Club Harlem on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Club Harlem was a

In July 1940, Club Harlem, Little Belmont, the Paradise Club, and the

In July 1940, Club Harlem, Little Belmont, the Paradise Club, and the

nightclub

A nightclub or dance club is a club that is open at night, usually for drinking, dancing and other entertainment. Nightclubs often have a Bar (establishment), bar and discotheque (usually simply known as disco) with a dance floor, laser lighti ...

at 32 North Kentucky Avenue in the Northside neighborhood of Atlantic City, New Jersey

Atlantic City, sometimes referred to by its initials A.C., is a Jersey Shore seaside resort city (New Jersey), city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, Atlantic County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.

Atlantic City comprises the second half of ...

. Founded in 1935 by Leroy "Pop" Williams, it was the city's premier club for black jazz performers. Like its Harlem counterpart, the Cotton Club

The Cotton Club was a 20th-century nightclub in New York City. It was located on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue from 1923 to 1936, then briefly in the midtown Theater District until 1940. The club operated during the United States' era of P ...

, many of Club Harlem's guests were white, wealthy and eager to experience a night of African-American entertainment.

An elaborate all-black revue

A revue is a type of multi-act popular theatre, theatrical entertainment that combines music, dance, and sketch comedy, sketches. The revue has its roots in 19th century popular entertainment and melodrama but grew into a substantial cultural pre ...

called ''Smart Affairs'', produced by Larry Steele

Larry Nelson Steele (born May 5, 1949) is a former professional basketball player, best known for being on the Portland Trail Blazers team that won the 1977 NBA Finals.

Early life

Born in Greencastle, Indiana, Steele grew up in Bainbridge, ...

and headquartered at the club from 1946 to 1971, featured 40 to 50 acts and was on a par with Broadway productions. Performers at the club included Sammy Davis Jr.

Samuel George Davis Jr. (December 8, 1925 – May 16, 1990) was an American singer, actor, comedian, dancer, and musician.

At age two, Davis began his career in Vaudeville with his father Sammy Davis Sr. and the Will Mastin Trio, which t ...

(who would also invite the white members of the Rat Pack

The Rat Pack was an informal group of singers that, in its second iteration, ultimately made films and appeared together in Las Vegas casino venues. They originated in the late 1940s and early 1950s as a group of A-list show business friends, s ...

), Dick Gregory

Richard Claxton Gregory (October 12, 1932 – August 19, 2017) was an American comedian, actor, writer, activist and social critic. His books were bestsellers. Gregory became popular among the African-American communities in the southern U ...

, Dinah Washington

Dinah Washington (; born Ruth Lee Jones; August 29, 1924 – December 14, 1963) was an American singer and pianist, one of the most popular black female recording artists of the 1950s. Primarily a jazz vocalist, she performed and recorded in a ...

, Bootsie Barnes

Robert "Bootsie" Barnes (November 27, 1937 – April 22, 2020) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist from Philadelphia.

Early life and education

Barnes was raised in a housing project in North Philadelphia. His father was a trumpet player wh ...

, Gladys Knight

Gladys Maria Knight (born May 28, 1944) is an American singer and actress. Knight recorded hits through the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s with her family group Gladys Knight & the Pips, which included her brother Merald "Bubba" Knight and cousins Will ...

, Teddy Pendegrass, Hot Lips Page

Oran Thaddeus "Hot Lips" Page (January 27, 1908 – November 5, 1954) was an American jazz trumpeter, singer, and bandleader. He was known as a scorching soloist and powerful vocalist.

Page was a member of Walter Page's Blue Devils, Artie Sh ...

, and Wild Bill Davis

Wild Bill Davis (November 24, 1918 – August 17, 1995) was the stage name of American jazz pianist, organist, and arranger William Strethen Davis. He is best known for his pioneering jazz electric organ recordings and for his tenure with t ...

