Coors Strike And Boycott on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Coors strike and boycott was a series of

The Coors strike and boycott was a series of

Another point of contention between the company and protestors involved the use of

Another point of contention between the company and protestors involved the use of

In 1976, under Colorado's Labor Peace Law provisions, Coors demanded a vote amongst brewery workers on whether the brewery would remain a

In 1976, under Colorado's Labor Peace Law provisions, Coors demanded a vote amongst brewery workers on whether the brewery would remain a

In 1986, the South Dakota Farmers Union announced they would also be boycotting Coors following advertisements Coors released that the union said cast aspersions on local

In 1986, the South Dakota Farmers Union announced they would also be boycotting Coors following advertisements Coors released that the union said cast aspersions on local

The Coors strike and boycott was a series of

The Coors strike and boycott was a series of boycotts

A boycott is an act of nonviolent resistance, nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organisation, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for Morality, moral, society, social, politics, political, or Environmenta ...

and strike action

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to Working class, work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Str ...

against the Coors Brewing Company

The Coors Brewing Company is an American brewery and beer company based in Golden, Colorado, that was founded in 1873. In 2005, Adolph Coors Company, the holding company that owned Coors Brewing, merged with Molson, Inc. to become Molson Coor ...

, based in Golden, Colorado

Golden is a home rule city that is the county seat of Jefferson County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 20,399 at the 2020 United States census. Golden lies along Clear Creek at the base of the Front Range of the Rocky Moun ...

, United States. Initially local, the boycott started in the late 1960s and continued through the 1970s, coinciding with a labor strike at the company's brewery in 1977. The strike ended the following year in failure for the union, which Coors forced to dissolve. The boycott, however, lasted until the mid-1980s, when it was more or less ended.

The boycott began in 1966 as a regional affair coordinated by the Colorado chapter of the American GI Forum

The American GI Forum (AGIF) is a congressionally chartered Hispanic veterans and civil rights organization founded in 1948. Its motto is "Education is Our Freedom and Freedom should be Everybody's Business". AGIF operates chapters throughout ...

and the Denver-based Crusade for Justice. These two Hispanic

The term Hispanic () are people, Spanish culture, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or broadly. In some contexts, Hispanic and Latino Americans, especially within the United States, "Hispanic" is used as an Ethnici ...

groups initiated a boycott due to the Coors Brewing Company's discriminatory practices that targeted Hispanics and African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

. Additionally, they opposed the Coors family's support of right wing political causes. Soon afterward, the boycott expanded through much of the American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Western States, the Far West, the Western territories, and the West) is census regions United States Census Bureau

As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the mea ...

. By the 1970s, the boycott covered much of Coors' market area and involved Hispanic, African American, and women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and Entitlement (fair division), entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st c ...

groups, as well as labor unions

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

and LGBT activists

A list of notable LGBTQ rights activists who have worked to advance LGBTQ rights by political change, legal action or publication. Ordered by country, alphabetically.

Albania

* Xheni Karaj, founder of Aleanca LGBT organization and recipien ...

. The latter group opposed Coors' practice of using a polygraph

A polygraph, often incorrectly referred to as a lie detector test, is a pseudoscientific device or procedure that measures and records several physiological indicators such as blood pressure, pulse, respiration, and skin conductivity while a ...

test during their hiring process, which they alleged allowed them to discriminate against LGBT individuals. In San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, the city's LGBT community and the Teamsters

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) is a trade union, labor union in the United States and Canada. Formed in 1903 by the merger of the Team Drivers International Union and the Teamsters National Union, the union now represents a di ...

union allied to promote the boycott that involved noted gay rights activist Harvey Milk

Harvey Bernard Milk (May 22, 1930 – November 27, 1978) was an American politician and the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California, as a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.

Milk was born and raised i ...

.

In April 1977, members of Brewery Workers

A brewery or brewing company is a business that makes and sells beer. The place at which beer is commercially made is either called a brewery or a beerhouse, where distinct sets of brewing equipment are called plant. The commercial brewing of be ...

Local 366, which represented over 1,500 workers at the company's flagship Golden, Colorado brewery, went on strike over noneconomic issues related to, among other things, the company's use of polygraph testing and their 21 grounds for dismissal. Shortly after the strike started, the AFL-CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) is a national trade union center that is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 61 national and international unions, together r ...

(the United States' largest federation of labor unions) initiated a nationwide boycott of Coors. The strike lasted for over 20 months, during which time a majority of the union members went back to work without a contract after the company began replacing strikers with strikebreakers

A strikebreaker (sometimes pejoratively called a scab, blackleg, bootlicker, blackguard or knobstick) is a person who works despite an ongoing strike. Strikebreakers may be current employees ( union members or not), or new hires to keep the org ...

. The company initiated a vote the following year over whether the local union would be dissolved, with a majority of workers voting to dissolve Brewery Workers Local 366. Despite this, the AFL–CIO continued their boycott. By the 1980s, Coors began making deals with several minority groups to do more business with minority companies and hire more minority workers. Despite this, the boycott continued and expanded to include numerous other groups, such as the National Organization for Women

The National Organization for Women (NOW) is an American feminist organization. Founded in 1966, it is legally a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization. The organization consists of 550 chapters in all 50 U.S. states and in Washington, D.C. It ...

and the National Education Association

The National Education Association (NEA) is the largest labor union in the United States. It represents public school teachers and other support personnel, faculty and staffers at colleges and universities, retired educators, and college st ...

