Since the time of

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;["Engels"](_blank)

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.[communist society

In Marxist thought, a communist society or the communist system is the type of society and economic system postulated to emerge from technological advances in the productive forces, representing the ultimate goal of the political ideology of ...]

, leading to a variety of different communist ideologies.

These span

philosophical

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

,

social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives fro ...

,

political

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

and

economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

ideologies and

movements

Movement may refer to:

Generic uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Movement (sign language), a hand movement when signing

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

* Movement (music), a division of a larger c ...

, and can be split into three broad categories: Marxist-based ideologies, Leninist-based ideologies, and Non-Marxist ideologies, though influence between the different ideologies is found throughout and key theorists may be described as belonging to one or important to multiple ideologies.

Background

Communist ideologies notable enough in the

history of communism

The history of communism encompasses a wide variety of ideologies and political movements sharing the core principles of common ownership of wealth, economic enterprise, and property. Most modern forms of communism are grounded at least nomina ...

include

philosophical

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

,

social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives fro ...

,

political

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

and

economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

ideologies and

movements

Movement may refer to:

Generic uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Movement (sign language), a hand movement when signing

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

* Movement (music), a division of a larger c ...

whose ultimate goal is the establishment of a

communist society

In Marxist thought, a communist society or the communist system is the type of society and economic system postulated to emerge from technological advances in the productive forces, representing the ultimate goal of the political ideology of ...

, a

socioeconomic

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

order structured upon the ideas of

common ownership

Common ownership refers to holding the assets of an organization, enterprise, or community indivisibly rather than in the names of the individual members or groups of members as common property. Forms of common ownership exist in every economi ...

of the

means of production

In political philosophy, the means of production refers to the generally necessary assets and resources that enable a society to engage in production. While the exact resources encompassed in the term may vary, it is widely agreed to include the ...

and the absence of

social class

A social class or social stratum is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the working class and the Bourgeoisie, capitalist class. Membership of a social class can for exam ...

es,

money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are: m ...

and the

state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

.

Self-identified communists hold a variety of views, including

libertarian communism (

anarcho-communism

Anarchist communism is a far-left political ideology and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private real property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and se ...

and

council communism

Council communism or councilism is a current of communism, communist thought that emerged in the 1920s. Inspired by the German Revolution of 1918–1919, November Revolution, council communism was opposed to state socialism and advocated wor ...

),

Marxist communism (

left communism

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices held by Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions ...

,

libertarian Marxism

Libertarian socialism is an anti-authoritarian and anti-capitalist political current that emphasises self-governance and workers' self-management. It is contrasted from other forms of socialism by its rejection of state ownership and from other ...

,

Maoism

Maoism, officially Mao Zedong Thought, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed while trying to realize a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic o ...

,

Leninism

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

,

Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism () is a communist ideology that became the largest faction of the History of communism, communist movement in the world in the years following the October Revolution. It was the predominant ideology of most communist gov ...

, and

Trotskyism

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

),

non-Marxist communism, and

religious communism (

Christian communism

Christian communism is a theological view that the teachings of Jesus compel Christians to support religious communism. Although there is no universal agreement on the exact dates when communistic ideas and practices in Christianity began, man ...

,

Islamic communism

Islamic socialism is a political philosophy that incorporates elements of Islam into a system of socialism. As a term, it was coined by various left-wing Muslim leaders to describe a more spiritual form of socialism. Islamic socialists believe ...

and

Jewish communism). While it originates from the works of 19th century German philosophers

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;["Engels"](_blank)

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.[classical Marxism

Classical Marxism is the body of economic, philosophical, and sociological theories expounded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their works, as contrasted with orthodox Marxism, Marxism–Leninism, and autonomist Marxism which emerged after t ...]

while rejecting or modifying other aspects. Many communist schools of thought have sought to combine Marxian concepts and non-Marxian concepts which has then led to contradictory conclusions. However, there is a movement toward the recognition that

historical materialism

Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx located historical change in the rise of Class society, class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods.

Karl Marx stated that Productive forces, techno ...

and

dialectical materialism

Dialectical materialism is a materialist theory based upon the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels that has found widespread applications in a variety of philosophical disciplines ranging from philosophy of history to philosophy of scien ...

remains the fundamental aspect of all Marxist communist schools of thought. The offshoots of Marxism–Leninism are the most well-known of these and have been a driving force in

international relations

International relations (IR, and also referred to as international studies, international politics, or international affairs) is an academic discipline. In a broader sense, the study of IR, in addition to multilateral relations, concerns al ...

during most of the 20th century.

Marxist communism

Marxism

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that views class relations and social conflict using a materialist interpretation of historical development and takes a dialectical view of social transformation.

It originates from the works of 19th century German philosophers

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;["Engels"](_blank)

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.[Classical Marxism

Classical Marxism is the body of economic, philosophical, and sociological theories expounded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their works, as contrasted with orthodox Marxism, Marxism–Leninism, and autonomist Marxism which emerged after t ...]

is the economic, philosophical and sociological theories expounded by Marx and Engels as contrasted with later developments in Marxism, especially

Leninism

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

and

Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism () is a communist ideology that became the largest faction of the History of communism, communist movement in the world in the years following the October Revolution. It was the predominant ideology of most communist gov ...

.

Under the

capitalist mode of production, this struggle materializes between the minority (the

bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

), who own the

means of production

In political philosophy, the means of production refers to the generally necessary assets and resources that enable a society to engage in production. While the exact resources encompassed in the term may vary, it is widely agreed to include the ...

, and the vast majority of the population (the

proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian or a . Marxist ph ...

), who produce goods and services. Starting with the concept that

social change

Social change is the alteration of the social order of a society which may include changes in social institutions, social behaviours or social relations. Sustained at a larger scale, it may lead to social transformation or societal transformat ...

occurs because of the struggle between different

classes within society who are under contradiction against each other, a Marxist would conclude that

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

exploits and oppresses the proletariat, therefore capitalism will inevitably lead to a

proletarian revolution

A proletarian revolution or proletariat revolution is a social revolution in which the working class attempts to overthrow the bourgeoisie and change the previous political system. Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialist ...

