Continuous permafrost on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Permafrost () is

Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change

I

Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[Masson-Delmotte, V.; P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, USA, pp. 1211–1362. Instead, the annual permafrost emissions are likely comparable with global emissions from deforestation, or to annual emissions of large countries such as Greenhouse gas emissions by Russia, Russia, the

The below-ground temperature varies less from season to season than the air temperature, with mean annual temperatures tending to increase with depth due to the geothermal crustal gradient. Thus, if the mean annual air temperature is only slightly below , permafrost will form only in spots that are sheltered (usually with a northern or southern aspect, in the north and south hemispheres respectively) creating discontinuous permafrost. Usually, permafrost will remain discontinuous in a climate where the mean annual soil surface temperature is between . In the moist-wintered areas mentioned before, there may not even be discontinuous permafrost down to . Discontinuous permafrost is often further divided into extensive discontinuous permafrost, where permafrost covers between 50 and 90 percent of the landscape and is usually found in areas with mean annual temperatures between , and sporadic permafrost, where permafrost cover is less than 50 percent of the landscape and typically occurs at mean annual temperatures between .

In soil science, the sporadic permafrost zone is abbreviated SPZ and the extensive discontinuous permafrost zone DPZ. Exceptions occur in un-glaciated

The below-ground temperature varies less from season to season than the air temperature, with mean annual temperatures tending to increase with depth due to the geothermal crustal gradient. Thus, if the mean annual air temperature is only slightly below , permafrost will form only in spots that are sheltered (usually with a northern or southern aspect, in the north and south hemispheres respectively) creating discontinuous permafrost. Usually, permafrost will remain discontinuous in a climate where the mean annual soil surface temperature is between . In the moist-wintered areas mentioned before, there may not even be discontinuous permafrost down to . Discontinuous permafrost is often further divided into extensive discontinuous permafrost, where permafrost covers between 50 and 90 percent of the landscape and is usually found in areas with mean annual temperatures between , and sporadic permafrost, where permafrost cover is less than 50 percent of the landscape and typically occurs at mean annual temperatures between .

In soil science, the sporadic permafrost zone is abbreviated SPZ and the extensive discontinuous permafrost zone DPZ. Exceptions occur in un-glaciated

Subsea permafrost occurs beneath the

Subsea permafrost occurs beneath the

When the ice content of a permafrost exceeds 250 percent (ice to dry soil by mass) it is classified as massive ice. Massive ice bodies can range in composition, in every conceivable gradation from icy

When the ice content of a permafrost exceeds 250 percent (ice to dry soil by mass) it is classified as massive ice. Massive ice bodies can range in composition, in every conceivable gradation from icy

File:Palsaaerialview.jpg, A group of palsas, as seen from above, formed by the growth of ice lenses.

File:Injection ice in a pingo.jpg, Injection ice in a pingo, Mackenzie delta area.

File:Pingos near Tuk.jpg, Pingos near

Only plants with shallow

Only plants with shallow  While permafrost soil is frozen, it is not completely inhospitable to

While permafrost soil is frozen, it is not completely inhospitable to

File:PICT4417Sykhus.JPG, A building on elevated piles in permafrost zone.

File:Trans-Alaska Pipeline (1).jpg, Heat pipe#Permafrost cooling, Heat pipes in vertical supports maintain a frozen bulb around portions of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline that are at risk of thawing.

File:Yakoutsk Construction d'immeuble.jpg, Pile foundations in Yakutsk, a city underlain with continuous permafrost.

File:Raised pipes in permafrost.jpg, District heating pipes run above ground in Yakutsk.

Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change

I

''Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change''.

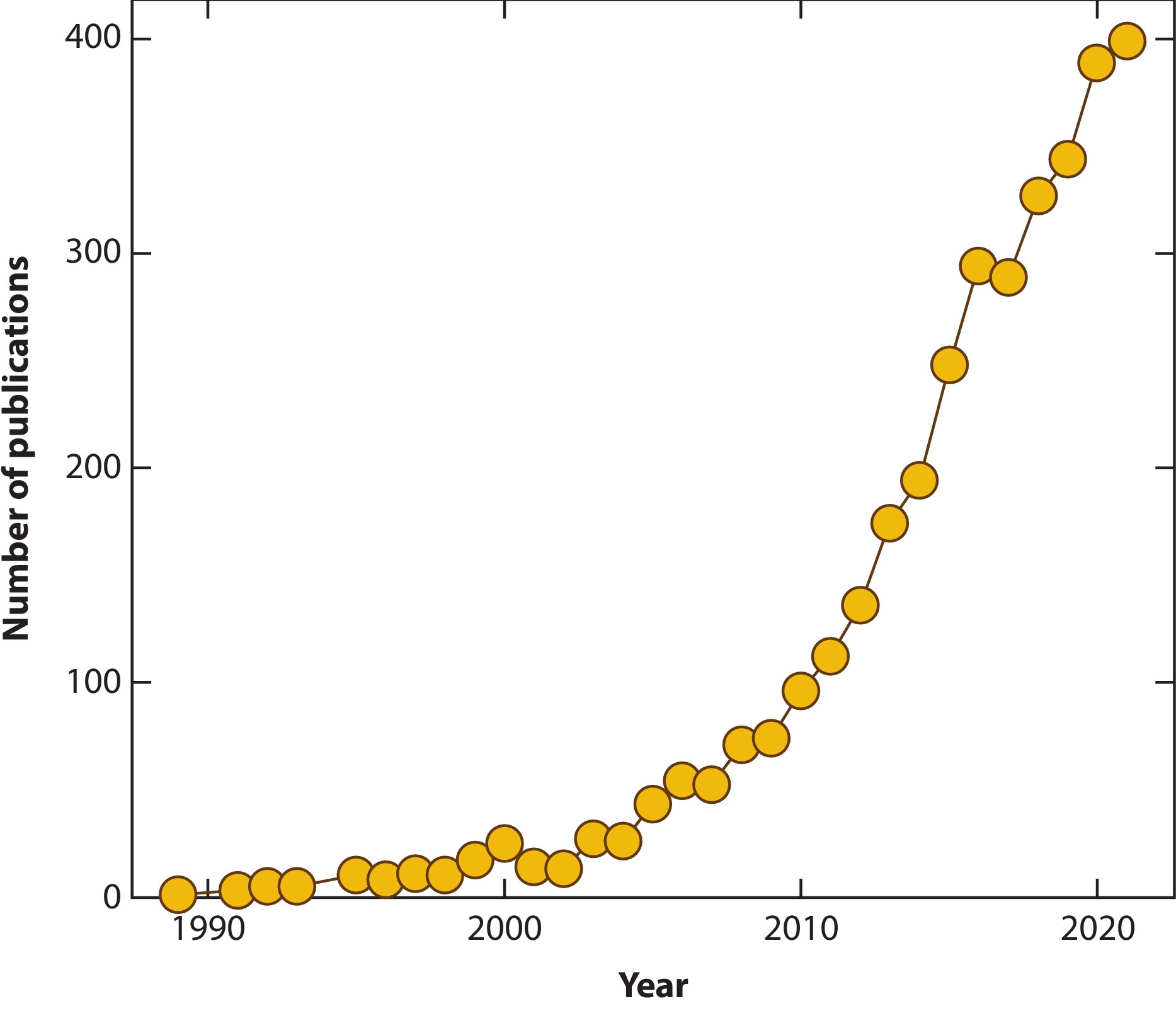

[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.011. Between 2000 and 2018, the average active layer thickness had increased from ~ to ~, at an average annual rate of ~. In Yukon, the zone of continuous permafrost might have moved poleward since 1899, but accurate records only go back 30 years. The extent of subsea permafrost is decreasing as well; as of 2019, ~97% of permafrost under Arctic ice shelves is becoming warmer and thinner. Based on high agreement across model projections, fundamental process understanding, and paleoclimate evidence, it is virtually certain that permafrost extent and volume will continue to shrink as the global climate warms, with the extent of the losses determined by the magnitude of warming. Permafrost thaw is associated with a wide range of issues, and International Permafrost Association (IPA) exists to help address them. It convenes International Permafrost Conferences and maintains Global Terrestrial Network for Permafrost, which undertakes special projects such as preparing databases, maps, bibliographies, and glossaries, and coordinates international field programmes and networks.