. However, in August 1987, the AFL–CIO agreed to end the boycott, with Coors making several concessions that included using union labor to build a new facility in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

and an agreement to an expedited union vote at its Golden facility. In December 1988, workers at the Golden brewery voted against unionizing by a margin of over 2 to 1.

The strike and boycott had a direct economic impact on Coors. The company's market share in several western states dropped from over 40 percent to as low as 17 percent in the case of California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

. Additionally, the boycott may have encouraged the company to expand nationally, as the company expanded its presence from 11 states in 1975 to 49 states by 1988. In the LGBT community, the boycott left a lasting impact, as several groups and activists still object to Coors over the company's past actions and the family's continued support of conservative politics. As late as 2019, Coors beer was difficult to find in any gay bar

A gay bar is a Bar (establishment), drinking establishment that caters to an exclusively or predominantly lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ+) clientele; the term ''gay'' is used as a broadly inclusive concept for LGBTQ+ communi ...

in San Francisco.

Background

Coors and organized labor

TheCoors Brewing Company

The Coors Brewing Company is an American brewery and beer company based in Golden, Colorado, that was founded in 1873. In 2005, Adolph Coors Company, the holding company that owned Coors Brewing, merged with Molson, Inc. to become Molson Coor ...

is a Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

-based brewing company

A brewery or brewing company is a business that makes and sells beer. The place at which beer is commercially made is either called a brewery or a beerhouse, where distinct sets of brewing equipment are called plant. The commercial brewing of b ...

that was founded in 1873 by German American

German Americans (, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry.

According to the United States Census Bureau's figures from 2022, German Americans make up roughly 41 million people in the US, which is approximately 12% of the pop ...

Adolph Coors

Adolph Herman Joseph Coors Sr. (February 4, 1847 – June 5, 1929) was a German-American brewer who founded the Adolph Coors Company in Golden, Colorado, in 1873.

Early life

Adolph Hermann Joseph Kuhrs was born in Barmen in Rhenish Prus ...

. By 1975, it had grown to become the fourth-largest brewing company in the United States, and its brewery in Golden, Colorado

Golden is a home rule city that is the county seat of Jefferson County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 20,399 at the 2020 United States census. Golden lies along Clear Creek at the base of the Front Range of the Rocky Moun ...

was the single largest brewing facility in the world. That year, the company did approximately $440 million in sales. Its product was notable at the time for being one of the few beers created in the United States not to be pasteurized

In food processing, pasteurization ( also pasteurisation) is a process of food preservation in which packaged foods (e.g., milk and fruit juices) are treated with mild heat, usually to less than , to eliminate pathogens and extend shelf life ...

, which required the beer to be constantly refrigerated to prevent going stale. The company was also notable for only selling its products in 11 states in the American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Western States, the Far West, the Western territories, and the West) is census regions United States Census Bureau

As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the mea ...

, as opposed to the national distribution of its main competitors: Anheuser-Busch

Anheuser-Busch Companies, LLC ( ) is an American brewing company headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri. Since 2008, it has been wholly owned by Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV (AB InBev), now the world's largest brewing company, which owns multiple ...

, the Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company

Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company is an United States, American brewery based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and was once the largest producer of beer in the United States. Its namesake beer, Schlitz (), was known as "The beer that made Milwaukee famous" ...

, and the Pabst Brewing Company

The Pabst Brewing Company () is an American company that dates its origins to a brewing company founded in 1844 by Jacob Best and was, by 1889, named after Frederick Pabst. It outsources the brewing of over two dozen brands of beer and ma ...

. This limited market area led to considerable bootlegging of the product to the eastern United States

The Eastern United States, often abbreviated as simply the East, is a macroregion of the United States located to the east of the Mississippi River. It includes 17–26 states and Washington, D.C., the national capital.

As of 2011, the Eastern ...

. Organized labor

The labour movement is the collective organisation of working people to further their shared political and economic interests. It consists of the trade union or labour union movement, as well as political parties of labour. It can be considere ...

activities at the brewery began in the 1930s, when Adolph Coors II

Adolph Herman Joseph Coors Jr. (January 12, 1884 – June 28, 1970) was an American businessman. He was the son of Louisa (Webber) and brewer Adolph Coors, and the second President of Coors Brewing Company.

Life and career

Coors was a graduate ...

(who had succeeded his father as chief of the company) invited a labor union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

to organize at the location. However, in the following decades, the company had a troubled relationship with organized labor, with the AFL–CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) is a national trade union center that is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 61 national and international unions, together r ...

claiming that the company had destroyed 19 different unions at their facilities, including local union

A local union (often shortened to local), in North America, or union branch (known as a lodge in some unions), in the United Kingdom and other countries, is a local branch (or chapter) of a usually national trade union. The terms used for sub-bran ...

s representing boilermaker

A boilermaker is a Tradesman, tradesperson who Metal fabrication, fabricates steels, iron, or copper into boilers and other large containers intended to hold hot gas or liquid, as well as maintains and repairs boilers and boiler systems.Bure ...

s, electrician

An electrician is a tradesman, tradesperson specializing in electrical wiring of buildings, transmission lines, stationary machines, and related equipment. Electricians may be employed in the installation of new electrical components or the ...

s, and ironworker

An ironworker is a tradesman who works in the iron-working industry. Ironworkers assemble the structural framework in accordance with engineered drawings and install the metal support pieces for new buildings. They also repair and renovate o ...

s, among other groups.

The Coors family and social issues

By 1975, several members of the Coors family held leadership positions in the company, includingExecutive Vice President

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

Joseph Coors

Joseph Coors Sr. (November 12, 1917 – March 15, 2003), was the grandson of brewer Adolph Coors and president of Coors Brewing Company.