. In a socialist society,

private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental Capacity (law), legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which is owned by a state entity, and from Collective ownership ...

—in the form of the means of production—would be replaced by co-operative ownership. A socialist economy would not base production on the creation of private profits, but on the criteria of satisfying human needs—that is,

production would be carried out directly for use. As Friedrich Engels said: "Then the capitalist mode of appropriation, in which the product enslaves first the producer, and then the appropriator, is replaced by the mode of appropriation of the product that is based upon the nature of the modern means of production; upon the one hand, direct social appropriation, as means to the maintenance and extension of production - on the other, direct individual appropriation, as means of subsistence and of enjoyment".

Marxian economics

Marxian economics, or the Marxian school of economics, is a heterodox school of political economic thought. Its foundations can be traced back to Karl Marx's critique of political economy. However, unlike critics of political economy, Marxian ...

and its proponents view capitalism as economically unsustainable and incapable of improving the living standards of the population due to its need to compensate for

falling rates of profit by cutting employee's wages, social benefits and pursuing military aggression. The

socialist system would succeed capitalism as humanity's mode of production through workers'

revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

. According to Marxian

crisis theory

Crisis theory, concerning the causes and consequences of the tendency for the rate of profit to fall in a capitalist system, is associated with Marxian critique of political economy, and was further popularised through Marxist economics.

His ...

,

socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

is not an inevitability, but an economic necessity.

Orthodox Marxism

Orthodox Marxism is the body of Marxist thought that emerged after the death of Marx and which became the official philosophy of the socialist movement as represented in the

Second International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

until

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in 1914. Orthodox Marxism aims to simplify, codify and systematize Marxist method and theory by clarifying the perceived ambiguities and contradictions of classical Marxism. The philosophy of orthodox Marxism includes the understanding that material development (advances in technology in the

productive forces

Productive forces, productive powers, or forces of production ( German: ''Produktivkräfte'') is a central idea in Marxism and historical materialism.

In Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels' own critique of political economy, it refers to the combin ...

) is the primary agent of change in the structure of society and of human social relations, and that social systems and their relations (e.g.

feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

, capitalism and so on) become contradictory and inefficient as the productive forces develop, which results in some form of social revolution arising in response to the mounting contradictions. This revolutionary change is the vehicle for fundamental society-wide changes and ultimately leads to the emergence of new

economic system

An economic system, or economic order, is a system of production, resource allocation and distribution of goods and services within an economy. It includes the combination of the various institutions, agencies, entities, decision-making proces ...

s.

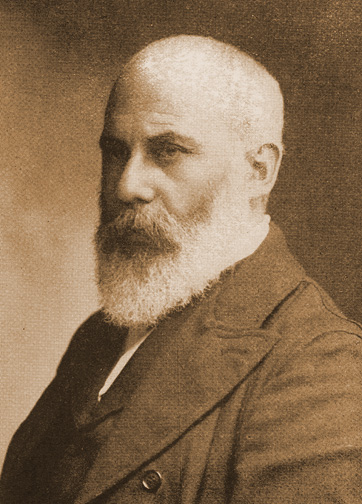

As a term, orthodox Marxism refers to the methods of historical materialism and of dialectical materialism and not the normative aspects inherent to classical Marxism, without implying dogmatic adherence to the results of Marx's investigations. One of the most important historical proponents of Orthodox Marxism was the Czech-Austrian theorist

Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian Marxism, Marxist theorist. A leading theorist of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Second International, Kautsky advocated orthodox Marxism, a ...

.

Neo-Marxism

Neo-Marxism is a

Marxist school of thought originating from 20th-century approaches

to amend or extend

Marxism and

Marxist theory

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Western Marxism, which drew f ...

, typically by incorporating elements from other intellectual traditions such as

critical theory

Critical theory is a social, historical, and political school of thought and philosophical perspective which centers on analyzing and challenging systemic power relations in society, arguing that knowledge, truth, and social structures are ...

,

psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek language, Greek: and is a set of theories and techniques of research to discover unconscious mind, unconscious processes and their influence on conscious mind, conscious thought, emotion and behaviour. Based on The Inte ...

, or

existentialism

Existentialism is a family of philosophical views and inquiry that explore the human individual's struggle to lead an authentic life despite the apparent absurdity or incomprehensibility of existence. In examining meaning, purpose, and valu ...

. The

Frankfurt School

The Frankfurt School is a school of thought in sociology and critical theory. It is associated with the University of Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, Institute for Social Research founded in 1923 at the University of Frankfurt am Main ...

is often described as neo-Marxist.

Leninist-based ideologies

Leninism

Leninism is a political theory for the organisation of a revolutionary

vanguard party

Vanguardism, a core concept of Leninism, is the idea that a revolutionary vanguard party, composed of the most conscious and disciplined workers, must lead the proletariat in overthrowing capitalism and establishing socialism, ultimately progres ...

and the achievement of a

dictatorship of the proletariat as political prelude to the establishment of socialism. Developed by and named for the Russian revolutionary

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, from the

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

faction of the Bolshevik-

Menshevik

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

split in the

Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

, Leninism comprises political and economic theories developed from orthodox Marxism and Lenin's interpretations of Marxist theories, including his original theoretical contributions such as his

analysis

Analysis (: analyses) is the process of breaking a complex topic or substance into smaller parts in order to gain a better understanding of it. The technique has been applied in the study of mathematics and logic since before Aristotle (38 ...

of

imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

, principles of

party organization and the implementation of socialism through

revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

and

New Economic Policy reform thereafter, for practical application to the socio-political conditions of the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

of the early 20th century.

Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a political ideology developed by

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

in the late 1920s. Based on Stalin's understanding and synthesis of both Marxism and Leninism, it was the official

state ideology of the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and the parties of the

Communist International

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internationa ...

after

Bolshevisation

Bolshevization of the Communist International has at least two meanings. First it meant to independently change the way of working of new communist parties, such as that in the UK in the early 1920s. Secondly was the process from 1924 by which th ...

