Coal And Iron Police on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Coal and Iron Police (C&I) was a

Prior to 1865 (and until 1905), Law enforcement in Pennsylvania existed only on the county level or below; an elected sheriff was the primary law enforcement officer (for each county). With the construction of the railroad, the Pennsylvania hinterlands were opened up to development. As mining and coal-powered industries like iron and steel manufacturing expanded, Coal, railroad and iron operators made the case that they required additional protection of their property. Thus the Pennsylvania State Legislature passed State Act 228. This empowered the railroads to organize private police forces. In 1866, a supplement to the act was passed extending the privilege to "embrace all corporations, firms, or individuals, owning, leasing, or being in possession of any colliery, furnace, or rolling mill within this commonwealth". The 1866 supplement also stipulated that the words "coal and iron police" appear on their badges. For one dollar each, the state sold to the mine and steel mill owners commissions conferring police power upon whoever the owners selected. A total of 7,632 commissions were given for the Coal and Iron Police. In 1871, Governor John White Geary instituted a $1 fee for each C&I commission. Prior to that, there was no cost associated with obtaining the legal right to hire a private policeman.

Although the Coal and Iron Police nominally existed solely to protect company property, in practice the companies used them as strikebreakers, and to coerce and discipline workers and their families. C&Is were sometimes used to crack down on unemployed miners and the families of miners' practice of "bootlegging" or picking up loose scraps of coal along the railways to sell or for use heating their homes. Many coal miners disdained the C&Is and called them "

Prior to 1865 (and until 1905), Law enforcement in Pennsylvania existed only on the county level or below; an elected sheriff was the primary law enforcement officer (for each county). With the construction of the railroad, the Pennsylvania hinterlands were opened up to development. As mining and coal-powered industries like iron and steel manufacturing expanded, Coal, railroad and iron operators made the case that they required additional protection of their property. Thus the Pennsylvania State Legislature passed State Act 228. This empowered the railroads to organize private police forces. In 1866, a supplement to the act was passed extending the privilege to "embrace all corporations, firms, or individuals, owning, leasing, or being in possession of any colliery, furnace, or rolling mill within this commonwealth". The 1866 supplement also stipulated that the words "coal and iron police" appear on their badges. For one dollar each, the state sold to the mine and steel mill owners commissions conferring police power upon whoever the owners selected. A total of 7,632 commissions were given for the Coal and Iron Police. In 1871, Governor John White Geary instituted a $1 fee for each C&I commission. Prior to that, there was no cost associated with obtaining the legal right to hire a private policeman.

Although the Coal and Iron Police nominally existed solely to protect company property, in practice the companies used them as strikebreakers, and to coerce and discipline workers and their families. C&Is were sometimes used to crack down on unemployed miners and the families of miners' practice of "bootlegging" or picking up loose scraps of coal along the railways to sell or for use heating their homes. Many coal miners disdained the C&Is and called them "

A July 25, 1922, article in the ''Johnstown Tribune'' noted that additional Coal and Iron Police were hired during the national coal miner's strike in 1922.

In February 1927 Coal and Iron Police officers Paul Fox and Lewis Knapp were killed in the line of duty after coming upon two suspects with illegal

A July 25, 1922, article in the ''Johnstown Tribune'' noted that additional Coal and Iron Police were hired during the national coal miner's strike in 1922.

In February 1927 Coal and Iron Police officers Paul Fox and Lewis Knapp were killed in the line of duty after coming upon two suspects with illegal ODMP Paul R Fox

/ref> In 1929, Michael Musmanno, a Pennsylvania state legislator, fought to banish the Coal and Iron Police after they had beaten worker John Barcoski to death. The final disbandment was helped along by Musmanno's writing a short story based on the case, which was adapted into the 1935 film '' Black Fury''. Decades later Musmanno released a

''

private police

Private police or special police are types of Law enforcement agency, law enforcement agencies owned and/or controlled by non-government entities. Additionally, the term can refer to an off-duty police officer while working for a private entity ...

force in the US state of Pennsylvania that existed between 1865 and 1931. It was established by the Pennsylvania General Assembly

The Pennsylvania General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The legislature convenes in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg. In colonial times (1682–1776), the legislature was known as the Pennsylvani ...

but employed and paid for by the various coal companies. The Coal and Iron Police worked alongside the Pennsylvania National Guard, and later the Pennsylvania State Police, beginning in 1877. The remaining Coal and Iron Police commissions were allowed to expire in 1931, ostensibly ending the state-sanctioned organization of a private police force. Industrial policing continued in limited form until the later 1930s, when the National Labor Relations Act

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, is a foundational statute of United States labor law that guarantees the right of private sector employees to organize into trade unions, engage in collective bargaining, an ...

