Columbus Delano (June 4, 1809 – October 23, 1896) was an American lawyer, rancher, banker,

statesman, and a member of the prominent

Delano family

In the United States, members of the Delano family include U.S. presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Ulysses S. Grant and Calvin Coolidge, astronaut Alan B. Shepard, and writer Laura Ingalls Wilder. Its progenitor is Phili ...

. Forced to live on his own at an early age, Delano struggled to become a self-made man. Delano was elected U.S. Congressman from Ohio, serving two full terms and one partial one. Prior to the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Delano was a

National Republican and then a

Whig; as a Whig, he was identified with the faction of the party that opposed the spread of slavery into the Western territories. He became a

Republican when the party was founded as the major anti-slavery party after the demise of the Whigs in the 1850s. During

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

Delano advocated federal protection of African-Americans' civil rights, and argued that the former Confederate states should be administered by the federal government, but not as part of the United States until they met the requirements for readmission to the Union.

Delano served as President

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

's

Secretary of the Interior during a time of rapid Westward expansionism, and contended with conflicts between

Native tribes and

White American

White Americans (sometimes also called Caucasian Americans) are Americans who identify as white people. In a more official sense, the United States Census Bureau, which collects demographic data on Americans, defines "white" as " person having ...

settlers. He was instrumental in the establishment of America's first national park, having supervised the first federally funded scientific expedition into

Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U ...

in 1871, and becoming America's first national park overseer in 1872. In 1874, Delano requested that Congress protect Yellowstone through the creation of a federally funded administrative agency, the first Secretary of the Interior to request such preservation of a nationally important site.

Believing that the communal, collective, and nomadic lifestyles of Native American tribes led to war and impoverishment, Delano argued that the most humane Indian policy was to force tribes onto

small reservations in the

Indian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

, ceding their land to the United States, and assimilating them into white culture. The goal was for Indian tribes to be independent of federal funding. To compel the Native tribes to move to reservations, Delano supported the slaughter to the near extinction of the vast

buffalo herds outside of

Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U ...

, which were essential to the maintenance of the

Plains Indians

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nations peoples who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) of North ...

' way of life.

Concerning government reform, Delano defied Grant's 1872 executive order to implement the first

Civil Service Commission

A civil service commission (also known as a Public Service Commission) is a government agency or public body that is established by the constitution, or by the legislature, to regulate the employment and working conditions of civil servants, overse ...

's recommendations. With the exception of

Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U ...

, the

spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a rewar ...

and corruption permeated throughout the Interior Department during his tenure, and Grant requested Delano's resignation in 1875; he left office with his reputation damaged. Delano remained a

spoils man at a time when reformer demands for a federal merit system were gaining support. Delano returned to Ohio to practice law, tend to his business interests, and raise livestock; he did not return to politics and died in 1896.

Delano was traditionally viewed as a 19th-century American "major mover and shaker." However, historians have strongly criticized Delano's weak oversight of the Interior, allowing rampant corruption, and for his treatment of Native Americans and endorsement of the Plains Indian

bison

A bison (: bison) is a large bovine in the genus ''Bison'' (from Greek, meaning 'wild ox') within the tribe Bovini. Two extant taxon, extant and numerous extinction, extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American ...

slaughter. Yellowstone is considered Delano's greatest achievement, where bison and other wildlife were legally protected. He was viewed as an effective first administrator of America's first national park. While in office, Delano was an outspoken supporter of black American rights and an opponent of the Ku Klux Klan.

Early life, education, and political career

Columbus Delano was born in

Shoreham, Vermont

Shoreham is a New England town, town in Addison County, Vermont, United States. The population was 1,260 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census.

Geography

Shoreham is located in western Addison County along the shore of Lake Champlain. T ...

, on June 4, 1809,

[The Biographical Dictionary of America]

''Delano, Columbus''

p. 225 the son of James Delano and Lucinda Bateman. The

Delano family

In the United States, members of the Delano family include U.S. presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Ulysses S. Grant and Calvin Coolidge, astronaut Alan B. Shepard, and writer Laura Ingalls Wilder. Its progenitor is Phili ...

was of French ancestry; its first representative in America, Philip Delano, voyaged from Holland in 1621 on the ''

Fortune

Fortune may refer to:

General

* Fortuna or Fortune, the Roman goddess of luck

* Luck

* Wealth

* Fate

* Fortune, a prediction made in fortune-telling

* Fortune, in a fortune cookie

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''The Fortune'' (19 ...

'', the sister ship of the ''

Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English sailing ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, reac ...

''. Delano's father died in 1815 when Delano was six years old, and his family was put under the care of his uncle Luther Bateman. In 1817 the family moved to

Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is the former residence and plantation of George Washington, a Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States, and his wife, Martha. An American landmar ...

in

Knox County, Ohio, where Delano resided for the rest of his life.

[ Delano was raised primarily by Luther Bateman, who died in 1817.][ After an elementary education Delano worked in a woolen mill in ]Lexington, Ohio

Lexington is a village (United States)#Ohio, village along the Clear Fork River in Troy Township, Richland County, Ohio, Troy Township and Washington Township, Richland County, Ohio, Washington Township in Richland County, Ohio, Richland County ...

, and at other manual laboring jobs, becoming largely self-sufficient while still a teenager.[

After beginning self-directed legal studies, Delano formally trained with Mount Vernon attorney Hosmer Curtis from 1830 to 1831, and he attained admission to the bar in 1831.][ Delano became active in politics as a National Republican, and later as a Whig,][The Biographical Dictionary of America]

''Delano, Columbus''

p. 226 and in 1834 he won election as Prosecuting Attorney for Knox County.

Marriage and family

On July 14, 1834, Delano married Elizabeth Leavenworth of Mount Vernon, the daughter of M. Martin Leavenworth and Clara Sherman Leavenworth. Their children included daughter Elizabeth (1838–1904), who was the wife of Reverend John G. Ames of Washington, DC, and son John Sherman Delano (1841–1896), a businessman who also worked with his father at the Department of the Interior.

Delano and Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

were distant cousins; they had great-great-grandparents in common.

United States Representative (1845–1847)

In 1844, Delano was elected to the

In 1844, Delano was elected to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

after appearing on the ballot as a replacement for Samuel White Jr., who had died after winning the Whig nomination. He went on to defeat Democrat Caleb J. McNulty by only 12 votes, 9,297 to 9,285.

Tenure

Delano served in the 29th Congress, (March 4, 1845—March 3, 1847), and was a member of the Committee on Invalid Pensions. He also gave a speech denouncing the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

which earned him national recognition as an opponent of the conflict.

Campaign for governor

Delano did not run for reelection in 1846, instead campaigning for the 1848 Whig nomination for Governor of Ohio

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the type of political region or polity, a ''governor'' ma ...

. He lost to Seabury Ford by two votes at the January 1848 party convention; Ford went on to defeat Democrat John B. Weller in a close general election, and served one term. Delano subsequently became involved in several business ventures; in 1850 he set up a successful Wall Street

Wall Street is a street in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs eight city blocks between Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway in the west and South Street (Manhattan), South Str ...

banking partnership, ''Delano, Dunlevy, & Company'', which specialized in railroad bonds; it included a branch office in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

and operated for five years. In addition, Delano became a successful sheep

Sheep (: sheep) or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are a domesticated, ruminant mammal typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to d ...

rancher, and served as president of the National Association of Wool Growers and the Ohio Wool Growers Association. He was also active in other businesses; he was president of the Springfield, Mount Vernon & Pittsburgh Railroad, and an original incorporator of the First National Bank of Mount Vernon, of which he later became president.

