Individual contributors to

classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited governmen ...

and political

liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

are associated with philosophers of the

Enlightenment. Liberalism as a specifically named ideology begins in the late 18th century as a movement towards self-government and away from

aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

. It included the ideas of

self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

, the primacy of the individual and the nation as opposed to the state and religion as being the fundamental units of law, politics and economy.

Since then liberalism broadened to include a wide range of approaches from Americans

Ronald Dworkin

Ronald Myles Dworkin (; December 11, 1931 – February 14, 2013) was an American legal philosopher, jurist, and scholar of United States constitutional law. At the time of his death, he was Frank Henry Sommer Professor of Law and Philosophy at ...

,

Richard Rorty

Richard McKay Rorty (October 4, 1931 – June 8, 2007) was an American philosopher, historian of ideas, and public intellectual. Educated at the University of Chicago and Yale University, Rorty's academic career included appointments as the Stu ...

,

John Rawls

John Bordley Rawls (; February 21, 1921 – November 24, 2002) was an American moral philosophy, moral, legal philosophy, legal and Political philosophy, political philosopher in the Modern liberalism in the United States, modern liberal tradit ...

and

Francis Fukuyama

Francis Yoshihiro Fukuyama (; born October 27, 1952) is an American political scientist, political economist, and international relations scholar, best known for his book '' The End of History and the Last Man'' (1992). In this work he argues th ...

as well as the Indian

Amartya Sen

Amartya Kumar Sen (; born 3 November 1933) is an Indian economist and philosopher. Sen has taught and worked in England and the United States since 1972. In 1998, Sen received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions ...

and the Peruvian

Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1497 – 21 May 1542) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru, ...

. Some of these people moved away from

liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

while others espoused other

ideologies

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

before turning to liberalism. There are many different views of what constitutes liberalism, and some liberals would feel that some of the people on this list were not true liberals. It is intended to be suggestive rather than exhaustive. Theorists whose ideas were mainly typical for one country should be listed in that country's section of

liberalism worldwide. Generally only thinkers are listed whereas politicians are only listed when they also made substantial contributions to liberal theory beside their active political work.

Classical contributors to liberalism

Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

(Athens, 384–322 BC) is revered among political theorists for his seminal work ''

Politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

''. He made invaluable contributions to liberal theory through his observations on different forms of government and the nature of man.

He begins with the idea that the best government provides an active and "

happy

Happiness is a complex and multifaceted emotion that encompasses a range of positive feelings, from contentment to intense joy. It is often associated with positive life experiences, such as achieving goals, spending time with loved ones, ...

" life for its people. Aristotle then considers six forms of government:

Monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

,

Aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

, and

Polity

A polity is a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of political Institutionalisation, institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources.

A polity can be any group of people org ...

on one side as 'good' forms of government, and

Tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English language, English usage of the word, is an autocracy, absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurper, usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defen ...

,

Oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

, and

Democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

as 'bad' forms. Considering each in turn, Aristotle rejects Monarchy as infantilizing of citizens, Oligarchy as too profit-motivated, Tyranny as against the will of the people, Democracy as serving only to the poor, and Aristocracy (known today as

Meritocracy

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods or political power are vested in individual people based on ability and talent, rather than ...

) as ideal but ultimately impossible. Aristotle finally concludes that a polity—a combination between democracy and oligarchy, where most can vote but must choose among the rich and

virtuous

A virtue () is a trait of excellence, including traits that may be moral, social, or intellectual. The cultivation and refinement of virtue is held to be the "good of humanity" and thus is valued as an end purpose of life or a foundational pri ...

for governors—is the best compromise between

idealism

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical realism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysics, metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, Spirit (vital essence), spirit, or ...

and

realism.

In addition, Aristotle was a firm supporter of

private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental Capacity (law), legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which is owned by a state entity, and from Collective ownership ...

. He refuted Plato's argument for a

collectivist

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and groups. Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership, struct ...

society in which family and property are held in common: Aristotle makes the argument that when one's own son or land is rightfully one's own, one puts much more effort into cultivating that item, to the ultimate betterment of society. He references

barbarian

A barbarian is a person or tribe of people that is perceived to be primitive, savage and warlike. Many cultures have referred to other cultures as barbarians, sometimes out of misunderstanding and sometimes out of prejudice.

A "barbarian" may ...

tribes of his time in which property was held in common, and the laziest of the bunch would always take away large amounts of food grown by the most diligent.

Cicero

His Stoic, Cato, advocated for Greek Stoicism in Cicero's books. It's a development of Aristotle's ethics and goes further, advocating equal rights for all people. It was found to be scientifically true on inspection in the '90s, by Becker (1998). He was also a major influence to John Locke.

Laozi

Laozi

Laozi (), also romanized as Lao Tzu #Name, among other ways, was a semi-legendary Chinese philosophy, Chinese philosopher and author of the ''Tao Te Ching'' (''Laozi''), one of the foundational texts of Taoism alongside the ''Zhuangzi (book) ...

was a Chinese philosopher and writer, considered the founder of

Taoism

Taoism or Daoism (, ) is a diverse philosophical and religious tradition indigenous to China, emphasizing harmony with the Tao ( zh, p=dào, w=tao4). With a range of meaning in Chinese philosophy, translations of Tao include 'way', 'road', ' ...

. Arguing that Laozi is a

libertarian

Libertarianism (from ; or from ) is a political philosophy that holds freedom, personal sovereignty, and liberty as primary values. Many libertarians believe that the concept of freedom is in accord with the Non-Aggression Principle, according ...

, James A. Dorn wrote that Laozi, like many 18th-century liberals, "argued that minimizing the role of government and letting individuals

develop spontaneously would best achieve social and economic harmony."

Liberal thinkers of the Muslim Golden Age

The

Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of scientific, economic, and cultural flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century.

This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign o ...

(8th to 14th century) was marked by a flourishing of intellectual activity in the Islamic world. Several scholars and thinkers from this era contributed to ideas that align with certain liberal principles, emphasizing reason, justice, and individual rights.

Al-Farabi

file:A21-133 grande.webp, thumbnail, 200px, Postage stamp of the USSR, issued on the 1100th anniversary of the birth of Al-Farabi (1975)

Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (; – 14 December 950–12 January 951), known in the Greek East and Latin West ...

(872–950)

Al-Farabi, known as "the Second Teacher," was a philosopher influential in transmitting Greek philosophy to the Islamic world. His political philosophy, seen in works like

The Virtuous City, stressed the importance of justice and the common good in governance, influencing both Muslim and European thought.

Averroes

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinization of names, Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and Faqīh, jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astron ...

(1126–1198)

Ibn Rushd, a Spanish-Arab philosopher, advocated for the compatibility of reason and philosophy with Islamic faith. His commentaries on Aristotle and independent works promoted the separation of reason and revelation, profoundly influencing both Islamic and Western thought.

Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

(980–1037)

Ibn Sina, a polymath known for contributions to medicine and metaphysics, delved into political philosophy. In *The Book of Healing*, he discussed the need for a well-ordered state, emphasizing the role of a philosopher-king guided by reason and wisdom.

Ibn Tufayl

Ibn Ṭufayl ( – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theologian, physician, astronomer, and vizier.

As a philosopher and novelist, he is most famous for writing the first philosophical no ...

(1105–1185)

Ibn Tufail, a philosopher and physician, explored individualism and reason in

Hayy ibn Yaqdhan. The novel discussed a person raised in isolation, emphasizing themes of individual pursuit of knowledge.

From Machiavelli to Spinoza

Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise '' The Prince'' (), writte ...

(Florence, 1469–1527), best known for his ''Il Principe'' was the founder of realist political philosophy, advocated

republican government, citizen armies, protection of personal property, and restraint of government expenditure as being necessary to the liberties of a republic. He wrote extensively on the need for individual initiative—''virtu''—as an essential characteristic of stable government. He argued that liberty was the central good which government should protect, and that "good people" would make good laws, whereas people who had lost their virtue could maintain their liberties only with difficulty. His Discourses on Livy outlined realism as the central idea of political study and favored "Republics" over "Principalities".

Machiavelli differed from true liberal thinking however, in that he still noted the benefits of princely governance. He states that republican leaders need to "act alone" if they want to reform a republic, and offers the example of Romulus, who killed his brother and co-ruler to found a great city. Republics need to refer to arbitrary and violent measures if it is necessary to maintain the structure of the government, as Machiavelli says that they have to ignore thoughts of justice and fairness.

Anti-statist liberals consider Machiavelli's distrust as his main message, noting his call for a strong state under a strong leader, who should use any means to establish his position, whereas liberalism is an ideology of

individual freedom

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and ad ...

and voluntary choices.

* Contributing literature:

** ''

Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio'', 1512–1517 (Discourse on the First Decade of Titus Livius)

Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

(Netherlands, 1466–1536) was an advocate of

humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

, critic of entrenched interests, irrationality and superstition. Erasmusian societies formed across Europe, to some extent in response to the turbulence of the

Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

.

In his ''

De libero arbitrio diatribe sive collatio

' (literally ''Of free will: Discourses or Comparisons'') is the Latin title of a polemical work written by Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam in 1524. It is commonly called ''The Freedom of the Will'' or ''On Free Will'' in English. It was writt ...

'' (1524), he analyzes the Lutheran exaggeration of the obvious limitations on human freedom.

* Contributing literature

** ''Stultitiae Laus'', 1509 (''

The Praise of Folly

''In Praise of Folly'', also translated as ''The Praise of Folly'' ( or ), is an essay written in Latin in 1509 by Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam and first printed in June 1511. Inspired by previous works of the Italian humanist ''De Triumpho ...

)''

** ''De libero arbitrio diatribe sive collatio'', 1524

Étienne de La Boétie

Étienne de La Boétie

Étienne or Estienne de La Boétie (; ; 1 November 1530 – 18 August 1563) was a French magistrate, classicist, writer, poet and political theorist, best remembered for his friendship with essayist Michel de Montaigne. His early political trea ...

(France, 1530–1563) was a French writer, magistrate and political theorist. According to Etienne the chief question of political philosophy was the question of how people come to accept the will of

tyrant

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

s.

* Contributing literature

**

Discourse on Voluntary Servitude, 1577

Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius ( ; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Hugo de Groot () or Huig de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, statesman, poet and playwright. A teenage prodigy, he was born in Delft an ...

(Netherlands 1583–1645)

* Contributing literature

**

Mare Liberum, 1606

** ''

De jure belli ac pacis, 1625''

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

(England, 1588–1679) theorized that government is the result of individual actions and human traits, and that it was motivated primarily by "interest", a term which would become crucial in the development of a liberal theory of government and political economy, since it is the foundation of the idea that individuals can be self-governing and self-regulating. His work ''Leviathan'', did not advocate this viewpoint, but instead that only a strong government could restrain unchecked interest: it did, however, advance a proto-liberal position in arguing for an inalienable "right of nature," the right to defend oneself, even against the state. Though his own ideological position is open to debate, his work influenced Spinoza, Locke, Hamilton, Jefferson, Madison and many other liberals.

* Contributing literature:

** ''

Leviathan

Leviathan ( ; ; ) is a sea serpent demon noted in theology and mythology. It is referenced in several books of the Hebrew Bible, including Psalms, the Book of Job, the Book of Isaiah, and the pseudepigraphical Book of Enoch. Leviathan is of ...

'', 1651 (Theologico-Political Treatise)

Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

(Netherlands, 1632–1677) in his ''

Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

The ''Tractatus Theologico-Politicus'' (''TTP'') or ''Theologico-Political Treatise'', is a 1670 work of philosophy written in Latin by the Dutch philosopher Benedictus Spinoza (1632–1677). The book was one of the most important and contr ...

'' ''(TTP)'' (1670) and ''

Tractatus Politicus'' (1678) defends the importance of

separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

as well as forms of

democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

. In the ''TTP'', Spinoza articulates a strong critique of religious intolerance and a defense of

secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

against the power of religious authorities. Spinoza laid the philosophical groundwork for the emancipation of Jews, putting them on an equal footing as other citizens.

* Contributing literature:

** ''

Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

The ''Tractatus Theologico-Politicus'' (''TTP'') or ''Theologico-Political Treatise'', is a 1670 work of philosophy written in Latin by the Dutch philosopher Benedictus Spinoza (1632–1677). The book was one of the most important and contr ...

'', 1670 (Theologico-Political Treatise)

** ''Tractatus Politicus'', 1677 (Political Treatise)

From Locke to Tocqueville

John Locke

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

's (England, 1632–1704) notion that a "

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

with the

consent of the governed

In political philosophy, consent of the governed is the idea that a government's political legitimacy, legitimacy and natural and legal rights, moral right to use state power is justified and lawful only when consented to by the people or society o ...

" and man's

natural rights

Some philosophers distinguish two types of rights, natural rights and legal rights.

* Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government, and so are ''universal'', ''fundamental rights ...

—

life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

,

liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

, and

estate (

property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, re ...

) as well on

tolerance, as laid down in ''A letter concerning toleration'' and ''Two treatises of government''—had an enormous influence on the development of

liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

. Locke developed a theory of property resting on the actions of individuals, rather than on descent or nobility.

* Some literature:

** ''

A Letter Concerning Toleration'', 1689

** ''

The Second Treatise of Civil Government'', 1689

John Trenchard

John Trenchard (United Kingdom, 1662–1723) was co-author, with Thomas Gordon of ''Cato's Letters''. These newspaper essays condemned

tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English language, English usage of the word, is an autocracy, absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurper, usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defen ...

and advanced principles of

freedom of conscience

Freedom of conscience is the freedom of an individual to act upon their moral beliefs. In particular, it often refers to the freedom to ''not do'' something one is normally obliged, ordered or expected to do. An individual exercising this freedom m ...

and

freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

and were a main vehicle for spreading the

concept

A concept is an abstract idea that serves as a foundation for more concrete principles, thoughts, and beliefs.

