Clyde Arwood on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Clyde Arwood (September 7, 1901 – August 14, 1943) was the only person executed by the

Following Arwood's parole, Arwood moved back to Lauderdale County and began operating an illegal

Following Arwood's parole, Arwood moved back to Lauderdale County and began operating an illegal

United States federal government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct ...

in Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

. He was sentenced to death after his conviction of murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse committed with the necessary Intention (criminal law), intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisd ...

ing William Pugh, a federal agent, during a raid of Arwood's illegal still

A still is an apparatus used to distillation, distill liquid mixtures by heating to selectively Boiling, boil and then cooling to Condensation, condense the vapor. A still uses the same concepts as a basic Distillation#Laboratory_procedures, ...

.

Arwood was executed in the electric chair

The electric chair is a specialized device used for capital punishment through electrocution. The condemned is strapped to a custom wooden chair and electrocuted via electrodes attached to the head and leg. Alfred P. Southwick, a Buffalo, New Yo ...

at age 41 in Tennessee State Penitentiary

Tennessee State Prison is a former correctional facility located six miles west of downtown Nashville, Tennessee on Cockrill Bend. It opened in 1898 and has been closed since 1992 because of overcrowding concerns. The facility was severely damage ...

in Nashville

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

. Arwood was the last federal inmate executed under the administration of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

.

Early life

James Clyde Arwood was born inRipley, Tennessee

Ripley is a city in Lauderdale County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 8,445 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Lauderdale County.

Geography

Ripley is located at (35.743115, −89.533872).

According to the United States ...

, on September 7, 1901, to James Monroe Arwood and Dora Arwood (née

The birth name is the name of the person given upon their birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name or to the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a births registe ...

Akin). According to his death certificate, Arwood was employed as a barber. He was married to Bessie Arwood, although they divorced sometime before his execution.

Murder of J.W. Lunsford

On August 2, 1931, Deputy Sheriffs James Wyatt Lunsford and C.A. Borders went to the home of Arwood's brother, Cornelius Arwood, near Ripley, Tennessee, following a report that Clyde Arwood had beaten Cornelius's wife severely enough to break her arm in retaliation for her not giving him a pistol. At the time, Arwood was heavily intoxicated. Lunsford and Borders attempted to arrest Arwood, but Arwood resisted arrest. After some time, Arwood agreed to speak to Lunsford, but as Lunsford approached him, Arwood shot him with a shotgun. Lunsford remained in the hospital for several days, during which his left arm developedgangrene

Gangrene is a type of tissue death caused by a lack of blood supply. Symptoms may include a change in skin color to red or black, numbness, swelling, pain, skin breakdown, and coolness. The feet and hands are most commonly affected. If the ga ...

and had to be amputated

Amputation is the removal of a limb or other body part by trauma, medical illness, or surgery. As a surgical measure, it is used to control pain or a disease process in the affected limb, such as malignancy or gangrene. In some cases, it is ...

. On Wednesday, August 5, Lunsford died from his injuries.

Arwood was arrested for Lunsford's death and held in the Lauderdale County Jail. He was charged with Lunsford's murder on Thursday, August 6. On June 28, 1932, Arwood was convicted of Lunsford's murder and sentenced to 21 years in state prison. On August 24, 1938, Governor Gordon Browning commuted Arwood's sentence to 10–20 years in prison, and he was released on parole

Parole, also known as provisional release, supervised release, or being on paper, is a form of early release of a prisoner, prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated ...

effective that day. Arwood violated his parole about a year later, leading to his return to prison on either August 31 or October 31, 1939, but he was paroled again on February 16, 1940. Around the time of Arwood's execution, Lunsford was repeatedly misidentified in newspapers as "Wyde Lunsford."

