Coalbrook Dale on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

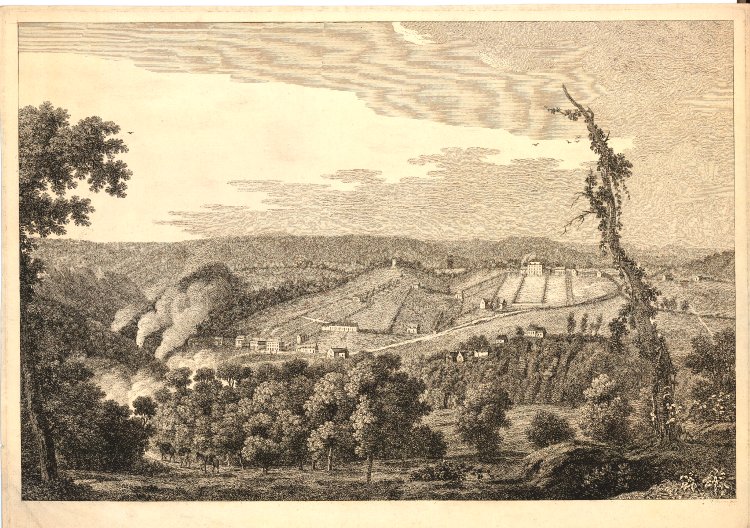

Coalbrookdale is a town in the

In 1709, the first Abraham Darby rebuilt Coalbrookdale Furnace, and eventually used coke as his fuel. His business was that of an ironfounder, making cast-iron pots and other goods, an activity in which he was particularly successful because of his patented foundry method, which enabled him to produce cheaper pots than his rivals. Coalbrookdale has been claimed as the home of the world's first coke-fired

In 1709, the first Abraham Darby rebuilt Coalbrookdale Furnace, and eventually used coke as his fuel. His business was that of an ironfounder, making cast-iron pots and other goods, an activity in which he was particularly successful because of his patented foundry method, which enabled him to produce cheaper pots than his rivals. Coalbrookdale has been claimed as the home of the world's first coke-fired  In 1802, the Coalbrookdale Company built a rail locomotive for

In 1802, the Coalbrookdale Company built a rail locomotive for

archaeology unit

continues to investigate the earlier history of Coalbrookdale, and has recently excavated the remains of the 17th century cementation furnaces, near the site of the Upper (formerly Middle)

*

*

''Religion, Gender, and Industry: Exploring Church and Methodism in a Local Setting''

, James Clarke & Co. (2012), . * Scarfe, Norman (1995) ''Innocent espionage: the La Rochefoucauld Brothers' tour of England in 1785'', Woodbridge : Boydell Press, * Trinder, Barrie Stuart (1988) ''The Most extraordinary district in the world: Ironbridge and Coalbrookdale: an anthology of visitors' impressions of Ironbridge, Coalbrookdale and the Shropshire coalfield'', 2nd ed., Chichester : Phillimore/Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust,

Coalbrookdale tourThe official Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust siteTelford Steam Railway

{{Authority control Telford and Wrekin Industrial Revolution Industrial history of the United Kingdom Ironworks and steelworks in England Ironbridge Gorge Towns in Shropshire The Gorge

Ironbridge Gorge

The Ironbridge Gorge is a deep gorge, containing the River Severn in Shropshire, England. It was first formed by a glacial overflow from the long drained away Lake Lapworth, at the end of the last ice age. The deep exposure of the rocks cut ...

and the Telford and Wrekin

Telford and Wrekin is a Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough and unitary authority in Shropshire, England. In 1974, a non-metropolitan district of Shropshire was created called the Wrekin, named after The Wrekin, a prominent hill to the ...

borough of Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government. Civil parishes can trace their origin to the ancient system of parishes, w ...

called the Gorge.

This is where iron ore was first smelted by Abraham Darby Abraham Darby may refer to:

People

*Abraham Darby I (1678–1717) the first of several men of that name in an English Quaker family that played an important role in the Industrial Revolution. He developed a new method of producing pig iron with ...

using easily mined "coking coal". The coal was drawn from drift mines in the sides of the valley. As it contained far fewer impurities than normal coal, the iron it produced was of a superior quality. Along with many other industrial developments that were going on in other parts of the country, this discovery was a major factor in the growing industrialisation of Britain, which was to become known as the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

. Today, Coalbrookdale is home to the Ironbridge Institute

The Ironbridge Institute is a centre offering postgraduate and professional development courses in cultural heritage, located in the Ironbridge Gorge region of Shropshire, England.