Concepts play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied within such disciplines as linguistics, ...

s that had been developed by

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

.

* Some literature:

** ''

Cato's Letters'' / John Trenchard & Thomas Gordon, 1720–1723

Charles de Montesquieu

Charles de Montesquieu

Charles de Montesquieu (France, 1689–1755)

In ''The Spirit of Law'', Montesquieu expounded the separation of powers in government and society. In government, Montesquieu encouraged division into the now standard legislative, judicial and executive branches; in society, he perceived a natural organization into king, the people and the aristocracy, with the latter playing a mediating role. "I do not write to censor that which is established in any country whatsoever," Montesquieu disclaimed in the ''Laws''; however, he did pay special attention to what he felt was the positive example of the constitutional system in England, which in spite of its evolution toward a fusion of powers, had moderated the power of the monarch, and divided Parliament along class lines.

Montesquieu's work had a seminal impact on the American and French revolutionaries. Ironically, the least liberal element of his thought—his privileging of the aristocracy—was belied by both revolutions. Montesquieu's system came to fruition in America, a country with no aristocracy; in France, political maneuvering by the aristocracy led to the convocation of the 1789 Estates-General and popular revolt.

* Some literature:

** ''De l'esprit des lois'', 1748 (''

The Spirit of Law

''The Spirit of Law'' (French: ''De l'esprit des lois'', originally spelled ''De l'esprit des loix''), also known in English as ''The Spirit of heLaws'', is a treatise on political theory, as well as a pioneering work in comparative law by Mont ...

''

** ''

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers'' (together with others), 1751–1772 (Encyclopaedia, or Reasoned Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Trades)

Thomas Gordon

Thomas Gordon (United Kingdom, 169?–1750) was co-author, with John Trenchard of ''Cato's Letters''. These newspaper essays condemned

tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English language, English usage of the word, is an autocracy, absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurper, usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defen ...

and advanced principles of

freedom of conscience

Freedom of conscience is the freedom of an individual to act upon their moral beliefs. In particular, it often refers to the freedom to ''not do'' something one is normally obliged, ordered or expected to do. An individual exercising this freedom m ...

and

freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

and were a main vehicle for spreading the

concept

A concept is an abstract idea that serves as a foundation for more concrete principles, thoughts, and beliefs.

Concepts play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied within such disciplines as linguistics, ...

s that had been developed by

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

.

* Some literature:

** ''

Cato's Letters'' / John Trenchard & Thomas Gordon, 1720–1723

François Quesnay

François Quesnay (France, 1694–1774)

* Some literature:

** ''

Tableau économique'', 1758

** ''

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers'' (together with others), 1751–1772 (Encyclopaedia, or Reasoned Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Trades)

Voltaire

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

(France, 1694–1778)

* Some literature:

** ''Lettres Philosophiques sur les Anglais'', 1734 (Philosophical Letters on the English)

** ''

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers'' (together with others), 1751–1772 (Encyclopaedia, or Reasoned Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Trades)

** ''Essai sur l'histoire génerale et sur les moeurs et l'espirit des nations'', 1756 (Essay on the Manner and Spirit of Nations and on the Principal Occurrences in History)

** ''Traité sur la Tolérance à l'occasion de la mort de Jean Calas'', 1763 (

Treatise on Tolerance on the Occasion of the Death of Jean Calas)

** ''Dictionnaire Philosophique'', 1764 (Philosophical Dictionary)

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

(Switzerland, 1712–1778)

* Some literature:

** ''

Discourse on Inequality

''Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men'' (), also commonly known as the "Second Discourse", is a 1755 treatise by philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, on the topic of social inequality and its origins. The work was written in ...

'', 1755

** ''

On the Social Contract'', 1762

Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during th ...

(France, 1713–1784)

* Some literature:

** ''

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers'' (together with others), 1751–1772 (Encyclopaedia, or Reasoned Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Trades)

Jean le Rond d'Alembert

Jean le Rond d'Alembert

Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert ( ; ; 16 November 1717 – 29 October 1783) was a French mathematician, mechanician, physicist, philosopher, and music theorist. Until 1759 he was, together with Denis Diderot, a co-editor of the ''Encyclopé ...

(France, 1717–1783)

* Some literature:

** ''

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers'' (together with others), 1751–1772 (Encyclopaedia, or Reasoned Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Trades)

Richard Price

Richard Price

Richard Price (23 February 1723 – 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher, Nonconformist minister and mathematician. He was also a political reformer and pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the F ...

(United Kingdom, 1723–1791)

* Some literature:

** ''Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the National Debt'', 1771

** ''Observations on Reversionary Payments'', 1771

** ''Observations on Civil Liberty and the Justice and Policy of the War with America'', 1776

Adam Smith

Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

(Great Britain, 1723–1790), often considered the founder of modern

economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

, was a key figure in formulating and advancing economic doctrine of free trade and competition. In his ''

Wealth of Nations

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', usually referred to by its shortened title ''The Wealth of Nations'', is a book by the Scottish people, Scottish economist and moral philosophy, moral philosopher Adam Smith; ...

'' Adam Smith outlined the key idea that if the economy is basically left to its own devices, limited and finite resources will be put to ultimately their most efficient use through people acting purely in their self-interest. This concept has been quoted out of context by later economists as the

invisible hand

The invisible hand is a metaphor inspired by the Scottish economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith that describes the incentives which free markets sometimes create for self-interested people to accidentally act in the public interest, even ...

of the market.

Smith also advanced property rights and personal

civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties of ...

, including stopping slavery, which today partly form the basic liberal ideology. He was also opposed to stock-holding companies, what today is called a "corporation", because he predicated the self-policing of the free market upon the free association of moral individuals.

* Some literature:

** ''

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', 1776

** ''

The Theory of Moral Sentiments

''The Theory of Moral Sentiments'' is a 1759 book by Adam Smith. It provided the ethical, philosophical, economic, and methodological underpinnings to Smith's later works, including ''The Wealth of Nations'' (1776), '' Essays on Philosophical S ...

'', 1759

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

(Germany, 1724–1804)

* Some literature:

** ''

Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten'', 1785 (Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals)

** ''

Kritik der praktischen Vernunft'', 1788 (Critique of Practical Reason)

** ''Über den Gemeinspruch: Das mag in der Theorie richtig sein, taugt aber nicht für die Praxis'', 1793 (On the common saying: this may be true in theory but it does not apply in practice)

** ''Zum ewigen Frieden'', 1795 (Perpetual Peace)

** ''Metaphysik der Sitten'', 1797 (Metaphysics of Morals)

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot (France, 1727–1781)

* Some literature:

** ''Le Conciliateur'', 1754

** ''Lettre sur la tolérance civile'', 1754

** ''Réflexions sur la formation et la distribution des richesses'', 1766

** '' Lettres sur la liberté du commerce des grains'', 1770

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, English Separatist, separatist theologian, Linguist, grammarian, multi-subject educator and Classical libera ...