. Drummer Crazy Chris Columbo conducted the club orchestra for 34 years. Club Harlem was outfitted with seven bars, two lounges and a main showroom seating more than 900. A cocktail lounge had room for 400 guests with continuous entertainment available.

Club Harlem was the site of the 1972 Easter morning shootout of a Black Mafia

The Black Mafia, also known as the Philadelphia Black Mafia (PBM), Black Muslim Mafia and Muslim Mob, was a Philadelphia-based African-American organized crime syndicate. The organization began in the 1960s as a relatively small criminal colle ...

operative by three rival operatives, leaving five dead and 20 wounded, in full view of a show audience estimated at 600 people. The club closed in 1986 and was demolished in 1992. Mementos salvaged from the club are part of a traveling exhibition which has appeared in Atlantic City and other locales since 2010.

History

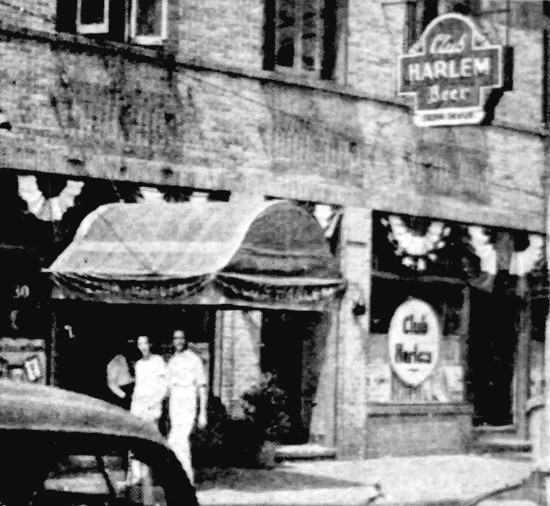

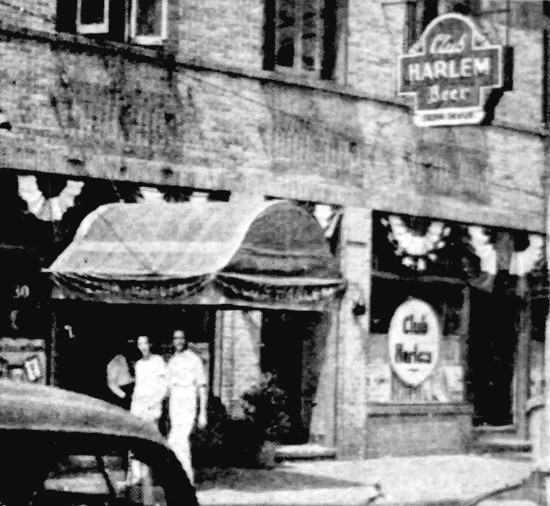

Club Harlem was founded in 1935 by Leroy "Pop" Williams on the site of a dance hall called Fitzgerald's Auditorium. Williams was a medical student atUniversity of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. One of nine colonial colleges, it was chartered in 1755 through the efforts of f ...

when he managed to acquire enough money to buy Fitzgerald's; he left college after becoming the owner of the nightclub. Williams gave the new nightclub the name of the Manhattan neighborhood because "a lot of black people live there". The district, known as "Kentucky Avenue and the Curb", had become the home for African Americans in the racially segregated city since the end of World War I. The new nightspot joined other popular black entertainment venues in the district such as Grace's Little Belmont

Grace's Little Belmont was a jazz music bar and lounge in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Located at 37 North Kentucky Avenue, it was one of the four popular black nightclubs situated on that street between the mid-1930s and mid-1970s; the others were C ...

, the Wintergarten, and the Paradise Club. Along with Harlem's Cotton Club

The Cotton Club was a 20th-century nightclub in New York City. It was located on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue from 1923 to 1936, then briefly in the midtown Theater District until 1940. The club operated during the United States' era of P ...

, it was a place for the moneyed set to enjoy an evening of African-American entertainment. When the club opened in 1935, there were slot machines along with a basketball court on the top floor of the building. In the 1940s the club became known as Clifton's Club Harlem.