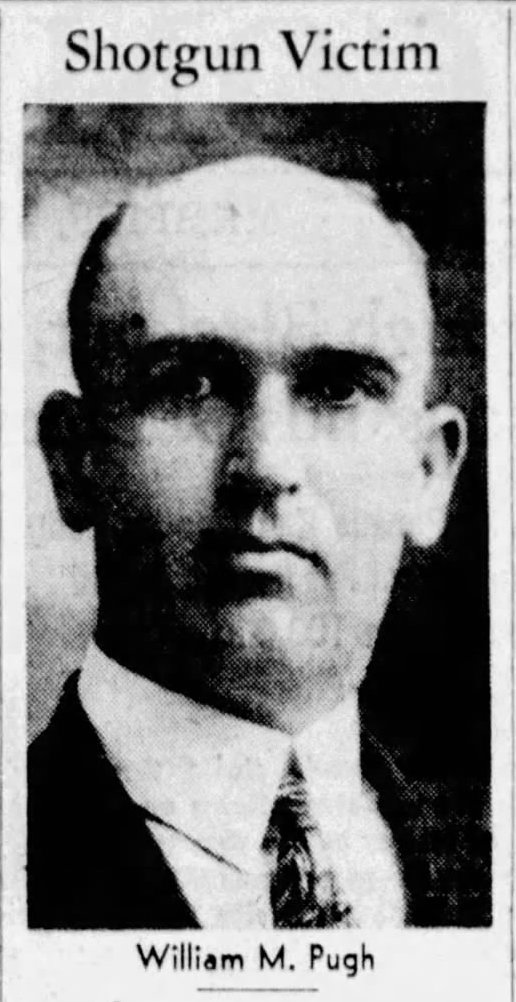

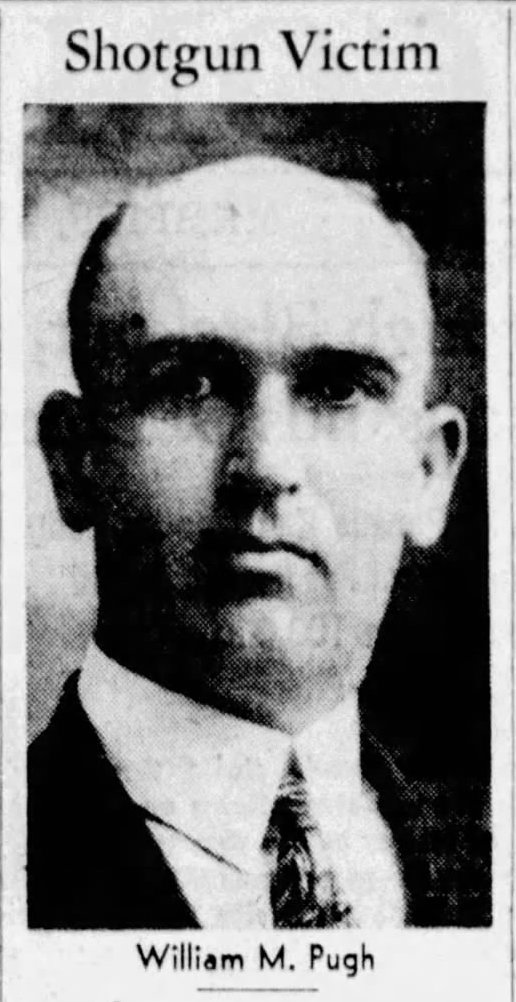

Murder of federal agent William Pugh

Following Arwood's parole, Arwood moved back to Lauderdale County and began operating an illegal

Following Arwood's parole, Arwood moved back to Lauderdale County and began operating an illegal still

A still is an apparatus used to distillation, distill liquid mixtures by heating to selectively Boiling, boil and then cooling to Condensation, condense the vapor. A still uses the same concepts as a basic Distillation#Laboratory_procedures, ...

, where he manufactured moonshine

Moonshine is alcohol proof, high-proof liquor, traditionally made or distributed alcohol law, illegally. The name was derived from a tradition of distilling the alcohol (drug), alcohol at night to avoid detection. In the first decades of the ...

. Approximately one year later, on November 21, 1941, federal agents arrived at Arwood's home in west Lauderdale County, Tennessee

Lauderdale County is a county located on the western edge of the U.S. state of Tennessee, with its border the Mississippi River. As of the 2020 census, the population was 25,143. Its county seat is Ripley. Since the antebellum years, it has b ...

, to arrest him for operating an unlicensed still. Before completing the arrest, Arwood requested to go back inside his house so he could bid farewell to his aged mother. Authorities allowed him to go back inside. Arwood reemerged from his house with a shotgun. He fired at William M. Pugh, a federal alcohol tax unit investigator and former federal prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic b ...

agent from Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in Shelby County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Situated along the Mississippi River, it had a population of 633,104 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Tenne ...

, and struck Pugh point-blank

Point-blank range is any distance over which a certain firearm or gun can hit a target without the need to elevate the barrel to compensate for bullet drop, i.e. the gun can be pointed horizontally at the target. For targets beyond-blank range ...

in the face. The shotgun wound mortally wounded Pugh, and although emergency medical services were summoned, Pugh died either on the way to the hospital, or within minutes of his arrival.