(United Kingdom/United States, 1733–1804)

* Some literature:

** ''Essay on the First Principles of Government'', 1768

** ''The Present State of Liberty in Great Britain and her Colonies'', 1769

** ''Remarks on Dr Blackstone's Commentaries'', 1769

** ''Observations on Civil Liberty and the Nature and Justice of the War with America'', 1772

August Ludwig von Schlözer

August Ludwig von Schlözer

August Ludwig von Schlözer (5 July 1735, in Gaggstatt – 9 September 1809, in Göttingen) was a German historian and pedagogist who laid foundations for the critical study of Russian medieval history. He was a member of the Göttingen schoo ...

(Germany, 1735–1809)

Patrick Henry

(United States, 1736–1799)

* Some literature:

** "

Give me liberty or give me death!", 1775

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

(United Kingdom/United States, 1737–1809) was a

Founding Father

The following is a list of national founders of sovereign states who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e., political system ...

, political activist, philosopher, political theorist, and revolutionary. His ideas reflected

Enlightenment-era ideals of human rights. Following the

American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

he returned to England then fled to France, to avoid arrest because advocated the right of the people to overthrow their government. In the ''Age of Reason'', he advocated

Deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin term '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

, promoted reason and freethought, and argued against religion in general and Christian doctrine in particular. In ''Agrarian Justice, opposed to Agrarian Law, and to Agrarian Monopoly'' sought the origins of poverty, locating them in inequitable distribution of land, "a violation of humankind's natural rights," which could be remedied through an estate tax.

* Some literature:

**''

Common Sense

Common sense () is "knowledge, judgement, and taste which is more or less universal and which is held more or less without reflection or argument". As such, it is often considered to represent the basic level of sound practical judgement or know ...

'' (1776)

**''

The American Crisis'' (1776–1783) pamphlets

** ''

Rights of Man'', 1791–92

**''

The Age of Reason'' (1793–1794).

** ''

Agrarian Justice'', 1797

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

(United States, 1743–1826) was the third

President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

and author of the

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

. He also wrote ''

Notes on the State of Virginia'' and the

Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. Ideologically, he was a champion of inalienable individual rights, although excluded women from his formulation, and as a Virginia planter, he held many enslaved persons. He advocated the separation of church and state. His ideas were repeated in many other liberal revolutions around the world, including the (early)

French Revolution.

Works:

*

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

1775

Marquis de Condorcet

Marquis de Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; ; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French Philosophy, philosopher, Political economy, political economist, Politics, politician, and m ...

(France, 1743–1794) advocated for a

liberal economy, free and equal public instruction,

constitutional

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

government, and

equal rights for women and people of all races, which embody the ideals of the

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

.

Some literature:

* ''Esquisse d'un tableau historique des progrés de l'esprit humain'', 1795 (Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind)

Olympe de Gouges

Olympe de Gouges

Olympe de Gouges (; born Marie Gouze; 7 May 17483 November 1793) was a French playwright and political activist. She is best known for her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen and other writings on women's rights and Abol ...

(French, 1748–1793) is best known as an advocate of women's rights, writing ''

Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen'', in response to the ''

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human and civil rights document from the French Revolution; the French title can be translated in the modern era as "Decl ...

'' (1789); she was executed during the

French Revolution. Prior to the outbreak of the revolution, she authored ''Réflexions sur les hommes nègres'' (1788), calling for better treatment of black slaves. Her most famous quote is “A woman has the right to mount the scaffold. She must possess equally the right to mount the speaker's platform.”

Works:

* ''

Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen'' (1791)

* ''La Nécessité du divorce'' (The Necessity of Divorce)’’ 1790

Jeremy Bentham

(England, 1748–1832)

An early advocate of

utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for the affected individuals. In other words, utilitarian ideas encourage actions that lead to the ...

,

animal welfare

Animal welfare is the quality of life and overall well-being of animals. Formal standards of animal welfare vary between contexts, but are debated mostly by animal welfare groups, legislators, and academics. Animal welfare science uses measures ...

and

women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and Entitlement (fair division), entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st c ...

. He had many students all around the world, including

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

and several political leaders. Bentham demanded economic and individual freedom, including the separation of the state and church, freedom of expression, completely equal rights for women, the end of slavery and colonialism, uniform democracy, the abolition of physical punishment of adults and children, the right to divorce, free prices, free trade, and no restrictions on interest. Bentham was not a

libertarian

Libertarianism (from ; or from ) is a political philosophy that holds freedom, personal sovereignty, and liberty as primary values. Many libertarians believe that the concept of freedom is in accord with the Non-Aggression Principle, according ...

: he supported an inheritance tax, restrictions on monopoly power, pensions, health insurance, and other social security, but he called for prudence and careful consideration in any such governmental intervention.

Adamantios Korais

Adamantios Korais

Adamantios Korais (Smyrna, 1748–1833) A major figure of the Greek Enlightenment, Korais helped shape the modern Greek state with his theories on classical education, language, religion, secular law and constitutional government, with passionate views on the necessity of democracy. He corresponded with leading figures of the American republic, especially with Thomas Jefferson.

* Some literature:

** ''Report on the Present State of Civilization in Greece'', 1803

** ''What Should We Greeks Do in the Present Circumstances?'', 1805

** ''The Library of Greek Literature'', 1805–1826

** ''Parerga'', 1809–1827

Emmanuel Sieyès

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès (3 May 174820 June 1836), usually known as the Abbé Sieyès (; ), was a French Catholic priest, ''abbé'', and political writer who was a leading political theorist of the French Revolution (1789–1799); he also held off ...

'(France, 1748–1836) played an important role in the opening years of the

French Revolution, drafting the

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human and civil rights document from the French Revolution; the French title can be translated in the modern era as "Decl ...

, expanding on the theory of

national sovereignty

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are (broadly or ideally) co ...

,

popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

, and

representation implied in his pamphlet ''

What is the Third Estate?''.

Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled ''The Honourable'' from 1762, was a British British Whig Party, Whig politician and statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centurie ...

(United Kingdom, 1749–1806) a

Whig politician and

member of parliament who spent most of his career in opposition. He opposed tyranny of any sort or the threat of it. For this reason he was a staunch critic of

King George III whom he regarded as an aspiring tyrant. He was an

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

and supporter of American Patriots and of the

French Revolution. He attacked

Pitt's wartime legislation and defended the liberty of religious minorities and political radicals. After Pitt's death in January 1806, Fox served briefly as Foreign Secretary in the '

Ministry of All the Talents' of

William Grenville.

* ''The Speeches of the Right Honourable Charles James Fox in the House of Commons''.

