Constitutional status of Cornwall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The constitutional status of Cornwall has been a matter of debate and dispute.

The constitutional status of Cornwall has been a matter of debate and dispute.

In pre-Roman times, Cornwall was part of the kingdom of

In pre-Roman times, Cornwall was part of the kingdom of

''The Saints of Cornwall''

Oxford University Press (2000) , pp. 9–10 The '' Bodmin manumissions'', two to three generations later, show that the ruling class of Cornwall quickly became "Anglicised", most owners of slaves having Anglo-Saxon names (not necessarily because they were of English descent; some at least were Cornish nobles who changed their names). It is clear that at this time areas beyond the core of Anglo-Saxon settlement were recognised as different by the English kings. Athelstan's successor, Edmund, in a charter for an estate just north of Exeter, styled himself as "King of the English, and ruler of this province of Britons". Edmund's successor Edgar styled himself "King of the English and ruler of the adjacent nations". Surviving charters issued by the Kings of England

Additionally, Cornwall was also divided into " Hundreds", which often bore the name of "shire" in English. In Cornish, they were called (sing. ).

Although the name "shire", today implies some kind of county status, hundreds in some English counties often bore the suffix 'shire' as well (e.g., Salfordshire), but where English shires were split into hundreds each having their own constable, Cornish hundreds had constables at parish level.

The were not, however, English hundreds: ''Triggshire'' came from Tricori 'three warbands', suggesting a military muster area capable of supporting three hundred fighting men. However it must be said that this is an inference from name alone, and does not constitute historical evidence of any fighting force raised by a Cornish hundred.

The Cornish replicated England's shire system on a smaller scale. Although by the 15th century the shires of Cornwall had become hundreds, the administrative differences remained in place long after.

Additionally, Cornwall was also divided into " Hundreds", which often bore the name of "shire" in English. In Cornish, they were called (sing. ).

Although the name "shire", today implies some kind of county status, hundreds in some English counties often bore the suffix 'shire' as well (e.g., Salfordshire), but where English shires were split into hundreds each having their own constable, Cornish hundreds had constables at parish level.

The were not, however, English hundreds: ''Triggshire'' came from Tricori 'three warbands', suggesting a military muster area capable of supporting three hundred fighting men. However it must be said that this is an inference from name alone, and does not constitute historical evidence of any fighting force raised by a Cornish hundred.

The Cornish replicated England's shire system on a smaller scale. Although by the 15th century the shires of Cornwall had become hundreds, the administrative differences remained in place long after.

Some people reject all claims that Cornwall is, or ought to be, distinct from England. While recognising that there are local peculiarisms, they point out that

Some people reject all claims that Cornwall is, or ought to be, distinct from England. While recognising that there are local peculiarisms, they point out that

The Kilbrandon Report (1969–1971) into the British constitution recommends that, when referring to

The Kilbrandon Report (1969–1971) into the British constitution recommends that, when referring to

The Cornish Stannary ParliamentMaps of Cornwall

on

The Cornish Assembly – Senedh Kernow The Cornish: A Neglected Nation?

{{DEFAULTSORT:Constitutional Status of Cornwall Politics of Cornwall Home rule in the United Kingdom Constitution of the United Kingdom Politics of the United Kingdom Government of the United Kingdom Law of the United Kingdom Cornish nationalism Legal history of the United Kingdom

Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

is an administrative county

An administrative county was a first-level administrative division in England and Wales from 1888 to 1974, and in Ireland from 1899 until 1973 in Northern Ireland, 2002 in the Republic of Ireland. They are now abolished, although most Northern ...

of England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

.

In ethnic and cultural terms, until around 1700, Cornwall and its inhabitants were regarded as a separate people by their English neighbours. One aspect of the distinct identity of Cornwall is the Cornish language

Cornish (Standard Written Form: or , ) is a Southwestern Brittonic language, Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. Along with Welsh language, Welsh and Breton language, Breton, Cornish descends from Common Brittonic, ...

, which survived into the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

and has been revived in the modern era

The modern era or the modern period is considered the current historical period of human history. It was originally applied to the history of Europe and Western history for events that came after the Middle Ages, often from around the year 1500 ...

.