. After the death of Lenin in 1924, Stalin established universal ideological orthodoxy among the

Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

, the Soviet Union and the Communist International to establish universal Marxist–Leninist

praxis

Praxis may refer to:

Philosophy and religion

*Praxis (process), the process by which a theory, lesson, or skill is enacted, practised, embodied, or realised

* Praxis model, a way of doing theology

* Praxis (Byzantine Rite), the practice of fai ...

. In the late 1930s, Stalin's official textbook ''

The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks)'' (1938), made the term Marxism–Leninism common political-science usage among communists and non-communists.

The purpose of Marxism–Leninism is the revolutionary transformation of a capitalist state into a socialist state by way of

two-stage revolution led by a vanguard party of professional revolutionaries, drawn from the proletariat.

To realise the two-stage transformation of the state, the vanguard party establishes the dictatorship of the proletariat and determines policy through democratic centralism. The Marxist–Leninist

communist party is the vanguard for the political, economic and social transformation of a capitalist society into a socialist society which is the lower stage of socio-economic development and progress towards the upper-stage

communist society

In Marxist thought, a communist society or the communist system is the type of society and economic system postulated to emerge from technological advances in the productive forces, representing the ultimate goal of the political ideology of ...

which is

stateless and

classless

A classless society is a society in which no one is born into a social class like in a class society. Distinctions of wealth, income, education, culture, or social network might arise and would only be determined by individual experience an ...

, yet it features public ownership of the means of production, accelerated

industrialisation

Industrialisation ( UK) or industrialization ( US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive reorganisation of an economy for th ...

, pro-active development of society's productive forces (research and development) and

nationalised

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with ...

natural resources.

As the official ideology of the Soviet Union, Marxism–Leninism was adopted by communist parties worldwide with variation in local application. Parties with a Marxist–Leninist understanding of the historical development of socialism advocate for the nationalisation of natural resources and

monopolist

A monopoly (from Greek and ) is a market in which one person or company is the only supplier of a particular good or service. A monopoly is characterized by a lack of economic competition to produce a particular thing, a lack of viable s ...

industries of capitalism and for their internal democratization as part of the transition to

workers' control

Workers' control is participation in the management of factories and other commercial enterprises by the people who work there. It has been variously advocated by anarchists, socialists, communists, social democrats, distributists and Christi ...

. The economy under such a government is primarily coordinated through a universal

economic plan

A market intervention is a policy or measure that modifies or interferes with a market, typically done in the form of state action, but also by philanthropic and political-action groups. Market interventions can be done for a number of reaso ...

with varying degrees of

market

Market is a term used to describe concepts such as:

*Market (economics), system in which parties engage in transactions according to supply and demand

*Market economy

*Marketplace, a physical marketplace or public market

*Marketing, the act of sat ...

distribution. Since the fall of the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries, many communist parties of the world today continue to use Marxism–Leninism as their method of understanding the conditions of their respective countries.

A variety of currents developed from Marxism-Leninism have gained prominence in various countries, including

Bolshevism

Bolshevism (derived from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Leninist and later Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined p ...

and

Mariáteguism.

Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and related policies implemented from

1924 to 1953 by Stalin. Stalinist policies and ideas that were developed in the Soviet Union included rapid industrialisation, the theory of

socialism in one country,

collectivisation of agriculture,

intensification of the class struggle under socialism

The intensification of the class struggle along with the development of socialism is a component of the theory of Stalinism.

Description

The theory was one of the cornerstones of Stalinism in the internal politics of the Soviet Union. Although t ...

, a

cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader,Cas Mudde, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create ...

, and subordination of the interests of foreign

communist parties to those of the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

(Bolsheviks), deemed by Stalinism to be the leading vanguard party of

communist revolution

A communist revolution is a proletarian revolution inspired by the ideas of Marxism that aims to replace capitalism with communism. Depending on the type of government, the term socialism can be used to indicate an intermediate stage between ...

at the time.

As a political term, it has a variety of uses, but most commonly it is used as a

pejorative

A pejorative word, phrase, slur, or derogatory term is a word or grammatical form expressing a negative or disrespectful connotation, a low opinion, or a lack of respect toward someone or something. It is also used to express criticism, hosti ...

shorthand for Marxism–Leninism by a variety of competing political tendencies such as capitalism and

Trotskyism

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

. Although Stalin himself repudiated any qualitatively original contribution to Marxism, the communist movement usually credits him with systematizing and expanding the ideas of Lenin into the ideology of Marxism–Leninism as a distinct body of work. In this sense, Stalinism can be thought of as being roughly equivalent to Marxism–Leninism, although this is not universally agreed upon.

At other times, the term is used as a general umbrella term—again pejoratively—to describe a wide variety of political systems and governments. In this sense, it can be seen as being roughly equivalent to

actually existing socialism, although sometimes it is used to describe totalitarian governments that are not socialist.

Some of the contributions to communist theory that Stalin is particularly known for are the following:

* The theoretical work concerning nationalities as seen in ''

Marxism and the National Question

''Marxism and the National Question'' () is a short work of Marxist theory written by Joseph Stalin in January 1913 while living in Vienna. First published as a pamphlet and frequently reprinted, the essay by the ethnic Georgian Stalin was reg ...

''.

* The notion of socialism in one country.

*

Marxism and Problems of Linguistics

"Marxism and Problems of Linguistics" () is an article written by Joseph Stalin, most of which was first published on 20 June 1950, in the newspaper ''Pravda'' (the "answers" attached at the end came later, in July and August), and was in the sam ...

.

* The theory of

aggravation of class struggle under socialism

The intensification of the class struggle along with the development of socialism is a component of the theory of Stalinism.

Description

The theory was one of the cornerstones of Stalinism in the internal politics of the Soviet Union. Although t ...

, a theoretical base supporting the repression of political opponents as necessary.