As recent warming deepens the active layer subject to permafrost thaw, this exposes formerly stored

As recent warming deepens the active layer subject to permafrost thaw, this exposes formerly stored  In the northern circumpolar region, permafrost contains organic matter equivalent to 1400–1650 billion tons of pure carbon, which was built up over thousands of years. This amount equals almost half of all organic material in all

In the northern circumpolar region, permafrost contains organic matter equivalent to 1400–1650 billion tons of pure carbon, which was built up over thousands of years. This amount equals almost half of all organic material in all

Summary for Policymakers

(archive

16 July 2014

, in: about 5% to 15% of permafrost carbon is expected to be lost "over decades and centuries". The exact amount of carbon that will be released due to warming in a given permafrost area depends on depth of thaw, carbon content within the thawed soil, physical changes to the environment, and microbial and vegetation activity in the soil. Notably, estimates of carbon release alone do not fully represent the impact of permafrost thaw on climate change. This is because carbon can be released through either aerobic respiration, aerobic or anaerobic respiration, which results in carbon dioxide (CO2) or methane (CH4) emissions, respectively. While methane lasts less than 12 years in the atmosphere, its global warming potential is around 80 times larger than that of CO2 over a 20-year period and about 28 times larger over a 100-year period. While only a small fraction of permafrost carbon will enter the atmosphere as methane, those emissions will cause 40–70% of the total warming caused by permafrost thaw during the 21st century. Much of the uncertainty about the eventual extent of permafrost methane emissions is caused by the difficulty of accounting for the recently discovered abrupt thaw processes, which often increase the fraction of methane emitted over carbon dioxide in comparison to the usual gradual thaw processes. Another factor which complicates projections of permafrost carbon emissions is the ongoing "greening" of the Arctic. As climate change warms the air and the soil, the region becomes more hospitable to plants, including larger shrubs and trees which could not survive there before. Thus, the Arctic is losing more and more of its

Another factor which complicates projections of permafrost carbon emissions is the ongoing "greening" of the Arctic. As climate change warms the air and the soil, the region becomes more hospitable to plants, including larger shrubs and trees which could not survive there before. Thus, the Arctic is losing more and more of its

Altogether, it is expected that cumulative greenhouse gas emissions from permafrost thaw will be smaller than the cumulative anthropogenic emissions, yet still substantial on a global scale, with some experts comparing them to emissions caused by deforestation. The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report estimates that carbon dioxide and methane released from permafrost could amount to the equivalent of 14–175 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide per of warming. For comparison, by 2019, annual anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide alone stood around 40 billion tonnes. A major review published in the year 2022 concluded that if the goal of preventing of warming was realized, then the average annual permafrost emissions throughout the 21st century would be equivalent to the year 2019 annual emissions of Russia. Under RCP4.5, a scenario considered close to the current trajectory and where the warming stays slightly below , annual permafrost emissions would be comparable to year 2019 emissions of Western Europe or the United States, while under the scenario of high global warming and worst-case permafrost feedback response, they would approach year 2019 emissions of China.

Fewer studies have attempted to describe the impact directly in terms of warming. A 2018 paper estimated that if global warming was limited to , gradual permafrost thaw would add around to global temperatures by 2100, while a 2022 review concluded that every of global warming would cause and from abrupt thaw by the year 2100 and 2300. Around of global warming, abrupt (around 50 years) and widespread collapse of permafrost areas could occur, resulting in an additional warming of .

Altogether, it is expected that cumulative greenhouse gas emissions from permafrost thaw will be smaller than the cumulative anthropogenic emissions, yet still substantial on a global scale, with some experts comparing them to emissions caused by deforestation. The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report estimates that carbon dioxide and methane released from permafrost could amount to the equivalent of 14–175 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide per of warming. For comparison, by 2019, annual anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide alone stood around 40 billion tonnes. A major review published in the year 2022 concluded that if the goal of preventing of warming was realized, then the average annual permafrost emissions throughout the 21st century would be equivalent to the year 2019 annual emissions of Russia. Under RCP4.5, a scenario considered close to the current trajectory and where the warming stays slightly below , annual permafrost emissions would be comparable to year 2019 emissions of Western Europe or the United States, while under the scenario of high global warming and worst-case permafrost feedback response, they would approach year 2019 emissions of China.

Fewer studies have attempted to describe the impact directly in terms of warming. A 2018 paper estimated that if global warming was limited to , gradual permafrost thaw would add around to global temperatures by 2100, while a 2022 review concluded that every of global warming would cause and from abrupt thaw by the year 2100 and 2300. Around of global warming, abrupt (around 50 years) and widespread collapse of permafrost areas could occur, resulting in an additional warming of .

As the water drains or evaporates, soil structure weakens and sometimes becomes viscous until it regains strength with decreasing moisture content. One visible sign of permafrost degradation is the Drunken trees, random displacement of trees from their vertical orientation in permafrost areas. Global warming has been increasing permafrost slope disturbances and sediment supplies to fluvial systems, resulting in exceptional increases in river sediment. On the other hands, disturbance of formerly hard soil increases drainage of water reservoirs in northern wetlands. This can dry them out and compromise the survival of plants and animals used to the wetland ecosystem.

In high mountains, much of the structural stability can be attributed to

As the water drains or evaporates, soil structure weakens and sometimes becomes viscous until it regains strength with decreasing moisture content. One visible sign of permafrost degradation is the Drunken trees, random displacement of trees from their vertical orientation in permafrost areas. Global warming has been increasing permafrost slope disturbances and sediment supplies to fluvial systems, resulting in exceptional increases in river sediment. On the other hands, disturbance of formerly hard soil increases drainage of water reservoirs in northern wetlands. This can dry them out and compromise the survival of plants and animals used to the wetland ecosystem.

In high mountains, much of the structural stability can be attributed to  Permafrost thaw can also result in the formation of frozen debris lobes (FDLs), which are defined as "slow-moving landslides composed of soil, rocks, trees, and ice". This is a notable issue in the

Permafrost thaw can also result in the formation of frozen debris lobes (FDLs), which are defined as "slow-moving landslides composed of soil, rocks, trees, and ice". This is a notable issue in the

As of 2021, there are 1162 settlements located directly atop the Arctic permafrost, which host an estimated 5 million people. By 2050, permafrost layer below 42% of these settlements is expected to thaw, affecting all their inhabitants (currently 3.3 million people). Consequently, a wide range of infrastructure in permafrost areas is threatened by the thaw. By 2050, it's estimated that nearly 70% of global infrastructure located in the permafrost areas would be at high risk of permafrost thaw, including 30–50% of "critical" infrastructure. The associated costs could reach tens of billions of dollars by the second half of the century. Reducing

As of 2021, there are 1162 settlements located directly atop the Arctic permafrost, which host an estimated 5 million people. By 2050, permafrost layer below 42% of these settlements is expected to thaw, affecting all their inhabitants (currently 3.3 million people). Consequently, a wide range of infrastructure in permafrost areas is threatened by the thaw. By 2050, it's estimated that nearly 70% of global infrastructure located in the permafrost areas would be at high risk of permafrost thaw, including 30–50% of "critical" infrastructure. The associated costs could reach tens of billions of dollars by the second half of the century. Reducing  Outside of the Arctic, Qinghai–Tibet Plateau (sometimes known as "the Third Pole"), also has an extensive permafrost area. It is warming at twice the global average rate, and 40% of it is already considered "warm" permafrost, making it particularly unstable. Qinghai–Tibet Plateau has a population of over 10 million people – double the population of permafrost regions in the Arctic – and over 1 million m2 of buildings are located in its permafrost area, as well as 2,631 km of power lines, and 580 km of railways. There are also 9,389 km of roads, and around 30% are already sustaining damage from permafrost thaw. Estimates suggest that under the scenario most similar to today, Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, SSP2-4.5, around 60% of the current infrastructure would be at high risk by 2090 and simply maintaining it would cost $6.31 billion, with adaptation reducing these costs by 20.9% at most. Holding the global warming to would reduce these costs to $5.65 billion, and fulfilling the optimistic Paris Agreement target of would save a further $1.32 billion. In particular, fewer than 20% of railways would be at high risk by 2100 under , yet this increases to 60% at , while under SSP5-8.5, this level of risk is met by mid-century.