History

Prior to the Norman Conquest

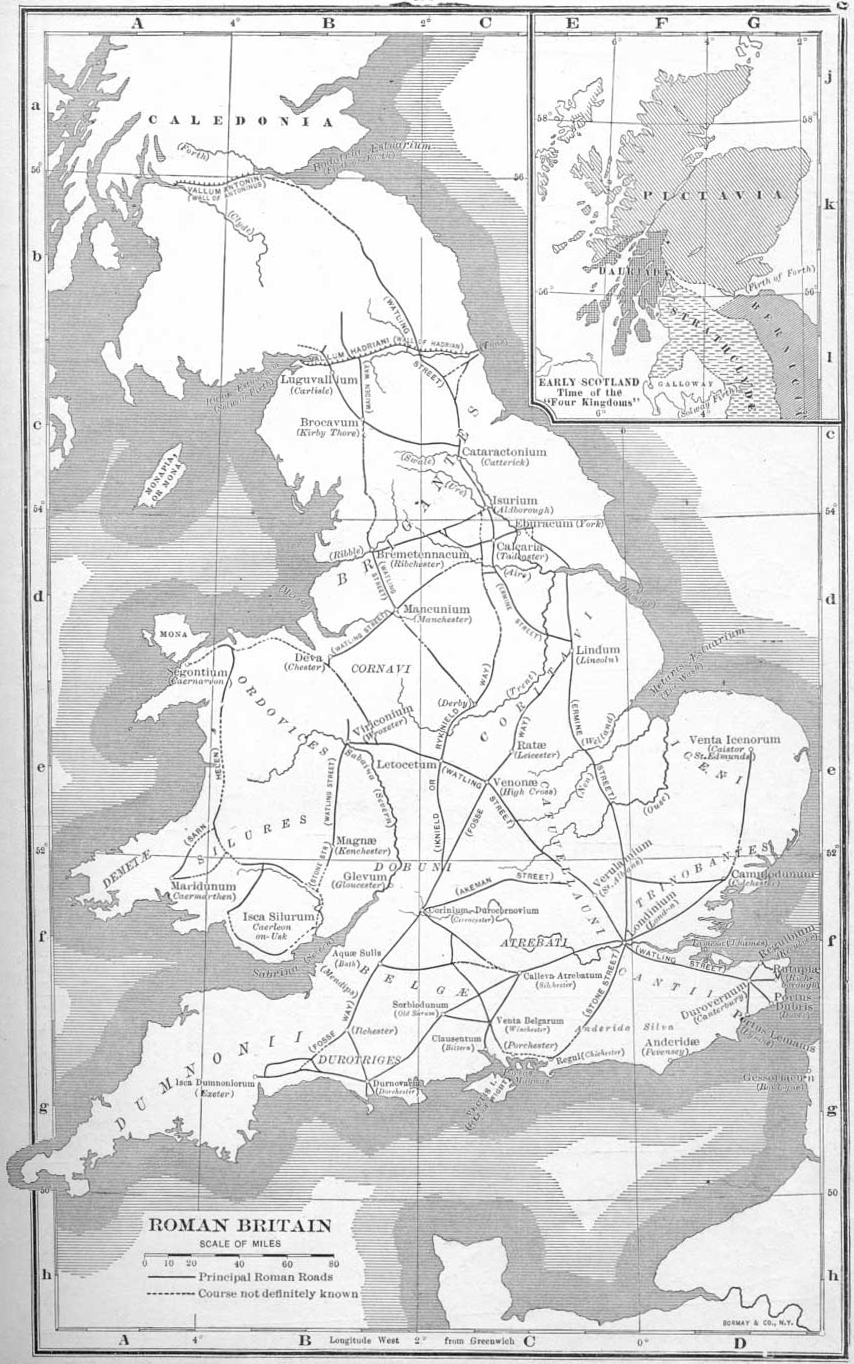

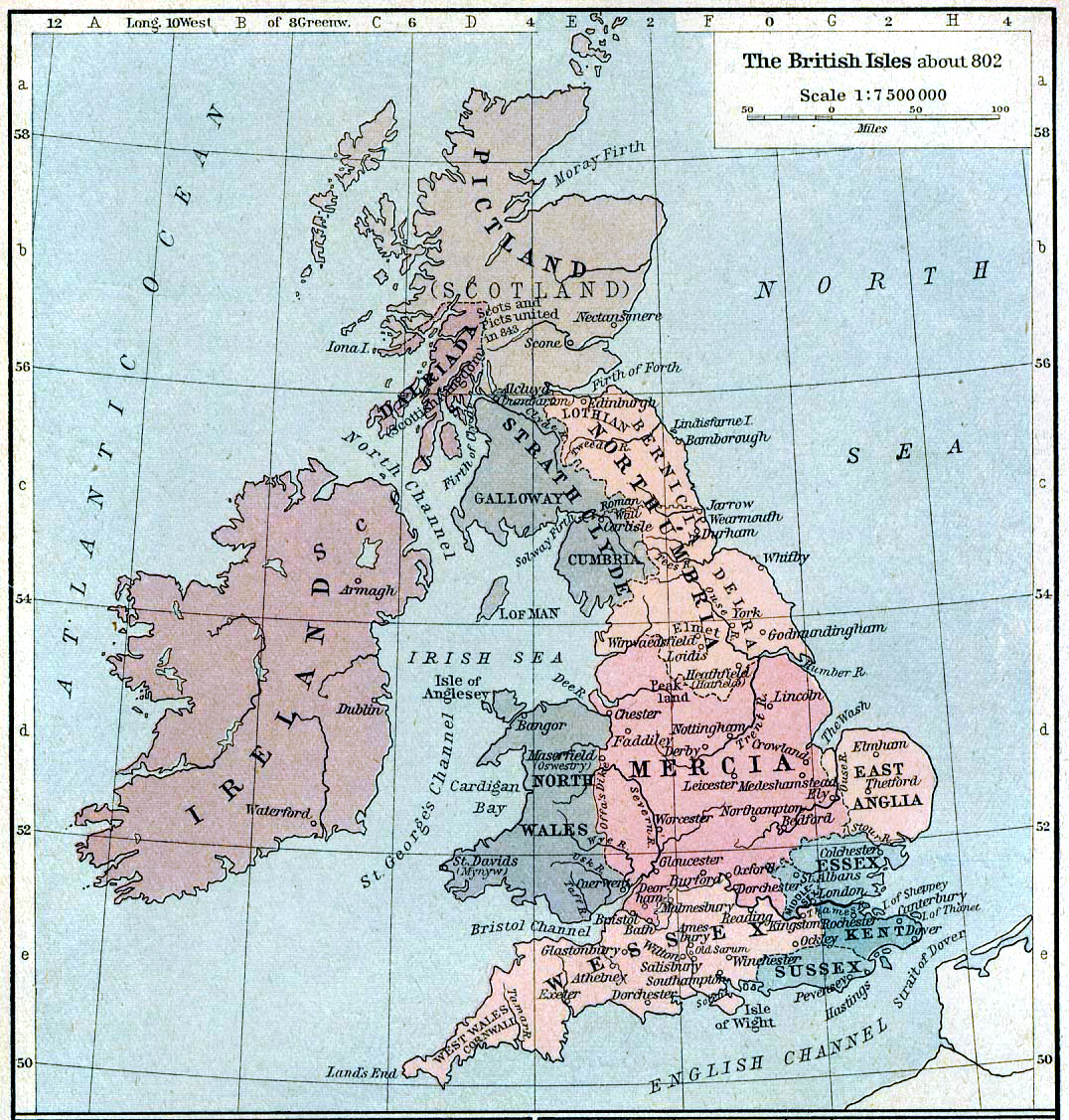

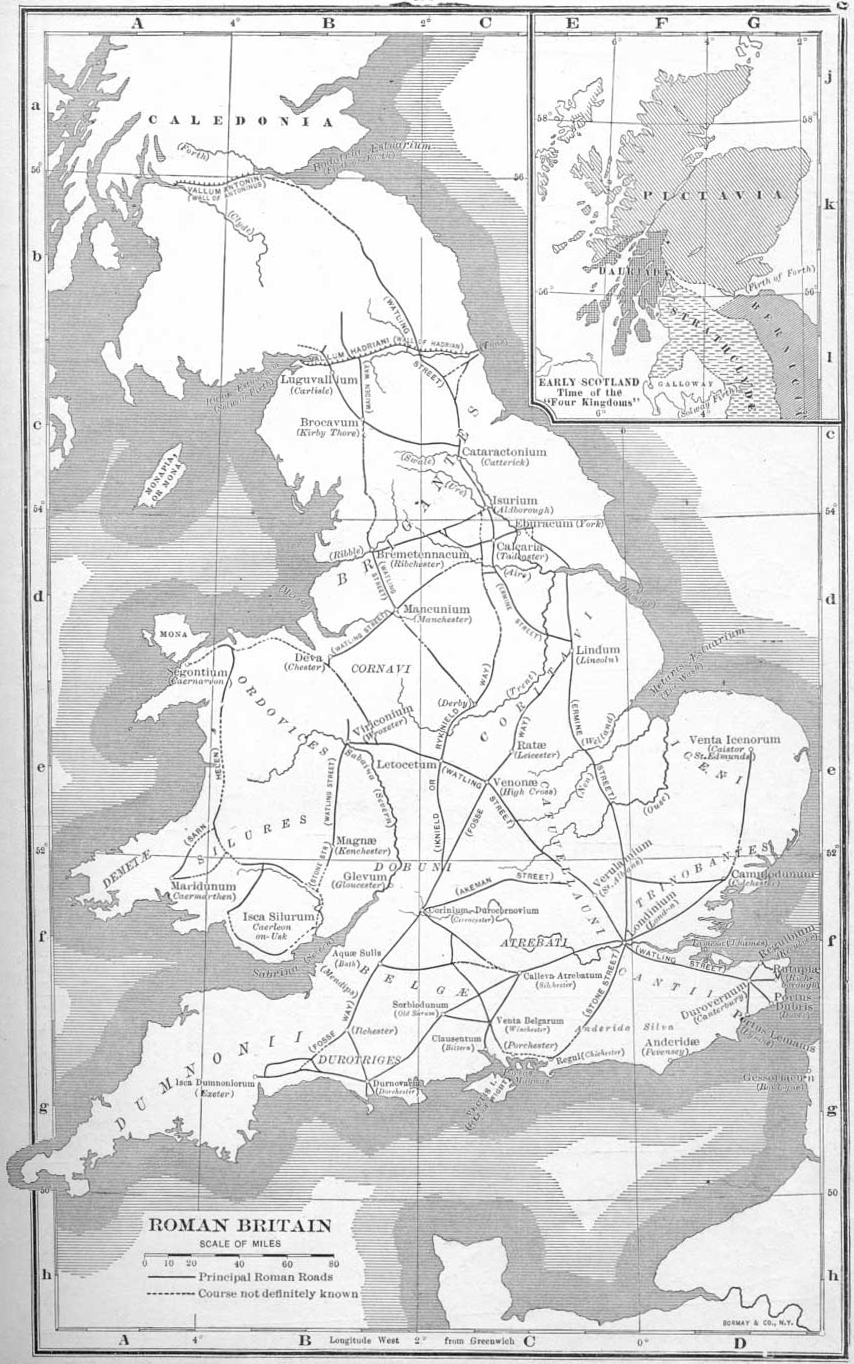

In pre-Roman times, Cornwall was part of the kingdom of

In pre-Roman times, Cornwall was part of the kingdom of Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for a Brythonic kingdom that existed in Sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries CE in the more westerly parts of present-day South West England. It was centred in the area of modern Devon, ...

. Later, it was known to the Anglo-Saxons as ''West Wales'', to distinguish it from North Wales, that is, modern-day Wales. The name ''Cornwall'' is a combination of two elements. The second derives from the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

