Clive Gallop on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Colonel Reginald Clive Gallop (4 February 1892 – 7 September 1960 Martin Pugh, 'Bentley Boys (act. 1919–1931)’, ''

From 1921, Gallop joined "Count"

From 1921, Gallop joined "Count"

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

'', Oxford University Press, May 2013) was a British engineer, racing driver and First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

pilot. He was one of the team which developed their first engine for Bentley Motors.

Royal Flying Corps

Clive Gallop joined theRoyal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC sup ...

, flying aeroplanes over the Western Front. He commanded a number of flights, including No. 56 Squadron.

London racing driver, motor vehicle dealer and engineer W. O. Bentley had suggested aluminium pistons to his car supplier Doriot, Flandrin & Parant and had them installed in those cars he imported. Following commissioning on the outbreak of war as an engineer by the Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty (United Kingdom), Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British ...

Bentley was sent to Gwynnes pumps workshops in Chiswick

Chiswick ( ) is a district in West London, split between the London Borough of Hounslow, London Boroughs of Hounslow and London Borough of Ealing, Ealing. It contains Hogarth's House, the former residence of the 18th-century English artist Wi ...

which were making French Clerget engines under license. Part of Bentley's duties was to liaise between the squadrons in the field in France and the factory's engineering staff which is how he came to meet Gallop.W. O. Bentley ''My Life and My Cars'', 1967, London, Hutchinson & Co Clerget was very unwilling to act on Bentley's more important suggestions so the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

sent Bentley to Humber Limited in Coventry

Coventry ( or rarely ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands county, in England, on the River Sherbourne. Coventry had been a large settlement for centurie ...

.

At Humber, Bentley was given a team to design his own aero-engine. The resulting engine, fundamentally different from the Clerget though—for ease of production—alike in the design of the cam mechanism, was running in prototype by early summer 1916. This was the BR1, ''Bentley Rotary 1'', with the bigger BR2 followed in early 1918. Gallop helped Bentley bring both into service with the Royal Flying Corps.

At the end of hostilities and leaving his commission with the Royal Flying Squadron, Gallop joined the Royal Aero Club

The Royal Aero Club (RAeC) is the national co-ordinating body for air sport in the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1901 as the Aero Club of Great Britain, being granted the title of the "Royal Aero Club" in 1910.

History

The Aero Club was foun ...

.

Bentley Motors

In 1919, a group was formed inCricklewood

Cricklewood is a town in North London, England, in the London Boroughs of Camden, Barnet, and Brent. The Crown pub, now the Clayton Crown Hotel, is a local landmark and lies north-west of Charing Cross.

Cricklewood was a small rural hamlet ...

by W O Bentley, a motor vehicles engine designer, pioneer of aluminum pistons who had turned in wartime to aero engines, to build his own cars. With a group including Frederick Tasker Burgess, formerly of Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Trent, Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms ...

, and Harry Varley, formerly of Vauxhall

Vauxhall ( , ) is an area of South London, within the London Borough of Lambeth. Named after a medieval manor called Fox Hall, it became well known for the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens.

From the Victorian period until the mid-20th century, Va ...

, he set about designing a high quality sporting tourer copying a Humber chassis brought there for the purpose.

Gallop joined the team as an engine designer developing the straight-4

A straight-four engine (also referred to as an inline-four engine) is a four-cylinder piston engine where cylinders are arranged in a line along a common crankshaft.

The majority of automotive four-cylinder engines use a straight-four layout ( ...

engine. Although large for its day compared to similar engines from Bugatti

Automobiles Ettore Bugatti was a German then French automotive industry, manufacturer of high performance vehicle, high-performance automobiles. The company was founded in 1909 in the then-German Empire, German city of Molsheim, Alsace, by the ...

, it was its technical innovations that were most noticed. One of the first production engines with 4 valves per cylinder, these were driven by an overhead camshaft

An overhead camshaft (OHC) engine is a piston engine in which the camshaft is located in the cylinder head above the combustion chamber. This contrasts with earlier overhead valve engines (OHV), where the camshaft is located below the combustio ...

. It was also among the first with two spark plug

A spark plug (sometimes, in British English, a sparking plug, and, colloquially, a plug) is a device for delivering electric current from an ignition system to the combustion chamber of a spark-ignition engine to ignite the compressed fuel/air ...

s per cylinder, pent-roof combustion chamber

In engine design, the penta engine (or penta head) is an arrangement of the upper portion of the cylinder and valves that is common in engines using four valves per cylinder.

Design

Among the advantages is a faster burn time of the air-fuel mix ...

s, and twin carburetor

A carburetor (also spelled carburettor or carburetter)

is a device used by a gasoline internal combustion engine to control and mix air and fuel entering the engine. The primary method of adding fuel to the intake air is through the Ventu ...

s. It was extremely undersquare

Stroke ratio, today universally defined as bore/stroke ratio, is a term to describe the ratio between cylinder bore diameter and piston stroke length in a reciprocating piston engine. This can be used for either an internal combustion engine ...

, optimized for low-end torque

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational analogue of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). The symbol for torque is typically \boldsymbol\tau, the lowercase Greek letter ''tau''. Wh ...