Antoine Destutt de Tracy

Antoine Destutt de Tracy (1754–1836)

Stanisław Staszic

Stanisław Staszic

Stanisław Wawrzyniec Staszic (baptised 6 November 1755 – 20 January 1826) was a leading figure in the Polish Enlightenment: a Catholic priest, philosopher, geologist, writer, poet, translator and statesman. A physiocrat, monist, pan-Sla ...

(Poland-Lithuania, 1755–1826) was a Catholic priest, philosopher, geologist, writer, poet, translator and statesman. A physiocrat, monist, pan-Slavist (after 1815) and an advocate of

laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

, he supported many reforms in Poland. He is particularly remembered for his political writings during the "Great (Four-Year) Sejm" (1788–92) and for his support of the Constitution of 3 May 1791.

Friedrich Schiller

Friedrich Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, philosopher and historian. Schiller is considered by most Germans to be Germany's most important classical playwright.

He was born i ...

(Germany, 1759–1805)

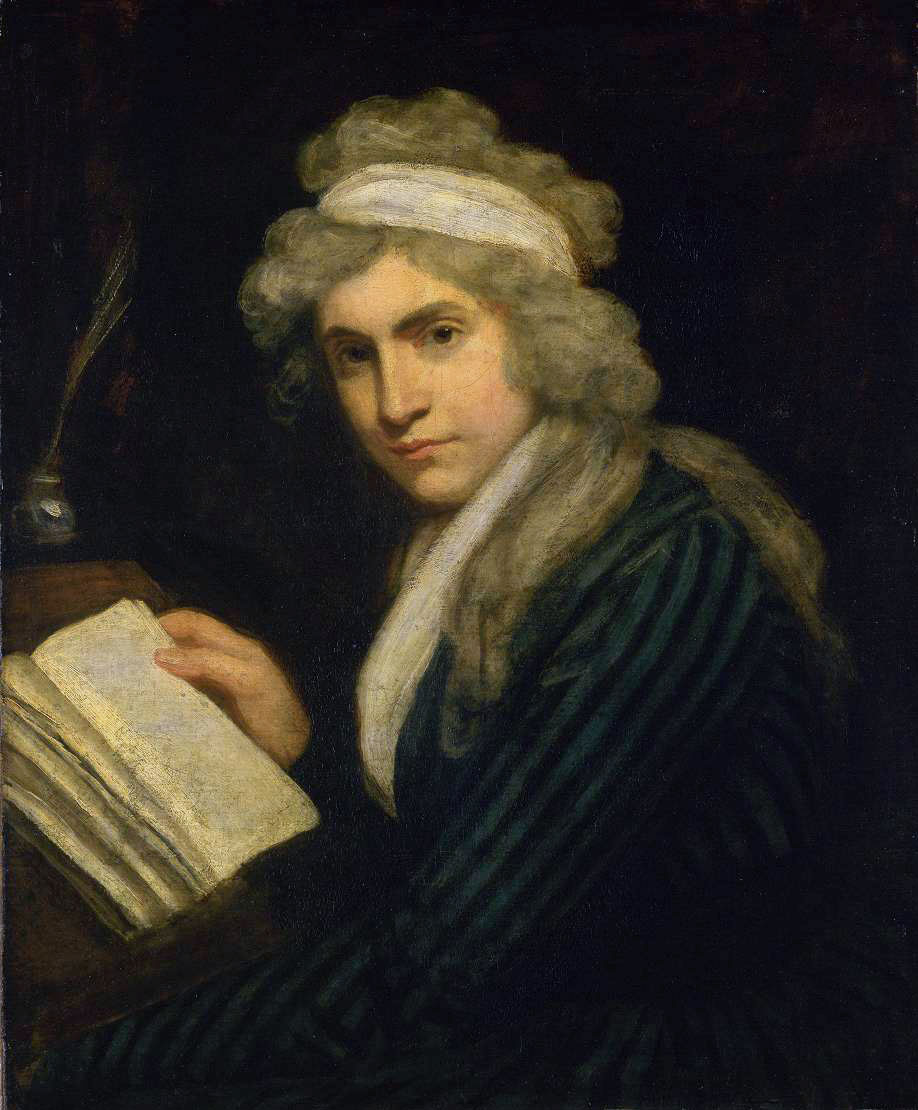

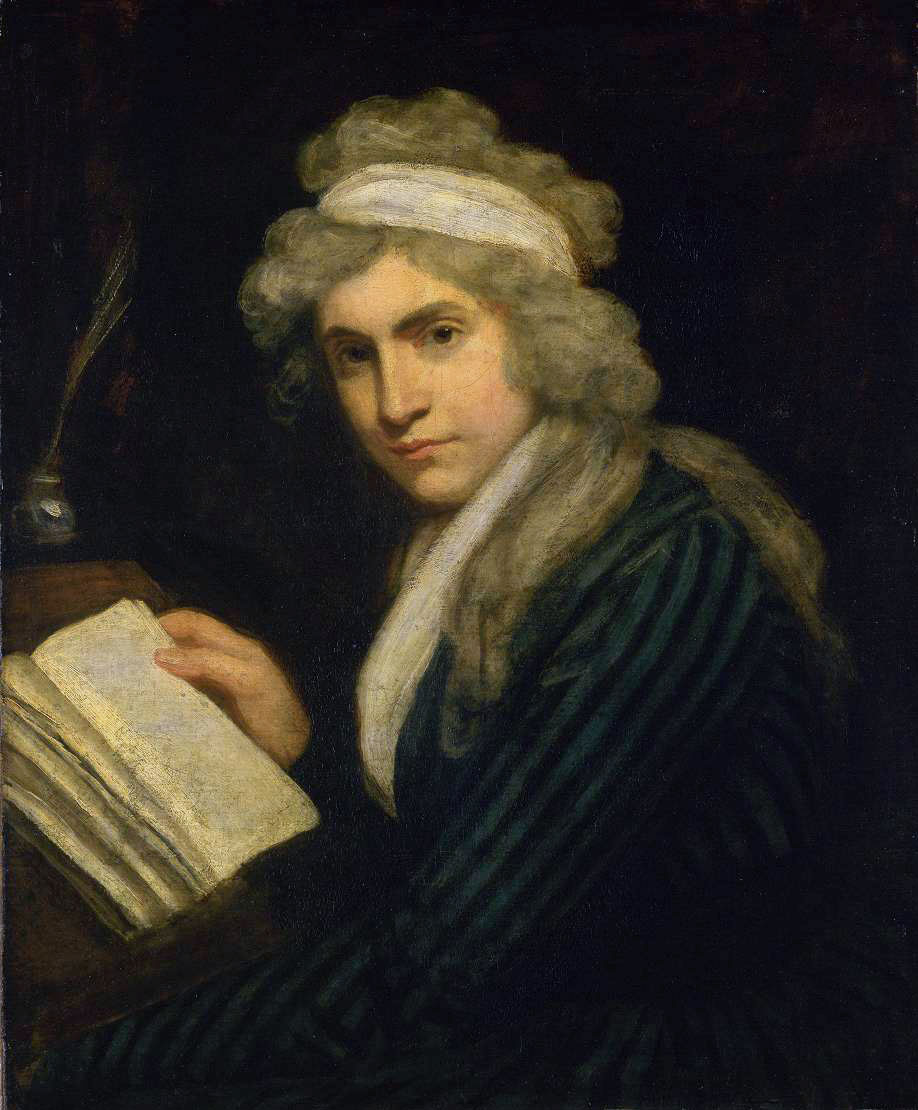

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft ( , ; 27 April 175910 September 1797) was an English writer and philosopher best known for her advocacy of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional ...