Outside of the Arctic, Qinghai–Tibet Plateau (sometimes known as "the Third Pole"), also has an extensive permafrost area. It is warming at twice the global average rate, and 40% of it is already considered "warm" permafrost, making it particularly unstable. Qinghai–Tibet Plateau has a population of over 10 million people – double the population of permafrost regions in the Arctic – and over 1 million m2 of buildings are located in its permafrost area, as well as 2,631 km of power lines, and 580 km of railways. There are also 9,389 km of roads, and around 30% are already sustaining damage from permafrost thaw. Estimates suggest that under the scenario most similar to today, Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, SSP2-4.5, around 60% of the current infrastructure would be at high risk by 2090 and simply maintaining it would cost $6.31 billion, with adaptation reducing these costs by 20.9% at most. Holding the global warming to would reduce these costs to $5.65 billion, and fulfilling the optimistic Paris Agreement target of would save a further $1.32 billion. In particular, fewer than 20% of railways would be at high risk by 2100 under , yet this increases to 60% at , while under SSP5-8.5, this level of risk is met by mid-century.

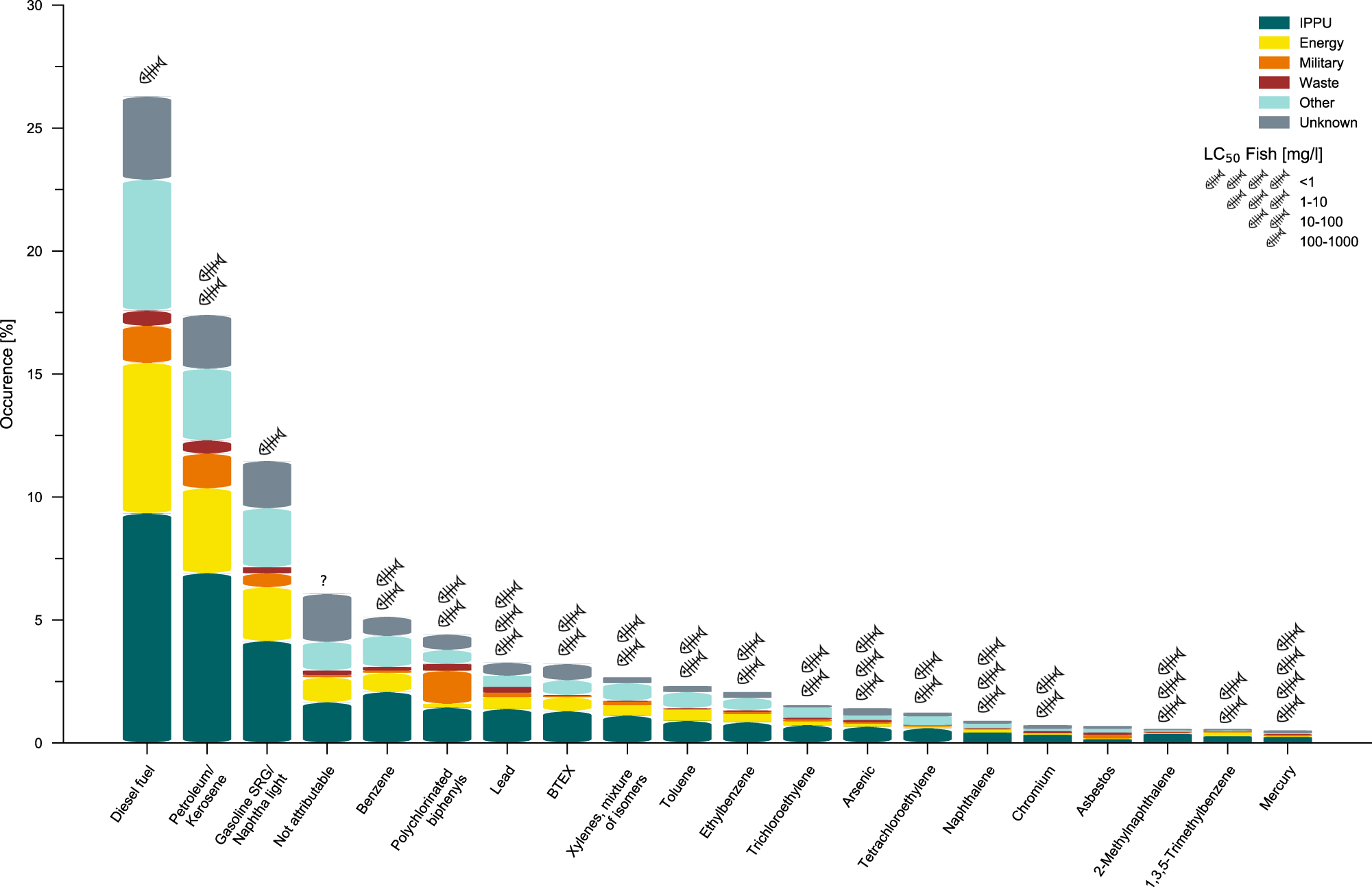

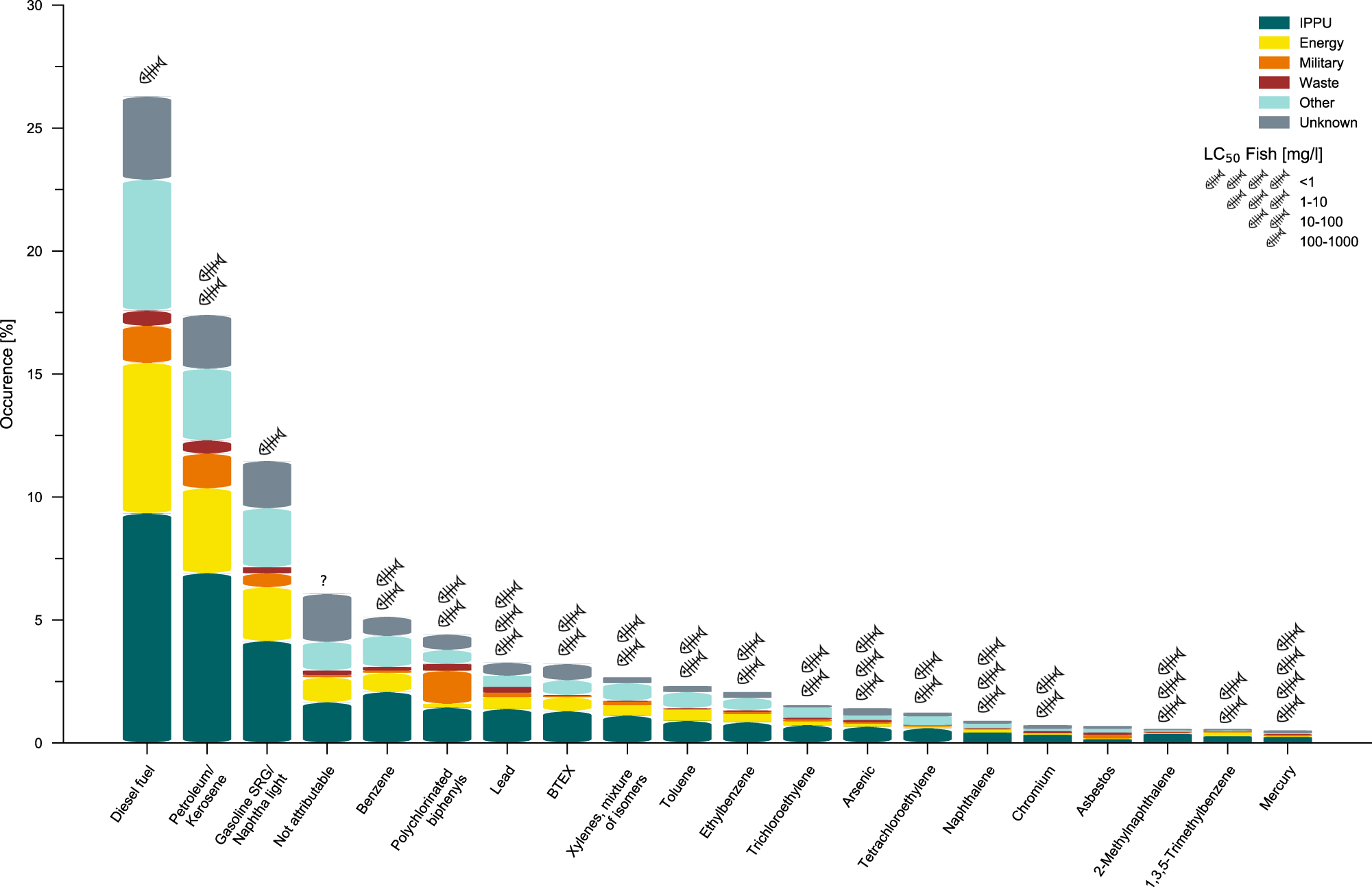

For much of the 20th century, it was believed that permafrost would "indefinitely" preserve anything buried there, and this made deep permafrost areas popular locations for hazardous waste disposal. In places like Canada's Prudhoe Bay oil field, procedures were developed documenting the "appropriate" way to inject waste beneath the permafrost. This means that as of 2023, there are ~4500 industrial facilities in the Arctic permafrost areas which either actively process or store hazardous chemicals. Additionally, there are between 13,000 and 20,000 sites which have been heavily contaminated, 70% of them in Russia, and their pollution is currently trapped in the permafrost.

About a fifth of both the industrial and the polluted sites (1000 and 2200–4800) are expected to start thawing in the future even if the warming does not increase from its 2020 levels. Only about 3% more sites would start thawing between now and 2050 under the climate change scenario consistent with the Paris Agreement goals, Representative Concentration Pathway, RCP2.6, but by 2100, about 1100 more industrial facilities and 3500 to 5200 contaminated sites are expected to start thawing even then. Under the very high emission scenario RCP8.5, 46% of industrial and contaminated sites would start thawing by 2050, and virtually all of them would be affected by the thaw by 2100.

Organochlorines and other persistent organic pollutants are of a particular concern, due to their potential to repeatedly reach local communities after their re-release through biomagnification in fish. At worst, future generations born in the Arctic would enter life with weakened immune systems due to pollutants accumulating across generations.

For much of the 20th century, it was believed that permafrost would "indefinitely" preserve anything buried there, and this made deep permafrost areas popular locations for hazardous waste disposal. In places like Canada's Prudhoe Bay oil field, procedures were developed documenting the "appropriate" way to inject waste beneath the permafrost. This means that as of 2023, there are ~4500 industrial facilities in the Arctic permafrost areas which either actively process or store hazardous chemicals. Additionally, there are between 13,000 and 20,000 sites which have been heavily contaminated, 70% of them in Russia, and their pollution is currently trapped in the permafrost.

About a fifth of both the industrial and the polluted sites (1000 and 2200–4800) are expected to start thawing in the future even if the warming does not increase from its 2020 levels. Only about 3% more sites would start thawing between now and 2050 under the climate change scenario consistent with the Paris Agreement goals, Representative Concentration Pathway, RCP2.6, but by 2100, about 1100 more industrial facilities and 3500 to 5200 contaminated sites are expected to start thawing even then. Under the very high emission scenario RCP8.5, 46% of industrial and contaminated sites would start thawing by 2050, and virtually all of them would be affected by the thaw by 2100.

Organochlorines and other persistent organic pollutants are of a particular concern, due to their potential to repeatedly reach local communities after their re-release through biomagnification in fish. At worst, future generations born in the Arctic would enter life with weakened immune systems due to pollutants accumulating across generations.