, with a bore of and a stroke of . To increase durability, the iron engine block and cylinder head were cast as a single unit.

Power output was roughly , allowing the final Bentley 3 Litre car via a four-speed gearbox to reach . The Speed Model could reach , while the Super Sports passed .

Louis Zborowski

From 1921, Gallop joined "Count"

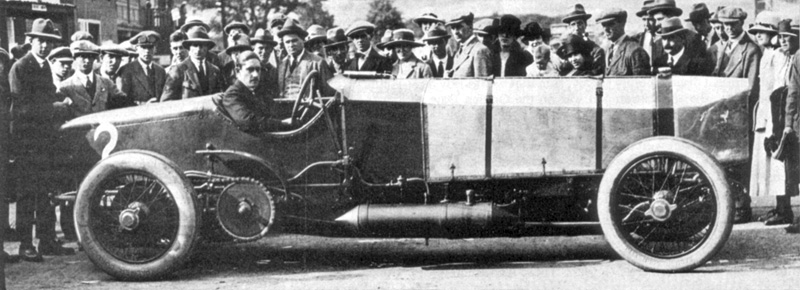

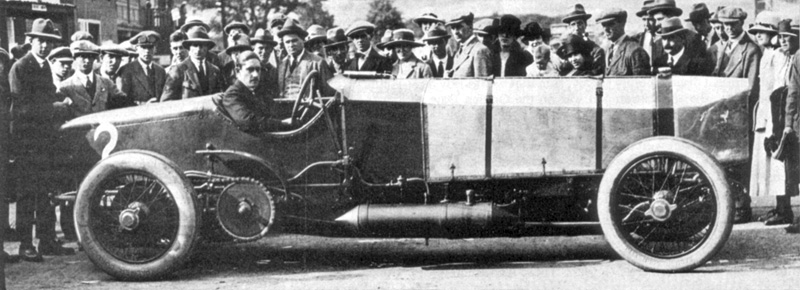

From 1921, Gallop joined "Count" Louis Zborowski

Louis Vorow Zborowski (20 February 1895 – 19 October 1924) was a British racing driver and automobile engineer, best known for creating a series of aero-engined racing cars known as the "Chitty-Bang-Bangs", which provided the inspiration for ...

at his Higham Park estate. As well as acting as his co-driver in numerous races, and as driver of the team's second Aston Martin

Aston Martin Lagonda Global Holdings PLC () is a British manufacturer of Luxury car, luxury sports cars and grand tourers. Its predecessor was founded in 1913 by Lionel Martin and Robert Bamford. Headed from 1947 by David Brown (entrepreneur ...

in others (i.e.: 1922 French Grand Prix

The 1922 French Grand Prix (formally the XVI French Grand Prix, Grand Prix de l'Automobile Club de France) was a Grand Prix motor racing, Grand Prix motor race held at Strasbourg on 15 July 1922. The race was run over 60 laps of the 13.38km circui ...

), he also helped Zborowski design and build four of his own racing cars in the estate's stables.

The first car was powered by a 23,093 cc six-cylinder Maybach aero engine and called " Chitty Bang Bang". A second "Chitty Bang Bang" was powered by 18,882 Benz aero engine. A third car was based on a Mercedes 28/95, but fitted with a 14,778 cc 6-cylinder Mercedes aero engine and was referred to as The White Mercedes. These cars achieved some success at Brooklands.

Another car, also built at Higham Park with a huge 27-litre aero engine, was called the "Higham Special" – later known as " Babs"- and was used in J.G. Parry-Thomas's fatal attempt for the land speed record at Pendine Sands in 1927.

In January 1922 Zborowski, his wife Vi, Gallop and Pixi Marix together with a couple of mechanics took Chitty Bang Bang and the White Mercedes across the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

for a drive into the Sahara Desert

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

, in the tracks of Citroen's kegresse expedition.

In 1923, Zborowski joined with American engineer Harry Arminius Miller, driving the single-seat "American Miller 122" at that year's Italian Grand Prix

The Italian Grand Prix () is the fifth oldest national Grand Prix motor racing, motor racing Grand Prix (after the French Grand Prix, the United States Grand Prix, the Spanish Grand Prix and the Russian Grand Prix), having been held since 1921 ...

. Zborowski died aged 29 the following year whilst racing for Mercedes-Benz in the same race, after hitting a tree.

Bentley Boys

At the end of his partnership with Zborowski in 1924, Gallop as a friend of Woolf Barnato rejoined Bentley Motors in 1925 after his friend bought into the business. This led to him both supporting the racing efforts of the "Bentley Boys", as well as developing the engine for theBentley 4½ Litre

The Bentley 4½ Litre is a British car based on a rolling chassis built by Bentley Motors. Walter Owen Bentley replaced the Bentley 3 Litre with a more powerful car by increasing its engine displacement to . A racing variant was known as the ...

.