In July 1940, Club Harlem, Little Belmont, the Paradise Club, and the

In July 1940, Club Harlem, Little Belmont, the Paradise Club, and the Wonder Bar

''Wonder Bar'' is a 1934 American film adaptation of a Broadway musical of the same name directed by Lloyd Bacon with musical numbers created by Busby Berkeley.

It stars Al Jolson, Kay Francis, Dolores del Río, Ricardo Cortez, Dick Pow ...

were targeted in a midnight raid by police officers, accompanied by the newly elected mayor, Tom Taggart, seeking proof of illegal gambling activities. The police confiscated "three truckloads of gambling paraphernalia" and arrested 32 club owners and employees, then shut down the four clubs. The next day the clubs were open for business as usual.

In 1947, showman Larry Steele

Larry Nelson Steele (born May 5, 1949) is a former professional basketball player, best known for being on the Portland Trail Blazers team that won the 1977 NBA Finals.

Early life

Born in Greencastle, Indiana, Steele grew up in Bainbridge, ...

introduced an all-black revue called ''Smart Affairs'' to Club Harlem. The elaborate show, featuring 40 to 50 acts including comedians, singers, showgirls, chorus lines, and dance numbers, was headquartered at the club through 1970, and also toured throughout the United States and abroad between the 1940s and 1960s, including venues in San Juan, Puerto Rico

San Juan ( , ; Spanish for "Saint John the Baptist, John") is the capital city and most populous Municipalities of Puerto Rico, municipality in the Commonwealth (U.S. insular area), Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the ...

, Adelaide, Australia

Adelaide ( , ; ) is the list of Australian capital cities, capital and most populous city of South Australia, as well as the list of cities in Australia by population, fifth-most populous city in Australia. The name "Adelaide" may refer to ei ...

, and Toronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

, Canada. The budget for the "Smart Affairs" shows ran as high as US$35,000 per week. The shows were on a par with Broadway productions. ''Smart Affairs'' productions grossed between $400,000 and $500,000 annually by the early 1960s. Steele also founded the Sepia Revue and Beige Beauties chorus lines at the club. Entertainer Lola Falana

Loletha Elayne Falana or Loletha Elaine Falana (born September 11, 1942), better known by her stage name Lola Falana, is an American singer, dancer, and actress. She was nominated for the Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical in 1975 for her ...

was discovered by Sammy Davis, Jr. while working in Club Harlem's chorus line.

In 1951 Williams and his brother, Clifton Williams, brought in other partners, including Ben Alten of the Paradise Club. By 1954, Williams and Alten owned the Club Harlem and the Paradise Club, operating both under joint ownership. The club employed 200 people in 1964. Its busiest time was during the tourist season from mid June to Labor Day

Labor Day is a Federal holidays in the United States, federal holiday in the United States celebrated on the first Monday of September to honor and recognize the Labor history of the United States, American labor movement and the works and con ...

. Alten described the club's most profitable time as being between 1959 and 1977. On the weekends, between 20 and 25 buses from areas in the Northeastern United States

The Northeastern United States (also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast) is List of regions of the United States, census regions United States Census Bureau. Located on the East Coast of the United States, ...

arrived, bringing guests who wanted to see the club's shows.

By 1968, Williams began having difficulty booking some African-American entertainers into the venue. He wrote an open letter to baseball star Jackie Robinson

Jack Roosevelt Robinson (January 31, 1919 – October 24, 1972) was an American professional baseball player who became the first Black American to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) in the modern era. Robinson broke the Baseball color line, ...

, who had a regular column in the ''Pittsburgh Courier

The ''Pittsburgh Courier'' was an African American weekly newspaper published in Pittsburgh from 1907 until October 22, 1966. By the 1930s, the ''Courier'' was one of the leading black newspapers in the United States.

It was acquired in 1965 by ...