, the Fair Labor Standards Act

The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA) is a United States labor law that creates the right to a minimum wage, and " time-and-a-half" overtime pay when people work over forty hours a week. It also prohibits employment of minors in "oppre ...

, and other federal legislation made armed industrial forces illegal.

Establishment

Prior to 1865 (and until 1905), Law enforcement in Pennsylvania existed only on the county level or below; an elected sheriff was the primary law enforcement officer (for each county). With the construction of the railroad, the Pennsylvania hinterlands were opened up to development. As mining and coal-powered industries like iron and steel manufacturing expanded, Coal, railroad and iron operators made the case that they required additional protection of their property. Thus the Pennsylvania State Legislature passed State Act 228. This empowered the railroads to organize private police forces. In 1866, a supplement to the act was passed extending the privilege to "embrace all corporations, firms, or individuals, owning, leasing, or being in possession of any colliery, furnace, or rolling mill within this commonwealth". The 1866 supplement also stipulated that the words "coal and iron police" appear on their badges. For one dollar each, the state sold to the mine and steel mill owners commissions conferring police power upon whoever the owners selected. A total of 7,632 commissions were given for the Coal and Iron Police. In 1871, Governor John White Geary instituted a $1 fee for each C&I commission. Prior to that, there was no cost associated with obtaining the legal right to hire a private policeman.

Although the Coal and Iron Police nominally existed solely to protect company property, in practice the companies used them as strikebreakers, and to coerce and discipline workers and their families. C&Is were sometimes used to crack down on unemployed miners and the families of miners' practice of "bootlegging" or picking up loose scraps of coal along the railways to sell or for use heating their homes. Many coal miners disdained the C&Is and called them "

Prior to 1865 (and until 1905), Law enforcement in Pennsylvania existed only on the county level or below; an elected sheriff was the primary law enforcement officer (for each county). With the construction of the railroad, the Pennsylvania hinterlands were opened up to development. As mining and coal-powered industries like iron and steel manufacturing expanded, Coal, railroad and iron operators made the case that they required additional protection of their property. Thus the Pennsylvania State Legislature passed State Act 228. This empowered the railroads to organize private police forces. In 1866, a supplement to the act was passed extending the privilege to "embrace all corporations, firms, or individuals, owning, leasing, or being in possession of any colliery, furnace, or rolling mill within this commonwealth". The 1866 supplement also stipulated that the words "coal and iron police" appear on their badges. For one dollar each, the state sold to the mine and steel mill owners commissions conferring police power upon whoever the owners selected. A total of 7,632 commissions were given for the Coal and Iron Police. In 1871, Governor John White Geary instituted a $1 fee for each C&I commission. Prior to that, there was no cost associated with obtaining the legal right to hire a private policeman.

Although the Coal and Iron Police nominally existed solely to protect company property, in practice the companies used them as strikebreakers, and to coerce and discipline workers and their families. C&Is were sometimes used to crack down on unemployed miners and the families of miners' practice of "bootlegging" or picking up loose scraps of coal along the railways to sell or for use heating their homes. Many coal miners disdained the C&Is and called them "Cossack

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borders of Ukraine and Rus ...

s" and "Yellow Dogs". Common gunmen, hoodlums, and adventurers were often hired to fill these commissions. They served their own interests and regularly abused their power.

The first Coal and Iron Police were established in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania

Schuylkill County (, ; Pennsylvania Dutch language, Pennsylvania Dutch: Schulkill Kaundi) is a County (United States), county in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the ...

, under the supervision of the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Beginning in 1873, the Coal and Iron Police worked with the Pinkertons, particularly with a labor spy

Labor spying in the United States had involved people recruited or employed for the purpose of Intelligence gathering network, gathering intelligence, committing sabotage, sowing dissent, or engaging in other similar activities, in the context of ...

by the name of James McParland, to infiltrate and suppress the Molly Maguires

The Molly Maguires was an Irish people, Irish 19th-century secret society active in Ireland, Liverpool, and parts of the eastern United States, best known for their activism among Irish-American and Irish diaspora, Irish immigrant coal miners i ...

. During McParland's undercover investigation, Allan Pinkerton pursued a dual-track strategy, appointing R.J. Linden as head of the local Coal and Iron Police. McParland's undercover work led to the arrest and execution of 20 suspected Molly Maguires, but not without complications. Violence continued throughout the investigation. Tamaqua police officer Benjamin Yost was murdered in 1875 and the Mollies were blamed. This incident turned some of the public against the Mollies. Later that year, an Irish family was murdered by gunmen under suspicious circumstances. The attack was thought to have been motivated by revenge for the alleged murder of mine boss Thomas Sanger by Charles Kehoe, a leader of the Mollies. Though the gunmen were never brought to trial, later evidence implicated Pinkerton, McParland, and Linden. Many in the Irish-American

Irish Americans () are Irish ethnics who live within in the United States, whether immigrants from Ireland or Americans with full or partial Irish ancestry.