Trotskyism

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

and his supporters organized into the

Left Opposition

The Left Opposition () was a faction within the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1923 to 1927 headed '' de facto'' by Leon Trotsky. It was formed by Trotsky to mount a struggle against the perceived bureaucratic degeneration within th ...

and their platform became known as Trotskyism. Stalin eventually succeeded in gaining control of the Soviet regime and Trotskyist attempts to remove Stalin from power resulted in Trotsky's exile from the Soviet Union in 1929. During Trotsky's exile, mainstream communism fractured into two distinct branches, i.e. Trotskyism and Stalinism. Trotskyism supports the theory of

permanent revolution

Permanent revolution is the strategy of a revolutionary class pursuing its own interests independently and without compromise or alliance with opposing sections of society. As a term within Marxist theory, it was first coined by Karl Marx and ...

and

world revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class. For theorists, these revolutions will not necessarily occur simultaneously, but whe ...

instead of the two-stage theory and socialism in one country. It supported

proletarian internationalism

Proletarian internationalism, sometimes referred to as international socialism, is the perception of all proletarian revolutions as being part of a single global class struggle rather than separate localized events. It is based on the theory th ...

and another communist revolution in the Soviet Union which Trotsky claimed had become a

degenerated worker's state under the leadership of Stalin in which class relations had re-emerged in a new form, rather than the dictatorship of the proletariat. In 1938, Trotsky founded the

Fourth International

The Fourth International (FI) was a political international established in France in 1938 by Leon Trotsky and his supporters, having been expelled from the Soviet Union and the Communist International (also known as Comintern or the Third Inte ...

, a Trotskyist rival to the Stalinist Communist International.

Trotskyist ideas became more prominent through the 1960s, having found echo among political movements in some countries in Asia and Latin America, especially in Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, and Sri Lanka. Many Trotskyist organizations are also active in more stable, developed countries in North America and Western Europe.

Trotsky's politics differed sharply from those of Stalin and Mao, most importantly in declaring the need for an international proletarian revolution (rather than socialism in one country) and unwavering support for a true dictatorship of the proletariat-based on democratic principles. As a whole, Trotsky's theories and attitudes were never accepted in Marxist–Leninist circles after Trotsky's expulsion, either within or outside of the Soviet Bloc. This remained the case even after the "

Secret Speech

"On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences" () was a report by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, made to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on 25 Februa ...

" and subsequent events critics claim exposed the fallibility of Stalin.

Trotsky's followers claim to be the heirs of Lenin in the same way that mainstream Marxist–Leninists do. There are several distinguishing characteristics of this school of thought—foremost is the theory of permanent revolution, contrasted to the theory of socialism in one country. This stated that in less-developed countries the bourgeoisie were too weak to lead their own

bourgeois-democratic revolutions. Due to this weakness, it fell to the proletariat to carry out the bourgeois revolution. With power in its hands, the proletariat would then continue this revolution permanently, transforming it from a national bourgeois revolution to a socialist international revolution. Another shared characteristic between Trotskyists is a variety of theoretical justifications for their negative appraisal of the post-Lenin Soviet Union after Trotsky was expelled by a majority vote from the

All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

and subsequently from the Soviet Union. As a consequence, Trotsky defined the Soviet Union under Stalin as a planned economy ruled over by a bureaucratic caste. Trotsky advocated overthrowing the government of the Soviet Union after he was expelled from it. Trotskyist currents include

orthodox Trotskyism,

third camp

The third camp, also known as third camp socialism or third camp Trotskyism, is a branch of socialism that aims to oppose both capitalism and Stalinism by supporting the organised working class as a "third camp".

The term arose early during W ...

,

Posadism,

Pabloism, and

Morensim.

Maoism

Maoism is the Marxist–Leninist trend of communism associated with

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

and was mostly practised within the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. Khrushchev's reforms heightened ideological differences between China and the Soviet Union, which became increasingly apparent in the 1960s. As the

Sino-Soviet split

The Sino-Soviet split was the gradual worsening of relations between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) during the Cold War. This was primarily caused by divergences that arose from their ...

in the international communist movement turned toward open hostility, China portrayed itself as a leader of the underdeveloped world against the two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union.

Parties and groups that supported the

Communist Party of China

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

in their criticism against the new Soviet leadership proclaimed themselves as

anti-revisionist and denounced the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the parties aligned with it as

revisionist "

capitalist roader

In Maoism, a capitalist roader is a person or group who demonstrates a marked tendency to bow to pressure from bourgeois forces and subsequently attempts to pull the Chinese Communist Revolution in a capitalist direction. If allowed to do so, thes ...

s". The Sino-Soviet split resulted in divisions amongst communist parties around the world. Notably, the

Party of Labour of Albania

The Party of Labour of Albania (PLA), also referred to as the Albanian Workers' Party (AWP), was the ruling and sole legal party of Albania during the communist period (1945–1991). It was founded on 8 November 1941 as the Communist Party of ...

sided with the People's Republic of China. Effectively, the communist party under Mao Zedong's leadership became the rallying forces of a parallel international communist tendency. The ideology of the Chinese communist party, Marxism–Leninism–Mao Zedong Thought, was adopted by many of these groups.

After Mao's death and his replacement by

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping also Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Teng Hsiao-p'ing; born Xiansheng (). (22 August 190419 February 1997) was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and political theorist who served as the paramount leader of the People's R ...

, the international Maoist movement diverged. One sector accepted the new leadership in China whereas a second renounced the new leadership and reaffirmed their commitment to Mao's legacy and a third renounced Maoism altogether and aligned with

Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

.

[; ; ; ]

Deng Xiaoping Theory

Drawing inspiration from Lenin's New Economic Policy, Dengism is a political and economic ideology first developed by Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping. The theory does not claim to reject Marxism–Leninism or Mao Zedong Thought, but instead it seeks to adapt them to the existing socio-economic conditions of China. Deng also stressed

opening China to the outside world, the implementation of

one country, two systems

"One country, two systems" is a constitutional principle of the People's Republic of China (PRC) describing the governance of the special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macau.

Deng Xiaoping developed the one country, two systems ...

and through the phrase "

seek truth from facts

"Seek truth from facts" is a historically established idiomatic expression ('' chengyu'') in the Chinese language that first appeared in the '' Book of Han''. Originally, it described an attitude toward study and research. Popularized by Chinese ...