After the shooting, Arwood fled into the nearby woods, evading detection for hours while a posse searched the woods and swamps for him. Arwood later returned to his house and barricaded himself inside. At approximately 9:30 pm, the posse returned to Arwood's house and found the door locked. Realizing Arwood was inside, the posse opened fire on the house. Arwood fled to the attic as officers in the posse launched tear gas bombs into the house. Eventually, officers in the posse ran out of tear gas bombs and had to retrieve more; as their cars returned at approximately 3:30 am with more tear gas bombs, Arwood surrendered. He had not been injured. An officer later said, "We fired hundreds and hundreds of bullets into the house from all angles and never hit him. How we missed him is more than I can understand. He's a tough man."

Indictment and trial

After his arrest, Arwood was interned in a jail in Shelby County. He was denied bond at a preliminary hearing. Prior to Arwood's case, Tennessee had never seen a federal murder trial. Prior to 1934, only cases involving officers employed with the United StatesInternal Revenue Service

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting Taxation in the United States, U.S. federal taxes and administerin ...

and Customs

Customs is an authority or Government agency, agency in a country responsible for collecting tariffs and for controlling International trade, the flow of goods, including animals, transports, personal effects, and hazardous items, into and out ...

fell under U.S. federal jurisdiction. A new federal law after 1934 allowed cases involving all federal employees to fall under federal jurisdiction, meaning Arwood was eligible to be charged with murder in the West Tennessee Federal Courts, rather than in a state court.

On Friday, November 28, a federal grand jury

A grand jury is a jury empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a person to testify. A grand ju ...

indicted Arwood for the first-degree murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse committed with the necessary intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisdiction. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse ...

of William Pugh and three counts related to operating his illegal still and making illegal mash. The three counts related to the still carried a maximum punishment of six years imprisonment, while the first-degree murder charge carried a mandatory death sentence

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

. After Arwood plea

In law, a plea is a defendant's response to a criminal charge. A defendant may plead guilty or not guilty. Depending on jurisdiction, additional pleas may be available, including '' nolo contendere'' (no contest), no case to answer (in the ...

ded not guilty, his trial date was set at January 5, 1942.

Trial

Arwood's trial took place in January 1942 in theUnited States District Court for the Western District of Tennessee

The United States District Court for the Western District of Tennessee (in case citations, W.D. Tenn.) is the federal district court covering the western part of the state of Tennessee. Appeals from the Western District of Tennessee are taken to ...

, in Memphis. Witnesses called to the stand at the trial included other federal agents who were with Pugh before and during the murder, as well as Pugh's widowed wife. One of the federal agents who was with Pugh, James Howes, was the principal witness; he described evidence linking Arwood to the illegal still, including a watch they found which Arwood's mother confirmed as his. Howes also testified to having observed Arwood chopping trees in the nearby woods on an earlier occasion, suggesting Arwood lived near the area. Another federal employee, Howard Taylor, displayed Pugh's daily reports wherein Pugh surmised that Arwood owned the still.

Another witness at the trial was Arwood's 70-year-old mother. During her testimony, Arwood's mother detailed his chronic drunkenness

Alcohol intoxication, commonly described in higher doses as drunkenness or inebriation, and known in overdose as alcohol poisoning, is the behavior and physical effects caused by recent consumption of alcohol. The technical term ''intoxication ...

, alcoholism

Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal. Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World He ...

, and patterns of strange behavior. She also testified that she was in the house in which Arwood barricaded himself after Pugh's murder and that she was almost hit by the gunfire from the posse outside. At one point during her testimony, she collapsed on the stand, prompting Arwood to break down in tears, in contrast to the stoicism he had maintained during the other trial proceedings. The testimony of Arwood's mother, as well as the testimonies of other relatives corroborating Arwood's alcoholism and strange behavior, went towards his defense strategy of entering a plea of temporary insanity, wherein Arwood confessed to murdering Pugh but maintained that he was legally not of sound mind during the killing.

After a three-day trial, the jury rejected Arwood's insanity plea and convicted him of Pugh's murder on January 11, 1942. They did not offer a recommendation that Arwood be given mercy, making a death sentence mandatory. Arwood's attorney, Bailey Walsh, motioned for a new trial; a meeting was therefore scheduled for January 26, 1942, so Arwood's attorneys could argue in favor of a new trial or for a judge to challenge the jury's failure to recommend mercy for Arwood.