A notable example of pollution risks associated with permafrost was the 2020 Norilsk oil spill, caused by the collapse of diesel fuel storage tank at Norilsk-Taimyr Energy's thermal power plant No. 3. It spilled 6,000 tonnes of fuel into the land and 15,000 into the water, polluting Ambarnaya, Daldykan and many smaller rivers on Taimyr Peninsula, even reaching lake Pyasino, which is a crucial water source in the area. State of emergency at the federal level was declared. The event has been described as the second-largest oil spill in modern Russian history.

Another issue associated with permafrost thaw is the release of natural mercury deposits. An estimated 800,000 tons of mercury are frozen in the permafrost soil. According to observations, around 70% of it is simply taken up by vegetation after the thaw. However, if the warming continues under RCP8.5, then permafrost emissions of mercury into the atmosphere would match the current global emissions from all human activities by 2200. Mercury-rich soils also pose a much greater threat to humans and the environment if they thaw near rivers. Under RCP8.5, enough mercury will enter the Yukon River basin by 2050 to make its fish unsafe to eat under the EPA guidelines. By 2100, mercury concentrations in the river will double. Contrastingly, even if mitigation is limited to RCP4.5 scenario, mercury levels will increase by about 14% by 2100, and will not breach the EPA guidelines even by 2300.

A notable example of pollution risks associated with permafrost was the 2020 Norilsk oil spill, caused by the collapse of diesel fuel storage tank at Norilsk-Taimyr Energy's thermal power plant No. 3. It spilled 6,000 tonnes of fuel into the land and 15,000 into the water, polluting Ambarnaya, Daldykan and many smaller rivers on Taimyr Peninsula, even reaching lake Pyasino, which is a crucial water source in the area. State of emergency at the federal level was declared. The event has been described as the second-largest oil spill in modern Russian history.

Another issue associated with permafrost thaw is the release of natural mercury deposits. An estimated 800,000 tons of mercury are frozen in the permafrost soil. According to observations, around 70% of it is simply taken up by vegetation after the thaw. However, if the warming continues under RCP8.5, then permafrost emissions of mercury into the atmosphere would match the current global emissions from all human activities by 2200. Mercury-rich soils also pose a much greater threat to humans and the environment if they thaw near rivers. Under RCP8.5, enough mercury will enter the Yukon River basin by 2050 to make its fish unsafe to eat under the EPA guidelines. By 2100, mercury concentrations in the river will double. Contrastingly, even if mitigation is limited to RCP4.5 scenario, mercury levels will increase by about 14% by 2100, and will not breach the EPA guidelines even by 2300.

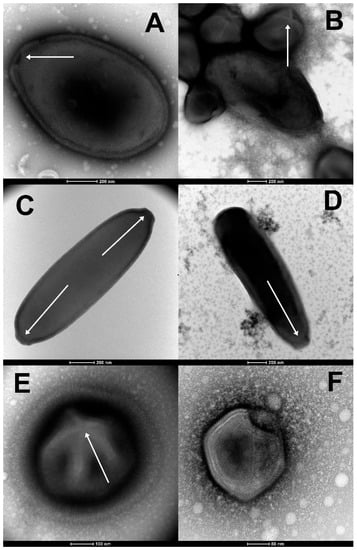

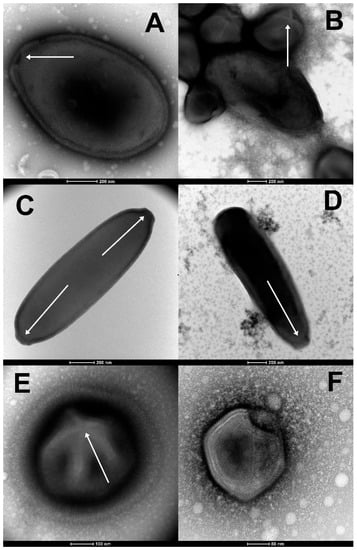

Bacteria are known for being able to Dormancy#Bacteria, remain dormant to survive adverse conditions, and viruses are not metabolically active outside of host cells in the first place. This has motivated concerns that permafrost thaw could free previously unknown microorganisms, which may be capable of infecting either humans or important livestock and crops, potentially resulting in damaging epidemics or

Bacteria are known for being able to Dormancy#Bacteria, remain dormant to survive adverse conditions, and viruses are not metabolically active outside of host cells in the first place. This has motivated concerns that permafrost thaw could free previously unknown microorganisms, which may be capable of infecting either humans or important livestock and crops, potentially resulting in damaging epidemics or

Baer is also known to have composed the world's first permafrost textbook in 1843, (''Materials for the study of the perennial ground-ice in Siberia''), written in his native German. However, it was not printed then, and a Russian translation was not ready until 1942. The original German textbook was believed to be lost until the manuscript, typescript from 1843 was discovered in the library archives of the University of Giessen. The 234-page text was available online, with additional maps, preface and comments. Notably, Baer's southern limit of permafrost in Eurasia drawn in 1843 corresponds well with the actual southern limit verified by modern research.