'' newspaper. The entertainers in question did not want to work at venues catering to African Americans. After the death of Pop Williams in 1976, Alten's new business partner was businessman Calvin Brock. Alten and Brock refurbished the club, but business was never as good as it had been in the past.

Description

Club Harlem was outfitted with two lounges and a main showroom seating more than 900. A cocktail lounge had room for 400 guests, with continuous entertainment available. The club was equipped with seven bars; the front bar alone accommodated nearly 100 people. GuitaristPat Martino

Pat Martino (born Patrick Carmen Azzara; August 25, 1944 – November 1, 2021) was an American jazz guitarist and composer. He has been cited as one of the greatest guitarists in jazz.

Early life

Martino was born Patrick Carmen Azzara in Philad ...

recalled in his biography: "In the front room at Club Harlem you had two stages for two different groups. Willis Jackson would do forty minutes, and then Chris Columbo's band would do forty minutes. They'd split sets all night long. And in the large back room you had singers like Sammy Davis with an orchestra. That was an incredible place." Weekends at Club Harlem started on Friday night, with the two bands alternating sets; the music kept going until Monday morning.

Shows

The club scheduled matinees, nighttime shows, late-night shows, and a 6 a.m. "breakfast show" during the summer tourist season. The music played from 10 p.m. Saturday night to 6 a.m. Monday morning. "Celebrities, politicians, and tourists" often arrived in the early morning hours after the clubs on the white side of town had closed, and white performers such asFrank Sinatra

Francis Albert Sinatra (; December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998) was an American singer and actor. Honorific nicknames in popular music, Nicknamed the "Chairman of the Board" and "Ol' Blue Eyes", he is regarded as one of the Time 100: The Most I ...

, Milton Berle

Milton Berle (born Mendel Berlinger; ; July 12, 1908 – March 27, 2002) was an American actor and comedian. His career as an entertainer spanned over eight decades, first in silent films and on stage as a child actor, then in radio, movies and ...

, and Lenny Bruce

Leonard Alfred Schneider (October 13, 1925 – August 3, 1966), better known by his stage name Lenny Bruce, was an American stand-up comedian, social critic, and satirist. He was renowned for his open, free-wheeling, and critical style of come ...

would go up on stage.

Top-name black musicians also dropped by "to jam and develop their skills". Musician Kelly Swaggerty, who was with Tadd Dameron

Tadley Ewing Peake Dameron (February 21, 1917 – March 8, 1965) was an American jazz composer, arranger, and pianist.

Biography

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Dameron was the most influential arranger of the bebop era, but also wrote charts for swi ...

's band at the time, remembered a jam session with Clifford Brown

Clifford Benjamin Brown (October 30, 1930 – June 26, 1956) was an American jazz trumpeter, pianist and composer. He died at the age of 25 in a car crash, leaving behind four years' worth of recordings. His compositions "Sandu", "Joy Sprin ...

, Art Farmer

Arthur Stewart Farmer (August 21, 1928 – October 4, 1999) was an American jazz trumpeter and flugelhorn player. He also played flumpet, a trumpet–flugelhorn combination especially designed for him. He and his identical twin brother, doub ...

and Joe Gordon

Joseph Lowell Gordon (February 18, 1915 – April 14, 1978), nicknamed "Flash", in reference to the comic-book character '' Flash Gordon'', was an American second baseman, coach and manager in Major League Baseball who played for the New York Y ...

that began at the Paradise Club and was continued at Club Harlem as the musicians wanted to continue playing. Long-time Atlantic City disc jockey Pinky Kravitz recalled that by 3 a.m., there were up to 1,000 people in line, waiting for the breakfast show to begin. In addition to the show itself, any celebrities sitting in the audience were called up to the stage and would perform.

