Collaboration In German-occupied Ukraine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ukrainian collaboration with Nazi Germany took place during the

The elimination of

The elimination of  Reinforced by religious prejudice, antisemitism turned violent in the first days of the German attack on the Soviet Union. Some Ukrainians derived nationalist resentment from the belief that the Jews had worked for Polish landlords. The

Reinforced by religious prejudice, antisemitism turned violent in the first days of the German attack on the Soviet Union. Some Ukrainians derived nationalist resentment from the belief that the Jews had worked for Polish landlords. The

On 28 April 1943, the German Governor of the

On 28 April 1943, the German Governor of the

occupation of Poland

Occupation commonly refers to:

*Occupation (human activity), or job, one's role in society, often a regular activity performed for payment

*Occupation (protest), political demonstration by holding public or symbolic spaces

*Military occupation, th ...

and the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

, USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

By September 1941, the German-occupied territory of Ukraine was divided between two new German administrative units, the District of Galicia

The District of Galicia (, , ) was a World War II administrative unit of the General Government created by Nazi Germany on 1 August 1941 after the start of Operation Barbarossa, based loosely within the borders of the ancient Principality o ...

of the Nazi General Government

The General Government (, ; ; ), formally the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (), was a German zone of occupation established after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, Slovak Republic (1939–1945), Slovakia and the Soviet ...

and the Reichskommissariat Ukraine

The ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' (RKU; ) was an administrative entity of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories of Nazi Germany from 1941 to 1944. It served as the German civilian occupation regime in the Ukrainian SSR, and ...

. Some Ukrainians chose to resist and fight the German occupation forces and joined either the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

or the irregular partisan

Partisan(s) or The Partisan(s) may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

** Francs-tireurs et partisans, communist-led French anti-fascist resistance against Nazi Germany during WWII

** Ital ...

units conducting guerrilla warfare against the Germans. Most Ukrainians, especially in western Ukraine

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine (, ) refers to the western territories of Ukraine. There is no universally accepted definition of the territory's boundaries, but the contemporary Ukrainian administrative regions ( oblasts) of Chernivtsi, I ...

, had little to no loyalty toward the Soviet Union, which had been repressively occupying eastern Ukraine

Eastern Ukraine or East Ukraine (; ) is primarily the territory of Ukraine east of the Dnipro (or Dnieper) river, particularly Kharkiv, Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts (provinces). Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts are often also regarded as ...

in the interwar years and had overseen a famine in the early 1930s called the Holodomor

The Holodomor, also known as the Ukrainian Famine, was a mass famine in Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians. The Holodomor was part of the wider Soviet famine of 1930–193 ...

that killed millions of Ukrainians. Some who worked with or for the Nazis against the Allied forces Ukrainian nationalists

Ukrainian nationalism (, ) is the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The origins of modern Ukrainian nationalism emerge during the Cossack uprising against the Poli ...

hoped that enthusiastic collaboration would enable them to re-establish an independent state. Many were involved in a series of war crimes and crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

, including the Holocaust in Ukraine

The Holocaust saw the systematic mass murder of Jews in the '' Reichskommissariat Ukraine'', the General Government, the Crimean General Government and some areas which were located to the east of ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' (all of those ar ...

, and the massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

The Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia (; ) were carried out in Occupation of Poland (1939–1945), German-occupied Poland by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), with the support of parts of the local Ukrainians, Ukrainian popu ...

.

Ukrainians, including ethnic minorities like Russians, Tatars and others, who collaborated with the Nazi Germany did so in various ways including participating in the local administration, in German-supervised auxiliary police, Schutzmannschaft

The ''Schutzmannschaft'', or Auxiliary Police ( "protection team"; plural: ''Schutzmannschaften'', abbreviated as ''Schuma'') was the collaborationist auxiliary police of native policemen serving in those areas of the Soviet Union and the Balti ...

, in the German military, or as guards in the concentration camp

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploitati ...

s.

Background

Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, the ruler of the USSR, and Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

, the ruler of Nazi Germany, both demanded territory from their immediate neighbour, the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 7 October 1918 and 6 October 1939. The state was established in the final stage of World War I ...