Blower Bentley

If Bentley wanted a more powerful car, he developed a bigger capacity model. The Bentley Speed Six was a huge car, which Ettore Bugatti once referred to as "''the world's fastest lorry''" ("Le camion plus vite du monde"). In 1928, Bentley Boy Sir Henry "Tim" Birkin had come to the conclusion that the future lay in getting more power from a lighter model by fitting asupercharger

In an internal combustion engine, a supercharger compresses the intake gas, forcing more air into the engine in order to produce more power for a given displacement (engine), displacement. It is a form of forced induction that is mechanically ...

to the 4½ litre Bentley, refusing to adhere strictly to Bentley's assertion that increasing displacement is always preferable to forced induction

In an internal combustion engine, forced induction is where turbocharging or supercharging is used to increase the density of the intake air. Engines without forced induction are classified as naturally aspirated.

Operating principle Ove ...

. Bentley believed that:

When Bentley Motors refused to create the supercharged model, Birkin determined to develop it himself. Mercedes-Benz

Mercedes-Benz (), commonly referred to simply as Mercedes and occasionally as Benz, is a German automotive brand that was founded in 1926. Mercedes-Benz AG (a subsidiary of the Mercedes-Benz Group, established in 2019) is based in Stuttgart, ...

had been using compressors for a few years.

Development

With financial backing from Dorothy Paget, a wealthy horse racing enthusiast financing the project after his own money had run out, Birkin set-up his own engineering works for the purpose of developing the car atWelwyn Garden City

Welwyn Garden City ( ) is a town in Hertfordshire, England, north of London. It was the second Garden city movement, garden city in England (founded 1920) and one of the first New towns in the United Kingdom, new towns (designated 1948). It is ...

, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and one of the home counties. It borders Bedfordshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the north-east, Essex to the east, Greater London to the ...

.

With an engine and car to be developed by Gallop, Birkin engaged supercharger specialist Amherst Villiers. Gallop had designed the 4½ Litre Bentley engine with a single overhead camshaft

A camshaft is a shaft that contains a row of pointed cams in order to convert rotational motion to reciprocating motion. Camshafts are used in piston engines (to operate the intake and exhaust valves), mechanically controlled ignition syst ...

actuating four valves per cylinder, inclined at 30 degrees, a technically advanced design at a time where most cars still used only two valves per cylinder.

Bentley refused to allow the engine to be modified to incorporate the compressor. The huge Roots

A root is the part of a plant, generally underground, that anchors the plant body, and absorbs and stores water and nutrients.

Root or roots may also refer to:

Art, entertainment, and media

* ''The Root'' (magazine), an online magazine focusin ...

-type supercharger

In an internal combustion engine, a supercharger compresses the intake gas, forcing more air into the engine in order to produce more power for a given displacement (engine), displacement. It is a form of forced induction that is mechanically ...

("blower") was hence added in front of the radiator, driven straight from the crankshaft

A crankshaft is a mechanical component used in a reciprocating engine, piston engine to convert the reciprocating motion into rotational motion. The crankshaft is a rotating Shaft (mechanical engineering), shaft containing one or more crankpins, ...

. This gave the Blower Bentley a unique and easily recognisable profile, and exacerbated its understeer

Understeer and oversteer are vehicle dynamics terms used to describe the sensitivity of the vehicle to changes in steering angle associated with changes in lateral acceleration. This sensitivity is defined for a level road for a given steady state ...

. A guard protected the two carburetters located at the compressor intake. Similar protection was used (both in the 4½ Litre and the Blower) for the fuel tank at the rear, because a flying stone punctured the 3 Litre of Frank Clement and John Duff during the first 24 Hours of Le Mans, possibly depriving them of victory. The crankshaft, pistons and lubrication system were special to the Blower engine.

These additions and modifications took the power of the base car from:

*Unblown: touring model ; racing model .

*Blower: touring model @ 3,500rpm; racing model @ 2,400 rpm.

The " Bentley Blower" was born, more powerful than the 6½ Litre despite lacking the two additional cylinders. The downside was that Blower Bentleys consume 4 liters of fuel per minute at full speed.

Production

The original Bentley Blower No.1 had a taut canvas top stretched over a lightweight Weymann aluminium frame, housing a two-seat body. This presented a very light but still resistant to wind structure. It was officially presented in 1929 at the British International Motor Show at Olympia,London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

.

No. 1 first appeared at the Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

six-hour race at Brooklands on 29 June 1929. However, the car initially proved to be very unreliable. "W.O." had never accepted the blower Bentley, but with effective company owner and financial backer Barnato's support, Birkin persuaded "W.O." to produce the fifty supercharged cars necessary for the model to be accepted for Le Mans.

In addition to these production cars built by Bentley Motors, Birkin got Gallop to engineer a racing series of four remodelled "prototypes" plus a spare:

*No. 1: a track car for Brooklands, but with headlights and mudguards.

*No's 2, 3 and 4: Road registered (No. 2 – GY3904; No. 3 – GY3905).

*No.5: a fifth car, registered for the road, assembled from spare parts.

Death

Gallop was thrown from a skidding car in Leatherhead Surrey on 7 September 1960. He was taken to hospital but was found dead on arrival.References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gallop, Clive 1892 births Royal Flying Corps officers British World War I pilots British automotive engineers Bentley Boys 1960 deaths Grand Prix drivers British expatriates in Egypt 20th-century English sportsmen