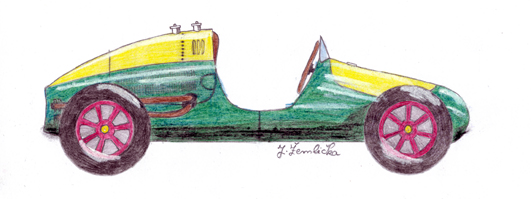

Cooper Mark IV on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cooper Mark IV was a

The Cooper Mark IV was a

The Cooper T12 was a

The Cooper T12 was a

racing-database.com statistics

Racing Database

*http://www.loosefillings.com {{F1 cars 1950 1950 Formula One season cars Cooper Formula One cars Cooper racing cars Formula Two cars Formula Three cars

Formula Three

Formula Three, also called Formula 3, abbreviated as F3, is a third-tier class of open-wheel formula racing. The various championships held in Europe, Australia, South America and Asia form an important step for many prospective Formula One dr ...

and Formula Two

Formula Two (F2 or Formula 2) is a type of open-wheel formula racing category first codified in 1948. It was replaced in 1985 by Formula 3000, but revived by the FIA from 2009–2012 in the form of the FIA Formula Two Championship. The name r ...

racing car designed and built by the Cooper Car Company

The Cooper Car Company is a British car manufacturer founded in December 1947 by Charles Cooper and his son John Cooper. Together with John's boyhood friend, Eric Brandon, they began by building racing cars in Charles's small gara ...

at Surbiton

Surbiton is a suburban neighbourhood in South West London, within the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames (RBK). It is next to the River Thames, southwest of Charing Cross. Surbiton was in the historic county of Surrey and since 1965 it h ...

, Surrey, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, in 1950.

Following the adoption of the 500cc formula for F3 in 1949, Cooper evolved the Mark III to use a JA Prestwich Industries

JA Prestwich Industries, was a British engineering equipment manufacturing company named after founder John Alfred Prestwich, which was formed in 1951 by the amalgamation of J.A.Prestwich and Company Limited and Pencils Ltd.

History

John Prest ...

(JAP) single.

The ladder frame was retained, with the aluminum body supported by hoops. Lockheed twin-shoe disc brakes became standard, coupled to two master cylinder

In automotive engineering, the master cylinder is a control device that converts force (commonly from a driver's foot) into hydraulic pressure. This device controls slave cylinders located at the other end of the hydraulic brake system.

As pi ...

s. The suspension was Fiat 500

The Fiat 500 ( it, Cinquecento, ) is a rear-engined, four-seat, small city car that was manufactured and marketed by Fiat Automobiles from 1957 until 1975 over a single generation in two-door saloon and two-door station wagon bodystyles.

La ...

transverse leaf spring

A leaf spring is a simple form of spring commonly used for the suspension in wheeled vehicles. Originally called a ''laminated'' or ''carriage spring'', and sometimes referred to as a semi-elliptical spring, elliptical spring, or cart spring, ...

independent suspension

Independent suspension is any automobile suspension system that allows each wheel on the same axle to move vertically (i.e. reacting to a bump on the road) independently of the others. This is contrasted with a beam axle or deDion axle system i ...

, used at front and rear.Kettlewell, p.429.

History

The Mark IV came in a standard version (T11) for F3, and long-wheelbase (T12) variant for F2. Standard for the T11 was a one-cylinder Speedway JAP engine. The T12 was powered by a 1000cc engine. The first 500 modified with a 1000cc JAP twin was prepared by customerSpike Rhiando

Spike, spikes, or spiking may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Books

* ''The Spike'' (novel), a novel by Arnaud de Borchgrave

* ''The Spike'' (book), a nonfiction book by Damien Broderick

* ''The Spike'', a starship in Peter F. Hamilto ...

in 1948. In 1949, a model powered by the engine from an MG TD was built, and won on its first outing. Cliff Davis

In geography and geology, a cliff is an area of rock which has a general angle defined by the vertical, or nearly vertical. Cliffs are formed by the processes of weathering and erosion, with the effect of gravity. Cliffs are common on ...

was the most successful driver to campaign one.

Cars were supplied without engines, which the customer provided. (This would become routine in Formula One

Formula One (also known as Formula 1 or F1) is the highest class of international racing for open-wheel single-seater formula racing cars sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). The World Drivers' Championship ...

in later years.) The T12s were best-suited for hillclimbs and sprints, not being durable enough for longer events.

The F2 Mark IV, based on the TD-engined variant, appeared in 1952. It was powered by a Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city i ...

inline six

The straight-six engine (also referred to as an inline-six engine; abbreviated I6 or L6) is a piston engine with six cylinders arranged in a straight line along the crankshaft. A straight-six engine has perfect primary and secondary engine bala ...

, giving up to the Ferraris. At just , they had on the Ferraris, and better cornering, due to their mid-mounted engines. It made its debut in at Goodwood on Easter Monday

Easter Monday refers to the day after Easter Sunday in either the Eastern or Western Christian traditions. It is a public holiday in some countries. It is the second day of Eastertide. In Western Christianity, it marks the second day of the ...

, run by Eric Brandon

Eric Brandon (18 July 1920 in East Ham, Essex – 8 August 1982 in Gosport, Hampshire) was a motor racing driver and businessman. He was closely associated with the Cooper Car Company, and was instrumental in the early development of the company. ...

and Alan Brown (for ''Ecurie Richmond

Ecurie may refer to:

* Écurie, a commune in the Pas-de-Calais département in France

* Several car racing teams (compare '' scuderias'') :

** Ecurie Belge

** Ecurie Bleue

** Ecurie Bonnier

** Ecurie Ecosse, a former motor racing team from Scot ...

'') and Mike Hawthorn

John Michael Hawthorn (10 April 1929 – 22 January 1959) was a British racing driver. He became the United Kingdom's first Formula One World Champion driver in 1958, whereupon he announced his retirement, having been profoundly affected by the ...