. The Soviet invasion of Poland

The Soviet invasion of Poland was a military conflict by the Soviet Union without a formal declaration of war. On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Second Polish Republic, Poland from the east, 16 days after Nazi Germany invaded Polan ...

in 1939 brought together Ukrainians of the USSR and Ukrainians of what was then Eastern Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

(Kresy

Eastern Borderlands (), often simply Borderlands (, ) was a historical region of the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic. The term was coined during the interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural and extensively multi-ethnic with ...

), under a single Soviet banner. In the territories of Poland invaded by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, the size of the Ukrainian minority became negligible and was gathered mostly around UCC (), formed in Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

.

Less than two years later, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union. The German Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

began on June 22, 1941. Operation Barbarossa brought together native Ukrainians of the USSR and the prewar territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union

Seventeen days after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, which marked the beginning of the Second World War, the Soviet Union entered the eastern regions of Poland (known as the ) and annexed territories totalling with a population of 13,299 ...

. By September the occupied territory was divided between two new German administrative units: to the southwest, the District of Galicia

The District of Galicia (, , ) was a World War II administrative unit of the General Government created by Nazi Germany on 1 August 1941 after the start of Operation Barbarossa, based loosely within the borders of the ancient Principality o ...

of the Nazi General Government

The General Government (, ; ; ), formally the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (), was a German zone of occupation established after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, Slovak Republic (1939–1945), Slovakia and the Soviet ...

, and the northeast, Reichskommissariat Ukraine

The ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' (RKU; ) was an administrative entity of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories of Nazi Germany from 1941 to 1944. It served as the German civilian occupation regime in the Ukrainian SSR, and ...

, which stretched all the way to Donbas

The Donbas (, ; ) or Donbass ( ) is a historical, cultural, and economic region in eastern Ukraine. The majority of the Donbas is occupied by Russia as a result of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

The word ''Donbas'' is a portmanteau formed fr ...

by 1943.

Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( , ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a German high-ranking SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust. He held the rank of SS-. Many historians regard Heydrich ...

noted in a report dated July 9, 1941 "a fundamental difference between the former Polish and Russian ovietterritories. In the former Polish region, the Soviet regime was seen as enemy rule... Hence the German troops were greeted by the Polish as well as the White Ruthenia

White Ruthenia (; ; ; ; ) is one of the historical divisions of Kievan Rus' according to the color scheme, which also includes Black and Red Ruthenia. In the Late Middle Ages and Early Modern period, the name White Ruthenia was characterized by i ...

n population eaning Ukrainian and Belarusianfor the most part, at least, as liberators or with friendly neutrality... The situation in the current occupied White Ruthenian areas of the re-1939USSR has a completely different basis."

Ukrainian nationalist partisan leader Taras Bulba-Borovets

Taras Dmytrovych Borovets (; March 9, 1908 – May 15, 1981) was a Ukrainian leader and Nazi collaborator of the Ukrainian National Army during World War II. He is better known as Taras Bulba-Borovets after his ''nom de guerre'' ''Taras Bulba'' ...

gathered a force of 3,000 in summer 1941 to help the Wehrmacht fight the Red Army. In September 1942, Borovets entered into negotiations with the Soviet partisans of Dmitry Medvedev

Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev (born 14 September 1965) is a Russian politician and lawyer who has served as Deputy Chairman of the Security Council of Russia since 2020. Medvedev was also President of Russia between 2008 and 2012 and Prime Mini ...

. They tried to attract him to the struggle against the Germans but could not reach an agreement. Borovets refused to obey the Soviet command structure and feared German retaliation against Ukrainian civilians. Still, until the spring of 1943 neutrality was maintained between the Borovets detachments and the Soviet partisans. Parallel to the negotiations with the Soviets, Borovets continued to try to reach an agreement with the Germans. In November 1942, he met with Obersturmbannführer

__NOTOC__

''Obersturmbannführer'' (Senior Assault-unit Leader; ; short: ''Ostubaf'') was a paramilitary rank in the German Nazi Party ( NSDAP) which was used by the SA (''Sturmabteilung'') and the SS (''Schutzstaffel''). The rank of ' was juni ...

Puts, the head of the security service of Volhynia and Podolia

Podolia or Podillia is a historic region in Eastern Europe located in the west-central and southwestern parts of Ukraine and northeastern Moldova (i.e. northern Transnistria).

Podolia is bordered by the Dniester River and Boh River. It features ...

general district.