Republican Party and the Civil War

With the demise of the Whigs, Columbus Delano joined the new Republican Party. Delano was a delegate to the Chicago Convention

The Convention on International Civil Aviation, also known as the Chicago Convention, established the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a specialized agency of the United Nations charged with coordinating international air trav ...

in 1860, and he seconded the nomination of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

for president. Delano actively campaigned for Lincoln, who won the presidency. The following year Delano served as Commissary-General of Ohio, on the staff of Governor William Dennison Jr., and aided in raising and equipping troops for the Union Army at the start of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. In 1862 Delano was a candidate for the United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

seat held by Benjamin Wade. With Republicans in control of the Ohio General Assembly

The Ohio General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Ohio. It consists of the 99-member Ohio House of Representatives and the 33-member Ohio Senate. Both houses of the General Assembly meet at the Ohio Statehouse in Colu ...

, winning their nomination was tantamount to election by the full legislature. Delano was nearly successful, losing the nomination to Wade by only two votes. In 1863, Delano served in the Ohio House of Representatives

The Ohio House of Representatives is the lower house of the Ohio General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Ohio; the other house of the bicameral legislature being the Ohio Senate.

The House of Representatives first met in ...

and played a notable role in shepherding the passage of legislation in support of the Union war effort. Delano served as Chairman of the Judicial Committee and settled the matter of the right of soldiers to vote. Delano served as Chairman of the Ohio delegation that attended the Baltimore Convention. Lincoln was successfully nominated for a second term of office.

Reconstruction Era

Return to Congress

Delano was again elected to the U.S. House in 1864, and he served in the 39th Congress (March 4, 1865—March 3, 1867). During this term, Delano was chairman of the House Committee on Claims. Delano appeared to lose his bid for reelection in 1866, but successfully contested the election of George W. Morgan. After unseating Morgan, Delano served for the remainder of the 40th Congress, June 3, 1868—March 3, 1869. After the Civil War Delano supported Radical Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

, believing that the South was in chaos and that federal involvement in the Southern states, including the army, was necessary to keep the peace. He did not run for reelection in 1868.

Reconstruction speech (1867)

In September 1867, Delano made a speech on Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

in Eaton, Ohio

Eaton is a city in and the county seat of Preble County, Ohio, United States, approximately west of Dayton. The population was 8,375 at the 2020 census, down 0.4% from the population of 8,407 at the 2010 census.

History

Eaton was founded a ...

, in which he said that President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

did not have the constitutional authority to establish civil government in the former Confederate states. Delano argued that Congress, not the president, "was required to establish civil governments in all the states." In Delano's view, Johnson and Southern Democrats, who had previously supported the Confederacy, were conspiring to overthrow Congress by undermining its authority to make laws concerning Southern Reconstruction. As proof, Delano cited Johnson's September 1866 Swing Around the Circle speech, in which Johnson said the national legislature was a "pretended Congress". In addition, Delano believed Johnson was conspiring to remove Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

as head of the army because of Grant's support for Congressional Reconstruction. As a result, Delano advocated impeaching Johnson and removing him from office, and argued that Grant should be protected by Congress from any attempt by Johnson to remove him. Unknown to Delano, on August 11, 1867, Grant had agreed to accept Johnson's offer to serve as interim Secretary of War, while simultaneously remaining general of the army. Under the provisions of the Tenure of Office Act, the appointment would be temporary until the U.S. Senate returned to session in January 1868, and either ratified or prohibited Stanton's removal. Johnson and Grant agreed to Grant's temporary appointment despite explicitly admitting that they disagreed on Reconstruction policy.

Commissioner of Internal Revenue

Delano remained active in politics and supported Grant for president in 1868. When Grant became president in March 1869, he appointed Delano Commissioner of Internal Revenue

The Commissioner of Internal Revenue is the head of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), an agency within the United States Department of the Treasury.

The office of Commissioner was created by United States Congress, Congress as part of the Reven ...

; Delano served from March 11, 1869, to October 31, 1870. As commissioner, Delano tried with mixed success to collect federal revenue on alcohol and tobacco products manufactured in Indian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

; these items could be produced for sale tax-free within the territory, but manufacturers routinely sold them in adjacent states without paying the taxes. He also proved unwilling or unable to cope with the frauds of the Whiskey Ring

The Whiskey Ring took place from 1871 to 1876 centering in St. Louis during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. The ring was an American scandal, broken in May 1875, involving the diversion of tax revenues in a conspiracy among government agent ...

; despite having received warnings of corruption including bribery of federal officials and failure to pay taxes, Delano took little or no action. The department did attempt to prevent the illegal manufacture and sale of whiskey in other areas; on January 31, 1870, an Internal Revenue raid in Georgia captured 18 illicit whiskey stills and their operators. The Whiskey Ring was finally stopped in 1875 during Grant's second term by Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin Bristow. The ring leader, John McDonald was an acquaintance of President Grant and had requested from him a political appointment as superintending inspector of internal revenue in St. Louis. Grant then directed Delano to make the appointment. McDonald was convicted of fraud and theft and served 17 months in prison. In all, the investigation of the Whiskey Ring resulted in 110 convictions. Grant's private secretary, Orville E. Babcock was implicated, but acquitted at trial after Grant provided written testimony on his behalf. Additionally, Delano was cleared of involvement in another scandal in which Babcock was implicated, the Gold Ring, which was triggered when two New York financiers attempted to corner the gold market on September 24, 1869. Daniel Butterfield, the Assistant Treasurer of the United States

The treasurer of the United States is an officer in the United States Department of the Treasury who serves as the custodian and trustee of the federal government's collateral assets and the supervisor of the department's currency and coinage pr ...

, and Grant's brother in law Abel Corbin were also implicated; Butterfield was forced to resign in October. Delano's reputation for personal honesty was not in question, which was an asset when Grant needed to nominate a new Secretary of the Interior in 1870.

Secretary of the Interior

United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general is the head of the United States Department of Justice and serves as the chief law enforcement officer of the Federal government of the United States, federal government. The attorney general acts as the princi ...

Ebenezer R. Hoar and Secretary of the Interior Jacob D. Cox resigned in 1870 because of Grant's decision to overrule them on the issue of the McGarrahan Claims; speculator William McGarrahan claimed title to a tract of mining land in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, as did the New Idria Mining Company. Grant wanted no executive branch action taken, considering both claims to be fraudulent; Cox and Hoar disagreed and decided in favor of New Idria, which prompted Grant to request their resignations.

Grant appointed Delano to succeed Cox at the Interior Department; he served from November 1, 1870, until resigning on October 19, 1875. During Delano's tenure, the Interior Department was the largest bureaucracy in the federal government, including numerous patronage positions. Running the department required knowledge of dissimilar duties, and the ability to master complex details. During Delano's time as secretary, he faced several critical issues and his department was rapidly expanding; despite the challenges he served longer in the job than any other 19th-century incumbent. Delano aligned himself with Grant's private secretary Orville Babcock and Secretary of Navy George M. Robeson. Delano rejected the civil service reforms of his predecessor Cox and reverted the Interior to the spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a rewar ...