Early life and education

Coors was born on November 12, 1917, in Golden, Colorado, to Alice May Kistler ...

and Chairman of the Board

The chair, also chairman, chairwoman, or chairperson, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a Board of directors, board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by ...

William Coors

William Kistler Coors (August 11, 1916 – October 13, 2018) was an American brewery executive with the Coors Brewing Company. He was affiliated with the company for over 64 years, and was a board member from 1973 to 2003. He was a grandson of Ad ...

, both grandsons of Adolph's. The family was well known for their support of conservative political causes, with Joseph in particular described by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' as an "ultraconservative zealot". During the late 1960s to early 1970s, Joseph served as a member of the Regents of the University of Colorado

The Regents of the University of Colorado is the governing board of the University of Colorado system, the system of public universities in the U.S. state of Colorado. Established under Article IX, Section 12 of the Constitution of Colorado, it ha ...

, during which time he took a hardline stance against student activism

Student activism or campus activism is work by students to cause political, environmental, economic, or social change. In addition to education, student groups often play central roles in democratization and winning civil rights.

Modern stu ...

. He also opposed the creation of a chapter of the United Mexican American Students on campus, as well as the creation of courses

Course may refer to:

Directions or navigation

* Course (navigation), the path of travel

* Course (orienteering), a series of control points visited by orienteers during a competition, marked with red/white flags in the terrain, and corresponding ...

regarding Chicana/o studies. Contemporary regents, from both the Democratic and Republican Parties, criticized Coors' actions as regent. In 1974, he was nominated by U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

to the board of directors

A board of directors is a governing body that supervises the activities of a business, a nonprofit organization, or a government agency.

The powers, duties, and responsibilities of a board of directors are determined by government regulatio ...

for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting

The Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB; stylized as cpb) is an American publicly funded non-profit corporation, created in 1967 to promote and help support public broadcasting. The corporation's mission is to ensure universal access to ...

. However, his nomination was later killed by the U.S. Senate Commerce Committee, which expressed concerns over potential conflicts of interest

A conflict of interest (COI) is a situation in which a person or organization is involved in multiple interests, financial or otherwise, and serving one interest could involve working against another. Typically, this relates to situations in whi ...

after it was revealed that he had donated money to the John Birch Society

The John Birch Society (JBS) is an American right-wing political advocacy group. Founded in 1958, it is anti-communist, supports social conservatism, and is associated with ultraconservative, radical right, far-right, right-wing populist, and ...

. Joseph later donated money towards Ronald Reagan's 1976 presidential campaign, and he additionally provided grants and funding to conservatives groups including The Heritage Foundation

The Heritage Foundation (or simply Heritage) is an American Conservatism in the United States, conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C. Founded in 1973, it took a leading role in the conservative movement in the 1980s during the Presi ...

, the Free Congress Foundation, and the National Right to Work Committee

The National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, established in 1968, is a nonprofit organization that seeks to advance right-to-work laws in the United States.

History

National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation (NRTW) was founded in ...

.

Boycott begins

Hispanic and African American groups

Starting in 1966, the Colorado chapter of theHispanic

The term Hispanic () are people, Spanish culture, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or broadly. In some contexts, Hispanic and Latino Americans, especially within the United States, "Hispanic" is used as an Ethnici ...

veterans' organization

A veterans' organization, also known as an , is an organization composed of persons who served in a country's Military, armed forces, especially those who served in the armed forces during a period of war. The organization's concerns include Vete ...

American GI Forum

The American GI Forum (AGIF) is a congressionally chartered Hispanic veterans and civil rights organization founded in 1948. Its motto is "Education is Our Freedom and Freedom should be Everybody's Business". AGIF operates chapters throughout ...

, along with the Denver

Denver ( ) is a List of municipalities in Colorado#Consolidated city and county, consolidated city and county, the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Colorado, most populous city of the U.S. state of ...

-based group Crusade for Justice, initiated a boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent resistance, nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organisation, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for Morality, moral, society, social, politics, political, or Environmenta ...

against Coors due to the company's discrimination against Mexican Americans

Mexican Americans are Americans of full or partial Mexican descent. In 2022, Mexican Americans comprised 11.2% of the US population and 58.9% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexican Americans were born in the United State ...

. Specifically, they cited the fact that Hispanic workers constituted only a small fraction of the total employees at Coors, with only 27 of the 1,330 employees in 1968 being Mexican Americans (approximately 2 percent of Coors' total workforce, compared to 15-20% of the population statewide). Additionally, many of the jobs held by Hispanic employees at Coors were menial labor positions. Women also constituted a very small portion of Coors' workforce, with only 56 women (44 of whom were white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

) working for the company in 1967. In August 1970, the Colorado Civil Rights Commission found the company guilty of firing a worker due to his race. The commission ultimately ruled against the company on two separate occasions in the early 1970s for discriminating against African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

workers. A September 1975 complaint filed by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is a federal agency that was established via the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to administer and enforce civil rights laws against workplace discrimination. The EEOC investigates discrimination ...

(EEOC) alleged that almost all of the African Americans and Mexican Americans at Coors worked in unskilled or semiskilled positions and that almost all of the women were employed in either office or service positions, or as clerical worker

Clerical may refer to:

* Pertaining to the clergy

* Pertaining to a clerical worker

* Clerical script, a style of Chinese calligraphy

* Clerical People's Party

See also

* Cleric (disambiguation)

* Clerk (disambiguation)

{{disambiguat ...

s. That month, the EEOC filed a lawsuit

A lawsuit is a proceeding by one or more parties (the plaintiff or claimant) against one or more parties (the defendant) in a civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today ...

against the company with the United States District Court for the District of Colorado

The United States District Court for the District of Colorado (in case citations, D. Colo. or D. Col.) is a federal court in the Tenth Circuit (except for patent claims and claims against the U.S. government under the Tucker Act, which are a ...