" an advocate of political and economic

pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that views language and thought as tools for prediction, problem solving, and action, rather than describing, representing, or mirroring reality. Pragmatists contend that most philosophical topics� ...

.

As reformist communism and a branch of Maoism, Dengism is often criticized by traditional Maoists. Dengists believe that isolated in our current international order and with an extremely underdeveloped economy it is first and foremost necessary to bridge the gap between China and Western capitalism as quickly as possible in order for socialism to be successful (see the theory of

primary stage of socialism

The primary stage of socialism (sometimes referred to as the preliminary stage of socialism),''Properly Understand Theories Concerning Preliminary Stage of Socialism'', by Wei Xinghua and Sang Baichuan. 1998. Journal of Renmin University of Chi ...

). In order to encourage and promote the advancement of productivity by creating competition and innovation, Dengist thought promotes the idea that the PRC needs to introduce certain market elements in a socialist country. Dengists still believe that China needs public ownership of land, banks, raw materials and strategic central industries so a democratically elected government can make decisions on how to use them for the benefit of the country as a whole instead of the land owners, but at the same time private ownership is allowed and encouraged in industries of finished goods and services. According to the Dengist theory, private owners in those industries are not a bourgeoisie. Because in accordance with Marxist theory, bourgeois owns land and raw materials. In Dengist theory, private company owners are called civil run enterprises.

China was the first country that adopted this belief. It boosted its economy and achieved the Chinese economic miracle. It has increased the Chinese GDP growth rate to over 8% per year for thirty years and China now has the second highest GDP in the world. Due to the influence of Dengism, Vietnam and Laos have also adopted similar beliefs and policies, allowing Laos to increase its real GDP growth rate to 8.3%. Cuba is also starting to embrace such ideas. Dengists take a very strong position against any form of personality cults which appeared in the Soviet Union during Stalin's rule and the current North Korea.

Marxism–Leninism–Maoism

Marxism–Leninism–Maoism is a political philosophy that builds upon Marxism–Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought. It was first formalised by the Peruvian communist party

Shining Path

The Shining Path (, SL), self-named the Communist Party of Peru (, abbr. PCP), is a far-left political party and guerrilla group in Peru, following Marxism–Leninism–Maoism and Gonzalo Thought. Academics often refer to the group as the ...

in 1988.

The synthesis of Marxism–Leninism–Maoism did not occur during the life of Mao. From the 1960s, groups that called themselves Maoist, or which upheld Marxism–Leninism–Mao Zedong Thought, were not unified around a common understanding of Maoism and had instead their own particular interpretations of the political, philosophical, economical and military works of Mao. Maoism as a unified, coherent stage of Marxism was not synthesized until the late 1980s through the experience of the people's war waged by the Shining Path. This led the Shining Path to posit Maoism as the newest development of Marxism in 1988.

Since then, it has grown and developed significantly and has served as an animating force of revolutionary movements in countries such as Brazil,

Colombia, Ecuador, India, Nepal and the Philippines and has also led to efforts being undertaken towards the constitution or reconstitution of communist parties in countries such as Austria, France, Germany, Sweden and the United States.

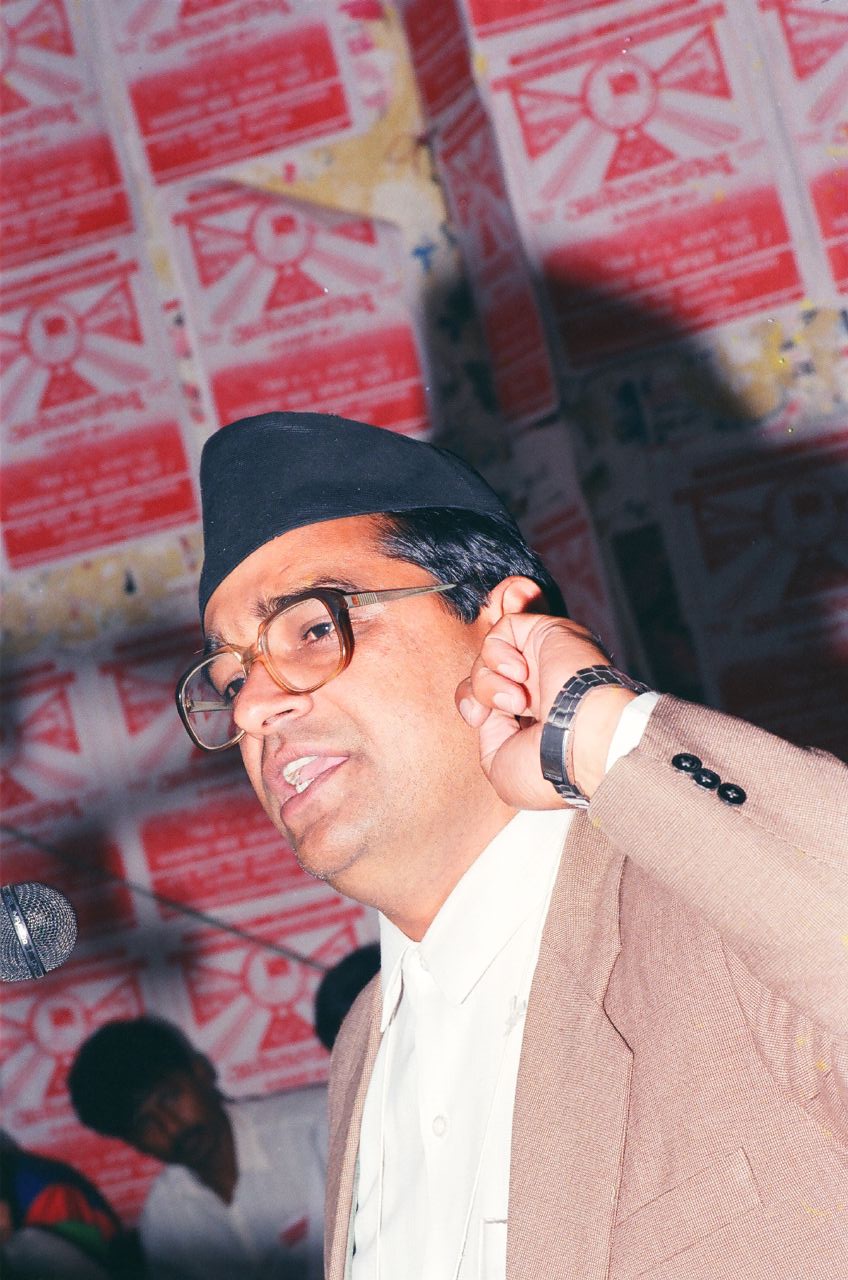

Prachanda Path

Marxism–Leninism–Maoism–Prachanda Path is the ideological line of the

Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre)

The Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) (), abbreviated CPN (Maoist Centre) or CPN (MC), is the third largest List of political parties in Nepal, political party in Nepal and a member party of Socialist Front (Nepal), Samajbadi Morcha. I ...