The institute is located in Coalbrookdale, just outside Ironbridg ...

, a partnership between the University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University) is a Public university, public research university in Birmingham, England. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingham (founded in 1825 as ...

and the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust

The Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust is an industrial heritage organisation which runs ten museums and manages multiple historic sites within the Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site in Shropshire, England, widely considered as the birthplace of t ...

offering postgraduate and professional development courses in heritage

Heritage may refer to:

History and society

* A heritage asset A heritage asset is an item which has value because of its contribution to a nation's society, knowledge and/or culture. Such items are usually physical assets, but some countries also ...

.

Before Abraham Darby

Before the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Madeley and the adjacentLittle Wenlock

Little Wenlock is a village and civil parish in the Telford and Wrekin borough in Shropshire, England. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 census was 605. It was mentioned in the Domesday Book, when it belonged to Wenlock Priory. An ...

belonged to Much Wenlock Priory

Wenlock Priory, or St Milburga's Priory, is a ruined 12th-century monastery, located in Much Wenlock, Shropshire, at . Roger de Montgomery re-founded the Priory as a Cluniac house between 1079 and 1082, on the site of an earlier 7th-century mo ...

. At the Dissolution there was a bloomsmithy called "Caldebroke Smithy". The manor passed about 1572 to John Brooke, who developed coal mining in his manor on a substantial scale. His son Sir Basil Brooke was a significant industrialist, and invested in ironworks elsewhere. It is probable that he also had ironworks at Coalbrookdale, but evidence is lacking. He also acquired an interest in the patent for the cementation process

The cementation process is an Obsolescence, obsolete technology for making steel by carburization of iron. Unlike modern steelmaking, it increased the amount of carbon in the iron. It was apparently developed before the 17th century. Derwentcot ...

of making steel in about 1615. Though forced to surrender the patent in 1619, he continued making iron and steel until his estate was sequestrated during the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, but the works continued in use.

In 1651, the manor was leased to Francis Wolfe, the clerk of the ironworks, and he and his son operated them as tenant of (or possibly manager for) Brooke's heirs. The surviving old blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

In a ...

contains a cast-iron lintel bearing a date, which is currently painted as 1638, but an archive photograph has been found showing it as 1658. What ironworks existed at Coalbrookdale and from precisely what dates thus remains obscure. By 1688, the ironworks were operated by Lawrence Wellington, but a few years after the furnace was occupied by Shadrach Fox. He renewed the lease in 1696, letting the Great Forge

A forge is a type of hearth used for heating metals, or the workplace (smithy) where such a hearth is located. The forge is used by the smith to heat a piece of metal to a temperature at which it becomes easier to shape by forging, or to the ...

and Plate Forge to Wellington. Some evidence may suggest that Shadrach Fox smelted iron with mineral coal, though this remains controversial. Fox was evidently an iron founder An iron founder (also iron-founder or ironfounder) in its more general sense is a worker in molten ferrous metal, generally working within an iron foundry. However, the term 'iron founder' is usually reserved for the owner or manager of an iron fou ...

, as he supplied round shot and grenade shells to the Board of Ordnance

The Board of Ordnance was a British government body. Established in the Tudor period, it had its headquarters in the Tower of London. Its primary responsibilities were 'to act as custodian of the lands, depots and forts required for the defence ...

during the Nine Years War

The Nine Years' War was a European great power conflict from 1688 to 1697 between France and the Grand Alliance. Although largely concentrated in Europe, fighting spread to colonial possessions in the Americas, India, and West Africa. Relat ...

, but not later than April 1703, the furnace blew up. It remained derelict until the arrival of Abraham Darby the Elder in 1709. However the forges remained in use. A brass works was built sometime before 1712 (possibly as early as 1706), but closed in 1714.