.

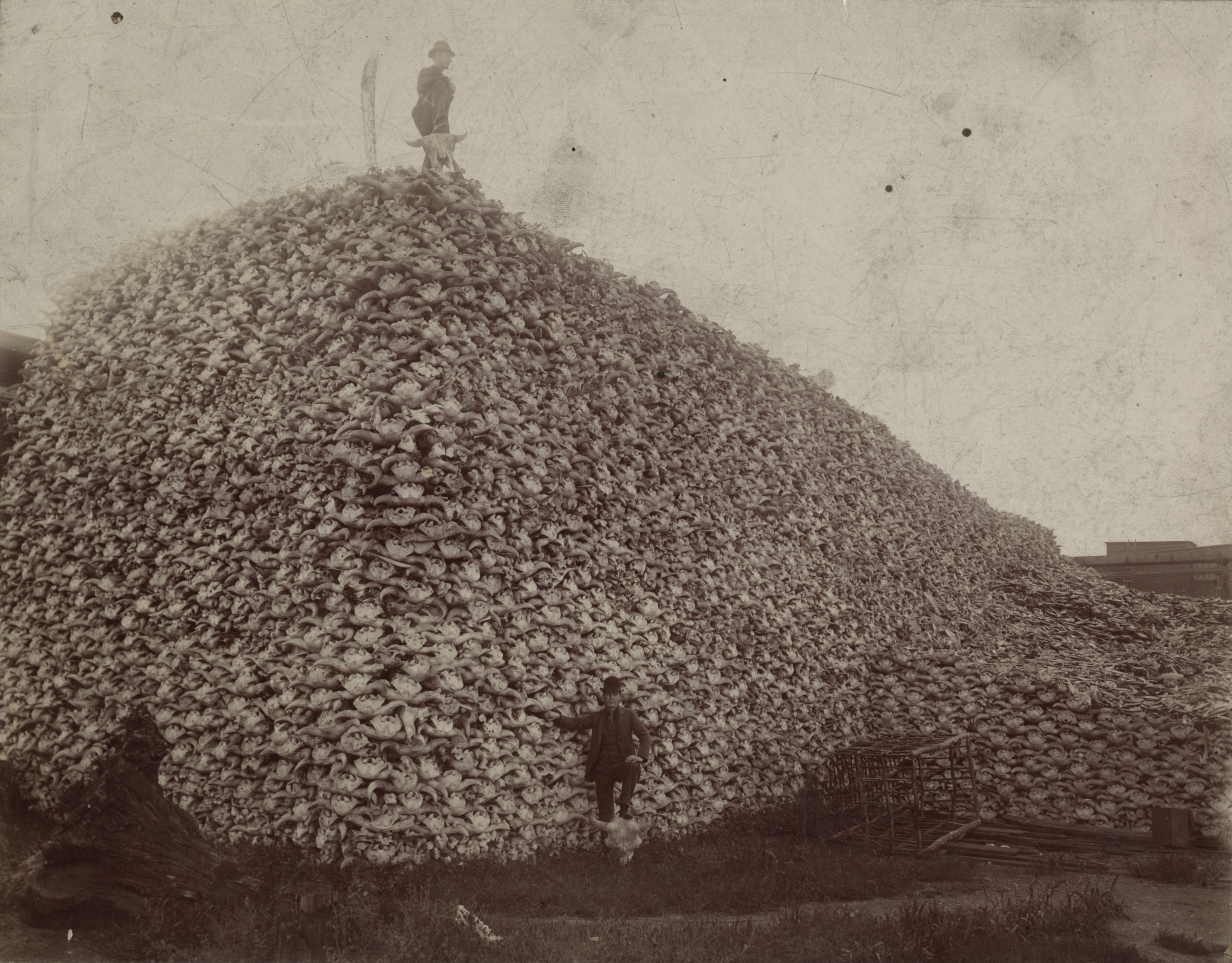

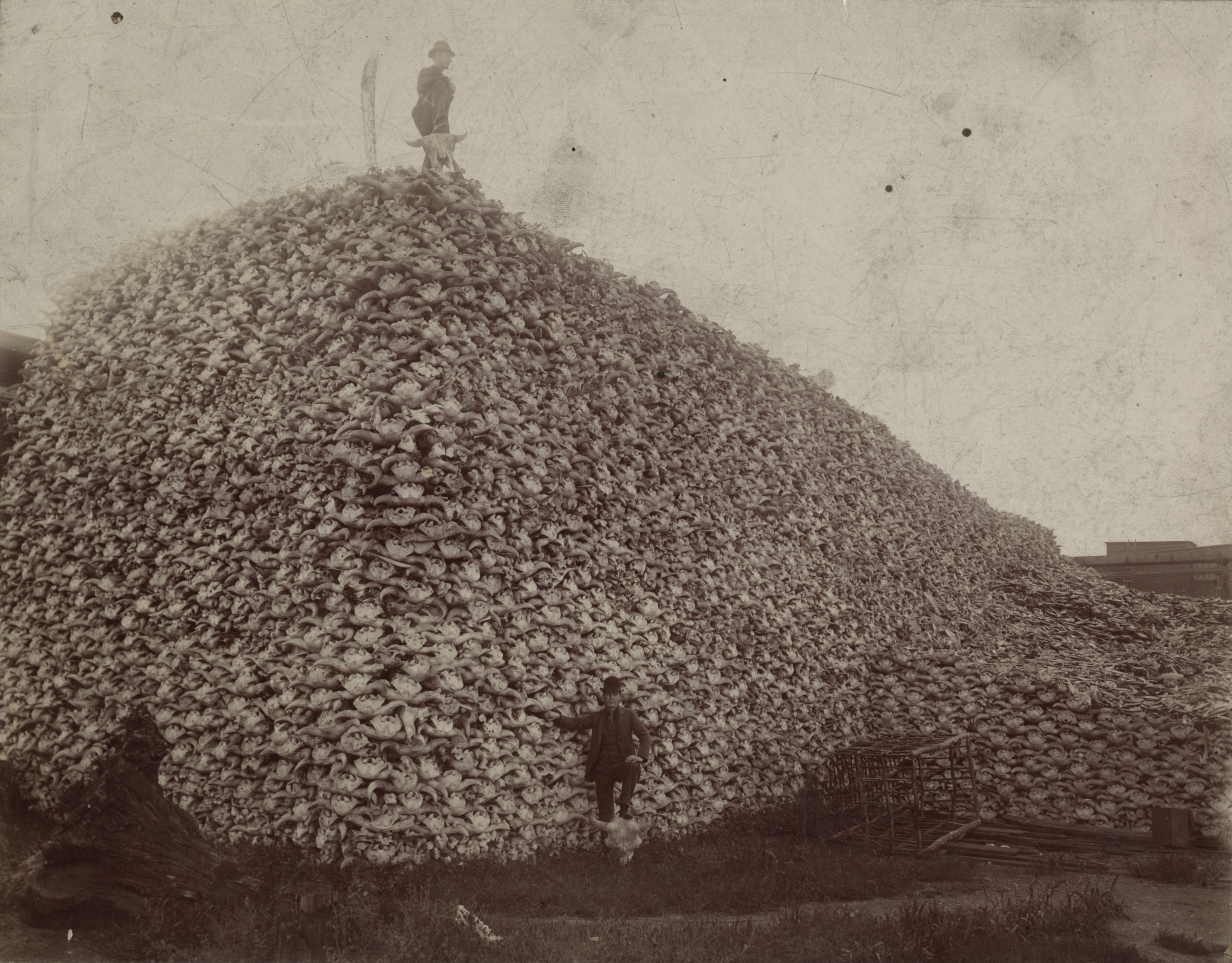

Bison slaughter (1870s)