In November 1943, during negotiations with the Germans, Borovets was arrested by the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

in Warsaw and incarcerated in Sachsenhausen concentration camp

Sachsenhausen () or Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg was a German Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, used from 1936 until April 1945, shortly before the defeat of Nazi Germany in May later that year. It mainly held political prisoners t ...

. In the autumn of 1944, the Nazis, looking for Ukrainian support in a war they were by then losing, freed Borovets. He was forced to change his nom de guerre to ''Kononenko'' and under this name he led the formation of a Ukrainian special forces detachment of around 50 men under the ''Waffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

''. This detachment was to be dropped in the rear of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

for guerrilla warfare. Those plans never came to fruition.

At the end of the war Hitler's Ukrainian nationalist allies demanded transfers away from the Eastern Front so that they could surrender to Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

rather than Soviet forces. Borovets' detachment surrendered to the Allies on May 10, 1945, and was interned in Rimini

Rimini ( , ; or ; ) is a city in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy.

Sprawling along the Adriatic Sea, Rimini is situated at a strategically-important north-south passage along the coast at the southern tip of the Po Valley. It is ...

, Italy. Because of the fluid nature of these allegiances, historian Alfred Rieber has emphasized that labels such as "collaborators" and "resistance" have been rendered useless in describing the actual loyalty of these groups. However, in the newly annexed portions of western Ukraine, there was little to no loyalty towards The Soviet Union, whose Red Army had seized Ukraine during the Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939.