Beginning in 1942, Siemon William Muller delved into the relevant Russian literature held by the Library of Congress and the United States Geological Survey Library, U.S. Geological Survey Library so that he was able to furnish the government an engineering field guide and a technical report about permafrost by 1943. That report coined the English term as a contraction of permanently frozen ground, in what was considered a direct translation of the Russian term (). In 1953, this translation was criticized by another USGS researcher Inna Poiré, as she believed the term had created unrealistic expectations about its stability: more recently, some researchers have argued that "perpetually refreezing" would be a more suitable translation. The report itself was classified (as U.S. Army. Office of the Chief of Engineers, ''Strategic Engineering Study'', no. 62, 1943), until a revised version was released in 1947, which is regarded as the first North American treatise on the subject.

Baer is also known to have composed the world's first permafrost textbook in 1843, (''Materials for the study of the perennial ground-ice in Siberia''), written in his native German. However, it was not printed then, and a Russian translation was not ready until 1942. The original German textbook was believed to be lost until the manuscript, typescript from 1843 was discovered in the library archives of the University of Giessen. The 234-page text was available online, with additional maps, preface and comments. Notably, Baer's southern limit of permafrost in Eurasia drawn in 1843 corresponds well with the actual southern limit verified by modern research.

Beginning in 1942, Siemon William Muller delved into the relevant Russian literature held by the Library of Congress and the United States Geological Survey Library, U.S. Geological Survey Library so that he was able to furnish the government an engineering field guide and a technical report about permafrost by 1943. That report coined the English term as a contraction of permanently frozen ground, in what was considered a direct translation of the Russian term (). In 1953, this translation was criticized by another USGS researcher Inna Poiré, as she believed the term had created unrealistic expectations about its stability: more recently, some researchers have argued that "perpetually refreezing" would be a more suitable translation. The report itself was classified (as U.S. Army. Office of the Chief of Engineers, ''Strategic Engineering Study'', no. 62, 1943), until a revised version was released in 1947, which is regarded as the first North American treatise on the subject.

Between 11 and 15 November 1963, the First International Conference on Permafrost took place on the grounds of Purdue University in the American town of West Lafayette, Indiana. It involved 285 participants (including "engineers, manufacturers and builders" who attended alongside the researchers) from a range of countries (Argentina, Austria, Canada, Germany, Great Britain, Japan,

Between 11 and 15 November 1963, the First International Conference on Permafrost took place on the grounds of Purdue University in the American town of West Lafayette, Indiana. It involved 285 participants (including "engineers, manufacturers and builders" who attended alongside the researchers) from a range of countries (Argentina, Austria, Canada, Germany, Great Britain, Japan,

Climate Change 2013 Working Group 1 website.

*

International Permafrost Association (IPA)

Permafrost – what is it? – Alfred Wegener Institute YouTube video

{{Authority control Permafrost, 1940s neologisms Cryosphere Geography of the Arctic Geomorphology Montane ecology Patterned grounds Pedology Periglacial landforms

soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, water, and organisms that together support the life of plants and soil organisms. Some scientific definitions distinguish dirt from ''soil'' by re ...

or underwater sediment

Sediment is a solid material that is transported to a new location where it is deposited. It occurs naturally and, through the processes of weathering and erosion, is broken down and subsequently sediment transport, transported by the action of ...

which continuously remains below for two years or more; the oldest permafrost has been continuously frozen for around 700,000 years. Whilst the shallowest permafrost has a vertical extent of below a meter (3 ft), the deepest is greater than . Similarly, the area of individual permafrost zones may be limited to narrow mountain summit

A summit is a point on a surface that is higher in elevation than all points immediately adjacent to it. The topographic terms acme, apex, peak (mountain peak), and zenith are synonymous.

The term (mountain top) is generally used only for ...

s or extend across vast Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

regions. The ground beneath glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

s and ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacier, glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are the Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet. Ice s ...

s is not usually defined as permafrost, so on land, permafrost is generally located beneath a so-called active layer of soil which freezes and thaws depending on the season.

Around 15% of the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

or 11% of the global surface is underlain by permafrost, covering a total area of around . This includes large areas of Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

, and Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. It is also located in high mountain regions, with the Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or Qingzang Plateau, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central Asia, Central, South Asia, South, and East Asia. Geographically, it is located to the north of H ...

being a prominent example. Only a minority of permafrost exists in the Southern Hemisphere, where it is consigned to mountain slopes like in the Andes

The Andes ( ), Andes Mountains or Andean Mountain Range (; ) are the List of longest mountain chains on Earth, longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range ...

of Patagonia

Patagonia () is a geographical region that includes parts of Argentina and Chile at the southern end of South America. The region includes the southern section of the Andes mountain chain with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and glaciers ...

, the Southern Alps

The Southern Alps (; officially Southern Alps / Kā Tiritiri o te Moana) are a mountain range extending along much of the length of New Zealand, New Zealand's South Island, reaching its greatest elevations near the range's western side. The n ...

of New Zealand, or the highest mountains of Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

.

Permafrost contains large amounts of dead biomass

Biomass is a term used in several contexts: in the context of ecology it means living organisms, and in the context of bioenergy it means matter from recently living (but now dead) organisms. In the latter context, there are variations in how ...

that has accumulated throughout millennia without having had the chance to fully decompose and release its carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

, making tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

soil a carbon sink

A carbon sink is a natural or artificial carbon sequestration process that "removes a greenhouse gas, an aerosol or a precursor of a greenhouse gas from the atmosphere". These sinks form an important part of the natural carbon cycle. An overar ...

. As global warming

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes ...

heats the ecosystem, frozen soil thaws and becomes warm enough for decomposition to start anew, accelerating the permafrost carbon cycle

The permafrost carbon cycle or Arctic carbon cycle is a sub-cycle of the larger global carbon cycle. Permafrost is defined as subsurface material that remains below 0o C (32o F) for at least two consecutive years. Because permafrost soils remai ...

. Depending on conditions at the time of thaw, decomposition can release either carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

or methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The abundance of methane on Earth makes ...

, and these greenhouse gas emissions

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from human activities intensify the greenhouse effect. This contributes to climate change. Carbon dioxide (), from burning fossil fuels such as coal, petroleum, oil, and natural gas, is the main cause of climate chan ...

act as a climate change feedback

Climate change feedbacks are natural processes that impact how much global temperatures will increase for a given amount of greenhouse gas emissions. Positive feedbacks amplify global warming while negative feedbacks diminish it.IPCC, 2021Annex ...

. The emissions from thawing permafrost will have a sufficient impact on the climate to impact global carbon budgets. It is difficult to accurately predict how much greenhouse gases the permafrost releases because the different thaw processes are still uncertain. There is widespread agreement that the emissions will be smaller than human-caused emissions and not large enough to result in runaway warming.Fox-Kemper, B.; H. T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S. S. Drijfhout, T. L. Edwards, N. R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R. E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I. S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A. B. A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change

I

Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[Masson-Delmotte, V.; P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, USA, pp. 1211–1362. Instead, the annual permafrost emissions are likely comparable with global emissions from deforestation, or to annual emissions of large countries such as Greenhouse gas emissions by Russia, Russia, the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

or China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

.