word '' wealh'', meaning "foreigner" "Celt", "Roman", "Briton", which also survives in the words ''Wales'' and ''Welsh''. The first element "Corn", indicating the shape of the peninsula, is descended from Celtic ''kernou'', an Indo-European word related to English ''horn'' and Latin ''cornu''.

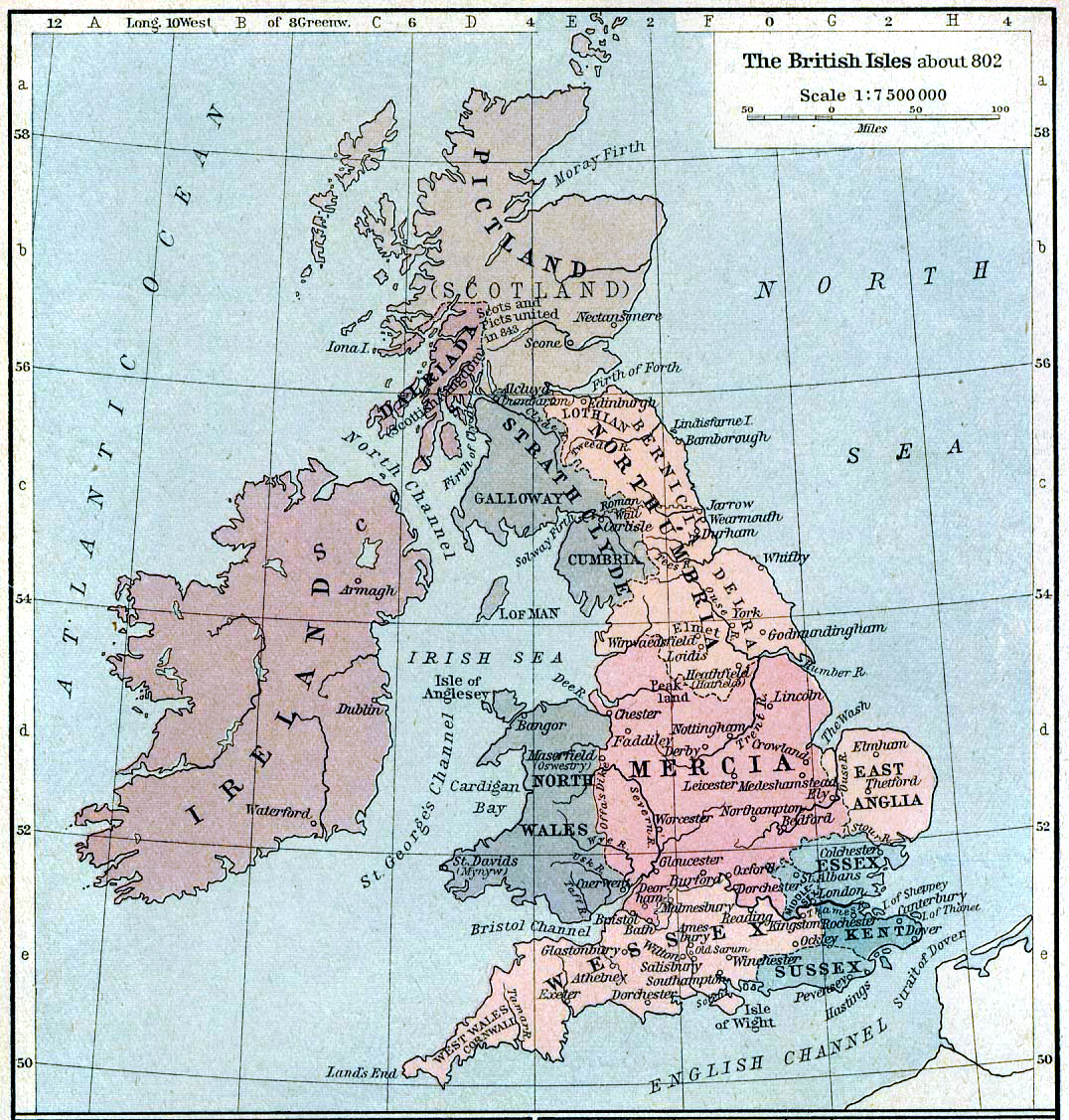

References in contemporary charters (for which there is either an original manuscript or an early copy regarded as authentic) show Egbert of Wessex

Ecgberht (died 839), also spelled Egbert, Ecgbert, Ecgbriht, Ecgbeorht, and Ecbert, was King of Wessex from 802 until his death in 839. His father was King Ealhmund of Kent. In the 780s, Ecgberht was forced into exile to Charlemagne's court i ...