, with the company settling out of court in 1977.

In addition to employment discrimination, Hispanic activists also singled out Joseph Coors' actions while university regent and the Coors family's response to the Delano grape strike

The Delano grape strike was a labor strike organized by the United Farm Workers, Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), a predominantly Filipino and AFL-CIO-sponsored labor organization, against table grape growers in Delano, Californ ...

. During the strike and associated boycott, which had been organized by the United Farm Workers

The United Farm Workers of America, or more commonly just United Farm Workers (UFW), is a labor union for farmworkers in the United States. It originated from the merger of two workers' rights organizations, the National Farm Workers Associatio ...

, the Coors family supported non-union grape growers, and the Crusade for Justice's newspaper ''El Gallo'' published images reportedly showing Coors trucks being used to transport grapes harvested by non-union farmers to markets. In 1969, 43 students at Southern Colorado State College

Colorado State University Pueblo (CSU Pueblo) is a public university in Pueblo, Colorado, United States. It is part of the Colorado State University System and a Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI).

History 1933 to 1959

The idea for starting ...

protested Coors by blocking people at a local pub from ordering Coors beer. 15 of the students were arrested, and the college later filed a restraining order

A restraining order or protective order is an order used by a court to protect a person in a situation often involving alleged domestic violence, child abuse and neglect, assault, harassment, stalking, or sexual assault.

Restraining and perso ...

against the protestors. The same year, the boycott grew nationwide, with the national chapter of the American GI Forum instituting a boycott against Coors. This action was supported by several other national organizations representing Hispanics and Mexican Americans, including the Mexican American Youth Organization and the Raza Unida Party

Partido Nacional de La Raza Unida (LRUP; National United Peoples PartyArmando Navarro (2000) ''La Raza Unida Party'', p. 20 or United Race Party) was a Hispanic political party centered on Chicano (Mexican-American) nationalism. It was created in ...

. Representatives from the American GI Forum had several meetings with William Coors during this time to address the issues they were protesting, but the discussions proved fruitless.

Polygraph testing and LGBT response

Another point of contention between the company and protestors involved the use of

Another point of contention between the company and protestors involved the use of polygraph

A polygraph, often incorrectly referred to as a lie detector test, is a pseudoscientific device or procedure that measures and records several physiological indicators such as blood pressure, pulse, respiration, and skin conductivity while a ...

tests on job applicants, a process that the company had implemented following the 1960 kidnapping and murder of Adolph Coors III. These tests, conducted during the applicant's background check

A background check is a process used by an organisation or person to verify that an individual is who they claim to be, and check their past record to confirm education, employment history, and other activities, and for a criminal record. The fr ...

, were a significant point of contention among union members at the company, with the union alleging that the questions asked violated privacy and led to discrimination. Questions asked during the testing covered topics including the use of marijuana

Cannabis (), commonly known as marijuana (), weed, pot, and ganja, List of slang names for cannabis, among other names, is a non-chemically uniform psychoactive drug from the ''Cannabis'' plant. Native to Central or South Asia, cannabis has ...

, personal debts the individual owed, political affiliations of the application (specifically regarding "subversive, revolutionary or communist activities"), and a question that read, "Is there anything in your personal life that might tend to discredit or embarrass this company if it were known?" Multiple sources also reported that applicants were asked about their sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring personal pattern of romantic attraction or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. Patterns ar ...

. While critics of the testing alleged that the company used the information collected to prevent people from being hired based on political affiliations or sexuality, the company denied this. According to William Coors, approximately 45 percent of applicants failed the polygraph testing, primarily with regards to questions over drug use.

Despite the company's claims, Coors became known throughout the LGBT community

The LGBTQ community (also known as the LGBT, LGBT+, LGBTQ+, LGBTQIA, LGBTQIA+, or queer community) comprises LGBTQ people, LGBTQ individuals united by LGBTQ culture, a common culture and LGBTQ movements, social movements. These Community, comm ...

for its homophobic

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who identify or are perceived as being lesbian, Gay men, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred, or ant ...

practices, and by 1973, the boycott had expanded to include members of that community. The LGBT community also began to forge an alliance against Coors with local unions, who resented the company's anti-unionism. Around this time, president Allan Baird of Teamsters

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) is a trade union, labor union in the United States and Canada. Formed in 1903 by the merger of the Team Drivers International Union and the Teamsters National Union, the union now represents a di ...

Local 921, which had organized Coors distribution Distribution may refer to:

Mathematics

*Distribution (mathematics), generalized functions used to formulate solutions of partial differential equations

*Probability distribution, the probability of a particular value or value range of a varia ...

workers in San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, worked with activist Howard Wallace (an openly gay truck driver

A truck driver (commonly referred to as a trucker, teamster or driver in the United States and Canada; a truckie in Australia and New Zealand; an HGV driver in the United Kingdom, Ireland and the European Union, a lorry driver, or driver in ...

and Teamsters member) to organize a large-scale boycott in the Bay Area

The San Francisco Bay Area, commonly known as the Bay Area, is a region of California surrounding and including San Francisco Bay, and anchored by the cities of Oakland, San Francisco, and San Jose. The Association of Bay Area Governments ...