Drummer Chris Columbo, who conducted the club's orchestra for 34 years, remembered that the early morning shows were the most vibrant because the other clubs in town were closed and many of those who were appearing at them were now at Club Harlem jamming with the club's musicians. Johnny Lynch was in charge of the house band of 14 musicians, which was integrated. The band was well regarded among musicians. It was said that if you were in the Club Harlem band for the summer, you were a fine musician. Young men who wanted to become professionals often quit their regular jobs in summer to play with the Lynch band.

The leading black entertainers of the day appeared at Club Harlem, including comedians Dick Gregory

Richard Claxton Gregory (October 12, 1932 – August 19, 2017) was an American comedian, actor, writer, activist and social critic. His books were bestsellers. Gregory became popular among the African-American communities in the southern U ...

, George Kirby

George Kirby (June 8, 1923 – September 30, 1995) was an American comedian, singer, and actor.

Career

Born in Chicago, Kirby broke into show business in the 1940s at the Club DeLisa, a South Side establishment that employed a variety-sho ...

, Moms Mabley

Loretta Mary Aiken (March 19, 1897 – May 23, 1975), known by her stage name Jackie "Moms" Mabley, was an American stand-up comedian and actress. Mabley began her career on the theater stage in the 1920s and became a veteran entertainer of the ...

, and Slappy White

Melvin Edward "Slappy" White (September 27, 1921 – November 7, 1995) was an American comedian and actor. He worked with Redd Foxx on the Chitlin' Circuit of stand-up comedy during the 1950s and 1960s. He appeared on the television shows '' ...

; singers Cab Calloway

Cabell "Cab" Calloway III (December 25, 1907 – November 18, 1994) was an American jazz singer and bandleader. He was a regular performer at the Cotton Club in Harlem, where he became a popular vocalist of the Swing music, swing era. His niche ...

, Billy Daniels

William Boone Daniels (September 12, 1915 – October 7, 1988) was an American singer active in the United States and Europe from the mid-1930s to 1988, notable for his hit recording of " That Old Black Magic" and his pioneering performances on ...

, Billy Eckstine

William Clarence Eckstine (July 8, 1914 – March 8, 1993) was an American jazz and pop singer and a bandleader during the swing and bebop eras. He was noted for his rich, almost operatic bass-baritone voice. In 2019, Eckstine was posthumously a ...

, Ella Fitzgerald

Ella Jane Fitzgerald (April25, 1917June15, 1996) was an American singer, songwriter and composer, sometimes referred to as the "First Lady of Song", "Queen of Jazz", and "Lady Ella". She was noted for her purity of tone, impeccable diction, phra ...

, Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday (born Eleanora Fagan; April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959) was an American jazz and swing music singer. Nicknamed "Lady Day" by her friend and music partner, Lester Young, Holiday made significant contributions to jazz music and pop ...

, Lena Horne

Lena Mary Calhoun Horne (June 30, 1917 – May 9, 2010) was an American singer, actress, dancer and civil rights activist. Horne's career spanned more than seventy years and covered film, television and theatre.

Horne joined the chorus of the C ...

, Sarah Vaughan

Sarah Lois Vaughan (, March 27, 1924 – April 3, 1990) was an American jazz singer and pianist. Nicknamed "Sassy" and "List of nicknames of jazz musicians, The Divine One", she won two Grammy Awards, including the Lifetime Achievement Award, ...

, Dinah Washington

Dinah Washington (; born Ruth Lee Jones; August 29, 1924 – December 14, 1963) was an American singer and pianist, one of the most popular black female recording artists of the 1950s. Primarily a jazz vocalist, she performed and recorded in a ...

, and Ethel Waters

Ethel Waters (October 31, 1896 – September 1, 1977) was an American singer and actress. Waters frequently performed jazz, swing, and pop music on the Broadway stage and in concerts. She began her career in the 1920s singing blues. Her no ...

; and jazz musicians Louis Armstrong

Louis Daniel Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971), nicknamed "Satchmo", "Satch", and "Pops", was an American trumpeter and vocalist. He was among the most influential figures in jazz. His career spanned five decades and several era ...