(United Kingdom, 1759–1797) is best known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), in which she argues that women are not naturally inferior to men but appear to be only because they lack education. She suggests that both men and women should be treated as rational beings and imagines a social order founded on reason.

Works:

*''

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters'' 1787

*''

A Vindication of the Rights of Men'' 1790

*''

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects'' , is a 1792 feminist essay written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), and is one of the earliest work ...

'' 1792

Anne Louise Germaine de Staël

Anne Louise Germaine de Staël

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie and Ana.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in ...

(France, 1766–1817)

* Some literature:

** ''De l'influence des passions sur le bonheur des individus et des nations'', 1796

** ''Des circonstances actuelles qui peuvent terminer la Révolution et des principes qui doivent fonder la république en France'', 1798

** ''Considérations sur les principaux événements de la révolution française'', 1813

** ''Appel aux souverains réunis à Paris pour en obtenir l'abolition de la traite des nègres'', 1814

Benjamin Constant

Benjamin Constant

Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque (25 October 1767 – 8 December 1830), or simply Benjamin Constant, was a Swiss and French political thinker, activist and writer on political theory and religion.

A committed republican from 1795, Constant ...

(France, 1767–1830) Regarded by some as one of the fathers of modern liberalism, he was initially a republican during the

French Revolution, but utterly rejected

The Jacobins as an instance of the

tyranny of the majority

Tyranny of the majority refers to a situation in majority rule where the preferences and interests of the majority dominate the political landscape, potentially sidelining or repressing minority groups and using majority rule to take non-democrat ...

.

* Some literature:

** ''De l'esprit de conquête et l'usurpation'' (On the spirit of conquest and on usurpation), 1814

** ''Principes de Politique''

Principles of Politics, 1815

** "''

The Liberty of Ancients Compared with that of Moderns,''" 1819

Jean-Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste () is a male French name, originating with Saint John the Baptist, and sometimes shortened to Baptiste. The name may refer to any of the following:

Persons

* Charles XIV John of Sweden, born Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, was K ...

(France, 1767–1832)

* Some literature:

** ''Traité d'économie politique'' (Treatise on Political Economy), 1803.

Wilhelm von Humboldt

Wilhelm von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Christian Karl Ferdinand von Humboldt (22 June 1767 – 8 April 1835) was a German philosopher, linguist, government functionary, diplomat, and founder of the Humboldt University of Berlin. In 1949, the university was named aft ...

(Germany, 1767–1835)

* Some literature:

** ''Ideen zu einem Versuch, die Grenzen der Wirksamkeit des Staats zu bestimmen'' (On the Limits of State Action), 1792.

Adam Czartoryski

Adam Czartoryski (Poland-Lithuania 1770–1867) was a statesman, and international politician. He began as a foreign minister to the Russian Tsar Alexander I and built an anti-Napoleon coalition. He became a leader of the Polish government in exile, and an enemy of Russian Tsar Nicholas I. In exile he was an activist on the Polish Question across Europe, and stimulated early Balkan independence.

* Some literature:

** ''Essai sur la diplomatie'' (Marseilles, 1830);

** ''Life of J. U. Niemcewicz'' (Paris, 1860);

** ''Alexander I. et Czartoryski: correspondence ... et conversations (1801–1823)''

** ''Memoirs of Czartoryski'', with documents relating to his negotiations with Pitt, and conversations with Palmerston in 1832

David Ricardo

David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British political economist, politician, and member of Parliament. He is recognized as one of the most influential classical economists, alongside figures such as Thomas Malthus, Ada ...

(United Kingdom, 1772–1823)

James Mill

James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote '' The History of Britis ...

(United Kingdom, 1773–1836)

* Some literature:

** ''Elements of Political Economy'', 1821

Antoine-Elisée Cherbuliez

Antoine-Elisée Cherbuliez (Switzerland, 1797–1869)

Johan Rudolf Thorbecke

The Dutch statesman

Johan Rudolf Thorbecke (Netherlands, 1798–1872) was the main theorist of Dutch liberalism in the nineteenth century, outlining a more democratic alternative to the absolute monarchy, the constitutional monarchy. The constitution of 1848 was mainly his work. His main theoretical article specifically labeled as 'liberal' was 'Over het hedendaagsche staatsburgerschap' (On Modern Citizenship) from 1844. He became prime minister in 1849, thus starting numerous fundamental reforms in Dutch politics.

Frédéric Bastiat

Frédéric Bastiat (France, 1801–1850)

Claude Frédéric Bastiat was a French classical liberal theorist, political economist, and member of the French assembly.

* Some literature:

** ''La Loi'' (

The Law), 1849

** ''Harmonies économiques'' (Economic Harmonies), 1850

** ''Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas'' (What is Seen and What is Not Seen), 1850

Rifa'a al-Tahtawi

Rifa'a al-Tahtawi (Egypt, 1801–1873)

Rifa'a al-Tahtawi (also spelt Tahtawy) was an

Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...

writer, teacher, translator,

Egyptologist

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , ''-logia''; ) is the scientific study of ancient Egypt. The topics studied include ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end ...

,

renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

intellectual and one of the early adapters to

Islamic Modernism

Islamic modernism is a movement that has been described as "the first Muslim ideological response to the Western cultural challenge", attempting to reconcile the Islamic faith with values perceived as modern such as democracy, civil rights, rati ...

. In 1831, Tahtawi was part of the statewide effort to modernize the Egyptian infrastructure and education. Three of his published volumes were works of political and moral

philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

. They introduced his Egyptian audience to

Enlightenment ideas such as

secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

authority and political rights and liberty; his ideas regarding how a modern civilized society ought to be and what constituted by extension a civilized or "good Egyptian"; and his ideas on public interest and public good. Tahtawi's work was the first effort in what became an Egyptian renaissance (''

nahda

The Nahda (, meaning 'the Awakening'), also referred to as the Arab Awakening or Arab Enlightenment, was a cultural movement that flourished in Arabs, Arab-populated regions of the Ottoman Empire, notably in Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, and Tunisia, ...

'') that flourished in the years between 1860 and 1940.

* Works:

** ''A Paris Profile'', written during Tahtawi's stay in France.

** ''The methodology of Egyptians minds with regard to the marvels of modern literature'', published in 1869 crystallizing Tahtawi's opinions on modernization.