, leading to numerous gay bar

A gay bar is a Bar (establishment), drinking establishment that caters to an exclusively or predominantly lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ+) clientele; the term ''gay'' is used as a broadly inclusive concept for LGBTQ+ communi ...

s refusing to carry Coors products. Gay rights activist

A list of notable LGBTQ social movements, LGBTQ rights activists who have worked to advance LGBTQ rights by political change, legal action or publication. Ordered by country, alphabetically.

Albania

* Xheni Karaj, founder of Aleanca LGBT org ...

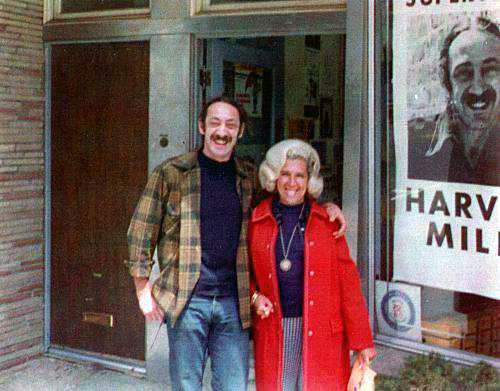

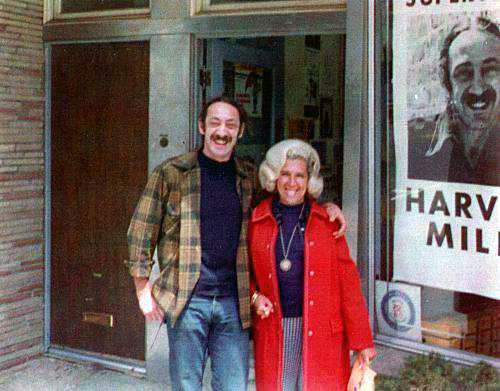

Scott Smith was also involved in the boycott and brought it to the attention of Harvey Milk

Harvey Bernard Milk (May 22, 1930 – November 27, 1978) was an American politician and the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California, as a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.

Milk was born and raised i ...

, a noted gay activist and politician, who met with Baird in 1973 and helped coordinate the boycott, strengthening the alliance between the traditionally conservative Teamsters union and the area's gay community. Through Milk, the boycott spread throughout the Castro District

The Castro District, commonly referred to as the Castro, is a neighborhood in Eureka Valley in San Francisco. The Castro was one of the first gay neighborhoods in the United States. Having transformed from a working-class neighborhood throug ...

, the city's gay neighborhood

A gay village, also known as a gayborhood or gaybourhood, is a geographical area with generally recognized boundaries that is inhabited or frequented by many lesbian, gay, bisexuality, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people. Gay vil ...

. Milk also encouraged the Teamsters to hire openly gay people and to oppose the Briggs Amendment, a California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

ballot measure

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

that would have banned LGBT teachers from employment. Activist Cleve Jones

Cleve Jones (born October 11, 1954) is an American AIDS and LGBT rights activist. He conceived the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, which has become, at 54 tons, the world's largest piece of community folk art as of 2020. In 1983 at the onset ...

was also involved, and he later claimed that the Bay Area boycott was the first-ever instance of collaboration between labor unions and the gay rights movement

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) movements are social movements that advocate for LGBTQ people in society.

Although there is not a primary or an overarching central organization that represents all LGBTQ people and their i ...

. Activist Tami Gold

Tami Kashia Gold is a documentary filmmaker, visual artist and educator. She is also a professor at Hunter College of the City University of New York in the Department of Film and Media Studies.

Biography

As a teenager, Gold studied in Mexico ...

later claimed that the boycott was "perhaps one of the first major public demonstrations of the links between class and sexual identity".

Strike action

During the boycott, brewery workers at Coors had union representation as members of theBrewery Workers

A brewery or brewing company is a business that makes and sells beer. The place at which beer is commercially made is either called a brewery or a beerhouse, where distinct sets of brewing equipment are called plant. The commercial brewing of be ...

Local 366, which had existed at the plant since at least a failed strike in 1957. A 1975 article in ''The New York Times'' described the unions at Coors as weak, highlighting several failed strikes that had occurred throughout the company's history. At the time, union members reported that working conditions were not ideal, with the most significant point of contention being the 21 causes for firing, which included doing anything "which would discourage any person from drinking Coors beer" and "making disparaging remarks about the employer". While the union's president claimed that the labor contract was "pretty lousy", he admitted that the pay and benefits offered by the company were better than most in the industry, and that " long as they're getting a high wage rate and aren't faced with disciplinary action, their contract doesn't mean much to them".

In 1976, under Colorado's Labor Peace Law provisions, Coors demanded a vote amongst brewery workers on whether the brewery would remain a

In 1976, under Colorado's Labor Peace Law provisions, Coors demanded a vote amongst brewery workers on whether the brewery would remain a union shop

In labor law, a union shop, also known as a post-entry closed shop, is a form of a union security clause. Under this, the employer agrees to either only hire labor union members or to require that any new employees who are not already union mem ...

. In a vote held that December, the union shop was kept, with 92 percent voting in favor. On March 1 of the following year, the labor contract between Coors and the local expired, and ensuing negotiations on a new contract were bogged down by disagreements between the two. The disagreements were not related to pay but instead concerned the company's grounds for dismissal and their use of polygraph testing for applicants. Additionally, the company had wanted to change policies regarding seniority rights, which the union opposed. On April 5, 1977, approximately 1,500 union members began a strike action against the company with a mass walkout

In labor disputes, a walkout is a labor strike, the act of employees collectively leaving the workplace and withholding labor as an act of protest.