(802–839) granting lands in Cornwall at Kilkhampton, ''Ros'', Maker, Pawton (in St Breock, not far from Wadebridge, head manor of Pydar in Domesday Book), ''Caellwic'' (perhaps Celliwig or Kellywick in Egloshayle), and Lawhitton to Sherborne

Sherborne is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in north west Dorset, in South West England. It is sited on the River Yeo (South Somerset), River Yeo, on the edge of the Blackmore Vale, east of Yeovil. The parish include ...

Abbey and to the Bishop of Sherborne. All of the identifiable locations except Pawton are in the far east of Cornwall, so these references show a degree of West Saxon control over its eastern fringes. Such control had certainly been established in places by the later ninth century, as indicated by the will of King Alfred the Great (871–899).

King Athelstan, who came to the throne of England in 924 CE, immediately began a campaign to consolidate his power, and by about 926 had taken control of the Kingdom of Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

, following which he established firm boundaries with other kingdoms such as Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

and Cornwall. The latter agreement, according to 12th century West Country

The West Country is a loosely defined area within southwest England, usually taken to include the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset and Bristol, with some considering it to extend to all or parts of Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and ...

historian William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury (; ) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as "a gifted historical scholar and a ...

, ended rights of residence for Cornish subjects in Exeter

Exeter ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and the county town of Devon in South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter w ...

, and fixed the Cornish boundary at the east bank of the River Tamar

The Tamar (; ) is a river in south west England that forms most of the border between Devon (to the east) and Cornwall (to the west). A large part of the valley of the Tamar is protected as the Tamar Valley National Landscape (an Area of Outsta ...

. At Easter 928, Athelstan held court at Exeter, with the Welsh and "West Welsh" subject rulers present, and by 931 he had appointed a bishop for Cornwall within the English church (i.e. subject to the authority of the Archbishop of Canterbury).Orme, Nicholas''The Saints of Cornwall''

Oxford University Press (2000) , pp. 9–10 The '' Bodmin manumissions'', two to three generations later, show that the ruling class of Cornwall quickly became "Anglicised", most owners of slaves having Anglo-Saxon names (not necessarily because they were of English descent; some at least were Cornish nobles who changed their names). It is clear that at this time areas beyond the core of Anglo-Saxon settlement were recognised as different by the English kings. Athelstan's successor, Edmund, in a charter for an estate just north of Exeter, styled himself as "King of the English, and ruler of this province of Britons". Edmund's successor Edgar styled himself "King of the English and ruler of the adjacent nations". Surviving charters issued by the Kings of England

Edmund I

Edmund I or Eadmund I (920/921 – 26 May 946) was King of the English from 27 October 939 until his death in 946. He was the elder son of King Edward the Elder and his third wife, Queen Eadgifu, and a grandson of King Alfred the Great. Af ...

(939–946), Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used masculine English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Edgar'' (composed of ''wikt:en:ead, ead'' "rich, prosperous" and ''Gar (spear), gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the Late Midd ...

(959–975), Edward the Martyr (975–978), Aethelred II (978–1016), Edmund II (1016), Cnut

Cnut ( ; ; – 12 November 1035), also known as Canute and with the epithet the Great, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norway from 1028 until his death in 1035. The three kingdoms united under Cnut's rul ...

(1016–1035) and Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was King of England from 1042 until his death in 1066. He was the last reigning monarch of the House of Wessex.

Edward was the son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy. He succeede ...

(1042–1066) record grants of land in Cornwall made by these kings. In contrast to the easterly concentration of the estates held or granted by English kings in the ninth century, the tenth and eleventh-century grants were widely distributed across Cornwall. As is usual with charters of this period, the authenticity of some of these documents is open to question (though Della Hooke has established high reliability for the Cornish material), but that of others (e.g., Edgar's grant of estates at Tywarnhaile and ''Bosowsa'' to his thane

Thane (; previously known as Thana, List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1996) is a metropolitan city located on the northwestern side of the list of Indian states, state of Maharashtra in India and on ...

Eanulf in 960, Edward the Confessor's grant of estates at Traboe, Trevallack, Grugwith and Trethewey to Bishop Ealdred in 1059) is not in any doubt. Some of these grants include exemptions from obligations to the crown which would otherwise accompany land ownership, while retaining others, including those regarding military service. Assuming that these documents are authentic, the attachment of these obligations to the King of England to ownership of land in Cornwall suggests that the area was under his direct rule and implies that the legal and administrative relationship between the king and his subjects was the same there as elsewhere in his kingdom.

In 1051, with the exile of Godwin, Earl of Wessex

Godwin of Wessex (; died 15 April 1053) was an Anglo-Saxon nobleman who became one of the most powerful earls in England under the Danish king Cnut the Great (King of England from 1016 to 1035) and his successors. Cnut made Godwin the first ...

and his sons and the forfeiture of their earldoms, a man named Odda

Odda () is a list of former municipalities of Norway, former municipality in the old Hordaland counties of Norway, county, Norway. The municipality existed from 1913 until its dissolution in 2020 when it was merged into Ullensvang Municipality i ...

was appointed earl over a portion of the lands thus vacated: this comprised Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

, Somerset, Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

, and "Wealas".Swanton, Michael (tr.) (2000). ''The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles'', 2nd ed., London, Phoenix Press; p. 177 As ''Wealas'' is Saxon for foreigners, this could mean "West Wales"—that is, Cornwall—or it could mean that he was overlord of the Cornish foreigners in Devon or elsewhere.

Elizabethan historian William Camden

William Camden (2 May 1551 – 9 November 1623) was an English antiquarian, historian, topographer, and herald, best known as author of ''Britannia'', the first chorographical survey of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland that relates la ...

, in the Cornish section of his ''Britannia'', notes that:

As for the Earles, none of British bloud are mentioned but onely Candorus (called by others Cadocus), who is accounted by the late writers the last Earle of Cornwall of British race.

Norman conquest and after

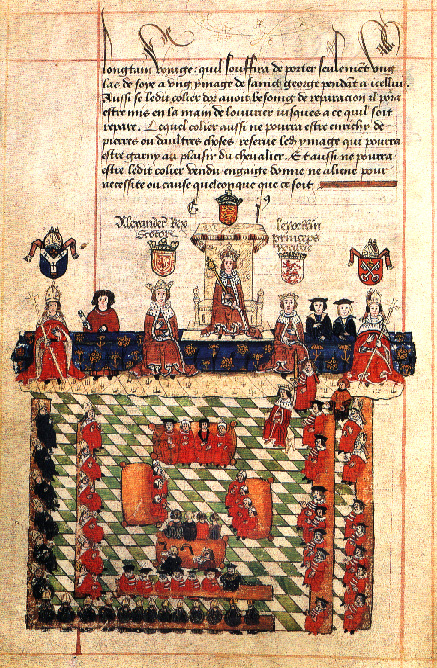

Cornwall was included in the survey, initiated byWilliam the Conqueror

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was D ...