, Count Basie

William James "Count" Basie (; August 21, 1904 – April 26, 1984) was an American jazz pianist, organist, bandleader, and composer. In 1935, he formed the Count Basie Orchestra, and in 1936 took them to Chicago for a long engagement and the ...

, Nat King Cole

Nathaniel Adams Coles (March 17, 1919 – February 15, 1965), known professionally as Nat King Cole, alternatively billed as Nat "King" Cole, was an American singer, jazz pianist, and actor. Cole's career as a jazz and Traditional pop, pop ...

, Wild Bill Davis

Wild Bill Davis (November 24, 1918 – August 17, 1995) was the stage name of American jazz pianist, organist, and arranger William Strethen Davis. He is best known for his pioneering jazz electric organ recordings and for his tenure with t ...

, and Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American Jazz piano, jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous Big band, jazz orchestra from 1924 through the rest of his life.

Born and raised in Washington, D ...

. Daniels first performed his signature song

A signature (; from , "to sign") is a depiction of someone's name, nickname, or even a simple "X" or other mark that a person writes on documents as a proof of identity and intent. Signatures are often, but not always, handwritten or styliz ...

"That Old Black Magic

"That Old Black Magic" is a 1942 popular song written by Harold Arlen (music), with the lyrics by Johnny Mercer. They wrote it for the 1942 film '' Star Spangled Rhythm'', when it was first sung by Johnny Johnston and danced by Vera Zorina. Th ...

" at Club Harlem in 1942. Guitarist Pat Martino

Pat Martino (born Patrick Carmen Azzara; August 25, 1944 – November 1, 2021) was an American jazz guitarist and composer. He has been cited as one of the greatest guitarists in jazz.

Early life

Martino was born Patrick Carmen Azzara in Philad ...

has stated that as a younger man he would play at Smalls Paradise

Smalls Paradise (often called Small's Paradise and Smalls' Paradise), was a nightclub in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. Located in the basement of 2294 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard at 134th Street, it opened in 1925 ...

in New York City for six months and then perform in the summer at the Club Harlem. Racism, however, prohibited many of these performers from appearing at clubs on the south side of town, where white families lived. However, in the 1950s Frank Sinatra came from the 500 Club

The 500 Club, popularly known as The Five, was a nightclub and supper club at 6 South Missouri Avenue in Atlantic City, New Jersey, United States. It was owned by racketeer Paul "Skinny" D'Amato, and operated from the 1930s until the building b ...

to Club Harlem to perform with Sammy Davis, Jr., and sang with Davis, a member of the Rat Pack

The Rat Pack was an informal group of singers that, in its second iteration, ultimately made films and appeared together in Las Vegas casino venues. They originated in the late 1940s and early 1950s as a group of A-list show business friends, s ...

, back at the 500 Club. Lonnie Smith recorded a live album, ''Move Your Hand

''Move Your Hand'' is a live album by American organist Lonnie Smith recorded at Club Harlem in Atlantic City, New Jersey in 1969 and released on the Blue Note label.

'', at Club Harlem in 1969. Even in its waning years in the 1970s, Club Harlem continued to attract contemporary black stars such as Harry Belafonte

Harry Belafonte ( ; born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr.; March 1, 1927 – April 25, 2023) was an American singer, actor, and civil rights activist who popularized calypso music with international audiences in the 1950s and 1960s. Belafonte ...

, Ray Charles

Ray Charles Robinson (September 23, 1930 – June 10, 2004) was an American singer, songwriter, and pianist. He is regarded as one of the most iconic and influential musicians in history, and was often referred to by contemporaries as "The Gen ...

, Aretha Franklin

Aretha Louise Franklin ( ; March 25, 1942 – August 16, 2018) was an American singer, songwriter and pianist. Honored as the "Honorific nicknames in popular music, Queen of Soul", she was twice named by ''Rolling Stone'' magazine as the Roll ...