A walkout can also mean the act of leaving a place of work, school, a meeting, a company, or an ...

. However, the next day, the company sent letters to the striking employees saying that they would hire strikebreaker

A strikebreaker (sometimes pejoratively called a scab, blackleg, bootlicker, blackguard or knobstick) is a person who works despite an ongoing strike. Strikebreakers may be current employees ( union members or not), or new hires to keep the orga ...

s if necessary and that, if the striking worker were replaced, they ran the risk of losing their position within the company. On April 12, the AFL–CIO announced a national boycott of Coors in support of Local 366. Around this time, then-company president Jeff Coors, in speaking to the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' is an American Newspaper#Daily, daily newspaper that began publishing in Los Angeles, California, in 1881. Based in the Greater Los Angeles city of El Segundo, California, El Segundo since 2018, it is the List of new ...

'', stated that agreeing to the union's proposals was like "inviting the Russians in to take over America".

Shortly after the strike's start, Coors began pushing for the union shop rule at the brewery to be revoked, which was strongly opposed by the strikers. According to a company official, Coors "didn't believe non-strikers should be forced to join the union or that people should be forced to pay union dues to support the boycott". Within several weeks from the start of the strike, hundreds of strikebreakers had been hired, and many strikers had returned to work. Soon, the main issues of the strike concerned keeping the union shop rule and pushing for the rehiring of strikers. By early 1978, Coors was seeking a vote on whether to decertify the union, and, after agreeing to pay $254,000 in back pay, the ballot became official. By June, it was reported that a majority of strikers had returned to work, and by the time of the vote in early December, only 500 of the initial 1,500 strikers were still on strike. The Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

reported on December 14 that workers had voted 993 to 408 to decertify Brewery Workers Local 366, bringing an end to the strike.

Continued boycott

In 1979, both the American GI Forum and the California-basedMexican American Political Association

The Mexican American Political Association (MAPA) is an organization based in California that promotes the interests of Mexican-Americans, Mexicans, Hispanic and Latino Americans, Latinos, Chicanos, Hispanics, and Latino economic refugees in the U ...

announced that they were ending their boycott, with the GI Forum stating that there had been "some improvement" from the company. However, despite the decertification vote, the AFL–CIO stated their intent to continue their nationwide boycott. Additionally, in the following years, protestors began targeting the Coors Classic

The Coors International Bicycle Classic (1980–1988) was a stage race sponsored by the Coors Brewing Company. Coors was the race's second sponsor; the first, Celestial Seasonings, named the race after its premium tea Red Zinger, which began in ...

, a Colorado-based road bicycle race

Road bicycle racing is the cycle sport discipline of road cycling, held primarily on paved roads. Road racing is the most popular professional form of bicycle racing, in terms of numbers of competitors, events and spectators. The two most com ...

sponsored by Coors. Around 1984, the National Education Association

The National Education Association (NEA) is the largest labor union in the United States. It represents public school teachers and other support personnel, faculty and staffers at colleges and universities, retired educators, and college st ...

(a non-AFL–CIO union with approximately 2 million members at the time, making it the largest labor union in the United States) voted to support the boycott. That same year, the National Organization for Women

The National Organization for Women (NOW) is an American feminist organization. Founded in 1966, it is legally a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization. The organization consists of 550 chapters in all 50 U.S. states and in Washington, D.C. It ...

also launched a boycott due in part to Joseph Coors' opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was a proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States, United States Constitution that would explicitly prohibit sex discrimination. It is not currently a part of the Constitution, though its Ratifi ...

, and with Coors' expansion into Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

, students at the University of Massachusetts Amherst

The University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass Amherst) is a public land-grant research university in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States. It is the flagship campus of the University of Massachusetts system and was founded in 1863 as the ...

voted to ban the beer from the college. Around this time, however, Coors began reaching out to groups that had threatened to boycott. In October 1987, the company signed a $325 million agreement with a coalition consisting of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

and Operation PUSH

Rainbow/PUSH is a Chicago-based nonprofit organization formed as a merger of two nonprofit organizations founded by Jesse Jackson; Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) and the National Rainbow Coalition. The organizations pursue socia ...

, two African American activist organizations. An additional $300 million agreement was made with the Hispanic group La Raza

In Mexico, the Spanish expression ('the people'; literally: 'the race') has historically been used to refer to the mixed-race populations (primarily though not always exclusively in the Western Hemisphere), considered as an ethnic or racia ...

, with the company agreeing to do more business with minority businesses and contractors and hire more minority workers, among other things. As a result of the agreements, the NAACP ended their threats to boycott Coors. The agreements also helped the company's relationship with groups including the National Urban League

The National Urban League (NUL), formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan historic civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of economic and social justice for Afri ...

and the League of United Latin American Citizens

The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) is the largest and oldest Hispanic and Latin-American civil rights organization in the United States. It was established on February 17, 1929, in Corpus Christi, Texas, largely by Hispanic and ...

.

In 1986, the South Dakota Farmers Union announced they would also be boycotting Coors following advertisements Coors released that the union said cast aspersions on local

In 1986, the South Dakota Farmers Union announced they would also be boycotting Coors following advertisements Coors released that the union said cast aspersions on local barley

Barley (), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikele ...

farmers. That same year, Coors announced they would be ending their use of polygraph testing, which had been one of the main issues between the company and union. The replacement screening process would involve a partnership with the firm Equifax

Equifax Inc. is an American multinational consumer credit reporting agency headquartered in Atlanta, Atlanta, Georgia and is one of the three largest consumer credit reporting agency, consumer credit reporting agencies, along with Experian and T ...