** ''The honest guide for education of girls and boys'', published in 1873 and reflecting the main precepts of Tahtawi's educational thoughts.

** ''Tawfik al-Galil insights into Egypt's and Ismail descendants' history'', the first part of the History Encyclopedia published in 1868 and tracing the history of ancient Egypt till the dawn of Islam.

** ''A thorough summary of the biography of Mohammed'' published after Tahtawi's death, recording a comprehensive account of the life of Prophet Mohammed and the political, legal and administrative foundations of the first Islamic state.

** ''Towards a simpler Arabic grammar'', published in 1869.

** ''Grammatical sentences'', published in 1863.

** ''Egyptian patriotic lyrics'', written in praise of Khedive Said and published in 1855.

** ''The luminous stars in the moonlit nights of al-Aziz'', a collection of congratulatory writings to some princes, published in 1872.

Harriet Martineau

Harriet Martineau

Harriet Martineau (12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876) was an English social theorist.Hill, Michael R. (2002''Harriet Martineau: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives'' Routledge. She wrote from a sociological, holism, holistic, religious and ...

(United Kingdom, 1802–1876)

* Some literature:

** ''Illustrations of Political Economy'', 1832–1834

** ''Theory and Practice of Society in America'', 1837

** ''The Martyr Age of the United States'', 1839

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (29 July 180516 April 1859), was a French Aristocracy (class), aristocrat, diplomat, political philosopher, and historian. He is best known for his works ''Democracy in America'' (appearing in t ...

(France, 1805–1859)

* Some literature:

** ''

De La Démocratie en Amérique'', 1831–1840 (Democracy in America)

** ''L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution'', 1856

Mill and further

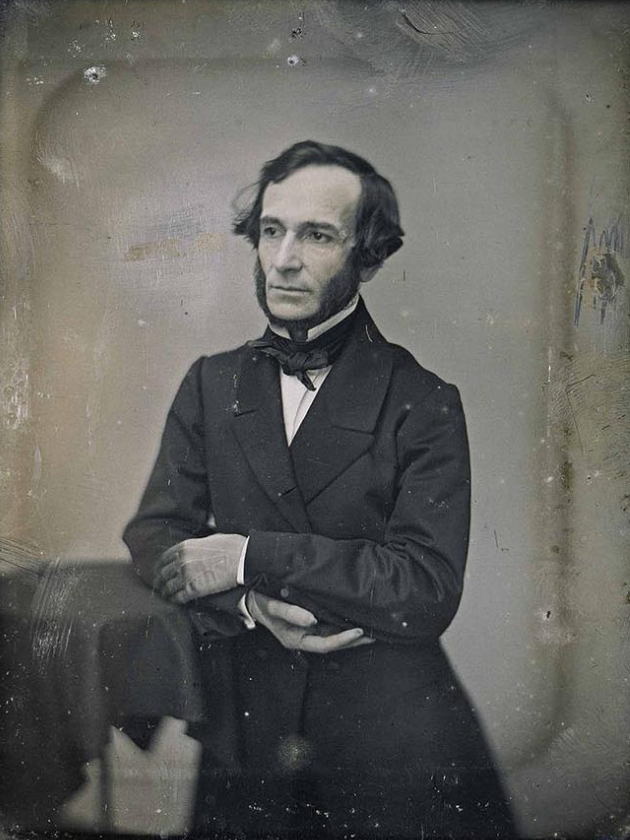

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

(United Kingdom, 1806–1873) is one of the first champions of modern "liberalism." As such, his work on

political economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

and

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

helped lay the foundation for advancements in empirical science and public policy based on verifiable improvements. Strongly influenced by Bentham's

utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for the affected individuals. In other words, utilitarian ideas encourage actions that lead to the ...

, he disagrees with Kant's intuitive notion of right and formulates the "highest normative principle" of morals as:

''Actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness; wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness.''

Some consider Mill as the founder of

Social liberalism

Social liberalism is a political philosophy and variety of liberalism that endorses social justice, social services, a mixed economy, and the expansion of civil and political rights, as opposed to classical liberalism which favors limited g ...

. Although Mill was mainly for

free markets

In economics, a free market is an economic market (economics), system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of ...

, he accepted interventions in the economy, such as a tax on alcohol, if there were sufficient utilitarian grounds. Mill was also a champion of women's rights.

* Some literature:

** ''Considerations On Representative Government'', 1862

** ''On Liberty'', 1868

** ''Socialism'', 1879

José María Luis Mora

José María Luis Mora (New Spain/Mexico 1794 – 1850) was a priest, lawyer, historian, politician and liberal ideologist. Considered one of the first supporters of liberalism in Mexico, he fought for the separation of church and state. Mora has been deemed "the most significant liberal spokesman for his generation [and] his thought epitomizes the structure and the predominant orientation of Mexican liberalism."

Some works:

* ''Catecismo político de la federación mexicana''. Mexico 1831

* ''Disertación sobre la naturaleza y aplicación de las rentas y bienes eclesiásticas, y sobre la autoridad a que se hallan sujetos en cuanto a su creación, aumento, sustencia o supresión''. Mexico 1833.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (United States, 1803–1882) was an American philosopher who argued that the basic principles of government were mutable, and that government is required only insofar as people are not self-governing. Proponent of Democracy, and of the idea that a democratic people must have a democratic ethics.

* Some literature:

** ''Self-Reliance''

** ''Circles''

** ''Politics''

** ''The Nominalist and the Realist''

William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (United States, 1805–1879)

* Some literature:

** Articles advocating abolition of slavery in the newspaper ''The Liberator (anti-slavery newspaper), The Liberator'', 1831–1866

Juan Bautista Alberdi

Juan Bautista Alberdi (Argentina, 1810–1884)

* Some literature:

** ''Bases y puntos de partida para la organización política de la República Argentina'' (Bases and Points of Departure for the Political Organization of the Argentine Republic), 1852

** ''Sistema económico y rentistico de la Confederación Argentina, según su Constitución de 1853'' (Economic and rentistic system of the Argentine Confederation, according to its 1853 Constitution), 1854

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862)

* Some literature:

** ''Civil Disobedience (Thoreau), Civil Disobedience''

** ''Walden''

Jacob Burckhardt

Jacob Burckhardt (Switzerland, 1818–1897) State as derived from cultural and economic life.

* Some literature:

** ''The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy''

Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (United Kingdom, 1820–1903), philosopher, psychologist, and sociologist, advanced what he called the "Law of equal liberty" and argued against liberal theory promoting more activist government, which he dubbed "a new form of Toryism." He supported a state limited in its duties to the defense of persons and their property. For Spencer, voluntary cooperation was the hallmark of the most vibrant form of society, accommodating the widest diversity of members and the greatest diversity of goals. Spencer's evolutionary approach has been characterized as an extension of

Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

's "invisible hand" explanation of economic order; his extensive work on sympathy (in psychology as well as the foundation of ethics, particularly in ''The Data of Ethics'') explicitly carried on Smith's approach in ''

The Theory of Moral Sentiments

''The Theory of Moral Sentiments'' is a 1759 book by Adam Smith. It provided the ethical, philosophical, economic, and methodological underpinnings to Smith's later works, including ''The Wealth of Nations'' (1776), '' Essays on Philosophical S ...