Apart from its climate impact, permafrost thaw brings more risks. Formerly frozen ground often contains enough ice that when it thaws, hydraulic saturation is suddenly exceeded, so the ground shifts substantially and may even collapse outright. Many buildings and other infrastructure were built on permafrost when it was frozen and stable, and so are vulnerable to collapse if it thaws. Estimates suggest nearly 70% of such infrastructure is at risk by 2050, and that the associated costs could rise to tens of billions of dollars in the second half of the century. Furthermore, between 13,000 and 20,000 sites contaminated with toxic waste are present in the permafrost, as well as natural mercury deposits, which are all liable to leak and pollute the environment as the warming progresses. Lastly, concerns have been raised about the potential for pathogenic microorganisms surviving the thaw and contributing to future pandemic

A pandemic ( ) is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has a sudden increase in cases and spreads across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. Widespread endemic (epi ...

s. However, this is considered unlikely, and a scientific review on the subject describes the risks as "generally low".

Classification and extent

Permafrost issoil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, water, and organisms that together support the life of plants and soil organisms. Some scientific definitions distinguish dirt from ''soil'' by re ...

, rock or sediment

Sediment is a solid material that is transported to a new location where it is deposited. It occurs naturally and, through the processes of weathering and erosion, is broken down and subsequently sediment transport, transported by the action of ...

that is frozen for more than two consecutive years. In practice, this means that permafrost occurs at a mean annual temperature of or below. In the coldest regions, the depth of continuous permafrost can exceed . It typically exists beneath the so-called active layer, which freezes and thaws annually, and so can support plant growth, as the root

In vascular plants, the roots are the plant organ, organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often bel ...

s can only take hold in the soil that's thawed. Active layer thickness is measured during its maximum extent at the end of summer: as of 2018, the average thickness in the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

is ~, but there are significant regional differences. Northeastern Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

, Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

and Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

have the most solid permafrost with the lowest extent of active layer (less than on average, and sometimes only ), while southern Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

and the Mongolian Plateau are the only areas where the average active layer is deeper than , with the record of . The border between active layer and permafrost itself is sometimes called permafrost table.

Around 15% of Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

land that is not completely covered by ice is directly underlain by permafrost; 22% is defined as part of a permafrost zone or region. This is because only slightly more than half of this area is defined as a continuous permafrost zone, where 90%–100% of the land is underlain by permafrost. Around 20% is instead defined as discontinuous permafrost, where the coverage is between 50% and 90%. Finally, the remaining <30% of permafrost regions consists of areas with 10%–50% coverage, which are defined as sporadic permafrost zones, and some areas that have isolated patches of permafrost covering 10% or less of their area. Most of this area is found in Siberia, northern Canada, Alaska and Greenland. Beneath the active layer annual temperature swings of permafrost become smaller with depth. The greatest depth of permafrost occurs right before the point where geothermal heat maintains a temperature above freezing. Above that bottom limit there may be permafrost with a consistent annual temperature—"isothermal permafrost".

Continuity of coverage

Permafrost typically forms in anyclimate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in a region, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteoro ...

where the mean annual air temperature is lower than the freezing point of water. Exceptions are found in humid boreal forests, such as in Northern Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

and the North-Eastern part of European Russia

European Russia is the western and most populated part of the Russia, Russian Federation. It is geographically situated in Europe, as opposed to the country's sparsely populated and vastly larger eastern part, Siberia, which is situated in Asia ...

west of the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ),; , ; , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range in Eurasia that runs north–south mostly through Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the river Ural (river), Ural and northwestern Kazakhstan.

, where snow acts as an insulating blanket. Glaciated areas may also be exceptions. Since all glaciers are warmed at their base by geothermal heat, temperate glaciers, which are near the pressure melting point throughout, may have liquid water at the interface with the ground and are therefore free of underlying permafrost. "Fossil" cold anomalies in the geothermal gradient

Geothermal gradient is the rate of change in temperature with respect to increasing depth in Earth's interior. As a general rule, the crust temperature rises with depth due to the heat flow from the much hotter mantle; away from tectonic plat ...

in areas where deep permafrost developed during the Pleistocene persist down to several hundred metres. This is evident from temperature measurements in borehole

A borehole is a narrow shaft bored in the ground, either vertically or horizontally. A borehole may be constructed for many different purposes, including the extraction of water ( drilled water well and tube well), other liquids (such as petr ...

s in North America and Europe.

Discontinuous permafrost

The below-ground temperature varies less from season to season than the air temperature, with mean annual temperatures tending to increase with depth due to the geothermal crustal gradient. Thus, if the mean annual air temperature is only slightly below , permafrost will form only in spots that are sheltered (usually with a northern or southern aspect, in the north and south hemispheres respectively) creating discontinuous permafrost. Usually, permafrost will remain discontinuous in a climate where the mean annual soil surface temperature is between . In the moist-wintered areas mentioned before, there may not even be discontinuous permafrost down to . Discontinuous permafrost is often further divided into extensive discontinuous permafrost, where permafrost covers between 50 and 90 percent of the landscape and is usually found in areas with mean annual temperatures between , and sporadic permafrost, where permafrost cover is less than 50 percent of the landscape and typically occurs at mean annual temperatures between .

In soil science, the sporadic permafrost zone is abbreviated SPZ and the extensive discontinuous permafrost zone DPZ. Exceptions occur in un-glaciated

The below-ground temperature varies less from season to season than the air temperature, with mean annual temperatures tending to increase with depth due to the geothermal crustal gradient. Thus, if the mean annual air temperature is only slightly below , permafrost will form only in spots that are sheltered (usually with a northern or southern aspect, in the north and south hemispheres respectively) creating discontinuous permafrost. Usually, permafrost will remain discontinuous in a climate where the mean annual soil surface temperature is between . In the moist-wintered areas mentioned before, there may not even be discontinuous permafrost down to . Discontinuous permafrost is often further divided into extensive discontinuous permafrost, where permafrost covers between 50 and 90 percent of the landscape and is usually found in areas with mean annual temperatures between , and sporadic permafrost, where permafrost cover is less than 50 percent of the landscape and typically occurs at mean annual temperatures between .

In soil science, the sporadic permafrost zone is abbreviated SPZ and the extensive discontinuous permafrost zone DPZ. Exceptions occur in un-glaciated Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

and Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

where the present depth of permafrost is a relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains or personal effects of a saint or other person preserved for the purpose of veneration as a tangible memorial. Reli ...

of climatic conditions during glacial ages where winters were up to colder than those of today.

Continuous permafrost

At mean annual soil surface temperatures below the influence of aspect can never be sufficient to thaw permafrost and a zone of continuous permafrost (abbreviated to CPZ) forms. A line of continuous permafrost in theNorthern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

represents the most southern border where land is covered by continuous permafrost or glacial ice. The line of continuous permafrost varies around the world northward or southward due to regional climatic changes. In the southern hemisphere, most of the equivalent line would fall within the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60th parallel south, 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is the seco ...

if there were land there. Most of the Antarctic continent is overlain by glaciers, under which much of the terrain is subject to basal melting

Melting, or fusion, is a physical process that results in the phase transition of a substance from a solid to a liquid. This occurs when the internal energy of the solid increases, typically by the application of heat or pressure, which inc ...

. The exposed land of Antarctica is substantially underlain with permafrost, some of which is subject to warming and thawing along the coastline.

Alpine permafrost

A range of elevations in both the Northern and Southern Hemisphere are cold enough to support perennially frozen ground: some of the best-known examples include the Canadian Rockies, the European Alps,Himalaya

The Himalayas, or Himalaya ( ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the Earth's highest peaks, including the highest, Mount Everest. More than 100 pea ...

and the Tien Shan

The Tian Shan, also known as the Tengri Tagh or Tengir-Too, meaning the "Mountains of God/Heaven", is a large system of mountain ranges in Central Asia. The highest peak is Jengish Chokusu at high and located in Kyrgyzstan. Its lowest point is ...