Industrial Revolution

In 1709, the first Abraham Darby rebuilt Coalbrookdale Furnace, and eventually used coke as his fuel. His business was that of an ironfounder, making cast-iron pots and other goods, an activity in which he was particularly successful because of his patented foundry method, which enabled him to produce cheaper pots than his rivals. Coalbrookdale has been claimed as the home of the world's first coke-fired

In 1709, the first Abraham Darby rebuilt Coalbrookdale Furnace, and eventually used coke as his fuel. His business was that of an ironfounder, making cast-iron pots and other goods, an activity in which he was particularly successful because of his patented foundry method, which enabled him to produce cheaper pots than his rivals. Coalbrookdale has been claimed as the home of the world's first coke-fired blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

In a ...

; this is not strictly correct, but it was the first in Europe to operate successfully for more than a few years.

Darby renewed his lease of the works in 1714, forming a new partnership with John Chamberlain and Thomas Baylies

Thomas Baylies (1687–March 1756) was a Quaker ironmaster first in England, then in Massachusetts.

Origins and family

Thomas Baylies was the son of Nicholas Baylies of Alvechurch in north Worcestershire. On 5 June 1706, he married Esther, d ...

. They built a second furnace in about 1715, which was intended to be followed up with a furnace in Wales at Dolgûn near Dolgellau

Dolgellau (; ) is a town and Community (Wales), community in Gwynedd, north-west Wales, lying on the River Wnion, a tributary of the River Mawddach. It was the traditional county town of the Historic counties of Wales, historic county of Merion ...

and in Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Merseyside to the north-west, Greater Manchester to the north-east, Derbyshire to the east, Staffordshire to the south-east, and Shrop ...

taking over Vale Royal Furnace in 1718. However, Darby died prematurely at Madeley Court

Madeley Court is a 16th-century country house in Madeley, Shropshire, England which was originally built as a Monastic grange, grange to the medieval Wenlock Priory. It has since been restored as a hotel.

The house is ashlar built in two storey ...

in 1717 – the same year as he began the house Dale End which became home to succeeding generations of the family in Coalbrookdale – followed quickly by his widow Mary. The partnership was dissolved before Mary's death, Baylies taking over Vale Royal. After Mary's death, Baylies had difficulty extracting his capital. The works then passed to a company led by his fellow Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

Thomas Goldney II of Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

and managed by Richard Ford

Richard Ford (born February 16, 1944) is an American novelist and short story author, and writer of a series of novels featuring the character Frank Bascombe.

Ford's first collection of short stories, ''Rock Springs (short stories), Rock Springs ...

(also a Quaker). Darby's son Abraham Darby the Younger was brought into the business as an assistant manager when old enough.

The company's main business was producing cast-iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

goods. Molten iron for this foundry work was not only produced from the blast furnaces, but also by remelting pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

in air furnaces, a variant of the reverberatory furnace

A reverberatory furnace is a metallurgy, metallurgical or process Metallurgical furnace, furnace that isolates the material being processed from contact with the fuel, but not from contact with combustion gases. The term ''reverberation'' is use ...

. The Company also became early suppliers of steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs Work (physics), mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a Cylinder (locomotive), cyl ...

cylinders in this period.

From 1720, the Company operated a forge at Coalbrookdale but this was not profitable. In about 1754, renewed experiments took place with the application of coke pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

to the production of bar iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

in charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ca ...

finery forge

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and decarburization, removing carbon from the molten cast iron through Redo ...