, the first Norman king of England, which became known as the ''Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

'', where it is included as being part of the Norman king's new domain. Cornwall was unusual as Domesday records no Saxon ''burh

A burh () or burg was an Anglo-Saxon fortification or fortified settlement. In the 9th century, raids and invasions by Vikings prompted Alfred the Great to develop a network of burhs and roads to use against such attackers. Some were new constru ...

''; a ''burh'' (borough) was the Saxons' centre of legal and administrative power. Moreover, nearly all land was held by one person, William's half-brother Robert of Mortain

Robert, Count of Mortain, first Earl of Cornwall of 2nd creation (–) was a Norman nobleman and the half-brother (on their mother's side) of King William the Conqueror. He was one of the very few proven companions of William the Conqueror at t ...

, who may have been the first Norman to bear the title Earl of Cornwall

The title of Earl of Cornwall was created several times in the Peerage of England before 1337, when it was superseded by the title Duke of Cornwall, which became attached to heirs-apparent to the throne.

Condor of Cornwall

*Condor of Cornwall, ...

. He held his Cornish lands not as a Tenant in Chief of the King, as was the case with other landowners, but as de facto viceroy.

F. M. Stenton tells us that the early Norman compilation known as "The Laws of William the Conqueror" records all regions under West Saxon law. These included Kent, Surrey, Sussex, Berkshire, Hampshire, Wiltshire, Dorset, Somerset and Devon. Cornwall is not recorded as being under West Saxon, or English, law.

Ingulf was secretary to William the Conqueror and after 1066 was appointed Abbot of Croyland. When his church burned down, he established a fund raising committee to rebuild it. Ingulf's Chronicle tells us:

Henry of Huntingdon

Henry of Huntingdon (; 1088 – 1157), the son of a canon in the diocese of Lincoln, was a 12th-century English historian and the author of ''Historia Anglorum'' (Medieval Latin for "History of the English"), as "the most important Anglo- ...

, writing about 1129, included Cornwall in his list of shires of England in his ''History of the English''.

The '' Scrope v Grosvenor'' lawsuit of 1386–1389 upheld the rule that two claimants of the same nation may not bear the same arms

Arms or ARMS may refer to:

*Arm or arms, the upper limbs of the body

Arm, Arms, or ARMS may also refer to:

People

* Ida A. T. Arms (1856–1931), American missionary-educator, temperance leader

Coat of arms or weapons

*Armaments or weapons

**Fi ...

. However, the same case allowed Thomas Carminow of Cornwall to continue to do so, as Cornwall was considered a separate country, being "a large land formerly bearing the name of a kingdom".

The phrase "England and Cornwall" () has been used on occasion in post-Norman official documents referring to the Duchy of Cornwall:

Tudor period

The ItalianPolydore Vergil

Polydore Vergil or Virgil (Italian: Polidoro Virgili, commonly Latinised as Polydorus Vergilius; – 18 April 1555), widely known as Polydore Vergil of Urbino, was an Italian humanist scholar, historian, priest and diplomat, who spent much of ...

in his ''Anglica Historia'', published in 1535 wrote that four peoples speaking four different languages inhabited Britain:

During the Tudor period some travellers regarded the Cornish as a separate cultural group, from which some modern observers conclude that they were a separate ethnic group. For example, Lodovico Falier, an Italian diplomat at the court of Henry VIII said, "The language of the English, Welsh and Cornish men is so different that they do not understand each other." He went on to give the alleged 'national characteristics' of the three peoples, saying for example "the Cornishman is poor, rough and boorish".

Another example is Gaspard de Coligny Châtillon – the French Ambassador in London – who wrote saying that England was not a united whole as it "contains Wales and Cornwall, natural enemies of the rest of England, and speaking a different language". His use of the phrase "the rest of" implies that he believed Cornwall and Wales to be part of England in his sense of the word.

Some maps of the British Isles prior to the 17th century showed Cornwall (Cornubia/Cornwallia) as a territory on a par with Wales. However most post-date the incorporation of Wales as a principality of England. Examples include the maps of Sebastian Munster (1515), Abraham Ortelius

Abraham Ortelius (; also Ortels, Orthellius, Wortels; 4 or 14 April 152728 June 1598) was a cartographer, geographer, and cosmographer from Antwerp in the Spanish Netherlands. He is recognized as the creator of the list of atlases, first modern ...

, and Girolamo Ruscelli. Maps that depict Cornwall as a county of the Kingdom of England and Wales include

Gerardus Mercator

Gerardus Mercator (; 5 March 1512 – 2 December 1594) was a Flemish people, Flemish geographer, cosmographer and Cartography, cartographer. He is most renowned for creating the Mercator 1569 world map, 1569 world map based on a new Mercator pr ...

's 1564 atlas of Europe, and Christopher Saxton

Christopher Saxton (c. 1540 – c. 1610) was an English cartographer who produced the first county maps of England and Wales.

Life and family

Saxton was probably born in Sowood, Ossett in the parish of Dewsbury, in the West Riding of Yorkshire ...

's 1579 map authorised by Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

.

A miniature "epitome" of Ortelius' map of England and Wales, published in 1595, names Cornwall; the same map displays Kent in an equivalent manner. Maps of Britain which display Cornwall usually in their legends do not refer to Cornwall, e.g. Lily 1548.

17th and 18th centuries

Recognition that several peoples lived within Britain and Ireland continued through the 17th century. For example, after the death ofElizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

in 1603, the Venetian ambassador wrote that the late queen had ruled over five different 'peoples': "English, Welsh, Cornish, Scottish ... and Irish".

Writing in 1616, diplomat Arthur Hopton stated:

England is... divided into 3 great Provinces, or Countries... every of them speaking a several and different language, as English, Welsh and Cornish.Wales was effectively annexed to the

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from the late 9th century, when it was unified from various Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland to f ...

in the 16th century by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542, but references to 'England' in law were not presumed to include Wales (or indeed Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census recor ...

) until the Wales and Berwick Act 1746

The Wales and Berwick Act 1746 (20 Geo. 2. c. 42) was an Act of Parliament, act of the Parliament of Great Britain that created a statutory definition of England as including England, Wales and Berwick-upon-Tweed.

The walled garrison town of Be ...

. By this time the use of "England and Cornwall" (''Anglia et Cornubia'') had ceased.