, with a company representative stating that the screening process would still allow the company to find if applicants were communists

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, d ...

or on narcotic

The term narcotic (, from ancient Greek ναρκῶ ''narkō'', "I make numb") originally referred medically to any psychoactive compound with numbing or paralyzing properties. In the United States, it has since become associated with opiates ...

s. By 1987, Coors had expanded its market to include 47 states, and it was the only brewery among the top 15 in the nation that was not unionized. In February of that year, during a speech given by William Coors at the Harvard Science Center

The Harvard University Science Center is Harvard University's main classroom and laboratory building for undergraduate science and mathematics, in addition to housing numerous other facilities and services.

Located just north of Harvard Yard, the ...

in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. It is a suburb in the Greater Boston metropolitan area, located directly across the Charles River from Boston. The city's population as of the 2020 United States census, ...

, approximately 200 Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

students picketed the executive and his company. That same month, Coors expanded their market to include New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

and New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

, with the AFL–CIO organizing a regional boycott. However, at the time, the non-AFL–CIO affiliated Teamsters were not part of the boycott, instead focusing on organizing the workers at a Coors brewery in Elkton, Virginia

Elkton (formerly Conrad's Store) is an incorporated town in Rockingham County, Virginia, Rockingham County, Virginia, United States. It is included in the Harrisonburg, Virginia, Harrisonburg Harrisonburg metropolitan area, Metropolitan Statistic ...

. In March, a scuffle broke out at the New York State Capitol

The New York State Capitol, the seat of the Government of New York State, New York state government, is located in Albany, New York, Albany, the List of U.S. state capitals, capital city of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. The seat ...

in Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is located on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River. Albany is the oldes ...

between union members and Coors wholesalers during an event held by company representatives who were publicizing Coors' expansion into the state.

End of the boycott

Agreement between the AFL–CIO and Coors

In 1985, Pete Coors took over the company's day-to-day operations from his father Joseph and immediately began negotiating with the AFL–CIO on an agreement that would end the boycott. The AFL–CIO rejected Coors' initial offer in February 1987, but on August 19, they announced that they had come to an agreement with the company and would end their boycott. Among the concessions, the company agreed to use union workers in the construction of their new facility inVirginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

. This had been a point of contention that prevented the February agreement from being approved. Additionally, the AFL–CIO and the company claimed that the agreement would make it easier for worker organization efforts at Coors facilities, However, any union vote would be overseen by a third party such as the American Arbitration Association

The American Arbitration Association (AAA) is an organization focused in the field of alternative dispute resolution, one of several arbitration organizations that administers arbitration proceedings. Structured as a non-profit, the AAA also admin ...

rather than the National Labor Relations Board

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States that enforces United States labor law, U.S. labor law in relation to collect ...

(NLRB). Shortly after the agreement, the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers

The International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAM) is an AFL–CIO/ CLC trade union representing over 600,000 workers as of 2024 in more than 200 industries with most of its membership in the United States and Canada.

Orig ...

(IAM) announced their intent to start organizing drives at both the Elkton and Golden facilities, while the International Union of Operating Engineers

The International Union of Operating Engineers (IUOE) is a trade union within the United States–based AFL–CIO representing primarily construction workers who work as heavy equipment operators, mechanics, surveyors, and stationary engineers ( ...

(IUOE) and the United Auto Workers

The United Auto Workers (UAW), fully named International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, is an American labor union that represents workers in the United States (including Puerto Rico) and sou ...

(UAW) also expressed interest in organizing Coors workers. An AFL–CIO representative at the time of the announcement claimed that it was "arguably the biggest victory in my time at the federation, and that covers 18 years", while AFL–CIO president Lane Kirkland

Joseph Lane Kirkland (March 12, 1922 – August 14, 1999) was an American labor union leader who served as President of the AFL–CIO from 1979 to 1995.

Life and career

Kirkland was born in Camden, South Carolina, the son of Louise Beardsley (Ri ...

called the boycott "a complete success, a resounding success" and commented on the "more positive approach taken by (the new) management" at Coors. However, some union members criticized the agreement, as Coors did not guarantee a union contract. At the time, union membership in the United States had been on the decline, with activist and writer Jonathan Tasini stating, "Organized labor has been in such desperate straits that the Coors settlement has been perceived as a victory – even though the workers at Coors are still without a union."

Teamsters union drive

At the time of the agreement, the Teamsters were attempting to organize workers at the Golden facility. The ''Los Angeles Times'' reported that the AFL–CIO saw this as a threat to possible union efforts by the IAM, IUOE, and UAW. As part of the agreement, only AFL–CIO unions would be guaranteed an expedited vote on union representation. Following the agreement, the Teamsters continued their efforts to organize at the Golden plant. In late 1987, the Teamsters became an AFL–CIO affiliate. Following this, the Teamsters were the AFL–CIO union tasked with the organization at the Golden plant. In September 1988, it was reported that the Teamsters and Coors disagreed on whether a union vote would include only brewery workers (favored by the Teamsters), or an additional 2,000 container workers who were less favorable to unions (favored by Coors). The dispute was at the time being settled by the NLRB. Ultimately, only the brewery workers participated in the union vote. On December 15, 1988, workers at the Golden plant voted against unionizing with the Teamsters. The vote came after 18 months of campaigning, with the final vote being 1,081 against to 413 in favor of unionizing. Among the issues presented during the campaign, the Teamsters cited increased wages and pension plans with Teamsters members at Anheuser-Busch as examples of what could happen with a union at Coors. However, Coors rebutted that Anheuser-Busch was larger than Coors and could therefore afford the larger pay and benefits.Impact