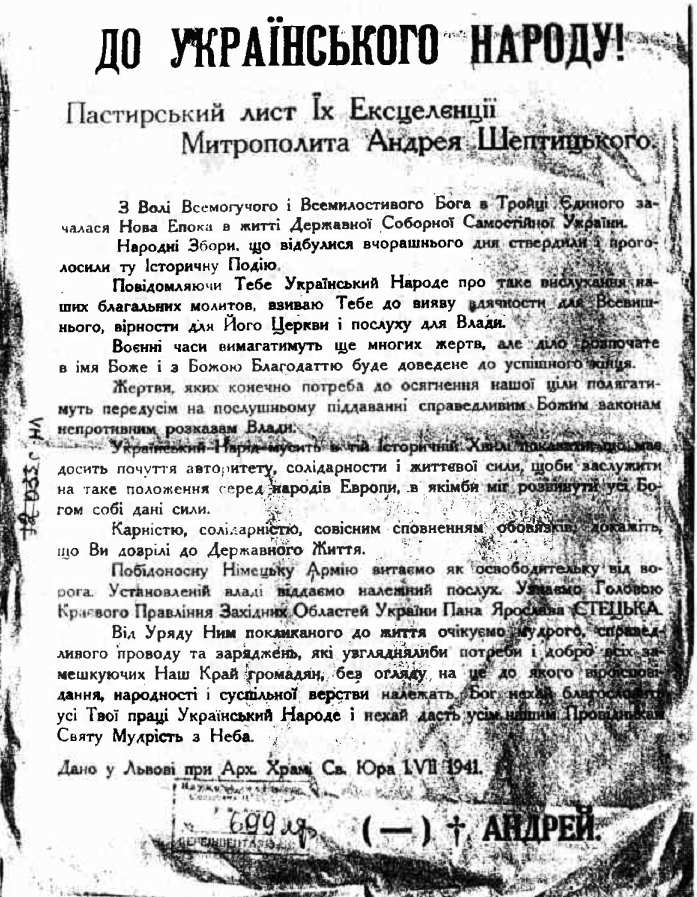

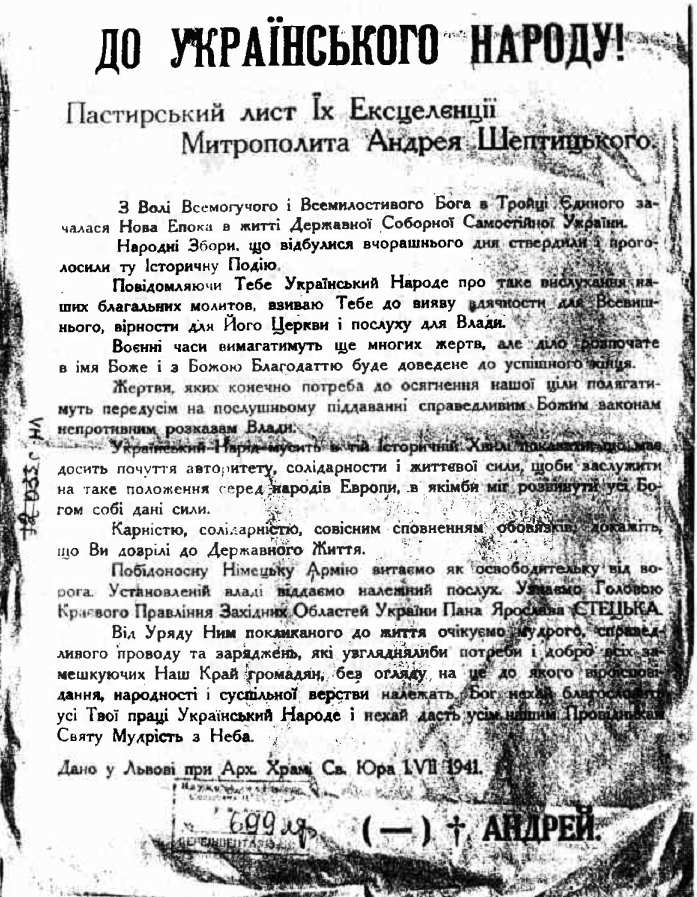

Occupation

Nationalists in western Ukraine hoped that their efforts would enable them to re-establish an independent state later on. For example, on the eve of Operation' Barbarossa, as many as 4,000 Ukrainians, operating underWehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

orders, sought to cause disruption behind Soviet lines. After the capture of Lviv

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

, a highly-contentious and strategically important city with a significant Ukrainian minority, OUN leaders proclaimed a new Ukrainian State on June 30, 1941, and encouraged loyalty to the new regime in the hope that the Germans would support it. In 1939, during the German-Polish War, the OUN was "a faithful German auxiliary".John A. Armstrong, ''Collaborationism in World War II: The Integral Nationalist Variant in Eastern Europe'', The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Sep., 1968), p. 409.

Despite an initial warm reaction to the idea of an independent Ukraine (see Ukrainian national government (1941)

The Ukrainian national government () was a brief self-proclaimed Ukrainian government during the German invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Ax ...

), the Nazi administration had other ideas, particularly the Lebensraum

(, ) is a German concept of expansionism and Völkisch movement, ''Völkisch'' nationalism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' beca ...

programme and the total ' Aryanisation' of the population. It played the Slavic nations against one another. OUN initially carried out attacks on Polish villages to try to exterminate Polish populations or expel Polish enclaves from what the OUN fighters perceived as Ukrainian territory. This culminated in the mass killings of Polish families in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.

According to Timothy Snyder

Timothy David Snyder (born August 18, 1969) is an American historian specializing in the history of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and the Holocaust. He is on leave from his position as the Richard C. Levin, Richar ...

, "something that is never said, because it's inconvenient for precisely everyone, is that more Ukrainian Communists collaborated with the Germans, than did Ukrainian nationalists." Snyder also points out that very many of those who collaborated with the German occupation also collaborated with the Soviet policies in the 1930s.

Holocaust

Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

during the Holocaust in Ukraine

The Holocaust saw the systematic mass murder of Jews in the '' Reichskommissariat Ukraine'', the General Government, the Crimean General Government and some areas which were located to the east of ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' (all of those ar ...

started within a few days of the beginning of the Nazi occupation. The Ukrainian Auxiliary Police

The Ukrainian Auxiliary Police (; ) was the official title of the local police formation (a type of hilfspolizei) set up by Nazi Germany during World War II in Eastern Galicia and '' Reichskommissariat Ukraine'', shortly after the German occupati ...

, which formed mid August 1941, assisted by Einsatzgruppen

(, ; also 'task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the imp ...

C, and Police battalions rounded up Jews and undesirables for the Babi Yar

Babi Yar () or Babyn Yar () is a ravine in the Ukraine, Ukrainian capital Kyiv and a site of massacres carried out by Nazi Germany's forces during Eastern Front (World War II), its campaign against the Soviet Union in World War II. The first and ...

massacre, as well as other later massacres in cities and towns of modern-day Ukraine, such as Kolky, Stepan

Stepan (; ; ) is a rural settlement in Sarny Raion (district) of Rivne Oblast (province) in western Ukraine. Its population was 4,073 as of the 2001 Ukrainian Census. Current population:

The settlement is located in the historic Volhynia regi ...