During the Civil War, Union generals practiced a "scorched earth" campaign against Confederate infrastructure that destroyed its vital food supplies, which aided in bringing about the Union's victory. During the late 1860s and early 1870s U.S. Army officers

During the Civil War, Union generals practiced a "scorched earth" campaign against Confederate infrastructure that destroyed its vital food supplies, which aided in bringing about the Union's victory. During the late 1860s and early 1870s U.S. Army officers William T. Sherman

William is a masculine given name of Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern era. It is ...

, Richard Dodge, and Secretary of the Interior Delano adopted a similar strategy against Native Americans in the west, whose primary food supply was free-roaming bison

A bison (: bison) is a large bovine in the genus ''Bison'' (from Greek, meaning 'wild ox') within the tribe Bovini. Two extant taxon, extant and numerous extinction, extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American ...

. Dodge said in 1867, "Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone." Delano said in an 1872 annual report, "The rapid disappearance of the game isonfrom the former hunting-grounds must operate largely in favor of our efforts to confine the Indians to smaller areas, and compel them to abandon their nomadic customs."

Much of the destruction of bison was done by private, for-profit buffalo hunters; this policy allowed the slaughter of millions of bison on the American plains, forcing Indians to move to and remain on their reservations. The few free-roaming bison left in Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U ...

were protected from poaching by a federal law passed in 1872; during Delano's tenure, mounting criticism by the public forced Congress to pass legislation that would stop the bison slaughter on the plains. Grant vetoed the legislation in 1874, accepting that the bison slaughter was accomplishing the goal of pacifying the Indians. From 1872 to 1874 the Indians killed approximately 1,215,000 bison as part of providing for their food, shelter, and other basic needs; American hunters slaughtered an estimated 4,374,000 bison, reducing the population to the point that it could not reproduce normally and continue to sustain the Indians.

Apache massacre and peace (1871–1872)

On April 30, 1871, Tucson

Tucson (; ; ) is a city in Pima County, Arizona, United States, and its county seat. It is the second-most populous city in Arizona, behind Phoenix, Arizona, Phoenix, with a population of 542,630 in the 2020 United States census. The Tucson ...

townspeople organized a militia, consisting of 6 Americans, 48 Mexicans and 94 Tohono O'odham Indians, which massacred 144 members of an Apache

The Apache ( ) are several Southern Athabaskan language-speaking peoples of the Southwestern United States, Southwest, the Southern Plains and Northern Mexico. They are linguistically related to the Navajo. They migrated from the Athabascan ho ...

Indian settlement at Camp Grant,[Michno, pp. 248, 249] mostly women and children. Twenty-eight children were kidnapped by the militia and held as ransom for the Apache warriors, who were not present at the time of the massacre.[ The people of Tucson drew national attention by the scale of their activity, resulting in Eastern philanthropists and President Grant denouncing their actions. Arizona citizens, however, believed the killings were justified and claimed that Apache warriors had killed mail runners and settlers near Tucson.][ President Grant sent Major General ]George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer who served in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. He is best known for commanding U.S. forces in the Geronimo Campaign, 1886 campaign that ...

to keep the peace in Arizona; many Apaches had joined the U.S. military for protection.[

On November 10, 1871, Delano advocated Grant that Apaches be given new reservation land in Arizona and New Mexico, following the recommendation of Indian Peace Commissioner Vincent Colyer to find them a location where they could be protected from attacks by white settlers.][New York Times (November 11, 1871), Sec. Delano's Letter Relating to the Apaches] Delano advocated that all Apaches be put on reservations including young men and warriors, who were forming raiding parties, rather than just their old men and women.[ Grant sent Major General ]Oliver Otis Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men again ...

to Arizona to help resolve the issue; Howard organized a peace conference with Apache leader Eskiminzin in May 1872 at Camp Grant. Howard also negotiated the release of six of the captive Apache children.[ In December 1872, the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, a permanent settlement, was established at the junction of the San Carlos and Gila Rivers, the location having been agreed upon by Howard and Eskiminzin.][ In October 1872, Howard also made a separate peace treaty with the Apache leader Cochise, who settled on the ]Chiricahua

Chiricahua ( ) is a band of Apache Native Americans.

Based in the Southern Plains and Southwestern United States, the Chiricahua historically shared a common area, language, customs, and intertwined family relations with their fellow Apaches. ...

reservation.

Akerman feud (1871)

In June 1871 Grant's Attorney General Amos T. Akerman denied land and bond grants to the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad is a Railroad classes, Class I freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pacific is the second largest railroad in the United Stat ...

, a company connected to the Crédit Mobilier scandal. Ackerman's anti-railroad rulings were protested by railroad financiers Collis P. Huntington and Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who founded the Gould family, Gould business dynasty. He is generally identified as one of the Robber baron (industrialist), robber bar ...

. Akerman was also instrumental in prosecuting the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

in the South and protecting African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

civil rights. Railroad interests and African-American civil rights had been priorities for the Republican Party; on behalf of Huntington and Gould, Delano twice asked Akerman to change rulings that had gone against the Union Pacific, and both times Akerman refused. Delano then complained to Grant and suggested that Akerman should be removed. Grant agreed, and named former Oregon Senator George H. Williams as Akerman's replacement; Williams was seen as more favorable to railroad interests. On the issue of curtailing the Klan prosecutions, according to historian William S. McFeely, " th Akerman's departure on January 10, 1872, went any hope that the Republican party would develop as a national party of true racial equality."

Yellowstone (1871–1872)

In 1871, Delano organized America's first federally funded scientific expedition into

In 1871, Delano organized America's first federally funded scientific expedition into Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U ...

, which was headed by U.S. Geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden.[Greater Yellowstone]

A Brief History of Science in Yellowstone

/ref> Delano gave specific instructions for Hayden to make a geographical map of the area and to make astronomical

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest include ...

and barometric observations. Delano stated that Hayden's expedition was directed to "...secure as much information as possible, both scientific and practical...give your attention to the geological, mineralogical, zoological, botanical, and agricultural resources of the country."[ Delano also ordered Hayden to gather information on Native American tribes who lived in the area. Hayden's expedition was outfitted by an extensive scientific team that included two ]botanist

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

s, a meteorologist

A meteorologist is a scientist who studies and works in the field of meteorology aiming to understand or predict Earth's atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric phenomena including the weather. Those who study meteorological phenomena are meteorologists ...

, a zoologist

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the structure, embryology, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct, and how they interact with their ecosystems. Zoology is one ...