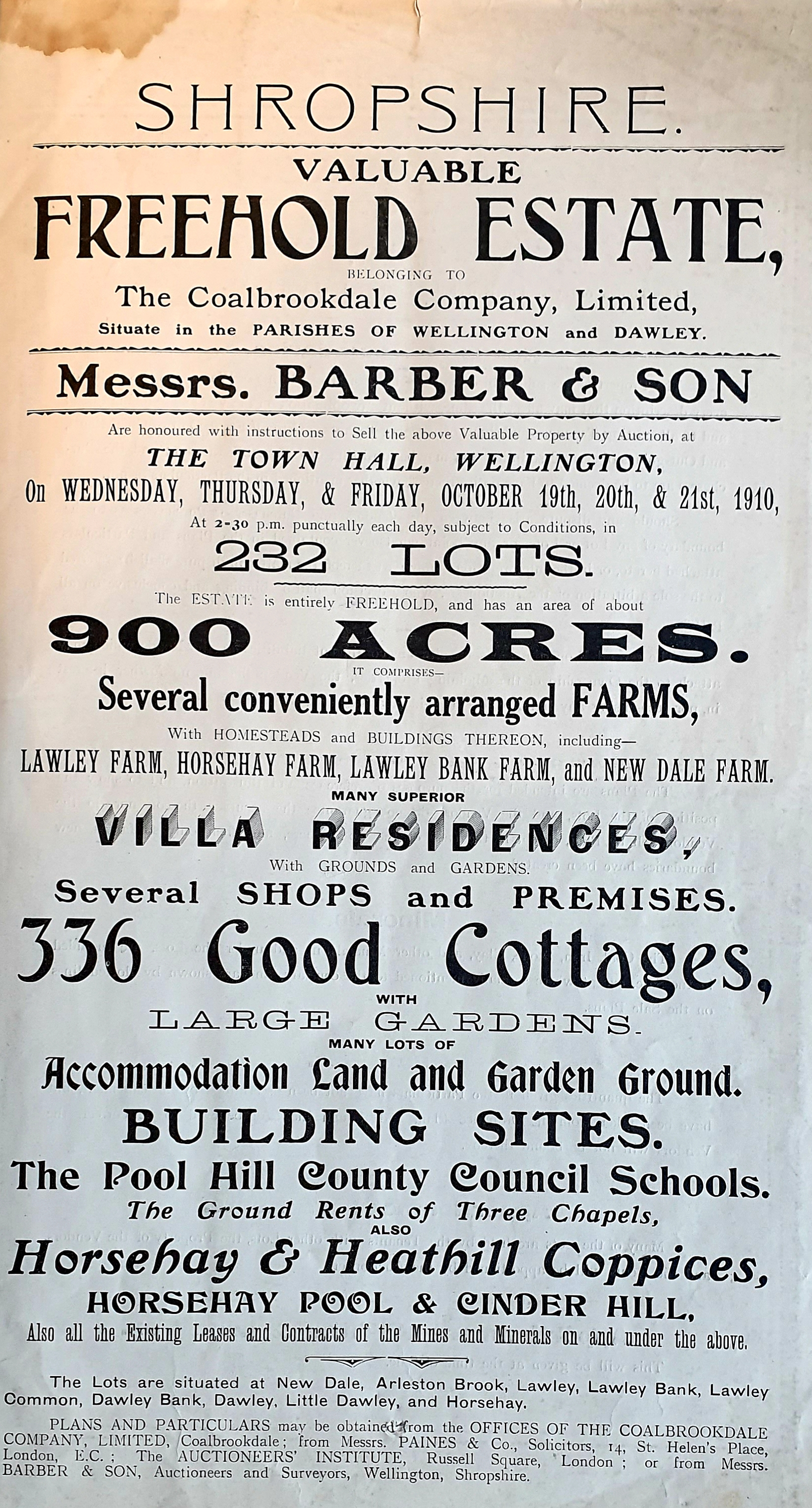

s. This proved to be a success, and led to the partners building new furnaces at Horsehay

Horsehay is a suburban village on the western outskirts of Dawley in the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England. Horsehay lies in the Dawley Hamlets parish, and on the northern edge of the Ironbridge Gorge area.

Horsehay used to hav ...

and Ketley

Ketley is a large village and civil parish in the borough of Telford and Wrekin of Shropshire, England. It is located between the outlying towns of Oakengates, Telford and Wellington.

Residential development

East Ketley is currently being r ...

. This was the beginning of a great expansion in coke ironmaking.

In 1767, the Company began to produce the first cast-iron rails

Rail or rails may refer to:

Rail transport

*Rail transport and related matters

* Railway track or railway lines, the running surface of a railway

Arts and media Film

* ''Rails'' (film), a 1929 Italian film by Mario Camerini

* ''Rail'' (1967 fi ...

for railway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in railway track, tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel railway track, rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of ...

s. In 1778, Abraham Darby III

Abraham Darby III (24 April 1750 – 1789) was an English ironmaster and Quaker. He was the third man of that name in several generations of an English Quaker family that played a pivotal role in the Industrial Revolution.

Life

Abraham Darby ...

undertook the building of the world's first cast-iron bridge, the iconic Iron Bridge, opened 1 January 1781. The fame of this bridge leads many people today to associate the iron-making part of the Industrial Revolution with the neighbouring village of Ironbridge

Ironbridge is a riverside village in the borough of Telford and Wrekin, Shropshire, England. Located on the bank of the River Severn, at the heart of the Ironbridge Gorge, it lies in the civil parish of The Gorge. Ironbridge developed beside, ...