Irish immigration to the United States

From the 17th century to the mid-19th c ...

working class at the time, and some scholars today, question whether tales of the Molly Maguires were invented by the Pinkertons to justify repression in the anthracite coal fields. Many suspected Mollies maintained their innocence throughout the proceedings against them.

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. The Great Railroad Strike of 187 ...

led to increased public-private police cooperation, with Pennsylvania National Guard regiments and eventually federal troops deployed when Pinkertons and Coal and Iron Police failed to quell disorder on their own. The difficulties faced by Pennsylvania authorities in routing entrenched strikers led to reforms in the state's National Guard, and established a stronger role for the state in preserving order in industrial disputes.

On 16 March 1892 Coal and Iron police officer John Merget was shot and killed when he tried to stop 3 tramps from stealing from a boxcar; two suspects were convicted of second degree murder.

Coal and Iron Police again played a significant role in the 1892 Homestead Strike. As in 1877, The C&Is were overwhelmed by striking workers. They were herded together with the sheriff and local militia and sent away from town on a boat. The state's National Guard was again summoned to put down the strike.

In 1897, at least nineteen striking mineworkers were killed and dozens more were injured while marching to Lattimer, after a posse of deputies and company police fired on the unarmed crowd. The Lattimer Massacre bolstered sympathy and support for the miners' grievances and marked a turning point in the history of the United Mine Workers of America

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the Unit ...

. None of the deputies or company police were convicted for the murder of the unarmed workers.

Transition to state policing

The end of the Coal and Iron Police began in 1902 during what became known as the Anthracite coal strike. It began May 15 and lasted until October 23. The strike led to violence throughout seven counties and caused a nationwide coal shortage, driving up the price ofanthracite

Anthracite, also known as hard coal and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a lustre (mineralogy)#Submetallic lustre, submetallic lustre. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy densit ...

coal. The strike did not end until President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

intervened. In the aftermath of the strike, there was growing determination that peace and order should be maintained by regularly appointed and responsible officers employed by the public. In March of 1903, Roosevelt's coal commission recommended the abolition of the Coal and Iron Police.

Though the Roosevelt commission's recommendation was not heeded, it added to the public pressure which led to the formation of the Pennsylvania State Police

The Pennsylvania State Police (PSP) is the state police, state police agency of the U.S. state of Pennsylvania, responsible for statewide law enforcement. The Pennsylvania State Police is a full service law enforcement agency which handles both ...

on May 2, 1905, when Senate Bill 278 was signed into law by Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

Samuel W. Pennypacker. The stated purpose was to act as fire, forest, game and fish wardens, and to protect the farmers, but some observers felt that it really was to serve the interests of the coal and iron operators because the same legislation created a "trespassing offense" that wherever a warning sign was displayed a person could be arrested and fined ten dollars. This was seen as a direct assault on picketing

Picketing is a form of protest in which people (called pickets or picketers) congregate outside a place of work or location where an event is taking place. Often, this is done in an attempt to dissuade others from going in (" crossing the pi ...

.

The Coal and Iron Police continued to exist even after the establishment of the state police. The state police often collaborated with Coal and Iron Police to the benefit of industrial interests and the detriment of labor. During the Westmoreland County coal strike of 1910–1911, the Pennsylvania State Police worked with the Coal and Iron Police to suppress the strike. Coal and Iron Police served as enforcers on company property during the workday, and state police harassed and surveilled the workers outside of company property and time. The two police forces worked together to evict a mostly Slovakian workforce from company-owned homes, forcing the workers to spend the winter in tents provided by the UMWA. When the company imported strikebreaker

A strikebreaker (sometimes pejoratively called a scab, blackleg, bootlicker, blackguard or knobstick) is a person who works despite an ongoing strike. Strikebreakers may be current employees ( union members or not), or new hires to keep the orga ...

s to the region, many of whom had little to no English-speaking ability, the C&I corralled the workers in company housing complexes and forced them to work, even as some attempted to leave. Sixteen strikers and their wives were killed during the strike.

In August 1911 a Coal and Iron Policeman, Deputy Constable Edgar Rice of Coatesville, Pennsylvania

Coatesville is the only city in Chester County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 13,350 at the 2020 census. Coatesville is approximately 39 miles west of Philadelphia. It developed along the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike ...

, was shot and killed by Zachariah Walker; Walker was lynched by a mob a few days later.