, an ornithologist

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

, a mineralogist

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical mineralogy, optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifact (archaeology), artifacts. Specific s ...

, a topographer

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the landforms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary scienc ...

, an artist, a photographer, a physician, hunter

Hunting is the human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, and killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to obtain the animal's body for meat and useful animal products ( fur/ hide, bone/tusks, ...

s, mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey, and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two ...

teams and ambulances, and a support staff.

On March 1, 1872

On March 1, 1872 Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

signed the ''Organic Act'', incorporating Hayden's findings and discoveries and creating Yellowstone, the world's first national park. The law provided that the Secretary of the Interior exercise "exclusive control" over Yellowstone; As Delano was the incumbent, this made him the first overseer of the first national park in the world. The poaching of fish and wildlife, including bison, was forbidden, and Delano was authorized to preserve the "natural curiosities and wonders" found inside the park. Delano was now in charge of millions of acres of land, however, he was not provided any funding to care for it. Instead, he was given the power to grant 10-year leases in order to raise money to pay for maintaining the park. As soon as the park was created, Delano was inundated by requests for hotel concessions, and he also had to determine the control and use of existing facilities in the park's northern section.

Delano appointed N. P. Langford the first Supervisor of Yellowstone in 1872; Langford banned private toll roads and submitted a plan to build and maintain a park road system free to the public, but Congress refused to fund it. Congress also refused to give Langford a stipend, so he had to supplement his livelihood by working as a banker. In 1874 Lanford requested that Delano petition Congress for appropriations to protect the park from poachers, unlicensed privateers, and trespassers. Delano agreed and demanded Congress appropriate $100,000 to set up a federal park agency to administer and protect the park for the public, and also asked for an increase in the terms of the concession leases from 10 to 20 years. The proposal was turned down; it was not until April 1877, during the Rutherford B. Hayes administration, that Congress appropriated one-tenth of Delano's request, $10,000, (~$ in ) without any federal protection agency for the park.

Defied Civil Service Executive order (1871–1874)

In March 1871, Grant signed into law Congressional legislation that established the United States Civil Service Commission, designed to create reform rules and to regulate and reduce corruption in the federal workforce. Implementation of the rules was left to the discretion of the President. Grant appointed New York reformer William Curtis to chair the commission. The Commission reported that appointments and promotions would be controlled by examiners, and each federal department would create a board of examiners, while political assessments would be abolished. Grant ordered the implementation of the rules to be effective on January 1, 1872. Grant dissolved the commission in 1874 after Congress refused to make the Commission rules permanent, and refused to provide permanent funding for the commission. Congressional interest in civil service reform would remain dormant until 1883.

Under Article 12 of Grant's executive order, Land Office and Pension agent applicants in the Department of Interior were to be approved by a board of examiners. Delano, however, betrayed Grant and defied the order. Grant made no response. The Interior Department's varied and diverse responsibilities increased at a rapid rate and became a source of numerous administrative problems. For the department head, controlling the bureaus and shaping policy was a daunting task; Delano argued that the complexities of the department made implementing civil service reform impractical. Under Delano's tenure, corruption permeated the whole department, including bogus agents in the Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States List of United States federal agencies, federal agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of the Interior. It is responsible for im ...

and thieving clerks in the Patent Office

A patent office is a governmental or intergovernmental organization which controls the issue of patents. In other words, "patent offices are government bodies that may grant a patent or reject the patent application based on whether the applicati ...

. Delano ultimately resigned because of evidence that surveying contracts had been awarded to companies in which his son John, the chief clerk of the department, and Orvil (or Orville) Grant, the president's brother, had ownership interests; this was more or less permissible by the standards of the day, but to reform-minded individuals, including the editors of the '' New-York Tribune'' and other newspapers, it represented a conflict of interest and breach of the public trust.

Supported Ku Klux Klan prosecutions (1872)

To bolster the Reconstruction Acts and the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth constitutional amendments, Grant signed in 1870 Congressional legislation that created the Justice Department. To fight the outrages in the South by the Ku Klux Klan, Grant signed several laws known as the Enforcement Acts in 1870 and 1871. In May 1871, Grant ordered federal troops to help U.S. Marshals in arresting Klansmen. Grant's second Attorney General Amos T. Akerman, a former Confederate soldier, knew of the outrages of the Klan and was zealous in prosecuting white Southerners who terrorized their black neighbors. That October, on Akerman's recommendation, Grant suspended ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

'' in part of South Carolina and sent federal troops there to enforce the law. After prosecutions by Akerman and his replacement, George Henry Williams, the Klan's power collapsed; by 1872, elections in the South saw African Americans voting in record numbers.

In a campaign speech supporting President Grant's reelection bid in Raleigh, North Carolina

Raleigh ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of North Carolina. It is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, second-most populous city in the state (after Charlotte, North Carolina, Charlotte) ...

, on July 24, 1872, Delano spoke out in favor of prosecutions of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

. Delano argued that the Congressional Reconstruction Acts had been passed to "rescue order and government out of the chaos and confusion" that came from the Civil War. This included the enfranchisement of African Americans, most of them former slaves, who had been set "forever free" as a result of the war. Delano stated that if freedom meant anything it was that African Americans "should stand equal before the law and have a voice in legislation." According to Delano, southerners who rejected Republican Reconstruction opted for a subversive war against African Americans and white Republicans, including the formation of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

. Delano said the Ku Klux Klan had in fourteen North Carolina counties killed 18 people and cruelly whipped 315 Republicans who had done nothing wrong. Delano said that evidence presented in prosecuting Klan members in the federal courts proved the "barbarity and treason" of the Ku Klux Klan. Grant ended up winning North Carolina and many other Southern states.

Defined Indian policy (1873)

In 1873, Delano formally defined the methods to be used in attaining the goals of Grant's policy toward the Native Americans. Grant's ultimate goal was to convert the Indians to Christianity and assimilate them into the white culture in order to prepare them for full U.S. Citizenship; these fundamental principles continued to influence Indian Peace policy for the rest of the 19th Century. According to Delano, relocating the Indians to reservations was of primary importance, since this would supposedly protect them from the violence of white settlers as whites moved onto lands previously held by Native Americans. In addition, Christian organizations and missionaries operating on these reservations could "civilize" the Native Americans, in line with the widespread belief (including Delano's) that allowing the Indians to continue to practice their own culture would lead to their destruction. In Delano's view, his actions would accomplish Grant's goal by facilitating Indian assimilation into white culture.

Black Hills take over (1875)

Under the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, the Oglala Sioux had been given a huge reservation including the Black Hills in what is now South Dakota. The Black Hills were the site of Sioux sacred religious rituals and spiritual ceremonies. Following the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "L ...

the country was desperate for new wealth. In 1874 rumors spread of gold being discovered in the Black Hills by George Custer's recent expedition. Grant sent the expedition, hoping to find gold in order to support his species currency policy; Delano opposed the move, believing travel through and eventual occupation of hunting grounds violated the Treaty of Fort Laramie and could lead to an Indian war. Delano told Grant that a "general war with the Sioux would be deplorable. It would undo the good already accomplished by our efforts for peaceable relations." Whites immediately flocked to the area in search of gold; in 1875, Congress appropriated $25,000 (~$ in ) for the purchase of the Black Hills, hoping that a cash payment would assuage the Sioux and prevent war.