During the January 26 hearing, United States federal judge

In the United States, a federal judge is a judge who serves on a court established under Article Three of the U.S. Constitution. Often called "Article III judges", federal judges include the chief justice and associate justices of the U.S. S ...

Marion Speed Boyd rejected Arwood's motion for a new trial and formally sentenced Arwood to death. Arwood was reportedly emotionless during his sentencing. The execution was first scheduled to take place on June 1, 1942.

Appeals, imprisonment, and execution

Appeals delayed the execution of Arwood's sentence for approximately one year. After the motion for a new trial was denied and Arwood was formally sentenced to death, he and his attorneys appealed to theUnited States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (in case citations, 6th Cir.) is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts in the following districts:

* Eastern District of Kentucky

* Western District of K ...

. By a 2–1 vote, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Arwood's conviction and death sentence, with Judges Xen Hicks and Florence E. Allen affirming. The lone dissent came from Judge Elwood Hamilton, who questioned Pugh's authority to be on Arwood's property at the time, as well as Pugh's authority to conduct the arrest preceding his murder.

Until shortly before the execution was to take place, Arwood was housed at the Shelby County Jail; afterwards, he was transported to the Tennessee State Penitentiary

Tennessee State Prison is a former correctional facility located six miles west of downtown Nashville, Tennessee on Cockrill Bend. It opened in 1898 and has been closed since 1992 because of overcrowding concerns. The facility was severely damage ...

in Nashville

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

, where Tennessee's execution chamber

An execution chamber, or death chamber, is a room or chamber in which capital punishment is carried out. Execution chambers are almost always inside the walls of a prison#Security levels, maximum-security prison, although not always at the same p ...

was located at the time.

Arwood personally wrote to U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt ( ; October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the longest-serving First Lady of the United States, first lady of the United States, during her husband Franklin D ...

requesting clemency

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

and a commutation

Commute, commutation or commutative may refer to:

* Commuting, the process of travelling between a place of residence and a place of work

Mathematics

* Commutative property, a property of a mathematical operation whose result is insensitive to th ...

of his death sentence. Weeks prior to the execution, U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle

Francis Beverley Biddle (May 9, 1886 – October 4, 1968) was an American lawyer and judge who was the United States Attorney General during World War II. He also served as the primary American judge during Nuremberg trials following World War I ...

informed Arwood that President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

had denied clemency, allowing the execution to move forward.

Tennessee State Penitentiary Warden

A warden is a custodian, defender, or guardian. Warden is often used in the sense of a watchman or guardian, as in a prison warden. It can also refer to a chief or head official, as in the Warden of the Mint.

''Warden'' is etymologically ident ...

Thomas P. Gore described Arwood as a good prisoner and that Arwood made very few requests during his time on death row, only asking for a daily copy of the local newspaper so he could keep up with World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

news. He also requested that his civilian clothes be given to his brothers following his execution, opting to wear prison garb instead. Arwood spent his last minutes with his brothers, who departed only a few minutes before the execution took place.

Arwood walked to the execution chamber at 5:30 a.m., and he was strapped into the electric chair

The electric chair is a specialized device used for capital punishment through electrocution. The condemned is strapped to a custom wooden chair and electrocuted via electrodes attached to the head and leg. Alfred P. Southwick, a Buffalo, New Yo ...

at 5:35 a.m. After walking into the execution chamber, Arwood said, "Goodbye, friends." When asked for a formal final statement, Arwood only replied, "That's all." The prison physician pronounced him dead five minutes later, at 5:40 a.m. The execution was supervised by Charles W. Miles, the United States Marshal

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The Marshals Service serves as the enforcement and security arm of the United States federal judi ...

for the western district of Tennessee, who was assisted by Tennessee State Penitentiary Deputy Warden Glenn Swafford.

See also

*Capital punishment by the United States federal government

Capital punishment is a legal punishment under the criminal justice system of the United States federal government. It is the most serious punishment that could be imposed under federal law. The serious crimes that warrant this punishment inc ...

* List of people executed by the United States federal government

The following is a list of people executed by the United States federal government.

Post-''Gregg'' executions

Sixteen executions (none of them military) have occurred in the modern post-''Gregg'' era. Since 1976, sixteen people have been execu ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Arwood, Clyde 1901 births 1943 deaths 20th-century executions by the United States federal government 20th-century executions of American people 20th-century American murderers American people executed for murdering police officers People from Ripley, Tennessee People convicted of murder by Tennessee People convicted of murder by the United States federal government People executed by the United States federal government by electric chair Recipients of American gubernatorial clemency