(driving for Bob Chase). Hawthorn took the Formula Two event and one of the two Formula Libre

Formula Libre, also known as Formule Libre, is a form of automobile racing allowing a wide variety of types, ages and makes of purpose-built racing cars to compete "head to head". This can make for some interesting matchups, and provides the oppo ...

races, and came second behind González

Gonzalez or González may refer to:

People

* González (surname)

Places

* González, Cesar, Colombia

* González Municipality, Tamaulipas, Mexico

* Gonzalez, Florida, United States

* González Island, Antarctica

* González Anchorage, Antarctica ...

' 4½ l Ferrari in another ''Libre'' outing. It marked the first mid-engined entrant in Formula Two, and only the second marque

A brand is a name, term, design, symbol or any other feature that distinguishes one seller's good or service from those of other sellers. Brands are used in business, marketing, and advertising for recognition and, importantly, to create a ...

in top-rank European racing, following Auto Union

Auto Union AG, was an amalgamation of four German automobile manufacturers, founded in 1932 and established in 1936 in Chemnitz, Saxony. It is the immediate predecessor of Audi as it is known today.

As well as acting as an umbrella firm ...

.

Mark IVs competed successfully in F2 throughout 1952 and 1953,Kettlewell, p.430. driven by Hawthorn, Peter Collins, and of course John Cooper himself, among others. (Stirling Moss

Sir Stirling Craufurd Moss (17 September 1929 – 12 April 2020) was a British Formula One racing driver. An inductee into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame, he won 212 of the 529 races he entered across several categories of com ...

' unsuccessful Cooper-Alta was actually built by a different John Cooper, '' Autocar''s sport editor.) In September 1950, Raymond Sommer

Raymond Sommer (31 August 1906 – 10 September 1950) was a French motor racing driver. He raced both before and after WWII with some success, particularly in endurance racing. He won the 24 Hours of Le Mans endurance race in both and , and altho ...

died in a wreck at Cadours in a T12. It sold used at £425 in 1952.

Arthur Owen modified a Mark IV with a streamlined glassfibre

Fiberglass (American English) or fibreglass (Commonwealth English) is a common type of fiber-reinforced plastic using glass fiber. The fibers may be randomly arranged, flattened into a sheet called a chopped strand mat, or woven into glass cloth ...

body and 250cc Norton engine late in 1957. Bill Knight used this car to set five speed records at Monza

Monza (, ; lmo, label= Lombard, Monça, locally ; lat, Modoetia) is a city and ''comune'' on the River Lambro, a tributary of the Po in the Lombardy region of Italy, about north-northeast of Milan. It is the capital of the Province of M ...

.

Cooper T12

The Cooper T12 was a

The Cooper T12 was a Formula Two

Formula Two (F2 or Formula 2) is a type of open-wheel formula racing category first codified in 1948. It was replaced in 1985 by Formula 3000, but revived by the FIA from 2009–2012 in the form of the FIA Formula Two Championship. The name r ...

/Formula Three

Formula Three, also called Formula 3, abbreviated as F3, is a third-tier class of open-wheel formula racing. The various championships held in Europe, Australia, South America and Asia form an important step for many prospective Formula One dr ...

racing car produced by the Cooper Car Company

The Cooper Car Company is a British car manufacturer founded in December 1947 by Charles Cooper and his son John Cooper. Together with John's boyhood friend, Eric Brandon, they began by building racing cars in Charles's small gara ...

.

The car was developed as the long chassis version of the Cooper Mk IV design, making it eligible to use in both F3 (with JAP 0.5 L engines) and F2 (with JAP 1.0/1.1 L engines).

In it made a single outing in a Formula One World Championship race, entered by Horschell Racing Corporation for Harry Schell

Henry O'Reilly "Harry" Schell (June 29, 1921 – May 13, 1960) was an American Grand Prix motor racing driver. He was the first American driver to start a Formula One Grand Prix.

Early life

Schell was born in Paris, France, the son of expatri ...

at the Monaco Grand Prix

The Monaco Grand Prix (french: Grand Prix de Monaco) is a Formula One motor racing event held annually on the Circuit de Monaco, in late May or early June. Run since 1929, it is widely considered to be one of the most important and prestigiou ...

, where he retired. It was also used by various privateers. Altogether it was used at 35 races, achieving two podium positions. Its only win was achieved by John Barber John Barber may refer to:

Politics

*John Barber (Lord Mayor of London) (died 1741), Jacobite printer, Lord Mayor of London in 1732

*John Barber, represented Tryon County in the North Carolina General Assembly of 1777

* John Roaf Barber (1841–1917 ...

at the 500 Car Club Formula 2 Race.

Complete Formula One World Championship results

( key) (results in bold indicate pole position, results in ''italics'' indicate fastest lap)Notes

Sources

*Kettlewell, Mike. "Cooper: Forerunner of the Modern Racing Car", in Northey, Tom, editor. ''World of Automobiles'', Volume 4, pp. 427–433. London: Phoebus, 1974.racing-database.com statistics

External links

Racing Database

*http://www.loosefillings.com {{F1 cars 1950 1950 Formula One season cars Cooper Formula One cars Cooper racing cars Formula Two cars Formula Three cars