, Redd Foxx

John Elroy Sanford (December 9, 1922 – October 11, 1991), better known by his stage name Redd Foxx, was an American stand-up comedian and actor. Foxx gained success with his raunchy nightclub act before and during the civil rights movemen ...

, Marvin Gaye

Marvin Pentz Gaye Jr. (; April 2, 1939 – April 1, 1984) was an American Rhythm and blues, R&B and soul singer, songwriter, musician, and record producer. He helped shape the sound of Motown in the 1960s, first as an in-house session player an ...

, Leslie Uggams

Leslie Marian Uggams (; born May 25, 1943) is an American actress and singer. After beginning her career as a child in the early 1950s, she garnered acclaim for her role in the Broadway theatre, Broadway musical ''Hallelujah, Baby!'', winning a T ...

, and Dionne Warwick

Marie Dionne Warwick ( ; born Marie Dionne Warrick; December 12, 1940) is an American singer, actress, and television host. During her career, Warwick has won many awards, including six Grammy Awards. She has been inducted into the Hollywood Wa ...

.

The shows at the club were choreographed by Larry Steele for many years, along with those of the nearby Paradise Club, and often featured "comedians dressed like clowns, plantation hands, and frumpy old ladies elling

''Elling'' is a Norwegian Black comedy film directed by Petter Næss. Shot mostly in and around the Norwegian capital Oslo, the film, which was released in 2001, is primarily based on Ingvar Ambjørnsen's novel ''Brødre i blodet'' ("Blood bro ...

dirty jokes to start things off". A full chorus line

A chorus line is a large group of dancers who together perform synchronized routines, usually in musical theatre. Sometimes, singing is also performed. While synchronized dancing indicative of a chorus line was vogue during the first half of th ...

called the Sepia Revue featured 12 showgirls dressed in "black high heels, skimpy, sequined dresses, long boas and feathered headgear" dancing with more and more abandon as the "red hot" house band backed them up. Another chorus line called Beige Beauties also performed artistic dance numbers. There was no applause at the club. Guests found long wooden sticks with wooden balls at the end called "table knockers" at their tables. Patrons were to hit the table with their knockers to indicate their appreciation of performances.

Not long after its closing, Alten, an owner of the club for 35 years, reminisced about the performers who brought the most guests to the club. He named Gladys Knight & the Pips

Gladys Knight & the Pips were an American Rhythm and blues, R&B, soul music, soul, and funk family music group from Atlanta, Georgia, that remained active on the music charts and performing circuit for over three decades starting from the early ...

and Sam Cooke

Samuel Cooke (; January 22, 1931 – December 11, 1964) was an American singer and songwriter. Considered one of the most influential soul music, soul artists of all time, Cooke is commonly referred to as the "King of Soul" for his distin ...

as the two acts who brought the most business into Club Harlem. Alten said the club prevented fights when Sam Cooke performed there by using "Sold Out" signs, which got people to leave without trying to fight to get into the performances.

In the offseason, the club accommodated community fundraisers and teen talent shows.

Final years and demolition

Club Harlem was the site of the 1972 Easter morning assassination of theBlack Mafia

The Black Mafia, also known as the Philadelphia Black Mafia (PBM), Black Muslim Mafia and Muslim Mob, was a Philadelphia-based African-American organized crime syndicate. The organization began in the 1960s as a relatively small criminal colle ...

's "Fat" Tyrone Palmer, in full view of a show audience estimated at 600 people. Four rival operatives entered the club and one shot Palmer in the face after the featured singer, Billy Paul

Paul Williams (December 1, 1934 – April 24, 2016), known professionally as Billy Paul, was an American soul music, soul singer, known for his 1972 Record chart, No. 1 single "Me and Mrs. Jones". His 1973 album and single ''War of the Gods (alb ...

, finished his opening song. Palmer's bodyguard and three women were killed in the melee that ensued, and 20 people were injured. Business dropped off after that.