. It is considered to be a further development of Marxism–Leninism and Maoism. It is named after the leader of the CPN(M), Pushpa Kamal Dahal, commonly known as

Prachanda.

Prachanda Path was proclaimed in 2001 and its formulation was partially inspired by the Shining Path which refers to its ideological line as

Marxism–Leninism–Maoism–Gonzalo Thought. Prachanda Path does not make an ideological break with Marxism–Leninism or Maoism, but rather it is an extension of these ideologies based on the political situation of Nepal. The doctrine came into existence after it was realized that the ideology of Marxism–Leninism and Maoism could not be practiced as done in the past, therefore Prachanda Path based on the circumstances of Nepalese politics was adopted by the party. Prachanda's positions are seen by some Marxist–Leninist–Maoists around the world as "revisionist".

Other Maoist tendencies

Other Maoist-based tendencies include

Maoism–Third Worldism,

New Democracy

New Democracy, or the New Democratic Revolution, is a type of democracy in Marxism, based on Mao Zedong's Bloc of Four Social Classes theory in post-revolutionary China which argued originally that democracy in China would take a path that w ...

in the Philippines, and

Naxalism, an ongoing Maoist-based insurgency in India.

People's Multiparty Democracy (Madanism)

People's Multiparty Democracy (, abbreviated , also called Marxism-Leninism-Madanism ()) refers to the ideological line of the

Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist)

The Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) (; Abbreviation, abbr. CPN (UML)) is a Communism in Nepal, communist List of political parties in Nepal, political party in Nepal. The party emerged as one of the major parties in Nepal af ...

and

Nepal Communist Party

The Nepal Communist Party, abbreviated NCP (, ) was a communist party in Nepal that existed from 2018 to 2021. It was founded on 17 May 2018, from the unification of two Left-wing politics, leftist parties, Communist Party of Nepal (Unified M ...

. This thought abandons the traditional Leninist idea of a revolutionary communist

vanguard party

Vanguardism, a core concept of Leninism, is the idea that a revolutionary vanguard party, composed of the most conscious and disciplined workers, must lead the proletariat in overthrowing capitalism and establishing socialism, ultimately progres ...

in favor of a

democratic multi-party system

In political science, a multi-party system is a political system where more than two meaningfully-distinct political parties regularly run for office and win elections. Multi-party systems tend to be more common in countries using proportional ...

.

It is considered an extension of Marxism–Leninism by

Madan Bhandari, the CPN-UML leader who developed it, and is based on the local

politics of Nepal.

Xi Jinping Thought

Xi Jinping Thought is an ideological doctrine based on the writings, speeches and policies of

Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

general secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, Power (social and political), power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the org ...

Xi Jinping

Xi Jinping, pronounced (born 15 June 1953) is a Chinese politician who has been the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Chairman of the Central Military Commission (China), chairman of the Central Military Commission ...

. According to the CCP, Xi Jinping Thought "builds on and further enriches" previous party ideologies and has also been called as the "Marxism of contemporary China and of the 21st century". It consists of 14-point fundamental principles, which were announced together with Xi Jinping Thought.

Hoxhaism

Hoxhaism is an anti-revisionist Marxist-Leninist variant that appeared after the

ideological row between the Communist Party of China and the Party of Labour of Albania in 1978.

The Albanians rallied a new separate international tendency. This tendency would demarcate itself by a strict defense of the legacy of Stalin and fierce criticism of virtually all other communist groupings as revisionist.

Critical of the United States, Soviet Union and China,

Enver Hoxha

Enver Halil Hoxha ( , ; ; 16 October 190811 April 1985) was an Albanian communist revolutionary and politician who was the leader of People's Socialist Republic of Albania, Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985. He was the Secretary (titl ...

declared the latter two to be

social-imperialist and condemned the

Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia

On 20–21 August 1968, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four fellow Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Republic of Bulgaria, and the Hungarian People's Republic. The in ...

by withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact in response. Hoxhaism asserts the right of nations to pursue socialism by different paths, dictated by the conditions in those countries. Hoxha declared Albania to be the world's only state legitimately adhering to Marxism–Leninism after 1978. The Albanians were able to win over a large share of the Maoists, mainly in Latin America such as the

Popular Liberation Army and the

Marxist–Leninist Communist Party of Ecuador, but it also had a significant

international following in general.

After the fall of the communist government in Albania, the pro-Albanian parties are grouped around an

international conference and the publication ''Unity and Struggle''.

Titoism

Titoism is described as the post-World War II policies and practices associated with

Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito ( ; , ), was a Yugoslavia, Yugoslav communist revolutionary and politician who served in various positions of national leadership from 1943 unti ...

during the Cold War, characterized by an

opposition to the Soviet Union.

[; ; ; ]

Elements of Titoism are characterized by policies and practices based on the principle that in each country, the means of attaining ultimate communist goals must be dictated by the conditions of that particular country rather than by a pattern set in another country. During Josip Broz Tito's era, this specifically meant that the communist goal should be pursued independently of and often in opposition to the policies of the Soviet Union. The term was originally meant as a pejorative and was labeled by Moscow as a heresy during the period of tensions between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia known as the

Informbiro period from 1948 to 1955. The implementation of

socialist self-management which to move the managing of companies into the hands of workers and to separate the management from the state.