, Lviv

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

, Lutsk

Lutsk (, ; see #Names and etymology, below for other names) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of Volyn Oblast and the administrative center of Lutsk Raion within the oblast. Lutsk has a populati ...

, and Zhytomyr

Zhytomyr ( ; see #Names, below for other names) is a city in the north of the western half of Ukraine. It is the Capital city, administrative center of Zhytomyr Oblast (Oblast, province), as well as the administrative center of the surrounding ...

.

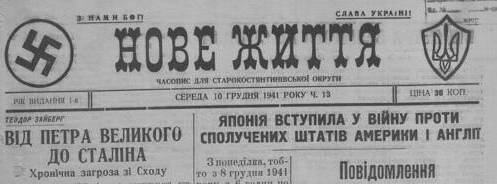

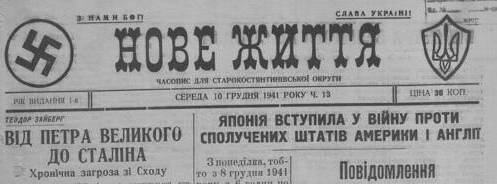

During this period, on 1 September 1941, the Nazi-sponsored Ukrainian newspaper ''Volhyn'' wrote, in an article titled Zavoiovuimo misto" (Let's Conquer the City):

"All elements that reside in our land, whether they are Jews or Poles, must be eradicated. We are at this very moment resolvingthe Jewish question The Jewish question was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century Europe that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other " national questions", dealt with the civil, legal, national, ..., and this resolution is part of the plan for the Reich's total reorganization of Europe.", "The empty space that will be created, must immediately and irrevocable be filled by the real owners and masters of this land, the Ukrainian people".

Reinforced by religious prejudice, antisemitism turned violent in the first days of the German attack on the Soviet Union. Some Ukrainians derived nationalist resentment from the belief that the Jews had worked for Polish landlords. The

Reinforced by religious prejudice, antisemitism turned violent in the first days of the German attack on the Soviet Union. Some Ukrainians derived nationalist resentment from the belief that the Jews had worked for Polish landlords. The NKVD prisoner massacres

The NKVD prisoner massacres were a series of mass executions of political prisoners carried out by the NKVD, the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs of the Soviet Union, across Eastern Europe, primarily in Poland, Ukraine, the Baltic states ...

by the Soviet secret police while they retreated eastward were blamed on Jews. The antisemitic canard

Antisemitic tropes, also known as antisemitic canards or antisemitic libels, are " sensational reports, misrepresentations or fabrications" about Jews as an ethnicity or Judaism as a religion.

Since the 2nd century, malicious allegations of ...

of Jewish Bolshevism

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an antisemitic and anti-communist conspiracy theory that claims that the Russian Revolution of 1917 was a Jewish plot and that Jews controlled the Soviet Union and international communist moveme ...

provided justification for the revenge killings by the ultranationalist Ukrainian People's Militia

Ukrainian People's Militia () or the Ukrainian National Militia, was a paramilitary formation created by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) in the General Government territory of occupied Poland and later in the Reichskommissariat Uk ...

, which accompanied German ''Einsatzgruppen

(, ; also 'task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the imp ...

'' moving east. In Boryslav

Boryslav (, ; ) is a city located on the Tysmenytsia (river), Tysmenytsia (a tributary of the Dniester), in Drohobych Raion, Lviv Oblast (Oblast, region) of western Ukraine. It hosts the administration of Boryslav urban hromada, one of the hroma ...

(prewar Borysław, Poland, population 41,500), the SS commander gave an enraged crowd, which had seen bodies of men murdered by NKVD and laid out in the town square, 24 hours to act as they wished against Polish Jews

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Jews, Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the long pe ...

, who were forced to clean the dead bodies and to dance and then were killed by beating with axes, pipes etc. The same type of mass murders took place in Brzezany. During Lviv pogroms

The Lviv pogroms were the consecutive pogroms and massacres of Jews in June and July 1941 in the city of Lwów in German-occupied Eastern Poland/Western Ukraine (now Lviv, Ukraine). The massacres were perpetrated by Ukrainian nationalists (s ...