In mid-May 1875, Red Cloud, Chief of the Oglala Lakota

The Oglala (pronounced , meaning 'to scatter one's own' in Lakota language, Lakota) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota people, Dakota, make up the Sioux, Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A ...

(Sioux), and other Indian tribal leaders were brought to Washington D.C. to negotiate the sale of the Black Hills. The Sioux believed the amount offered by Congress was too low; recognizing that they would eventually lose the Black Hills, Red Cloud decided to negotiate and told Delano they would sign away the Black Hills if $25,000 in cash was first drawn from the Treasury Department, to ensure that the Sioux would be paid. Delano had no intention of giving Red Cloud cash, but rather a receipt for $25,000 from the Treasury and additional presents purchased at a later date and distributed to members of the tribe. Red Cloud insisted that he wanted the $25,000 in cash at the signing, which would be taken home and divided among the members of the tribe.

Delano warned Grant that a war would likely break out if negotiations were not successful. When negotiations broke down, Grant was brought into the process to bargain directly with Red Cloud. Grant told Red Cloud that the Black Hills had no buffalo, so it would benefit the Indians to accept payment because they would at least receive something of value in consideration for signing away valueless hunting rights. He also informed Red Cloud that whites were going to take over the Black Hills anyway, so it would be best not to leave empty-handed. Concerned that they would not be paid if they signed an agreement first, Red Cloud asked Grant to withdraw the money from the Treasury and hold it until after the signing. Grant refused and walked out, telling Red Cloud he had to sign over the Black Hills before any payment was made. On June 4, Delano offered Red Cloud an additional $25,000 in appropriations, but Red Cloud refused.

With Red Cloud's refusal, Delano reluctantly let the Indians take the unsigned agreement back to their tribal agencies for further discussion among the members of the tribe, with final terms and signatures to be negotiated later by an appointed commission. The failure of the Washington, D.C. negotiations to produce an agreement was lampooned in the June 19 edition of '' Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper''. Upon their return to Sioux country, Red Cloud and other Lakota leaders finally signed away their hunting rights to the Black Hills under Article 11 of the Treaty of Fort Laramie in exchange for the original $25,000 Congressional appropriation. Another group of Sioux chiefs, including

Delano warned Grant that a war would likely break out if negotiations were not successful. When negotiations broke down, Grant was brought into the process to bargain directly with Red Cloud. Grant told Red Cloud that the Black Hills had no buffalo, so it would benefit the Indians to accept payment because they would at least receive something of value in consideration for signing away valueless hunting rights. He also informed Red Cloud that whites were going to take over the Black Hills anyway, so it would be best not to leave empty-handed. Concerned that they would not be paid if they signed an agreement first, Red Cloud asked Grant to withdraw the money from the Treasury and hold it until after the signing. Grant refused and walked out, telling Red Cloud he had to sign over the Black Hills before any payment was made. On June 4, Delano offered Red Cloud an additional $25,000 in appropriations, but Red Cloud refused.

With Red Cloud's refusal, Delano reluctantly let the Indians take the unsigned agreement back to their tribal agencies for further discussion among the members of the tribe, with final terms and signatures to be negotiated later by an appointed commission. The failure of the Washington, D.C. negotiations to produce an agreement was lampooned in the June 19 edition of '' Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper''. Upon their return to Sioux country, Red Cloud and other Lakota leaders finally signed away their hunting rights to the Black Hills under Article 11 of the Treaty of Fort Laramie in exchange for the original $25,000 Congressional appropriation. Another group of Sioux chiefs, including Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota people, Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against Federal government of the United States, United States government policies. Sitting Bull was killed by Indian ...

and Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse ( , ; – September 5, 1877) was a Lakota people, Lakota war leader of the Oglala band. He took up arms against the United States federal government to fight against encroachment by White Americans, White American settlers on Nativ ...

, challenged Red Cloud's authority and started the armed resistance about which Delano had warned Grant. This challenge to Red Cloud's authority combined with Lakota unhappiness over white encroachment into the Black Hills resulted in the Great Sioux War

The Great Sioux War of 1876, also known as the Black Hills War, was a series of battles and negotiations that occurred in 1876 and 1877 in an alliance of Lakota people, Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne against the United States. The cause of t ...

, which started in February 1876.

Resignation and corruption (1875)

In 1875, Delano's reputation for personal honesty came under increasing scrutiny as revelations of corruption in the Grant administration continued to be the subject of investigations and media revelations. Although Delano himself was not known to be personally corrupt, his tenure was shadowed by controversy, while fraud prevailed in his Interior Department. There were accusations of an "Indian Ring" and corrupt agents who exploited Native American people. Westerners unhappy with Delano's rulings on land grants and other issues accused Delano's son John, an employee of the Interior Department, of corruption, bribery, and fraud in the Wyoming Territory

The Territory of Wyoming was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 25, 1868, until July 10, 1890, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Wyoming. Cheyenne was the territorial capital. The ...

.

=Surveyor General Ring

=

The '' New-York Tribune'' reported that John Delano was profiteering through Interior's Office of the Surveyor-General by accepting partnerships in Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

surveying contracts without having been trained in surveying or map-making, and without providing any meaningful contribution to the fulfillment of the contracts; the obvious implication was John Delano had taken extortion money from illicit contract agreements. In March 1875, the former chief clerk of the Surveyor's Office, L. C. Stevens, wrote to Benjamin Bristow, Grant's Secretary of the Treasury, stating that Surveyor General Silas Reed had made several corrupt contracts which financially benefited John Delano. Stevens also said both Reed and John Delano had blackmailed five deputy surveyors for $5,000. According to Stevens, Reed and Delano had coerced the deputy surveyors to pay John Delano before he would release the Interior Department warrants for land the deputy surveyors had sold to prospective settlers. Governor Edward M. McCook of the Colorado Territory

The Territory of Colorado was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from February 28, 1861, until August 1, 1876, when it was admitted to the Union as the 38th State of Colorado.

The territory was organized ...

, claimed that John Delano had accepted a $1,200 bribe from a Colorado banker, Jerome B. Chaffee, to secure land patents from the Department of Interior. More damaging was Stevens' charge that Columbus Delano knew and approved of what Reed had done for John Delano.

In addition to Delano's son, Grant's brother Orvil was paid for surveying services in the Wyoming Territory

The Territory of Wyoming was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 25, 1868, until July 10, 1890, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Wyoming. Cheyenne was the territorial capital. The ...

, although Orvil did no work. The chief clerk of the Cheyenne branch of the federal Surveying Office testified before Congress concerning Orvil. When asked whether Orvil did any work in the Wyoming Territory, the chief clerk said, "No, sir, I do not think he was ever in the territory."

=Indian Ring

=

In July 1875, Delano was rumored to know that Orvil Grant, the president's brother, had received Indian trading posts, that were a corrupt source of lucrative kickbacks, from the

In July 1875, Delano was rumored to know that Orvil Grant, the president's brother, had received Indian trading posts, that were a corrupt source of lucrative kickbacks, from the sutler

A sutler or victualer is a civilian merchant who sells provisions to an army in the field, in camp, or in quarters. Sutlers sold wares from the back of a wagon or a temporary tent, traveling with an army or to remote military outposts. Sutler wa ...