The strike and boycotts had a considerable impact on Coors, with Jonathan Tasini stating that they "effectively helped stunt the company's growth". In the late 1970s, the company'smarket share

Market share is the percentage of the total revenue or sales in a Market (economics), market that a company's business makes up. For example, if there are 50,000 units sold per year in a given industry, a company whose sales were 5,000 of those ...

in California had dropped from a high of over 40 percent to just 14 percent. In the company's home state of Colorado, there was a similar drop from 47 percent in 1977 to 24 percent in 1984. In 1987, the ''Los Angeles Times'' claimed that "Coors officers have conceded that the boycott, which was joined over the years by various special-interest groups opposed to the outspoken political conservatism of Coors family patriarch Joseph Coors, had damaged its main market areas in the West and its drive for nationwide sales". However, these numbers and the impact the boycott had on the decline are disputed by Coors representatives. A company representative in 1983 claimed that, while the boycott hurt sales in California, the overall decline in sales during this time was due to increased competition from the Miller Brewing Company

The Miller Brewing Company is an American brewery and beer company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. It was founded in 1855 by Frederick Miller. Molson Coors acquired the full global brand portfolio of Miller Brewing Company in 2016, and operates the ...

and Anheuser-Busch. Speaking later about the boycott, Pete Coors stated that "the '70s and early '80s were not a stellar time for the company". The decrease in market share in Coors' limited market area may have contributed to the company's decision to expand nationwide, with the company having a presence in every state except Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

by 1988. This is compared to the company's stance in 1975 when a company representative claimed there were no plans at the time to expand to the eastern United States.

Legacy in the LGBT community

In the years after the boycott ended, the relationship between Coors and the LGBT community remained frayed. In a 1998 article from thealternative newspaper

An alternative newspaper is a type of newspaper that eschews comprehensive coverage of general news in favor of stylized reporting, opinionated reviews and columns, investigations into edgy topics and magazine-style feature stories highlighting ...

''The Village Voice

''The Village Voice'' is an American news and culture publication based in Greenwich Village, New York City, known for being the country's first Alternative newspaper, alternative newsweekly. Founded in 1955 by Dan Wolf (publisher), Dan Wolf, ...

'', the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation

GLAAD () is an American non-governmental media monitoring organization. Originally founded as a protest against defamatory coverage of gay and lesbian demographics and their portrayals in the media and entertainment industries, it has since ex ...

was criticized for accepting a $110,000 donation from Coors, stating that, at the time, the boycott was still active in the LGBT community. At the time, Coors was trying to make inroads into the LGBT community by increasing advertisements targeting the community (several of which highlighted the fact that the company offered domestic partnership benefits

A domestic partnership is an intimate relationship between people, usually couples, who live together and share a common domestic life but who are not married (to each other or to anyone else). People in domestic partnerships receive legal ben ...

to workers) and donating to events such as pride parade

A pride parade (also known as pride event, pride festival, pride march, or pride protest) is an event celebrating lesbian, Gay men, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) social and self-acceptance, achievements, LGBT rights by country o ...

s. However, individuals within the community criticized the company's past and the Coors family's continued support for right-wing politics. As a representative for ACT UP

AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) is an international, grassroots political group working to end the AIDS pandemic. The group works to improve the lives of people with AIDS through direct action, medical research, treatment and advocacy, ...

stated in that ''Village Voice'' article, "The change in employee practices is important. But meanwhile they're still trying to kill us. For anyone in the gay community to do business with Coors is suicidal." In 2002, the LGBT newspaper '' Out Front Colorado'' was criticized for refusing to run an ad submitted by the LGBT committee of the National Lawyers Guild

The National Lawyers Guild (NLG) is a progressive public interest association of lawyers, law students, paralegals, jailhouse lawyers, law collective members, and other activist legal workers, in the United States. The group was founded in 193 ...

that criticized Coors and contended that the boycott was still active. In 2019, union and LGBT activist Nancy Wohlforth commented that "to this day, you can't find Coors in a gay bar in San Francisco", a claim backed up by a 2017 article by the Teamsters on the impact of the boycott. A 2014 article published by Colorado Public Radio

Colorado Public Radio (CPR) is a public radio state network based in Denver, Colorado that broadcasts three services: news, classical music and Indie 102.3, which plays adult album alternative music. CPR airs its programming on 15 full-power ...

stated that "grudges against Coors continue" among groups that had been involved in the boycotts.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * {{Cite book, last=Weir, first=Robert E., url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PnJ7PmAyi_MC, title=Workers in America: A Historical Encyclopedia, publisher= ABC-Clio, year=2013, isbn=978-1-59884-719-2, volume=1: A-L, pages=83–87, chapter=Brewery Workers 1966 protests 1970s in LGBTQ history 1970s strikes in the United States 1977 in Colorado 1977 labor disputes and strikes 1978 in Colorado 1978 labor disputes and strikes History of the AFL-CIO African-American history of Colorado Alcohol in the United States Anti-Mexican sentiment in the United States Beer in Colorado Boycotts of organizations Brewery workers Chicano Consumer boycotts Coors family Harvey Milk Hispanic and Latino American history Hispanic and Latino American working class Labor disputes led by the International Brotherhood of Teamsters Labor disputes in Colorado LGBTQ civil rights demonstrations in the United States History of Mexican Americans Molson Coors Beverage Company National Education Association National Organization for Women Post–civil rights era in African-American history