The club went into a steep decline between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s as the introduction of casino gambling on the Atlantic City Boardwalk pulled business away from Club Harlem and other nightspots located streetside. In the winter of 1986 it was purchased by a developer for $200,000–well below its valuation of $673,000–and shuttered; it had last opened for two weeks in the summer of 1986; it was the last of Atlantic City's major golden age nightclubs still in operation. When the club closed for good, owner Alten made it clear that the closing was not due to unpaid bills; he referred to it as "going out with its face up". There had been an effort to sell the property for some years. After the sale, many people expressed a wish to save Club Harlem. Atlantic City's mayor at the time, James Usry, was among those who wanted to preserve the club and took part in a private effort to do so.

In December 1992 a nor'easter

A nor'easter (also northeaster; see below) is a large-scale extratropical cyclone in the western North Atlantic Ocean. The name derives from the direction of the winds that blow from the northeast. Typically, such storms originate as a low ...

struck the building, and the building was torn down. Fans retrieved the interior furnishings and vintage photographs before the demolition in the hopes of displaying them in a future museum. A historical marker on Kentucky Avenue commemorates Club Harlem. The building site is now a parking lot where the Kentucky Avenue Renaissance Festival

Kentucky Avenue Renaissance Festival, also known as the Historical Kentucky Avenue Renaissance Festival, is a street fair held each summer in the former black entertainment district of Atlantic City, New Jersey. Founded in 1992, it appeared annuall ...

is held each summer.

Legacy

The African American Heritage Museum of Southern New Jersey, founded by Ralph Hunter, and the Noyes Arts Garage atStockton University

Stockton University is a public university in Galloway Township, New Jersey. It is part of New Jersey's public system of higher education. It is named for Richard Stockton, one of the New Jersey signers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence ...

are in possession of the mementos rescued from the club, including "costumes, posters, ashtrays, the neon sign", and a set of red padded leather double doors illustrated with full-size drawings of Pop Williams and Sammy Davis Jr. The museum has lent the artifacts to a traveling exhibition that appeared at the Atlantic City Public Library in 2010 under the name "A Pictorial of Club Harlem and the Way We Were". The collection, along with more than 100 historical photographs and newspaper articles, has also traveled to Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

, and Newark.

''On Kentucky Avenue – The Atlantic City Club Harlem Revue'', created by Adam

Adam is the name given in Genesis 1–5 to the first human. Adam is the first human-being aware of God, and features as such in various belief systems (including Judaism, Christianity, Gnosticism and Islam).

According to Christianity, Adam ...

and Jeree Wade, who each performed at Club Harlem in different decades, made its New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

debut during Black History Month

Black History Month is an annually observed commemorative month originating in the United States, where it is also known as African-American History Month. It began as a way of remembering important people and events in the history of the Af ...

2013. It plays every few months at Stage 72

The Triad Theater, formerly known as Palsson's Supper Club, Steve McGraw's, and Stage 72, is a cabaret-style performing arts venue located on West 72nd Street on New York's Upper West Side. The theatre has been the original home to some of the lon ...

.

The club served as one of the filming locations for the 1980 film ''Atlantic City

Atlantic City, sometimes referred to by its initials A.C., is a Jersey Shore seaside resort city in Atlantic County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.

Atlantic City comprises the second half of the Atlantic City- Hammonton metropolitan sta ...

''.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * {{cite book, url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2kvfCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA98, title=Tappin' at the Apollo: The African American Female Tap Dance Duo Salt and Pepper, first=Cheryl M., last=Willis, year=2016, publisher=McFarland, isbn=978-1-4766-2315-3 Jazz clubs in Atlantic City, New Jersey Nightclubs in Atlantic City, New Jersey Defunct jazz clubs in New Jersey 1935 establishments in New Jersey 1986 disestablishments in New Jersey Buildings and structures demolished in 1992 Demolished buildings and structures in New Jersey African-American history of New Jersey