, 7,000 Jews were murdered by Ukrainian nationalists, led by the Ukrainian People's Militia

Ukrainian People's Militia () or the Ukrainian National Militia, was a paramilitary formation created by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) in the General Government territory of occupied Poland and later in the Reichskommissariat Uk ...

. As late as 1945, Ukrainian militants were still rounding up and murdering Jews.

While some of the collaborators were civilians, others were given a choice to enlist for paramilitary service beginning in September 1941 from the Soviet prisoner-of-war camps because of ongoing close relations with the Ukrainian ''Hilfsverwaltung''. In total, over 5,000 native Ukrainian soldiers of the Red Army signed up for training with the SS at a special Trawniki training camp to assist with the Final Solution

The Final Solution or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question was a plan orchestrated by Nazi Germany during World War II for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews. The "Final Solution to the Jewish question" was the official ...

. Another 1,000 defected during field operations. Trawniki men

During World War II, Trawniki men (; ) were Eastern European Nazi collaborators, consisting of either volunteers or recruits from Prisoner of war, prisoner-of-war camps set up by Nazi Germany for Red Army, Soviet Red Army soldiers captured in the ...

took a major part in the Nazi plan to exterminate European Jews during Operation Reinhard

Operation Reinhard or Operation Reinhardt ( or ; also or ) was the codename of the secret Nazi Germany, German plan in World War II to exterminate History of the Jews in Poland, Polish Jews in the General Government district of German-occupied ...

. They served at all extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe, primarily in occupied Poland, during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocau ...

s and played an important role in the annihilation of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the 1943 act of Jewish resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto in German-occupied Poland during World War II to oppose Nazi Germany's final effort to transport the remaining ghetto population to the gas chambers of the ...

(see the Stroop Report

The Stroop Report is an official report prepared by General Jürgen Stroop for the SS chief Heinrich Himmler, recounting the German suppression of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the liquidation of the ghetto in the spring of 1943. Originally t ...

) and the Białystok Ghetto Uprising

Białystok is the largest city in northeastern Poland and the capital of the Podlaskie Voivodeship. It is the tenth-largest city in Poland, second in terms of population density, and thirteenth in area.

Białystok is located in the Białystok ...

among other ghetto insurgencies. The men who were dispatched to death camps and Jewish ghettos as guards were never fully trusted and so were always overseen by ''Volksdeutsche

In Nazi Germany, Nazi German terminology, () were "people whose language and culture had Germans, German origins but who did not hold German citizenship." The term is the nominalised plural of ''wikt:volksdeutsch, volksdeutsch'', with denoting ...

''. Occasionally, along with the prisoners they were guarding, they would kill their commanders in the process of attempting to defect.

In May 2006, the Ukrainian newspaper ''Ukraine Christian News'' commented, "Carrying out the massacre was the Einsatzgruppe C, supported by members of a Waffen-SS battalion and units of the Ukrainian auxiliary police, under the general command of Friedrich Jeckeln

Friedrich August Jeckeln (2 February 1895 – 3 February 1946) was a German Nazi Party member, police official and SS-'' Obergruppenführer'' during the Nazi era. He served as a Higher SS and Police Leader in Germany and in the occupied Sov ...

. The participation of Ukrainian collaborators in these events, now documented and proven, is a matter of painful public debate in Ukraine".

Collaborating organizations, political movements, individuals and military volunteers

In total, the Germans enlisted 250,000 native Ukrainians for duty in five separate formations including the Nationalist Military Detachments (VVN), the Brotherhoods of Ukrainian Nationalists (DUN), the SS Division Galicia, theUkrainian Liberation Army

The Ukrainian Liberation Army (; ''Ukrainske Vyzvolne Viysko'', UVV) was an umbrella organization created in 1943, providing collective name for all Ukrainian units serving with the German Army during World War II. A single formation by that ...

(UVV) and the Ukrainian National Army

The Ukrainian National Army (, abbreviated , UNA) was a World War II Ukrainian military group, created on March 17, 1945, in the town of Weimar, Nazi Germany, and subordinate to Ukrainian National Committee.

History

The army, formed on April 1 ...