, but in fact most of the work was done at Coalbrookdale, as there was no settlement at Ironbridge in the eighteenth century. Expansion of Coalbrookdale's industrial facilities continued, with the development of sophisticated ponds and culverts to provide water power, and even ''Resolution'', a water-returning beam engine to recirculate this water.

In 1795, the first porcelain factory near Coalbrookdale was founded at Coalport, east of the Iron Bridge, by William Reynolds and John Rose, producing Coalport

Coalport is a village in Shropshire, England. It is located on the River Severn in the Ironbridge Gorge, a mile downstream of Ironbridge. It lies predominantly on the north bank of the river; on the other side is Jackfield. It forms part of ...

porcelain.

In 1802, the Coalbrookdale Company built a rail locomotive for

In 1802, the Coalbrookdale Company built a rail locomotive for Richard Trevethick

Richard Trevithick (13 April 1771 – 22 April 1833) was a British inventor and mining engineer. The son of a mining captain, and born in the mining heartland of Cornwall, Trevithick was immersed in mining and engineering from an early age. He w ...

, but little is known about it, including whether or not it actually ran. The death of a company workman in an accident involving the engine is said to have caused the company to not proceed to running it on their existing railway.Article 'Shropshire Railways' by John Denton. To date, the only known information about it comes from a drawing preserved at the Science Museum, London

The Science Museum is a major museum on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, London. It was founded in 1857 and is one of the city's major tourist attractions, attracting 3.3 million visitors annually in 2019.

Like other publicly funded ...

, together with a letter written by Trevithick to his friend Davies Giddy

Davies Gilbert (born Davies Giddy, 6 March 1767 – 24 December 1839) was a British engineer, author, and politician. He was elected to the Royal Society on 17 November 1791 and served as its President from 1827 to 1830. He changed his name to ...

. The design incorporated a single horizontal cylinder

A cylinder () has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an infinite ...

enclosed in a return-flue boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, centra ...

. A flywheel

A flywheel is a mechanical device that uses the conservation of angular momentum to store rotational energy, a form of kinetic energy proportional to the product of its moment of inertia and the square of its rotational speed. In particular, a ...

drove the wheels on one side through spur gears

A gear or gearwheel is a rotating machine part typically used to transmit rotational motion and/or torque by means of a series of teeth that engage with compatible teeth of another gear or other part. The teeth can be integral saliences or c ...

, and the axles

An axle or axletree is a central shaft for a rotating wheel or gear. On wheeled vehicles, the axle may be fixed to the wheels, rotating with them, or fixed to the vehicle, with the wheels rotating around the axle. In the former case, bearin ...

were mounted directly on the boiler, with no frame. The drawing indicates that the locomotive ran on a plateway

A plateway is an early kind of railway, tramway or wagonway, where the rails are made from cast iron. They were mainly used for about 50 years up to 1830, though some continued later.

Plateways consisted of L-shaped rails, where the flange ...

with a track gauge

In rail transport, track gauge is the distance between the two rails of a railway track. All vehicles on a rail network must have Wheelset (rail transport), wheelsets that are compatible with the track gauge. Since many different track gauges ...

of . This was two years before Trevethick's first engine to tow a train was run at Penydarren in south Wales.

In the 19th century, Coalbrookdale was noted for its decorative ironwork. It is here (for example) that the gates of London's Hyde Park were built. Other examples include the Coalbrookdale verandah

A veranda (also spelled verandah in Australian and New Zealand English) is a roofed, open-air hallway or porch, attached to the outside of a building. A veranda is often partly enclosed by a railing and frequently extends across the front an ...

at St John's in Monmouth

Monmouth ( or ; ) is a market town and community (Wales), community in Monmouthshire, Wales, situated on where the River Monnow joins the River Wye, from the Wales–England border. The population in the 2011 census was 10,508, rising from 8 ...

, Wales, and as far away as the Peacock Fountain in Christchurch

Christchurch (; ) is the largest city in the South Island and the List of cities in New Zealand, second-largest city by urban area population in New Zealand. Christchurch has an urban population of , and a metropolitan population of over hal ...