. In general, it has been found that extensive alpine permafrost requires mean annual air temperature of , though this can vary depending on local topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the landforms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

, and some mountain areas are known to support permafrost at . It is also possible for subsurface alpine permafrost to be covered by warmer, vegetation-supporting soil.

Alpine permafrost is particularly difficult to study, and systematic research efforts did not begin until the 1970s. Consequently, there remain uncertainties about its geography As recently as 2009, permafrost had been discovered in a new area – Africa's highest peak, Mount Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro () is a dormant volcano in Tanzania. It is the highest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain above sea level in the world, at above sea level and above its plateau base. It is also the highest volcano i ...

( above sea level and approximately 3° south of the equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

). In 2014, a collection of regional estimates of alpine permafrost extent had established a global extent of . However, by 2014, alpine permafrost in the Andes

The Andes ( ), Andes Mountains or Andean Mountain Range (; ) are the List of longest mountain chains on Earth, longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range ...

had not been fully mapped, although its extent has been modeled to assess the amount of water bound up in these areas.

Subsea permafrost

Subsea permafrost occurs beneath the

Subsea permafrost occurs beneath the seabed

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as seabeds.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

and exists in the continental shelves

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

of the polar regions. These areas formed during the last Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages, and g ...

, when a larger portion of Earth's water was bound up in ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacier, glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are the Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet. Ice s ...

s on land and when sea levels were low. As the ice sheets melted to again become seawater during the Holocene glacial retreat, coastal permafrost became submerged shelves under relatively warm and salty boundary conditions, compared to surface permafrost. Since then, these conditions led to the gradual and ongoing decline of subsea permafrost extent. Nevertheless, its presence remains an important consideration for the "design, construction, and operation of coastal facilities, structures founded on the seabed, artificial island

An artificial island or man-made island is an island that has been Construction, constructed by humans rather than formed through natural processes. Other definitions may suggest that artificial islands are lands with the characteristics of hum ...

s, sub-sea pipelines, and wells drilled for exploration

Exploration is the process of exploring, an activity which has some Expectation (epistemic), expectation of Discovery (observation), discovery. Organised exploration is largely a human activity, but exploratory activity is common to most organis ...

and production". Subsea permafrost can also overlay deposits of methane clathrate

Methane clathrate (CH4·5.75H2O) or (4CH4·23H2O), also called methane hydrate, hydromethane, methane ice, fire ice, natural gas hydrate, or gas hydrate, is a solid clathrate compound (more specifically, a clathrate hydrate) in which a large a ...

, which were once speculated to be a major climate tipping point in what was known as a clathrate gun hypothesis

The clathrate gun hypothesis is a proposed explanation for the periods of rapid warming during the Quaternary. The hypothesis is that changes in fluxes in upper intermediate waters in the ocean caused temperature fluctuations that alternately accu ...

, but are now no longer believed to play any role in projected climate change.

Past extent of permafrost

At theLast Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Last Glacial Coldest Period, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period where ice sheets were at their greatest extent between 26,000 and 20,000 years ago.

Ice sheets covered m ...

, continuous permafrost covered a much greater area than it does today, covering all of ice-free Europe south to about Szeged

Szeged ( , ; see also #Etymology, other alternative names) is List of cities and towns of Hungary#Largest cities in Hungary, the third largest city of Hungary, the largest city and regional centre of the Southern Great Plain and the county seat ...

(southeastern Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

) and the Sea of Azov

The Sea of Azov is an inland Continental shelf#Shelf seas, shelf sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, and sometimes regarded as a northern extension of the Black Sea. The sea is bounded by Ru ...

(then dry land) and East Asia south to present-day Changchun

Changchun is the capital and largest city of Jilin, Jilin Province, China, on the Songliao Plain. Changchun is administered as a , comprising seven districts, one county and three county-level cities. At the 2020 census of China, Changchun ha ...

and Abashiri

is a city located in Okhotsk Subprefecture, Hokkaido, Japan.

Abashiri is known as the site of the Abashiri Prison, a Meiji-era facility used for the incarceration of political prisoners. The old prison has been turned into a museum, but the ...

. In North America, only an extremely narrow belt of permafrost existed south of the ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacier, glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are the Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet. Ice s ...

at about the latitude of New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

through southern Iowa

Iowa ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the upper Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west; Wisconsin to the northeast, Ill ...

and northern Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

, but permafrost was more extensive in the drier western regions where it extended to the southern border of Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain states, Mountain West subregions of the Western United States. It borders Montana and Wyoming to the east, Nevada and Utah to the south, and Washington (state), ...

and Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

. In the Southern Hemisphere, there is some evidence for former permafrost from this period in central Otago

Otago (, ; ) is a regions of New Zealand, region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island and administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local go ...

and Argentine

Argentines, Argentinians or Argentineans are people from Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical, or cultural. For most Argentines, several (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their ...

Patagonia

Patagonia () is a geographical region that includes parts of Argentina and Chile at the southern end of South America. The region includes the southern section of the Andes mountain chain with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and glaciers ...

, but was probably discontinuous, and is related to the tundra. Alpine permafrost also occurred in the Drakensberg

The Drakensberg (Zulu language, Zulu: uKhahlamba, Sotho language, Sotho: Maloti, Afrikaans: Drakensberge) is the eastern portion of the Great Escarpment, Southern Africa, Great Escarpment, which encloses the central South Africa#Geography, Sout ...

during glacial maxima above about .

Manifestations

Base depth

Permafrost extends to a base depth where geothermal heat from the Earth and the mean annual temperature at the surface achieve an equilibrium temperature of . This base depth of permafrost can vary wildly – it is less than a meter (3 ft) in the areas where it is shallowest, yet reaches in the northern Lena andYana River

The Yana ( rus, Я́на, p=ˈjanə; ) is a river in Sakha in Russia, located between the Lena to the west and the Indigirka to the east.

Course

It is long, and its drainage basin covers . Including its longest source river, the Sartang, i ...

basins in Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. Calculations indicate that the formation time of permafrost greatly slows past the first several metres. For instance, over half a million years was required to form the deep permafrost underlying Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, a time period extending over several glacial and interglacial cycles of the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

.

Base depth is affected by the underlying geology, and particularly by thermal conductivity

The thermal conductivity of a material is a measure of its ability to heat conduction, conduct heat. It is commonly denoted by k, \lambda, or \kappa and is measured in W·m−1·K−1.

Heat transfer occurs at a lower rate in materials of low ...

, which is lower for permafrost in soil than in bedrock

In geology, bedrock is solid rock that lies under loose material ( regolith) within the crust of Earth or another terrestrial planet.

Definition

Bedrock is the solid rock that underlies looser surface material. An exposed portion of bed ...

. Lower conductivity leaves permafrost less affected by the geothermal gradient

Geothermal gradient is the rate of change in temperature with respect to increasing depth in Earth's interior. As a general rule, the crust temperature rises with depth due to the heat flow from the much hotter mantle; away from tectonic plat ...

, which is the rate of increasing temperature with respect to increasing depth in the Earth's interior. It occurs as the Earth's internal thermal energy

The term "thermal energy" is often used ambiguously in physics and engineering. It can denote several different physical concepts, including:

* Internal energy: The energy contained within a body of matter or radiation, excluding the potential en ...

is generated by radioactive decay

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is conside ...

of unstable isotope

Isotopes are distinct nuclear species (or ''nuclides'') of the same chemical element. They have the same atomic number (number of protons in their Atomic nucleus, nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemica ...

s and flows to the surface by conduction at a rate of ~47 terawatts (TW). Away from tectonic plate boundaries, this is equivalent to an average heat flow of 25–30 °C/km (124–139 °F/mi) near the surface.