, at the expense of the Indians and soldiers. The higher the sale price on goods, that the Indians and soldiers would pay, the higher the profits. Even the sale of rifles to hostile Indian tribes was allowed, to make more money. The profits were split and sent to the other sutler partners.

Delano was rumored to have threatened Grant at Long Branch that he would expose Orvil to the public when Delano's resignation was enforced. He told Grant that he would quietly leave office after Congressional Indian fraud investigations were complete. In February 1876, the ''New York Herald'' reported that Orvil made money in the Sioux country by "starving the squaws and children." Orvil testified before Congress that Grant had influenced the War Department to get him traderships. Orvil received rights to operate four trading posts, then set up "partners" who kicked back half their profits to Orvil. Though Orvil claimed Grant had not known of the kickbacks, he expressed no remorse for his corruption, and his testimony left Grant embarrassed.

The kingpin of this Indian Ring was not Delano, but Secretary of War William W. Belknap, who was given legal authority by Congress in 1870 to appoint sutlers to traderships at Army posts near Indian reservations, which were controlled by Interior. Belknap, who had awarded Orvil Grant the four traderships, took advantage of the law to personally profit by arranging an illicit partnership at Fort Sill between his wife Carrie, Caleb P. Marsh, and sutler John S. Evans. After Carrie's death, Belknap married her sister Amanda, who continued the illicit tradership arrangement. Belknap's household received as much as $20,000 in illegal profits (nearly $500,000 in 2021), which Belknap needed in order to finance the lavish Washington D.C. entertainment lifestyle expected of cabinet members and other prominent political figures.

Aware that the U.S. House was investigating him, on March 2, 1876, Belknap visited Grant and immediately resigned. The House continued its inquiry and found him guilty of five articles of impeachment. Grant's attorney general placed Belknap under house arrest during his U.S. Senate trial. Though most senators believed the evidence of Belknap's corruption, enough believed they lacked the jurisdiction to punish Belknap because he was no longer in office to acquit him. Despite escaping conviction, Belknap's reputation was so marred that he never returned to political office.

=Resignation

=

Both Bristow and Secretary of State Hamilton Fish demanded that Grant fire Delano. Grant declined, telling Fish, "If Delano were now to resign, it would be retreating under fire and be accepted as an admission of the charges." The controversy did not abate; by mid-August, it became clear that Delano could not remain in office; Delano offered his resignation and Grant accepted, but Grant did not make it public. Grant finally announced his acceptance of Delano's resignation on October 19, 1875, after Bristow threatened to resign if Delano was not replaced. Grant replaced Delano with Zachariah Chandler, who quickly initiated civil service and other reforms in the Department of the Interior. Delano's administration was investigated by Congress, Chandler, and a special presidential commission; his personal conduct was exonerated, but his reputation as an honest, capable administrator was damaged, and Delano never again ran for office or served in an appointed one. In April 1876, ''The Committee on the Expenditures in the Interior Department'' confirmed that Reed had set up an illicit

Both Bristow and Secretary of State Hamilton Fish demanded that Grant fire Delano. Grant declined, telling Fish, "If Delano were now to resign, it would be retreating under fire and be accepted as an admission of the charges." The controversy did not abate; by mid-August, it became clear that Delano could not remain in office; Delano offered his resignation and Grant accepted, but Grant did not make it public. Grant finally announced his acceptance of Delano's resignation on October 19, 1875, after Bristow threatened to resign if Delano was not replaced. Grant replaced Delano with Zachariah Chandler, who quickly initiated civil service and other reforms in the Department of the Interior. Delano's administration was investigated by Congress, Chandler, and a special presidential commission; his personal conduct was exonerated, but his reputation as an honest, capable administrator was damaged, and Delano never again ran for office or served in an appointed one. In April 1876, ''The Committee on the Expenditures in the Interior Department'' confirmed that Reed had set up an illicit slush fund

A slush fund is a fund or account used for miscellaneous income and expenses, particularly when these are corrupt or illegal. Such funds may be kept hidden and maintained separately from money that is used for legitimate purposes. Slush funds m ...

for John Delano's financial benefit and that Delano thanked Reed while also telling him "to be careful to do nothing that would have the semblance of wrong."

=Delano's defense

=

On September 26, 1875, Delano submitted to Grant a letter defending his tenure at the Department of the Interior; in essence, he argued that the size and complexity of his department made it difficult to manage effectively. Delano stated that he had resigned because he intended to return to his business and domestic concerns in Ohio. He indicated that his duties as Secretary of the Interior were "laborious, difficult, and delicate" because he was required to supervise five disparate bureaus or offices: United States General Land Office

The General Land Office (GLO) was an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the United States government responsible for Public domain (land), public domain lands in the United States. It was created in 1812 ...

; Indian; Pensions

A pension (; ) is a fund into which amounts are paid regularly during an individual's working career, and from which periodic payments are made to support the person's retirement from work. A pension may be either a "defined benefit plan", wher ...

; Patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

; and Education

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education als ...

, in addition to "a mass of miscellaneous business unknown to any except those connected to the public service."

Delano also reminded Grant that the Land Office dealt with complex railroad land grants, as well as issues resolving land titles in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, Arizona

Arizona is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States, sharing the Four Corners region of the western United States with Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. It also borders Nevada to the nort ...

and New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

, because those areas had previously been under Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

's and then Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

's jurisdiction. In addition, the Indian Bureau dealt with many "intricate, delicate, and vexatious questions" growing out of previous Indian treaties. Delano further informed Grant that when he had to decide issues between competing claimants, those he ruled against often gave false and misleading statements rather than accept their loss, which was to Delano's detriment. Delano concluded by claiming a successful tenure, informing Grant that the Interior Department "has never been in a more prosperous or better condition than it now is."

=Chandler reforms

=

Delano's successor, Zachariah Chandler, did not complain about his departmental duties and immediately investigated allegations of corruption. Chandler found things differently than Delano's explanations to Grant and decided the department needed major reforming. During his first month in office, he fired all the clerks in one room of the Patent Office; he noted that every desk was vacant, and concluded that the employees were either involved in corruption or lacked the integrity to reform the department. Almost twenty employees were found to be entirely fictitious; they had been created by a profiteering ring to defraud the government by falsely receiving pay for work that was not performed. Chandler also fired unqualified clerks who profiteered by hiring out their work to lower-paid replacements and pocketing the salary difference.

In addition, Chandler simplified Patent Office rules, making patents easier to obtain and reducing the cost for applicants. In December 1875, Chandler banned persons known as "Indian Attorneys", whose claims to represent Native Americans in Washington were questionable. He found the Bureau of Indian Affairs to be the most corrupt and replaced its commissioner and chief clerk. In addition to Indian Affairs, Chandler also investigated the Pension Bureau. This review resulted in the identification and removal of numerous fraudulent pensions, which saved the federal government hundreds of thousands of dollars. Chandler also revoked as many as 800 fraudulent land grants that had been approved during Delano's tenure.