(''Ukrainische Nationalarmee'', UNA). Slavica Publishers. By the end of 1942, in Reichskommissariat Ukraine alone, the SS employed 238,000 native Ukrainian police and 15,000 Germans, a ratio of 1 to 16.

Auxiliary police

The 109th, 114th, 115th, 116th, 117th, 118th, 201st Ukrainian Schutzmannschaft-battalions participated inanti-partisan operations

During the Second World War, resistance movements that bore any resemblance to irregular warfare were frequently dealt with by the German occupying forces under the auspices of anti-partisan warfare. In many cases, the Nazis euphemistically used ...

in Ukraine and Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

. In February and March 1943, the 50th Ukrainian Schutzmannschaft Battalion participated in the large anti-guerrilla action « Operation Winterzauber» (Winter magic) in Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

, cooperating with several Latvian and the 2nd Lithuanian battalion. Schuma-battalions burned down villages suspected of supporting Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

partisans

Partisan(s) or The Partisan(s) may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

** Francs-tireurs et partisans, communist-led French anti-fascist resistance against Nazi Germany during WWII

** Itali ...

. On March 22, 1943, all inhabitants of the village of Khatyn in Belarus were burned alive by the Nazis in what became known as the Khatyn massacre

Khatyn (, ; , ) was a village of 26 houses and 157 inhabitants in Belarus, in Lahoysk Raion, Minsk Region, 50 km away from Minsk. On 22 March 1943, almost the entire population of the village was massacred by the Schutzmannschaft Battal ...

, with the participation of the 118th Schutzmannschaft battalion.

According to Paul R. Magocsi, "''Ukrainian auxiliary police and militia, or simply "Ukrainians" (a generic term that in fact included persons of non-Ukrainian as well as Ukrainian national background) participated in the overall process as policemen and camp guards''".

Ukrainian volunteers in the German armed forces

*Nachtigall Battalion

The Nachtigall Battalion (), also known as the Ukrainian Nightingale Battalion Group (), or officially as Special Group NachtigallAbbot, Peter. ''Ukrainian Armies 1914-55'', p.47. Osprey Publishing, 2004. ()

was a subunit under command of the Ge ...

* Roland Battalion

* Freiwilligen-Stamm-Division 3 and 4

SS Division Galicia

On 28 April 1943, the German Governor of the

On 28 April 1943, the German Governor of the District of Galicia

The District of Galicia (, , ) was a World War II administrative unit of the General Government created by Nazi Germany on 1 August 1941 after the start of Operation Barbarossa, based loosely within the borders of the ancient Principality o ...

, Otto Wächter

Baron Otto Gustav von Wächter (8 July 1901 – 14 July 1949) was an Austrian lawyer, Nazi politician and a high-ranking member of the SS, a paramilitary organisation of the Nazi Party. He participated in the Final Solution extermination of Jews ...

, and the local Ukrainian administration officially declared the creation of the SS Division Galicia. Volunteers signed for service as of 3 June 1943 and numbered 80,000. On 27 July 1944, the division was formed into the Waffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

as 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Ukrainian)

The 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician) (; ), commonly referred to as the Galicia Division, was a World War II infantry division (military), division of the Waffen-SS, the military wing of the German Nazi Party, made up predom ...

.GEORG TESSIN Verbande und Truppen der deutschen Wehrmacht und Waffen SS im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939-1945 DRITTER BAND: Die Landstreitkrafte 6—14 VERLAG E. S. MITTLER & SOHN GMBH. • FRANKFURT/MAIN page 313

Sol Litman of the Simon Wiesenthal Center

The Simon Wiesenthal Center (SWC) is a Jewish human rights organization established in 1977 by Rabbi Marvin Hier. The center is known for Holocaust research and remembrance, hunting Nazi war criminals, combating antisemitism, tolerance educati ...

states that there are many proven and documented incidents of atrocities and massacres committed by the unit against Poles and Jews during World War II. Official SS records show that the 4, 5, 6 and 7 SS-Freiwilligen regiments were under Ordnungspolizei

The ''Ordnungspolizei'' (''Orpo'', , meaning "Order Police") were the uniformed police force in Nazi Germany from 1936 to 1945. The Orpo was absorbed into the Nazi monopoly of power after regional police jurisdiction was removed in favour of t ...

command during the accusations. See 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of SS, the 1st Galician: Atrocities and war crimes.