Because of the tendency of historians to trust the work of their predecessors, Geoffrey of Monmouth's semi-fictional 12th-century ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' remained influential for centuries, often used by writers who were unaware that his work was the source. For example, in 1769 the antiquary William Borlase wrote the following, which is actually a summary of a passage from Geoffrey ook iii:1

Of this time we are to understand what Edward I. says (Sheringham. 'De Anglorum Gentis Origine''p. 129.) that Britain, Wales, and Cornwall, were the portion ofAnother 18th-century writer, Richard Gough, concentrated on a contemporary viewpoint, noting that "Cornwall seems to be another Kingdom", in his "Camden's Britannia", 2nd ed. (4 vols; London, 1806). During the 18th century,Belinus Belinus was a legendary king of the Britons (historic), Britons, as recounted by Geoffrey of Monmouth. He was the son of Dunvallo Molmutius and brother of Brennius and came to power in 390 BC. He was probably named after the ancient god Belenus. ..., elder son of Dunwallo, and that that part of the Island, afterwards called England, was divided in three shares, viz. Britain, which reached from theTweed Tweed is a rough, woollen fabric, of a soft, open, flexible texture, resembling cheviot or homespun, but more closely woven. It is usually woven with a plain weave, twill or herringbone structure. Colour effects in the yarn may be obtained ..., Westward, as far as the river Ex; Wales inclosed by the riversSevern The River Severn (, ), at long, is the longest river in Great Britain. It is also the river with the most voluminous flow of water by far in all of England and Wales, with an average flow rate of at Apperley, Gloucestershire. It rises in t ..., and Dee; and Cornwall from the river Ex to the Land's-End.

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson ( – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

created an ironic Cornish declaration of independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

that he used in his essay ''Taxation no Tyranny'' His irony starts:

19th century

Popular Cornish sentiment during the 19th century appears to have been still strong. For example, A. K. Hamilton Jenkin records the reaction of a school pupil who was asked to describe Cornwall's situation replied: "he's kidged to a furren country from the top hand" – i.e., "it's joined to a foreign country from the upper part". This reply was "heard by the whole school with ''much approval'', including old Peggy (the school-dame) herself." The famous crime writerWilkie Collins

William Wilkie Collins (8 January 1824 – 23 September 1889) was an English novelist and playwright known especially for ''The Woman in White (novel), The Woman in White'' (1860), a mystery novel and early sensation novel, and for ''The Moonsto ...

described Cornwall as:

''Chambers' Journal'' in 1861 described Cornwall as "one of the most un-English of English counties" – a sentiment echoed by the naturalist W. H. Hudson who also referred to it as "un-English" and said there were

Until the Tin Duties Abolition Act 1838, the Cornish miner was charged twice the level of taxation compared to the English miner. The English practice of charging 'foreigners' double taxation had existed in Cornwall for over 600 years prior to the 1838 act and was first referenced in William de Wrotham's letter of 1198 AD, published in G. R. Lewis, ''The Stannaries'' 908 The campaigning ''West Briton'' newspaper called the racially applied tax "oppresive and vexatious" (19 January 1838). In 1856 the Westminster Parliament was still able to refer to the Cornish as ''aboriginals'' (Foreshore Case papers, Page 11, Section 25).

Cornish "shires"

Additionally, Cornwall was also divided into " Hundreds", which often bore the name of "shire" in English. In Cornish, they were called (sing. ).

Although the name "shire", today implies some kind of county status, hundreds in some English counties often bore the suffix 'shire' as well (e.g., Salfordshire), but where English shires were split into hundreds each having their own constable, Cornish hundreds had constables at parish level.

The were not, however, English hundreds: ''Triggshire'' came from Tricori 'three warbands', suggesting a military muster area capable of supporting three hundred fighting men. However it must be said that this is an inference from name alone, and does not constitute historical evidence of any fighting force raised by a Cornish hundred.

The Cornish replicated England's shire system on a smaller scale. Although by the 15th century the shires of Cornwall had become hundreds, the administrative differences remained in place long after.

Additionally, Cornwall was also divided into " Hundreds", which often bore the name of "shire" in English. In Cornish, they were called (sing. ).

Although the name "shire", today implies some kind of county status, hundreds in some English counties often bore the suffix 'shire' as well (e.g., Salfordshire), but where English shires were split into hundreds each having their own constable, Cornish hundreds had constables at parish level.

The were not, however, English hundreds: ''Triggshire'' came from Tricori 'three warbands', suggesting a military muster area capable of supporting three hundred fighting men. However it must be said that this is an inference from name alone, and does not constitute historical evidence of any fighting force raised by a Cornish hundred.

The Cornish replicated England's shire system on a smaller scale. Although by the 15th century the shires of Cornwall had become hundreds, the administrative differences remained in place long after.

Constitutional status – arguments on each side

The argument for non-English constitutional status

In 1328 the Earldom of Cornwall, extinct since the disgrace and execution ofPiers Gaveston

Piers Gaveston, 1st Earl of Cornwall ( – 19 June 1312) was an English nobleman of Gascon origin, and the favourite of Edward II of England.

At a young age, Gaveston made a good impression on King Edward I, who assigned him to the househo ...

in 1312, was recreated and awarded to John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

, younger brother of King Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

.

The constitution of the now-defunct ''Council for Racial Equality in Cornwall'' defined Cornwall as follows:

On 14 July 2009, Dan Rogerson

Daniel John Rogerson (born 23 July 1975 in St Austell) is a Cornish Liberal Democrat politician. He was the Member of Parliament (MP) for North Cornwall from the 2005 general election until his defeat at the 2015 general election. In October ...

MP, of the Liberal Democrats, presented a Cornish 'breakaway' bill to the Parliament in Westminster – The Government of Cornwall Bill. The bill proposed a devolved assembly for Cornwall, similar to the Welsh and Scottish setup. The bill states that Cornwall should re-assert its rightful place within the United Kingdom. Rogerson argued that:

The argument for English county status

Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

, Kent, and Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Merseyside to the north-west, Greater Manchester to the north-east, Derbyshire to the east, Staffordshire to the south-east, and Shrop ...

(for example) also have local customs and identities that do not seem to undermine their essential Englishness. The legal claims concerning the Duchy, they argue, are without merit except as relics of mediaeval feudalism, and they contend that Stannary law applied not to Cornwall as a 'nation', but merely to the guild of tin miners. Rather, they argue that Cornwall has been not only in English possession, but part of England itself, either since Athelstan conquered it in 936, since the administrative centralisation of the Tudor dynasty

The House of Tudor ( ) was an English and Welsh dynasty that held the throne of England from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd, a Welsh noble family, and Catherine of Valois. The Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of Eng ...

, or since the creation of Cornwall County Council in 1888. Finally, they agree with representatives of the Duchy

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a country, territory, fiefdom, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or Queen regnant, queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important differe ...

itself that the Duchy is, in essence, a real estate company that serves to raise income for the Prince of Wales. They compare the situation of the Duchy of Cornwall with that of the Duchy of Lancaster, which has similar rights in Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated ''Lancs'') is a ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Cumbria to the north, North Yorkshire and West Yorkshire to the east, Greater Manchester and Merseyside to the south, and the Irish Sea to ...