, New Zealand. The blast furnaces were closed down, perhaps as early as the 1820s, but the foundries remained in use. The Coalbrookdale Company became part of an alliance of ironfounding companies called Light Castings Limited. This was absorbed by Allied Ironfounders Limited in 1929. This was in turn taken over by Glynwed which has since become Aga

Aga or AGA may refer to:

Business

* Architectural Glass and Aluminum (AGA), a glazing contractor, established in 1970

* AGA (automobile), , 1920s German car company

* AGA AB, , a Swedish company, the originator of the AGA cooker

* AGA Rangemaster ...

Foodservice. The Coalbrookdale foundry closed in November 2017.

Several of Coalbrookdale's industrial heritage sites are to be found on the local trail: including: Coalbrookdale railway station

Coalbrookdale railway station is a disused station that served both Coalbrookdale and Ironbridge in Shropshire, England. The station was situated on the now mothballed freight-only line between Buildwas Junction and Lightmoor Junction. The sta ...

, the Quaker Burial Ground, the Darby Houses, Tea Kettle Row and the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a History of rail transport in Great Britain, British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, ...

Viaduct.

Museum

In the century after the Old Blast Furnace closed, it became buried. There was a proposal for the site to be cleared and the furnace dismantled, but instead, it was decided to excavate and preserve it. It and a small museum were opened to celebrate 250 years of the Company in 1959. This became part of a larger project, theIronbridge Gorge Museums

The Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust is an industrial heritage organisation which runs ten museums and manages multiple historic sites within the Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site in Shropshire, England, widely considered as the birthplace of t ...

. Its Museum of Iron is based in the Great Warehouse constructed in 1838 and Ironbridge Institute is based in the Long Warehouse, these two form the sides of an open space. On another side of which is the Old Blast Furnace, now under a building (erected in 1981) to protect it from the weather. The fourth side is a viaduct carrying the railway that delivered coal to the now demolished Ironbridge Power Station

The Ironbridge power stations (also known as the Buildwas power stations) refers to two power stations that occupied a site on the banks of the River Severn at Buildwas in Shropshire, England. The Ironbridge B Power Station was operated by E.ON ...

. One of the two tracks is due to be taken over by Telford Steam Railway

The Telford Steam Railway (TSR) is a heritage railway located at Horsehay, Telford in Shropshire, England, formed in 1976.

The railway is operated by volunteers on Sundays and Bank holiday, Bank Holidays from Easter to the end of September, an ...

as part of its southern extension from Horsehay. The Museum'archaeology unit

continues to investigate the earlier history of Coalbrookdale, and has recently excavated the remains of the 17th century cementation furnaces, near the site of the Upper (formerly Middle)

Forge

A forge is a type of hearth used for heating metals, or the workplace (smithy) where such a hearth is located. The forge is used by the smith to heat a piece of metal to a temperature at which it becomes easier to shape by forging, or to the ...

.

Old Furnace

The Old Furnace began life as a typical blast furnace, but went over to coke in 1709.Abraham Darby I

Abraham Darby, in his later life called Abraham Darby the Elder, now sometimes known for convenience as Abraham Darby I (14 April 1677 – 5 May 1717, the first and best known of Abraham Darby (disambiguation), several men of that name), was ...

used it to cast pots, kettles and other goods. His grandson Abraham Darby III

Abraham Darby III (24 April 1750 – 1789) was an English ironmaster and Quaker. He was the third man of that name in several generations of an English Quaker family that played a pivotal role in the Industrial Revolution.

Life

Abraham Darby ...

smelted

Smelting is a process of applying heat and a chemical reducing agent to an ore to extract a desired base metal product. It is a form of extractive metallurgy that is used to obtain many metals such as iron, copper, silver, tin, lead and zinc. Sm ...

the iron here for the first Ironbridge

Ironbridge is a riverside village in the borough of Telford and Wrekin, Shropshire, England. Located on the bank of the River Severn, at the heart of the Ironbridge Gorge, it lies in the civil parish of The Gorge. Ironbridge developed beside, ...

, the world's first iron bridge.

The lintels of the furnace bear dated inscriptions. The uppermost reads "Abraham Darby 1777", probably recording its enlargement for casting the Iron Bridge. It is unclear whether the date on one of the lower ones should be 1638 (as it is now painted) or 1658 (as shown on an old photo). The interior profile of the furnace is typical of its period, bulging around the middle, below which the boshes taper in again so that the charge descends into a narrower and hotter hearth, where the iron was molten. When Abraham Darby III enlarged the furnace, he only made the boshes wider on the front and left sides, but not on the right where doing so would have entailed moving the water wheel. The mouth of the furnace is thus off-centre.