Delano's successor, Zachariah Chandler, did not complain about his departmental duties and immediately investigated allegations of corruption. Chandler found things differently than Delano's explanations to Grant and decided the department needed major reforming. During his first month in office, he fired all the clerks in one room of the Patent Office; he noted that every desk was vacant, and concluded that the employees were either involved in corruption or lacked the integrity to reform the department. Almost twenty employees were found to be entirely fictitious; they had been created by a profiteering ring to defraud the government by falsely receiving pay for work that was not performed. Chandler also fired unqualified clerks who profiteered by hiring out their work to lower-paid replacements and pocketing the salary difference.

In addition, Chandler simplified Patent Office rules, making patents easier to obtain and reducing the cost for applicants. In December 1875, Chandler banned persons known as "Indian Attorneys", whose claims to represent Native Americans in Washington were questionable. He found the Bureau of Indian Affairs to be the most corrupt and replaced its commissioner and chief clerk. In addition to Indian Affairs, Chandler also investigated the Pension Bureau. This review resulted in the identification and removal of numerous fraudulent pensions, which saved the federal government hundreds of thousands of dollars. Chandler also revoked as many as 800 fraudulent land grants that had been approved during Delano's tenure.

Later life and career

On his resignation from Grant's cabinet, Delano returned to Mount Vernon where for the next twenty years he served as president of the First National Bank of Mount Vernon. He was a longtime trustee of Kenyon College

Kenyon College ( ) is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Gambier, Ohio, United States. It was founded in 1824 by Episcopal Bishop Philander Chase. It is the oldest private instituti ...

, which awarded him the honorary degree

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

of LL.D.; among his charitable and civic donations was his endowment of Kenyon's Delano Hall; this building was in use until it was destroyed by a fire in 1906. His "Lakehome" mansion, built in 1871 at the outskirts of Mount Vernon, is now part of Mount Vernon Nazarene University.

On April 3, 1880, John W. Wright, a judge from Indiana, was convicted at trial of having assaulted Delano on a Washington, D.C. street corner on October 12, 1877. Wright, who had been an Indian Agent in the Interior Department while Delano was secretary, had been convicted of fraud and blamed Delano. On the day of the assault he was in the company of Walter H. Smith, formerly solicitor of the Department of the Interior; Wright was accused of provoking a fight by questioning Delano's honesty as Secretary of the Interior and then striking Delano with his walking stick. Wright claimed that Delano had been verbally harassing him and that he then felt compelled to defend himself. Delano did not sustain serious injuries; Wright's defense was weakened by witness testimony that after the assault, he claimed credit for it, and stated that he would have continued if passers-by had not intervened. Wright was sentenced to 30 days in jail and fined $1,000. On April 8, 1880, President Rutherford B. Hayes pardoned Wright, with his release from custody conditional upon the payment of the fine.

On December 3, 1889, Delano was elected president of the National Wool Growers Association, a lobbying group organized to advocate for tariff protection of the national wool industry. The association had been formed in 1865, and became more active in the 1880s as a response to the decline in domestic wool production; wool growers faced increasing overseas competition and had gone from 50 million sheep producing wool in 1883 to 40 million in 1888.

Death

Delano died on October 23, 1896; he was interred at Mount Vernon's Mound View Cemetery, Lot 42, Section 16, Grave 4. Delano's death was sudden and unexpected, and took place at his "Lakehome" residence near Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is the former residence and plantation of George Washington, a Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States, and his wife, Martha. An American landmar ...

, at 11:00 AM. Delano's wife had fallen and broken her hip on October 20, an accident unrelated to Delano's death. She died in August 1897.

Historical legacy

Delano's career prior to becoming Secretary of the Interior was not known for any scandals, nor has he been implicated in the Crédit Mobilier scandal. Historians, however, are critical of Delano's overall tenure as Secretary of the Interior, especially for his loose anti-reform administrative style and for allowing corruption to permeate the department. As such, Delano was at odds with many of Grant's other Cabinet members, including Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, Secretary of Treasury Benjamin Bristow, and Attorney General Amos T. Akerman. The corruption under Delano in the Bureau of Indian Affairs, an agency within the Interior Department, in particular eventually led to the end of the agency being part of the political appointee and career civil servant systems and pushed it toward bureaucratization. Delano later defended his reputation by saying that the Interior Department was difficult to manage due to its expanding size and its many offices with disparate functions.

Indian advancement

In March 1869, President Grant appointed Ely S. Parker, a Seneca Indian, to commissioner of Indian Affairs serving under both Interior secretaries Cox and Delano. Although there was resistance to his appointment, the Senate confirmed Parker could legally hold office, and he was confirmed by the Senate. During Parker's tenure, lasting until August 1871, Indian wars decreased significantly from 101 in 1869 to 58 in 1870.

In 2021, some 145 years after Delano left office in 1875, the position of secretary of the interior was first filled by a Native American. On December 17, 2020, president-elect Joe Biden

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. (born November 20, 1942) is an American politician who was the 46th president of the United States from 2021 to 2025. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as the 47th vice p ...

announced that he would nominate Deb Haaland to serve as secretary of the interior. She was confirmed by the Senate on March 15, 2021, by a vote of 51–40.vice president

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

and Kaw Nation citizen Charles Curtis

Charles Curtis (January 25, 1860 – February 8, 1936) was the 31st vice president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 under President Herbert Hoover. He was the Senate Majority Leader from 1924 to 1929. An enrolled member of the Kaw Natio ...

.

Bison slaughter and Indian suppression

Delano has also received criticism for allowing millions of bison

A bison (: bison) is a large bovine in the genus ''Bison'' (from Greek, meaning 'wild ox') within the tribe Bovini. Two extant taxon, extant and numerous extinction, extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American ...

to be slaughtered, with the exception of Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U ...

, in order to compel the Indians to move to and remain on their reservations, a policy approved by President Grant and the U.S. Army. The demise of the bison herds during Delano's tenure led to the destruction of the Plains Indian culture, including their economy, cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

, and religion. Without the bison, the Plains Indians could not resist late 19th-century expansionism, including the development of the railroads in the American West. This policy led to more restrictive measures against Native Americans in the 1880s and 1890s, including the banning of medicine making, polygamy, bride payments, and the Sun Dance.

Yellowstone and bison recovery

Delano was the first Secretary of the Interior to be in charge of

Delano was the first Secretary of the Interior to be in charge of Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U ...

, America's and the world's first national park. The charges of misconduct and lax management made during Delano's tenure at the Interior did not include the new park, the management of which was seen as a success. Among its features, it outlawed poaching wildlife and served as a haven for small numbers of free-roaming bison, left after the slaughter of the great herds that, with the exception of Yellowstone, Delano had fully supported. On August 25, 1916, Congress created the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

to federally protect and administer Yellowstone and other national parks; Delano had proposed the creation of the agency in 1874. Yellowstone today generates around 4 million visitors per year.

By 1902, poachers

Poaching is the illegal hunting or capturing of wild animals, usually associated with land use rights.

Poaching was once performed by impoverished peasants for subsistence purposes and to supplement meager diets. It was set against the hunti ...

had illegally killed and reduced Yellowstone bison

A bison (: bison) is a large bovine in the genus ''Bison'' (from Greek, meaning 'wild ox') within the tribe Bovini. Two extant taxon, extant and numerous extinction, extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American ...

herd size to about two dozen animals. The U.S. Army, which administered Yellowstone, prior to the creation of the National Park Service, took over and protected the last remaining bison from further poaching.Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...