, which is indisputably part of England. The proponents of such perspectives include not only Unionists, but most branches and agencies of government.

Below are some indications that would tend to support the assertion that for more than the last thousand years Cornwall has been governed as a part of England and in a way indistinguishable from other parts of England:

Governmental positions in the 20th and 21st centuries

Along with other English counties, Cornwall was established as anadministrative county

An administrative county was a first-level administrative division in England and Wales from 1888 to 1974, and in Ireland from 1899 until 1973 in Northern Ireland, 2002 in the Republic of Ireland. They are now abolished, although most Northern ...

under the changes introduced in the Local Government Act 1888

The Local Government Act 1888 (51 & 52 Vict. c. 41) was an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which established county councils and county borough councils in England and Wales. It came into effect ...

, which came into effect on 1 April 1889. This was replaced by a non-metropolitan county

A non-metropolitan county, or colloquially, shire county, is a subdivision of England used for local government.

The non-metropolitan counties were originally created in 1974 as part of a reform of local government in England and Wales, and ...

of Cornwall in 1974 by the Local Government Act 1972

The Local Government Act 1972 (c. 70) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in England and Wales on 1 April 1974. It was one of the most significant acts of Parliament to be passed by the Heath Gov ...

, which includes it under the heading of "England".

In 2008, the government said it would not be undertaking a review of the constitutional status of Cornwall and would not be changing the status of the county. The Justice Minister, Michael Wills, replying to a question from Andrew George MP, stated that "Cornwall is an administrative county of England, electing MPs to the UK Parliament, and is subject to UK legislation. It has always been an integral part of the Union. The Government have no plans to alter the constitutional status of Cornwall." On 26 July 2007, David Cameron appointed Mark Prisk as Shadow Minister for Cornwall, although there was no formal government post for him to shadow. This would bring Cornwall into line with Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

, all of whom have their own respective ministerial level departments. The post and associated department was not made official when the Conservative party went into government with the Liberal Democrats in 2010 however.

In 2015, Cornwall was granted a devolution deal

The Cities and Local Government Devolution Act 2016 (c. 1) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that allows for the introduction of directly elected mayors to combined authorities in England and Wales and the devolution of housing, ...

, the first of its kind given to a council authority. It was criticised by devolution campaigners and nationalists for not ceding enough powers to Cornwall – Mebyon Kernow

Mebyon Kernow – The Party for Cornwall (, MK; Cornish language, Cornish for ''Sons of Cornwall'') is a Cornish nationalism, Cornish nationalist, Left-wing politics, centre-left political party in Cornwall, in southwestern Britain. It currentl ...

leader Dick Cole argued Cornwall should be given devolution powers like those of Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

or Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

.

Moves for recognition of legal autonomy

The Duchy of Cornwall

The Kilbrandon Report (1969–1971) into the British constitution recommends that, when referring to

The Kilbrandon Report (1969–1971) into the British constitution recommends that, when referring to Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

, official sources should "on all appropriate occasions" use the designation of ''duchy'' when referring to Cornwall itself, in recognition of its "special relationship" with the Crown.

In 1780 Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

sought to curtail further the power of the Crown by removing the various principalities which he said existed as different aspects of the monarchy within the country:

The arbitration, as instructed by the Crown, was based on legal argument and documentation, and led to the Cornwall Submarine Mines Act 1858. The officers of the duchy, based on its researches, made this submission:

# That Cornwall, like Wales, was at the time of the Conquest, and was subsequently treated in many respects as distinct from England. # That it was held by the Earls of Cornwall with the rights and prerogative of a County Palatine, as far as regarded the Seignory or territorial dominion. # That the Dukes of Cornwall have from the creation of the Duchy enjoyed the rights and prerogatives of a County Palatine, as far as regarded seignory or territorial dominion, and that to a great extent by Earls. # That when the Earldom was augmented into a Duchy, the circumstances attending to its creation, as well as the language of the Duchy Charter, not only support and confirm natural presumption, that the new and higher title was to be accompanied with at least as great dignity, power, and prerogative as the Earls enjoyed, but also afforded evidence that the Duchy was to be invested with still more extensive rights and privileges. # The Duchy Charters have always been construed and treated, not merely by the Courts of Judicature, but also by the Legislature of the Country, as having vested in the Dukes of Cornwall the whole territorial interest and dominion of the Crown in and over the entire County of Cornwall.However, the term '

county palatine

In England, Wales and Ireland a county palatine or palatinate was an area ruled by a hereditary nobleman enjoying special authority and autonomy from the rest of a kingdom. The name derives from the Latin adjective ''palātīnus'', "relating t ...

' appears not to have been used historically of Cornwall, and the duchy did not have as much autonomy as the County Palatine of Durham

The County Palatine of Durham was a jurisdiction in the North of England, within which the bishop of Durham had rights usually exclusive to the monarch. It developed from the Liberty of Durham, which emerged in the Anglo-Saxon period. The g ...

, which was ruled by the Prince-Bishop of Durham. However, whilst not specifically called a county palatine, the officers of the duchy made the observation (Duchy Preliminary Statement – Cornish Foreshore Dispute 1856):

The Dukes also had their own escheators in Cornwall, and it is deserving of notice that in the saving clause of the Act of Escheators, 1 Henry VIII., c. 8, s. 5 (as is the case in numerous other acts of Parliament), the Duchy of Cornwall is classed with counties undoubtedly palatinate.

The stannaries and their revival

In 1974, a group claimed to be a revivedCornish Stannary Parliament

The Cornish Stannary Parliament (officially The Convocation of the Tinners of Cornwall) was the representative body of the Cornish stannaries, which were chartered in 1201 by King John. In spite of the name, the Parliament was not a Cornish n ...

and have the ancient right of Cornish tin-miners' assemblies to veto legislation from Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, although it opposed the Duchy of Cornwall. In 1977 the Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru ( ; , ; officially Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, and often referred to simply as Plaid) is a centre-left, Welsh nationalist list of political parties in Wales, political party in Wales, committed to Welsh independence from th ...

MP Dafydd Wigley in Parliament asked the Attorney General for England and Wales

His Majesty's Attorney General for England and Wales is the chief legal adviser to the sovereign and Government in affairs pertaining to England and Wales as well as the highest ranking amongst the law officers of the Crown. The attorney gener ...

, Samuel Silkin, if he would provide the date upon which enactments of the Charter of Pardon of 1508 were rescinded. A letter in reply, received from the Lord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

on 14 May 1977 and now held at the National Library of Wales

The National Library of Wales (, ) in Aberystwyth is the national legal deposit library of Wales and is one of the Welsh Government sponsored bodies. It is the biggest library in Wales, holding over 6.5 million books and periodicals, and the l ...