Massive ground ice

When the ice content of a permafrost exceeds 250 percent (ice to dry soil by mass) it is classified as massive ice. Massive ice bodies can range in composition, in every conceivable gradation from icy

When the ice content of a permafrost exceeds 250 percent (ice to dry soil by mass) it is classified as massive ice. Massive ice bodies can range in composition, in every conceivable gradation from icy mud

Mud (, or Middle Dutch) is loam, silt or clay mixed with water. Mud is usually formed after rainfall or near water sources. Ancient mud deposits hardened over geological time to form sedimentary rock such as shale or mudstone (generally cal ...

to pure ice. Massive icy beds have a minimum thickness of at least 2 m and a short diameter

In geometry, a diameter of a circle is any straight line segment that passes through the centre of the circle and whose endpoints lie on the circle. It can also be defined as the longest Chord (geometry), chord of the circle. Both definitions a ...

of at least 10 m. First recorded North American observations of this phenomenon were by European scientists at Canning River (Alaska) in 1919. Russian literature provides an earlier date of 1735 and 1739 during the Great North Expedition by P. Lassinius and Khariton Laptev, respectively. Russian investigators including I. A. Lopatin, B. Khegbomov, S. Taber and G. Beskow had also formulated the original theories for ice inclusion in freezing soils.

While there are four categories of ice in permafrost – pore ice, ice wedges (also known as vein ice), buried surface ice and intrasedimental (sometimes also called constitutional) ice – only the last two tend to be large enough to qualify as massive ground ice. These two types usually occur separately, but may be found together, like on the coast of Tuktoyaktuk

Tuktoyaktuk ( ; , ) is an Inuvialuit hamlet near the Mackenzie River delta in the Inuvik Region of the Northwest Territories, Canada, at the northern terminus of the Inuvik–Tuktoyaktuk Highway.Montgomery, Marc"Canada now officially connected ...

in western Arctic Canada

Northern Canada (), colloquially the North or the Territories, is the vast northernmost region of Canada, variously defined by geography and politics. Politically, the term refers to the three territories of Canada: Yukon, Northwest Territories a ...

, where the remains of Laurentide Ice Sheet are located.

Buried surface ice may derive from snow, frozen lake or sea ice

Sea ice arises as seawater freezes. Because ice is less density, dense than water, it floats on the ocean's surface (as does fresh water ice). Sea ice covers about 7% of the Earth's surface and about 12% of the world's oceans. Much of the world' ...

, aufeis (stranded river ice) and even buried glacial ice from the former Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

ice sheets. The latter hold enormous value for paleoglaciological research, yet even as of 2022, the total extent and volume of such buried ancient ice is unknown. Notable sites with known ancient ice deposits include Yenisei River

The Yenisey or Yenisei ( ; , ) is the list of rivers by length, fifth-longest river system in the world, and the largest to drain into the Arctic Ocean.

Rising in Mungaragiyn-gol in Mongolia, it follows a northerly course through Lake Baikal a ...

valley in Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

, Russia as well as Banks and Bylot Island in Canada's Nunavut

Nunavut is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the ''Nunavut Act'' and the Nunavut Land Claims Agr ...

and Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories is a federal Provinces and territories of Canada, territory of Canada. At a land area of approximately and a 2021 census population of 41,070, it is the second-largest and the most populous of Provinces and territorie ...

. Some of the buried ice sheet remnants are known to host thermokarst lakes.

Intrasedimental or constitutional ice has been widely observed and studied across Canada. It forms when subterranean waters freeze in place, and is subdivided into intrusive, injection and segregational ice. The latter is the dominant type, formed after crystallizational differentiation in wet sediment

Sediment is a solid material that is transported to a new location where it is deposited. It occurs naturally and, through the processes of weathering and erosion, is broken down and subsequently sediment transport, transported by the action of ...

s, which occurs when water migrates to the freezing front under the influence of van der Waals force

In molecular physics and chemistry, the van der Waals force (sometimes van der Waals' force) is a distance-dependent interaction between atoms or molecules. Unlike ionic or covalent bonds, these attractions do not result from a chemical elec ...

s. This is a slow process, which primarily occurs in silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension (chemistry), suspension with water. Silt usually ...

s with salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt (chemistry), salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensio ...

less than 20% of seawater

Seawater, or sea water, is water from a sea or ocean. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 35 ppt, 600 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly one liter by volume) of seawater has approximat ...

: silt sediments with higher salinity and clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, ). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impuriti ...

sediments instead have water movement prior to ice formation dominated by rheological processes. Consequently, it takes between 1 and 1000 years to form intrasedimental ice in the top 2.5 meters of clay sediments, yet it takes between 10 and 10,000 years for peat

Peat is an accumulation of partially Decomposition, decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, Moorland, moors, or muskegs. ''Sphagnum'' moss, also called peat moss, is one of the most ...

sediments and between 1,000 and 1,000,000 years for silt sediments.

Landforms

Permafrost processes such as thermal contraction generating cracks which eventually becomeice wedge

An ice wedge is a crack in the ground formed by a narrow or thin piece of ice that measures up to 3–4 meters in length at ground level and extends downwards into the ground up to several meters. During the winter months, the water in the gr ...

s and solifluction

Solifluction is a collective name for gradual processes in which a mass moves down a slope ("mass wasting") related to freeze-thaw activity. This is the standard modern meaning of solifluction, which differs from the original meaning given to i ...

– gradual movement of soil down the slope as it repeatedly freezes and thaws – often lead to the formation of ground polygons, rings, steps and other forms of patterned ground

Patterned ground is the distinct and often symmetrical natural pattern of geometric shapes formed by the deformation of ground material in periglacial regions. It is typically found in remote regions of the Arctic, Antarctica, and the Outback ...

found in arctic, periglacial and alpine areas. In ice-rich permafrost areas, melting of ground ice initiates thermokarst

Thermokarst is a type of terrain characterised by very irregular surfaces of marshy hollows and small hummocks formed when ice-rich permafrost thaws. The land surface type occurs in Arctic areas, and on a smaller scale in mountainous areas such ...

landforms such as thermokarst lakes, thaw slumps, thermal-erosion gullies, and active layer detachments. Notably, unusually deep permafrost in Arctic moorland

Moorland or moor is a type of Habitat (ecology), habitat found in upland (geology), upland areas in temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands and the biomes of montane grasslands and shrublands, characterised by low-growing vegetation on So ...

s and bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and musk ...

s often attracts meltwater in warmer seasons, which pools and freezes to form ice lenses, and the surrounding ground begins to jut outward at a slope. This can eventually result in the formation of large-scale land forms around this core of permafrost, such as palsas – long (), wide () yet shallow (< tall) peat

Peat is an accumulation of partially Decomposition, decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, Moorland, moors, or muskegs. ''Sphagnum'' moss, also called peat moss, is one of the most ...

mound

A mound is a wikt:heaped, heaped pile of soil, earth, gravel, sand, rock (geology), rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded ...

s – and the even larger pingos, which can be high and in diameter

In geometry, a diameter of a circle is any straight line segment that passes through the centre of the circle and whose endpoints lie on the circle. It can also be defined as the longest Chord (geometry), chord of the circle. Both definitions a ...

.

Tuktoyaktuk

Tuktoyaktuk ( ; , ) is an Inuvialuit hamlet near the Mackenzie River delta in the Inuvik Region of the Northwest Territories, Canada, at the northern terminus of the Inuvik–Tuktoyaktuk Highway.Montgomery, Marc"Canada now officially connected ...

, Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories is a federal Provinces and territories of Canada, territory of Canada. At a land area of approximately and a 2021 census population of 41,070, it is the second-largest and the most populous of Provinces and territorie ...

, Canada

File:Permafrost - polygon.jpg, Ground polygons

File:Permafrost stone-rings hg.jpg, Stone rings on Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian language, Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipel ...

File:Polygons in Padjelanta.jpg, Helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which Lift (force), lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning Helicopter rotor, rotors. This allows the helicopter to VTOL, take off and land vertically, to hover (helicopter), hover, and ...