Ukrainian National Committee

In March 1945, the Ukrainian National Committee was set up after a series of negotiations with the Germans. The Committee represented and had command over all Ukrainian units fighting for the Third Reich, such as theUkrainian National Army

The Ukrainian National Army (, abbreviated , UNA) was a World War II Ukrainian military group, created on March 17, 1945, in the town of Weimar, Nazi Germany, and subordinate to Ukrainian National Committee.

History

The army, formed on April 1 ...

. However, it was too late, and the committee and the army were disbanded at the end of the war.

Ukrainian Central Committee

Pavlo Shandruk

Pavlo Feofanovych Shandruk (; ; February 28, 1889 – February 15, 1979) was a general in the army of the Ukrainian National Republic, a colonel of the Polish Army, and a prominent general of the Ukrainian National Army, a military force t ...

became the head of the National Committee, while Volodymyr Kubijovyč

Volodymyr Kubijovyč (also spelled Kubiiovych or Kubiyovych; ; 23 September 1900 – 2 November 1985) was an anthropological geographer in prewar Poland, a wartime Ukrainian nationalist politician, a Nazi collaborator and a post-war émigré in ...

, the head of the , became his deputy. The Central Committee was the officially recognized Ukrainian community and quasi-political organization under the Nazi occupation of Poland

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was frequen ...

.

Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists

* Ukrainian National Government of the Ukrainian State, led by OUN-B. Suppressed by the Nazis shortly after its establishment.Heads of local Ukrainian administration and public figures under the German occupation

*Oleksander Ohloblyn

Oleksander Petrovych Ohloblyn (; 6 December 1899 – 16 February 1992) was a Ukrainian politician and historian who served as mayor of Kyiv while it was under the occupation of Nazi Germany in 1941. He was one of the most important Ukrainian � ...

(1899–1992) in the fall of 1941, Ohloblyn was appointed the Mayor of Kiev at the behest of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists

The Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN; ) was a Ukrainian nationalist organization established on February 2, 1929 in Vienna, uniting the Ukrainian Military Organization with smaller, mainly youth, radical nationalist right-wing groups. ...

. He held the post from September 21 to October 25.

* Volodymyr Bahaziy

Volodymyr Panteleimonovych Bahaziy (; 1902 – 21 February 1942) was a Ukrainian nationalist affiliated with Andriy Melnyk who was head of Kyiv City Administration under German occupation from October 1941 to February 1942.

Biography

Born i ...

(Kiev mayor, 1941–1942,

* Leontii Forostivsky (Kiev mayor, 1942–1943)

* Fedir Bohatyrchuk

Fedir Parfenovych Bohatyrchuk (also ''Bogatirchuk'', ''Bohatirchuk'', ''Bogatyrtschuk''; ; ; 27 November 1892 – 4 September 1984) was a Ukrainian–Canadian chess player, doctor of medicine (radiologist), political activist, and writer.

Russ ...

(head of the Ukrainian Red Cross, 1941–1942)

* Oleksii Kramarenko (Kharkov mayor, 1941–1942, executed by Germans in 1943)

* Oleksander Semenenko (Kharkov mayor, 1942–1943)

* Paul Kozakevich (Kharkov mayor, 1943)

* Aleksandr Sevastianov (Vinnytsia mayor, 1941 – ?)

See also

*Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy

In World War II, many governments, organizations and individuals Collaborationism, collaborated with the Axis powers, "out of conviction, desperation, or under coercion". Nationalists sometimes welcomed German or Italian troops they believed wou ...

* History of the Jews in Ukraine

The history of the Jews in Ukraine dates back over a thousand years; Jews, Jewish communities have existed in the modern territory of Ukraine from the time of the Kievan Rus' (late 9th to mid-13th century). Important Jewish religious and cultura ...

* List of Ukrainian Righteous Among the Nations

References

Further reading

* Armstrong, John Alexander (1968). Collaborationism in World War II: The Integral Nationalist Variant in Eastern Europe. ''The Journal of Modern History'', 40(3), pp. 396–410. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Ukrainian Collaboration With Nazi Germany Modern history of Ukraine Military history of Germany during World War II The Holocaust in Ukraine The Holocaust in Poland Ukrainian collaboration during World War II Nazi war crimes in the Soviet Union