It was also meant to demonstrate the viability of a third way between the capitalist

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and the socialist

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. From 1949 the central government began to cede power to communal local governments, seeking to decentralise the government and work towards a

withering away of the state

The withering away of the state is a Marxist concept coined by Friedrich Engels referring to the expectation that, with the realization of socialism, the state will eventually become obsolete and cease to exist as society will be able to gover ...

.

Rankovićism disagreed with this decentralisation, viewing it as a threat to the stability of Yugoslavia.

Unlike the rest of Eastern Bloc which fell under Stalin's influence post-World War II,

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

remained independent from Moscow due to the strong leadership of Tito and the fact that the

Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian language, Macedonian, and Slovene language, Slovene: , officially the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska i partizanski odr ...

liberated Yugoslavia with only limited help from the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

.

It became the only country in the Balkans to resist pressure from Moscow to join the Warsaw Pact and remained "socialist, but independent" right up until the collapse of Soviet socialism in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Throughout his time in office, Josip Broz Tito and party leadership took pride in Yugoslavia's independence from the Soviet Bloc, with Yugoslavia never accepting full membership of the

Comecon

The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, often abbreviated as Comecon ( ) or CMEA, was an economic organization from 1949 to 1991 under the leadership of the Soviet Union that comprised the countries of the Eastern Bloc#List of states, Easter ...

and his open rejection of many aspects of Stalinism as the most obvious manifestations of this.

Although himself not a communist,

Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi (20 October 2011) was a Libyan military officer, revolutionary, politician and political theorist who ruled Libya from 1969 until Killing of Muammar Gaddafi, his assassination by Libyan Anti-Gaddafi ...

's

Third International Theory was heavily influenced by Titoism.

Ho Chi Minh Thought

Ho Chi Minh Thought () is a

political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

that builds upon Marxism–Leninism and the ideology of

Ho Chi Minh

(born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), colloquially known as Uncle Ho () among other aliases and sobriquets, was a Vietnamese revolutionary and politician who served as the founder and first President of Vietnam, president of the ...

. It was developed and codified by the

Communist Party of Vietnam

The Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) is the founding and sole legal party of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Founded in 1930 by Hồ Chí Minh, the CPV became the ruling party of North Vietnam in 1954 and then all of Vietnam after the col ...

and formalised in 1991. The term is used to cover political theories and policies considered as representing a form of Marxism–Leninism that has been adapted to

Vietnamese circumstances and history. Whilst the ideology is named after the Vietnamese revolutionary and President, it does not necessarily reflect the personal ideologies of Ho Chi Minh but rather the official ideology of the Communist Party of Vietnam.

As with Maoism, the core of Ho Chi Minh Thought is the belief that the peasantry is the revolutionary vanguard in pre-industrial societies rather than the proletariat. Ho Chi Minh Thought is rooted in:

*

Marxism-Leninism

* Traditional Vietnamese ideology and culture

* Eastern cultural thought:

Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, Religious Confucianism, religion, theory of government, or way of li ...

and

Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

* Western ideologies, specifically French and American political philosophy

* Ho Chi Minh's personal morality

Castroism

Castroism refers to the politics followed and enacted by the

Communist Party of Cuba

The Communist Party of Cuba (, PCC) is the sole ruling party of Cuba. It was founded on 3 October 1965 as the successor to the United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution, which was in turn made up of the 26th of July Movement and Popu ...

under the leadership of

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban politician and revolutionary who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and President of Cuba, president ...

, following a Marxist and a Leninist stance. Castro's political thought was influenced by the Cuban anti-imperialist revolutionary

José Martí

José Julián Martí Pérez (; 28 January 1853 – 19 May 1895) was a Cuban nationalism, nationalist, poet, philosopher, essayist, journalist, translator, professor, and publisher, who is considered a Cuban national hero because of his role in ...

, Marx, and

Hispanidad

(, typically translated as "Hispanicity") is a Spanish term describing a shared cultural, linguistic, or political identity among speakers of the Spanish language or members of the Hispanic diaspora. The term can have various, different implicat ...

, a movement that criticized Anglo-Saxon material values and admired the moral values of Spanish and Spanish American culture. Besides Castro's personal thought, the theory of

Che Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (14th May 1928 – 9 October 1967) was an Argentines, Argentine Communist revolution, Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and Military theory, military theorist. A majo ...

and

Jules Régis Debray have also been important influences on Castroism. The

Socialist Workers Party in the United States follows a Castroist position.

Guevarism

Guevarism is a theory of communist revolution and a

military strategy

Military strategy is a set of ideas implemented by military organizations to pursue desired Strategic goal (military), strategic goals. Derived from the Greek language, Greek word ''strategos'', the term strategy, when first used during the 18th ...

of

guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

associated with

Ernesto "Che" Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (14th May 1928 – 9 October 1967) was an Argentines, Argentine Communist revolution, Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and Military theory, military theorist. A majo ...

, who believed in the idea of Marxism–Leninism and embraced its principles. From his own experience he developed the

foco

A guerrilla foco is a small cadre of revolutionaries operating in a nation's countryside. This guerrilla organization was popularized by Che Guevara in his book ''Guerrilla Warfare (Che Guevara book), Guerrilla Warfare'', which was based on his e ...

theory of

guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

, that took inspiration from the Maoist notion of a "

protracted people's war

People's war or protracted people's war is a Maoist military strategy. First developed by the Chinese communist revolutionary leader Mao Zedong (1893–1976), the basic concept behind people's war is to maintain the support of the population a ...

", combined with Guevara's experiences in the

Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution () was the military and political movement that overthrew the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, who had ruled Cuba from 1952 to 1959. The revolution began after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état, in which Batista overthrew ...

. When there were "objective conditions" for a revolution in a country, a small "focus" guerrilla as a vanguard could create the "subjective conditions" and unleash a general popular uprising. Guevara provided the details of the guerilla warfare used in Cuba with discussion in his book ''

Guerilla Warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrorism ...