''. Spencer is frequently characterized as a leading Social Darwinism, Social Darwinist.

* Some literature:

** ''Social Statics'', 1851

** ''Principles of Ethics'', 1879, 1892

** ''The Man versus the State'', 1884

** ''Essays, Scientific, Political and Speculative'', 1892

İbrahim Şinasi

İbrahim Şinasi (Ottoman Empire, 1826–1871), author, journalist, translator, and newspaper editor. He was the innovator of several fields: he wrote one of the earliest examples of an Ottoman play, he encouraged the trend of translating poetry from French into Turkish, he simplified the Ottoman Turkish script, script used for writing the Ottoman Turkish language, and he was one of the first of the Ottoman writers to write specifically for the broader public. Şinasi used his newspapers, ''Tercüman-ı Ahvâl'' and ''Tasvîr-i Efkâr'', to promote the proliferation of European

Enlightenment ideals during the Tanzimat, Tanzimat period,

and he made the education of the literate Ottoman public his personal vocation. Though many of Şinasi's projects were incomplete at the time of his death, "he was at the forefront of a number of fields and put his stamp on the development of each field so long as it contained unsolved problems." Şinasi, influenced by Enlightenment thought, saw freedom of expression as a fundamental right and used journalism in order to engage, communicate with, and educate the public. By speaking directly to the public about government affairs, Şinasi declared that state actions were not solely the interest of the government.

[Nergis Ertürk, Grammatology and Literary Modernity in Turkey. Oxford, UK: Oxford UP, 2011. Print.]

* Works:

** ''Tercüme-i Manzume'' (1859, translation of poems from the French of La Fontaine, Lamartine, Gilbert, and Racine)

** '':tr:Şair Evlenmesi, Şair Evlenmesi'' (1859, the first Ottoman play, "The Wedding of a Poet")

** '':tr:Durub-i Emsal-i Osmaniye, Durub-i Emsal-i Osmaniye'' (1863, the first book of Turkish proverbs)

** '':tr:Müntahabat-ı Eş'ar, Müntahabat-ı Eş'ar'' (1863, collection of poems)

Thomas Hill Green

Thomas Hill Green (United Kingdom, 1836–1882)

Auberon Herbert

Auberon Herbert (United Kingdom, 1838–1906)

Carl Menger

Carl Menger (Austria, 1840–1921)

* Some literature:

** ''Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre'' (Principles of Economics), 1871

** ''Untersuchungen über die Methode der Sozialwissenschaften und der Politischen Ökonomie insbesondere'' (Investigations into the Method of the Social Sciences: with special reference to economics), 1883

** ''Irrthumer des Historismus in der deutschen Nationalokonomie'' (The Errors of Historicism in German Economics), 1884

** ''Zur Theorie des Kapitals'' (The Theory of Capital), 1888

William Graham Sumner

William Graham Sumner (United States, 1840–1910)

* Some literature:

** ''Socialism'', 1878

** ''The Argument Against Protective Tariffs'', 1881

** ''Protective Taxes and Wages'', 1883

** ''The Absurd Effort to Make the World Over'', 1883

** ''State Interference'', 1887

** ''Protectionism: the -ism which teaches that waste makes wealth'', 1887

** ''The Forgotten Man, and Other Essays'', 1917

Lester Frank Ward

Lester Frank Ward (United States, 1841–1913)

Lester Ward was a botanist, paleontologist, and sociologist. He served as the first president of the American Sociological Association. Ward was a fierce and unrelenting critic of the laissez-faire policies advocated by Herbert Spencer and William Graham Sumner.

* Some literature:

* (1883) Dynamic Sociology: Or Applied social science as based upon statical sociology and the less complex sciences.

* (1893) The Psychic Factors of Civilization, 1893.

* (1903) Pure Sociology. A Treatise on the Origin and Spontaneous Development of Society.

* (1906) Applied Sociology. A Treatise on the Conscious Improvement of Society by Society.

Ward's major works can be found at the McMaster University, Faculty of Social Sciences website.

Lujo Brentano

Ludwig Joseph Brentano (Germany, 1844–1931)

Tomáš Masaryk

Tomáš Masaryk, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (Czechoslovakia, 1850–1937)

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (Austria, 1851–1914)

* Some literature:

** ''Kapital und Kapitalzins'' (Capital and Interest), in three volumes, 1884, 1889 and 1909

** ''Die Positive Theorie des Kapitals'' (The positive theory of capital and its critics), in three volumes, 1895 and 1896

** ''Zum Abschluss des Marxschen Systems'' (Karl Marx and the Close of his system),1898

Louis Brandeis

Louis Brandeis (1856–1941)

Thorstein Veblen

Thorstein Veblen (1857–1926) is best known as the author of ''Theory of the Leisure Class''. Veblen was influential to a generation of American liberalism searching for a rational basis for the economy beyond corporate consolidation and "cut throat competition". Veblen's central argument was that individuals require sufficient non-economic time to become educated citizens. He caustically attacked pure material consumption for its own sake, and the idea that utility equalled conspicuous consumption.

John Dewey

John Dewey (United States, 1859–1952)

* Some literature:

** ''Liberalism and Social Action'', 1935

** ''Democracy and Education''

Friedrich Naumann

Friedrich Naumann (Germany, 1860–1919)

Santeri Alkio

Santeri Alkio (Finland, 1862–1930)

Max Weber

Max Weber (Germany, 1864–1920) was a theorist of state power and the relationship of culture to economics. Argued that there was a moral component to capitalism rooted in "Protestant" values. Weber was along with Friedrich Naumann active in the National Social Union and later in the German Democratic Party.

* Some literature:

** ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Die protestantische Ethik und der 'Geist' des Kapitalismus'', 1904 (The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

Leonard Hobhouse

Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse (United Kingdom, 1864–1929)

* Some literature:

** ''Liberalism'', 1911

Benedetto Croce

Benedetto Croce (Italy, 1866–1952)

* Some literature:

** ''Che cosa è il liberalismo'', 1943

Walther Rathenau

Walther Rathenau (Germany, 1867–1922)

Sir Leo Chiozza Money

Leo Chiozza Money (Britain, 1870–1944)

An Italian-born economic theorist who moved to Britain in the 1890s, where he made his name as a politician, journalist and author. In the early years of the 20th century his views attracted the interest of two future Prime Ministers, David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill. After a spell as Lloyd George's parliamentary private secretary, he was a Government minister in the latter stages of the First World War.

Ahmed Lutfi el-Sayed

Ahmed Lutfi el-Sayed Pasha (Egypt, 1872–1963)

An

Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...