Star was authorised under Special Army Order no. 350 in Nov ...

for his relief work with the Friends Ambulance Unit

The Friends' Ambulance Unit (FAU) was a volunteer ambulance service, founded by individual members of the British Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), in line with their Peace Testimony. The FAU operated from 1914–1919, 1939–1946 and 1946 ...

on the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

*Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a majo ...

(1914–1916), subsequently imprisoned in Britain for his absolutist conscientious objection to the Compulsory Military Service Act 1916. After the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

he was released from prison and critical of the implications of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

, played an active role in reconciliation with Germany: in 1919 he assisted with the Friends War Victims Relief Committee in Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

, an organisation that was involved in organising the feeding of up to one million children per day. Returning to Britain he worked as a welfare coordinator for a Lancashire firm at Darwen, and was responsible for the invitation to Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

to visit the mill to witness the impact of the nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

campaign on conditions.

Between 1931 and 1936 Catchpool worked out of the Friends International Centre in Berlin to assist those who were victims of anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

and other Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hit ...

policies. His goal from 1933 onwards was "the prevention of progressive German isolation that could only lead to war". He was arrested by the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one or ...

in 1933 and temporarily detained, and he, his family and the Quaker German Yearly Meeting were subject to ongoing surveillance and intimidation. Demonstrating his concern for human rights extended to all people, Catchpool also embarked on several missions to campaign for minority Germans who were being deprived of their civil rights in Memelland in Lithuania, and Sudetanland in Czechoslovakia. For his latter work, Catchpool received the Czech Order of the White Line, fourth class (Officer), "for the magnificent work you have done as representative of the Society of Friends to alleviate the sufferings of children in the distressed areas of Czechoslovakia."

As an active member of the Peace Pledge Union during the Second World War, Catchpool joined secular pacifist Vera Brittain

Vera Mary Brittain (29 December 1893 – 29 March 1970) was an English Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse, writer, feminist, socialist and pacifist. Her best-selling 1933 memoir '' Testament of Youth'' recounted her experiences during the Firs ...

, non-pacifist Professor Stanley Jevons and others in setting up the Bombing Restriction Committee in 1942. The Committee called upon both Britain and Germany to stop the terror bombing of civilian targets, specifically urging the British government "to stop violating their declared policy of bombing only military objectives, and particularly to cease causing the deaths of many thousands of civilians in their homes."