Iron was now being made in large quantities for many customers. In the 1720s and 1730s, its main products were cast-iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

cooking pots, kettle

A kettle, sometimes called a tea kettle or teakettle, is a device specialized for boiling water, commonly with a ''lid'', ''spout'', and ''handle''. There are two main types: the ''stovetop kettle'', which uses heat from a cooktop, hob, and the ...

s and other domestic articles. It also cast the cylinders for steam engines

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs Work (physics), mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a Cylinder (locomotive), cyl ...

, and pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

for use by other foundries

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

. In the late 18th century, it sometimes produced structural ironwork, including for Buildwas

Buildwas is a village and civil parish in Shropshire, England, on the north bank of the River Severn at . It lies on the B4380 road between Atcham and Ironbridge. The Royal Mail postcodes begin TF6 and TF8.

Buildwas Primary Academy is sit ...

Bridge. This was built in 1795, 2 miles up the river from the original Ironbridge. Due to advances in technology, it used only half as much cast iron despite being 30 feet (9 m) wider than the Ironbridge. The year after that, in 1796, Thomas Telford

Thomas Telford (9 August 1757 – 2 September 1834) was a Scottish civil engineer. After establishing himself as an engineer of road and canal projects in Shropshire, he designed numerous infrastructure projects in his native Scotland, as well ...

began a new project, Longdon-on-Tern Aqueduct

The Longdon-upon-Tern Aqueduct, near Longdon-upon-Tern in Shropshire, was one of the first two canal aqueducts to be built from cast iron.

History

The cast iron canal aqueduct was re-engineered by Thomas Telford after the first construction ...

. It carried the Shrewsbury Canal

The Shrewsbury Canal (or Shrewsbury and Newport Canal) was a canal in Shropshire, England. Authorised in 1793, the main line from Trench to Shrewsbury was fully open by 1797, but it remained isolated from the rest of the canal network until 183 ...

over the River Tern

The River Tern (also historically known as the Tearne) is a river in Shropshire, England. It rises north-east of Market Drayton in the north of the county. The source of the Tern is considered to be the lake in the grounds of Maer Hall, Staff ...

and was supported by cast-iron columns. Charles Bage

Charles Woolley Bage (1751–1822) was an English architect, born in a Quaker family

"Bage Way", part of Shrewsbury's 20th century inner ring road which links Old Potts Way to Crowmere Road, was named for him.

References

1751 births

18 ...

designed and built the world's first multi-storey cast-iron-framed mill. It used only brick and iron, with no wood, to improve its fire-resistance. In the 19th century ornamental ironwork became a speciality.

Notable residents

Abraham Darby II

Abraham Darby, in his lifetime called Abraham Darby the Younger, referred to for convenience as Abraham Darby II (12 May 1711 – 31 March 1763) was the second man of that name in an English Quaker family that played an important role in the ea ...

(1711–1763), ironmaster,

*Abiah Darby

Abiah Darby (born Abiah Maude; 1716–1794) was an English minister in the Quaker church based in Coalbrookdale, Shropshire. She was also the wife of the iron industrialist Abraham Darby. Abiah kept a journal and she sent letters which recorded ...

(1716–1794), minister in the Quaker church, wife of the above.

*Abraham Darby III

Abraham Darby III (24 April 1750 – 1789) was an English ironmaster and Quaker. He was the third man of that name in several generations of an English Quaker family that played a pivotal role in the Industrial Revolution.

Life

Abraham Darby ...

(1750–1794), ironmaster.

*Abraham Darby IV

Abraham Darby IV (30 March 1804 – 28 November 1878) was an English ironmaster.

He was born in Dale House, Coalbrookdale, Shropshire the son of Edmund Darby, a member of the Darby ironmaking family, and Lucy (née Burlingham) Darby. He was a G ...

(1804-1878), ironmaster.and

* William Reynolds (1758–1803), an ironmaster and a partner in the local ironworks * Thomas Parker FRSE (1843–1915), an electrical engineer, inventor and industrialist. *Arthur Charles Fox-Davies

Arthur Charles Fox-Davies (28 February 1871 – 19 May 1928) was a British expert on heraldry. His ''Complete Guide to Heraldry'', published in 1909, has become a standard work on heraldry in England. A barrister by profession, Fox-Davies worke ...