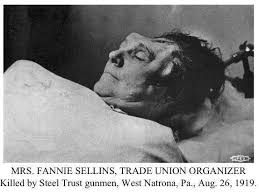

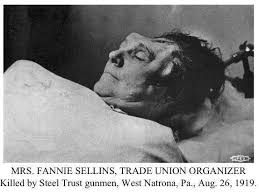

In 1919, labor organizer Fannie Sellins was beaten and shot by Coal and Iron Police when she intervened to stop the beating of Joseph Starzleski, a mineworker. Both Sellins and Starzleski were killed.

A July 25, 1922, article in the ''Johnstown Tribune'' noted that additional Coal and Iron Police were hired during the national coal miner's strike in 1922.

In February 1927 Coal and Iron Police officers Paul Fox and Lewis Knapp were killed in the line of duty after coming upon two suspects with illegal

A July 25, 1922, article in the ''Johnstown Tribune'' noted that additional Coal and Iron Police were hired during the national coal miner's strike in 1922.

In February 1927 Coal and Iron Police officers Paul Fox and Lewis Knapp were killed in the line of duty after coming upon two suspects with illegal moonshine

Moonshine is alcohol proof, high-proof liquor, traditionally made or distributed alcohol law, illegally. The name was derived from a tradition of distilling the alcohol (drug), alcohol at night to avoid detection. In the first decades of the ...

. One suspect was executed in 1929, and the other served 15 years in prison./ref> In 1929, Michael Musmanno, a Pennsylvania state legislator, fought to banish the Coal and Iron Police after they had beaten worker John Barcoski to death. The final disbandment was helped along by Musmanno's writing a short story based on the case, which was adapted into the 1935 film '' Black Fury''. Decades later Musmanno released a

novel

A novel is an extended work of narrative fiction usually written in prose and published as a book. The word derives from the for 'new', 'news', or 'short story (of something new)', itself from the , a singular noun use of the neuter plural of ...

of the same name.

In 1931, Governor Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsyl ...

refused to renew or issue new private police commissions, thereby effectively ending the industrial police system in Pennsylvania."Industrial Police"''

Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' February 9, 1931. The reasons for his act are not clear and may have included political payback for his defeat in a 1926 campaign by a candidate from Indiana County who had the strong support of the coal and steel operators, as a political gesture to the rising labor movement of the 1930s, out of personal disgust with the excesses of the Coal and Iron Police, or some combination thereof. His official statement indicates the latter, in reference to an assault perpetrated by a couple of Iron Policemen.

The brutality of the Coal and Iron Police forms the background to some sections in Dos Passos's ''U.S.A.'' trilogy, focusing on miners' struggles and strikes in Pennsylvania. The Coal and Iron Police also feature in the Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a Detective fiction, fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a "Private investigator, consulting detective" in his stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with obser ...

novel, '' The Valley of Fear'', which is based loosely on the breaking of the Molly Maguires

The Molly Maguires was an Irish people, Irish 19th-century secret society active in Ireland, Liverpool, and parts of the eastern United States, best known for their activism among Irish-American and Irish diaspora, Irish immigrant coal miners i ...

.

See also

* State Police of Crawford and Erie Counties *Auxiliary police

Auxiliary police, also called volunteer police, reserve police, assistant police, civil guards, or special police, are usually the part-time reserves of a regular police force. They may be unpaid volunteers or paid members of the police servic ...

* Railroad police

Railroad police or railway police are people responsible for the protection of Rail transport, railroad (or railway) properties, facilities, revenue, equipment (train cars and locomotives), and personnel, as well as carried passengers and cargo. R ...

* Security police

Security police usually describes a law enforcement agency which focuses primarily on providing security and law enforcement services to particular areas or specific properties. They may be employed by governmental, public, or private institutio ...

* Special police

* Company police

Company police are a form of private police and are law enforcement officers (LEOs) that work for companies rather than governmental entities; they may be employed directly by a private corporation or by a private security company which contracts ...

* Murder of workers in labor disputes in the United States

References

Further reading

* Meyerhuber, Jr., Carl I. ''Less than Forever: The Rise and Decline of Union Solidarity in Western Pennsylvania, 1914-1948''. Selingsgrove, Pa.: Susquehanna University Press, 1987. * Norwood, Stephen H. ''Strikebreaking and Intimidation: Mercenaries and Masculinity in Twentieth-Century America''. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. {{ISBN, 978-0-8078-2705-5 Government agencies established in 1865 1931 disestablishments in Pennsylvania History of labor relations in the United States Coal in the United States Defunct law enforcement agencies of Pennsylvania 1865 establishments in Pennsylvania Private police in the United States