''. Guevara explained that in certain contexts the armed struggle had no place so it was necessary to use peaceful mechanisms such as participation within

representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy or electoral democracy, is a type of democracy where elected delegates represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies func ...

. Although Che stated that this line should be peaceful but "very combative, very brave" and that it could only be abandoned if its orientation in favor of representative democracy was undermined within the population. It was once such means have been exhausted that guerilla warfare should be considered and prepared.

Sankarism

Sankarism is a description of the policies enacted and positions held by the government of

Thomas Sankara

Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara (; 21 December 1949 – 15 October 1987) was a Burkinabè military officer, Marxist and Pan-Africanist revolutionary who served as the President of Burkina Faso from 1983, following his takeover in a coup, until ...

in

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country in West Africa, bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the south, and Ivory Coast to the southwest. It covers an area of 274,223 km2 (105,87 ...

. Ideologically, Sankara was a

pan-Africanist,

anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is opposition to imperialism or neocolonialism. Anti-imperialist sentiment typically manifests as a political principle in independence struggles against intervention or influenc ...

and a communist who studied the works of Marx and Lenin, who sought to reclaim the African identity of his nation and opposed

neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is the control by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony) through indirect means. The term ''neocolonialism'' was first used after World War II to refer to ...

. During his time in power he attempted to bring about what he called the "Democratic and Popular Revolution" (), a radical transformation of society with a focus on

self-sufficiency

Self-sustainability and self-sufficiency are overlapping states of being in which a person, being, or system needs little or no help from, or interaction with others. Self-sufficiency entails the self being enough (to fulfill needs), and a sel ...

. A number of organizations were formed to implement this revolution, among them the

Committees for the Defense of the Revolution

Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (), or CDR, are a network of neighborhood committees across Cuba. The organizations, described as the "eyes and ears of the Revolution," exist to help support local communities and report on "counte ...

, the

Popular Revolutionary Tribunals and the

Pioneers of the Revolution. A vast number of reforms were enacted in Burkina Faso between 1983 and 1987, including mass vaccination programs,

reforestation, elimination of

slum

A slum is a highly populated Urban area, urban residential area consisting of densely packed housing units of weak build quality and often associated with poverty. The infrastructure in slums is often deteriorated or incomplete, and they are p ...

s through new housing developments,

and the development of national infrastructure such as railway networks.

There is a strong political dissonance between the movements in modern

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country in West Africa, bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the south, and Ivory Coast to the southwest. It covers an area of 274,223 km2 (105,87 ...

which ascribe to Sankara's political legacy and ideals, a fact which the Burkinabé opposition politician

Bénéwendé Stanislas Sankara (no relation) described in 2001 as being "due to a lack of definition of the concept." The "Sankarists" range from communists and socialists to

nationalists

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, Id ...

and

populists.

The

Economic Freedom Fighters

The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) is a South African communist and black nationalist political party. It was founded by expelled former African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) president Julius Malema, and his allies, on 26 July 20 ...

(EFF) of

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, founded in 2013 by

Julius Malema

Julius Sello Malema (born 3 March 1981) is a South African politician. He is the founder and leader of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), a communist political party known for the red berets and military-style outfits worn by its members.

Be ...

, claim to take significant inspiration from Sankara in terms of both style and ideology.

Khrushchevism

Khrushchevism was a form of Marxism–Leninism which consisted of the theories and policies of

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

and his administration in the Soviet Union, through De-Stalinization, de-Stalinisation, liberal tolerance of some cultural dissent and deviance, and a more welcoming international relations policy and attitude towards foreigners.

Kadarism

Kadarism (), also commonly called ''Goulash Communism'' or the ''Hungarian Thaw'', is the variety of

socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

in Hungary following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. János Kádár and the Hungarian People's Republic imposed policies with the goal to create high-quality living standards for the people of Hungary coupled with economic reforms. These reforms fostered a sense of well-being and relative cultural freedom in Hungary with the reputation of being "the happiest barracks"

of the Eastern Bloc during the 1960s to the 1970s. With elements of regulated market economics as well as an improved human rights record, it represented a quiet reform and deviation from the Stalinist principles applied to Hungary in the previous decade. This period of "pseudo-consumerism" saw an increase of foreign affairs and consumption of consumer goods as well.

Kadarism came from a background of Imre Nagy's "Reform Communism" (1955–1956), where he argues that Marxism is a "science that cannot remain static but must develop and become more perfect".

Official policy employed different methods of administering the collectives in Hungarian society, leaving the pace of mechanization up to each separately.

Additionally, rather than enforcing the system of compulsory crop deliveries and of workdays credit the collectivizers used monthly cash wages. Later in the 1960s, cooperatives were permitted to enter into related and then general auxiliary businesses such as food processing, light industry and service industry.

Husakism

Husakism (; ) is an ideology connected with the politician Gustáv Husák of Communist Czechoslovakia which describes his policies of Normalization (Czechoslovakia), "normalization" and federalism, while following a neo-Stalinism, neo-Stalinist line. This was the state ideology of Czechoslovakia from about 1969 to about 1989, formulated by Husák, Vasil Biľak and others.

Kaysone Phomvihane Thought

Kaysone Phomvihane Thought () builds upon Marxism–Leninism and Ho Chi Minh Thought with the political philosophy developed by Kaysone Phomvihane, the first leader of the Communist Lao People's Revolutionary Party (LPRP). It was formalised by the LPRP at its 10th National Congress of the Lao People's Revolutionary Party, 10th National Congress in 2016.

Other Marxist-based ideologies

Libertarian Marxism

Libertarian Marxism is a broad scope of Philosophy and economics, economic and political philosophies that emphasize the Anti-authoritarianism, anti-authoritarian and libertarian aspects of Marxism. Early currents of libertarian Marxism such as

left communism

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices held by Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions ...

emerged in opposition to Marxism–Leninism.

Libertarian Marxism is often critical of Reformism, reformist positions such as those held by Social democracy, social democrats. Libertarian Marxist currents often draw from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels' later works, specifically the and ''The Civil War in France''; emphasizing the Marxist belief in the ability of the working class to forge its own destiny without the need for

state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...