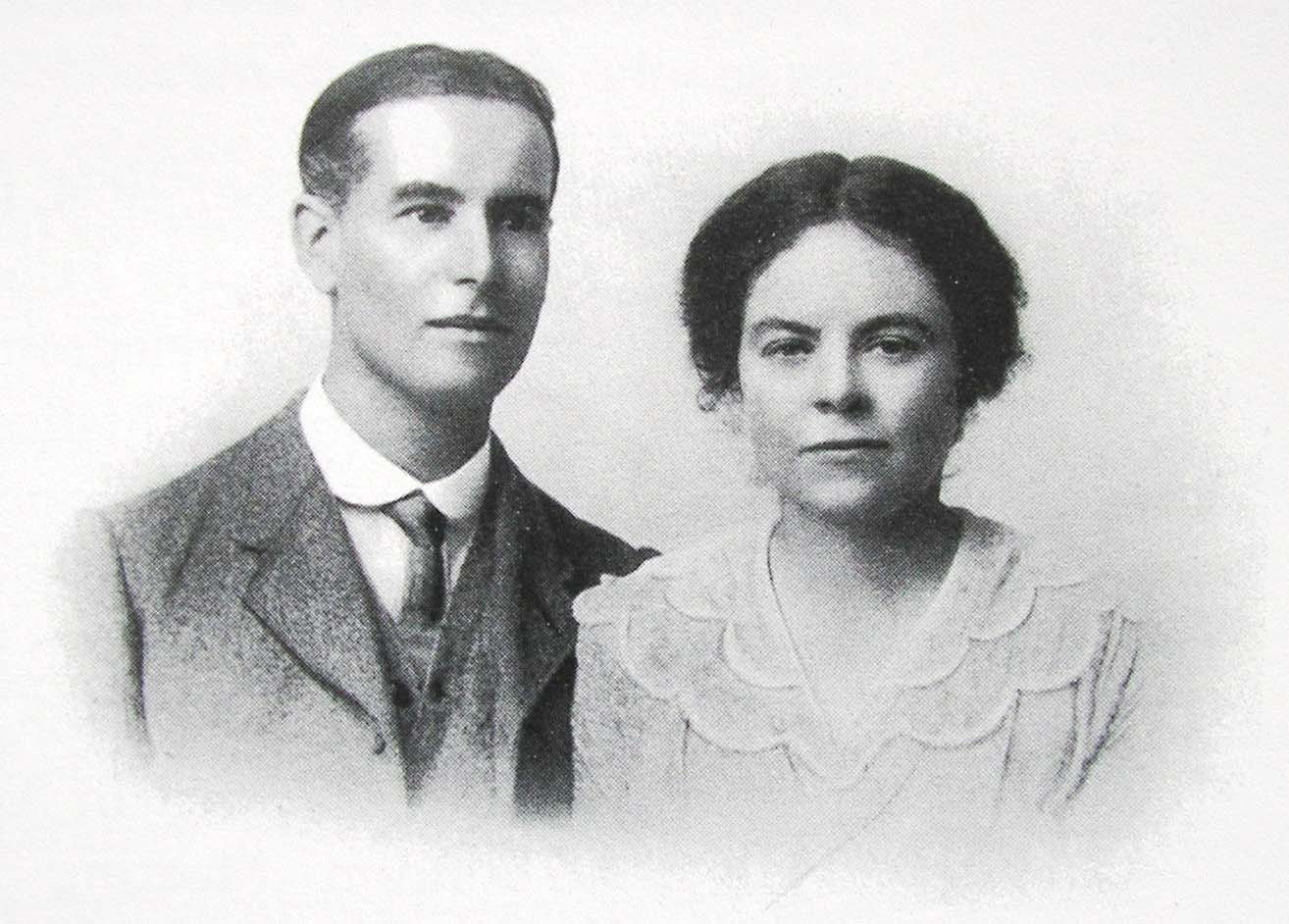

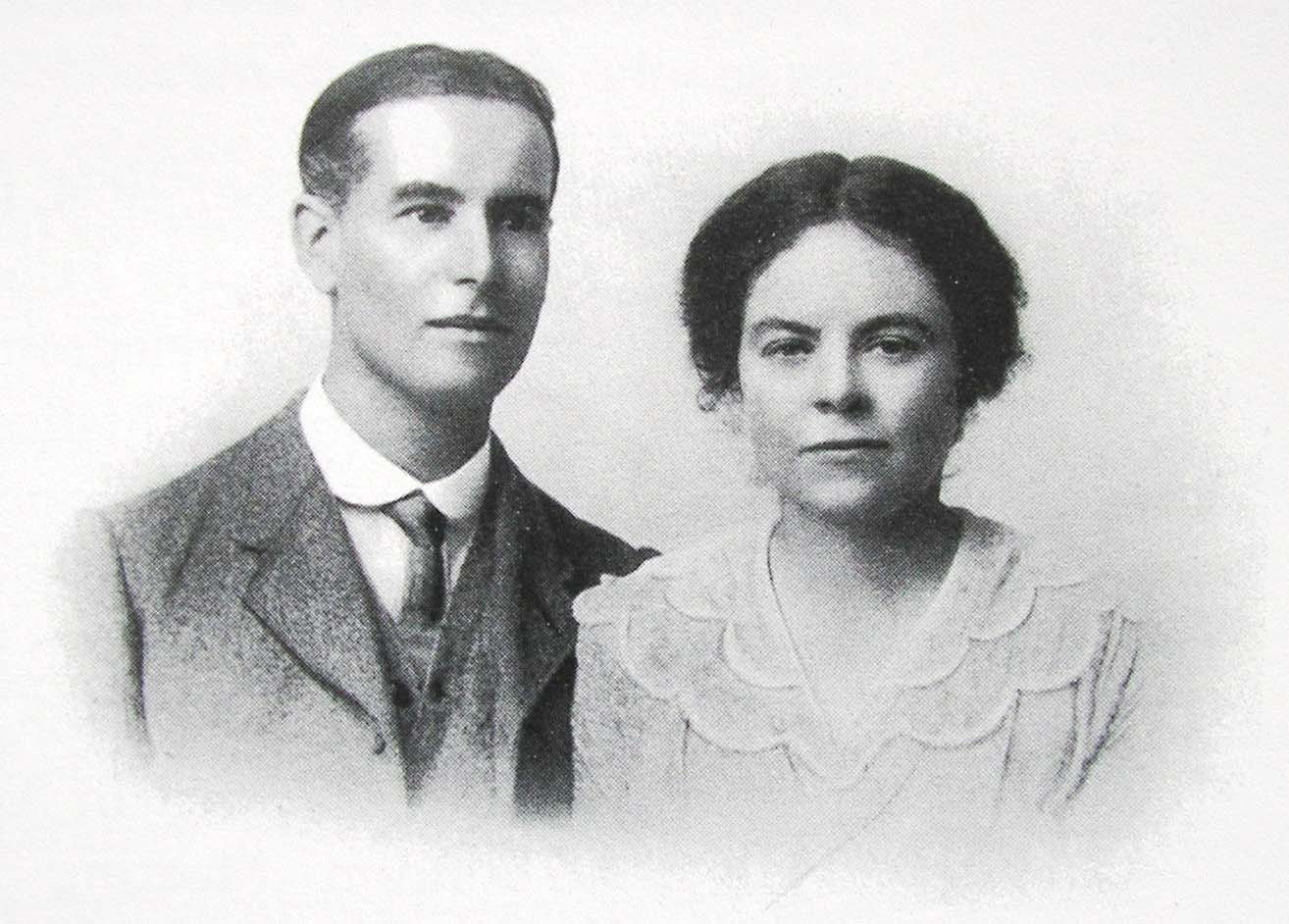

In 1946, Catchpool returned to Germany to do relief work and in 1947, he and his wife Gwen were invited by the Friends Relief Service

The Friends Relief Service (FRS) was a voluntary humanitarian relief organisation formally established by a committee of Britain Yearly Meeting in November 1940. Largely staffed by pacifists and conscientious objectors, its aim was to provide hu ...

to run the Quaker Rest Home for ex-prisoners of the Nazis at Bad Pyrmont in Germany. During 1950 and 1951, Gwen and Catchpool represented the Friends Service Committee in West Berlin.

Catchpool was educated in schools in Leicester and Sidcot Friends' School, and at Bootham School

Bootham School is an independent Quaker boarding school, on Bootham in the city of York in England. It accepts boys and girls ages 3–19, and had an enrolment of 605 pupils in 2016. It is one of seven Quaker schools in England.

The scho ...

. He raised four children with his wife Gwen (née Southall) who played an active part in his work.

An avid alpine climber, Corder Catchpool died in a mountaineering accident on Dufourspitze

, it, Punta Dufour, rm, Piz da Dufour

, translation = Peak Dufour, Highest Peak, Large Horn

, photo = Monte Rosa summit.jpg

, photo_size =

, photo_caption = From the peak to the southeast towards Italy, the Dunantspi ...

, Switzerland, in 1952.

His younger brother was Jack Catchpool.

References

*Corder Catchpool, "On Two Fronts: Letters of a Conscientious Objector." 1919. * William R. Hughes, "Indomitable Friend: The life of Corder Catchpool 1883-1952". London, Housmans, 1956. * Hans A. Schmitt. "Quakers and Nazis: inner light in outer darkness." Columbia, MO, University of Missouri, 1997.External links

* Corder Catchpool, Collected Papers, Swarthmore College Peace collection at http://www.swarthmore.edu/library/peace/CDGB/Catchpool.html * {{DEFAULTSORT:Catchpool, Corder 1883 births 1952 deaths English Christian pacifists English conscientious objectors English Quakers Mountaineering deaths Sport deaths in Switzerland People from Leicester