(1871–1928), writer and heraldic expert, brought up locally

* Rowsby Woof (1883–1943), violinist and music educator.

See also

*Ironbridge Gorge Museums

The Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust is an industrial heritage organisation which runs ten museums and manages multiple historic sites within the Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site in Shropshire, England, widely considered as the birthplace of t ...

* Green Wood Centre

The Green Wood Centre in Coalbrookdale, Shropshire – formerly the Green Wood Trust, which was formed in 1984 with the help of many volunteers and specialists who were concerned about the environment – is now the home of thSmall Woods Associa ...

* ''Resolution''

* Listed buildings in The Gorge

The Gorge, Shropshire, The Gorge is a civil parish in the district of Telford and Wrekin, Shropshire, England. It contains 215 Listed building#England and Wales, listed buildings that are recorded in the National Heritage List for England. Of t ...

* Holy Trinity Church, Coalbrookdale

Holy Trinity Church is an Anglicanism, Anglican church in Coalbrookdale, Shropshire, England. It is part of the United Benefice of Coalbrookdale, Ironbridge and Little Wenlock, in the Diocese of Hereford. The building is listed building, Grade II* ...

Notes

References

* Baugh, G.C. (Ed.) (1985) ''A History of Shropshire, Vol. XI: Telford, the Liberty & Borough of Wenlock (part), Bradford hundred'', Victoria history of the counties of England, Oxford University Press ; London : Institute of Historical Research, * Cox, N. (1990) "Imagination and Innovation of an Industrial Pioneer: the First Abraham Darby", ''Industrial Archaeology Review'', XII (1), pp. 127–144. * King, P. W. (2002) "Sir Clement Clerke and the Adoption of Coal in Metallurgy", ''Trans. Newcomen Soc.'', 73A, pp. 33–52. * King, P. W. "Technological Advance in the Severn Gorge", in P. Belford ''et al.'', ''Footprints of Industry: papers from the 300th anniversary conference at Coalbrookdale, 3–7 June 2009'' (BAR British Series 523, 2010). *Labouchere, Rachel – Deborah Darby of Coalbrookdale – Sessions: York, 1993. *Labouchere, Rachel – Abiah Darby of Coalbrookdale, 1716–93, Wife of Agraham Darby II – Sessions : York, 1988. * Raistrick, Arthur (1989) ''Dynasty of iron founders: the Darbys and Coalbrookdale'', 2nd rev. ed., Coalbrookdale : Sessions Book Trust/Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, * Thomas, E. (1999) ''Coalbrookdale and the Darby family: the story of the world's first industrial dynasty'', York : Sessions/Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, * Trinder, B. (1978) ''The Darbys of Coalbrookdale'', Rev. imp., London : Phillimore/Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, * Trinder, B. (1996) ''The Industrial Archaeology of Shropshire'', Chichester : Phillimore, * Trinder, B. (2000) ''The Industrial Revolution in Shropshire'', 3rd rev. ed., Chichester : Phillimore, * Geordan Hammond and Peter S. Forsaith (eds), ''Religion, Gender, and Industry: Exploring Church and Methodism in a Local Setting'' (Eugene, OR, Pickwick Publications, 2011).Further reading

* * Berg, Torsten and Berg, Peter (transl.) (2001) ''R.R. Angerstein's illustrated travel diary, 1753–1755: industry in England and Wales from a Swedish perspective'', London : Science Museum, * Hammond, Geordan and Forsaith, Peter S. (eds)''Religion, Gender, and Industry: Exploring Church and Methodism in a Local Setting''

, James Clarke & Co. (2012), . * Scarfe, Norman (1995) ''Innocent espionage: the La Rochefoucauld Brothers' tour of England in 1785'', Woodbridge : Boydell Press, * Trinder, Barrie Stuart (1988) ''The Most extraordinary district in the world: Ironbridge and Coalbrookdale: an anthology of visitors' impressions of Ironbridge, Coalbrookdale and the Shropshire coalfield'', 2nd ed., Chichester : Phillimore/Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust,

External links

Coalbrookdale tour

{{Authority control Telford and Wrekin Industrial Revolution Industrial history of the United Kingdom Ironworks and steelworks in England Ironbridge Gorge Towns in Shropshire The Gorge