, stated that the charter had never been formally withdrawn or amended, however that "no doubt has ever been expressed" that Parliament could legislate for the stannaries without the need to seek the consent of the stannators. The group seem to have been inactive since 2008.

Moves for a change of constitutional status

Campaigns for fuller regional autonomy

An early campaign for an independent Cornwall was put forward during the firstEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

by Sir Richard Grenville, 1st Baronet. He tried to use "Cornish particularist sentiment" to gather support for the Royalist cause. The Cornish were fighting for their Royalist privileges, notably the Duchy

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a country, territory, fiefdom, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or Queen regnant, queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important differe ...

and Stannaries and he put a plan to the Prince which would, if implemented, have created a semi-independent Cornwall.

In the same vein, the Cornish Constitutional Convention – composed of a number of political groups in Cornwall (including Mebyon Kernow) – gathered about 50,000 signatures in 2000 on a petition to create a Cornish Assembly

A Cornish Assembly () is a proposed devolved law-making assembly for Cornwall along the lines of the Scottish Parliament, the Senedd (Welsh Parliament) and the Northern Ireland Assembly in the United Kingdom.

The campaign for Cornish devolut ...

resembling the National Assembly for Wales

The Senedd ( ; ), officially known as the Welsh Parliament in English and () in Welsh, is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Wales. A democratically elected body, Its role is to scrutinise the Welsh Government and legislate on devolve ...

. The petition was undertaken in the context of an ongoing debate on whether to devolve power to the English regions, of which Cornwall is part of the South West. Cornwall Council's February 2003 MORI

Mori is a Japanese and Italian surname. It is also the name of two clans in Japan, and one clan in India.

Italian surname

* Camilo Mori, Chilean painter

* Cesare Mori, Italian "Iron Prefect"

* Claudia Mori, Italian actress, singer, televisio ...

poll showed 55% in favour of an elected, fully devolved regional assembly for Cornwall and 13% against. (Previous result: 46% in favour in 2002.) However the same poll indicated an equal number of respondents in favour of a South West Regional Assembly. The campaign had the support of all five Cornish Lib Dem MPs at the time, Mebyon Kernow

Mebyon Kernow – The Party for Cornwall (, MK; Cornish language, Cornish for ''Sons of Cornwall'') is a Cornish nationalism, Cornish nationalist, Left-wing politics, centre-left political party in Cornwall, in southwestern Britain. It currentl ...

, and Cornwall Council.

Lord Whitty, as Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Department of Environment, Transport and the Regions, in the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

, recognised that Cornwall has a "special case" for devolution

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territori ...

, and on a visit to Cornwall deputy Prime Minister John Prescott said "Cornwall has the strongest regional identity in the UK."

The Conservative and Unionist Party

The Conservative and Unionist Party, commonly the Conservative Party and colloquially known as the Tories, is one of the two main political parties in the United Kingdom, along with the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party. The party sits on the Cent ...

under David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron, Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton (born 9 October 1966) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016. Until 2015, he led the first coalition government in the UK s ...

appointed Mark Prisk as Shadow Minister for Cornwall on 26 July 2007. The party said that the move was aimed at putting Cornwall's concerns "at the heart of Conservative thinking". However, the new coalition government established in 2010 under David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron, Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton (born 9 October 1966) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016. Until 2015, he led the first coalition government in the UK s ...

's leadership did not appoint a Minister for Cornwall.

Cornwall's distinctiveness as a ''national'', as opposed to regional, minority has been periodically recognised by major British papers. For example, a '' Guardian'' editorial in 1990 pointed to these differences, and warned that they should be constitutionally recognised:

''The Guardian'' also carried an article in November 2008 titled "Self-rule for Cornwall" written by the human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell.

Tatchell concluded his article with the question,

However, in a newspaper article the Conservative MP for Camborne & Redruth, George Eustice, stated in September 2014 that "However, we definitely do not need to waste money on flash new parliament buildings and yet another tier of politicians so I completely disagree with the idea of a Welsh style assembly in Cornwall."

The Labour Party in Cornwall also rejected the notion.

Cornish cultural, civic and ethnic nationalism

Some observers express surprise at enduring sentiments in Cornwall; Adrian Lee, for example, while considering Cornwall to be part of England, also considers it to have a unique status ''within'' England: SomeCornish people

Cornish people or the Cornish (, ) are an ethnic group native to, or associated with Cornwall: and a recognised national minority in the United Kingdom, which (like the Welsh people, Welsh and Breton people, Bretons) can trace its roots to ...

will, in addition to making the legal or constitutional arguments mentioned above, stress that the Cornish are a distinct ethnic group, that people in Cornwall typically refer to 'England' as beginning east of the Tamar, and that there is a Cornish language

Cornish (Standard Written Form: or , ) is a Southwestern Brittonic language, Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. Along with Welsh language, Welsh and Breton language, Breton, Cornish descends from Common Brittonic, ...

. For the first time in a UK Census, those wishing to describe their ethnicity as Cornish were given their own code number (06) on the 2001 UK Census form, alongside those for people wishing to describe themselves as English, Welsh, Irish or Scottish. About 34,000 people in Cornwall and 3,500 people in the rest of the UK wrote on their census forms in 2001 that they considered their ethnic group to be Cornish. This represented nearly 7% of the population of Cornwall and is therefore a significant phenomenon. Although happy with this development, campaigners expressed reservations about the lack of publicity surrounding the issue, the lack of a clear tick-box for the Cornish option on the census and the need to deny being British to write "Cornish" in the field provided. There have been calls for the tick box option to be extended to the Cornish; however, this petition did not meet with sufficient support (639 people signed up, 361 more were needed) for the 2011 Census, as a Welsh and English tick box option was recently agreed by the government.

See also

* Constitutional reform in the United Kingdom * Royal charters applying to Cornwall *List of topics related to Cornwall

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Cornwall:

Cornwall – ceremonial county and unitary authority area of England within the United Kingdom. Cornwall is a peninsula bordered to the north and west by ...

* Constitutional status of Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles

* Wiktionary

Wiktionary (, ; , ; rhyming with "dictionary") is a multilingual, web-based project to create a free content dictionary of terms (including words, phrases, proverbs, linguistic reconstructions, etc.) in all natural languages and in a number o ...

definitions for Cornish, nation

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective Identity (social science), identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, t ...

and ethnic group

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

References

External links

The Cornish Stannary Parliament

on

h2g2

The h2g2 website is a British-based collaborative online encyclopedia project. It describes itself as "an unconventional guide to life, the universe, and everything", in the spirit of the fictional publication ''The Hitchhiker's Guide to the ...

The Cornish Assembly – Senedh Kernow

{{DEFAULTSORT:Constitutional Status of Cornwall Politics of Cornwall Home rule in the United Kingdom Constitution of the United Kingdom Politics of the United Kingdom Government of the United Kingdom Law of the United Kingdom Cornish nationalism Legal history of the United Kingdom